Museo Rosenbach | Interview

Museo Rosenbach formed in the early seventies and released ‘Zarathustra’ in 1973. Their debut is regarded as one of the best Italian progressive rock works of all time.

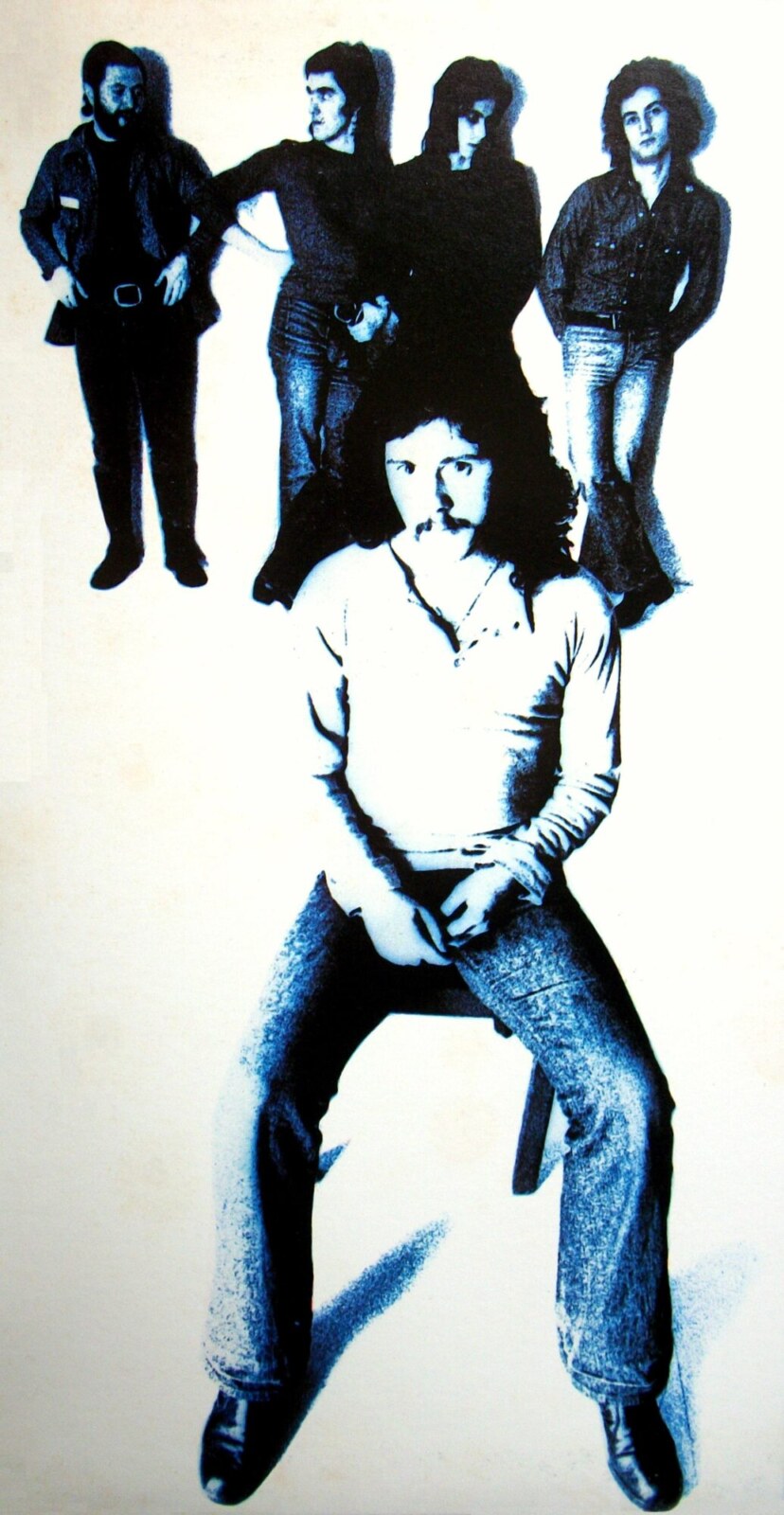

1973 ‘Zarathustra’ Museo Rosenbach is:

Alberto Moreno (bass, piano)

Stefano “Lupo” Galifi (vocals)

Enzo Merogno (guitar, vocals)

Pit Corradi (Mellotron, Hammond organ, vibraphone, Farfisa electric piano)

Giancarlo Golzi (drums, timpani, bells, vocals)

2000 ‘Exit’:

Alberto Moreno (bass)

Giancarlo Golzi (drums)

Andrea Biancheri (vocals)

Marco Balbo (guitars)

Marioluca Bariona (keyboards)

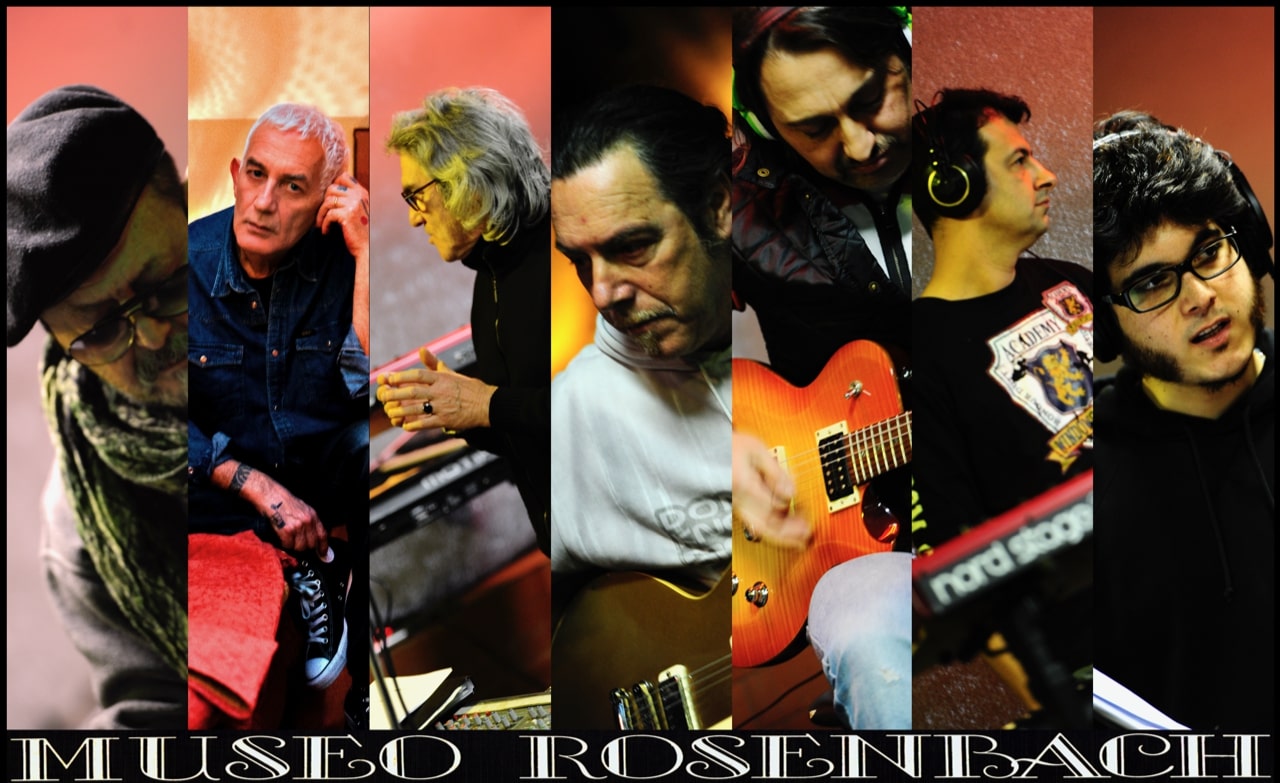

2013 -2014:

Stefano “Lupo” Galifi (vocals)

Giancarlo Golzi (drums, timpani)

Alberto Moreno (keyboards)

Max Borelli (guitar)

Sandro Libra (guitar)

Fabio Meggetto (keyboards)

Andy Senis (bass & vocals)

“It was an articulated message that dealt with rather challenging issues”

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

Alberto Moreno: I was born in August 1951 in Bordighera, a coastal town in Liguria, a few kilometers from the French border. I studied in Milan and graduated in Philosophy in 1976. I have always had my residence in Bordighera but I have lived for years in Milan and Rome. I grew up in a music environment. My father was an avid listener of jazz music … Chet Baker, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, and Dixieland in general. I spent Sunday afternoons lying on the floor among the covers of the records that my father bought especially in nearby France. My uncle, on the other hand, made me listen to classical music, practically all the well known repertoire. The musical shock, at ten, were the soundtracks of the films ‘Exodus’ and ‘West Side Story’. Then the era of the Beatles and Bob Dylan began.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

At the age of seven I started studying piano but I stopped in my teens to learn the acoustic guitar. Of course I tried to play the hit songs of the time … the first Italian beat music and the English and American hits. When I formed my first musical group which was called ‘The Polythropes’, I switched to bass and my role model became Paul McCartney.

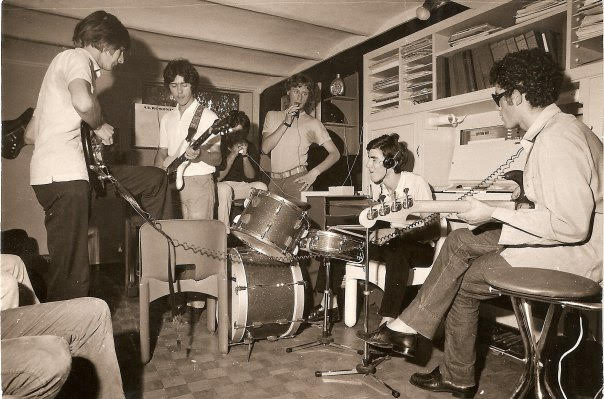

After a few months the band turned into ‘The Peanuts’. Giancarlo Golzi was already on the drums and the lead guitar was played by Pit Corradi. The singer was Marco Biancheri. The repertoire was varied from The Animals to the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Spencer Davis. We even played some Monkees songs. We often made short performances in the clubs of Sanremo, in competitions for bands and in restaurants.

What bands were you with prior to the formation of Museo Rosenbach?

Before Museo Rosenbach there were other formations. After the Peanuts there was ‘The Moonsound’, a band that did not last long but played Jimi Hendrix and Cream. There were three of us … Golzi, Corradi and me. But a singer was missing because Biancheri was in military. We rehearsed in the cellar with occasional singers, but it was not possible to play in public. In 1970 the ‘Quinta strada’ was born. Biancheri returned from the military service, but we also wanted to have a keyboard player now. I bought myself a Farfisa Professional Duo and we found a bass player we called “Calore”. I don’t remember his real name because he only stayed with us a few months. By now our repertoire was expanding. The repertoire consisted of ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’ by Iron Butterfly, but we also played Santana, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and others. As ‘Quinta strada’ we never played our compositions. However, I began to rehearse some sequences of piano chords which later became the nucleus of songs on ‘Zarathustra’ album.

Can you elaborate on the formation of Museo Rosenbach?

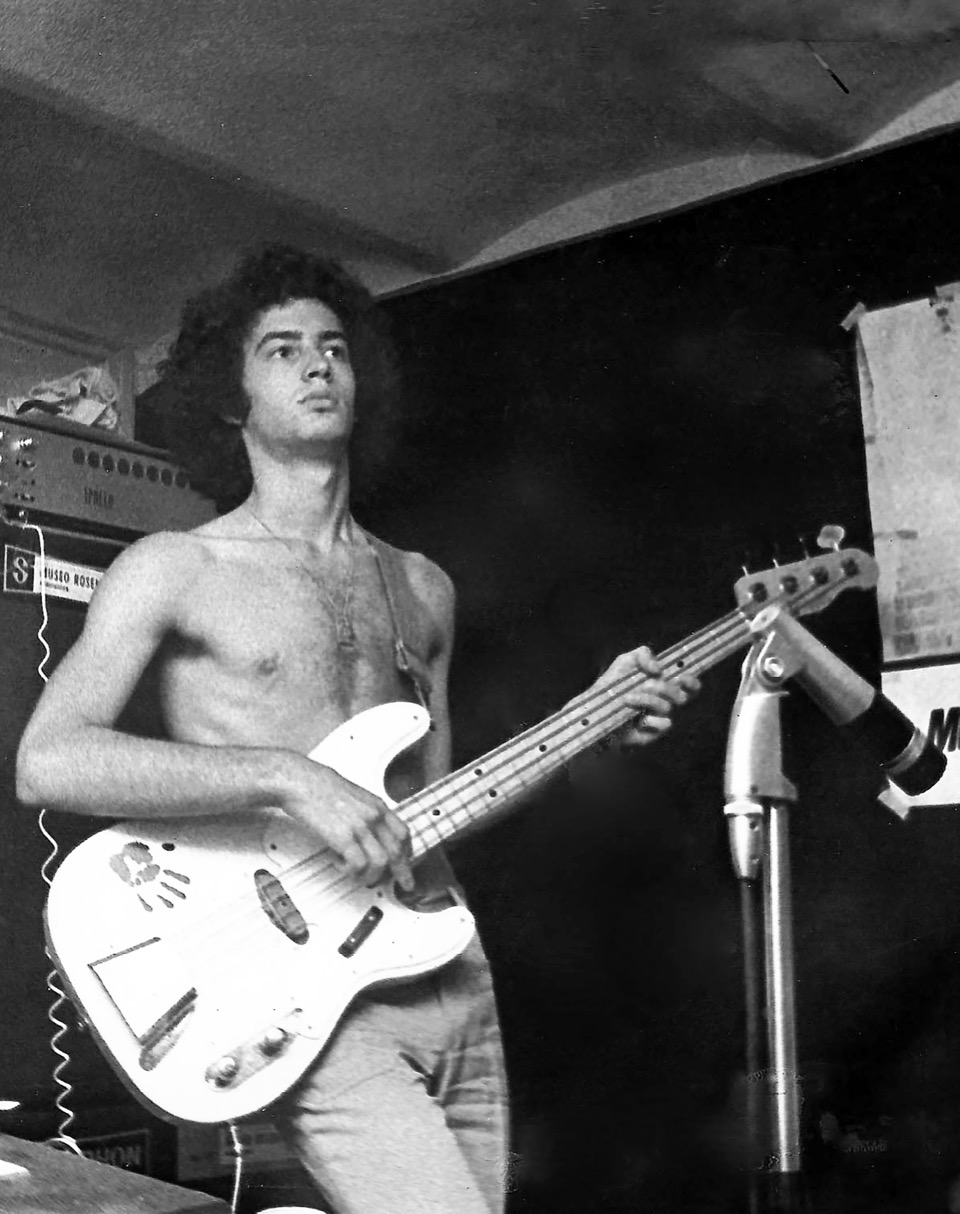

‘Quinta strada’ stopped. There were some changes in the lineup. The reasons are to be found in the changeability of youth experiences, in the dynamics of friendships and also in the different musical choices. We wanted to get out of the simple execution of the successes of others. The drummer was and always remained Giancarlo Golzi, but Pit Corradi bought a Hammond L100 and dedicated completely to the organ. I bought a white Fender Telecaster bass and went back to my first instrument. From the dissolution of a band from Sanremo, ‘Il Sistema’ we inherited a guitarist, Enzo Merogno, and Leo Lagorio who played sax, flute and was also an excellent pianist. The intentions became serious. We faced ‘Valentyne Suite’ of which we performed the first part, then songs by Cressida and King Crimson. We began to rehearse some of my compositions as well. The singer was missing. Biancheri was no longer available for work reasons. Pit Corradi had moved to Genoa but continued to participate in the rehearsals that took place over the weekend. One Saturday he showed up with Stefano “Lupo” Galifi, a nurse from Genoa who sang rhythm and blues. I was perplexed. However we did a small audition. He sang ‘It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World’ and ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’. We were struck by the bluesy timbre of his voice. We decided to try one of our compositions, the one that later became ‘Dell’Eterno Ritorno’. The effect convinced us. The mixture of the blues voice with a decidedly rock sound worked. Lupo joined the group and we began to develop my ideas. We also worked on ‘Della Natura’. I had written the opening riff for Lagorio’s sax. In this song, Lupo’s timbre blended better. Thus was born the Museo Rosenbach in the version with the sax. When we decided to try to record a record, Lagorio, who worked in an oil industry, pulled back. The intro of ‘Della Natura’ was adapted to Corradi’s Hammond.

How did you decide to use the name “Museo Rosenbach”?

In Italy there were bands with very long names: Premiata Forneria Marconi, Banco del Mutuo Soccorso, Raccomandata con Ricevuta di Ritorno (Raccomandata Ricevuta di Ritorno) etc. After long discussions someone proposed “Museo delle menti umane” (Museum of human minds). We moved on to “Inaugurazione del Museo delle menti umane” (Inauguration of the Museum of Human Minds) … It was too long! Then “Inaugurazione del Museo” (Inauguration of the Museum). I suggested adding a name. I came across a book in English by Otto Rosenbach, a publisher of old books. We liked the surname, especially for its meaning in Italian “Ruscello di Rose”. We reached an almost final agreement: “Inaugurazione Museo Rosenbach” (Inauguration of the Rosenbach Museum). We get rid of the term “Inaugurazione” and became just Museo Rosenbach.

“When we worked on our songs we tried to capture our own passion and build an original sound.”

What influenced the band’s sound?

That’s very easy to answer … Gentle Giant, King Crimson, Genesis, Van der Graaf Generator, Jethro Tull, Procol Harum … Each member of the band had their passions. Corradi had been a lead guitar and therefore he adored Jimmy Page and Hendrix, Enzo Merogno played in beat bands and his guitar style had developed with previous band, Il Sistema, which had already elaborated complex compositions with themes taken from classical music (Mussorgsky’s ‘Night on Bald Mountain’) and from the repertoire of Nice. Golzi was a rock drummer who knew how to adapt to any genre. He loved Elton John, Michael Giles, The Beatles. Lupo listened to James Brown and Chicago. I am a “mannerist”, I assimilate the most diverse musical genres: classical music, soundtracks, Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan … and I could go on. When we worked on our songs we tried to capture our own passion and build an original sound. The result was very similar to Banco’s music also for the themes of the lyrics we were writing.

How did you get signed to Ricordi Records?

We were very lucky. We sent a demo to Ricordi only because it was Banco’s record company. Three days passed and we were summoned to Milan. They entrusted us to an artistic producer, Angelo Vaggi, who took us to a small room. He asked us to play the demo we had sent. The result was convincing for him. Ricordi offered a three-disc contract over three years. Obviously, we accepted with enthusiasm. All this happened in the first months of 1973. We stayed in Milan to get ready and in April we entered the room.

“A series of dialogues between the common man and the prophet”

What’s the story behind the ‘Zarathustra’ album from 1973? Where did you record it? What kind of equipment did you use and who was the producer? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

Before ‘Zarathustra’ there were songs. In the rehearsal room we created the individual pieces with a text in very rough English. He was interested in the sound and we were very attentive to the opinions of the many friends who followed us. I proposed the theme, performed on the piano; the others began to transform it by adapting it to their instruments. Each piece was performed in numerous versions: short version, addition of bridge between verses, changes of speed and atmosphere. Gradually we came to a version accepted by all. In the first months Museo Rosenbach still performed some covers, but in each concert we inserted our own composition to see the effect on a wider audience than the circle of friends. When we reached a number of songs suitable for a long play recording we asked ourselves what world we wanted to represent. At this stage, the label proposed the character of ‘Zarathustra’. The songs took the form of speeches by this prophet: ‘Dell’eterno ritorno’ (Of the eternal return), ‘Della natura’ (Of nature), ‘Al di là del bene e del male’ (Beyond good and evil). The concept took shape like this. Merogno who came from Il Sistema remembered a theme that had been developed by that band. We worked it out to fit it into what was becoming a mini suite. We integrated it with some of our ideas and it became ‘Il Tempio delle Clessidre’ (The Temple of the Hourglasses). There was an “incipit” missing … I wrote the intro and ‘L’Ultimo Uomo’ (The Last Man). The motif of this piece was resumed at the end of the suite.

Before recording the demo to be sent to Ricordi, we replaced a song called ‘Dopo’ with a guitar and organ riff. I added the sung part and we called the new composition ‘Degli uomini’. We were ready for the demo.

The recording took place in two weeks in the Ricordi room in via dei Cinquecento in Milan, an old cinema converted into a recording studio. We recorded on 8 track recorder. First the drums, the bass and a lead guitar; later we added keyboards and more lead guitar. Finally sang Lupo. In the hall we came up with the idea of creating a series of dialogues between the common man and the prophet in the mini suite ‘Zarathustra’. In the first song the opening verse is sung by a dear friend of ours, Walter Franco, in ‘Il re di ieri’ intervened with Giancarlo Golzi, and in ‘Al di là del bene e del male’ we all sang to convey the idea of a group of priests. We left Lupo the part ‘Il Superuomo’ because at that moment Zarathustra was expressing the core of his message.

We recorded with our instruments with the addition of a grand piano supplied in the room. One afternoon I sat down on the piano; I began a sequence of very arpeggiated chords. Our producer, Angelo Vaggi, decided to include it in the suite to create a moment of classic ambiance. I was very happy with it. The sound engineer was a professional used to recording pop music. He was a bit bewildered by the song structures but after a couple of days he collaborated constructively. After fifteen days in the theater there was a week of mixing in the room in via Berchet. That was a moment of nervousness because we were young and inexperienced. Each wanted to emphasize their instrument. Luckily Vaggi was able to mediate and the album was ready for distribution.

“We considered him [Zarathustra] a prophet who fought against hypocrisy, power and war, the destruction of nature.”

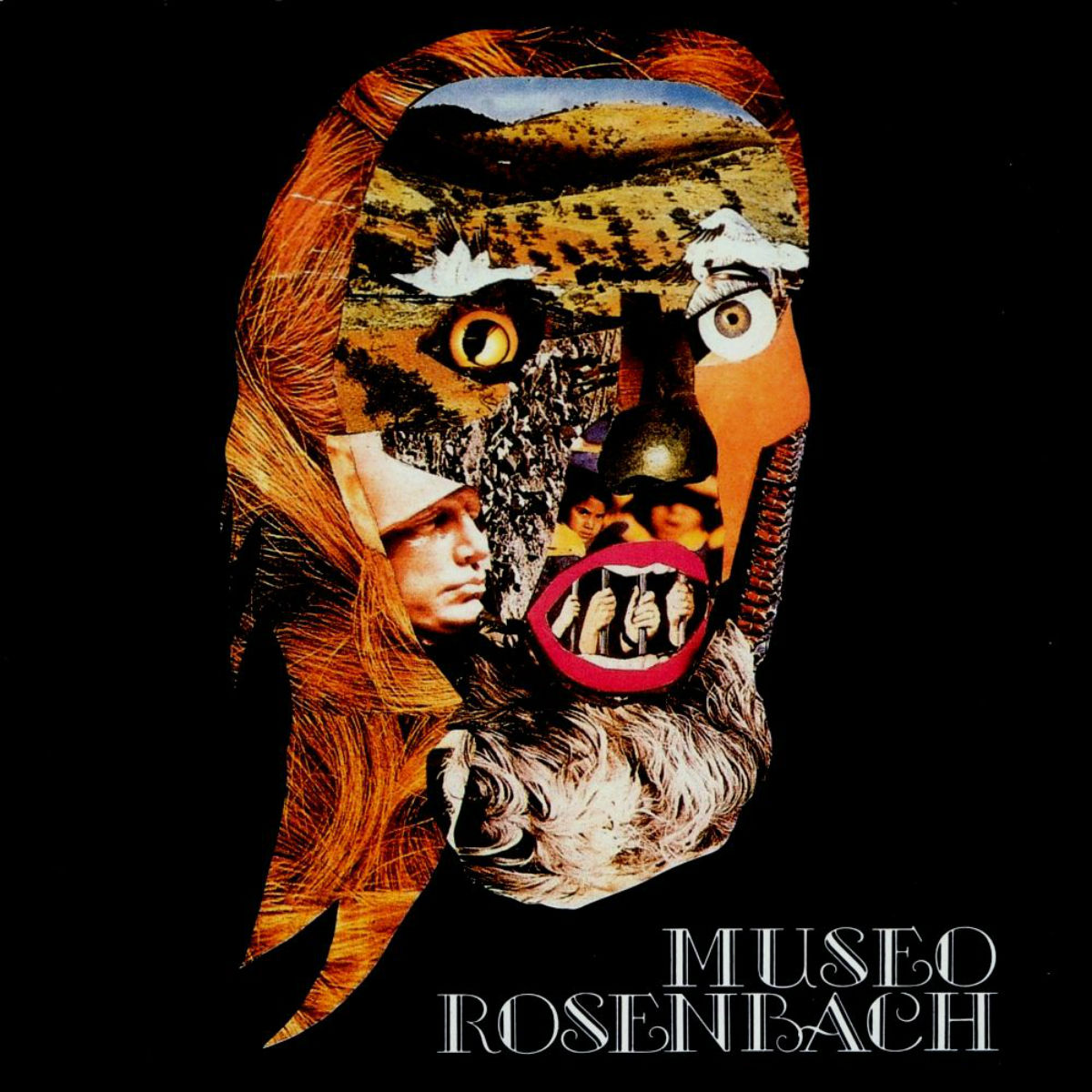

Ricordi focused heavily on Zarathustra from a promotional point of view. Unfortunately he made the mistake of inserting the bust of Mussolini on the cover. The times were highly politicized. The black cover, the bust of Mussolini, the concept derived from a text by Nietzsche, then mistakenly considered a precursor of Nazism, made our life difficult. Considered as a “fascist” band we were censored almost immediately by the radio. No one has read with attention and the desire to understand the long text that we have included in the album in which we explained our “reading” of the character of Zarathustra. In fact, we considered him a prophet who fought against hypocrisy, power and war, the destruction of nature.

We were inexorably labeled. We performed the record at the “Festival of New Trends” in Naples in June 1973, and in some concerts in Italy during the summer and autumn. However, we were discouraged by the controversy and troubled by the tensions within the band; we therefore decided to dissolve the group. This is how the adventure of the first Museo Rosenbach ended. Golzi left in the military and later became the drummer of Matia Bazar, I graduated in Philosophy and began teaching, Corradi became an architect in Genoa, Merogno opened a pharmacy and Lupo continued to be a nurse.

Was there a certain concept behind the album?

In the 1960s, two Philosophy scholars, Colli and Montinari, took up Nietzsche’s thinking. They revealed that parts of the later works had been added by the sister, the wife of a ferocious anti-Semite. Nazi thinking was tied to these statements which were not part of Nietzsche’s real thinking. I took up this approach and studied, for my thesis on ‘Eterno Ritorno’, the book “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” which fascinated me for its poetic language which is very adaptable to a musical text. I wrote the words, which have been changed many times, peering at Nietzsche’s text. When we made the album, however, I was not yet registered with the SIAE as a lyricist; a friend of mine, Mauro La Luce, who wrote the words for ‘Delirium’ then offered to sign our songs.

“Political bias played an important role in the evaluation of the record and the band.”

It’s a masterpiece!

It’s very difficult to explain our work. You know there are several perspectives to consider:

that of the author, that of the band and that of the audience.

The author writes following an inspiration, a model and proposes to the band. And here a mutation already takes place in the sense that the idea is adapted to the fact that the author is not a soloist. The musical and personal dynamics of the group test the original composition but I must say that in the case of ‘Zarathustra’ there were no major problems. In short, our group Museo Rosenbach was satisfied with its music, sound and the overall product it offered to the record company.

Ricordi’s management staff and our producer were our first audience. ‘Zarathustra’ intrigued them; the performance convinced them that it could also be groped because, at that time, the record companies were focusing on this musical genre.

However, the reaction from the general public was disappointing. Political bias played an important role in the evaluation of the record and the band. Despite a rich advertising promotion, the sales were not exciting and no one spoke of a “masterpiece”. Very few appreciations on the work; the bust of Mussolini and the shadow of Nietzsche were stronger than the music.

Years passed. ‘Zarathustra’ became one of the many attempts made by Italian groups in the early 1970s. In 1982 Museo Rosenbach had an unexpected stroke of luck. The Japanese record company King Records chose ‘Zarathustra’ to release the first CDs. In Japan the public did not consider the prejudice that had conditioned us in Italy. Museo Rosenbach and the record became an example of great Italian music. A few years later ‘Zarathustra’ was printed in Korea and began its international journey which fortunately continues.

It is considered a masterpiece and I am obviously proud of it; I like it because it represents a phase of my youthful life. In this record there is our enthusiasm. Nobody thought about the economic aspect. The goal was to record 33 rpm. I still find the rhythms and the cutting of the songs effective; our style is recognized in the alternation of soft and melodic passages with sections characterized by a more aggressive sound. I also consider the general message of the album still valid. However, I want to add that ‘Zarathustra”s success then conditioned the following musical production. Museo Rosenbach is the Zarathustra band; everything we did after that was valued against our first successful album. I am not complaining but the author who is in me suffers a little.

Did you do any shows or even tour?

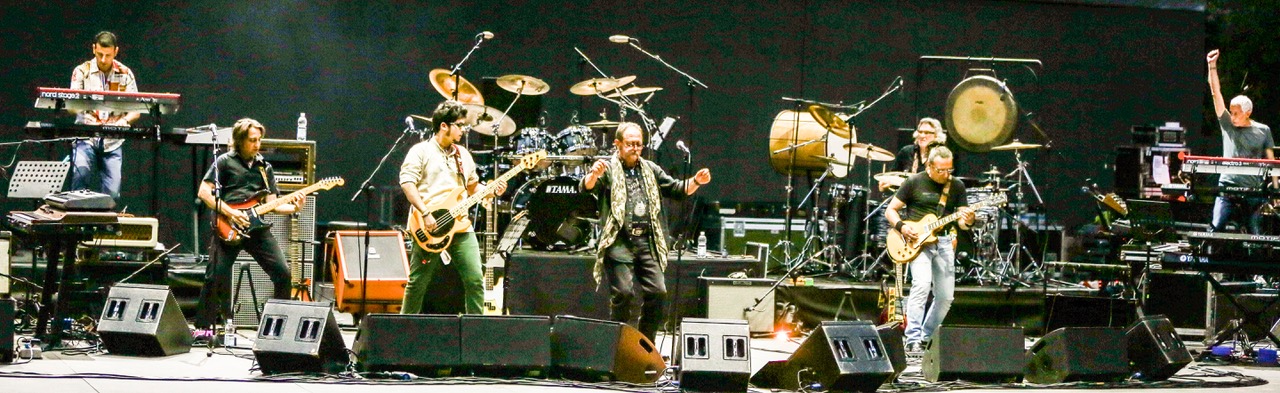

Museo Rosenbach didn’t play much. After the album was made, we did about ten concerts to promote it. In 2013 we played in Tokyo and Rome. In 2014 in Mexicali. In all three cases we were part of the prog festival.

What happened after the band stopped?

Golzi has entered commercial pop; Lupo continued with R&B covers; Merogno and Corradi have developed their professional careers outside of music; I remained in the balance: half a philosophy teacher and the other half I followed the path of the Matia Bazar, collaborating with them on some occasions.

‘Exit’, published in 2000, was the fruit of my musical half integrated by the friendship and competence of Marco Balbo, younger than us, but a skilled guitarist. With him and Golzi I considered the new material that had formed over the years in the creation of numerous auditions. We worked on it for a couple of years looking for other elements that would form a band capable of playing that material live. So, after about ten performances in local pubs without proposing ‘Zarathustra’ we believed it was worth producing a new release.

The inevitable comparisons with ‘Zarathustra’ were made and ‘Exit’ turned out to be an album not perfectly in line with progressive orthodoxy. I recognize that the songs on this album did not have the epic-symphonic structure of the previous one, because they wanted to tell a different, more intimate dimension. It is also true that the arrangements are more pop than prog, but this is due to a perhaps too long preparation phase that allowed us to go back to the arrangements several times with the result of curbing the creative momentum and innovative settings.

But I must add that, as an author, I do not consider ‘Exit’ structurally different from ‘Zarathustra’. The piece is always a small suite in which the parts are hard to repeat; the strictly musical inspiration seems to me the same. In short, ‘Exit’ was the son of his time as ‘Zarathustra’ was of his, beyond the labels of prog or pop.

Museo Rosenbach records when it has something it believes in. We have no conditioning of any kind. I loved this record because it was an opportunity to resume a discussion that I had begun and the very fact of continuing a speech is, in some way, a plan.

After ‘Exit’ we received a proposal from the Finnish prog magazine “Colossus” to participate in the “Kalevala Project”, that is, the experiment of making the epic poem Kalevala, a fundamental text of Nordic mythology, into music. The plan of the opera included the contribution of other progressive bands, not only Italian. We were interested in this and we found ourselves writing a small suite on an episode of this great story. Thus was born ‘Fiore di vendetta’, a song of about 7 minutes that has as its theme a very grim story, made up of violence and grudges. The environment is the mythical one and Museo Rosenbach has dealt with it by taking up the sound settings of ‘Zarathustra’.

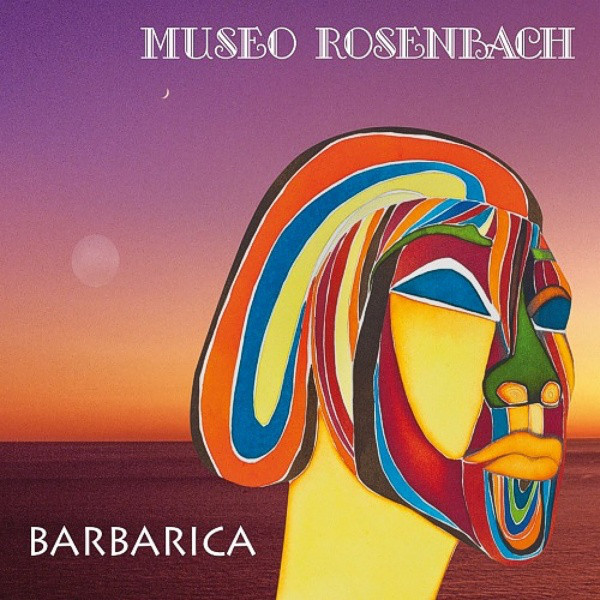

What can you tell me about ‘Zarathustra Live In Studio’ and ‘Barbarica’ from 2013?

The most interesting episode of the ‘Zarathustra Live In Studio’ was the moment we decided to do it! We were rehearsing the concert for Tokyo; in the lineup there were obviously all the songs ‘Zarathustra’ mixed with the songs of what was becoming the new album ‘Barbarica’. Unlike the Zarathustra era, we used to record our rehearsals to verify the sound and execution. We said to ourselves “Let’s set this phase of a work in progress…”. We have perfected some technical settings and in one day, or rather in an afternoon, we recorded.

Performing ‘Zarathustra’ live after many years I was struck by the writing of 1973 in which I found all my educational background… Gentle Giant, Jethro Tull, Genesis, Banco … then playing it with a keyboard I deepened passages that I then instinctively performed with another instrument. Andy Senis, the new bassist, is too good and I preferred to carve out a role of second keyboard and mellotron player. From a strictly technical point of view, making ‘Zarathustra’ with the current means available has brought about changes. The first difference concerns the use of the M400 mellotron; no more waning tapes that gave enormous problems especially in live shows… for the rest, new technologies have allowed a more accurate preparation work, a very easy exchange of samples… and a more controlled recording.

A few months after ‘Zarathustra Live In Studio’ the band has relaunched with a traditionally prog album: a well-defined, suggestive concept; a suite of about 14 minutes, articulated in the variability of rhythm and contents; 4 compositions that develop the topic from different points of view, thus remaining linked together like another ideal and long suite.

In fact, the album revolves around two themes: the first (‘Il respiro del Pianeta’) seems to be a reprise of the ecological discourse that the band had already tried to do with the ancient ‘Zarathustra’: man and Nature, their relationship full of impulses and contradictions. The second theme (the 4 songs) deals with the terrible nightmare of war: the clash between man and man which remains an apparently unavoidable flaw for the development of a true civilization. ‘Barbarica’ opens with a symphonic air; ‘Il respiro del Pianeta’ is in full Museo Rosenbach tradition and quickly transforms into a series of short cuts that disorient even the most willing listener. The second song, also totally unpublished, is ‘La coda del diavolo’ which brings the discourse on the horror of war. The division into two parts, the first serene and reflective, the second almost explosive in its fury, builds an emblematic song. Man can improve his relationship with nature if he knows how to change his attitude towards it, but the barbarism of hatred looms and suddenly destroys any search for peace and harmony.

The sounds reflect this message: soft and hypnotic to suggest the almost mystical reflection of man in search of himself, sharp and harsh in the moment of fracture in which harmony is torn apart by weapons. The closure in which Lupo summarizes this senseless fury is remarkable: his filtered voice comes as from a loudspeaker and colors the message with disturbing realism. The other three songs are not totally unpublished but it is clear that they are congenial to the concept that the band intended to propose. ‘Abandonati’ and ‘Il re del circus’ are reworkings of two pieces from ‘Exit’ as well as ‘Fiore di vendetta’ takes up a contribution that the Museo Rosenbach had given to the work produced by Musea Records in 2003: ‘Kalevala’. I believe that these songs are not a mere filler but fit into the discourse without any forcing.

In ‘Abandonati’ the guitars create an angry structure in which singing can paint a situation of silent pain, that of refugees who are desperately trying to reconstruct an elementary everyday life. Particularly effective is the initial part in which the use of English betrays the band’s intention to launch a globalized message that is an unavoidable warning to try to get out of barbarism. ‘Fiore di vendetta’ is another alternation of atmospheres and the music adheres to the story as if it wanted to visually express landscapes and events. The instruments evoke in the first part and are defined in their purely rock dimension in the final part.

‘Il re del circo’ comes with an excuse with a prog section in which the keyboards sometimes start to be intertwined to a nervous and full of adrenaline rush. This song well expresses the path that the band seemed to have taken in 2014: a mix between traditional prog and impact of metal that is useful for live performances. A particular note deserves the registration, full-bodied and punctual.

‘Zarathustra Live in Studio’, ‘Barbarica’ and ‘Live in Tokyo’ were realized under record label ‘Aereostella’.

“The most striking novelty of that period was, in my opinion, the construction of an album based on a concept.”

Italy had a lot of incredible progressive rock bands. Would you like to write a short essay (from your perspective) about the prog rock scene in Italy, back in the 70s?

First of all there was no prog. I heard about this label in the 80s. However, there were very important bands. I’m telling you about my experience. Being from Liguria and living near Sanremo I had the opportunity to listen to the New Trolls numerous times. They were the first point of reference. They came every week either to Club 64 in Sanremo or to the Kursaal in Bordighera. In this latest disco I had the opportunity to hear the Camel, Panna Fredda, the Fholks, a band from Rome that became Reale Accademia di Musica, The Trip, the Perigeo, Le Orme, The Primitives etc. But the group that struck me was Il Banco del Mutuo Soccorso. Their concerts were great; the voice of Francesco engaging. Only a few years ago I attended the performances of the PFM.

From about 1968 to 1975, the Italian musical environment was favorable to bands. It was played often. Locals easily hired bands and record companies had picked up on this ferment and encouraged it. Rock music festivals were organized or, as they said, New Trends.

The most striking novelty of that period was, in my opinion, the construction of an album based on a concept. Albums were no longer just a collection of songs. It was an articulated message that dealt with rather challenging issues: the evolution of man (Banco), the Bible (Il Reverse della Medaglia), the story of two profoundly different planets (Le Orme), Nietzsche’s thought. On these “conceptual” bases the way of composing also changed; the songs became “songs”, the percentage of only instrumental moments increased; the album covers finally reflected the concept becoming an essential element of the musical work.

This phase was later called “prog”. A linguistic observation: in the 1960s the groups were called “complex”. In the period we are considering this term appeared reductive and we began to talk about bands.

Defining a genre by creating a label is a risky undertaking that leads to grueling debates. Prog has existed since the late 1970s, before it was psychedelic rock\decadent rock. Progressive includes hard rock, folk and jazz; perhaps prog can be defined precisely as a “tendency” to amalgamating genres; it is a flow that collects contributions rich in nuances. There has not been a well-defined nucleus that has evolved; several tributaries have given birth to a river that is affected by the seasons. It does not matter if it is rich or poor in water; the important thing is that it flows.

Would you like to comment on your playing technique? Give us some insights on developing your technique.

As I told you I was born a pianist but I remained an amateur on piano. This training however allowed me to develop my composition techniques. At the base there is a sequence of chords on which the theme is developed. I then assemble the sequences trying to make them organic and functional to a musical environment. In the 1970s I proposed these sequences to the group. Their execution led us to the “bridges” or further development. I never work starting from a text. I am only interested in the singer as regards the tonality and obviously I am ready to modify the original one. The 1970s Museo Rosenbach never recorded the compositional progress that remained in the collective memory. When the song was ready for singing, an English-like language entered the scene. The following phase was the most demanding: transporting the English-like, full of trunks and therefore suitable for rock, into the Italian language. As a bassist, my contact was naturally the drummer Giancarlo Golzi. I played with him from adolescence until 2015 when he suddenly passed away. Our understanding was perfect. I’ve always played bass instinctively, certainly unorthodox. Golzi was keeping me at bay.

What currently occupies your life?

After the death of Giancarlo Golzi, Museo Rosenbach closed its doors permanently. I continue to play the piano and compose songs that do not have the opportunity to be published. It’s a bit like going back to the early 70s when playing music. I finished my teaching career and I work in the countryside helping my wife Manuela with her thornless succulent plants.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you for your interest and for the opportunity to introduce your readers to the background of the Museo Rosenbach. It was for me an opportunity for artistic reflection on my entire career. I would like to advise those who want to deepen our music to listen to ‘Live in Tokyo’. In those two discs there are our whole world and the expressive power of the live Museo Rosenbach. You asked me to be thorough. I hope I have satisfied you. Alberto Moreno

Klemen Breznikar

Museo Rosenbach Facebook

great