Penny Rimbaud | Interview | “I influence myself the most when it comes to anarchism”

Penny Rimbaud is a writer, poet, philosopher, painter, musician and activist. One of the most prolific punk pioneers is still very active these days. Together with Martin ‘Youth’ Glover they recorded a collaboration album ‘Corpus Mei’, out via One Little Independent Records.

“Recording and writing this album was an intense and wonderful experience” Youth tells us, “Penny is one of the great visionary poets of our generation. A seer and prophet… crying to the universe, alone up on the mountain. Part Blake, Part John the Baptist and part Buddha. His is the limb nailed to the cross of our cultural banality. Such a narrative demands a suitably epic backdrop. Composing and producing this music, as a foil to Penny’s beautiful and terrifying, almost biblical monologues, has been one of my greatest achievements in over 40 years of making music. The themes reveal Penny’s almost psychic pre-cognition of today’s dystopia and the sudden slo-mo apocalypse were all living through now. Nevertheless, it leaves you with a feeling of hope, inspiration and many positive possibilities. This was a great challenge and a deep channeling in itself. Despite the serious nature of the work we were mostly laughing and really enjoying each other’s company, the sessions were filled with joy and love”.

In a series of epic, cinematic soundscapes, Penny spits tales of the grotesque and absurd. Gargantuan sermons delivered in counter to swelling, emotive orchestration where he and former bandmate Eve Libertine deliver a slew of anti-capitalist weaponised poetry.

Working in association with One Little Independent Records, Penny Rimbaud is pleased to announce the launch of Caliban Records, a new label specialising in new music or, as he himself puts it, “that which might not otherwise get the hearing it deserves”. Caliban’s first release will be ‘Kernschmelze III – Concerto For Improvised Cello’ in which Rimbaud supplies electronic backing to the sonic wizardry of cellist Kate Shortt. Future Caliban releases will include Dominique Van Cappellen-Waldock’s ‘Fleur de Fleu’, a drone-driven threnody to loss, Mikado Koko’s ‘To Our Other Selves’, a radical “cut-up” of Rimbaud’s seminal ‘Acts of Love’, and Diane McLoughlin’s ‘The Casimir Connection’, playing new compositions bringing classical sensibilities to the freedoms of jazz.

Crass have also announced a new vinyl reissue series repressing their limited releases of adjacent artists through Crass Records, in association with One Little Independent Records. The first of which are by Honey Bane and Jane Gregory, out now.

‘Corpus Mei’, the collaboration album from Penny Rimbaud and Youth is available now digitally and on vinyl/CD.

It’s really wonderful to have you on It’s Psychedelic Baby! Magazine. How have you been in these horrible times of pandemic?

Penny Rimbaud: Contemplative.

Did you ever think that the world would turn for the worse so quickly? Pandemic, poverty, climate crisis. It feels to me that deep down inside we all knew that it’s already happening, but ignorant society just didn’t see the problem until the pandemic burst in flames. What are your predictions for the future? It is just hard to believe that we are moving into George Orwell’s novel for real.

I don’t think things really have particularly changed in terms of the usage of situations. The pandemic, be it manufactured in the laboratory or not, I tend to believe it was, is merely an extension of what we saw in the 20th century with two world wars, it’s an extension of what happened before in the industrial revolution, and that is the sort of exploitation and use of the population. I mean, the pandemic itself is simply a pandemic, you know, it’s another illness, a particularly unpleasant one because of the manner of its production, but that’s irrelevant. Is it more unpleasant than World War I? Are the trenches we’re in any more or less depressing, or barbaric? It’s an extension of our abuse of the planet, and notably our abuse of the human race. It’s quite extraordinary. I think you’re quoting 1984. I mean, that’s like a vicar’s Tea Party compared to the actual truth. What happens, you know, be it the first world war, be it Auschwitz, be it Hiroshima, be it pandemic. I mean, they’re all one in the same thing. They’re coming from a mindset which knows no love, basically.

‘Corpus Mei’ was recently released. When did you originally meet Youth and how did you decide to start working on this project?

So I originally met him doing a Charlatans album. I did a track ‘I Sing the Body Eclectic’ on The Charlatans album ‘Who We Touch’ because Tim was always a great Crass fan and asked me to come in and do a track, which I did. And Youth was producing and then sometime later he was producing a Bloody Beetroots album. And Bob from the Beetroots has always been a great Crass fan as well. And when he heard that Youth knew me as a contact he got in touch with me. Youth got in touch with me initially and asked if I wanted to do it, so I looked up the Beetroots on YouTube. It’s not really my thing you know, dance, electro dance stuff so I sent him a poem called ‘Black Man In The White House’ which was a sort of vitriolic comment on racism in America. Because I really objected to the huge celebrations of Obama’s presidency, you know, nothing changed in terms of the average black person’s existence, the racism went on unheeded and the mass incarcerations, which is what I particularly concentrated on, increased as they have always been increasing. There were something like two million incarcerated black people, you know, all mostly largely incarcerated around the war against drugs. Anyway, I sent that to Bob and said, “Well, okay, yeah, what about these lyrics?” and I really thought he’d write back and say, “piss off, I can’t deal with that”, but he absolutely loved them. So we carried on and produced that album. And it was really lovely. We did it with a full orchestra. Great track, I really enjoyed it.

And then I became very close to both Bob and Youth. And you know, we would be in touch with each other. And then Mark invited me to do a track for some sort of compilation and I did, and then Youth was listening to this and said “Oh, come on, let’s do an album together”. So we did. And basically, he’d got a load of tracks, which he’d got just in the cupboard sort of thing. Beautiful compositions. And he played them. I said, “Yeah, let’s just work with those”. So I just took up a big book of all of my poetry that I had at the time, and I’d listen to the track and then go, “Yeah, I think this one might work”. And that’s how we did it. It was very, very intuitive, there was sort of a symbiosis there, which was just so natural. It was a very, very natural product really. It came out of our shared sense of light and our shared sense of possibility. It was totally uncynical. I mean, I don’t think we particularly even thought about releasing it. As you probably know, we recorded it in 2012 or 2011. And it just sat on a shelf. So we forgot about it. And then he got in touch with me about two years ago and said, “Wow, why don’t we have another remix?” And I’ve never particularly liked the mix. So we did a remix together and that’s the result. But it was all very natural. You know, I’ve done a lot of work with different artists. And I don’t try to do anything, I’m there and do whatever they’re doing. What I mean is it’s not self-conscious. Neither is it in any way contrived. If I like what someone says, I’ll go along, and I’ll be with them. It’s more like being with people than worrying about what the product is. And that’s what interests me. That’s why I started Caliban Records so that I can offer that being with people to a broader spectrum.

“If you’re gonna talk the talk, you’ve got to walk the walk”

Can we also talk about your album, ‘How?, a reinterpretation of Allen Ginsberg’s classic 1954 poem ‘Howl’? When did you first get to know Ginsberg’s work?

When I was about 14, or 15, I don’t know how I heard about the beat poets, but I was very attracted to that. That would have been 70 years ago. Yeah, 1950 something or early 60s. Anyway, I just sort of heard about it, but I didn’t know about it. I just heard about it. Anyway, there used to be an American bookshop on Goodge Street in London. And I went there and I was too embarrassed, I was still a kid really, I was too embarrassed to go up and ask. And I saw this little paperback with a guy with a great big beard and sort of fedora. And I thought “Wow, that must be a beatnik”. So I bought it and on the train home I started reading and actually it was a book of Walt Whitman’s. You know, which would’ve been written 100 years before the beat, but he was a great inspiration particularly to Ginsberg. So that was the beginning of my lifetime of sort of enjoying the work and being inspired by the work. Primarily I love Whitman’s work, probably above anyone else’s in the field of poetry. But obviously, Ginsburg and Kerouac and Ferlinghetti and all that crew are just inspiring because they were working outside the frame and you know, there was an aspect of a bohemian lifestyle about what they were doing. I’ve always liked lifestyle. And I don’t mean that in some magazine sense, but I mean, if you’re gonna talk the talk, you’ve got to walk the walk, you know. And that’s been a very profound premise of how I tried to live. And so that was my affection for Ginsberg and my love of ‘Howl’ really, which was such a beautiful poem.

‘Howl’ seems to be very relevant to what’s happening in this era…

Well obviously what I did was, you know, Ginsberg who was basically one of the best minds of his generation destroyed on certain drugs and madness sort of parallels that. I had performed ‘Howl’ several times, you know, at the beginning of this century, and I was asked to do it for the London Jazz Festival.

And I can’t remember what year it was, 2003 or similar, and I was going to do it and up to that point I hadn’t thought copyright mattered. Because I was just performing at a jazz club, why bother with copyright? But I thought, well, if I was gonna go out on radio and be recorded, then I’ll find out about copyright. And I found out that it was actually published by Harper Collins, who are a wing of Rupert Murdoch’s industrial ownership of culture. So I thought “fuck that I’m not just not prepared to operate on that sort of level”. I can’t deal with that. And I was thinking how Ginsberg would just turn in his grave if he knew how he was copywritten, and by Harper Collins. So I thought, “Well, what do I do?”, I think, you know, the gig was about three weeks ahead. And then I learned that, I can’t remember if it was Reagan, or Bush or one of those lunatics coming over, and the very day of the gig was the day that whichever of those mad presidents was going to arrive in Britain. And it just seemed like everything was going wrong. So I thought “I’ve got three weeks, I’ll rewrite it”.

And so the best minds of my generation who were really destroyed by sort of capitalist greed, you know, be it the Murdoch owning ‘Howl’, or Saatchi owning the art world and like everything’s become just a commodity, blah, blah, you know, Bohemianism has sort of been eradicated. And so my rewrite, my modernization of ‘Howl’ used exactly the same number of lines, I think, exactly the same format, and even used one or two of Ginsburg’s lines. But generally speaking, it was about the sort of commodification of art and music and culture and the disruption of Bohemianism, which, you know, is a sad story.

“We were interested in living our own lives”

You’re an anarchist. How do you define anarchism and who influenced you the most, you think?

I influence myself the most when it comes to anarchism. I mean, we became anarchists, Crass became known as anarchists because we were pissed off with both the left wing and the right wing trying to sort of accommodate us, trying to get in on our story. “Well come and play for us” sort of thing. And it was equal from left and right. Both of them were sort of courting us to become their pet band. And one way of telling people to piss off out of it was to put a great big A at the back of the stage, which was one of our first banners and it really, it wasn’t meant to say we are anarchist, it was more meant to say “Fuck off. We’re not interested in any of your politics, be they anarchist politics, or leftist politics or rightist politics”, you know, we were interested in living our own lives in a good way. And sharing that in a good way. That’s what we’re interested in, which is a sort of a very fundamental anarchist principle, if you like, but generally speaking my experience of anarchists with a capital A, is they’re rather tedious and bigoted people who see lots of enemies around them, et cetera. I don’t see that. I think the prime is love, you know? And if you’re not coming from that place, then forget it, because you’re just going to add to the general sense of pain.

“2020 years of absolute mental dysfunction”

Would it be possible to make parallels with the political/social situation of the 50s and late 60s compared to what’s happening now, in this post Trump/Covid world? In those days art was shaping social movement to a larger degree than it’s happening today. Why is that, you think?

Commodification. Commodity ultra. Means sort of Debord’s spectacle, and that sort of thing has gotten way beyond the sort of rather small idea he had of the spectacle in the same way. And I mean, 1984 was, it’s like, so off the mark, really. I mean, pretty sad in its lack of prediction, I mean, people like J. G. Ballard were far better at sort of seeing futures. You know, I mean, and that’s actually because Orwell was hooked on political ideologies, and not looking beyond them, or around them or through them. So I think the degree of general ignorance remains pretty constant. As long as people are going to be stuck in the overriding narrative, the overriding narrative that goes right back to the time of the Greeks, and then there’s been little changes, alterations, the age of the Enlightenment was a sort of step out of the age of this scholars, et cetera. But it’s all one narrative. I mean, it’s one narrative based around Greek thinking, Greek science, and then Roman Empire thinking and science, et cetera. And as well any further than that – Christian, for God’s sake! People are still going to church! 2020 years of absolute mental dysfunction. It’s not a matter of faith, it’s a matter of mental dysfunction. So nothing’s changing.

You know, the colour of it changes. That’s all, the form of it changes, but it’s still the same thing. That is, it’s always through compliance. You know, the masses are controlled, be it the first world war or be it the pandemic. It’s the same situation. We craft our own face in that respect. And if we’re going to buy into the narrative then expect to suffer, attachment is pain. And attachment to the narrative is extreme pain. It doesn’t matter where you are in the sort of hierarchy of the narrative. It’s painful.

I hope you don’t mind the questions about Wally Hope and the organization of Stonehenge Festival? You stated that there’s a strong evidence that Wally didn’t commit suicide… Would you mind sharing a few sentences about how you first got to know him and how the original idea to organize Stonehenge came about?

Well, I first got to know him because I live in an open house and have done since 1968. An Open House being just a place where people will come and go and people do come and go. Anyway, Wally turned up one day, in fact I think he appeared in the kitchen window, the kitchen looks out onto the garden. And I’ve got the usual things happening inside, you know, we were probably a few people sitting around the table and chatting about whatever we were chatting about, films or books was always sort of the dialogue, it was sort of more cultural and political. Anyway, this guy turned up shouting “Wally” and then he disappeared around the corner, one of the out buildings, and then he came back backwards, followed by a snowstorm. I think it was May, it was a beautiful warm day. And anyway he was sort of like, beckoning to something, at first we didn’t see what, and then as he got further into the garden, you know, there was a snowstorm coming down. And he was good at that, he was quite good at magicking weathers and things like that. And then he went back with it, I think he sort of pushed it away and then reappeared. He’d sort of done his show, if you like, but I might point out at this point that I at the time was and never have been into acid or psychedelics or any drugs. I don’t take drugs, short periods of time I smoke grass, but apart from that, not at all. So it wasn’t a drug induced experience. It was just a bit of wild magic going on, which is there if you open your eyes. I mean, it’s actually that magic is nature and nature doing its thing. We’re so far from it, we now see it as magic. But it isn’t magic at all. It’s just what’s happening. Anyway. That’s where I first met him.

“I don’t just believe that he [Wally Hope] was assassinated, I know he was”

He was so charismatic and sort of character prone to some lunatic ideas. Like the Stonehenge festival, I mean I actually never enjoyed festivals anyway, I used to find them rather tedious. He was very keen at this idea because there’d been violence at Windsor, where there had been a festival taking place in Queens gardens. Not a very good place to have a festival. Unless you want to be political. And that’s actually why they were there. Well, what Wally wanted was a place where we could all just go and have fun when I say Wally, I mean, Phil Russel, Wally Hope. And he had this idea that Stonehenge would be the ideal place, he was a bit of a sun worshiper, in a deep sense. You know, the sun was his God. He always used to spend most of the winters in sort of Crete and places like that. Anyway, his idea is to have a festival at Stonehenge. And so that’s what we organised, and by organise IT mean about 100 stoned hippies the first year sitting quite a long way away from the stones and sort of fighting off the local Constabulary. I didn’t go, I didn’t go twice, I just took some bread runs, cooked loafs of bread here and took food down there. So I was part of the organisation, very much a part of the organisation and the promotion, but never actually particularly engaged in it as I don’t particularly enjoy festivals. So that was that.

The death was a very, very, very long story. Anyway yeah, and I mean, I don’t just believe that he was assassinated, I know he was. Something I’ve lived all my life and occasionally get a bit upset about, you know, just in the sense of this sort of sheer brutality of it. Probably you know, which was unnecessary. He was a very kindly, loving guy who got done in for having crazy ideas. It’s not rare, is it?

It must have been very frustrating to see something coming to such a sad ending. Would you say that your involvement with Crass was your mantra or answer, if you like, to what was happening at the time?

Yeah I’ve said that many times. You know. I spent two years after Wally’s death writing a book about investigating it, I conclusively proved he was assassinated by the state. For two years when I was working on it I started getting threats, you know, threats from police and threats from gangland because there were sort of strange gangland ties with it. If you start investigating something like that, it’s like going through the dirty washing, it’s disgusting. It goes on and on and it doesn’t close, you don’t come to something, you get away into this sort of barren desert of horror, you know, and if it wasn’t Brighton gangland or the Essex police and mismatches and another very similar fate occurring to another Wally in Epping Forest about sort of five miles from here, which was equally provable as a takeout, this time possibly by the gangland not by the Essex police. There was this tie between the Essex police and the Brighton gangland at that time anyway, et cetera. It’s all filthy, shitty and mucky. I finished the book, and I took it to a guy who I regarded as a very fine thinker. He actually said, “Well, it’s absolutely perfect, you prove the point. But there’s one thing that’s wrong with it. And that’s it’s too perfect, the plot is too perfect”. He said that, “what you haven’t accounted for is his human mistakes”. Then he said that had there been mistakes in this, then it would be much more believable and acceptable. And I sort of took that to heart.

And then I started thinking I’ve written this book, it was beautifully written and very well investigated. And I thought, well, the result of this is, you know, a Guardian review, you know; “Deep Insight Into Drugs And Rock N Roll” and hippies and blah, blah, blah. And I thought fucking hell, it’s a sort of bourgeoisification of what all that was about, you know, and I’d gone the wrong way. I’d taken the wrong route, you know, producing the book so people can sit in their middle-class homes sort of enjoying reading about a life they never dared even put a finger into.

I realised that all art becomes a part of those conceits, the conceits of inaction, the conceits of passivity. And I was more angry about that. More angry about having fucked about for two years trying to prove something to people aren’t worth proving anything to. And that’s really conjured up a far more sort of revolutionary stance on my behalf, they’re right, if you won’t listen, try a bit of this. And when I mean listen – if you’re not going to try and understand if you’re not going to make any effort at all, and you’re just going to sit on the sidelines, reading about it and getting a bit of sort of vacuous fun from then piss off, have a bit of this, and that was very much where Crass came from. And Crass came out of a relationship between Steve and myself. He was hell of a lot younger than I was, but he was equally pissed off. He was a working-class kid from East of London, utterly nothing on offer to that class of person. Just more drudgery, more drudgery and trenches if we create them. And he knew that but didn’t know how to get out. But he knew about this house also because his brother was a sort of hippie guy who used to come and go. So Steve turned up and we were both really pissed off at the time. And we didn’t start a band. We just started fucking around, making noises really, that became Crass because lots of people come through the house. And they’d say, “Cool, that sounds good. Can we join” and it was sort of like kids playing really, we never had any idea of creating a band and going out on the road or doing that stuff, we were just fucking about. It was never contrived in that way.

“There is no authority but yourself”

Looking back, is there a certain moment, sentence, lyric in Crass that always warms your heart?

Not really. I think it’s just “There Is No Authority But Yourself”. I mean, that warms my heart because it’s absolutely true. It’s irrefutable, it’s the most powerful thing that Crass said. I said, within Crass. If you’re gonna think otherwise, then why not just go jump into a grave? There’s plenty of them around. And most people seem to do that. There is no authority but yourself, who else tells you or can tell you who you are, what you are, why you are? No one can. You don’t even know yourself. So you ask yourself, no one else, what do they know about it? That’s why I didn’t buy into vaccines, for example, not because I object. If people want to take them, that’s their business. But I mean, I wouldn’t touch them with a bargepole. Because I know about my body and I know how to look after it. And it knows how to look after itself. And if that means I die of the pandemic, fine. That’s the way it goes. I mean, we have to live in life, not sort of, I mean, creating sort of all these, either pharmaceutical or cultural, they’re all barriers, you know, to our naked love. And that’s, that’s how I want to see it, I mean, I stand naked in body and mind. I mean, obviously, I’ve got some clothes on at the moment, but effectively. And now I won’t accept any intrusion on that. So, there is no authority but oneself. It says it all really. I mean, you know, it’s a big band who had lots and lots and lots and lots to say, but in the end, what they say is, well, don’t listen to us, listen to yourself. We can give you a few tips, maybe but ultimately, find your own bloody way. There is no way. The only way is your own. Because I mean, that’s actually irrefutable. If you choose to be an idiot, that’s what you’ll become very easily. Most people seem to take that option.

“Poetry makes me”

What currently occupies your life? Are you working on something new?

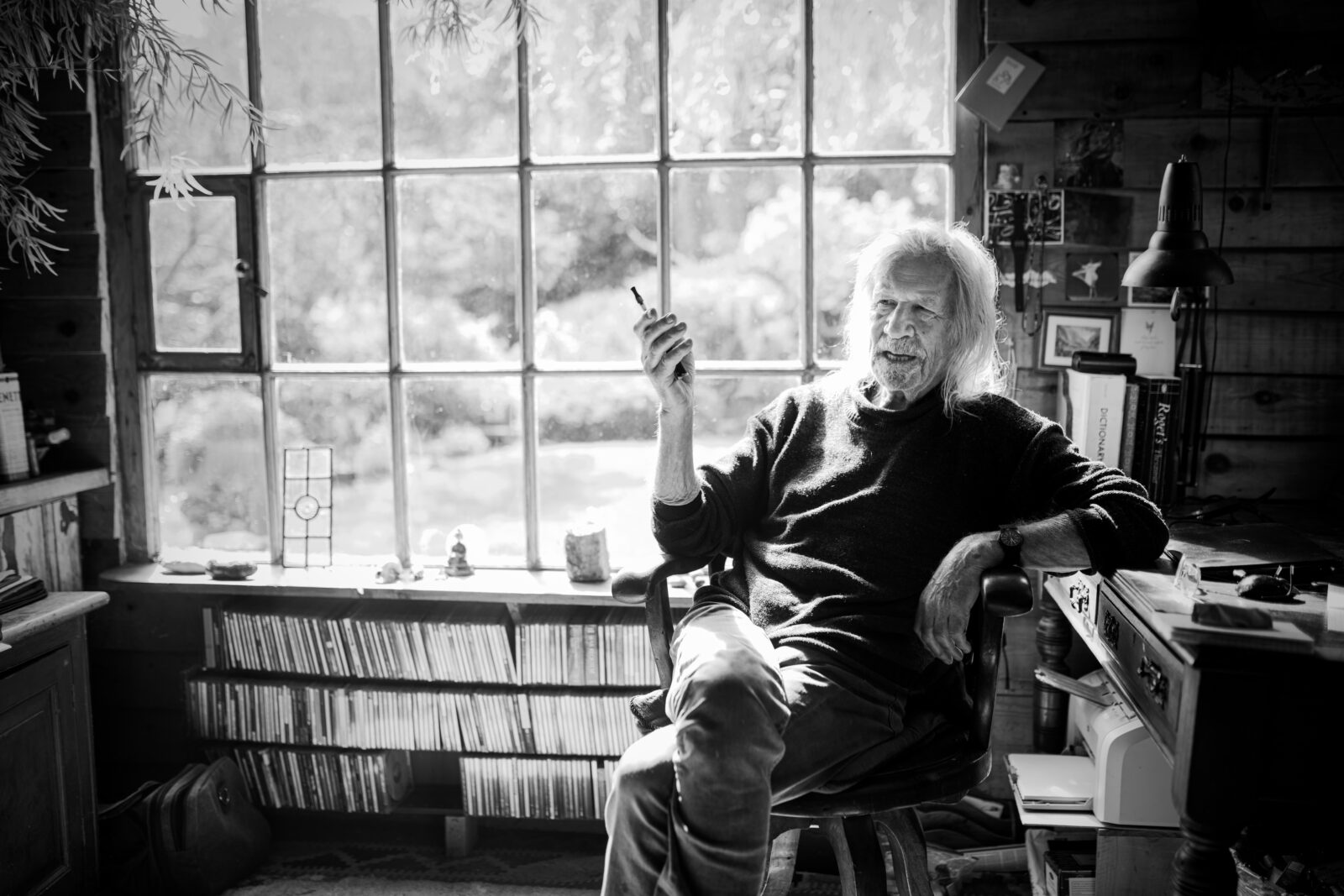

Well, it’s not “currently”, I’m always working on something new. That’s all I ever work on, whether it’s a new loaf of bread, or a new pile of logs for the fire, or whether it’s stroking a cat or writing a poem. I mean, I don’t see any difference between any activity, there isn’t anything which is more important, in that sense I’m not an artist. I don’t want to be an artist. I want to be a person in my own right. Really I don’t see the difference in any of my activities. Whether I’m blowing my nose or trying to find a word of wisdom, or whatever it is, it’s all part of the same story. Or one becomes self-conscious. You get in the way of yourself. So you might as well forget it. It’s like people say, “Well, what are you going to do today?” Well, how the fuck should I know what I’m going to do today. And how I’m going to do it. I’m not interested in what I’m going to do today, I’m even less interested in what I am going to do tomorrow. I find it intrusive. And one of the worst purveyors of that intrusiveness is oneself. One says “What could I do today?” Well, who’s the “I” to want to do anything? You know, find out. Get out of the way and find out what you want to do. Don’t decide what you want to do and do it. And so it’s sort of like trying to develop a sort of fluidity of being which isn’t tied up with progress. Advanced stuff, it’s boring. I find it incredibly boring to have to do anything. I do it because that’s what I find myself doing. I mean, poems come from nowhere, I don’t make up poetry. Poetry makes me. And it’s the same with bread. I don’t make bread, bread makes me. You know in the sense that you know, everything is a reflection of what we ingest. And everything is a reflection of what we inhale and exhale. It’s all the same.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Well, thank you. I think I’d argue that, I think the last word is yours.

Klemen Breznikar

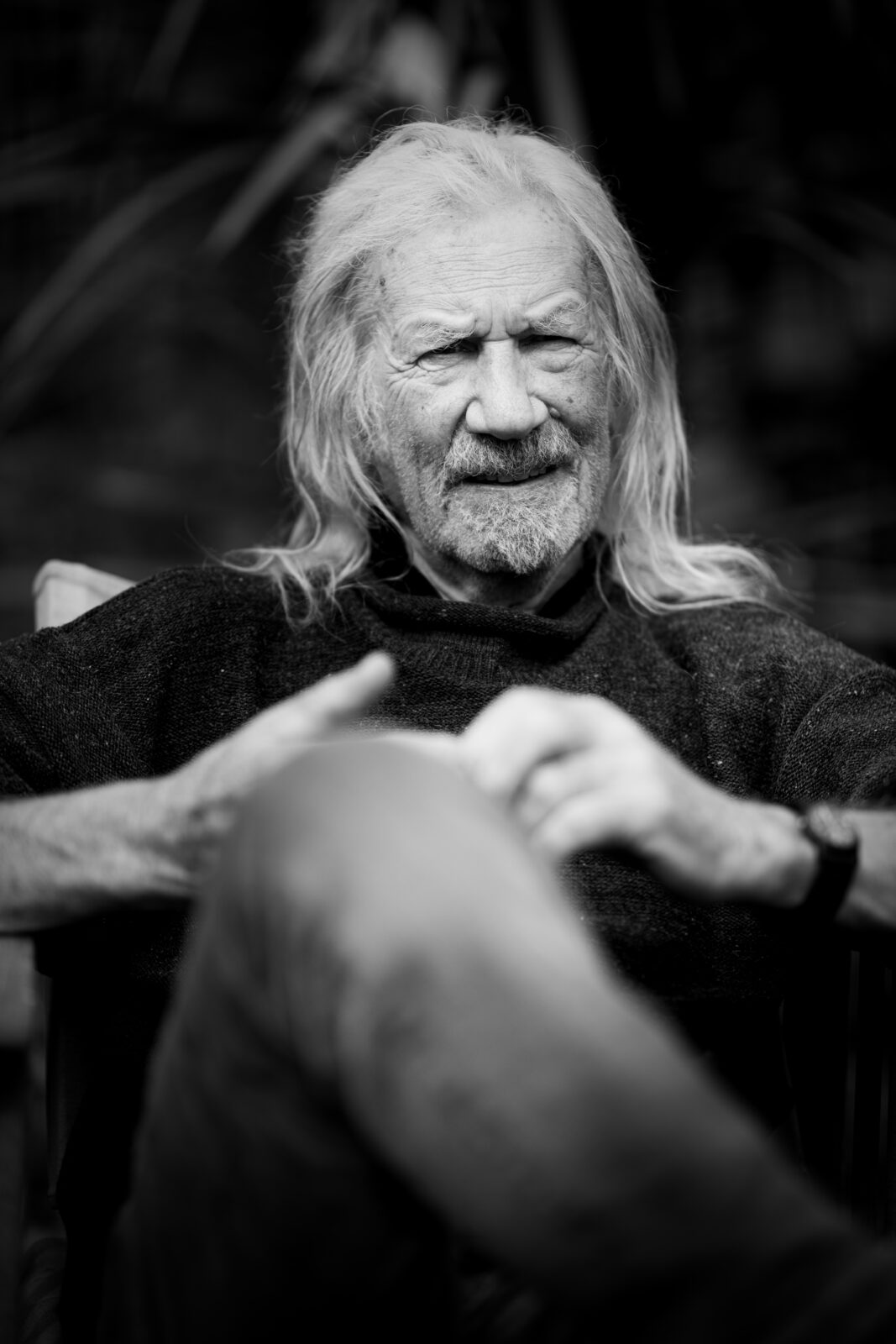

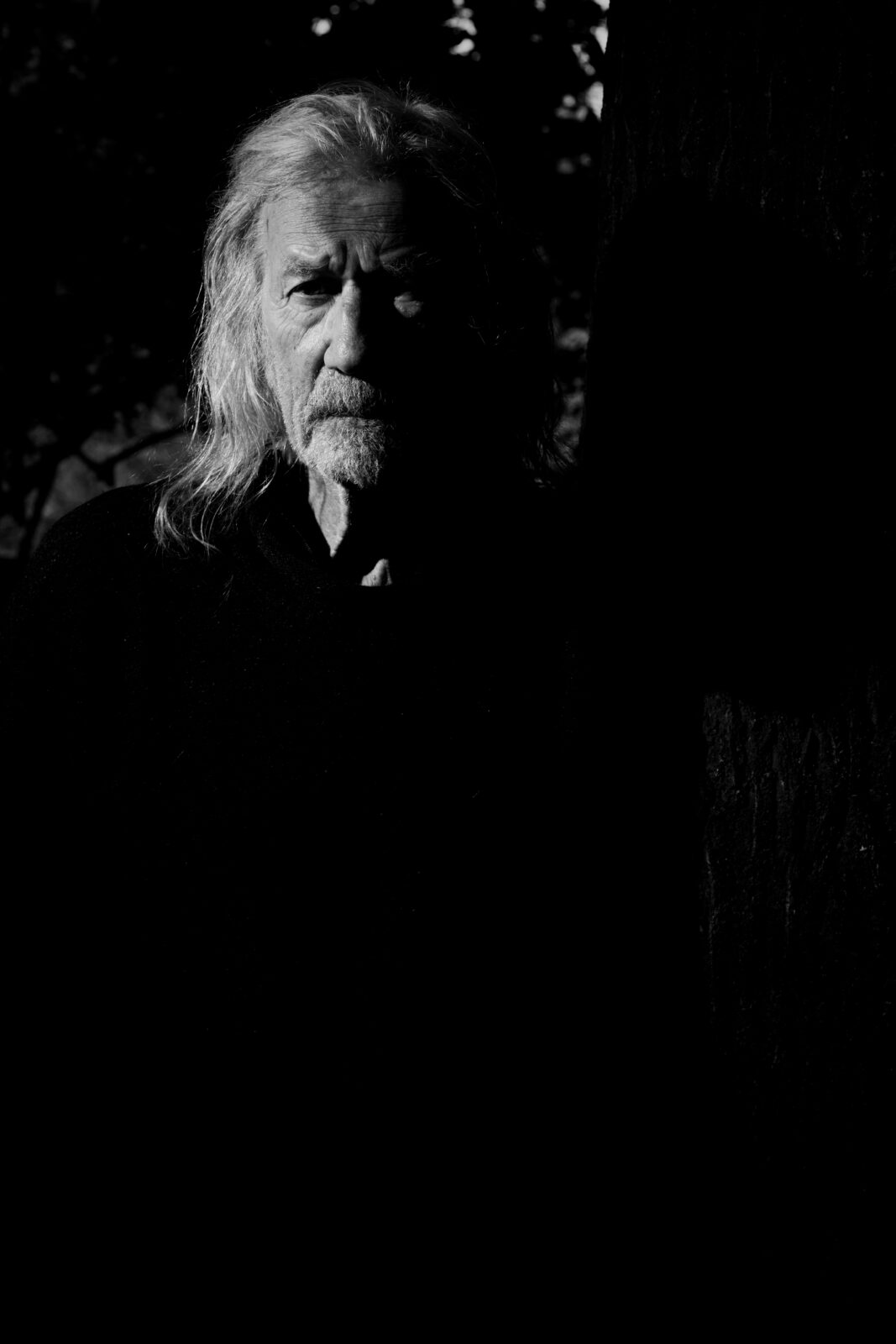

Headline photo: Maryann Morris

Penny Rimbaud Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

Youth Facebook / Instagram / Twitter

One Little Independent Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

An interesting interview. I enjoyed the thought provoking nature of Crass. Was only chatting to some other music mates last week and Steve Ignorant popped into the conversation. Never met Penny as yet but we did on occasion drop a sack of organic long grain brown rice off in North Weald?we were purveyors of wholefood’s on Harlow market at that point. We were also in a band the Darting Tongues our first gig was at Stonehenge free festival and Wally appeared wild dancing at the front of the stage as he was able to materialise as soon as the tunes started zooming through the air?