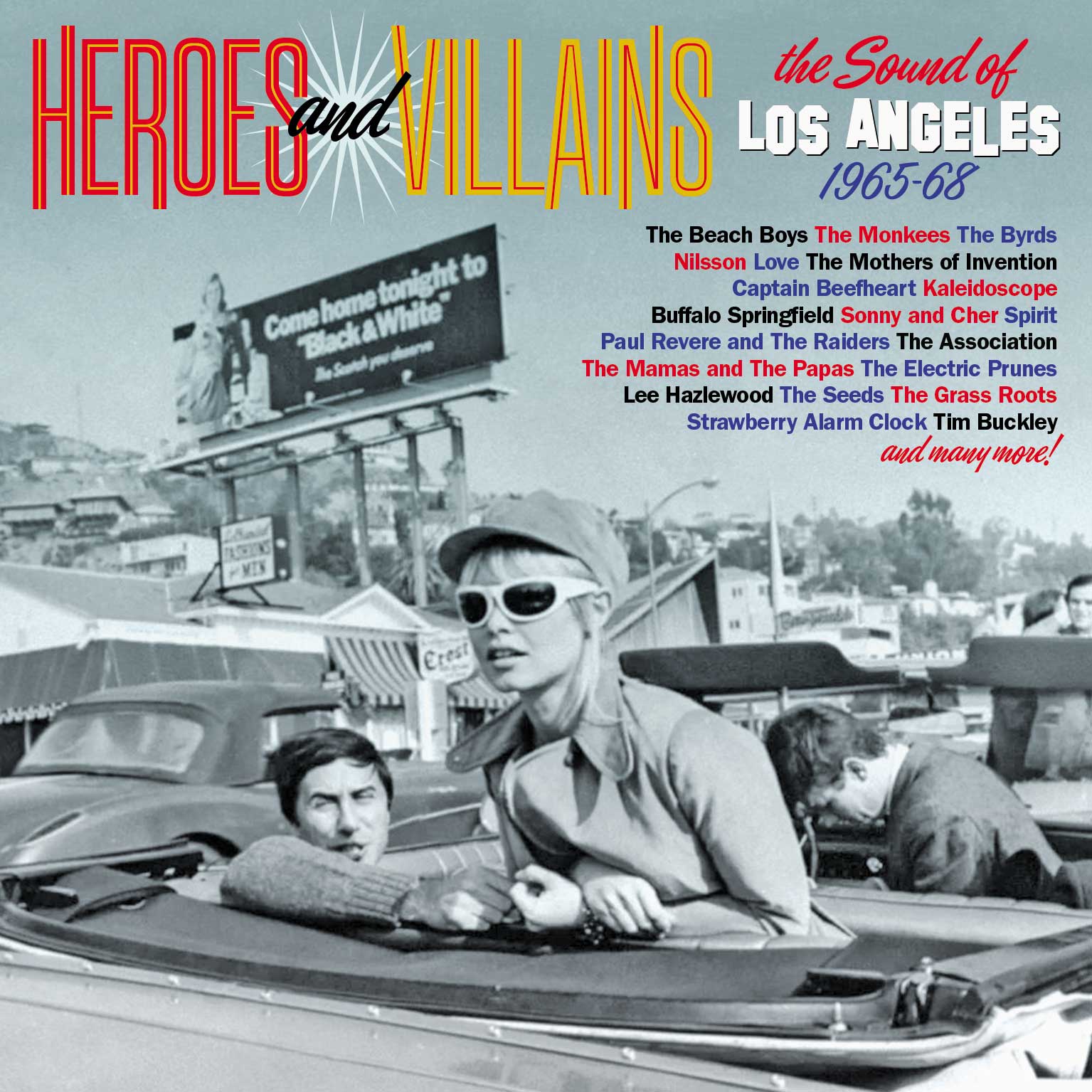

Various Artists – ‘Heroes & Villains – The Sound Of Los Angeles 1965-1968’

“I hate so called ‘surfin’ music,” Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys told 16 Magazine in September 1965. “It’s a name that people slap on any sound from California.”

Such a revelation from the frontman of the group behind such hits as ‘Surfin’ USA’ and ‘I Get Around’ may have been surprising to the contemporaneous readership of 16, but, in truth, the increasingly introspective Wilson had long resented his association with the carefree Californian lifestyle encapsulated in his early music.

The times, after all, we’re-changing; Beatlemania had ignited a renewed excitement in youth culture absent since the genesis of rock and roll, the war in Vietnam was escalating into a bloody fever pitch, the L.A neighbourhood of Watts had burned to the ground in a series of scorching race riots just one month prior, and a nascent counterculture was emerging not just across the West Coast, but all around the globe.

Earlier in the year, Wilson, having suffered a series of breakdowns, announced to his bandmates his decision to withdraw from future tours. Within the same timeframe, he would take L.S.D for the first time- “it just tore my head off,” he would later elaborate, “you just come to grips with what you are, what you can do and can’t do, and learn to face it.”

And so, by the time of Wilson’s repudiation of what much of his music had come to embody, work had already begun on songs that would feature on the next Beach Boys album, the seminal proto-psychedelic ‘Pet Sounds’- a hugely influential LP that would come to be recognised as the increasingly fragile frontman’s bona fide magnum opus and a signpost heralding pop music’s growing sophistication as a genuine art form.

All the while, Los Angeles had stepped out of the shadow of New York and emerged as the United States’ preeminent pop cultural hub. Nowhere was this so obvious as on the singles charts- in 1964, records cut in L.A spent only three weeks at number one, whilst 1965 saw such songs enjoy twenty weeks at the top of the bestseller’s list.

Marrying the influence not only of the Beatles and Bob Dylan but also of surf, garage, folk and protest music, that year saw the emergence of a parade of long-haired, socially conscious acts- the Byrds, Barry McGuire, Sonny and Cher, the Mamas and the Papas- who championed the aesthetics of the embryonic hippie and anti-war movements. “Take me for a trip upon your magic swirling ship” couldn’t have been more of a palpable diversion from “surf city, here we come.”

In the wake of the jingle jangle morning came a veritable migration of musicians, artists and freaks who opted to up sticks and relocate to the Hollywood Hills, in particular fecund mountainous neighbourhood by the name of Laurel Canyon. Located not far from the Sunset Strip and its dazzling array of nocturnal caverns like the Whisky-a-Go-Go and Pandora’s Box, Laurel Canyon became a nexus for countercultural cross-contamination as the movers, shakers and young turks of the new generation collaborated, partied, and, as happened all too often, romantically pursued one another.

A sort of mass artistic serendipity, Neil Young would later recall that he and his like could not exactly pinpoint what force had brought them all together in the Canyon- they “were just going like Lemmings.” It made, nonetheless, for a highly hedonistic scene, presided over by the unofficial dual monarchy of Cass Elliot and Frank Zappa, both of whom maintained open houses that hosted notoriously decadent all-night parties populated by all manner of what Russ Meyer’s controversial 1970 film ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls’ would categorise as “perverts, fruits, swingers and kooks.”

Over the next three years, in the words of David Wells, “L.A erupted into a swirling confusion of Hollywood hucksters, wide-eyed flower children, spoilt Bel-Air brats, caged go-go dancers, pianos in sandpits, love-ins, freak-outs, race and youth riots and quasi-religious cults.”

And, as Wells also observes, it was “not always easy to differentiate between the heroes and villains.” A presiding air of menace lingered over gassy, classy L.A just as potently as the smell of marijuana smoke- as can be detected in recordings from the dawn of what was supposedly the Age of Aquarius.

After all, Love- fronted by the famously volatile Arthur Lee- concluded their punkish acid tirade ‘Seven and Seven Is’ with the sound of an exploding atomic bomb, the Mothers of Invention spoke of how “every day is just another rotten mess” with “no delay” to “that trouble coming every day,” and, perhaps most famously, Buffalo Springfield captured the uneasy tension of the times with their1966 recollection of the Sunset Strip riots, the generational anthem ‘For What It’s Worth’: “paranoia strikes deep.”

All manner of eccentric, sinister and predatory figures prowled the scene. As Joni Mitchell recalls, there was “one guy who had a parrot called ‘Captain Blood” who “was always scrawling real cryptic things on the inside walls of my house.” Then there was Vito Paulekas, a man in his fifties who presided over a harem of predominantly young female ‘freakers’ who flocked to see early gigs by the likes of the Byrds and Love. When Vito’s three-year-old son, Godo- slated to play Lucifer in an upcoming Kenneth Anger film- died after falling through a skylight on December 23rd 1966 whilst, as some repute, under the influence of L.S.D, the group commiserated by hitting the Strip the very same evening and dancing the night away, as per usual.

Most infamously of all, 1968 saw Beach Boy Dennis Wilson boast to Record Mirror Magazine that he shared his home with “17 girls.” As is well recorded now, the pseudo-commune led by whom he referred contemporaneously to as ‘The Wizard’ in fact comprised Charles Manson and his ‘Family’ who, one year later, would bring Los Angeles’ apocryphal ‘Sixties’ to an apocalyptic and bloody end when they visited the horror of ‘Helter Skelter’ in an August swelter onto the canyon with the horrific Tate-LaBianca murders.

The Family’s gory fingerprints inexorably stained the Los Angeles hippie scene- not only had the Beach Boys recorded and released one of Manson’s songs, ‘Cease to Exist’ (retitled ‘Never Learn Not To Love’), but the Family had also rubbed shoulders with many of the most prominent figures in the local music industry.

Family associate and eventual convicted murderer of Gary Hinman, Bobby Beausoleil, had performed with an early iteration of Love, and mogul Terry Melcher had expressed some early interest in recording what would later be dubbed the ‘love and terror cult’, even granting them an audition at their Spahn Ranchheadquarters in 1968.

As Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas would recount, “before 1969, my memories were of nothing but fun and excitement… the Manson murders ruined the L.A music scene. That was the nail in the coffin of the freewheeling, let’s get high, everybody’s welcome, come on in, sit right down. Everyone was terrified. I carried a gun in my purse. And I never invited anybody over to my house again.”

Beyond morbid curiosity value, it is this heart of darkness which perhaps led to Los Angeles’ eventual retrospective overshadowing the outwardly more blissed-out San Francisco Haight-Ashbury scene, but it also seemingly contributed to the creative context that has made the music so timeless. Indeed, between 1965 and 1968, the mondo mod wonderland of Los Angeles bequeathed the world with some of the most critically renowned records of any era.

It is this time and place which Grapefruit Records have come to cast their omnipotent eye on with their recent release, ‘Heroes and Villains: The Sound of Los Angeles 1965-68.’ Boasting 90 tracks over 3 discs and accompanied by a revealing 80-page booklet with a 20,000-word annotation courtesy of David Wells, the four hours of music that makes up this set provides a near definitive aural tapestry of the magic and mayhem percolating through the L.A music scene in the latter half of the 1960s.

There’s no shortage of hits- the Monkees’ scathing riposte against the apathetic “status symbol land” of suburban America, ‘Pleasant Valley Sunday’ kicks off the set, which also features high charting songs by Paul Revere and the Raiders (‘Kicks’), the Association (‘Along Comes Mary’), the Mamas and the Papas (‘Twelve Thirty’), the Grass Roots (‘Let’s Live for Today’) and the Parade (‘Sunshine Girl’).

Meanwhile, other major players on the scene, such as the Byrds, Sonny and Cher, Lee Hazlewood and the Strawberry Alarm Clock, are represented by lesser compiled cuts from their discographies (an alternative version of ‘Why’, ‘But You’re Mine,’ ‘Sand’ and ‘Sit With The Guru’, respectively), and just about every major act from Buffalo Springfield to the ill-fated Bobby Fuller Four is represented in some shape or form-in a licencing coup, the box set even features the first official various artist compilation appearance by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention with idiosyncratic Disc Two opener, ‘Hungry Freaks, Daddy.’

Stylistically, the material here careens playfully between genres that seem to seamlessly flow into one another, with jagged blues rock like ‘Zig Zag Wanderer’ by Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band easily sharing disc space with tongue and cheek melodic vaudeville like Nilsson’s ‘Mr Richland’s Favourite Song’ and the downright weird pocket symphony of the Beach Boys’ ‘Do You Like Worms (Roll Plymouth Rock).’

Elsewhere, there’s proto country rock such as ‘Luxury Liner’ by the International Submarine Band, early singer-songwriter introspection from Tim Buckley (‘Carnival Song’), Eastern raga pop like ‘Isha’ by Chris and Craig, chugging Who-style mod pop (‘Uncle Jack’ by Spirit) and plaintive folk rock from the Rose Garden (‘Long Time’). For every familiar cult name- the Seeds, Sagittarius, the Millennium, the Misunderstood, the Electric Prunes, the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band- there’s a litany of names so obscure that even the most ardent of crate diggers will be left scratching their heads- ‘Children of the Mushroom’ or ‘The No-Nâ-Mees,’ anyone?

It is this level of musical archaeology that has always been Grapefruit’s strong suit, and in this respect, ‘Heroes and Villains’ does not disappoint. Some of the best and most intriguing music here comes from the realm of the totally forgotten, from cynical cash in one-shots, teenage Beatle wannabes, proselytising folkies, earnest adherents to the psychedelic revolution and beatniks out to make it rich.

Such groups often show an endearing adherence to the vogueish trends of the British Invasion- just take the Churchill Downs and Jim and the Lords- whilst some of the stand-out moments of the entire set come thanks to exhumed household non-names- from the slick guitar and keyboard interplay and tight harmonies on ‘Tomorrow’s Girl’ by Merrell and the ‘Xiles and the chiming resentment of ‘The Music Scene’ by Fapardokly, to the retro-futurism of ‘Computer Girl’ by Urban Renewal Project and the mystic moodiness of the post-nuclear ‘Fire Engine Sky’ by Michael Blodgett, no stone is left unturned.

A number- the Satans, the Prophets of Old, the Heros, the Odds and Ends and Somebody’s Chyldren (the latter a garage rock band who backed Mae West on her mid-60s albums whilst possessing an average age of fourteen at the time of recording) contribute songs that make their inaugural appearances on a legitimate compilation, with compiler David Wells wryly noting in his introductory essay that “one or two are so rare that the bands didn’t know they’d been issued until we contacted them.” Two recordings, ‘Run’ by the Candy Company and ‘Summer Magic’ by the Paper Fortress, are so rare as to have never been issued until now.

Perhaps the only glaring omission, most likely as a result of copyright issues, is the absence of any material from the Doors, the band who perhaps best embodied the souring mood of the end of the Sixties with their ominous odes to the “bloody red sun of fantastic L.A”- but anyone with even a passing interest in 1960s West Coast music is likely already heavily familiar with the output of Mr Morrison and co, so their non-appearance does little to impede the flow of this otherwise excellent set.

Nonetheless, by the mid-1970s, the Lizard King’s assertion that “no one here gets out alive” seemed all too prophetic. Strip scenesters like Gram Parsons, Cass Elliot and even Jim Morrison himself were long gone, with many of the foundational bands of the scene having already disbanded. A new zeitgeist- not to mention new narcotics, chiefly a particularly prevalent white powder- began to take hold, relegating the golden era of psychedelic L.A to the past as the laid-back post-hippie country rock of the Eagles, the Flying Burrito Brothers and Jackson Browne replaced the feverishly frenetic go-go backbeat that once propelled Tinseltown to the top of the pops.

But, Grapefruit’s stellar new box set does much to resurrect those weird scenes from within the goldmine between 1965 and 1968, recontextualising the familiar into but one feather in a peacock’s plumage. By the time Disc Three fades out with ‘Hippy Town’ by Georgy and the Velvet Illusions, it’s as though the mod mania of the swinging Sunset Strip never buckled to Manson’s madness- as Z Man would no doubt triumphantly proclaim, “this is my happening, and it freaks me out!”

Jack Hopkin

‘Heroes and Villains: The Sound of Los Angeles 1965-68’ (Grapefruit Records)