Owen Maercks

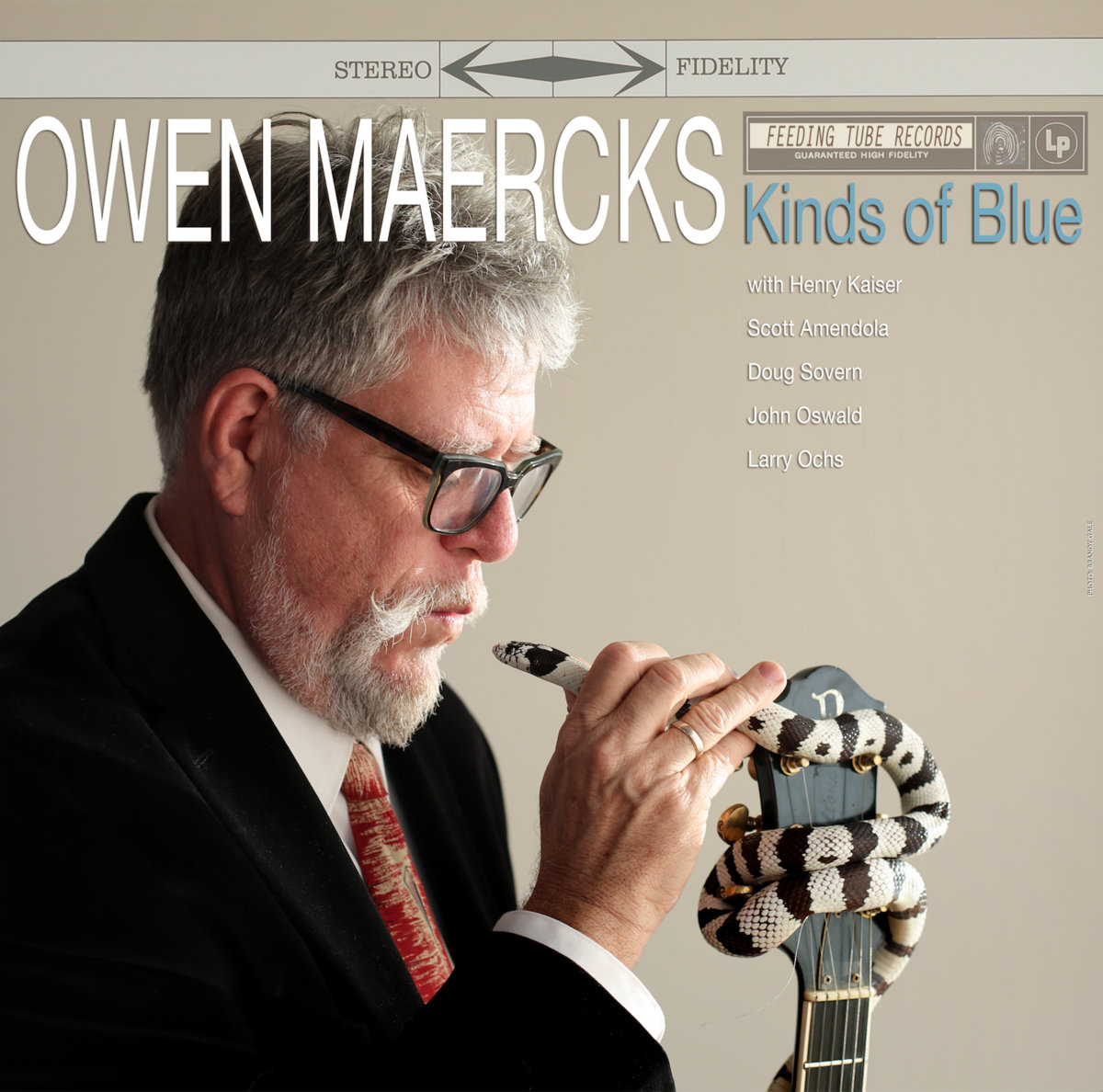

40 years after his first solo album, Owen Maercks made a second one called Kinds Of Blue, which refers as much to Miles Davis and blues as it does to free improvisation and psychedelia.

“I think a record collection is an amazingly accurate barometer by which to know somebody”

Why did you want to make a blues album with Kinds Of Blue? What would your definition of the blues be? Which blues musicians are you influenced by? John Lee Hooker and Captain Beefheart?

“Blues” is as slippery to define as “Jazz” or “Country.” It encompasses too much, historically and sonically, to have a definition be remotely useful. You know it when you hear it. My tastes in the music are similarly broad: favorites include Albert Collins, Big Boy Crudup, John Lee Hooker, Koko Taylor, Skip James, Canned Heat, T-Bone Walker, Gatemouth Brown, Howlin’ Wolf, and on and on. But I also include Ornette Coleman, Lou Reed, Ali Farka Touré, Captain Beefheart, and more in my list of Blues players. So how do you run a definition around that? You don’t.

Why did you want to cover Thelonious Monk’s “Blue Monk”?

Monk is one of the few jazzmen who, due to his strength as a melodist, could write a Blues that sounded like a Blues. I have been playing this song for years. His music has been covered ad nauseum, but almost always badly. Well-trained players tend to straighten out his idiosyncrasies in rhythm and harmony and ruin his sense of mischievous fun. I have zero jazz training, and so my approach is completely untechnical, but I did aim to return Monk’s *spirit* to the song. I hope that, from the great beyond, he is laughing at and with my version.

How did you get involved with Henry Kaiser?

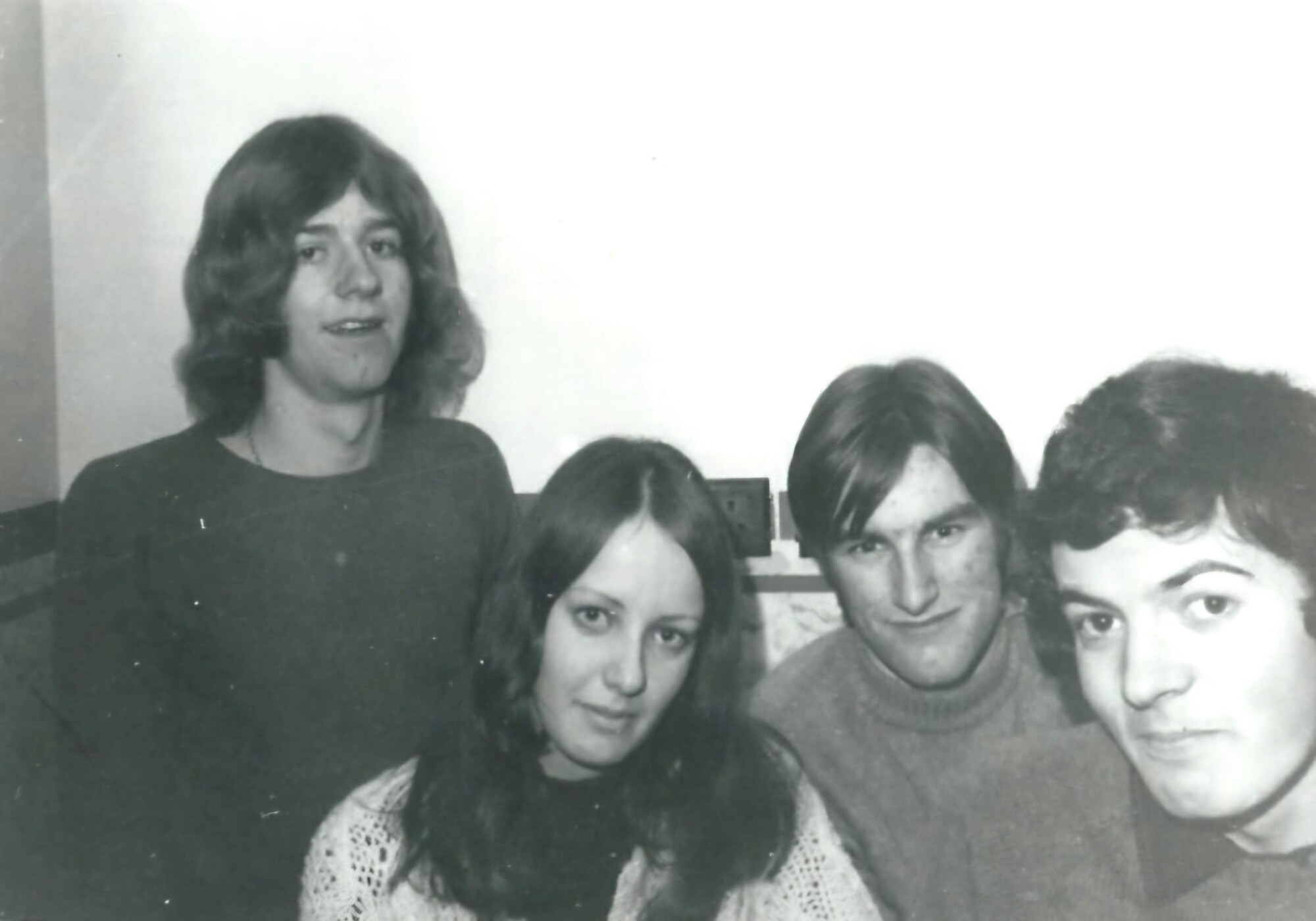

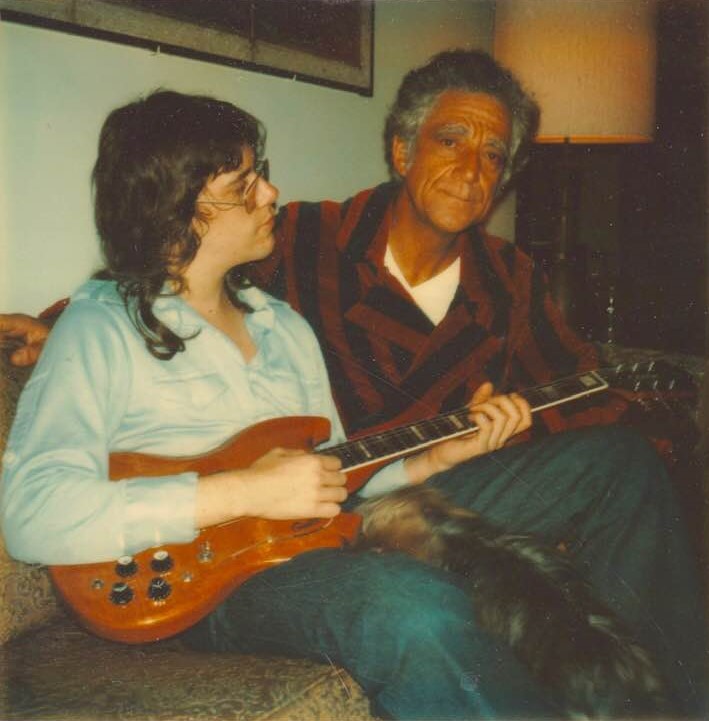

Henry and I met after he posted a “musicians wanted ad” on the Harvard campus that a friend noticed and passed on to me. One of the first questions Henry and I asked each other when we met in the mid-1970s was “Albert or BB?”

We both had a long history of loving Blues music, and it was one of the first things we bonded over. In our decades of friendship, we had played Blues together many times, but our tastes were so wide ranging, and broadened so much under each others’ influence, that it was a minor component of our repertoire. But we had talked about how much fun it would be to do an album of Blues material. A year ago, Henry thought it was time, and called me up and asked me to do it. I agreed.

Why is this only your second solo album? Why is there a 40 year gab between your first and your second solo album? You didn’t work for 40 years on this music, did you?

After my first solo record was recorded, I moved to the Bay Area to try my hand at playing music professionally. I bounced around through a number of projects and bands from 1978 to 1982, but never found the right situation/band, and by the early 80s, I felt musically lost and a bit defeated. At the same time, I had been working days (as all musicians must) at one of my other passions: herpetoculture (the keeping and breeding of exotic reptiles). I had a chance to buy the shop at which I was employed, and decided to put down my guitar, pick up my kingsnake, and pursue reptiles as a career.

Henry and I have remained fast friends through all of it, and five years ago Feeding Tube contacted me about releasing my “lost” album Teenage Sex Therapist.” It was a minor hit, and the label (and my friends) wanted more. Thus, Kinds of Blue. If it is successful, I’ll do another one in 40 years!

“Each track represents a different aspect of the Blues”

Why do you refer, in the cover art and in the title, to the 1959′ Miles Davis album?

The album is called Kinds of Blue because it reflects my very broad interests in the music. Each track represents a different aspect of the Blues, although, overriding throughout, is Henry’s and my deep interest in free improv and psychedelia, so if that is within the listeners’ taste frame, there will be much to like in it. Once we had the concept, doing a little visual nod to Miles seemed both fun and apropos.

How would you compare Teenage Sex Therapist to Kinds Of Blue?

Of course the binding element of the two records is the combined perspective and outlook of Henry and myself. I think our personalities show through in the music in very consistent ways.

There are two major ways in which the records are different. First, Henry and I have grown immensely over forty years. His playing on TST is testing things out and trying ideas. He now has a sound that is distinctly his own and unique. For my part, on TST, I was a vocalist, but clearly not a singer. I believe I have become a passable singer whereas I would struggle (and often fail) to find a melody back then.

More importantly, the genesis of each record came from entirely different sources. Back then, we were trying to learn production and attempting to land a record deal. Thus, we were trying to second guess what might be true to ourselves yet also be marketable. To that end, we were focused more on a rock and roll sound, with source points being Roxy Music and the Velvet Underground. This was genuinely music I loved, but I also thought the sound might bear commercial fruit. It did not, at least not at that time.

The new record comes from a place of pure love and inspiration, unfettered by career aspirations. To that end, we turned toward other loves of ours: Beefheart and the blues. This was all music we loved, then and now. We just chose a different focus here.

Were you aware of the cult reputation Teenage Sex Therapist got over the years?

To be honest, I hadn’t even thought about it for years before Byron Coley contacted me.

If you listen to Teenage Sex Therapist now yourself, what do you hear, what do you think, what do you feel?

I put it on the turntable when Feeding Tube expressed interest in it, and was genuinely surprised. I thought it was a bit better than I had remembered, and stuff I had disliked on it seemed OK.

Was your debut album originally self-titled and did it in later versions got Teenage Sex Therapist title, or am I wrong here?

Teenage Sex Therapist was the working title, though we opted to leave it off the promo copy as we thought it might impede getting it sold.

I have always loved exploitation and B-movies of any genre: sci-fi, nudies, blaxploitation, teen violence, etc. One day it occurred to me that Teenage Sex Therapist was a hilarious title/conceit for an exploitation movie, and this record seemed like a great place to put it.

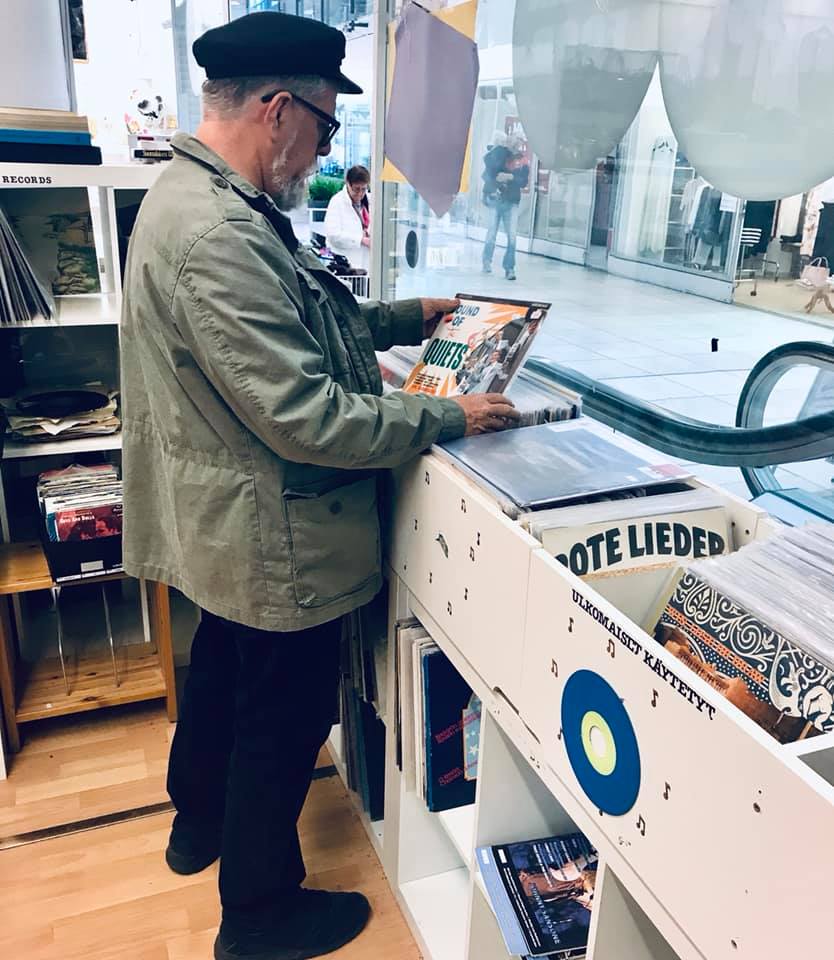

It’s often that people know It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine, because they are record collectors.

When I was 13 (1967) I was listening to Top 40 radio. My older brother came over one day and gave me three records: The Velvet Underground and Nico, Spirit, and Are You Experienced. That day changed my life (and I thank him on the back cover of my new record). I have been a music collector for 52 years; I became a record collector in the early 80s when I discovered record shows. The difference: music collecting is purely about the contents of the record. Record collecting focuses on issues, pressings, condition, value, etc. Before the record shows, I was not aware of the “Torso” VU as being special, and was pleasantly surprised as that was the one I had. Complete banana? Didn’t know it mattered. I still consider myself a music collector, but now informed by record collecting. For instance, I have never had a butcher cover. Don’t much care about the music, so the specialness of the cover is lost on me.

“The joy was in the hunt.”

My collection is a living breathing thing. I’m at about 15,000 LPs. Assembling it has been one of the great joys of my life, brought together bit by bit, piece by piece. I have tapered off lately, as I am almost 65; at some point, you become well past the ability to enjoy the records individually. Time is my enemy. But in my heyday, I was bringing home armfuls of records every week. Thrifting was a way of life. I also like small boutique record stores, and I think I was early on to the idea that antique stores overprice common records but completely undervalue rare treasures. The joy was in the hunt.

Whenever I go into someone’s home, within the constraints of good manners, I head as quickly as possible for the record collection. I think a record collection is an amazingly accurate barometer by which to know somebody. My collection is a virtual Rorschach of my inner mind and soul, subject to personal interpretation, but rife with meaning. It is me. It is the best Owen collection in the world, though it may completely suck to someone else.

I’m 43, so I grew up with radio and pop music magazines, with the hit parade: Michael Jackson, George Michael, and 70s artists who still made hits in the 80s; Queen and Elton John. But what got you into music?

I had the distinct advantage of coming of age musically in 1967, smack dab in the middle of the Golden Age of Pop Exploration. It was an amazing time, and my brain was exploding with new ideas and sounds on an almost daily basis. Simultaneously (and in this way I was different from most other kids) I was exploring back (in time, to previous decades) and out (to other styles and genres). By 1983 (not coincidentally the age of MTV), I felt that the pop mainstream was moribund and pathetic. I stopped following new music (with few exceptions) and started ever more fervently exploring backwards, where I soon learned that I knew so much less than I thought I did.

Why did you choose guitar as your instrument?

In 1967, didn’t everybody? My high school band had as many as four guitar players.

I’m not really a Bruce Springsteen fan, but when he was asked why he wrote an autobiography, he said he wanted to answer two questions for himself: “who am I?” and “what do I do?”. If I would ask you these same two questions, what would you answer?

Still learning about who I am (I don’t think even the Buddha can know that completely) and what I do? I breathe, I stand, I make noise, I love.

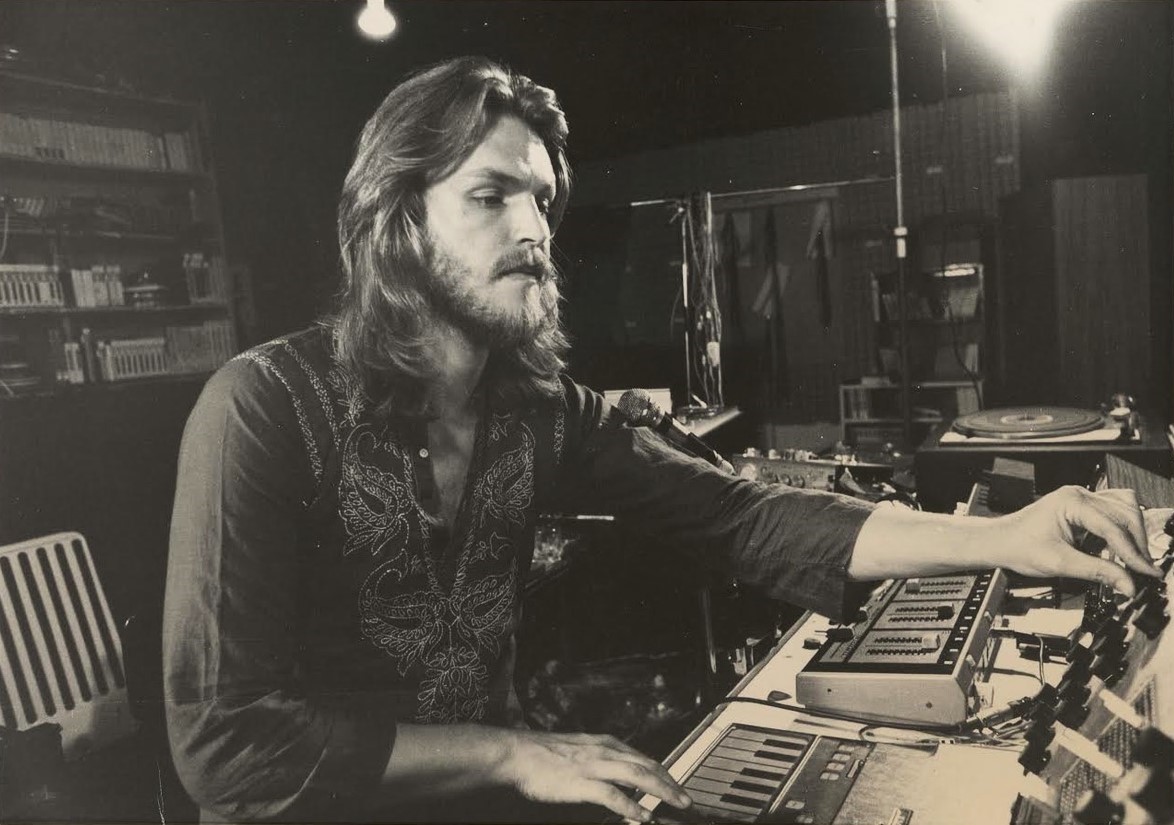

You used to have your own radio show?

Music Director for WCUW Worcester Ma. 1972-78.

Do you play live, or is it mainly about the record?

We are talking about doing a release party for the new record. I haven’t played live with a band since the early 80s. A bit nervous about it.

“I have always preferred things that seem to make sense rather than things that make sense.” Could you explain this quote?

The last line of John Lennon’s “Remember” is “Remember the 5th of November.” My birthday is the fifth of November. When I first heard that song, for just a split second, just a mere moment, I THOUGHT HE WAS TALKING TO ME! When someone writes lines that are very specific, they can resonate with, granted, fewer people, but in a way so indelible as to be, to those people, unforgettable. Similarly (and electric Dylan is a perfect example) when a lyricist writes something that has internal significance but is not laid out simply or by the strictures of common logic, the lines can resonate in a way more personally and strongly than your run of the mill commercial lyrics, designed to touch the maximum number of people, if only a little bit.

When lyrics are not didactic, but more nebulous, you allow the listener to interact with them in a personal way that straightforward lyrics do not allow. That brings the listener into them. Where there is no precise meaning, the listener can ascribe meaning. Clues are more fun than statements.

A John Cage quote: “I’ve never heard a bad sound, but man, did I hear a lot of bad music”. What do you make of that?

I like food. The best BBQ I ever ate was in a hole in the wall restaurant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. The front room was set up like a living room: a few couches, an old TV, and a table. As I ate, I watched a rat the size of a cat casually walk across the stove. I adore greasy spoon diners. I have also eaten in a few world class Michelin restaurants. Those experiences are all wonderful to me.

The food I hate is to be found in chain restaurants intent on producing cheap, bland, impersonal food designed to be palatable to the widest possible swath of Americans. Flavorless food in forgettable surroundings, designed to be boring and cheap and sold not by the quality of the product but by the temptation of the commercial.

That’s a lot of bad music.

Because this is for a magazine called It’s Psychedelic Baby: how would you define ‘psychedelic’?

I don’t. It’s like Art: I know it when I hear it. I think my new record is VERY psychedelic.

Hallucinogens are in my experience the ONLY group of drugs that can make you a better person, give you a deeper understanding, literally teach you things. The music of my youth was deeply informed by hallucinogens and better for it. My response to anyone who says “drugs are bad” is to ask them how they think popular music would sound without them. That is a horrifying thought.

But I will also say this: there is a point in cost/benefit analysis where they become less and less useful. It’s like professional students; if you are still in college after 20 years, something is very very wrong. Take them, learn some lessons, move on. Once you know, you know. You don’t need a refresher course.

I notice myself that, no matter how deep I dig into noise or avant-garde, at some point, I always return to ‘a good tune’, a song, a man and a guitar. Does that sound familiar to you?

As a listener, I couldn’t disagree more. I like to mix it up; no record I put on the turntable will be a predictor for the next one. That keeps it fresh.

As a musician, I have always tried to bring the techniques of the avant-garde to the song format. That unites Teenage Sex Therapist and Kinds of Blue. That is what makes me happiest creatively.

– Joeri Bruyninckx