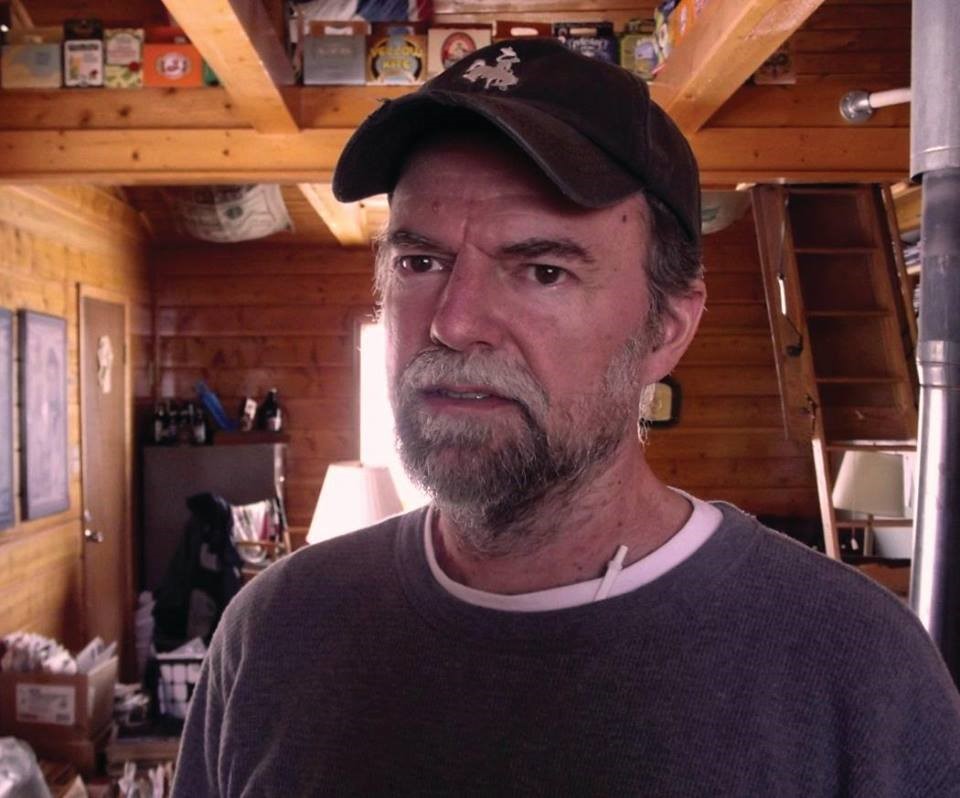

Joe Carducci | Interview | “My approach to things was to be open to any outlet”

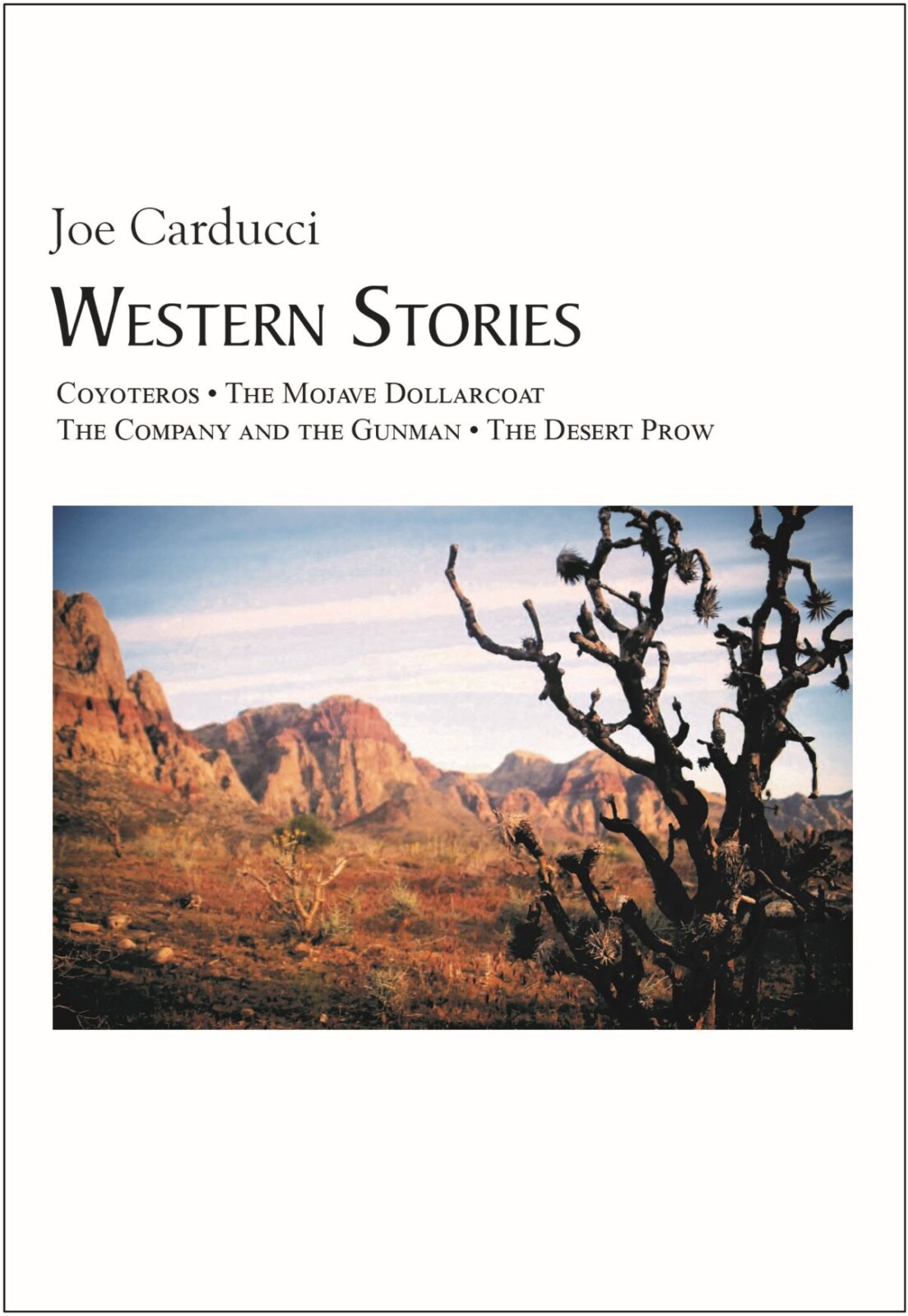

Joe Carducci, the author of critically acclaimed ‘Rock And The Pop Narcotic’, recently released ‘Western Stories’ – his second collection of screenplays.

With his previous book, ‘Stone Male – Requiem For The Living Picture’, Joe Carducci traced the historical evolution of working class-focused action cinema from the movies he liked in the 1970s back through the decades to their sources in early cinema before Hollywood and for comparison those before the Sovietization of Russian cinema. After seeing so many films and writing out what they cumulatively reveal, Joe gained confidence and perspective writing his next work: “I know what I’m doing now as a writer so what’s left is to produce as much work as possible in the time left.”

The stories that comprise ‘Western Stories’ became easier to write having just explored the construction of the genre and using historical settings to suggest the stories:

The Company and the Gunman – The Overland Stagecoach Co. and Jack Slade, the first of the screenplays written is “a complex epic that ranges coast-to-coast in the run-up to the Civil War” – as author describes it.

The Mojave Dollarcoat, was next and is the author’s attempt to scale down a story to the collision of Mojave and the Americans crowding them, exploring the misunderstandings with the army scout Tuhudda caught in the middle.

Coyoteros, scales down further to Boetticher/Hellman territory in its story of how young males of both the Natives and the Anglos can jeopardize the peace in the Arizona Territory.

‘Western Stories’ was released on 28th of September via Redoubt Press.

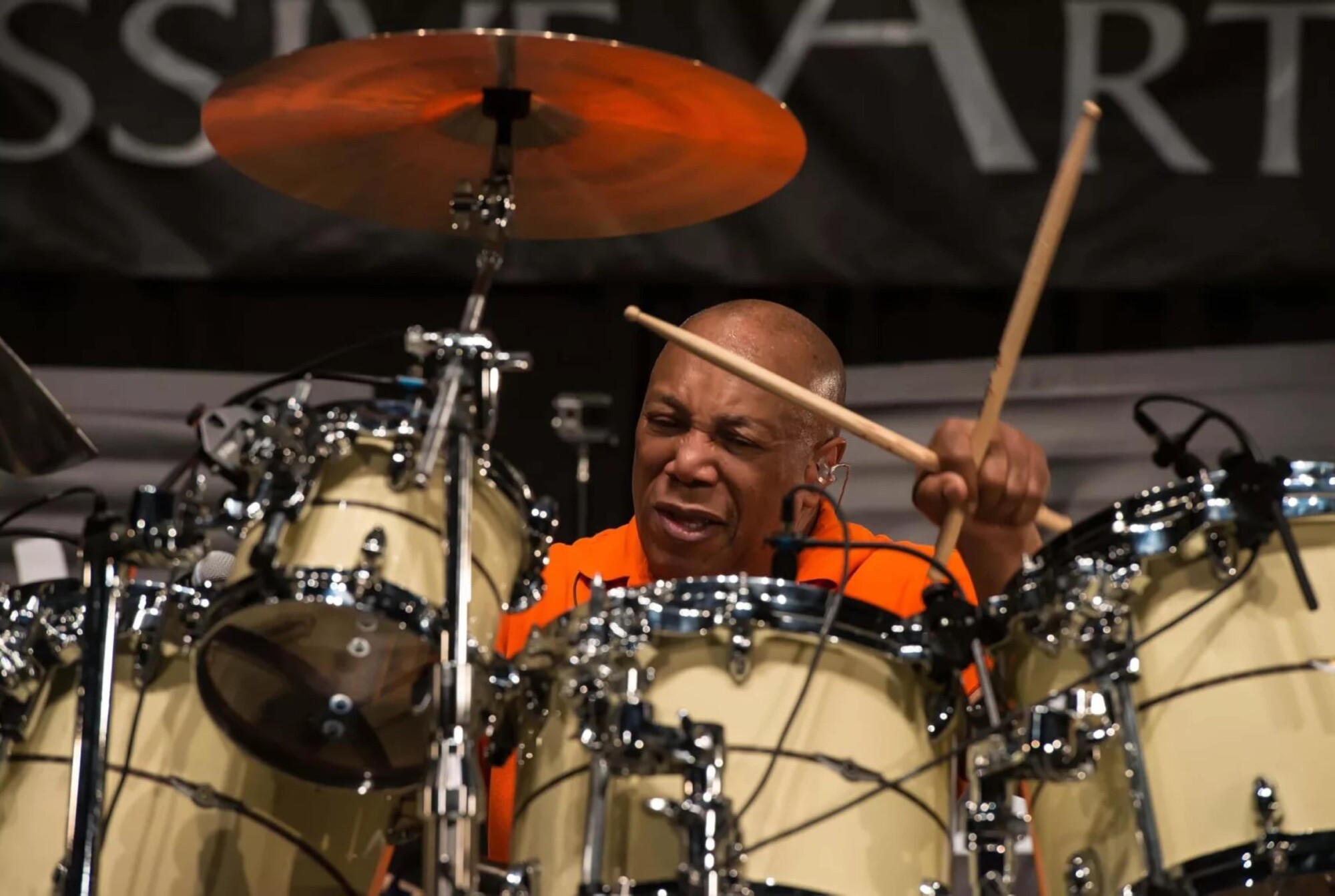

Joe Carducci was born in Merced, California in 1955. He grew up in Naperville, Illinois, attended the University of Denver for a year and a half before moving to Hollywood in 1976 to pursue screen-writing. While working at Portland’s Renaissance record-store, Carducci co-founded Systematic Record Distribution in 1978, moved it to Berkeley at the end of 1979 and was involved in the Thermidorand Optional Music record labels. He moved back to Los Angeles in the fall of 1981 to work with Black Flag’s label, SST Records, until early 1986. From 1981 to 1986, Joe Carducci was a partner in SST Records with Greg Ginn, Chuck Dukowski, and Mugger. Joe co-produced releases by Saint Vitus and others, contributed lyrics for Minutemen and took a principal role in the establishment of their careers and others such as Black Flag, Meat Puppets, Saccharine Trust, and Hüsker Dü.

Your new book – ‘Western Stories’ is coming out at the end of this month. Are you excited about it?

Joe Carducci: Yes, it was nice to look up and find that I had written four good Westerns which would make a nice collection. I had some good photographs taken while hiking in Wyoming and Nevada to illustrate those two settings but I had to use a couple shots by my brother-in-law to illustrate the Arizona setting of the other two.

What inspired you to write ‘Western Stories’?

Just getting an idea for a story and a character and a setting that all pan out. It takes a few months so you don’t want to invest the time on something that doesn’t have the right potential. But its all guesswork since you don’t usually know how a story will end when you start it.

How long did it take to complete this project, from conception to publication?

I started reading research for ‘The Company and the Gunman’ right after finishing my film book, ‘Stone Male’, in early 2016, so that’s five-and-a-half years to write the four stories and get the book printed.

Where does your love for writing screenplays come from? What are some of the most important writers that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ?

I think the first films I liked were the thirties comedies by the Three Stooges and Laurel & Hardy that WGN would show for kids programming. They even had a show where a guy dressed up like an old projectionist in the theater after closing who would take out some of his favorite old silent comedies and show them. When I later got more seriously into films in high school I would try to write sight-gags when I was stuck in a boring class so that probably makes Clyde Bruckman and Elwood Ullman my earliest screenwriting influences. Later I came to appreciate the screenwriting of Burt Kennedy, Borden Chase, James Edward Grant, Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur, Rowland Brown, Elmore Leonard, Alan Sharp, and the guys who wrote for John Ford over the years: Dudley Nichols, Frank Nugent, James Warner Bellah. Writers don’t control anything in Hollywood but they can come up with characters whose behavior is interesting and come up with some dialogue lines that give the actors something to work with and maybe the structure of the drama will survive the production of it. Maybe not.

In your previous book, ‘Stone Male – Requiem For The Living Picture’, you traced the historical evolution of working class-focused action cinema from the movies you liked in the 1970s. Can you elaborate on the concept behind it?

I was in high school in the early 1970s when film critics seemed to hate some of my favorite actors, Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson in particular, because they weren’t considered to be acting and were thought to be unable to act. These critics considered theatrical training and the new realism of intense kitchen sink off Broadway acting to be real acting. I kind of built on the idea that there was something like an “unschool” of non-acting that included people who had been stuntmen (Ben Johnson, Richard Farnsworth) or athletes (Jim Brown, Buster Crabbe), or soldiers (Audie Murphy, Neville Brand) that when they were good had some level of authentic representation that was superior to acting as taught in theatrical training. There were also stars who became actors because of their looks and some of these came to be good in their unique way too such as John Wayne or Robert Taylor. This is acting for the camera. There was a story about Laurence Olivier’s first tour of 20th Century-Fox as the celebrated best Shakespearean actor on the London stage. He was taken to watch a shoot of a scene in a production and he said he was still waiting to see Joel McCrea act when the director yelled “Cut” and it was over. Then he later saw the take when they ran the dailies and was impressed at the intimacy and effectiveness of what the camera had picked up which had seemed to be nothing on the set.

What about ‘Rock and the Pop Narcotic’?

I was in the independent label and distribution business between 1978 and 1986 and I thought if I didn’t write these underground bands with their self-released records into the history of rock and roll nobody else would do it. At Systematic Record Distribution I received samples of almost everything released independently in the US and UK and these included many important bands that Rolling Stone mag and the Manhattan publishing industry had zero interest in. After writing the book itself, trying to nail down aesthetic questions and answers I saw that in order to communicate what the implications were I’d have to rewrite an historical narrative of the music, so actually it seems to me that it is two books in one. I put out 2,000 copies of R&TPN on Redoubt, then Henry Rollins put out 3,000 copies of the revised edition on 2.13.61, and then I’ve printed another 3,000 copies of that on Redoubt Press again.

“During the the early 80s when we seemed to have one crisis per week”

Would you like to tell us about collaboration with Raymond Pettibon?

While working with Black Flag we got to know Greg Ginn’s family well, too well if you asked them they might say. During the the early 80s when we seemed to have one crisis per week with the LAPD, or some label, promoter, or distributor, or just no cash flow or reliable vehicle the Ginns were always there to help with their son’s trip. Raymond was working on his art every day but he often went to the gigs with us or I’d go to movies or Angels or Dodgers or Lakers or Kings games with him. In addition to having his art on flyers and album covers SST sold the booklets he printed up. I later started my video releasing company, Provisional, by distributing the four video-films he made in the late 1980s. Raymond was one of the incredible people around the Los Angeles punk scene generally, and at SST specifically.

What inspired the 8-track cartridge documentary ‘So Wrong They’re Right’?

We were just looking for interesting movies to release on videotape at Provisional, and although like Pettibon, Russ Forster had self-released the movie on vhs tape, we thought we could print up a standard videobox and sneak it out into the video rental business and sell a few more to collectors. Although we got alot of press on Russ’ doc, sales at Provisional were decreasing because the more open buying patterns of mom & pop videostores was giving way to the Hollywood blockbuster obsessions of the big chains. I may write a screenplay about the death of the videostore business as it was full of interesting, funny, and sad characters.

Are you planning to work on something similar to the underground New York drama, ‘What About Me’ featuring Johnny Thunders, Richard Hell, Dee Dee Ramone and others in the near future or do you think that chapter is closed?

I didn’t make that film but we felt fortunate if not guilty being able to release Rachel Amodeo’s film. The closest music scene film project I’m involved in now is my screenplay, ‘Naomi’s Darkroom’, which is about the life of SST’s photographer, Naomi Petersen. I wrote my book, ‘Enter Naomi’, after being shocked to hear she had died. For the screenplay I was able to make use of Naomi’s own journals so that her voice and story is not just something I made up, but reflects her own reality. I’ve also been working with Naomi’s brother Chris on her photo archive and we hope to get the film project going soon.

When did you first express an interest in music and what were some of the albums you were listening to early on?

I was born in 1955 and I think me and my brothers had a child’s 78rpm player by 1960. I also recall seeing the Kingston Trio perform ‘Hang Down Your Head Tom Dooley’ on television, maybe on ‘The WGN Barn Dance’. The Trio were up in the rafters of the barn’s set and leaning over and the lyrics scared me and I thought their heads might fall to the floor. I was probably 4 years old then. After an older cousin stayed with us for a summer she left her 45s of the Everly Brothers ‘Cathy’s Clown’ and Ray Charles ‘Busted’ and I was able to play those on my parents record player in 1963 when I was 8. I started listening to the radio (WLS, WCFL) then too.

What were your first endeavors into music like?

I used to go around and record my brother’s band, Midknight, when they played the schools around Naperville in the mid-70s. They were an instrumental prog band under the influences of King Crimson, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Jim Hendrix, Hawkwind and others. Feeding Tube Records just released an archival LP called ‘1975’ from those tapes last year – it’s pretty good! I tried to convince them to move to Hollywood when I got out there but they broke up. Now they are sort of back together.

You moved to Los Angeles in 1976 intending to write screenplays, but soon drifted into the music business. It must have been a very exciting time for music lovers back in the seventies?

Well it seemed like the presentation of early punk rock was semi-joking when you got to hear the Ramones on KROQ or the Sex Pistols on the KWST import show. If you were me it struck you as a retrenchment away from the keyboards and soloing of hard rock back to a direct garage rock presentation. That Black Sabbath, et.al. were losing focus meant that punk could refocus guitar rock. But only in Los Angeles did it seem like there was just enough media support from the daily papers and KROQ, KPFK, and college stations to allow Slash, Dangerhouse, SST, Poshboy and Frontier to sell records in a large market of kids. It’s still not that well understood that if the rest of America had been as advanced as Los Angeles had been in 1981 the first X and Black Flag records would’ve been gold records. But they were barely available in one or two shops in the other major cities.

“My approach to things was to be open to any outlet”

You started to work at Systematic Record Distribution, making important releases by artists like Pere Ubu, The Birthday Party and Dead Kennedys and labels like Dangerhouse, Rough Trade and Factory available to more shops. Would you like to tell us more about your work at Systematic Record Distribution?

It was growing slowly from 1978 in Portland, and we did a push after moving to Berkeley so that when Rough Trade opened their US company also in Berkeley later in 1980 we could split up our accounts and give them half the shop accounts we’d developed as their American outlet and the best source for American hardcore releases as well as other independents and imports. Gradually other American distributors which had been importers of major label UK punk turned their attention to what Systematic was doing and began to lock independent releases into exclusive distribution deals. My approach to things was to be open to any outlet and not tie anyone up by promising too much in exchange for exclusivity. This worked better for SST’s distribution over the long run than it did for Systematic on the other end; it went under in the late 80s. I think when we moved Systematic from Portland in late 79 we should have moved it to LA where it might have been able to survive but Rough Trade had decided on San Francisco. But it’s all academic in this digital wireless age.

Eventually you became a partner in the legendary SST Records. How did that come about?

Systematic carried the early Dangerhouse and Slash labels but our best sellers at first were things we imported from Rough Trade like Joy Division and Young Marble Giants. Those records just kept selling by word-of-mouth in 1980. Then suddenly younger kids started showing up at our accounts shops and buying D.O.A., Dead Kennedys, Black Flag, Avengers, Adolescents, Misfits, Minor Threat, etc., in even larger quantities. The founder of Systematic, Peter Handel, told me that he never thought that stuff I was ordering would sell like that. He was a Portland hippie who like the Rough Trade hippies really preferred reggae to punk. Systematic’s in-house label was called Optional Music and we tried to start it in Portland with the Neo-Boys. The local bands seemed less interested than the Dead Kennedys did when we bought their first 45 from them and booked them into Portland. They thought it was great we would be moving to the bay area so once we moved we started our label with the re-issue of Dead Kennedys ‘California Uber Alles’ 45. Then we pressed 3,000 of their 2nd 45, ‘Holiday in Cambodia’, and released the ‘Live at the Deaf Club’ album, ‘Can You Hear Me’ which featured the Dead Kennedys and other San Francisco bands. So we were doing alot of stuff at Systematic and of the labels I stocked I thought SST Records was the most interesting. They released the Minutemen’s debut ‘Paranoid Time’ and I saw Black Flag, Minutemen, Saccharine Trust, and The Stains up in SF so I got to know that they had some trouble getting everything that Spot was recording released since Black Flag ran the label themselves. Then they started touring to the east coast in late 1980. So in July 1981 when I was visiting family in Chicago I went to their gig at Tut’s. They were bring Henry back with them to be the new singer but Dez was doing the last few dates up to Minneapolis. So I offered to come down and run their office if they needed someone. Greg was interested so we made a plan. They’d been run out of Hermosa Beach and then Torrance just as they left on that tour. I got down to the new SST in West Hollywood at Unicorn Records and Studio in Sept 1981 in time to see them finish up work on the album and to see the second Henry-on-the-mic gig at Cuckoo’s Nest. I didn’t work much on the ‘Damaged’ album since Unicorn was distributing that but I focused on getting the Minutemen ‘The Punch Line’ and Saccharine Trust ‘Paganicons’ released and the first Meat Puppets album recorded. By April 82 we moved SST down to Redondo Beach where I felt like I was really in the environs that produced Black Flag.

From 1981 to 1986 you were an A&R man, record producer, and co-owner of SST Records. How was it to work with bands such as the Minutemen, Saint Vitus, the Meat Puppets, Black Flag and Saccharine Trust. Do you have any crazy stories you would like to share about it?

It was great to work with these bands. Black Flag had this standing that might be hard to explain today. Nobody had really done full touring across the country on an independent basis yet. D.O.A. and Dead Kennedys had done a few shows and west coast bands kept running up and down the coast Vancouver to San Diego. But clubs around the rest of the country didn’t understand who was calling them or whether anyone would show up. Nobody ever had showed up before for bands without label support or radio exposure. When Black Flag built that circuit by booking themselves other bands of their generational cohort respected them and everyone on or at the label. It made things easier. Chuck Dukowski eventually built Global Booking into an SST satellite world. And I think Naomi Petersen was better treated by bands than she might have been because people knew of her as SST’s photographer and that was legend already when she moved to DC or travelled to Europe. I tried to avoid the “happening” style gigs where Black Flag would play in someone’s house until the cops showed up or when Meat Puppets and Minutemen played on a boat in San Pedro harbor. I’m sure I missed some great music but I didn’t want to go to jail or go down with the ship. I got my fill at the clubs around town. I probably saw the Minutemen and Descendents once a week for years, Black Flag every couple weeks, Saccharine Trust and Meat Puppets every month, and Saint Vitus every couple months. At SST I sort of lost the awareness I had had at Systematic of what-all was going on around the country but it was worth it.

What about your own label, Thermidor Records? The label released some incredible albums by The Birthday Party, the Minutemen, Oil Tasters, Flipper, Nig Heist, SPK and Special Affect…

I started Thermidor with Jon Boshard who was an MFA student at UC-Berkeley and he did a radio show on the school’s radio station KALX. He had some money and wanted to do a label and I was frustrated that I couldn’t convince Peter to do more releases on Optional Music label. Most of the early Thermidor releases came about via my work at Systematic but once I moved down to SST Jon did most of the planning and I just oversaw the mastering and manufacturing in LA. Jon and I sat down with Graeme Revell of SPK after their San Francisco gig and talked to him about doing an album; Graeme’s face was still covered with blood from the pig’s head he had been hitting with a machete while he sang. The most surprising thing about the Thermidor roster is that decades later ONO has gotten back together and put out great new albums and finally started touring the country.

Would it be possible for you to choose a few collaborations that still warm your heart?

Overall I’d say that it was most fun working with Mugger and Spot. I described them in one of my books as looking like they were the rockstars when they all piled out of the van on those early Black Flag tours. Black Flag were mostly quiet guys but Spot and Mugger were funny ice-breakers who got the party started. Mugger made working at the SST office more like working at a parody of the straight workaday world, and going with Spot to K-Disc or the pressing plants or recording studios was a similarly fun way to learn about the technical side of things.

How are you currently coping with the world pandemic and what are your predictions for the music industry?

I’m getting alot of writing done, witness the ‘Western Stories’ collection, as well as the ‘Naomi Petersen’ script. Unfortunately the pandemic led every screenwriter to focus on writing while the producers slowed down so there’s a glut of scripts right now. I’m hoping the slack is taken up soon by the streamers productions. This should be a new golden age of programmers and b-movies. But I’ve long lost track of how the current record business operates. I use Facebook to share YouTube music clips and info on films playing TCM or the Westerns channel. I like to explore and share forgotten or unknown corners of music history via YouTube, including alot of the reggae singles I got introduced to when I was at Systematic. But then every year or so you just want to hear your favorite Hawkwind or Steppenwolf again.

Please take a moment to recall the lyrics of ‘Jesus & Tequila’ by the Minutemen.

When we moved SST down to Redondo Beach, D. Boon moved into SST once Black Flag was out on tour for ‘Damaged’. He was a great guy and it was nice to have him help out then when Mugger was still part of the touring crew. I mostly listened to the country music stations during the work day so we got to thinking about D. making a country album. He grew up on the Bakersfield sound so was interested in that idea so I started writing songs for him. I got three done but he only worked ‘Jesus and Tequila’ out and then when Minutemen decided to make their next album a double-album Mike put out the call for lyric contributions and so it wound up a Minutemen song and we never got the solo album idea done; the Minutemen started to tour and got just got too busy right up until the end.

Is there anything we have not addressed that readers should be made aware of?

Maybe I should mention my occasional blog, The New Vulgate, which has some of the stuff I put into my essay anthology, ‘Life Against Dementia’. And the books are available at my local shop’s website (link), or at Amazon. Quimby’s in Chicago and Brooklyn carry them and Stories Bookshop in LA does as well.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thanks for the questions; hope the answers are to the point and long where you want them long.

Klemen Breznikar

Joe Carducci Facebook