Blake Hargreaves

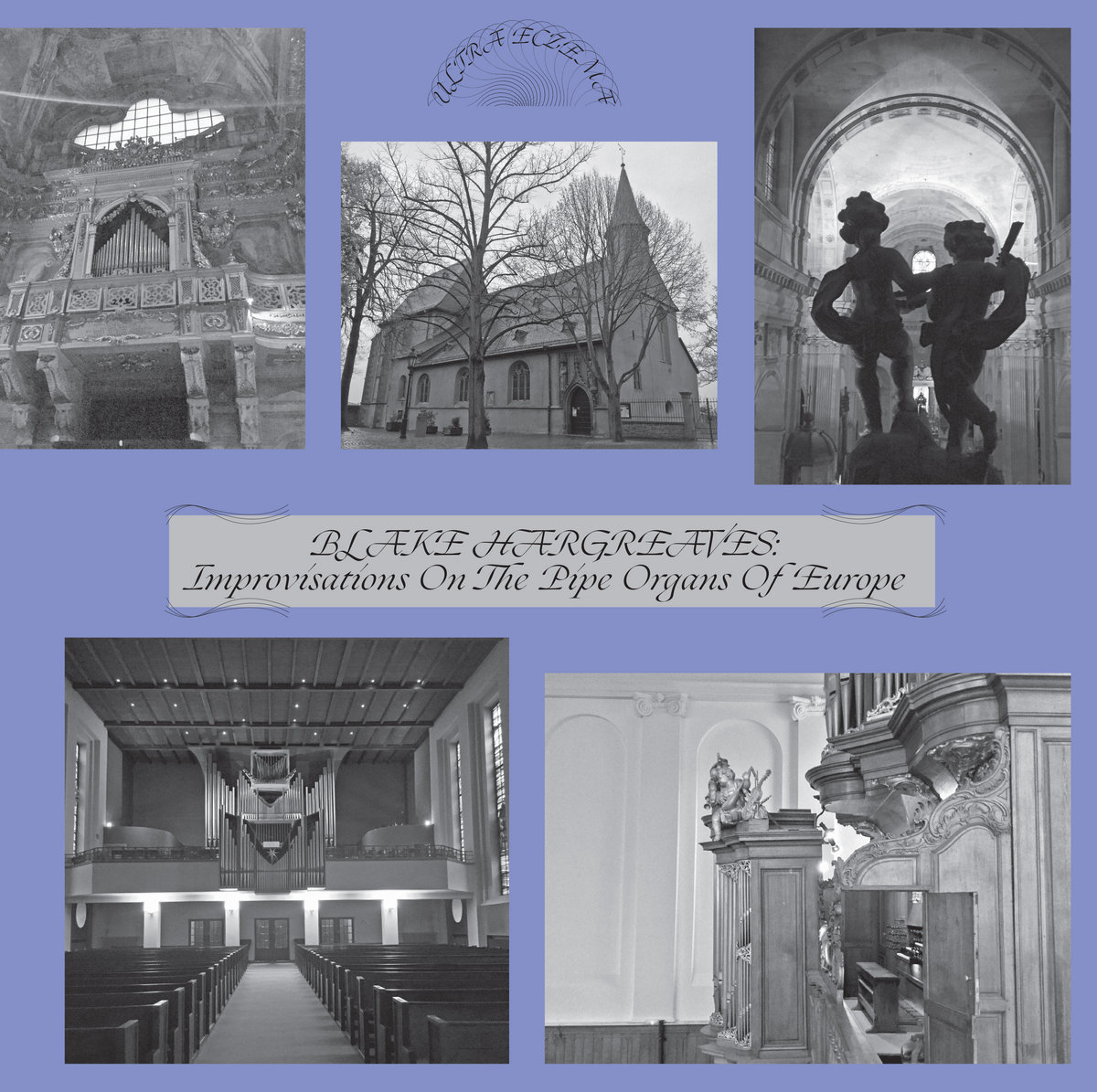

Canadian musician and visual artist Blake Hargreaves made an album with a title which tells you exactly what you will hear; Improvisations on the Pipe Organs of Europe.

“Exploring and describing the moment and the space”

How did you get into playing the church organ? Can you remember when you heard a church organ and thought: I want to play it myself?

Blake Hargreaves: When I was 11 I discovered by accident that some of my friends sang in a church choir. I was into classical music, but these guys seemed too cool for this kind of thing; they were all trying to turn me on to Sir Psycho Sexy and My Nuts at the time. Then I discovered that they actually got paid to be in the choir, something like seven dollars every two weeks. That was a lot of quarters for Altered Beast and Operation W.O.L.F at the corner store. I was in.

After about a year and a half my voice broke, and by that time it’d become very obvious to me that the big power in the ensemble was the organ. The church had a pretty large one in english symphonic style with two 32-foot stops (they go down to 16Hz). Some tuners described it as horribly over-built, way too much organ stuffed into a small space. It would distort and compress acoustically which is amazing to hear, and it had enough wind power to never sag (until they added the horizontal trumpets years later). There were stories about how it would cipher and break during weddings and it sounded awesome to me.

I became the page-turner for the choir director when he was playing. He hardly needed one, I once flipped one of those big long Bach books right on to his hands during a big postlude, and he didn’t even flinch, just played on looking at me with this single raised pointy black eyebrow, deep in a fugue with the book covering his hands, while I stood there, blinking. I was watching a working musician cut it for real, up close, and it blew my mind. Helping him do his job every week changed my life. Reading along in the score as the music played was a sort of composer’s contact high. There was no earth-moving moment when I decided I wanted to play, I just found myself doing it more and more. I started lessons, and made friends with the sexton (janitor) so I could practice at night. I spooked him with late-night rumblings on those 32’s in the dark. This was like having a slammin PA I could rock out on, in a 500-capacity venue, when I was 13.

Did you get lessons? Did you get an education into playing a piano, organ or church organ?

I started on piano at around 7 so I had a good start for getting the organ thing going. Basically as soon as I started, I was breaking out my own little jams at those late night practices, and my teacher heard some of it and suggested I play it Sunday morning while people took communion. I hadn’t nailed much down, it was mildly prepared improvising. It went fine and I started doing it fairly often, so eventually it was straight improv. Which is incredible when I think of it now: I was playing improvised music live, with less and less prep, in front of circa 200 people, once a week, when I was 13. At the moment in the week when those people would line up and pretend to eat flesh and drink blood or whatever. I think creating music to accompany a metaphorical millennial necro-cannibalistic ritual may have actually left me over-prepared for my 20s in the noise scene.

Is what you play on the church organ improvisation, or do you play compositions?

When I came back to playing organ in my mid-20s I was only doing improv, until I did a gig with a friend, and afterwards she was lamenting about how hard she’d worked for months learning her pieces, and meanwhile I just went up there and bullshitted. This rant of hers had the effect of motivating me to learn some repertoire. It took me a whole year to learn a six-minute piece, practicing five days a week for a couple of hours each day. After that it got a little easier. I’m only willing to learn stuff that impresses me, and that tends to be above my ability level. I’ve got a small handful of pieces I can play now.

Can I say you come from a noise background, and is the church organ a ‘noise instrument’?

Growing up we had a record store in Ottawa called Organized Sound, and that tipped me off to the textbook post-modern definition of music, which opens it up to noise. But before thinking much about it I was more into an OED ‘unwanted sound’ definition of noise, and what I saw and liked in the noise scene was people who were embracing pretty much anything marginalized, whether it was field recordings, harsh sounds on any instrument or extended technique, mutant pop/corporate-synth crap from the 80s, obscure world folk, anything badly recorded, etc. So to me ‘noise’ kind of means anything unusual, overlooked, but also potentially good. And years of chasing that stuff shaped me in this way where creatively I’m often drawn to things that don’t fit into my current musical world. Recently that’s been the pipe organ, and with the Ultra Eczema record, it’s meant music that’s pretty much straight up classical sounding.

The definition of noise as ‘unwanted sound’ also fits into spiritual themes. When people in the noise scene are all about repping shit you would never normally hear, it’s like making infinite space for the parts of collective humanity which are neglected, ignored, laughed at, or considered bad, failed, unwanted, or useless. Total cornerstone of meditation practice.

Editing improvised jams I’ve recorded is spiritually similar, as most of the hour is usually not that interesting, and it takes a couple of listens to find the tunes within. On rare occasions I walk away knowing I’ve got something, but with the best ones I usually feel like nothing happened, until a couple of listens later when I discover some gold in there. That same attention and acceptance is required.

The church organ is: the organ in a church. It’s the instrument and its environment. How do these two thing relate to each other, for you?

Obviously the acoustic space is a crucial consideration when building an embedded instrument, and playing any instrument. The first place I go when I start improvising is trying to articulate the space with sound, to warm up my ears.

As far as the religious aspect is concerned, a few years ago I was remembering one of those harsh noise performances from back in ’04 or so, with high volumes and walls of sound and a shirtless dude emoting in front of a possibly mesmerized crowd, and it just hit me how much the experience, for both performer and audience, reminds me of people in church looking to transcend. Taking drugs, making big, far-out sounds, the obsession with morbid imagery, the trippy clothes, everything.

My organ teacher in Hungary János said that the point is to elevate people with the improvisation. Another time he said it was about exploring and describing the moment and the space. These are concepts straight from meditation practice. Some of the jams I’ve recorded feel like they’re trying to be musical maps, or comforting soundtracks, for people taking that journey.

Occasionally when I play, I’ll stare at a stained glass picture of Jesus, and it feels right and comforting in this weird way (I am not a believer). Some ancient, weird familiar cultural shit that’s sort of appropriate somehow. The olden times. People in robes in the desert doing stuff. Iron age rustic living, interdependence with animals, simple agriculture, or whatever. No robots, no guns, no dinosaurs with lasers.

Religions can bring up so many gory feelings. The most positive reflection I can take from my making music in church is about bringing together things that don’t normally relate; “not fitting in” and “unwanted sound” come to mind. Working in a church seems like a very nonconformist way for me to make music, or at least it did when I restarted in ’06. It pleases me to see that it’s not so unusual anymore, people bringing new contemporary energy to the pipe organ. But being in churches all the time is weird, no question.

Are you ‘forced’ into playing slow? Do you automatically get into the drone thing, because of the nature of the instrument? Do you see your playing in the minimalist tradition? Or is what you do maximalistic?

I play slow primarily because I’m making it up as I go, playing with both hands and often feet, and combining up to 70+ different tone colours. Normally I just put my hands on the keys and play, but if I hear a chord in my head and I want to hit it, I have to use my brain to translate it into notes and that takes time.

Responding to the acoustic is another factor that can decelerate things. I like a really wet acoustic, it’s rich in overtones, distortions, it’s nice and forgiving, too. But it forces me to play slowly, with lots of breath. If the music is really harmonically rich, but has a prosaic melodic narrative, which a lot of my music does, in a really reverberant space it can be sort of like Assisted Living Dracula.

Is your playing influenced by Charlemagne Palestine and Hermann Nitsch?

You’ll hear a distinct Keni Burke influence on my signature track “Meditation at Kathedrale basiliek Sint Bavo 1, Haarlem”. This tune is my Dark Star, I try it on every organ I visit. With this kind of instrument that’s been around for so long, I seem to only be influenced by people who are already dead, or by my friends. I would like to mostly be influenced by people I know. I’m grateful for these two composers you mention because they’ve so effectively promoted new approaches to the instrument.

Do you feel related to church organ players like Kali Malone or Sarah Davachi?

I would describe these people as composers, not church organ players, and in that sense yes, I feel very much related.

You played and recorded at different churches, on different organ for this album. Why?

Two organs can be as different from each other as a cello and a Jackson Dinky, one of those little heavy metal shredder guitars. I want to get to know what’s out there, so I can learn how to make music on any organ. It helps keep me feeling fresh creatively, it keeps me listening at the right level. As I began doing it I realized that the music I make on each organ is a collaboration, and I started caring about the instruments a lot, and I’m convinced that sharing music made on them could help preserve them. Not everything can be preserved, and that’s ok, but these instruments and their resonant spaces are total wonders, and recordings of new music made on them, for them, should help them survive. I’ve recorded about 80 so far.

Why do you play only European churches for this album?

My project to record different organs started in Europe in 2016–2017 and this first record was drawn from that. In 2018 I recorded organs in Canada and a few more in Hungary and Belgium. This year I was in South America recording a bunch more. But Europe is the heart of organ making.

How does your church organ music fit into your other artistic activities? Which role do they play within your artistic output?

Lately it relates strongly to Cousins of Reggae (Olde English Spelling Bee, Our Mouth), our current approach is recording-based total free improv songwriting. In 2015, after working on the same set of songs for about five years, we showed up at jam and decided we would not play a single note we’ve ever played before and just record total free improv. Since then we rent a room every few months and record for two hours with the most basic gear and the same rule. In 2016 I started this intense study of pipe organ improvisation in Budapest, and realized I wanted to take the same approach. Sit down and play, no working on stuff, just put out. I don’t always follow this rule but it’s better when I do.

Working with Dreamcatcher (American Tapes, Ecstatic Peace!) and Thames (AA Records, American Tapes) in the past, I played mixer feedback, and a hotwired mixer could be considered a sort of voltage organ. Like a pipe organ, the energy used to make the sound is kept under pressure and released in a controlled way. The different channels are like manuals, and an octave pedal is like a coupler, etc.

Some of my painting is blitzing out with brocade motifs which are vaguely old and classic looking and ethnically ambiguous, and I combine those with geometric and organic elements, and the organ stuff sounds like that at times. I feel like in everything I do I’m combining old with new, narrative with organic chaos, in a bit of a mess, which helps me read them together.

If music is about the instrument and the space, what’s the role of a recording? Is a record ‘archiving a moment’? A way of keeping something that otherwise would get lost?

Recording is crucial to me because it can capture an improvisation. I can just turn my brain off and channel utter shit for as long as it takes for something good to happen; recording allows me to recover gems later. A live context changes the social economics of this process substantially.

I record jams because it sparks joy, man. And I have a feeling there’s gotta be something pretty special about the listener having the same experience as I am; they’re hearing the music for the first time when they put on the record, and there I am, on the record, hearing it for the first time too, as I play it. I mean, I guess technically every single take of the same composed song is different, like how every performance of a play is supposed to feel like it’s the first time this drama has ever happened. But on most levels recorded free improv is a lot closer to the shared reality of discovery with the listener. The actual raw material of the composition, the plot, melody, harmony, and rhythm, where it’s going, what it does, is reacting to itself as it’s happening; it doesn’t know what’s coming next. It seems to me this is a great use of recording technology. You’re not hearing something rehearsed and crafted, you’re hearing something totally spontaneous.

It relates to the spiritual stuff, once again, in that when it’s not a “jam” (riffing on patterns or comfortable forms and structures) but true free imrprov or auto-composition, it’s a sort of spiritual event, speaking in an unknown language, and communicating something honest and new that’s not premeditated. Any new music I listen to, composed or not, feels like that when I get into it as a listener for the first time. I appreciate that experience so much, I try to have it not just as a listener but as a player, too.

– Joeri Bruyninckx

Blake Hargreaves Official Website