Raw Green Rust

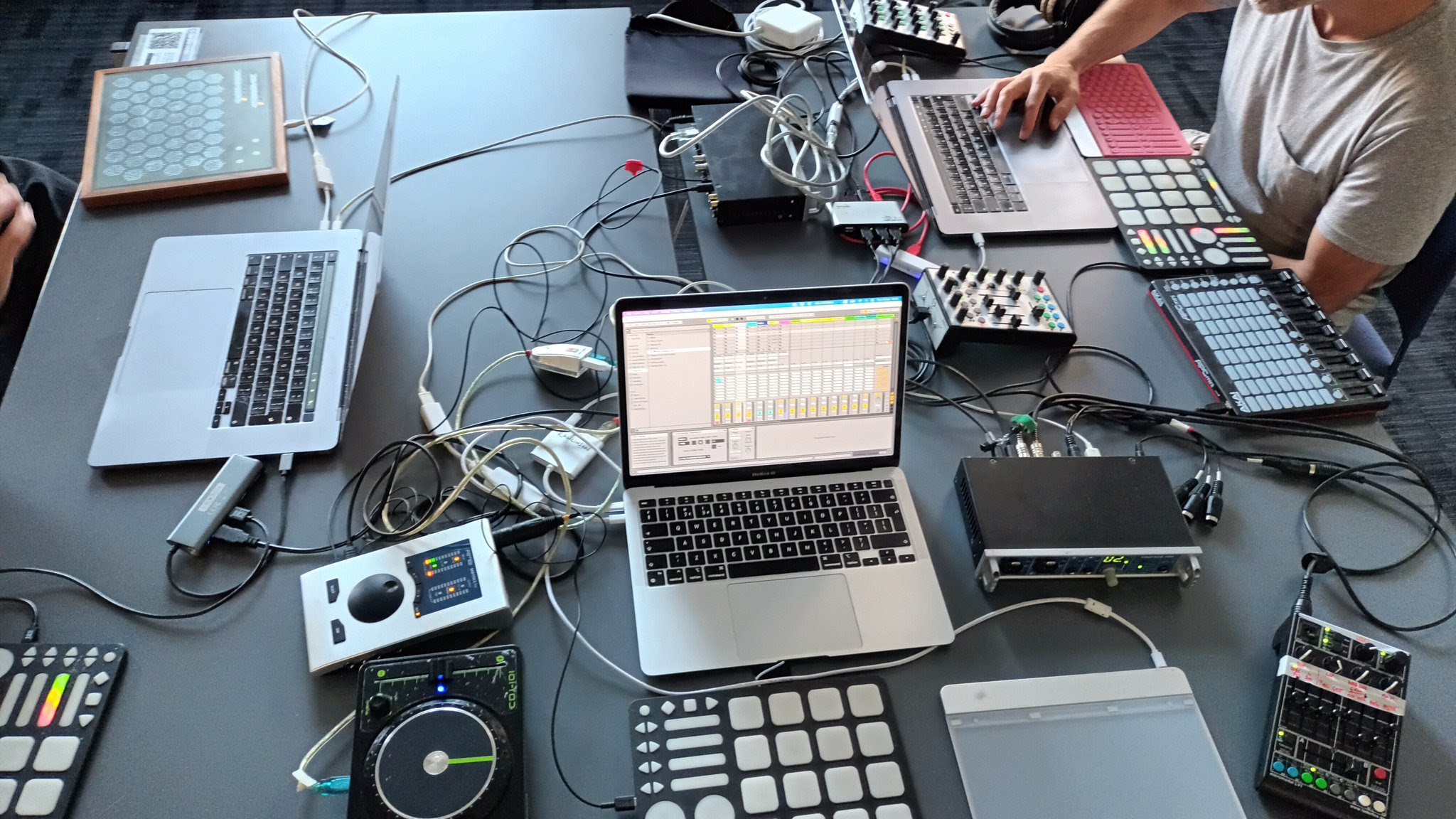

Raw Green Rust is the improvising laptop trio of Jules Rawlinson, Owen Green and Dave Murray-Rust. They define their work as abstract glitch-dub.

I sent them 14 questions via email. They replied with the text below, written during a train ride to their next gig.

“we almost rely on failures”

What’s the role of coincidence and failure in your work?

Failure appears in all sorts of ways: we almost rely on failures to know who’s doing what from moment to moment. The failures of algorithms are a big part of how we make some of our devices. And, of course, there’s the Cascone-y flavour through all the clicks and pops.

Now we’ve started chewing over coincidence: obviously it plays a role in all improvising, and part of the fun is whether any / all of us are alert or agile enough to jump on moments of coincidence and do something with them. But then there’s quite a lot of blind luck as well. As well as a bit of non-coincidence, finding negative spaces to inhabit.

Is what you do music or rather, as Goodiepal said, “about music”?

Owen Green: I’m not sure they’re different things. Music is (partly) about music, which is music et cetera. [I don’t really like my bit here…]

Is your music “a product of our time”? Does it say anything about the way we deal with (the overload of) information and the way we deal with technology?

Jules Rawlinson: The information overload is not what I’m thinking about when we do our thing. It’s a product of our current and past musical technologies and histories, being repurposed.

Owen Green: That, for me, *is* about moments in history because I have this whole thing about technologies being social things and therefore situated through the relationships that form around them. That said, I don’t think I’d claim that we represent the current moment in any special way – all shared activity, i.e all music – does that. When I make devices, part of what I like is finding the points where algorithms break down because their assumptions are violated or whatever, which is sometimes through overloading them, but my fixation there is more with the way techno-scientific rationalism tries to collapse technologies into just being about ends, and ignores the juicy, messy and political aspects of means.

Dave Murray-Rust: For me it’s less about information and more about de-centring agency. The technologies around me shape the way I act, and that feels like it’s more conspicuous with digital, ubiquitous technologies than may have been the case in the past. There’s a lot of in-the-moment agency that I share with the devices, and it’s that that connects to questions of overload and dealing with technology.

Your work is funny, but is it also cynical? Or should I say “critical”?

Owen Green: I definitely prefer critical cynicism, for me, implies being resigned to all the bad, shitty things and using that as cover not to try and change stuff. Being critical though, I think is more constructive. I’m quite attached to the idea that through playing and through designing we can contribute to new ideas about what musicking can be like, and what musical technologies can be like or for.

Jules Rawlinson: Yes.

Dave Murray-Rust: I don’t think our work is critical at all. This set of doings is purely about creating space for things I find joyful – spontaneity, interactions.

Owen Green: Sounds pretty critical to me, boyo.

Jules Rawlinson: Yes. It’s discursive. How we play and interact, the sounds we make and don’t make (and the implied quotation marks around some acts).

Dave Murray-Rust: Ok. So it feeds into critical practice, but that’s not how I approach it. I think I’m trying to protect the moment of playing from being anything other than what it is. I think a lot of the way I set myself up is more driven by selfishness than critique – maybe a rigour about what I want out of improvisation.

Jules Rawlinson: But it always is. Look at how we build in the chance for things to go wrong at every possible moment, rather than using our tools to insulate ourselves against the possibility of failure (we’re back to that…)

Do you see what you do as “radical computer music”, or is that a term that is dated, that doesn’t mean anything anymore in times when a computer is a tool that anyone uses in making music?

Owen Green: I think it would be presumptuous to say whether we’re especially radical. Perhaps we have our moments. It’s not like we’re the first people to play this way, by any means (e.g. the Lappetites). But thinking about it I think is possibly more rather than less urgent the more people are using computers for music making.

Dave Murray-Rust: I think as a bunch of white men in a university it’s hard to feel especially radical.

Owen Green: Quite.

Dave Murray-Rust: The term computer music doesn’t sit right for me. Maybe because it focuses on the computery-ness and we’re more concerned with the way they’re mediating between us.

Owen Green: I guess, yes, we don’t want to be doing the sort of computer musicking that Bob Ostertag thinks sucks.

Jules Rawlinson: In a way, what we do – using controllers and so forth – isn’t radical at all. Compared to Marcin Pietruszewski, who manages to use none, even when performing.

On your Bandcamp page, you call what you do “dub”. What’s the influence of dub in your music? The way you see the recording process and the recording gear as “making music”, rather than “playing an instrument”?

It’s massive, both in influences growing up, but how we approach our sounds and tools. There’s this thing about there being improvisation and curiosity shot through every aspect of the process. Stuff gets stretched, highlighted, filtered, compressed: not just time or particular sounds, but the way that sometimes the processes are laid bare and other times whole, impossible things seem to emerge from the tangle of sounds and boxes. Somebody (don’t remember who) made an argument that almost all interesting electrified music from the 60s onwards was a tradition of “recombinant dub”, which is a nice way to put it. Dub is, in part, a way of sculpting.

Is what you do influenced by the music of Fenn O’Berg and Carl Stone?

Fenn O’Berg is a big influence for Jules Rawlinson. Owen Green less directly (big Jim O’ Rourke fanboy, esp. Gastr del Sol). Carl Stone less directly, but that whole strand of live electronic work coming through the 60s and 70s is massively important.

Except for ‘Inability To End’, every Raw Green Rust release is a live recording. Is this what you do: live improvised electronics and laptop music?

Yes.

Do you prepare for your live performances?

Not noticeably. Although we make occasional technical interventions, they stay with us for a while.

Is “preparing”: uploading samples and sounds that could be used or re-worked during the live performance?

Never as a scripted thing. We all tinker with our instruments all the time, sometimes during practice or performance, sometimes between sessions. But that’s more of a set of independent threads.

Do you make certain deals before you get on stage?

Very, very rarely. And when we have, inevitably between 2-3 of us forget during performance anyway.

Does each of you have a specific role within the playing process or are you “a democracy”?

That varies. When we started, we had more carved out roles, although these weren’t assigned explicitly. Owen Green was “vocals”, Jules Rawlinson was the rhythm section, Dave Murray-Rust was the pitches. That sort of became much more fluid, especially as we got more into borrowing and transforming each other as part of our thing. So now roles tend to get passed around. When we started our different influences probably stood out more than they do now that we’re so imprinted on each other.

How did you get to know each other?

We were all haunting the University of Edinburgh back in 2008. Jules Rawlinson and Dave Murray-Rust were doing PhDs there (in digital composition and music informatics respectively). Owen Green had insinuated his way into the music department, and met both this way. We met at various gigs, seminars and parties. Jules Rawlinson and Dave Murray-Rust started playing, Owen Green and Dave Murray-Rust started playing. The rest was gruesomely inevitable. Our first proper gig as a band was supporting Pole in November 2008.

What do you have in common? What are the differences between you?

Lol.

We have lots in common, especially now we’ve been hanging out for 14 years. We’re all still researchers, and our projects and teaching often intertwine. Dave Murray-Rust has left Edinburgh for Delft now, and Owen Green still lives there but works elsewhere. Meanwhile, we all bring different attitudes (as you can probably tell from the whole criticality thing). For instance, we differ in the specific place this particular band has in the larger mess of projects we’re involved with. For Owen Green, RGR is where quite a bit of research happens, quite directly. For Dave Murray-Rust, it’s a site for thinking about how people relate to technology, as well as an exploration of different forms of improvisation. For Jules Rawlinson, Raw Green Rust is just one of a number of places where he experiments with performance practice.

We do have quite distinct tastes, personalities, and therefore habits. That can sometimes help work out who’s doing what, e.g. if there’s a big lush texture, it’s probably Dave. If there’s a blizzard of clicks, most likely Jules Rawlinson. Scooby doo samples? That’ll be Owen Green.

Owen Green has the most head hair.

Joeri Bruyninckx

Headline photo: Raw Green Rust at Heilbronn | Photo by Vaishak Belle

Raw Green Rust Bandcamp

Jules Rawlinson Official Website

Owen Green Official Website

Dave Murray-Rust Official Website