Interview with Yasuaki Shimizu (Mariah)

A legendary yet long lost crown jewel from the early 80s Japanese Electronic and Jazz Rock scene.

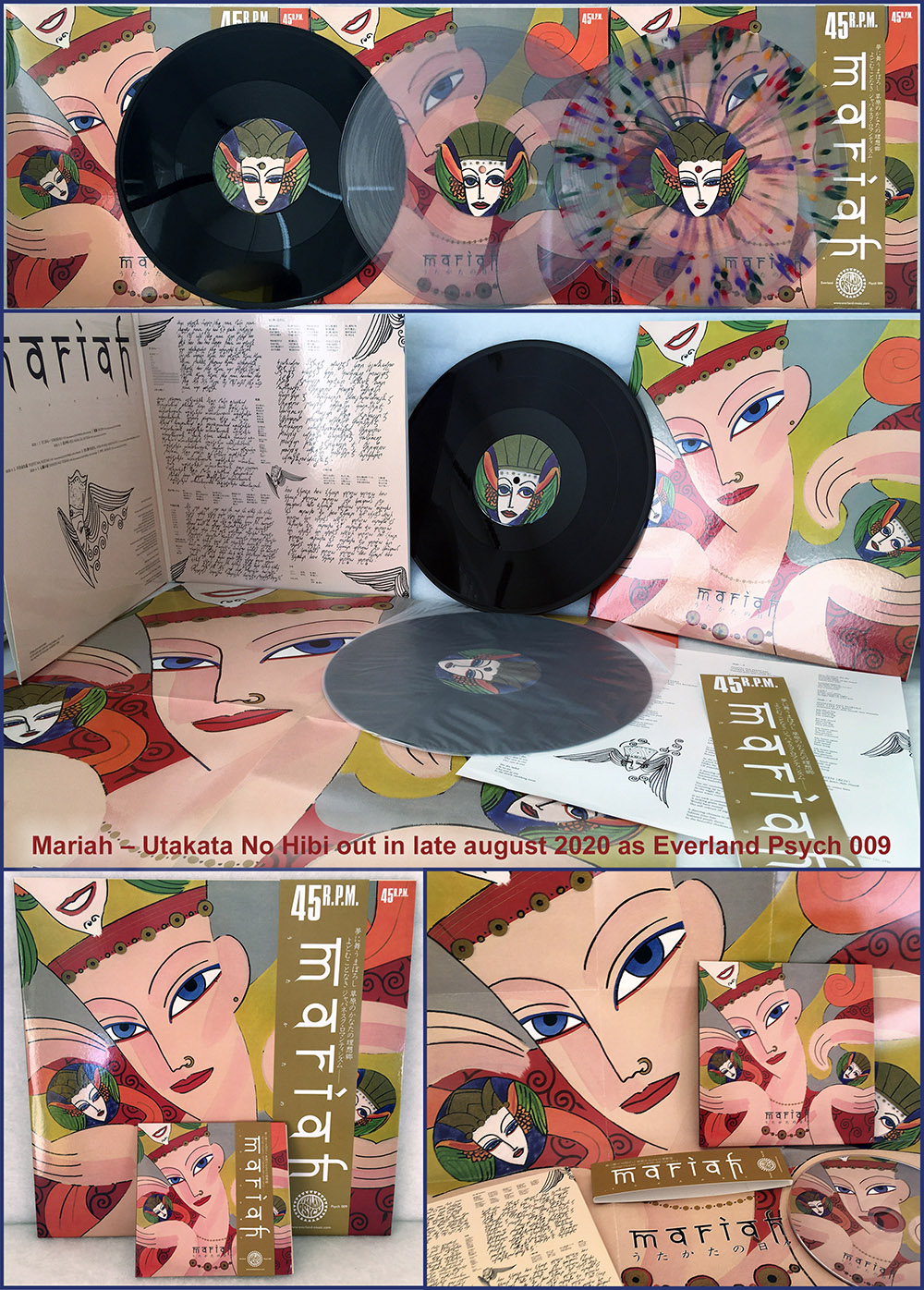

Mariah was a Japanese outfit in the field of art pop, way back in the very late 70s and early 80s with 5 albums up their score from 1980 to 1983. The album from 1979 entitled as “Mariah” was actually made before the band Mariah was formed, and was released as a solo album by Yasuaki Shimizu. The album at hand is the fifth and for the time being last album in this row, released as a double vinyl back in 1983. Original copies, that are at least in very good condition, are hard to find. The brand new reissue on Everland comes housed in a thick and artfully designed gatefold sleeve with OBI. The progressive, wacky art pop of this project was led by the popular Japanese composer and musician Yasuaki Shimizu, a relentlessly exploratory saxophonist who even dared to rework Johann Sebastian Bach’s cello suites for saxophone.

Utakata No Hibi reissue is available via Everland.

“Every day is all about sound.”

What was the original idea behind the formation of Mariah? Did you have another bandname, before you called the band Mariah?

Yasuaki Shimizu: Mariah came about when I met vocalist Jimmy Murakawa. There was no other band name before that. This was the first time I’d had a band.

What was the particular concept behind the group?

The dominant vibe of Mariah initially was progressive rock, I suppose. With an anti-establishment bent.

You were part of the jazz scene. Which were your major influences?

Prior to forming Mariah, I’d had the privilege of performing with various artists on the Japanese jazz scene. Which was all very valuable experience, and taught me a lot. Back in the ’70s Japan was packed with jazz clubs; just about every railway station seemed to have a couple nearby.

We assembled a small session group, and did the rounds of those clubs. During those years I was doing live gigs most days, occasionally three in a single day. Nothing but jazz, jazz and more jazz, day-in, day-out. Which had a huge influence on me musically, and psychologically, I think.

One thing I really appreciate learning back then was how to turn on a dime, so to speak, how to improvise when other musicians sprung something unexpected on me during a performance.

It’s impossible to describe your sound. You were truly an unique band combining various styles. How would you describe your own style?

At a personal level, the early 1980s were a turning point. The albums Utakata no Hibi and and Kakashi were recorded during those years. It would be fair to say, I think, that it was during the making of these albums that my hitherto fragmented state of mind, suddenly coalesced. It’s still a mystery to me exactly what changed there. All I know is that from then on, I found I could focus unreservedly on spinning the things bubbling up from inside me into sound. I therefore believe that these two albums formed the foundation of my style. Though I’ve launched plenty of other projects since then, my basic approach has remained unaltered.

Which are your other main projects and how do your projects and albums differ from each other in your own view?

Around the same time as Utakata no Hibi I released a few albums as part of the “Yasuaki Shimizu & Saxophonettes” project. The early Saxophonettes albums are L’Automne à Pékin (1983) and Stardust (1985). I approached this project differently to my solo efforts, or Mariah. Basically it was about placing greater emphasis on being static.

Stardust especially truly reflects this idea. The very slow numbers “Stardust” and “Humoresque” give the illusion of time standing still.

Also, I deliberately made this album as a 45rpm vinyl disc, which gives you the option of listening to it at 33rpm, for a taste of even greater stillness. I was always looking for opportunities to release albums under the “Saxophonettes” name.

In the late 1990s I turned to the triad of Bach, space, and tenor saxophone, did Bach’s Cello Suites 1–6 and released them under the Saxophonettes name. I recorded the six suites each in different locations, choosing places with great resonance that produced complex, distinctive sounds, including a former underground quarry, a mine tunnel, and a warehouse. When the strains of the tubular tenor sax echoed through such cavernous spaces, I felt as if I were physically dissolving into the space and hovering there, at one with the sound. An amazing sensation.

These albums consisted of saxophone solos by me, and overdubbed recordings, but in 2006 I welcomed four up-and-coming saxophonists into the fold, and launched the Saxophonettes project as a band, releasing Pentatonica in 2007. This album was also mainly about coaxing mutual resonance from space and saxophone, and for this new band I wrote some numbers using the pentatonic scale. I suspect that deep down my desire was to merge the album with Utakata no Hibi and Kakashi, both of which also used the pentatonic scale. We toured this lineup around Japan, and overseas to the likes of Moscow, Cuba and Hong Kong. I intend the Saxophonettes to be an ongoing thing.

In 2018 I did a European tour, and this prompted me to start a project utilizing saxophone and electronic sound. I asked Ray Kunimoto, who does sound installations and so on, to come on board, and planned a performance combining his Max Msp programming, and my Reaktor effects, to get some changing sound imagery for the saxophone in the space, and special acoustic effects. The program assembled a few tracks from Utakata no Hibi and Kakashi, “Hoho Jugatsu” from Pentatonica, plus new compositions. We decided on the overall progression, but rather than constructing each number, wove it from my improvised performance. Meaning that the performance had a different feel at each venue. I endeavored to draw on the acoustic differences at each venue, and the different circumstances on each day, and my different moods. The project has received favorable reviews, and I hope to continue it.

Another area I’ve poured considerable energy into is composing music for film and video. I’ve always been a huge movie fan, to the extent that whenever a new film came out, I’d skip school to catch it. For me, movies are like dreams. Dreams in which unreality becomes my physical reality through the camera lens… That feeling of intoxication continues right to the end of the movie.

In 1985 while living in Paris, I was fortunate to be commissioned for the soundtrack for Juliet Berto’s Havre (1986). I beavered away diligently on the score using an early computer I had brought to Paris, and I can still remember the job of dubbing the completed sound onto the visuals. Those chemical changes in sound and images, suffusing the silver screen, ensured that from then on, whenever the opportunity arose to be involved in a film project, I took it.

Which also means I was working concurrently on a number of the projects I’ve mentioned here. But in my mind each is closely connected to the others, the boundaries between them gradated, or rather blended, I suppose.

“Recording that album was a little like assembling a puzzle”

What are some of your strongest memories from recording Utakata no Hibi?

Ah… that takes me back. Utakata no Hibi: I can still feel it all like it was last week. Scenes from that period come bubbling up so readily. Recording that album was a little like assembling a puzzle; do one thing this way, another that. I’ve many precious memories of the time spent then with the Mariah members, but one of my most vivid recollections is of Seta and Julie in the studio working with us. Seta wrote verse in Armenian, and Julie sang it, in that darkened vocals booth. This was on “Shisen,” “Fujiyu Na Nezumi,” “Shinzo no Tobira,” and “Shonen.” The pair of them would lark about like little kids, then suddenly launch into intense philosophical debates, before falling silent. I suspect adding their sensibilities to the mix gave Utakata no Hibi a much broader worldview in many ways.

“I was interested in the actual ‘sounds’ that arose, the sounds that arose out of silence.”

Where did you record the album? What kind of equipment did you use? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

Recording was at the Nippon Columbia studios. I don’t remember exactly how long we spent making Utakata no Hibi, but I know it was time-consuming. We spent most of the day at the studio, even overnighting several times. It would be no exaggeration to say we basically lived at the studio. Back then, my style when it came to making music was to go into the recording studio with virtually nothing prepared, and put it all together from the ground up. I’d gather in the studio whatever sound sources and instruments had come to mind, and produce sounds according to my mood on the day. And if I found any specific tone or texture I liked, I would record it without too much thought and position it somewhere, then when editing the tape, loop those sounds perhaps, or use audio gear to engineer it into something with a distinctive acoustic quality. I also made generous use of synthesizers around this time. The synthesizers that appeared in the ’70s and ’80s were revolutionary. On Utakata no Hibi I mainly used a Prophet 5, and also an early sampler, an Emulator.

As well as immersing myself in the music, I was interested in the actual “sounds” that arose, the sounds that arose out of silence. The different harmonics of each, entwining. To me the acoustic images materializing from the speakers in the console room resembled a miniature garden, and I was fascinated by the dance of those sounds unfolding in the space of that garden.

Are you excited about the upcoming reissue? (the remastered sound, the gatefold sleeve, the poster)

I’m thrilled about the reissue. I consider the record cover here an expressive element of Utakata no Hibi, so am very happy to launch the album with its original jacket. The remastered sound is also excellent.

At the time when the album was originally released, it did not gain big attention in the Japanese public, but now many years later a wide audience has discovered the album’s brilliance and uniqueness. Can you imagine why the time for your great album came only later?

I moved to Paris after finishing this album, in 1985. I presented Utakata no Hibi and Kakashi to various people in the industry at the time, but there was little response. Those albums are however still re-released, albeit only in small pressings. I must admit that I heaved a happy sigh on learning that in recent years they’ve been unearthed by quite a few vinyl diggers and given an airing in all sorts of places. Utakata no Hibi is me, so I feel first hand all that texture I adore, and I’m excited that many others are now coming to love that texture too.

What currently occupies your life?

Sound, sound, and more sound. Every day is all about sound.

Thank you very much for taking your time for this unique interview. The last word is yours:

I spent my early years in a home surrounded by fields. Through all four seasons, sounds swirled all around. My favorite was that of insects in autumn. This is the time of year when bugs of different sorts start to chirp and call and sing at once. The sounds emitted by insects are incredibly diverse, with the pulses emitted by each individual combining to form complex polyrhythms. I imagined those insects were communicating with each other by sound, then extended that to imagine that maybe they were sending pulses out into space. I believe that even now it is this experience that drives my ambition to make music. The environment of daily life, and I, are as one. And at times those tiny sounds I find impossible to ignore – in fact that are so dear to me I cannot leave them alone – resonate in me physically. I plan to carry on living this way, as long as I can hear these sounds.

– Klemen Breznikar

Yasuaki Shimizu Official Website

Everland Music Group Official Website

Good interview, another vintage group to check out. Shimizu’s an articulate intellectual and has an interesting musical career.