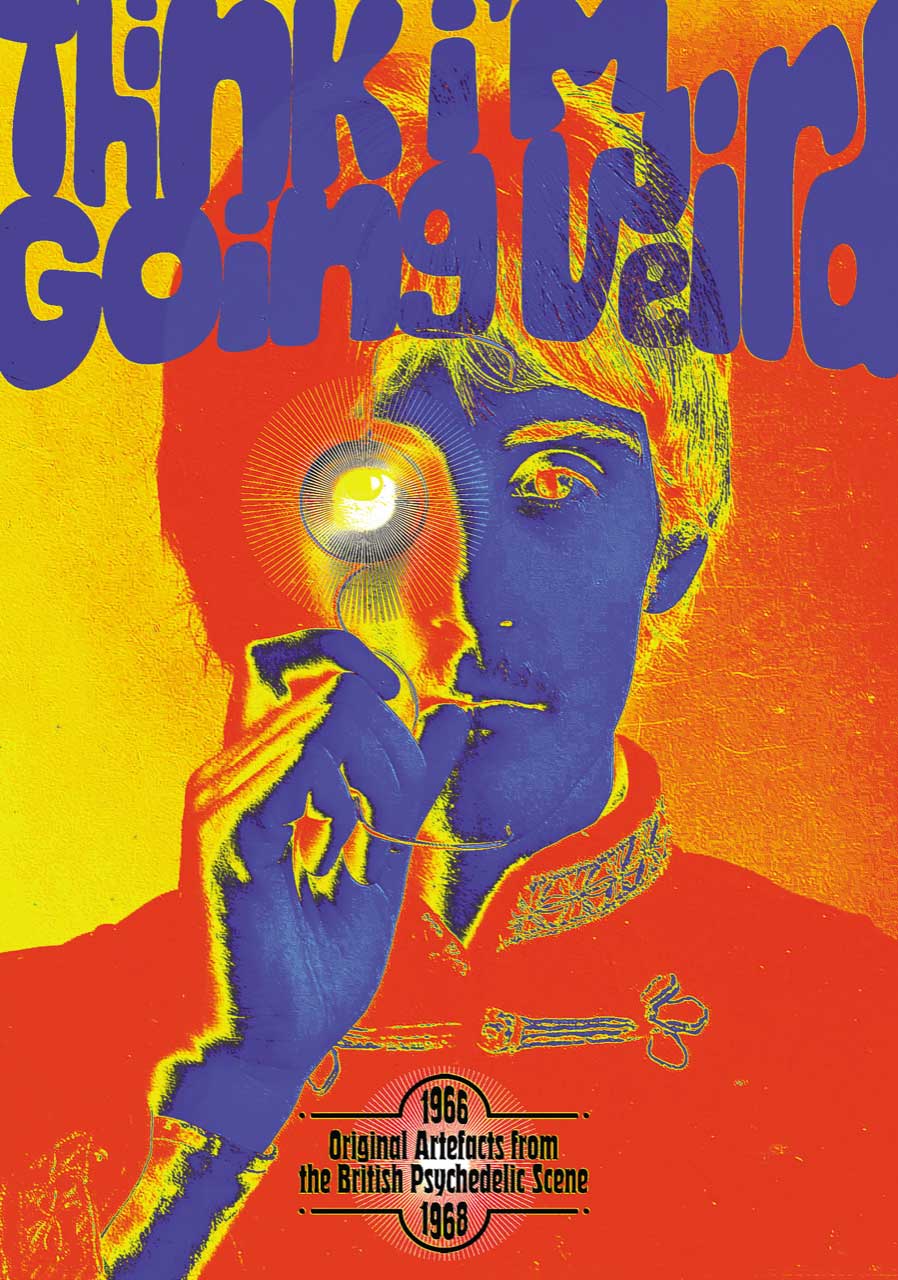

Think I’m Going Weird: Original Artefacts From The British Psychedelic Scene 1966-68

“A slice of surprising history, history some people hope will never be repeated again,” narrates a suitably plum-voiced commentator, a bus painted in vivid colours sitting in the foreground of a pastoral scene. Clutches of small tents and tepees have been erected on the grass near it.

Young people stroll by here and there, some with flowers tucked behind their ears, others donning Indian-styled headbands, and all dressed in bright, eye-catching fabrics. It is the height of the summer of 1967, the famed ‘Summer of Love,’ and British Pathé are covering a music festival on the grounds of stately Woburn Abbey- the so-called ‘Festival of the Flower Children.’

“Brace yourself for it and prepare yourself to meet- in some sort of action- a ‘hippie.’ This is history, alright!”

“One-stop psychedelicatessen”

But something isn’t quite right. Much of the hippie attire on show looks a little too uniform, too streamlined, too mass-produced- indeed, some attendees appear to be wearing identical shirts. For 1967 standards, many of the men filmed at the festival wear their hair cropped short even by the fashions of the contemporaneous mod scene. A number appear as though they’d be more likely found spending their weekday afternoons in a grammar school classroom instead perusing the bohemian tomes on sale at Barry Miles’ Indica bookshop. Most look as though they’d rather sink a pint of Stella Artois than drop a sugar cube of L.S.D.

In short, the festival at Woburn was indeed “history, alright,” in that it represented the cultural shift witnessed when psychedelia slipped out from London’s underground musical dungeons and into the mainstream cultural conscience- the moment revolution transformed into trend, flower power into fashion.

As the beatniks of the previous generation and the punks of the next could have readily attested, the spill-over of underground youth culture onto the overground is an inevitability, but the speed at which the psychedelic movement was subsumed into the mainstream remains unprecedented to this day, even if it was only a matter of time before it did so.

After all, between the summer of 1966 and the spring of 1967- a period evocatively portrayed in Peter Whitehead’s 1968 documentary, ‘Tonite Let’s All Make Love In London’- the swinging city’s in-crowd inhabited a veritable creative pressure cooker.

As DJ Johnnie Walker recalled, “as we went into 1967, one had the feeling that it was going to be quite a profound year. It was almost like the revolution that started in 1963 had really gathered pace and was going to lead to really big changes.” Echoing the same sentiment, photographer Gered Makowitz described how “there was an awful lot going on in all areas.”

“It was exciting to be part of it, and it was momentous perhaps because everybody began to say that this isn’t a passing fad. This is our lives and our culture for our youth and for a lot of other people.”

With the debut of the underground newspaper International Times (or IT) onto the scene in October 1966, the embryonic counterculture gained a focal point through which to communicate and organise ‘happenings’ (multimedia events combining music, performance art and audience participation)and, when Joe Boyd and John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins founded the UFO Club in the basement of an Irish dancehall by the name of ‘The Blarney’ on Tottenham Court Road two months later, the early flower people found a bona-fide natural habitat in which they were free to express themselves on both a personal and artistic level.

Nights at the UFO Club were eclectic affairs, perhaps the closest Britain came to replicating the fabled ‘acid tests’ staged by Ken Kesey and his ‘Merry Pranksters’ over in the States. As Joe Boyd put it in his autobiography ‘White Bicycles’, “at UFO, the grinning crocodile of psychedelics wrapped its lips around your ankle, dragged you in, and licked you all over,” and the entertainment laid on for its clientele of night trippers- a motley band of movers and shakers that often included such celebrity alumni as Pete Townshend, Jimi Hendrix and Paul McCartney- was suitably diverse.

On any given night at UFO, audiences could be entreated to the projected films of Kenneth Anger and Andy Warhol, free-form jamming led by the Giant Sun Trolley in which the line between performer and audience was often blurred, African drumming, recordings of Indian sitar music, Disney cartoons, experimental dance from the Tales of Ollin dance group, poetry from Pete Brown or the Liverpool Scene, Dadaist humour from the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, jug music from the Purple Gang, liquid lightshows put on by Mark Boyle, ‘IT Girl Beauty Contests’ and, as the police began to take a more provocative stance against the alien new subculture, even ‘Spot the Fuzz’ competitions to root out plain-clothes drug enforcement agents.

It made for a dizzying melting pot of many disparate influences, but one band in particular captured the attention of the nascent movement. Led by the elfin Syd Barrett, ‘The Pink Floyd’ were regular performers at the UFO from its inception through to their own meteoric rise to fame off the back of the consecutive hit singles ‘Arnold Layne’ and ‘See Emily Play,’ routinely performing all through the night with extended renditions of their proto-space rock anthems ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ and ‘Astronomy Domine.’

Beloved by the underground and considered -alongside the lesser, but pioneering nonetheless Soft Machine and, later, the Keith West fronted Tomorrow- to be the UFO’s primary ‘House Band,’ Pink Floyd were the first, most prominent, and longest-enduring act to emerge into the mainstream from the new subculture centred around the UFO. That isn’t to say that Pink Floyd were Britain’s first psychedelic band, but, rather, that they were the first born entirely from the medicated gooof the burgeoning counterculture. Others, like former R&B band turned freakbeat pioneers the Yardbirds, had already established sizeable audiences for themselves earlier in the decade before taking the leap into psychedelia.

Appearing on ‘Top of the Pops’ a number of times to promote ‘See Emily Play,’ Pink Floyd became unlikely popstars, leading to ever-greater queues at the UFO and distilling the early anarchic avant-garde essence of the underground.

And, as the summer nights began to stretch out, all was not as rosy as it may have seemed in what Mick Farren dubbed “Hobbit Heaven.” The spring of UFOria was giving way to something of a media frenzy comparable to that faced by the hippies across the pond in the Haight Ashbury, and with such heavy attention came unwelcome scrutiny from the authorities.

The ‘International Times’ office was raided by police a number of times in an apparent effort to force the paper out of circulation, while UFO buckled under the unexpected strain of catering to so many new patrons. The club was in increasingly dire financial straits, and, after a highly exaggerated sordid news report on the supposed salacious conduct of the UFO’s clientele, the Blarney’s landlord insisted on UFO leaving his premises and the club was henceforth relocated to the Roundhouse.

Another bad omen came when John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, one of the most important figures in the incubation of the London underground, was himself arrested for cannabis possession on June 1st, 1967. He was imprisoned for six months, missing the summer of flower power he had himself been so instrumental in planting.

The same day that ‘Hoppy’ was busted, a rather important album was released. Although some copies were rush-released ahead of schedule on May 26thso as to sate the rabid appetites of expectant fans, the 1st of June, 1967 saw the official issue of the Beatles’ eighth studio L.P, ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band.’

Housed in an iconic sleeve depicting the four now-moustached Beatles posing in colourful Edwardian style military uniforms before a congregation of cardboard cut-outs of their creative influences, ‘Sgt Pepper’ was nothing short of ground-breaking. An ingenious hybrid of psychedelia, baroque pop, vaudeville, music hall, Indian classical and tape collage, it was an instant hit that soared to the top of album charts across the world.

In the long term, it forever altered how pop music was made, packaged, and listened to; in the short term, it brought psychedelic music to the masses. Where once acid rock was a fringe subgenre that had to be sought out in underground clubs like the UFO, it now blared triumphantly from every turntable and every radio like the brass band backing the Beatles’ alter-egos on the title track of their bestselling album.

Somewhat fittingly, as the Fab Four finished and finessed their masterpiece in the spring of ‘67, in the adjacent studio in Abbey Road were none other than Pink Floyd, beginning work on their debut album ‘The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.’

While many in the music industry saw ‘Sgt Pepper’ as an aural manifesto for the future, in many ways it was, in reality, a day-glomonument to what had, ifonly fleetingly, already come before. It was an expression and a product of, the Beatles’ own experiences in an underground scene now creaking past the point of critical mass.

The album’s millions of awestruck fans, however, did not hear an epitaph to the dazzlingly experimental days of the hippie era’s prelude; they did, however, hear a new beginning. ‘Sgt Pepper’ (not to mention the preceding and highly influential double A-side single, ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’/’Penny Lane’) was duly pilfered by a myriad of imitators for its every novel recording method and motif, providing something of a benchmark, a doctrine, even, for what the previously ill-categorised genre of British psychedelia was meant to sound like.

Accordingly, unlike the concurrently angry sounds emanating from acid rockers like the Doors and the Jefferson Airplane from the West Coast of the Vietnam-embattled United States, British psychedelia often took on a gentle, playful, even childlike tenor. A propensity for nostalgic whimsy and bucolic Lewis Carroll surrealism could be readily observed in the dozens of new psychedelic bands emerging across the country.

Opium-haze evocations of fusty Victoriana and British Empire exotica were performed by bands who donned not denim work shirts and jeans like their contemporaries in Laurel Canyon, but instead embraced a Beatles-inspired peacock dandyism defined by floral prints, ruffled shirts, John Lennon-style granny glasses, flowing silk scarves and velvet frock coats in paisley brocade purchased from boutiques with such evocatively appropriate names as ‘Granny Takes a Trip’ and ‘I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet.’

As such, by the mid-summer of 1967, ‘flower power’ had already become the pre-eminent trend in popular culture, leading directly to such heavily commercialised attempts at monetising the phenomenon as the Woburn Festival of the Flower Children.

The event in question was not without some semblance of hip credibility. ‘Blow Up’ stars David Hemmings and Vanessa Redgrave were in attendance, as was the model and future girlfriend of Syd Barrett known as ‘Iggy the Eskimo.’ There was DJying between acts courtesy of Jeff Dexter and John Peel- the latter of whom was a major underground celebrity on account of hispsych-sympathetic ‘Perfumed Garden’ night-time show he had hosted on the by then-defunct pirate radio ship ‘Radio London’- and the line-upeven boasted such cult classic acts as Tomorrow and Dantalion’s Chariot together with popular chart groups like the Bee Gees and the Move.

Nonetheless, the festival at Woburnis widely considered less a genuine ‘love in’ than a cop-out, a money grab aimed at exploiting the idealism of the underground. Even Pathé’s newsreel narrator concedes that a number of those in attendance were in actuality “part-timers,” cultural tourists “simply trying to meet with those who have REALLY contracted out of normality.” There was outrage at the selling of over-priced hot dogs (two shillings!) and the presence of sale racks of knock-off hippie clothes from opportunistic Carnaby Street vendors, and, somewhat symbolically, a rather shambolic scuffle over carnations dropped from a hot air balloon broke out.

But, authenticity aside, the Woburn venture served as further evidence to the music industry at large that psychedelia was indeed a profitable business- that it was a sensible rocking horse to gamble upon in the zeitgeist moneygoround. The appropriately named Seller brothers (who owned the mod nightclub ‘Tiles’) who organised the event had, after all, come away £20,000 richer.

Of course, the encroaching commercialisation of the underground drew the ire of many who helped to instigate the scene, and, before long, the last vestiges of the first wave began to wash away. The first nail in the coffin came when the UFO Club was forced to close its doors in October 1967- prompting Melody Maker magazine to pre-emptively ask, “Who killed flower power?” It was hardly a promising sign of things to come. How could the underground carry out a cultural revolution if they could not manage to keep a successful nightclub open?

Meanwhile, many key figures began to gravitate away from psychedelia into other pursuits- be it forays into Indian spirituality in the path of George Harrison or following the next-big-thing allure of the almighty Henley-shirted blues boom that took over the London music scene from mid-1968 onwards. Some mimicked Traffic’s Berkshire cottage migration and left London to “get it together in the country” while others, like Graham Bond, immersed themselves into the world of the occult. Others still- Syd Barrett most tragically amongst them- flew too close to lysergic suns in supernova and were never the same again.

Some bastions of flower power kept the spirit of ‘67 alive in the country’s capital, namely Covent Garden’s ‘Middle Earth’ club. London’s new hippie headquarters, it held on until 1969, regularly hosting the likes of Fairport Convention, the Pretty Things, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, and Tyrannosaurus Rex until it, too, closed down. By that time, it was abundantly clear that London’s Summer of Love was nothing but a distant, if beautiful, memory.

It’s influence, though, like the persistent smell of incense, was yet to dissipate. Flower power was not dead yet- it had just moved further afield. The alchemists of the UFO had created a Frankenstein’s monster in kaftan and beads over which they no longer had control as, over the twelve months of 1968, it stomped its way across the U.K in its snakeskin boots and crushed velvet flares, painting the provinces purple and giving their residents a taste of what had swept over London in the spring and summer of the previous year.

There was seldom a period of greater creativity in the annals of British popular music history than the imaginative upheaval that took place between 1966 and 1968, and as such it is not surprising that dozens of attempts have been made to retrospectively catalogue and encapsulate the psychedelic boom over the years- the ‘Real Life Permanent Dreams,’ ‘Acid Drops, Spacedust and Flying Saucers, and ‘Nuggets II’ box sets chief amongst them, to say nothing of the formidably sprawling multi-L.P ‘Rubble’ collection.

But, with their landmark 100th release, Grapefruit Records may well have compiled the definitive final word on a genre that has long delighted casual music fans and serious music archivists alike with their brand-new title, ‘Think I’m Going Weird: Original Artefacts from the British Psychedelic Scene 1966-1968.’

Comprising five discs housed in a 60-page, A5 book format with 25,000-word track-by-track annotation penned by the ever-knowledgeable David Wells, ‘Think I’m Going Weird’ is nothing short of a masterwork, a fitting achievement for the Cherry Red subsidiary long upheld as a beacon for the preservation of obscure psychedelia. It’s a gorgeous package, brimming with new information and rare photographs that firmly place the recordings in the context of their history. Even when rated against their recent achievements on the reissue front- with long-thought lost recordings from deep-cut favourites Tintern Abbey and the Syn, for instance, finally seeing the light of day thanks to their work earlier this year- this particular set ranks as perhaps their most expansive and accomplished effort to date.

Short of including major artists like Pink Floyd, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Donovan- the absence of whom, it can be fairly presumed, is the result of contractual issues in licencing- just short of every major and minor psychedelic band make an appearance. Soft Machine and Tomorrow, Small Faces and Kaleidoscope, the Creation and the 23rd Turnoff, Blossom Toes and Orange Bicycle: all and more have a moment in the sun over the course of ‘Think I’m Going Weird.’ It really is, to borrow David Wells’ description, a “one-stop psychedelicatessen.”

Of course, this being British psychedelia, there’s plenty of fantastical names that verge on parodic- even if ‘The Zany Woodruff Operation’ might just take the cake- and an enormous spectrum of sounds, themes and stage gimmickry to wade through.

One minute there’s the swirling circus-calliope tale of a failed poet (Granny’s Intention’s ‘Story of David’), then there’s Zoot Money’s Dantalion’s Chariot doomily pondering subterranean life in the wake of an apocalyptic nuclear war (‘World War III’). Simon Dupree and the Big Sound are surprisingly convincing in their reverb-drenched pot-shot at the growing portentousness of the genre under their assumed Pepper-esque aliases of ‘the Moles’ (We Are The Moles pt.1 and pt.2). Furthermore, there’s jaunty, jangly Carnabetian harmony pop (‘I Know She Believes,’ Picadilly Line) and even are-vamped Depression-era cover performed by double-breast besuited faux gangsters (‘Brother, Can You Spare A Dime’ by St. Valentine’s Day Massacre). By the time Disc 5 fades out with the Action’s soulful wah-wah workout ‘Brain’, from their aborted album project ‘Rolled Gold,’ barely a stone has been left unturned.

Indeed, ‘Weird’ perceptively strays into related subgenres often not collected on compilations of this kind that nonetheless played a key part in the development of the British psychedelic sound. Although the gentle instrumental ‘Bun’ finds them in more benign form than the fuzz-laden proto-punk they were more renowned for, the Mick Farren (UFO’s straight-talking doorman) fronted Deviants are seldom compiled despite their heavy live presence during the Summer of Love and beyond. This is fortunately rectified by their inclusion in this set. Acid folk is represented by the brambly sitars of the Incredible String Band’s ‘Mad Hatter’s Song,’ and the uncategorisable Third Ear Band are finally aligned on tape with those bands they performed with all too often at the likes of the UFO, the Drury Lane Arts Lab, and the Hyde Park Free Festivals. The uncanny, Middle Eastern-inflected, gradually building drone of ‘Cosmic Trip,’ included on Disc 4, was recorded only a couple of months before the Third Ear Band provided the soundtrack for John and Yoko’s first ‘bagism’ stunt at their December 1968 ‘Alchemical Wedding.’

This sweeping overview accomplishes that elusive aspiration for compilations of this timeframe: the presentation of its material in a manner that feels fresh and not akin to re-treading tired old ground. As can be expected, certain genre favourites cannot be overlooked and are once again given another airing- namely the hard-charging rave up of the Yardbird’s ‘Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,’ the reptilian slither of July’s ‘My Clown,’ the warping head-trip of the Who’s ‘Armenia City In The Sky,’ the relentless motorik riffing of the Factory’s ‘Path Through The Forest’ and the freakbeat trance of the Pretty Things’ ‘Walking Through My Dreams.’ They may all sound like old friends to serious fans by now, but, arrayed beside a stunning 50 minutes of previously unreleased music, their inclusion does not come across as contrived. If anything, they are recontextualised, given a new lease of life.

The vast quantity of hitherto unheard music presented here is nothing short of an amazing archival accomplishment, showcasing the sheer scale of the width and breadth of the psychedelia’s influence upon the industry. There are demos from, to name but a few, Medium Rare (who recorded ‘Plastic Airplane’ mere months after supporting Procol Harum in Torquay in June 1967, whilst they were still at the top of the charts with the quintessential Brit-psych blockbuster ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’), Crystal Ship (whose contribution, ‘The Blue Man Runs Away,’ features lyrical contributions from Cream songwriter Pete Brown) and London live scene stalwarts Tinsel Arcade, represented with their blistering September 1967 demo, ‘Life Is Not What It Seems.’

Most excitingly for psych enthusiasts, however, is the excavation of a psychedelic holy grail in the first commercial release of a recording by 117, a band so legendarily obscure that it shared its name with a psychedelic fanzine published in the 1990s.

Sourcing their suitably cryptic name from the number of earth days it takes for the sun to rise on Venus, primary sources indicate that 117 were practically omnipresent in London’s underground clubs throughout the spring and the summer of 1967, featuring as they do on handbills and posters for gigs staged at every psychedelic venue of note. The semi-mythical group performed at perhaps the seminal underground happening of the entire British psychedelic era- the ’14 Hour Technicolour Dream’ at the Alexandra Palace on April 29th, 1967- and even found themselves the subject of a bizarre sequence in another Pathé’ newsreel that same year, laying down the soundtrack to an unusual sci-fi ‘happening’ in a London park.

Only a brief snippet of audio of 117 playing could be heard on the aforementioned newsreel, and the band’s recorded legacy was long thought lost to history- until now. A murky live recording of ‘Venusian Moonshine’ recorded live at the Middle Earth Club closes out disc 4. One of two songs cut at a lost session at Olympic Studios (allegedly featuring Mick Jagger on backing vocals), the recovery of this snippet of previously missing psychedelic history more than makes up for the admittedly shaky quality of the source recording.

As 117 organist Charlie Hart recalled, Rolling Stones producer Andrew Oldham was present for the still-missing Olympic session and “wanted a three-minute pop single, but we weren’t really a pop group- we were stoned students really, closer musically to Country Joe and the Fish.”

“But they were great days. The whole thing was idyllic.”

By the end of the extended ‘Summer of Love’ period of 1966-68, the world hadn’t changed perhaps quite as much as the dreamy-eyed cosmic visionaries of the flower power movement would have liked to admit. The war in Vietnam still raged, peace and love were far from universal, racism and hate still boiled: in other words, the utopian society that had been trialled by adherents to the hippie lifestyle was, sadly, not feasible on a global scale. It all was too idealistic, too naïve for this world.

But, just because existing power structures weren’t toppled and acid drenched Shangri La soon devolved into drug dependency and the premature deaths of many early proponents of the psychedelic movement, that isn’t to say that this oft-exhumed era wasn’t an immensely important period of development for Western popular culture. The ideals of the time and the questioning attitude of subversion and self-expression remained with the survivors of the Summer of Love and further impacted not just the music of future generations but also their chosen lifestyles, be it in the form of reactionary backlash in the case of the punks of 1977 or updated homage as staged by the acid house ravers of 1989.

The philosophical and anthropological outcomes of the Summer of Love period, however, are of ancillary concern to most casual music fans. What really matters- and, as ‘Think I’m Going Weird’ proves- this truly was a prime age for popular music. There evidently was something in the air fuelling all of that wonderfully adventurous creativity.

“There was definitely a vibe,” reminisced George Harrison of the timeframe, “we could feel what was going on with our friends and people who had similar goals in America. You could just pick up the vibes, man.”

Fellow Beatle Paul McCartney explained how “the year 1967 seems rather golden.”

“It always seemed to be sunny, and we wore far-out clothes and far-out sunglasses. Maybe calling it the ‘Summer of Love’ was a bit too easy, but it was a golden summer.”

‘Think I’m Going Weird’ is a triumph, capturing a halcyon time in a way that few others have achieved at present- and likely ever will. Not only is it an obvious must-have for those who know their Plastic Penny from their Mabel Greer’s Toyshop; it also makes for a fascinating historical document of possibly the most revolutionary 36 months of the post-war era.

As Grapefruit’s other year-by-year sets attest, there was still much great music to come well into the 1970s, but the very nature of the wide-eyed innocence of the British psychedelic era can be difficult to reconcile with clinical, classically trained intelligence of the progressive rock the genre morphed into. Granted, there are no shortage of Brit-psych tracks that are saccharine to the point of twee, but therein lies a lot of the charm.

And, as David Wells realistically observes, with the 1960s generation quickly reaching advanced age, it is more important than ever to preserve even the most obscure recorded relics of that far-off decade.

“Many of the musicians from that era are sadly no longer with us,” he writes in his introduction to the set, “and, without being morbid, some of the survivors are not in great health: we’ve therefore taken the view that it’s important to chronicle a fascinating but now seriously distanced scene while it’s still possible.”

Grapefruit Records have managed all of that and more with ‘Think I’m Going Weird: Original Artefacts from the British Psychedelic Scene 1966-1968.’ Surely, the frequently disinterred 1960s goldmine must be close to running dry, and it’s unlikely that future anthologies will be able to source anywhere near the sheer volume of quality unreleased recordings that Grapefruit have presented to their fans for their 100th release.

This may well be the most important British psychedelic release since the ‘Rubble’ collections of the 1980s, filling in the missing pages of a genre that continues to excite even now, over fifty years later.

Jack Hopkin

Think I’m Going Weird: Original Artefacts From The British Psychedelic Scene 1966-68, 5 CD (Grapefruit Records 2021)

Beyond The Pale Horizon – The British Progressive Pop Sounds Of 1972

Various Artists – ‘Sumer Is Icumen In: The Pagan Sound of British & Irish Folk 1966-1975’

‘Peephole In My Brain- The British Progressive Pop Sounds Of 1971’