Yochk’O Seffer | Interview | ZAO

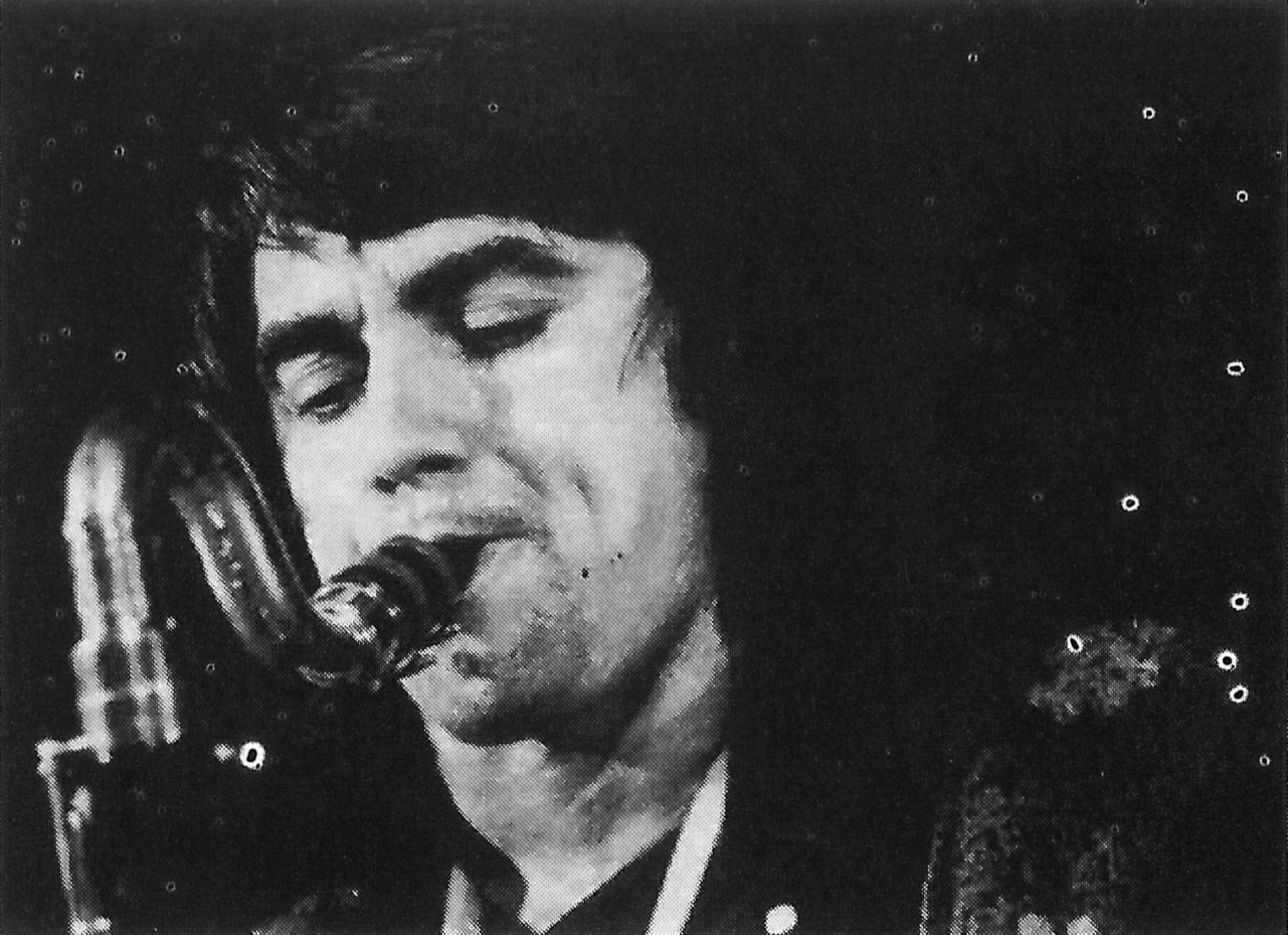

Yochk’O Seffer is a legendary composer and instrumentalist of Hungarian origin. Seffer is also an active painter and sculptor. Master saxophonist and pianist, his main inspiration is Béla Bartók and John Coltrane.

Yochk’O Seffer was born on July 10, 1939, in Miskolc (Hungary), and arrived in France in 1956. He studied harmony and musical analysis with Nadia Boulanger, then the saxophone as a pupil of Marcel Mule from 1959 to 1962. He then studied at the Beaux-Arts from 1962 to 1964.

“Letting yourself be carried away by the cadence of a language that you don’t understand”

Would you like to talk a bit about your background? Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

Yochk’O Seffer: I was born in July 1939 in Miskolcz, a Hungarian town less than a hundred kilometers from the Soviet border. In other words, as my biographer says, “in the wrong place at the wrong time”. Art has had a significant place in my family. My mother was an art teacher and my father played as a clarinetist at the city theatre. In addition, in front of my parents’ house, from six o’clock to midnight, every Summer, there was Hungarian Gypsy music. Imagine ten manouches with violin, cimbalom, double bass, bratcha. We sat with the whole family on the balcony to listen. I was raised on the sound of the violin. It got me into music and made me “in love” with the strings.

You are a classically trained musician. What attracted you the most in saxophone and the piano?

My grandfather and father played the clarinet. My father thought he was doing the right thing by making me learn it. Of course, he didn’t want me to make it my job. He just thought it would bring me righteousness, morality. My first instrument was therefore the clarinet. I quickly took classical piano lessons with an old teacher, career soldier, friend of my father. He wasn’t a soldier for nothing. He was very, very rigid. One day, my left hand wasn’t working very well in a Bach composition. He said to me: “Once will be fine. But pay attention to the second…”. The second time…same! He was furious that I did not follow his observations. He tapped my fingers with a ruler. He hurt me horribly. When I was 10, I enrolled alone at the Miskolc Conservatory. They only let in motivated people. I studied Czerny, then Bach. The days were busy. In the morning, from nine to one o’clock, I took lessons in clarinet, music theory, music history and in particular Hungarian folklore. We studied according to the Kodaly/Bartók method. This method was based on the practice of singing a cappella with four voices, the practice of the piano (push ten fingers into a piano does a lot of good to the musicians and we should systematically demand it), and finally the music history and in particular Hungarian folklore. It is only after having worked on these three materials that a musician could choose his path (instrument, vocals, et cetera). I finally got my clarinet diploma. Then I heard a friend of my father playing the tenor saxophone and I started playing it. I had a tenor saxophone. He almost touched the ground. Spectators asked us for the pieces they wanted to hear and paid us by putting tickets in the saxophone pavilion. I remember the hundred forint bills, they were red. Sometimes we earned 7 or 800 forints which represented 15 days’ worth of food. So you could say that the saxophone was the first instrument I really wanted to play.

What was the reason to move from Hungary to France back in 1956?

During the riots of 1956, I saw horrors that a teenager should not see. My brother and I were then caught in a gunfight and we miraculously got away with it. Once at home, when everything was over, my knees began to shake. It was too much and I decided to take advantage of the chaos to realize my old dream: to leave for France. Like every evening, I got ready for the family meal, gave a vague excuse to leave the table and I left the apartment on the sly, my clarinet as my only luggage. After many adventures I arrived in Austria where I was asked to choose a host country. I chose France which made me dream so much.

It must have been a struggle at the beginning in France?

I was welcomed by an uncle who owned a metal parts factory. He was very nice but with him you had to work. However, he understood that music was important to me and he called local musicians to get me to play with them… outside of working hours, of course. But one day I was no longer satisfied with it and I left for Paris with 200 francs in my pocket and my clarinet. It was difficult there. I spent several months in the street, living on the charity of certain prostitutes and I had several cases with the constabulary. France was in the middle of the Algerian war and the police were very suspicious of foreigners. Finally I got the status of political refugee, I met a couple of benefactors who took me under their wing and everything went much better.

How did you get in touch with Marcel Mule and how much did you learn under his wing?

The couple who hosted me were kind to Marcel Mule and allowed me to take his classes and get a scholarship. After a year of preparation with Marcel Jost, and despite the poor quality of my instrument at the time, I was deemed worthy of following Marcel Mule’s lessons, place Dancourt in Pigalle, with Henri Selmer where I got to know the whole Selmer family. Our friendship has never stopped since. Mr. Mule was a magnificent saxophonist, with breathtaking detached, great musicality, but I had trouble playing the pieces I was asked to play. Especially since at the same time I was discovering jazz and contemporary music. After a few years I left his course, even though I respected him a lot and he tried to hold me back.

“The release of ‘Something Else’ by Ornette Coleman was a new trigger for me and I never left this music again”

When did you first get in touch with the music of artists such as Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman and what in particular did you find interesting in their playing?

A record store located near the Luxembourg Gardens made me listen to a record by Art Blakey and Thelonious Monk. I became crazy. I didn’t understand a thing and yet I was overwhelmed. It was like letting yourself be carried away by the cadence of a language that you don’t understand and whose phrasing nevertheless seduces you. Little by little, I dissected and analyzed the phrasings, the chords, the playing of the instruments, and the arrangements. Some say that you have to know the basics in order to gradually appreciate any art form. It’s possible…but I’m not. I discovered “quirks” without caring whether I was dealing with a C 7th, 9th or 13th. I was just like, “this music is terrible and I like it”. During the famous Olympia concert on March 20, 1960, I was in 4th row and the atmosphere on stage was strange. John Coltrane had already almost left Miles Davis to fly on his own. They must have been angry. One entered the stage, the other left. I remember at one point Miles Davis completed a solo and walked away. John Coltrane was hardly at the curtain when the public howled and whistled at him. He hadn’t played a note… This audience was really made up of a majority of “freaks”, that’s the only word that fits. Me, in any case, I loved it and I have never forgotten. The release of ‘Something Else’ by Ornette Coleman was a new trigger for me and I never left this music again.

Music is not your only love as you’re also a painter and sculptor. Where did you learn your craft and what are some of the main topics of interest when it comes to art?

My mother had taught drawing before stopping to take care of me. She put the colored pencils in my hand but the taste for drawing did not come to me spontaneously. My friends were tapping on the window and asking me to go and play a game. My mother had to run after me, threatening with a huge wooden spatula to force me to draw. She wanted me to create cars with colored pencils. And in the end, she was right. Drawing and painting have since been as important to me as music. For me, these disciplines are inseparable, they run parallel like two railway tracks. In sculpture, my idols were Giacometti and especially Henry Moore. Once in Paris, I often went to the museum, to all the museums, to see both modern works and works from the Middle Ages.

Tell us about those early exhibitions you had in the sixties. What were some of the projects that stayed close to your heart? Tell us about the first exhibits you had in the 1960s…

From 1965 I did not stop exhibiting. My first exhibition took place in Bar-sur-Aube, at the priory of Silvarouvre, at the home of a Yugoslav, a very nice guy. A year later, it was the Milan Biennale and the “Sacred Art” exhibition in Paris. During the next edition of this event, in 1968, I shared the poster with Vasarely and Rouault and I no longer stopped the exhibitions, whether in painting or sculpture.

“Everything wanderer”

Would it be possible to draw parallels between painting and music? Would you say that multidisciplinary plays an important role in your life? To make a synthesis of the three arts of sculpture, painting and music?

This period of the sixties reinforced me in my passion for painting and sculpture, which I put on the same level as music. The problem is that many people who work in several disciplines are not appreciated. Me, I am attracted and curious about what moves. I’m a “everything wanderer”. I cannot restrict myself to a single style, or even a single art. However, I do not confuse these disciplines. I respect each of their techniques but I need all of them: I only realize myself in all of them. There is no difference in structuring one’s thought in painting and in music: it is only a question of technique. And once the technique is acquired, you erase everything and you finally make Art.

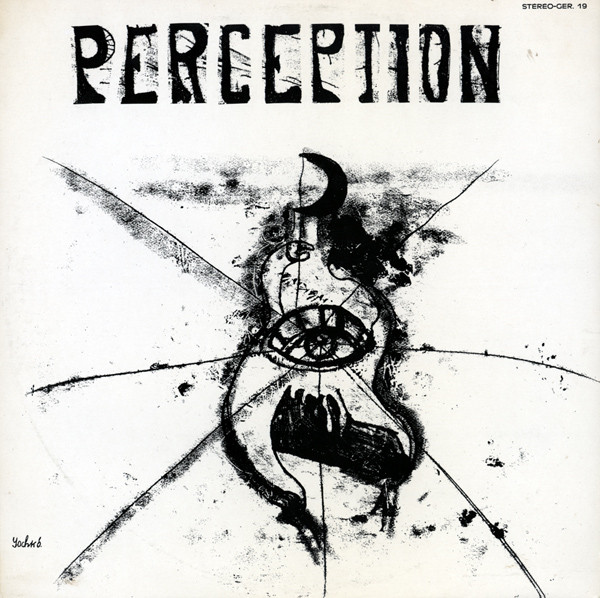

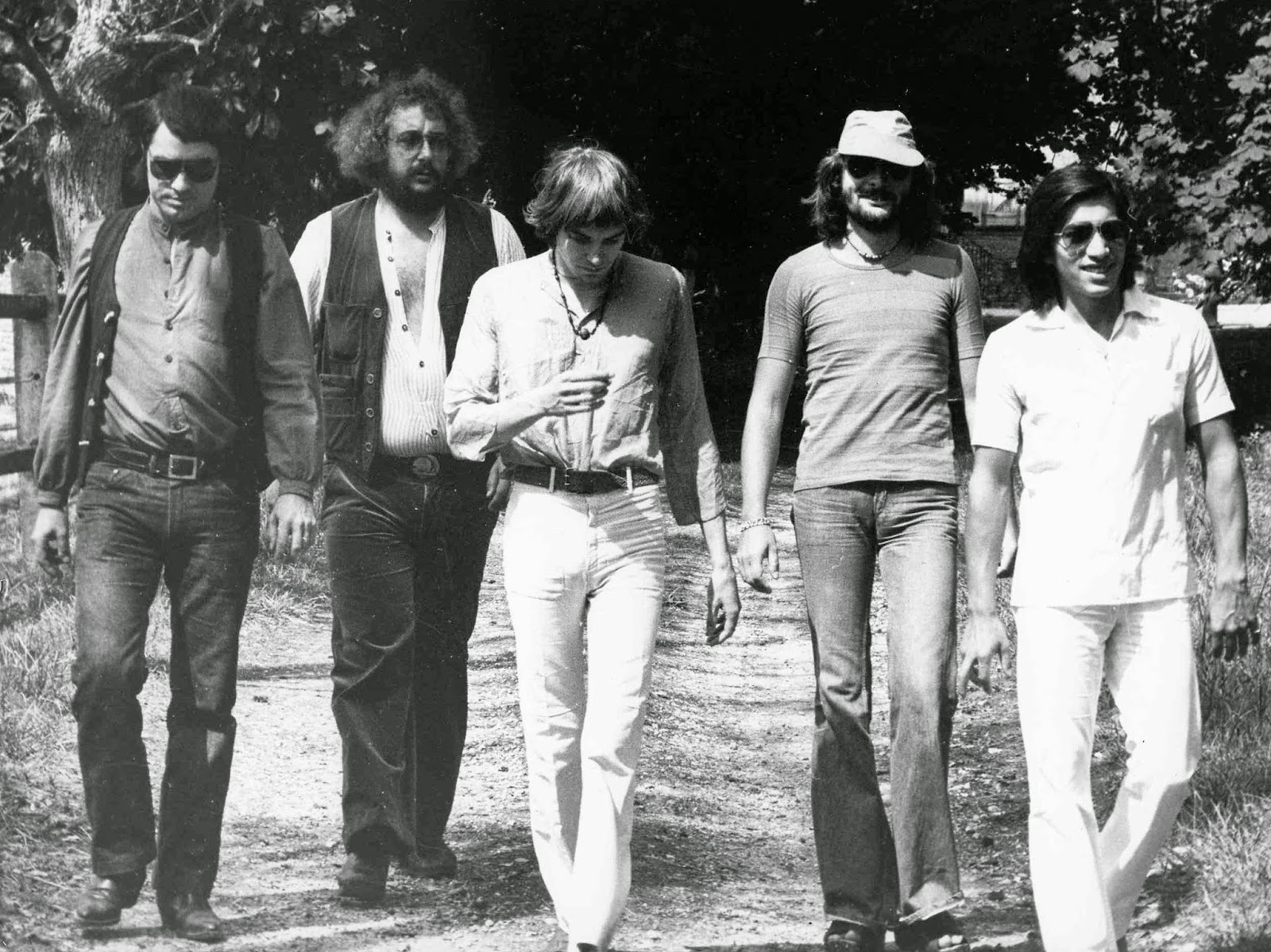

From 1963 to 1968 you played in Eddy Mitchell’s orchestra mainly with Michel Gaucher and Louis Toesca (forming the brass trio) before forming the free-jazz group Perception with Didier Levallet, Siegfried Kessler and Jean-My Truong. What was it like to be part of the orchestra?

Eddy Mitchell was reassembling a group after the end of his famous Black Socks. I really enjoyed this period. We were playing elegant rock and roll which I liked. We were dressed like princes. We were the bourgeois of rock and roll! Eddy had a good sense of rhythm and knew how to capitalize on his vocal specificities. The years spent with him were nothing but fun. He was also very friendly. He didn’t have a big head like some successful singers of the time. He never made us feel like he was the boss. The team was good musically and perfect humanly. We were all friends, and I remember bickering like kids.

When you started to play with smaller groups, especially free jazz, it must have been a completely different (may I say freeing) experience?

That’s for sure! Even though I loved playing in Eddy Mitchell’s band, I longed for something else. Meetings with Didier Levallet on the one hand and Christian Vander on the other hand were decisive for me. I wanted to go towards free but structured music. The Perception years were magnificent. I truly became a jazz musician with Perception: we were in wastelands, attracted by the smell of freedom and danger.

Everyone brought their own compositions. It was at this time that I started to really use the traditional music of my country. I was able to work in a collective context pushed to the extreme and we re-invent the repertoire at each concert..

What was it like when you first met Christian Vander?

I met Christian Vander regularly at Gill’s Club in 1967, when in 1969 I heard him with Faton Cahen and this group which would become Magma I was overwhelmed. He called me for a few food sessions then when Paco Charlery, Richard Raux and Claude Engel left Magma, he asked me to join them.

“Magma was not the dictatorial group that some people like to portray”

Did you enjoy the early years of Magma? How was the creative process for you? Did you have your own freedom or was it more directed by Vander himself?

Magma was not the dictatorial group that some like to portray. Admittedly, Christian was looking to get his music played, he influenced us a lot and I “caught” a lot of things from him. He had a lot of intuition, and was technically phenomenal, but all the musicians gave their opinion and some also composed. Christian let them submit their songs. He was quite athletic that way. It must nevertheless be recognized that he did not need anyone to compose. He was so packed with music that he could have written three times as much as needed for Magma. The music was however very written, and left little room for improvisation, I regularly played Magma at Perception: I needed these two antinomic aspects of music: structure and improvisation. However, at some point, I said to myself that even if serving the music of others was a good thing, it was time that I thought about giving life to the one I carried within me. One evening, Francis Moze, Teddy Lasry, “Faton” and I went to find Christian after a concert to tell him that we were leaving the band. All. Replacing a pianist at short notice is not an easy thing, so Faton stayed another three months so that Magma could meet his commitments. Previously, we had both decided to set up “our” formation: Zao.

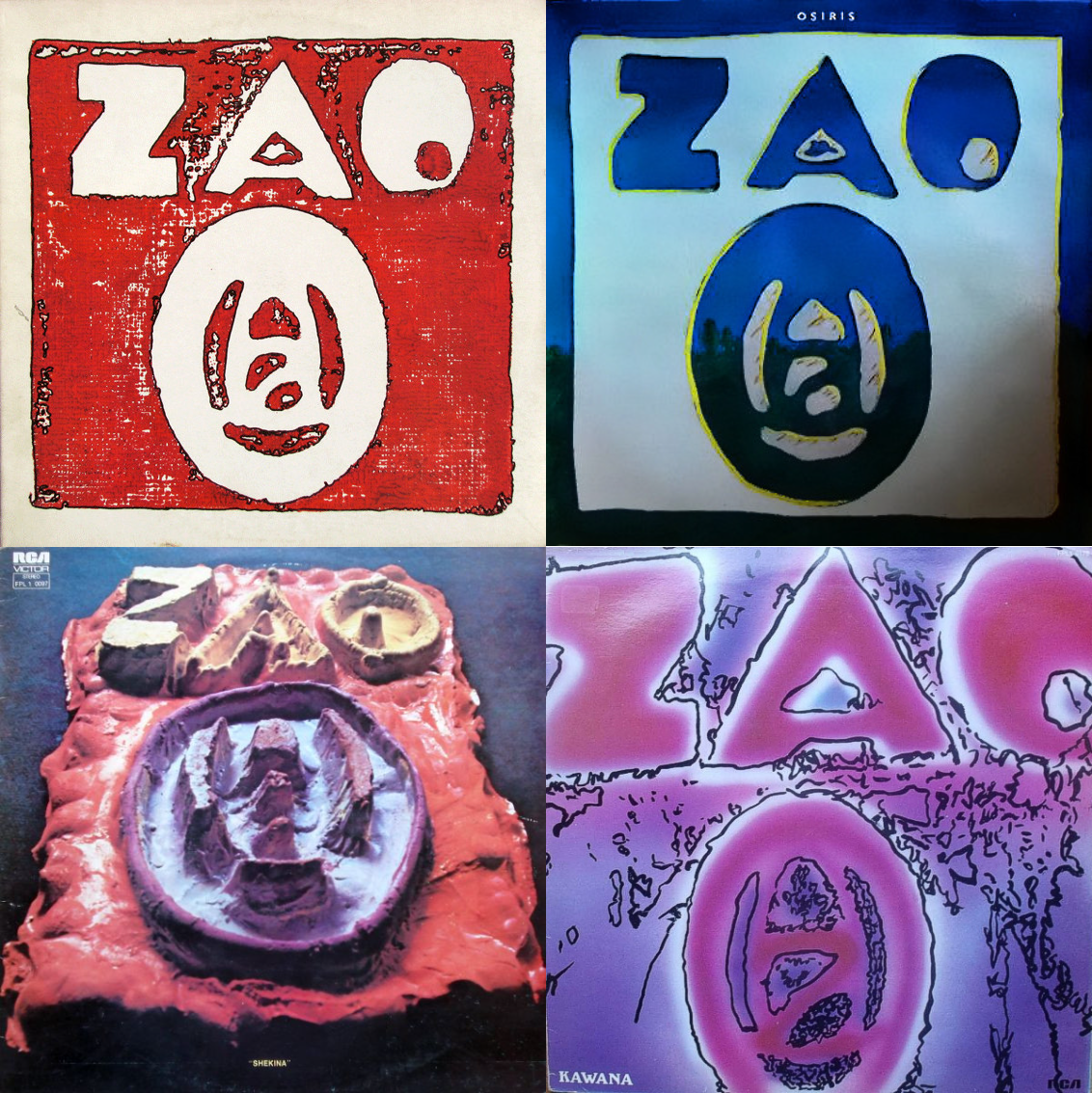

With Faton Cahen, you left the band and formed Zao. The undertone of Magma was still present, but you gave a more improvised touch to the whole experience. Would you like to share some of the best memories of recording albums such as ‘Z=7L’, ‘Osiris’, ‘Shekina’ and ‘Kawana’?

It is very difficult to choose. We were a real bunch of friends and we reinvent ourselves with each recording. I can not tell.

Was there a concept present in your albums?

There was no real concept, except freedom which took precedence over everything. The first two recordings could still be associated with Magma with plenty of room for improvisation, but ‘Shekina’ with its string quartets and ‘Kawana’ and its unbridled jazz-rock were very different.

Speed Limit is another group I would really appreciate if you can share some words about it?

The Speed Limit discs were more discographic hits than a real musical approach. We wanted, all things considered, to rediscover a bit of the spirit of ‘Bitches Brew’ by Miles Davis. In the end, it was something fun to play but didn’t really impress me. I know I’m very strict with these recordings, which a lot of people really appreciate. People often talk to me about ‘Pastoral Idyl’, the recording of which I don’t find very good. On the other hand, Jannick Top played very well there. In those years, the musicians mixed quite a lot. He was between two commitments and he came to play with us and how!

You were also the sole leader of Neffesh Music, a formation that allowed you to extend your experience with the string quartet.

Neffesh-Music corresponds for me to the meeting of three musical directions: first an energetic music, attached to the ground in the sense that it draws energy from the earth to propel it elsewhere; then a music represented by the strings and which could be defined as a legacy of the classical line without forgetting the contemporary contributions; finally, the mystical aspect of music, that is to say the vehicle of an inner journey to discover the universal. Neffesh-Music is the search for the synthesis of these three complementary forms through my own accent.

I wanted to deepen the work started on ‘Shekina’ and rediscover my Hungarian roots. It was a second “birth”. We did three albums and countless gigs, including an incredible tour of the US with Bill Laswell on bass and a memorable gig at CBGB, a wild punk venue. The formation changed regularly between 1977 and 1980, but not its spirit. Then I wanted to move on. I nevertheless reactivated Neffesh-Music in 2008 with a cello quartet and a DJ, in 2019 with a string trio and I will soon record a new album with three cellos and a violin.

At the end of the seventies you became interested in big jazz bands. Did that reflect your original start?

In fact, it’s more of the early 70s… I participated in 4 big bands with Sonny Gray (there were 25 of us and we played “La Bohème” every Friday and that’s where I met Judith moreover), Claude Cagnasso (every Monday at the Théâtre Mouffetard), Yvan Jullien for replacements and Ambrose Jackson. I really learned the trade, bebop, swing, articulation, coordination with the other brass instruments.

What can you say about “soundpainting technique”?

Actually not much. It got a lot better with the mics hooked up to the instruments. I’m not a big sound technician.

It’s a very interesting way to drive music. It’s pretty instinctive. I’ve done things I wouldn’t have done otherwise. Like blackmailing the phone book to a Russian singer, or the recipe for cabbage coulibiac. I had presented a project for the national jazz orchestra where soundpainting would have been conducted by kendokas. Needless to say, the project was not accepted.

So many projects followed. What are some of your albums and collaborations that you’re most proud of?

‘Shekina’, ‘Ghilgoul’, the CD with Christian Vander and the Camerata Chamber Orchestra (“String orchestra”), ‘Prototype’.

“A teacher must know how to let his students “take the plunge”.”

How do you enjoy teaching others?

Before answering the question, I must specify that for me the stage and high-level teaching are not contradictory. I quickly led saxophone courses and then I wanted to broaden my experience to the world of the conservatory, while giving students the benefit of my Hungarian experience. In Hungary, musical education was taken very seriously, far from the laxity and carelessness that then reigned in France. One could only begin to study an instrument after having acquired a piano culture, and that was logical. The piano makes it possible to have harmony before the eyes and in the ears. How do you want to acquire the slightest notion of harmony with a simple saxophone? I preferred to take care of confirmed students who had already practiced for five or six years. I did not have the qualities to teach beginners. This allowed me to effectively transmit my experience of the stage to musicians who had a little “bottle” and therefore could take full advantage of it. I also wanted to not show everything, direct everything. A teacher must know how to let his students “take the plunge”.

I taught based on standards, pieces by Monk, Coltrane or Zao. The standards are “practical” in that they allow you to learn how to play before moving on to something else. I had to ignore my personal work. It would have been very complicated to play on Neffesh-Music arrangements where the spirit takes precedence over the musical material. In 2002 I stopped because I felt that I had reached the end of something.

How would you compare your older material to the latest projects?

I am more flexible, less “snoring”, more elegant. A good example: ‘Zohar’ with ZAO is very square. With a Japanese string quartet in 2004, it was more intimate, more interior…

Would you like to comment on your playing technique? Give us some insights on developing your technique.

I wanted to free myself from the imprint of tonality to move towards pentatonic, then the acoustic scale of Bartók and finally serialism. Then I mixed it all together, sometimes even within the same piece. But I won’t hide from you that serial improvisation is very difficult…

What are some of the latest projects that occupy your life?

A classical music CD has just been released with works by Debussy, Bartók, Kodaly and which ends with one of my compositions played by a violin, cello and piano trio. At the start of the school year, ‘ElektroFar’ will be released, halfway between contemporary music and jazz. It’s a kind of concerto for robot-percussionists programmed by François Causse, my old accomplice. There is a 5-CD set made up of archives and never-released recordings and the Neffesh-Music CD I was talking about above.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

Unsurprisingly, John Coltrane who gave himself maximum freedom in the modality.

Your finest moment in music?

There are two. The first in a Perception concert in Saarbrücken. We were so good. I put my saxophone on the floor and Siggy [Siegfried Kessler] got up and we hugged. The second is when we performed Coltrane’s ‘Offering’ with Christian Vander. We didn’t pretend. We were in it, completely… Together!

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo by Christian Berthier

Special thanks to Jean-Jacques Leca and SouffleContinu Records for making this possible.

Yochk’O Seffer Official Website / Facebook / Instagram

SouffleContinu Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

Thank you for this very interesting interview. I have seen Zao in concert mid 70’s at the Bordeaux Faculty, and it was formidable, great band, great music. I m still are a Magma fan, posecialy the beginning.