Frans de Waard | Interview

Frans de Waard has been producing experimental music since the early 80s.

From the beginning with Kapotte Muziek to Beequeen (with Freek Kinkelaar), Goem (with Roel Meelkop and Peter Duimelinks, both of whom are also a member of Kapotte Muziek), Zebra (with Roel Meelkop) and solo projects under the moniker Freiband and Shifts, as well as under his own name. He has worked for Staalplaat (1992-2003) and since 1986 as a reviewer for his own publication Vital, now Vital Weekly, an online music magazine, which has been the online source for underground music since 1995.

“You are born, you die and in between, you want to stay away from boredom”

How did you get first interested in music? What kind of music did you listen to as a young teenager?

Frans de Waard: Music was always part of our household. My father was heavily into classical music from the 19th century and particularly fond of Antonín Dvořák, best known for his Symphony No. 9 (he even named my older brother after him and wrote a book on the man in the late 80s). He played that on an average Sunday afternoon with quite some volume. He didn’t like much other music, so when my brother and I started listening to pop music, or watching it on TV, he always said: “That’s a passing thing, nobody will remember this in 100 years”, as if that is of some relevance. The first band I liked was Abba, seeing them win Eurovision, as it was the first time I was allowed to stay up late. I still love Abba. The first 7″ I bought was ‘Egyptian Reggae’ by Jonathan Richman and the second was Jeff Wayne’s ‘Eve Of The War’, so early I favoured instrumental music. I think I said I liked Paul McCartney, but don’t remember having a lot of his records, although I was a paid-up member of the Dutch fan club. One of the first LPs I bought was ‘Replicas’ by Tubeway Army, still, one I like very much.

Where and when did you grow up? Did the local scene have any impact on your music taste?

I grew up in a suburb of Nijmegen, sort of mix between low and middle class, back then. These days lower class, I think. This was in the early ’70s and I quickly left punk for what it was, although I collected Dutch punk 7″ quite a bit, as soon as I discovered cassettes, I went for experimental music. There was no scene for that sort of thing in Nijmegen, or at least not one that for a 15-year was interesting in terms of a peer group. Mekanik Kommando was from here, the best known “Ultra” band, but they were at least 10 years older. It took me until 2012 before I really started to know them, and Peter van Vliet, their singer/bassist, produced the final Beequeen CD. I guess to him I was the noise kid from the suburb and he came across as a sort of a hippie. We were both wrong.

When did you decide that you wanted to start working and performing your own music?

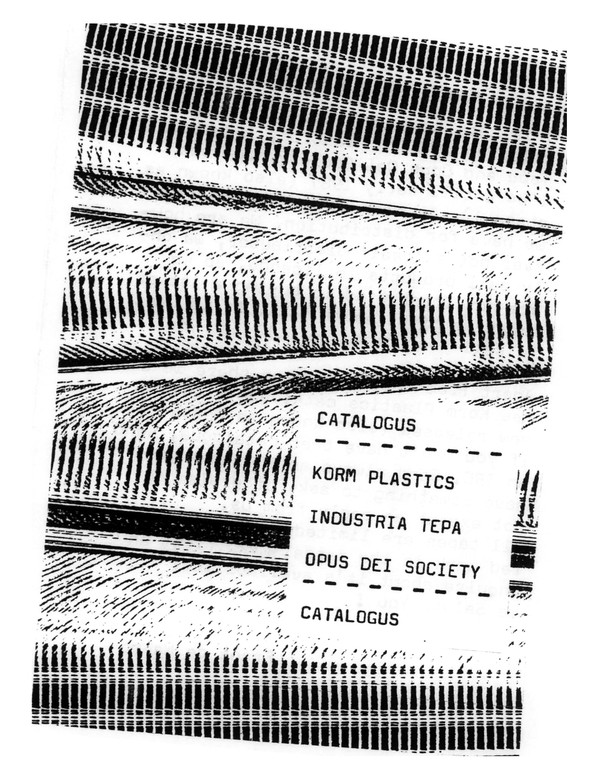

I did briefly some experimental music, but I had no real equipment, so I stopped and only started again in October 1984, when I started Korm Plastics and Kapotte Muziek at the same time. I compiled a cassette with Dutch industrial music and filled up the one-minute left at the end of that tape (‘Katacombe 3’) as Kapotte Muziek. That’s how it started.

Can you elaborate the formation of the Kapotte Muziek?

Because I was training to be a teacher I had access to cheap xeroxes and cheap blank tapes and a classmate of mine asked me what I was doing buying blank tapes every day, doing tons of xeroxes, so I explained that I had a label and a band. His name was Christian Nijs, and was interested and lived in a house with everybody playing instruments and anyone could go in a room and take one to play, so Christian made recordings with these and gave me these recordings to work on. That became the first version of Kapotte Muziek, until early 1987, when we did our second concert (first in public) at V2 in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, along with THU20 and Odal, and we spend three days preparing (I have no idea why anymore; it felt like a holiday) and Christian told me this was the last he did with me because he wanted to learn to play the guitar. He did learn, and I saw a concert of his rock group and lost contact until 1999. Then I saw him at the local supermarket. We agreed to meet again, didn’t and in 2006 I heard he took his own life in 2002.

Was there a certain aspect/concept you were trying to achieve?

Not really. I have no message, no meaning, no bigger idea. Just as I stand in life, really. Also there I can’t see much meaning or idea. You are born, you die and in between, you want to stay away from boredom. That’s why I do music and the other things I do.

Not really. I have no message, no meaning, no bigger idea. Just as I stand in life, really. Also there I can’t see much meaning or idea. You are born, you die and in between you want to stay from boredom. That’s why I do music and the other things I do.

You released a ton of records and tapes. What was the typical process like to record and release the music?

There is no “the band” in my work. I use(d) lots of names, each with a specific idea. An album by Beequeen took years to record. A Modelbau cassette is typically the result of a few nights one month and selecting the best moments. A Freiband release these days is the result of “action composing”: generating a few larger blocks of sound and do a mix, without looking too much at details, but making final edits once the mix is down to 2 tracks. Songs by my new project Ruisch are also the result of writing over a longer period. It varies.

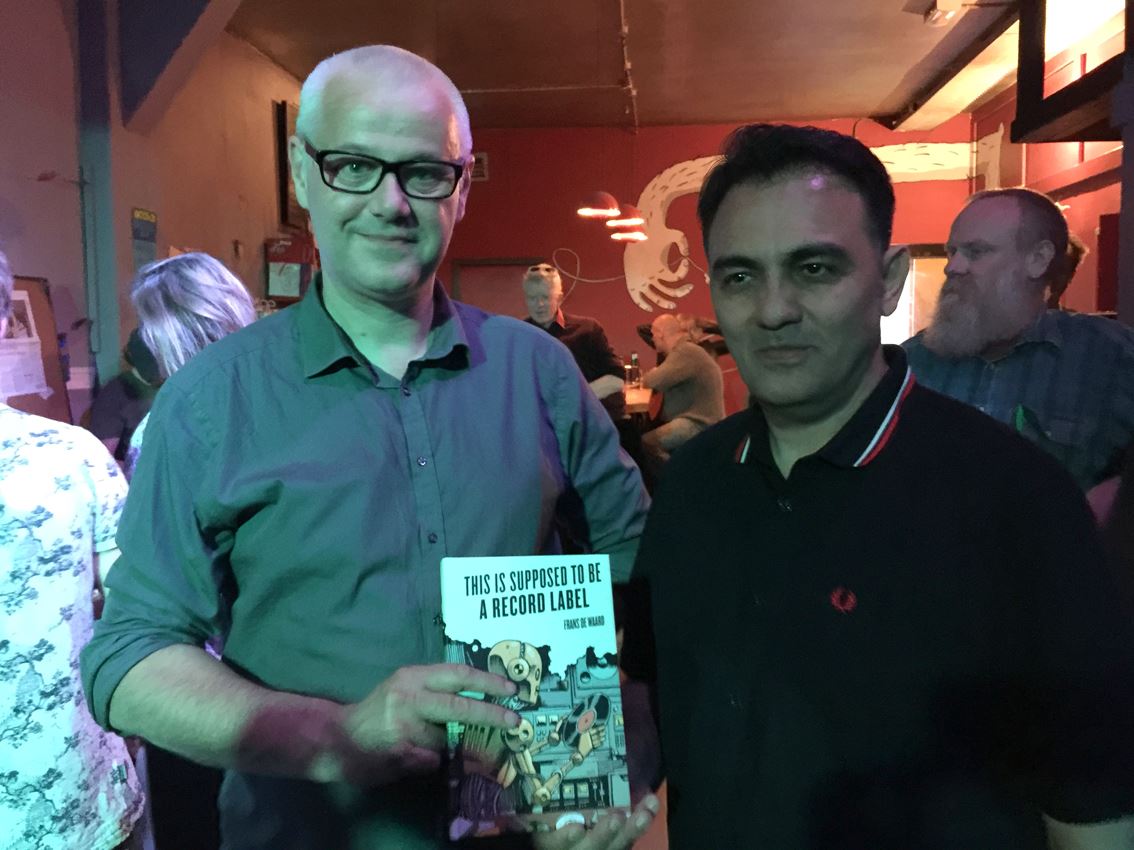

What’s the story behind forming Korm Plastics label? What was the main reason behind it?

It is quicker to quote my book for this question (‘This Is Suppose To Be A Record Label’): The name Korm Plastics doesn’t have any deeper meaning. I’ve always hoped some foreign language expert might tell me if ‘Korm’ means anything (I was told in 2008 that it means ‘food’ in Russian). I didn’t want my label to be called ‘Records & Tapes’, as I had vague intentions of becoming a “multimedia” releaser, and when the time came, of expanding into books, videos, posters and god knows what else. So “Plastics” it would be, but it was never meant as a comment on Western consumerism. I probably thought of myself as an anarchist back then, of the Max Stirner/individual variety, but I was never that political. I do know, however, that the ‘plastics’ bit in ‘Korm Plastics’ inspired Illusion Of Safety’s Kurt Greisch when he named his own label “Perdition Plastics”. (page 11, 12)

There is no such thing as Korm Plastics Records!

In the late 80s you formed Beequeen with Freek Kinkelaar. How did that come about?

Freek contacted me because I published a booklet with the discography of The Legendary Pink Dots. I tried brushing him off, as is my usual strategy, but it turned out he was also in Nijmegen, not too far from where I lived, and we met up and it turns out he did “experimental” music as well. He played the guitar and I invited him to be part of a strange event in which five people made music on four locations in a building, and they could only hear the others through a monitor. The audience had to bring a radio since there was no other amplification. Not a big success musically (and not many brought a radio) but somehow Edward Ka-Spel of the Pink Dots, also living in Nijmegen and connected to Freek, asked him to do a support act and so Freek asked me. Again, not a big winner for this first concert but as we were students with summertime on our hands we recorded a bunch of material in my parent’s attic.

Then there’s your own project, Goem. Goem a Russian term for shops whose products were available only to Communist Party members. It’s basically you exploring a Student Stimulator. What can you say about this special device and how did you get the idea to start a project around it?

Roel Meelkop found this device in a thrift store and had no clue what it was for. We still don’t know! It gave pulses, short and long ones and you could change the intensity. He used it a couple of times in Kapotte Muziek concerts, became bored with it, and gave it to me. I made the first Goem tracks solo, recording pulses on one track, copy that track with sound effects to the 2nd, 3rd and 4th track of my machine, and enjoyed the repetition. When we drove to Amsterdam to record for VPRO our Kapotte Muziek ‘Mort Aux Vaches’ CD, I played these pieces for my then-wife and Roel and Peter from Kapotte Muziek. Halfway through the first piece, the three of them screamed: “take this bloody irritating ticking shit of, Frans”. But a few days later I got a fax from Roel, saying: “I thought about your music with clicks, and maybe we can put it through a synthesizer, it might be interesting”. Then we recorded some pieces. Half the first CD ‘Stud Stim’ are still my first solo pieces, the other half is Roel and me.

You were joined by Roel Meelkop for the album ‘Stud Stim’ and a bit later by Peter Duimelinks.

I was working for Staalplaat at the time and every now and then people phoned to see if our artists were available for a concert and there was some interest for Rapoon in Barcelona, but he couldn’t do it, so, cocky as I was, I said, “I have something new with a CD just out by Raster Music (a label nobody heard of at that time; Goem was the first foreign act with a solo CD on that label. Little known fact. I never heard from them again in twenty years), so why not have us?” I send them an mp3, which took at that time 5 hours via email, and then Roel and I were faced with the task of a Goem concert. Peter, we knew from THU20 and Kapotte Muziek, and he fancied a trip to Barcelona as well, so we decided that Goem should be a trio. In the first few concerts we would switch roles during a concert, each playing synths or mixing, but in the end, Peter was the mixer, because he controlled his nerves better than Roel or me. I guess.

Then there’s a duo Zèbra with Roel Meelkop.

On the road, in the car, there was always talk about silly new things we wanted to do, and one of the things Roel and I wanted was a laptop punk band. Play 10-minute sets with lots of samples from pop music. And we would call it Wibra. Goem being this Russian store with expensive stuff, Wibra this Dutch store for really cheap clothes. My wife suggested Zebra, made out of the words “wibra” and “zeeman”, another cheap brand, as that’s how kids well called in school that dressed cheap (she was a teacher in one of the poorest parts of The Hague at that time). We made it Zèbra, to be different. Of course, later on, some bearded rock band from the USA say “we have the entertainment rights to the word Zebra, so would you please change the name?”. We tried arguing we were Zèbra, so entirely something different, but to no avail. So, we used the non-used letters of “zeeman” and “wibra”, and we called ourselves Wieman. There is actually a Dutch piano player Henk Wieman. He has not contacted us yet. In any case, should Wieman still exist! We don’t know what the status is, although there is an upcoming track on a 3″ compilation with Casio instruments. It has twenty songs that are by twenty different versions of Frans. A bit megalomaniac, if it was my idea. It isn’t.

What would you say is the main difference between your work with other artists and your solo projects, like Freiband, Shifts … ?

Every project, solo or with other people, is its own thing. In each of my solo projects, each name is a different approach. Freiband is all computer music, Shifts was (!) all guitar music, Modelbau is very open but involves lots of cassettes, cheap stuff, radio and effects, QST is ambient house music, Quest is all ambient but not much rhythm, Ruisch is my latest more dub oriented project.

With some people I have improvisation music projects such as Jos Smolders (in THU20 and WaSm) and Wouter Jaspers (Ezdanitoff). With Scott Foust, from Idea Fire Company, I have The Tobacconists, and we more or less plan our pieces; I wish we would do something else again! Something similar I have with Sindre Bjerga, as Tech Riders. We also play pieces, but of course, they are flexible. And there is stuff that is one-off such as my various projects with Steven Wilson. I propose a concept and then we do it, whenever he has time to work on it, which, as the big-time rock artist he is, is rare. We may do something again this year. Also, with Howard Stelzer I work together for more than twenty-five years now. I work with lots of people, Mathijs Kouw, Asmus Tietchens and Miguel Garcia, to mention a few recent ones (I hope I have not offended anyone by not mentioning them)

You also worked for more than a decade for legendary Staalplaat. How did that come about and what was your position there?

This question can be re-phrased as: can you quickly summarize 228 pages of your book ‘This Is Suppose To Be A Record Label’? That is about my 11 years working at Staalplaat. They hired me to buy and sell records, maintain contact with labels and get a database in order. The latter I had no idea how to do. I ended up with an unofficial capacity of a know-it-all, running much of the day to day business, and not doing (repeat: NOT) the A&R side of the label.

What’s the story behind your own publication Vital… you managed to produce astounding 1000th + issues. How do you do it?

I just work very hard, every day and all day. Also, not having a proper job helps. I sell records from myself and others on Discogs to pay the bills. The music I generally do in the evening. That’s it really. And as a catholic boy in The Netherlands, I have a very protestant work ethic!

First Vital was a paper fanzine, two folded A4 sheets. I did 44 issues between 1986 and 1995. Interview, reviews, a bit about a label and later on discussion stuff about composing, plagiarism, noise and such. When Staalplaat connected to the internet in 1995, I had this idea of doing a weekly review newsletter. I would not have guessed I’d still be doing this in 2021.

“Middle of the road guy with an odd taste in music, books, films”

In 1991 you released the ‘Anti White Bastards’ tape. Maybe you can share a few words about it? I guess it was released as an answer to some right-wing tendencies in the noise scene?

Yes, indeed, against the AWB label from Chicago and their “band” Terre Blanche in particular. Of course, many early industrial noise groups and projects toyed with similar images and it wasn’t always clear if it was a comment or genuine right-wing bullshit, but these guys were the real thing, as far as we (PBK and myself) were concerned. Now, thirty years later, I couldn’t reproduce the evidence we had. I was more part of that scene and exchange of tapes and fanzines, so I guess I had more of an opinion about such things. In the current landscape, I find it all the more confusing. John Lydon supporting Trump, and I guess because he thinks “Trump is the real punk”, or so (have you ever been cheated, John?), all these conspiracy idiots (“yeah man, I can read so I found the truth2 or, worse, “I have been red-pilled”), the right-wing is a business model; click my website and make me rich. In the old days, things were easier across the divide, left and right (and while I love to say I was an anarchist in my early days, I would not describe myself as such anymore; I am not really left-wing, and certainly, I hope, not right-wing. I am just a very middle of the road guy with an odd taste in music, books, films and historical matters, and I also love to read lots of conspiracy stuff; I need a good laugh every day). I regret working with some homophobic shit from Russia some years ago. When he expressed his views on Facebook, I engaged in a private conversation, which was all about the perverted West. I ended that particular “friendship”. He calls me a “liberal fascist”, which is not a nice thing, but I wear it with pride.

How about Bake Records and Plinkity Plonk Records?

Bake Records I set up in 1999 when I bought a CD burner, and immediately I saw the possibilities of having a cassette label, but then on CD-R. A friendly young man that hung around at Staalplaat, Roger NBH, volunteered to do the covers and we gradually built a fine catalogue. Of course, it no longer exists and waits to be on Bandcamp. One day! Plinkity Plonk was Freek and me on a label, even if I paid the bills. In the end, we did 33 releases, which seemed like the proper number to end this (45 or 78 would have worked as well), and the last one is a LP/CD by Andre de Saint-Obin, which is an old tape, from 1985, which Freek and I loved very much, and it took years to find the guy and do the LP. It didn’t sell well, copies disappeared in the USA due to the bankruptcy of Aquarius Records and it was the last CD or LP I released. My heart is no longer in being a record label.

How do you remember your tour of Japan with Pan Sonic?

At one point Goem was at a dead end and we had no idea how to continue unless we wanted to repeat ourselves. We didn’t. We decided that each of us would try our hand at a solo album, developing our own techniques and then come back and see how we could integrate what we learned. I was the first one done and Roel second; Peter never did anything, as far as I know. I enjoyed my solo album and found a label, Atak, in Japan willing to release it. I remarked: “I’d be happy to promote the album through concerts”, to which they replied that there was not much interest. I always try to play that card! Much to my surprise, I got an e-mail six months later, saying “can you be in Japan in February and play with us and Pan Sonic, at a few concerts? We buy you a plane and train ticket, hotels et cetera”. Of course, I wanted! Being a big fan of Pan Sonic and having met Ilpo and Mika in Staalplaat a few times. I phoned my former boss at Staalplaat, who knew them even better and asked him how I should behave around such quiet men and he gave me some fine pointers. Mika was in a teetotal phase and very quiet, although we spend a lovely evening smoking big cigars and him talking about Cuba. With Ilpo I spend over 200 euros on a handful of drinks in the most expensive area in Tokyo; we didn’t know. The final night, at Unit, was great. A rocking full house and filmed for posterity.

You are performing under different monikers. What is the reason for different names? Maybe different kinds of recorded material?

I like to think that every name has a specific sound and that it is different from another name, hence a new one. Working procedures vary per project. Modelbau for instance is all improvised. I switch on the machines that are permanently on my backroom desk these days (writing such as these words happen at the front desk) and start looking for sounds. Once there is a dialogue I start recording. In recent months I try to record something every day for about 20 to 30 minutes, to see how I can do that. Freiband is all computer processing of sound and I stick very long, processed files together and find a dialogue there, but without listening to all the small details. I render a mix and then work inside that, creating fades, edits and such. I have a bunch of projects that involve various apps for the iPad, such as QST and Ruisch (and to a lesser extent Quest, the ambient sister of QST, which is more ambient house), for which I sit down with headphones and take a long time to compose a piece. Other solo projects, such as Shifts or Captain Black are closed, I think. I ran out of ideas there, I guess.

I would be delighted if you can take some time and reflect on underground tape culture in the Netherlands and abroad. What was it like to be part of the scene?

I must admit I never felt part of any scene. I was living with my parents until I started working for Staalplaat in 1992 and the scene, I think, were just some friends. Sjak from Midas/Antenne, the V2 people, my friend Christian in Kapotte Muziek, THU20 (Jos Smolders, Peter Duimelinks, Roel Meelkop) and I was corresponding a lot with people, Peter Zincken from Odal, for instance. But is that a scene? I am not sure. I felt less connected to people from the squat scene. I don’t know why; maybe because I didn’t squat?

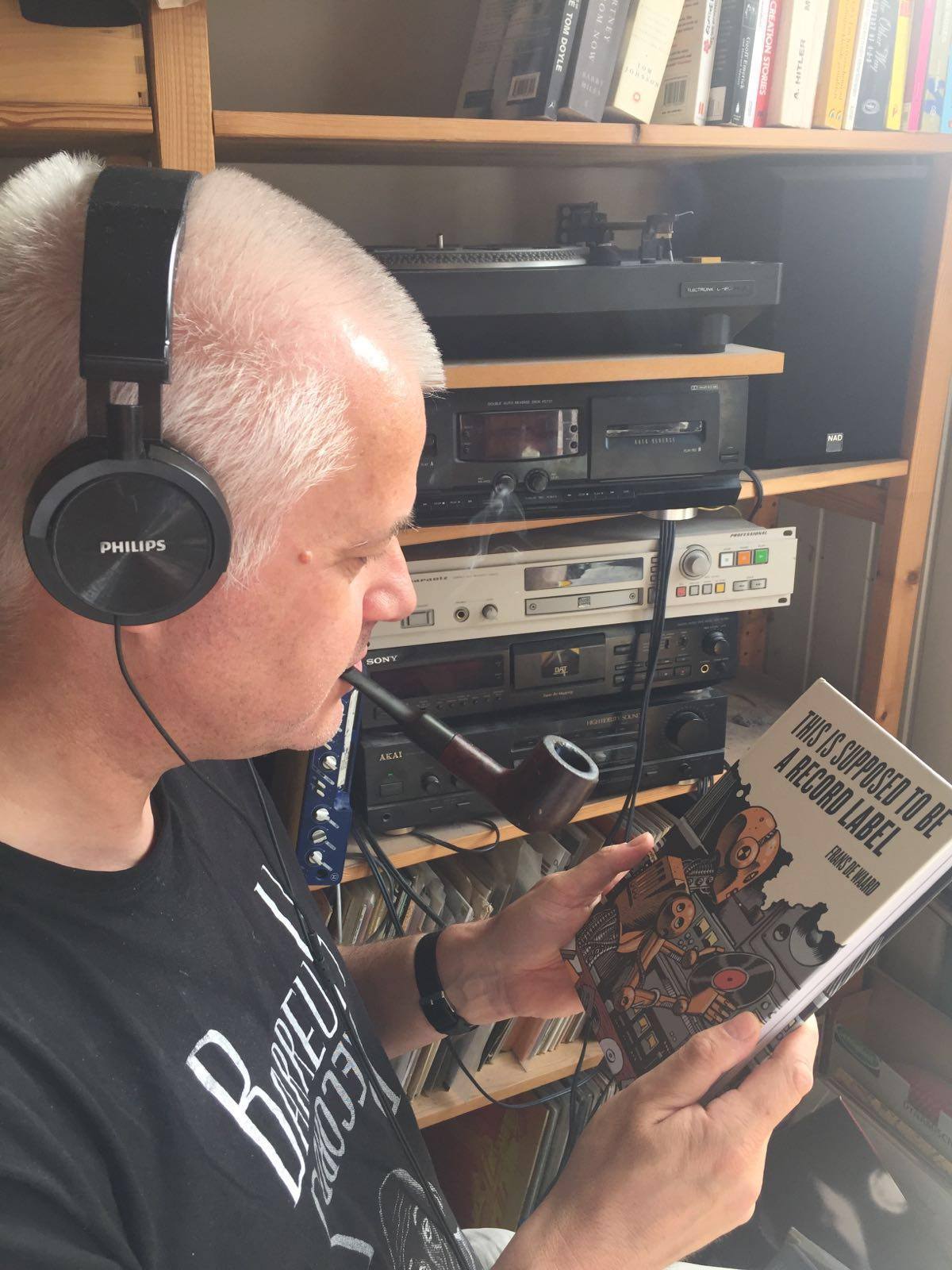

Do you still go out and dig through piles of records these days? What are some of the latest finds?

I review a lot of music for Vital Weekly, so yes, I have at various times a lot of records on my desk. I am not, however, even remotely interested in rare, obscure records and never buy any record. I do trawl the internet for interesting stuff to hear, which I don’t have to review. Old dub records, post-punk and electronic music (The Berlin School sort of thing). I have my soft spots for those.

Is there an album that has profoundly affected you more than others?

Not really, I think. I like lots of records, too many to mention, some I regard classic! The first 2 LPs by Dome, ‘Heartbeat’ by Chris & Cosey, everything by Five Or Six) but affected? I don’t know…

It’s absolutely impossible to cover your discography. Would it be possible for you to choose a few collaborations that still warm your heart?

Obviously, I’d say the few I did with Steven Wilson, including performing with him. I was very surprised that he would be at all interested in the non-musician that I am, but also that he knows so much about it. Also the radiophonic opera ‘Smoking Is Green’ with The Tobacconists I still enjoy. Wieman played a great concert in Brussels, promoting an LP we did for ini.itu. Goem at Sonar. My concert with Martijn Comes in Amsterdam in 2019. The last Beequeen concert when we were a quartet.

What currently occupies your life?

The same thing that occupies me since I left Staalplaat in 2003. Reviewing music and selling records. I added publishing books to that. In the evening I record a bit of music; I try to do that as much as possible. Not necessarily so I can release many records, but to push the envelope, repeat ideas until something good arrives. Like a band in rehearsal, but then, just me at home. Sometimes I radically change the set-up and take it from there. The picture shows the current, messy set-up.

The book publishing business is something I enjoy a lot. I have the same enthusiasm for it as when I started with cassettes. In the works is a novel by Adam Morris, a book on Dutch punk (1976-1982), a book with letters by John Balance, a book on the first Hafler Trio LP (another classic, one that affected me a lot), a smaller book about Broken Flag, a collection of Nul Nul (the fanzine I did before Vital), a collection of Dutch Fanzine Boh, a book about Jim Xentos/The Homosexuals. Maybe I forgot one or two!

How are you coping with the current pandemic and what are your predictions for the future? Do you think the music industry will adapt to it?

I gave up predicting the future some time ago, but I foresaw that coming. I can predict the past if that is of any help. For me, nothing changed. I do what I always do. I always have very few gigs, so nothing I miss there. The occasional trip to the pub or restaurant is missed. Otherwise, it all goes by me, I must say. However, the whole “stay safe, stay healthy” I was fed up quite early on. I wish everybody much health without saying, and if not, I wouldn’t say. Didn’t people wish other people “stay healthy” when it was not necessary? And why do all these avant-garde people use the same worn-out language? I don’t know. I got my vaccine shots, I predict (yes) we’ll get these shots every year. I also get those against the flu. I am a very middle of the road kind of a guy.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

The downside of occupying myself with reviewing music that I listen closely to a lot of stuff, but I also easily forget what I heard. There is nothing that sticks out that comes to mind. Also, I am not very good at such questions, even when I can think about them for a long time.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

Confusion will be my epitaph.

My epitaph: I gave up smoking and see me now.

Klemen Breznikar

Frans de Waard Official Website / Facebook / Twitter /