“This isn’t a war, it’s a happening”: Con Bà Cu’s Peace Message from PSYCHEDELIC PSAIGON

Everybody knows the Vietnam War had a soundtrack. Call it collective memory or call it Hollywood, but the sounds and images are all too familiar.

The thwap-thwap of oscillating helicopter blades taking off from a firebase, interlaced with ‘Nowhere to Run’ by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas crackling from a nearby radio. The young, dust-caked faces peering from beneath their helmets in the trenches of Khe Sanh, ears ringing when the ear-splitting shriek of incoming rockets interrupts the minatory throb of the Animals’ ‘We Gotta Get Out of This Place.’ The booming crump when the B-52’s bombs find another target, gouging holes in tortured earth and human bodies alike as the pilot listens to Iron Butterfly’s ‘In A Gadda Da Vida’ through his headphones.

To quote one veteran, “it seemed as if our music- the rock ’n’ roll sounds that we brought with us on our records and albums and cassettes, in our fingers, on our lips, and in our heads- was colliding with the brutality of war and ricocheting off the Vietnamese landscape.”

After all, the American experience in Vietnam was one of excess, not solely in terms of disproportionate use of firepower. That the peak of the U.S involvement- between 1967 and 1971- coincided squarely with the era of flower power, acid and free love, ensured the incubation of a truly bizarre micro-zeitgeist.

Army barracks decked out with lava lamps and psychedelic posters illuminated by black lights. Attack helicopters painted with peace signs but bristling with lethal weapons. Soldiers festooned with machine gun bandoliers and love beads clutching their rifles grimly as, up ahead, yet another rural village is doused in napalm and disappears behind billowing flames. When flower power met firepower on the battlefields of Vietnam, the blissed-out Age of Aquarius played out to the discordant backdrop of chattering machine guns and an audience of the mangled, carpeted dead. Vietnam became ripe with oxymoron as the horrific banality of the war’s violence stuck like a chemical burn to the iconography of peace, love and counterculture.

When Mark Jury disembarked at the port of Da Nang, his first impression of the Vietnam danger zone was deceptive. As an armoured personnel carrier charged past an ice cream stand, the gorgeous blonde-haired woman in the front hatch flashed a carefree smile in his direction. Watching her hair trail like a ribbon in the wind behind her, Jury thought to himself, “this isn’t a war.”

“It’s a happening.”

Such a sentiment was far from unique amongst those who experienced Vietnam’s schizoid psychodrama in real time. In a nauseatingly absurd war full of absurd sights and absurd scenes, the surrealism of psychedelia was a lens through which to understand- or, conversely, to obscure- the unthinkable.

“There’s some good things going here, man,” one G.I explained in 1970, “but you got to know where it’s at.”

For a portion of South Vietnam’s urban youth, the distilled sights and sounds of American counterculture brought by young G.Is to Saigon’s streets represented a chance to escape, if only for a while, from the brother war being fought against the communist North. Where some saw American cultural imperialism, others saw an opportunity to replace the stench of death drifting from the jungles with those of patchouli and incense.

“It was neither communist nor capitalist,” Michael J. Kramer writes, “but rather a kind of tie-dyed, pot filled Electric Ladyland– as Jimi Hendrix called it- a psychedelic swirl of the existing order into something else.”

Just as the South Vietnamese armed forces are often overlooked in the Americentric narrative of the conflict, so too are the contributions of South Vietnamese musicians in forging the war’s distinctive soundscape. Few would recall the paranoiac atmosphere of wartime Saigon to be conducive to the carefree epicureanism that embodied swinging Sixties youthtopias such as San Francisco or London, but, nonetheless, a unique and effervescent music scene flourished there before being snuffed out upon the city’s fall in 1975. The combination of traditional Vietnamese musical motifs with the novel influence of American rock, pop and soul led to the creation of a new form of ‘Tan Nhac,’ or ‘modern music.’

Phan Linh, his sister, Loan and his brother, Van, were initially, drawn to performing music as a means of supporting their mother after their older brother, Lan, was conscripted into the South Vietnamese military. Lan and another older sister, Ly, tutored them in performing both Vietnamese traditional and Western forms of music, the latter of which was steadily growing in popularity with the gradually increasing American presence in South Vietnam. By 1961, the trio had cut their teeth performing on the streets of Saigon, and by 1963 had even featured on one of the city’s most widely listened to radio stations.

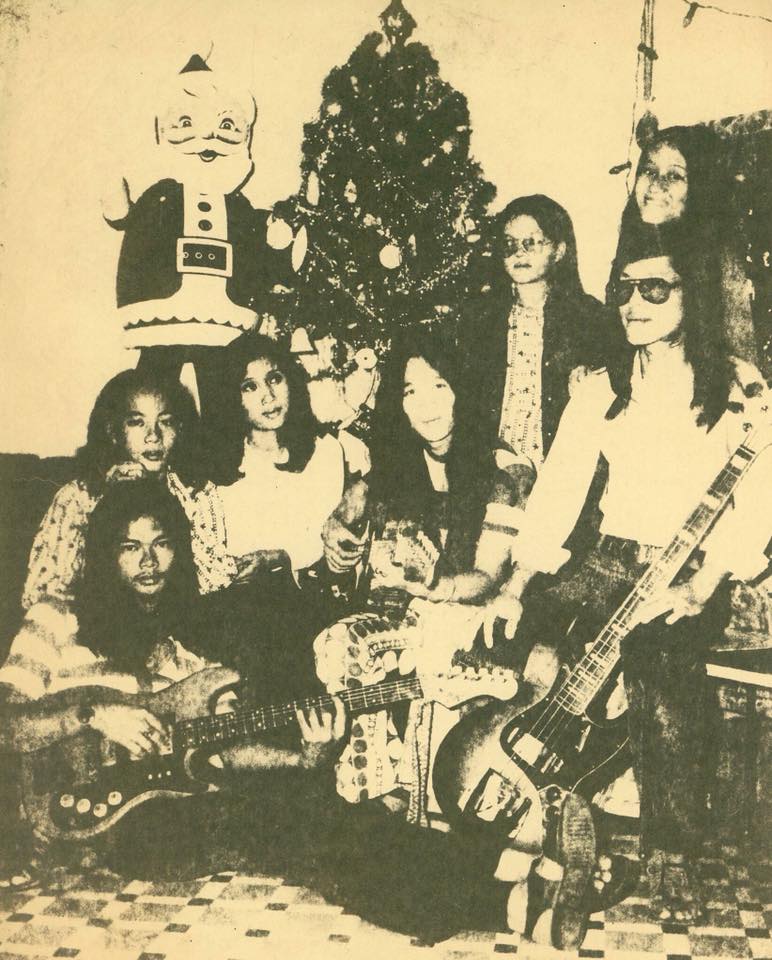

They comprised the embryonic core of “Con Bà Cu”, or “Mothers Children,” a moniker provided to them by their ever-supportive mother. More commonly referred to as the CBC Band (or, alternatively, the ‘CBC Group’), by the 1970 their reputation preceded them to the extent that Rolling Stone magazine proclaimed them to be the “best band in the Orient.”

In 1964, the CBC Group performed for the first time for what was to become a crucial component of their demographic and a key source from which to accrue new live material. At a firebase at Can Tho in the Mekong Delta, they endeared themselves to a contingent of American servicemen with a proficient, nimble-fingered cover of ‘Wipe Out’ by the Surfaris.

Not only could they make a living by performing American music for homesick troops; they could also vicariously experience a modicum of the youth-centric cultural revolution sweeping the world through the records and cassettes lent to them by G.Is who hoped to hear their favourite songs covered by the fledgling band.

By 1965 the war had escalated, and a steady flow of American troops arrived daily, bringing with them the newest records from “back in the world.” It was apparent that the apolitical instrumental rock that had defined the early Sixties- the Shadows, the Surfaris, the Ventures- were out, and the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Motown were emphatically In.

“I still remember the first 45s, the small discs, by the Beatles,” Linh recalled. “It flipped me out.”Just as contemporaneous and celebrated American garage bands such as the Shadows of Knight, the Seeds and the Standellsset about learning the songs they loved by ear, replicating the vibrations fizzling from their transistor radios to the best of their ability, so too did CBC.

“Whatever song I learn,” Linh further recalled, “I try to play exactly like the way that the original artist plays because I respect them so much.”

Circumventing the challenge posed by the English-Vietnamese language gap, lyrics were learnt phonetically in the early stages of the group’s career. Loan’s talent for vocal imitation was to prove just as crucial to the CBC sound as Linh’s guitar virtuosity; indeed, a number of Americans offered Loan the backhanded compliment that they could understand her only when she sang.

CBC were far from alone in consuming and recreating contemporary rock and soul in the mid-Sixties. To quote Mark Gergis, “this era saw the birth of a vibrant rock scene that included Saigon based groups such as the Enterprise, the Magic Stones, the Dreamers, the Soul and the Music Makers.” Other South Vietnamese ensembles, such as the Black Caps, Les Vampires and the Fanatiques, also revelled enthusiastically in Western popular music.

Towards the end of the decade, however, a new sound-indeed,a new culture- was draping Western popular consciousness with flashing flowers in every conceivable neon colour. It was the pink dawn of psychedelia’s golden age, and few vestiges of South Vietnamese music would remain untouched by its day-glo reach.

Psychedelia found its way to Vietnam not via Donovan’s Trans-Love Airways, but, rather, on the wings of those hulking silver birds that touched down daily on the great runway at Tan Son Nhut Airbase. Spilling out onto the hot tarmac, each new olive green draft cohort arriving “in country” brought with them the gospel of strange new bands with strange new names, all of which attained airplay on Armed Forces Radio via a show named- of course- ‘Sgt Pepper’s.’ The Doors, Big Brother and the Holding Company and the Grateful Dead (to name but a few) were reporting for duty.

For CBC- who, by now, were bolstered by the addition of another sister, Lien, and Linh’s wife Mary Louise, to the lineup- the advent of the psychedelic revolution was nothing short of revelatory. The blistering napalm guitar work of Jimi Hendrix was to prove a particularly strong influence for Linh who, by the late 1960s, had grown proficient at covering even his most complex arrangements. ‘Purple Haze’ (the title of which inspired a nickname for the U.S Army’s M18 smoke grenade) would grow to become something of a fixture within the group’s live repertoire. Even Hendrix’ distortion-laden deconstruction of the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ was tackled by CBC with aplomb, its’ anti-war sound collage of bursting bombs and glaring rockets all the more powerful when played from within the eye of the Vietnamese storm. To paraphrase Bob Dylan, such invocations were illustrative of the battle outside raging- the explosions they evoked were the very same blasts that were shaking the band’s windows and rattling their walls.

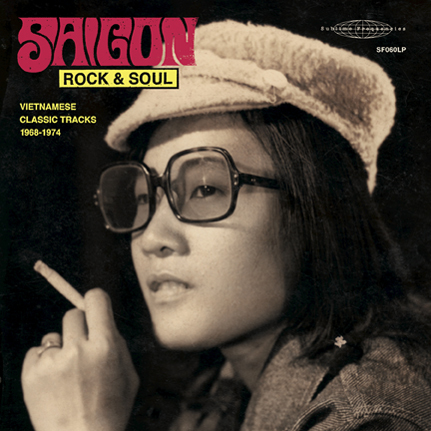

In 2010, the Sublime Frequencies record label issued ‘Saigon Rock and Soul: Vietnamese Classic Tracks 1968-1974,’ an album that collated 17 tracks showcasing South Vietnamese musicians’ short-lived appropriation of Western form. The LP strikingly highlights the parallels between the Saigon scene and the global counterculture, not to mention the unique traumas, paradoxes and desires of a generation coming to terms with the increasingly destructive war consuming their homeland.

CBC lead the charge and provide the first track, entitled ‘The Greatest Love.’ One of only two original studio tracks the band cut- the other, ‘Heart and Tears,’ features later on the album- ‘The Greatest Love’ was recorded for a 1972 Vietnamese comedy film by the name of ‘Ngoui Co Don.’ Opening with a well-executed, proto-trip-hop drum loop, CBC unleash their full potential over the course of just under four minutes of pounding, go-go dancing ecstasy. Of course, there is plenty of Hendrix to be heard in Linh’s firework display of grinding sandpaper guitar, but also a hint of Yardbirds when he launches into the patchwork liquid rave-ups that leap unexpectedly from the mix like pythons from the long grass. All the while, Loan’s soulful, sometimes throat-tearing vocals imbue the group with an earthen authenticity at times missing from CBC’s manufactured contemporaries.

Elsewhere, over the course of the disc, traditionalism and modernism clash both lyrically and sonically. Singing over a tight psychsploitation groove, Thành Mái laments a love affair with a musician brought to an untimely end by her arranged marriage to another man in ‘Long, Uneven Hair.’ Elsewhere, Hùng Cường & Mai LệHuy’n’s ‘Jealousy’ positively simmers with hip scornas, in a modish fusion of Vietnamese classical and French style yé-yé pop, the disparity in opportunities between men and women within conservative Vietnamese society are invoked. “The life of a man has hundreds of ways,” the singer intones with audible resentment towards her war-bound lover, “but the fate of a girl has only one.”

Predictably, the harsh reality of the war looms over much of the included material, rendering the typically upbeat nature of the recordings with a poignant, if occasionally eerie, dissonance.

For instance, Thai Thanh’s ‘Dawn,’ which, lyrically hones in on a couple’s final night together before the young man’s deployment, has a Carnaby Street-esquebossa nova flavour, featuring R&B flavoured saxophone and chipper accompanying vocals that offer no outward indication of the sickly dread that surely permeated such an episode in real life. Similarly, Elvis Phuong’s frenetic ‘Crazy Song’ could easily be mistaken for an outtake from the ‘Psych-Out’ soundtrack, but its lyricist’s concerns stray far from Haight Ashbury’s bum trips, choosing instead to focus upon the failed promises of the Vietcong to transfer wealth from the rich to the poor.

Later, Bang Chan’s melancholic ‘Fireballs’ is featured. Punctuated with chirping organ, pummelling fusillades of circular drumming and a gristly guitar riff that sounds like a bulging vein on an angry forehead, it makes pointed reference to the searingly bright illumination flares that shot nightly into the skies above the jungles.

Meanwhile, Minh Xuân & Phượng Hoàng’s ‘Black Sun’ is perhaps one of the best bad trip acid rock freakouts of its era. Sung over, in the words of James Allen, “some of the rawest, nastiest fuzz-guitar snarl you’re likely to hear anywhere this side of a Blue Cheer box set,” the vocal delivery is initially dispassionate, resigned even, as it builds incorrigibly to a frenzied climax. The lo-fi mastering of the recording works in the favour of ‘Black Sun’, providing it with a brittle texture not all too dissimilar to the Velvet Underground of the ‘White Light, White Heat’ era. As the lyrics make clear, this is a far cry from the psychedelia of Cheshire cats, mad hatters and holes in one’s head where the rain gets in. Rather, ‘Black Sun’ is scorched-earth disillusionment, toxic toad psychosis, and pairs of luminescent eyes peering orange and yellow from behind the canopy.

“The sun is so black, black like our life. Life is like a homeless dog at night. Don’t trust or believe, or else you’ll be crushed and part with your hopes and dreams. The black sun is still the king of the dark shadows, of memories. I want to forget, and wish away the sadness. The sun is black, black like the night. Why do I still see the sun as black as ink?”

Whilst U.S military personnel were still ostensibly the main audience for such material- most Vietnamese bands made a living selling cassettes of their recordings to G.Is, or performing to them within the confines of their barracks- Saigon’s youth began to take notice and a denizen hippie movement began to gain traction. At the Kim Kim Club and the Fillmore Far East (the latter taking its parodic name from San Francisco’s iconic bastion of psychedelia) off-duty U.S troops and Vietnamese civilians alike began to assimilate the aesthetics of the Haight Ashbury scene. Drug use was typically prohibited within such premises, but, in an easily exploitable loophole, little could prevent patrons from imbibing outside before they entered through the looking glass.

“Happiness is Acid Rock at Plantation Road” reads the drooping psychedelic font on page 3 of the October-November issue of the Grunt Free Press, an underground magazine of the Oracle/Avatar ilk self-published by serving U.S troops. In a photo collage bearing resemblance to the sleeve-art of the Beatles’ ‘Revolver’ or the Grateful Dead’s debut, the faces of the CBC band peer out from the page.

“On the stage there are five young Vietnamese musicians, none over 21, all unisexed with long hair,” the accompanying article reads. “Behind them is a bright orange and red peace symbol, psychedelic posters selected at random, showing the finger V for peace.”

“On the stage itself and in rows of stools in front of it,”the reporter continues, “are about 200 G.I’s in fatigues, Army and Air Force mainly, all between 18 and 25 and none over the rank of buck sergeant. There are also about 50 Vietnamese teenagers in the crowd. The volume is turned full-blast and the music bounces off the ceilings and walls, cool and hot music, right off the top of the charts and played with Woodstock intensity.”

“It’s a warm scene, as mellow as any found in Haight Ashbury, Greenwich Village, Santa Monica, Des Moines, London, Paris, Berlin, Tokyo, and anywhere else where under-30s groove together.”

“Their hair is long enough to bring harassment from Vietnamese M.Ps who keep threatening to cut it off,” the Grunt Free Press continues, “and U.S M.Ps who call them ‘dirty people.’ The musicians call the police ‘pigs.’ They chafe under the harassment, but they know that every G.I in the audience would go to bat for them if there were real trouble. On one occasion, when the M.Ps harassed the group, every grunt walked out of the place.”

Young American servicemen loved CBC for bringing a version of the stateside hippie movement they were missing out upon to the warzone. “You writing a story about this band? It better be good,” one soldier insisted to the Grunt Free Press journalist responsible for the Plantation Road article. “These guys made this tour worthwhile. They got it. They just got it- and I ain’t found it anywhere else.”

In this capacity, CBC served as a vital humanising factor in countering the orientalist racism that plagued the U.S military of the Vietnam era.

After all, the ability of the U.S military to carve firebase enclaves full of recognisable American affluence in the jungles of South Vietnam, Meredith Lair recounts, “served not as a moderating influence on excessive behaviour but rather as a legitimising signifier of U.S superiority… What emerged was a moral wonderland in which stateside checks on taboo behaviour simply did not exist.” There emerged a rift between the U.S and the South Vietnamese populace they were to all intents and purposes deployed to defend, given the contrast between the rabid consumerism of American society against that of the less materialistic South Vietnam. The war-torn, impoverished rural hamlets where much of the patrolling and fighting took place appeared particularly alien, and even the most thoroughly country-bred G.Is must have felt metropolitan when faced with the deprivation of such battle denuded villages.

The cultural gaps with regards to the Vietnamese social tenets of familial tradition, traditional courtship and anti-avarice might have been bridged had they not so often been forcefully crossed by bullish American troops.

Historian Bernd Greiner recognised within U.S forces a “common tendency only to recognise civilisation when it mirrors ones’ own world”, leading to a dehumanisation not only of their North Vietnamese/Vietcong enemies, but the Vietnamese people as a whole. He further theorised that “maintaining that the Vietnamese live in filth can seamlessly metamorphose into deciding that these people are filth and not worth the exertions demanded from the G.Is.”

This mentality is plainly visible in the account given by U.S Navy aviator and former prisoner of war Lieutenant George Coker, who was filmed telling a young American schoolgirl that the people of Vietnam were “very backwards and primitive and they make mess out of everything.” General William Westmorel and, commander of U.S forces between 1964 and 1968, was also filmed justifying the war’s high civilian death toll by arguing that “the Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as does a Westerner. Life is plentiful. Life is cheap in the Orient.” Even President Richard Nixon was dismissive of the Vietnamese, particularly when he concluded that if the Communists hypothetically slaughtered two million South Vietnamese civilians “nobody would have cared”, deriding them as “little brown people, so far away.”

Such contempt was far from reconcilable with the ‘hearts and minds’ approach to the guerrilla war in Vietnam, instead generating mutual distrust and outright American racism towards their South Vietnamese allies that enabled a counterproductive mentality that their lives were disposable. Testifying at the ‘Winter Soldier’ trials in 1971, U.S Marine helicopter pilot Rusty Sachs recounted his superior officer denying permission for a medical evacuation of wounded ARVN troops. “These are only ARVNs,” he quoted his commander as stating, “they aren’t Americans. These are gook Marines. We don’t need ’em. We’re not going to risk ourselves for them.” He further added that “it was a squadron policy, unwritten, not to launch for gooks if you could possibly avoid it.”

The commonalities between CBC and the American servicemen who came to witness them, therefore, were a unifying influence that challenged pre-existing racist notions of Vietnamese identity harboured within U.S ranks. “Most G.Is, before they hear us play,” Linh noted, “look at us as long-haired gooks… But after they hear us play, they don’t look at us as gooks anymore. They realise that we are people.”

The burgeoning Vietnamese counterculture did not go unnoticed by the governments of the warring parties, all of whom viewed it with scepticism and mistrust. The Southern Republic of Vietnam characterised it as ‘an abandonment of Vietnamese identity,’ whilst the Communist North saw a self-indulgent means of distraction- or perhaps even an outright psychological warfare campaign designed to “keep the youth aloof from the revolutionary path.” Even the U.S military- who, by the early 1970s had placed the CBC Band upon the approved entertainment list for American troops and offered them $325 dollars per gig- began to grow wary of Vietnam’s homegrown psychedelic bands, fearing a Vietcong plot to lure military personnel into a web of recreational drug use and anti-war rhetoric.

However, as Mark Gergisnotes, the true rallying impetus for would-be Vietnamese hippies lay with “a vision of peace from the heart of war, not a Pax Americana so much as a Pax Countercultural.”

It’s a key distinction, given the unique position of Vietnamese young adults who adhered to the hippie model. For a start, they were not blind to the atrocities committed by the same American troops who had introduced them to the counterculture in the first place. Nguyen Qui Duc, a teenager in Saigon in the early 1970s, aptly illustrates this paradox in his recollections of the period:

“The Western influence raised contradictory questions. American youth culture was very catching to me and my friends. We wore peace symbols and went to the flea market and bought T-shirts with the names of American universities on them. We grew our hair and listened to Jimi Hendrix and Neil Young and the Who.”

“At some point,” he adds, “my friends and I began to ask, how can a country that produced hippies and such cool people also fight a war and kill people and act cruelly? You would see American GMC trucks go by and soldiers reaching down to whack a girl riding a bicycle. They would yank at her hat and she would get thrown and she would die… But then you’d take an English class with an American soldier from Ohio who seemed just as nice as anyone, yet he was a soldier too.”

CBC’s lead singer, Phan Loan, added further weight to this consensus of confusion when she stated that “the United States must be the greatest paradox in the history of the world. It puts the best conceivable sounds in its music and the worst conceivable sounds in its weapons. Its children want peace but fight a war against an aggressor who has never really threatened the soil of the United States. A mixed-up country.”

That tradition played a more influential role in the philosophy of Vietnamese teenagers when compared to their American counterparts proved yet another factor altering the shape of Saigon’s psychedelic expression. In another Grunt Free Press article entitled ‘The Most Uptight Teenagers In The World,’ a performance by “three of the top groups in the country- the CBC, the Moonbeams and the New Flintstones,” is described:

“The beat is loud and rhythmic and the performers are wiggling and hamming under the flashing coloured lights. But the audience is dead. They sit there, maybe 100 of them, seated like they were watching a movie, and just dead, not moving a foot, a hand, or a head to match the beat. The contrast between the bands and the listeners is startling. Woodstock it ain’t. But every Sunday, it’s standing room only, so you know the kids dig the stuff. But why the inactivity?”

The rest of the article is composed of an interview between a soldier-cum-journalist and an unnamed Vietnamese student. The student’s answers provide an illuminating glimpse into the psyche of Saigon’s statuesque ravers.

GRUNT: Why don’t these teenagers move to the beat?

STUDENT: They’re numb, that’s why. Inside they want to move and express themselves and be individualists, but you can’t do it in Saigon today. They come here to escape the frustrations of knowing that all they have to look forward to is the draft and the war but they can’t escape it entirely. They can’t let themselves go.

GRUNT: Is there much free sex among students over here?

STUDENT: No, the family influence is so strong that sex is not really free. And there are strict university rules on sex…. The war has had something to do with a lowering of moral standards, but for the young students, sex is not easy to come by. Not only are our families strict, but they never teach us anything about sex.

It is of no surprise that the sexual revolution that coincided with the emergence of counterculture would take on unique cultural ambiguities within South Vietnam, with certain hippie attributes taking on unintentionally conservative functions. For instance, the unisex hippie uniform of casual shirts and long jeans (à la Janis Joplin and Grace Slick) favoured by the women of the CBC Band may have represented a rejection of traditional gender roles back in America, but for Loan, Lien and Mary Louise in Saigon it offered a reprieve from the skimpy, over sexualised costumes expected of a number of the female performers and escorts who scraped a living through entertaining American troops.

Loan, Lien and Mary Louise were seemingly spared from the rampant sexual violence that unfortunately befell many of their contemporaries. As one veteran explained, “if you get a room full of very horny, very frustrated, bored men, some from the roughest streets in the cities, and bring on these Filipino and Korean girls, in these sequins and in these bands that were playing imitation American rock, and get the heat going, what are you going to do with all of that energy?”

A number of young G.Is, exasperated by combat that in no way resembled the battles depicted in the war movies and Westerns that were so popular in the 1960s, felt emasculated by the realities of guerrilla warfare. 80% of the war’s firefights were instigated by the Vietcong/North Vietnamese forces, who stalked unseen through the thick vegetation and could disengage and vanish into the jungle seemingly at will. Mines, such as the greatly feared ‘Bouncing Betty’, exploded at waist height and came to be nicknamed ‘castrators.’

The enemy could well be- and, sometimes, were- women and children.

The result, in the words of Bernd Greiner, was that “lecherous passion lay like a thin varnish over disappointment, hatred and fear, over the frustration of those who wanted the unreasonable, expected the impossible, and of course repeatedly failed in their attempt to reassure themselves of their soldierly masculinity through bought or forced sex.”

That the stateside sexual revolution manifested itself in the form of indefensible sexual exploitation in civilian areas of Vietnam was a particularly ugly development in an increasingly grotesque war.

Returning to the Grunt Free Press, in response to a later question pertaining to the existence of a generational gap in Vietnam, the student interviewee states that “only a young man can have the imagination and daring to make the necessary changes.”

When the interviewer queries about what changes the student has in mind, it becomes clear that, although the Vietnamese hippie movement was coloured to a greater extent by wartime frustration, tradition and family influence than the parallel redoubts of flower power over in the West, it was no less questioningly iconoclastic in vision. The hippie mantra of ‘trust nobody over thirty’ appeared to morph into ‘trust nobody in a uniform.’

STUDENT: First, let me say this. We are anti-communist and we are anti-war. We have seen what the communists did during Tet and we do not like it. And we believe that the U.S helped the VC (Vietcong) during Tet to force a coalition government on us. After all, why were all the big targets during Tet all Vietnamese?

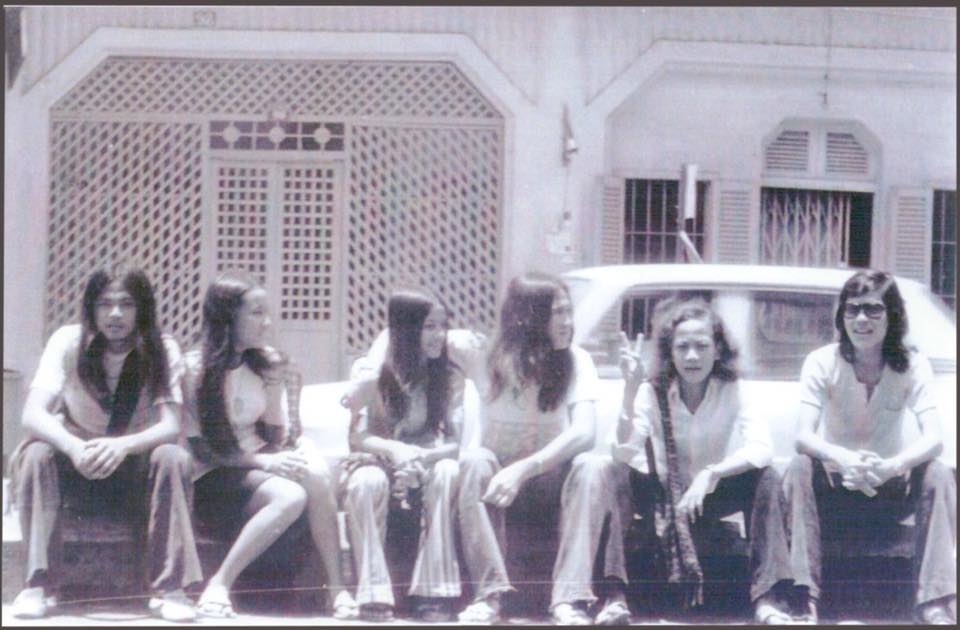

Even so, was difficult for the Vietnamese anti-war movement to know which warring faction to focus their ire upon, leading to some ambiguity in countercultural motifs. The CBC Group, in their flared jeans, granny glasses and floppy wide brimmed hats, were unquestionably bona-fide hippies of the Haight genus, so it was only natural that they wore American style clothes and superficially resembled American hippies.

On occasion, they were photographed wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the U.S flag. It is difficult to ascertain whether the band- who came to be known for the broken peace medallions they wore in protest against the ongoing war, and who developed a particularly strong affinity for anti-war musical material such as the Grand Funk Railroad composition ‘People, Let’s Stop The War’- donned the American flag as a means of subversion or support. After all, it wasn’t rare for the band to cover Country Joe and the Fish’s ‘I Feel I’m Fixing To Die Rag’ (a darkly humorous anti-war song that invites American fathers to send their sons to Vietnam to “be the first one on your block to have your boy come home in a box” and featuring a repeated, comically nihilistic refrain of “Whoopee! We’re all gonna die!”) during their live sets.

Adding to the abstruseness, some of the band’s lexicon was inherited not only from the counterculture but from the U.S military itself, as is apparent within the contents of a 1971 tape produced by the group. Loan, introducing herself as “the little lady up front,” decides between songs to “take a little time to let them know who we are.” In a group that had always been very much a family affair, she first calls her 14-year-old brother, Van, the CBC band’s drummer. “Come over here, little brother Van,” Loan is heard to prod, “Say something, little brother.”

“Lifer, lifer, lifer, so many lifers, where do they come from?” Van says playfully. “I hope they go back. Dig it.” In the language of Vietnam-era grunt slang, a ‘lifer’ denoted a career soldier, someone who likely enlisted before the war and would in all likelihood remain after their tour of duty. Maybe CBC intended only to imitate, so as to further endear and relate themselves further to the military men they performed to- or, perhaps, they were repurposing the language of war into the language of peace.

The latter theory has some weight since the rest of the band’s rhetoric is intrinsically peacenik. “Peace, man, that’s all I want, that’s all I say,” insists Hien. The other Hien in the band, nicknamed ‘Hien Rhythm’ due to his role within the band as rhythm guitarist, warmly asks “What’s happening, brother? Let’s get our stuff together, brothers, man, it’s the way.” When Loan introduces Linh, she dubs him the group’s leader and a ‘lifer.’ “Come here, lifer, say something.”

“Wow, talk, talk, talk,” Linh responds, “only talk, no music, man. Talk tires me, music blows me. Right on.”

The “little lady up front” concludes the band’s introductions by explaining that “I just want to let you know that we all love you, man.”

No matter their allegiance, the non-violent stance of the group was obvious. It is no coincidence that Linh and his wife Mary Louise came to be playfully referred to as ‘Vietnam’s John and Yoko.’ For this they drew the wrath of masters of war on all sides.

After all, if anti-war protest was a dangerous business 8,300 miles away in the United States, (as Kent State University’s class of 1970 can attest) it certainly carried its own risks within South Vietnam’s embattled, crumbling society. Take the example of the most vocal anti-war musician in South Vietnam, the poet Trịnh Công Sơn, who was dubbed the ‘Vietnamese Bob Dylan’ by Trần Văn Dĩnh in the November 8th, 1968 edition of Peace News. His compositions- which drew a sizeable audience amongst South Vietnamese students and intellectuals- are notable for the idealism buried within their bitterly pacifistic content.

Whilst he was influenced by the American protest movement, his songs vary from those of his American cousins in that he seemingly possessed no loyalty to either of the warring parties. Instead, he boldly voiced his desire for Vietnamese reunification at any cost- and under any government.

Increasingly, the Western protest movement condemned the U.S war effort with growing intensity whilst lionising the North Vietnamese/Vietcong cause. The underground press sold ‘Vietnam Papercut’ posters that sought to donate proceeds to the NLF, and John Lennon was seen wearing a T-shirt embellished with a Vietcong flag in 1971. Most notoriously, 1972 saw Jane Fonda photographed with a North Vietnamese anti-aircraft crew in Hanoi. The overriding emotion in Trịnh Công Sơn’s music, however, was not one of radical anger. Instead, melancholic condemnation of the wastefulness of conflict, married with idealistic optimism for Vietnam’s post-war future, characterised Trịnh’s ruminations.

In ‘Song about the Corpses of People,’ he memorialises the 6,000 civilians purged by Communist forces in the Huế Massacre, regarding each victim as a cherished member of a wider family whilst hoping that their bodies would live on within the soil that had reclaimed them. In ‘It Is We Who Must Speak,’ Trịnh depicts Vietnam’s civil war as fratricidal and calls for unification irrespective of ideology. Meanwhile, he came under pressure from the South Vietnamese government when it was feared that his song ‘Lullaby,’ about a mother grieving for a son killed in battle, might damage the already dwindling morale of the ARVN.

The Vietnamese casualties of the war were not divided by faction within Trịnh’s lyrics, perhaps most markedly within ‘Who’s Left Who Is Vietnamese.’ Penned at a time when total Vietnamese deaths had surpassed one million, he implored combatants to turn over the corpses that littered the countryside, look beyond the uniforms they wore, and realise that they could only see Vietnamese faces.

In 1975, as the Republic of Vietnam lurched into its death throes and North Vietnamese victory appeared imminent, Trịnh was jubilant. He took to South Vietnamese radio and performed his 1968 song ‘Joining Hands/Circle of Unity,’ declaring that, after hundreds of years of endless war, reconciliation was now Vietnam’s inevitable fate. Perhaps there could be peace at last for the battle-scarred nation.

Nonetheless, despite Trịnh’s even-handed criticism of the war, the North Vietnamese victors could not look past the Western influence of his music- not to mention his less than complimentary depiction of the HuếCity Massacre. Although he would eventually come to be revered within Vietnam (his 2001 funeral drew hundreds of thousands to the streets of Ho Chi Minh City) Trịnh Công Sơn spent the first few years of Vietnam’s reunification in a labour camp where he had been sentenced to be ‘retrained.’

The writing had been on the wall for South Vietnam since 1971, a year that was to prove a crucible for CBC. Under the policy of ‘Vietnamisation,’ U.S troops were gradually withdrawing from combat roles, leaving a greater challenge for the ill-trained and equipped South Vietnamese army to overcome. With this greater responsibility came higher casualties and a renewed need for more manpower to throw into the meat grinder. That February, ARVN forces staged an incursion into Laos in an effort to harass enemy troop formations infiltrating into South Vietnam, via the notorious Ho Chi Minh Trail. It was code named ‘Operation Lam Son 719’, and it was a bloodbath.

One U.S veteran remembered how “my people stood on the side of Route 9 and watched the trucks with grinning 18 and 19-year-old ARVNs rolling into Laos. A month later, we watched the survivors rolling back out. Truck after truck filled with 40, 50, 60 kids, nearly every one of them messed up; kids missing arms, legs, half their faces in bandages, but so help me, still waving and grinning at us. I couldn’t look after the first convoy.”

Against this blood-spattered backdrop, Linh and the two Hiens, military aged males, came under repeated pressure to enlist for the very military that had harassed them for their long hair and pacifistic sensibilities for most of their career. All the while, the reality of war crept ever closer to the refuges of Saigon’s counterculture.

On April 8th, 1971, the CBC Band were performing at the My Phuong Club in downtown Saigon’s To Do street. It initially seemed to be like any other of CBC’s multitude of gigs.As always, Loan opened proceedings with the banshee proclamation that had echoed through all too many smoky Saigon venues.

“Yea, we’re the CBC Band, and we’d like to turn you on… We got a little peace message, like straight from Saigon. Waaaaaah yeah!”

Like a well-oiled machine, the band launched into their blazing rendition of Hendrix’ ‘Purple Haze.’

As they hammered away at the pulsing opening riff, there was a deafening boom and a blinding flash. The band seemed to disappear from sight.

“One minute we’re sitting at a bar table, next moment blown away, covered in debris, pitch black darkness, in complete silence. But the silence lasted only a few seconds,” Air Force veteran Scott Roberts remembered. “Then we heard the screams of a bar girl and shouts for help. Then total chaos.”

Michael Janus had just returned from patrolling the jungles with an infantry unit and had hoped his period of R&R in Saigon would offer some light relief. Instead, he was caught up in the pandemonium within the My Phuong Club.

“When the bomb went off, I lost my glasses, my hat,” he said. “I was one of the first ones to get out. I had a wound in the spine. Perforated ears. My ears still ring.”

Whilst the band emerged unharmed, the audience were not so lucky. One American G.I and one Vietnamese woman- Phan Van’s girlfriend- were killed, and an undetermined number of others were wounded in the bombing. The Vietcong- who had so often bemoaned the decadence of Western popular music- had directly targeted the CBC Group.

Shaken but not stirred, the band- and the wider Saigon counterculture-were undeterred.

“In Vietnam today, there is a war and we must expect controls,” Linh told Grunt Free Press in 1970. “But I hope when it is over, we can be as free as young people everywhere. I hope that one day, we can have a Woodstock in Saigon, maybe in the Zoo, with some rock groups from America and England playing together with us. It would be the greatest day in Saigon- for our young people and your young G.Is.”

“Yeah, man,” interjected a U.S soldier. “Like, they ought to give Bob Hope and Billy Graham a year off and send us the Doors or the Jefferson Airplane or the Mamas and Papas.”

The August 1969 Woodstock Festival was certainly a powerful and omniscient symbol. Bordering on sacred within the international counterculture, it had already become an event of mythic status, a legend in its own time, a viable case study for the alternative society that the counterculture aspired to.It is hardly surprising that the CBC Band, born amidst one of the twentieth century’s most violent conflicts, looked expectantly at the formula perfected by this peaceful three-day long Aquarian exposition. Joni Mitchell’s oft-covered tribute to the festival had, after all, featured the prescient and tantalising imagery of bombers turning into butterflies in the sky, all thanks to the love power generated by a gathering of kindred tribes.

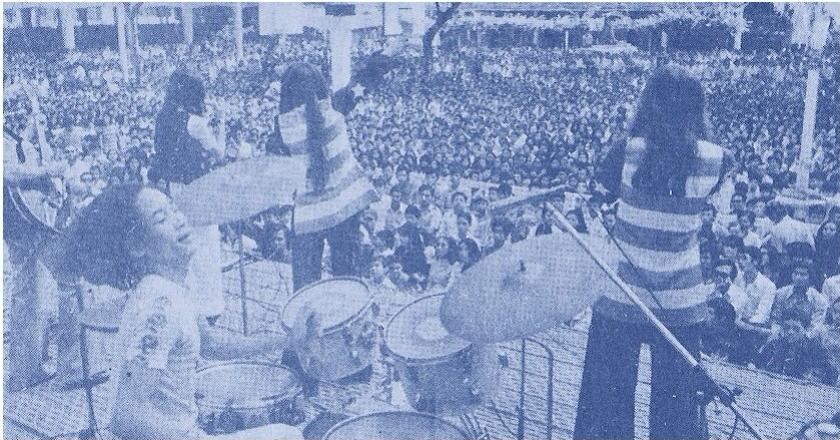

On May 29th, 1971, only one month after the bombing in Tu Do street, Woodstock came to Saigon Zoo.

As was by now the norm within the Vietnamese counterculture, the Saigon International Rock Festival held at the city’s zoo was riddled with idiosyncrasy and paradox. For a start, proceedings were organised, sponsored and promoted by some of the most pro-war echelons of South Vietnamese society. Dieu Hau, a weekly magazine staffed predominantly by ARVN officers, was particularly outspoken in their support of the festival, and proceeds were to be donated to the South Vietnamese Army. The first of a several such concerts eventually held at the Saigon Zoo, the festival was, unfortunately, set to fuel the war that the CBC Band so earnestly wanted to end.

Of course, there were the by-now typical debates about the incompatibility of counterculture with Vietnamese tradition, about bastardised national identity and cultural imperialism, whilst North Vietnam derided the festival as “a scheme to morally poison Southern youths.” But, for the 7,000 who crowded into Saigon Zoo that day in May 1971, it was a celebration of individuality, participation, emancipation even. “The fact that it’s here at all,” explained one American news outlet, “underlines the lust of the urban youth here to join with other youths across the world in enjoying the freedom, even the license, of the youth culture.”

“About 500 G.Is attended,” journalist Gloria Emerson reported, “many wearing headbands and anti-war or Black Power jewellery.” Noting the proliferation of Vietnamese youth who comprised the majority of the audience, she added that “it seemed that many of them- with their long sideburns, far-out sunglasses, open skirts and flared trousers- might want to be hippies, but that life in South Vietnam did not permit it.”

Even amidst the euphoria of Vietnam’s first rock festival, the sights and sounds of war were inescapable. ARVN officers scattered throughout the audience monitored proceedings, their red berets, camouflage uniforms and dark sunglasses incongruous with the surrounding would-be flower children. At one point, during a momentary lapse in the music, South Vietnamese soldiers were invited onstage to receive decorations for combat valour.

However, at times, the Saigon International Rock Festival did manage to revive some of the fleeting magic that had been spent at Woodstock two years earlier. A number of Vietnamese bands shared the stage with groups from Australia, Japan and the Philippines, and elsewhere. When it rained, as it had done so famously at Woodstock, Gloria Emerson saw “G.Is and Vietnamese huddled together under the big umbrellas on the festival grounds or inside tents put up by the army, many of them laughing at how wet they were.”

What little footage survives of CBC’s performance at the festival they had planted the seeds for preserves a band in fiery form. Buoyed by muscular guitars, Loan bops feverishly around the stage, her long dark hair cascading over her face. In her red blouse, pinstriped vest and matching flares, she almost resembles Janis Joplin in both appearance and intensity. As she wails out her siren song, the camera captures young Van, face steeled with concentration and long hair bouncing as he carves out a lean pounded path for the band on the drums. Even though Saigon’s beautiful people remain as still as ever, the stage is alive with energy.

It could almost be Woodstock. For an all-too brief moment, this wasn’t a war. It was a happening.

But peace and love did not win through. The bombers riding shotgun in the sky did not turn into butterflies. The war dragged on. And, with the gradual withdrawal of American forces in the early 1970s, the impetus was slowly passed to the North Vietnamese. The wave that the CBC Band had been riding was receding in tandem with the fortunes of war.

They appeared to recognise this themselves. Towards the end of 1971, the CBC Group put together a tape recording of some of their most renowned covers so that departing U.S soldiers might have a souvenir of the sunny moments they spent with the band in the defilade of an atrocious moment in history. During the tape, Lien explains with muted sentimentality:

“Well, I just want to say that someday I hope you will play this tape and you will think of us and the good times we all had together, okay?”

Over the course of the recording, the group shine as brightly as ever. Their cover of Black Sabbath’s ‘Paranoid’ is pure fire and brimstone. The audience can be heard to cheer as they carry out an emphatic attack on Santana’s ‘Soul Sacrifice.’ Linh blasts his way once more through ‘Purple Haze.’ Elsewhere, their selections are fresh from the charts, with covers of recently released album tracks by the James Gang and Grand Funk Railroad. Yet, there is a feeling of pensive sadness- perhaps even resigned betrayal-soaking the superficially jovial proceedings. It feels like a bookend to CBC’s taste of hippiedom.

Loan’s a Capella rendition of Janis Joplin’s ‘Mercedes Benz’- replete with an endearing attempt at Joplin’s Southern drawl- feels more like a rebuke in such a context, like a subtle jab at the big-spending U.S servicemen, the non-essential luxuries they brought with them to Vietnam, and their complicity in the poverty-inducing devastation the armed forces left in their wake.

“Oh Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz?

My friends all drive Porsches, I must make amends.

Worked hard all my lifetime, no help from my friends

So Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz?..”

Then, when Loan sings ‘It’s Too Late’ from Carole King’s ‘Tapestry’ album, the words seem recontextualised by the Vietnam experience. It transforms into a song about the faltering U.S war effort- without which the Republic of Vietnam was doomed to topple- and the short interlude of hope that Saigon’s doomed counterculture provided to the youth who found solace in it.

“And it’s too late, baby now, it’s too late

Though we really did try to make it

Something inside has died, and I can’t hide

And I just can’t fake it…”

It is clear the band wish to create a time capsule, not only for the departing American troops but also for themselves, a record of the tumultuous 1960s and 70s when they were almost famous. This is particularly clear with the brief medley of three early Beatles songs, none of which by this time had troubled the charts for five years or more. In performing ‘A Hard Days’ Night,’ ‘And I Love Her’ and ‘Act Naturally’ on the tape, Linh preserves in ether the early Beatles records that had so enthused and inspired him in the simpler days of the mid-60s.

It is fortunate that some of CBC’s music has survived. Many of the bands that comprised the Saigon scene- not to mention their recordings-have subsequently vanished in the haze.

This is, in part, attributable simply towards differing attitudes towards recorded music in Vietnam. Like several other Asian cultures in the 1960s and 1970s, records were recorded, consumed and disposed of in fairly quick succession. Collectors in hot pursuit of Vietnam’s elusive rock and soul singles from this period are often misled when shop owners and producers explain, quite truthfully, that “we threw it away.”

There is also a more ominous note to the conspicuous silence of Vietnam’s musical past. As Mark Gergis explains, “Saigon fell to the Vietcong in 1975. Popular music reflecting the West was completely banished. For those South Vietnamese that couldn’t flee, it became prudent to destroy all remnants of Western cultural affiliation. Photos, books, documents and music were often destroyed by their owners before the Vietcong could discover the evidence and send offenders to ‘reform camps.”

The reality is, some of the voices featured on Sublime Records’ ‘Saigon Rock and Soul: Vietnamese Classic Tracks 1968-1974’ compilation could very well be singing from beyond the grave.

In 1974, with the red tide sweeping down from the North and the South Vietnamese domino on the brink of falling, the CBC Band- having been tipped off by a friend with CIA contacts- staged their exodus. The fall of Saigon was imminent, and CBC were a band on the run.

When the men’s visas ran out, they journeyed their way through Malaysia and Bali before eventually settling in a Tibetan monastery in Northern India. Stripped of the instruments that had lent them their power, they still took comfort in music they were able to play. As North Vietnamese tanks crashed through the gates of the U.S embassy in Saigon, NBC captured CBC performing a new composition they had hastily penned about their situation. Van tapped out a rhythm with sticks and Linh strummed gently on an acoustic guitar as Loan led the family band in song:

“We love the South and we love the North,

We love our music and for this we ran.

Our land was Vietnam.

We just want to see our people free….”

But Saigon was no more. Ho Chi Minh City now stood in its place.

The band eventually made it to the United States towards the end of 1975, in part thanks to the monetary assistance of a network of G.Is who had been fans during their heyday. The Inter-Agency Task Force on Indochinese Refugee Resettlement oversaw their move to Fort Wayne, Indiana, and, after purchasing new electric instruments in Chicago, the CBC Band were once again on their feet.

In one photograph from this time frame CBC are captured astride a dirt road holding up a sign that reads ‘Filmore.’ The Fillmore West, where San Francisco’s first wave of psychedelic bands had blown legions of minds and sown some of the world’s first flower children, had closed four years earlier. The Age of Aquarius was over, and America had moved on from its daydream. In their hippie attire, CBC were refugees not only of a country that had ceased to exist, but also of a dead zeitgeist.

Eventually settling in Houston, Texas in the early 1980s, the group staked out a healthy career as a cover band. Whilst picking up a litany of new material over the passing decades,it was the songs of the 1960s and early 1970s that remained the touchstones of their oeuvre- and rightfully so.

After all, whilst the songs of the Rolling Stones, Creedence Clearwater Revival and Buffalo Springfield remain synonymous with the Vietnam War, persevering in painful collective memory and Hollywood depictions of the war alike, the CBC Band were right there in the midst of the trauma, blood and mire. They brought the shindig to the abattoir, and lived to tell the tale.

And, almost fifty years since the Tu Do Bombing and the Saigon International Rock Festival, fifty years since that terrible war, few moments capture the defiance, the beauty and the sorrow, of the CBC Band so powerfully as the final moments of that taped set from late 1971.

As an organ plays the elegiac opening notes of John Lennon’s ‘Imagine,’ Loan takes to the stage to offer a final, counterculturally-tinged farewell. The room takes on a reverential silence, and only Loan’s voice echoing through the venue’s sound system and the softly rendered melody of Lennon’s paen to peace can be heard.

“As you all sometime soon will be leaving the ‘Nam and heading back to the world,” she sermonises, “we hope that you will take with you the understanding that someday, somehow, we must all come together as brothers and sisters- bound together in the name of humanity to bring forth a peace universal to all.”

– Jack Hopkin

CBC Band Facebook

Sublime Frequencies Official Website

Michael J. Kramer about CBC Band

All photo materials are copyrighted by their respective copyright owners, and are subject to use for INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY!

Jack,

Nice exploration of the lives and music CBC Band. Someone needs to make a film about them!

It’s quite a story, from their time in Vietnam during the country’s civil war and American occupation to their stateless wanderings through Bali and India. to their long career in the States, from the Ramada Inns of the Midwest to Houston, where they now sometimes perform for Vietnam veteran reunions.

I just wanted to add that if readers want to explore aspects of CBC’s story more, in addition to the chapter about them in my book, The Republic of Rock, the essays of musicologist, composer and bassoonist Jason Gibbs on Vietnamese music and the fiction and scholarship of Viet Thanh Nguyen are but two authors among many worth reading. And there’s more research still to be done on all this if you ask me. Also, for one of the most revealing historical studies about the American GI experience of the Vietnam War as a war of occupation in which US consumer culture mattered as much, maybe more, than “humping through the jungle,” check out Meredith Lair’s Armed with Abundance: Consumerism and Soldiering in the Vietnam War. I learned a lot from that book.

Thanks for your work telling CBC’s story and pondering the significance of those global sounds of youth culture hippie rock that helped to give flickering shape to what Mark Gergis calls Pax Countercultural and I call the Woodstock Transnational—that strange, late 60s/early 70s stateless state of becoming many young people dreamed of joining amid the highs and lows of the era.

Michael

Hi Michael,

I’m glad you enjoyed the article! You’re right- CBC’s story would make for an excellent film, theirs was a fascinating career that far too few in the West are familiar with.

I’d also like to thank you for your work on the subject. ‘The Republic of Rock’, alongside your writings online, were key sources and influences not only for this article, but also for my university dissertation (which focused upon the global counterculture’s impact on the progression of the Vietnam War).

Thanks again!

Jack

Great article! Thank you very much Jack. And I agree this story is very suitable for screenplay. Such breathetaking as the story of American psychedelic band The Misunderstood from ’60s.