Bruno Spoerri | Interview | “Pioneer of electro-acoustic music”

Swiss electronic music pioneer Bruno Spoerri has more than a five decades long career and is considered a key figure in the field of Switzerland’s jazz and electronic music. Finders Keepers Records recently released, ‘Der Würger vom Tower,’ a cult jazz soundtrack to supernatural Soho strangler epic that Spoerri held in his vault since 1965.

Having finally been liberated from Spoerri’s master tape vault, this music takes us right back to his first-ever feature-length soundtrack commission (following advertisement compositions for brands like Kodak and the Swiss Co-Op). For an established jazz composer like Spoerri (who would quickly gravitate towards the rise of electronic music to become one of its biggest champions and pioneers) it is easy to identify within this score the early murmurs of minimal electronic sound design and jarring keyboard motifs.

“In 1965 I was just a beginner in film music, so I was very excited when writer Erwin C. Dietrich hired me,” explains Bruno today. “I could see the film only once, received a script with descriptions and timings, and I had just one week to prepare the recordings. I wrote some short compositions, but for the rest we had to improvise. I asked some musician friends to join the session, and for the choral parts I enlisted two teachers (both amateur musicians) as the singers, who we doubled-up to make a choir.” On these rare recordings Heinz Pfenninger’s thick plodding bass notes, complete with double tracking and reverb, embody the classic Bert Kaempfert and Tony Fisher wet bass sound, successfully pinning down the sodden plot against the damp underground canals of Sixties London in conjunction with legendary Swiss jazz drummer Rolf Bänninger as the rhythm section unwittingly channel McCallum and Axelrod in the dark shadows. “The studio producer Walter Wettler had a spring reverb and a simple echo machine which gave me this strange (but cheap) sound” explains Bruno, “It instantly made everything very mysterious, especially with the timpani and the bass.”

Are you excited about the upcoming Finders Keepers Records release of ‘Der Würgervom Tower’?

Bruno Spoerri: Well, I was very astonished, when Andy Votel sent me an email in October 2020, that he had found an old movie with my music. Fortunately I had kept the old tapes. And then I remembered the circumstances of this music.

In 1965 I had just started to compose film music: it started with a documentary about prefabricated buildings, then came some TV-spots. I knew some of the important composers in this field: Walter Baumgartner and Hans Moeckel, both very experienced composers, arrangers and band leaders, and I guess now, that they recommended me, because they wanted to give me a chance and also, because they knew, that not much money was in this job. They also contributed the title music and some further parts, probably with existing stock music.

“I could see the film only once”

How did you approach and offer to make a soundtrack for this fantastic Swiss/German thriller and what were the circumstances around it? When working on this soundtrack you were only at the beginning of your career in the film industry, did you find it difficult? Did you do a lot of improvisation?

I could see the film only once and got a script with timings, and I had just about one week to prepare the recording session. I just could write some tunes and find some musicians who were available: a versatile pianist and organist, a guitarist, a bass player and a drummer, and two quite good singers. I played the saxophone and helped out on the organ for some tracks. There were some timpani in the studio that we could use. And I knew that the sound engineer, Walter Wettler, was a magician in overdubbing and sound effects, and he had a reverb unit that sounded very strange, when it was overdriven. The only problem with his studio (in the concert hall of a nearby restaurant) was that he had no possibility to project a movie, so I had to rely solely on my notes and timings.

When I didn’t know what to do, I told the musicians to play blues changes and I improvised with the eye on a timepiece, so that I could play some accents at the right time. The producer was sitting in the control room, and he tried to speed up the recording as much as he could. So we rehearsed a tune, and after the first trial he came out and told us that it had already been recorded and that we should go on to the next tune. At this time Wettler had only 2-track recording machines. But he was a master in overdubbing, so we could do the triple choirs with the two singers in one take.

“It has a plot so strange and absurd, that it could get to a cult status”

How come that it took more than 50 years to unleash this fantastic piece of music?

I really don’t know how Andy found this movie. I think, fortunately, it is forgotten. But I understand now, that it has a plot so strange and absurd, that it could get to a cult status. I think, it was a financial flop – producer Erwin Dietrich changed to sex films after this movie.

I saw the film once in a cinema in Zurich. Three people attended: my wife and me and the cameraman. Then it disappeared. I found a DVD copy (probably illegal) in an obscure American shop – my name was changed to Bruno Sberri. Atlas Films has now made a legal reissue.

Your career is absolutely amazing. Would you like to take it at the beginning? What led you to become a musician? Would you like to talk a bit about your background? Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

My mother came from a family of musicians. Her jewish parents and also her grandparents – the families Schein and Rewinzon – fled from the pogroms in 1906 from Dnjepropetrowsk (Ukraine) to Switzerland. Her father was a violinist and soon started to play in hotel orchestras in Zurich, then he also began to play in silent film cinemas. All three daughters played an instrument: Gilia the piano, Regina the cello and the youngest, Lore, my mother, the violin. They formed a Salon Orchestra with their father and played in cinemas, cafes and in the new radio station of Zurich. There Lore met a young engineer, my father, who was then the technical director. He came from a traditional Swiss family, his father led a grocery. They married in 1929. In the crisis of the Thirties he was without a job; she formed a “Salonmusik” Trio and played in cafes, hotels and also in a chamber orchestra and financed the family. Finally in 1935, when I was born, he found a good job in a company in Basel. Her career was interrupted in 1939 by the war, after she had won a first prize in a competition. He had to serve in the Swiss army. She was very often on tour with her Trio, and this led to big tensions, until a few years later she left him. I had to stay with my father, and he tried in vain to make a second Einstein out of me. I fear I deceived him a lot.

How did you first get involved with jazz music?

I had begun to play the piano very early with the pianist of my mother’s Trio, but then I got into the hands of a piano teacher, who made me hate the piano and also classical music. When I was 13 years old, some of my friends formed a jazz band. They encouraged me to learn the guitar, but after a year I realized that this was the wrong instrument – then the guitar teacher sold us an old alto saxophone. During two years, when I was in a boarding school in Davos, I was taught by a dance musician, and when I came back to Basel, I formed my first band, the “New Cool Team.” I heard Lee Konitz (with Stan Kenton) and Gerry Mulligan (with Chet Baker) and tried to follow in their (too big) steps. In 1954 our band won a first prize at the Jazz Festival in Zurich with a Mulligan-like Quartet, and this brought me in contact with the best musicians in Basel.

You studied in Basel and Zurich with Karl Barth, Karl Jaspers psychology, would you like to take us back to your student years?

My own problems led me to the study of Psychology. But in Basel Psychology was a very philosophic, theoretical thing; Jaspers and Barth were fascinating, but far away from actual work with people. I wanted to do practical work and so after one year in the University of Basel I moved to Zurich to the Institute of Applied Psychology. I was promoted there with a diploma and continued at the University of Freiburg im Breisgau in Germany with the goal of a doctorate. But I must confess: I was more often on tour with jazz groups than present in the University. But still I got the German diploma and began to work on a dissertation.

You played with groups like Francis Notz Septet, the Modern Jazz Group Freiburg as early as 1956 and were also a member of the Metronome Quintet from 1956 to 1975. I would really appreciate it if you can share as much as you recall about these three groups?

At this time there were no professional jazz musicians in Switzerland, as you couldn’t earn any money with jazz. Almost all good musicians were “amateurs.” The Francis Notz Septet was a fantastic band: Notz (lithographer) was a great tenor saxophonist in the footsteps of Stan Getz, Umberto Arlati (tiler) followed Miles Davis and George Gruntz (still working as salesman for Peugeot cars) was the top pianist of Switzerland. Then I got into contact with pianist Waldi Heidepriem and bassist Karl Theodor Geier of the Modern Jazz Group Freiburg im Breisgau, and together with Arlatiwe toured in Germany. During my studies in Zurich I met the Metronome people (then all students). I stayed with them for almost 20 years, and we recorded many of my early arrangements and compositions – i.e. an LP ‘Swinging Mahagonny’ with arrangements of Kurt Weill tunes of his famous opera, or ‘At the Zoo’ with a Big Band and even some early electronics et cetera. But then I realized that they were not willing to follow me to new ways of playing, so I left them.

When the Sixties came you worked as psychologist and career counselor, but at night played in the Remo Rau and Hans Kennel Quintet in your free time. How was that? What was the scene back then?

After graduation in Freiburg in 1960, I worked (recently married) as an assistant in a psychology center in Biel. After two years I changed to Zurich, because I wanted to start a psychoanalytic schooling. I worked as a career counselor. But only days after my arrival in Zurich I got a call from Alex Bally, drummer of the band of Remo Rau (piano) and Hans Kennel (trumpet) to join their band at the Café Africana. We played regularly one evening per week and also in jam sessions with Dollar Brand (just arrived from South Africa) and other musicians.

Would you say that Switzerland was open to Jazz music in the late 50s and 60s?

In the early Fifties Jazz, most parents and teachers hated jazz (with one exception, our French teacher Walter Widmer, who gave me my first book about jazz). But some years later, especially with the success of the Zurich Jazz Festival, the climate changed. Now, for some years, jazz was the music of young people, until the climate changed again and the youth turned to Elvis Presley, the Beatles, the Stones…and jazz was again the music of a smaller group of people.

There were some very good jazz musicians in Switzerland, but in order to start a jazz career you had to leave the country, e.g. Daniel Humair to Paris, Stuff Combe, Charly Antolini and Pierre Favre to Germany. Some of the leading musicians, who stayed in the country were successful businessmen – e.g. Flavio and Franco Ambrosetti, Hans Kennel.

How did your work for advertising companies come about? What led you to become a composer and sound engineer?

In 1963 I got involved in music for some “Hörspiele” (radio plays) for Radio Zurich and then I got the commission to do a “Poetry and Music” evening with works of Zurich poets. I loved to do a lot of composing for these events, and we recorded them with members of the Hans Kennel group. The pianist of the Metronome Quintet worked in a big advertising agency, and he was asked to do the music for a short movie for Kodak. He couldn’t do it and gave the commission to me. Then followed a second, a third small film, and one day the boss of the Agency, Victor Cohen, called me and told me that he had opened a film company. TV advertisements started in Switzerland in 1965 and he wanted to do these TV spots in his own shop. He said he needed a “Tongestalter” (Sound designer), responsible for all sound, and he promised me the same salary as I had as a psychologist. Just before that, I was still convinced that I would continue to work as a counselor or therapist and do music as an amateur – but then the chance to do something new prevailed. And my analyst told me: “Just do the damn music you always wanted to do” and threw me out of his therapy. So within a few months I was in that company called Televico (Television Victor Cohen), in a new profession that was far away from everything I had done before. Within weeks I had to learn to record with a Nagra tape recorder, compose jingles of exactly 30 seconds duration, cut tapes with an Arri movie cutting machine et cetera. We were a small and young company, TV advertisements were new and nobody knew how to do that – so I was in good company, and we had the chance to try out new ideas. We were lucky; thanks to a genial idea of our art director, we won a first prize at the Advertisement Festival in Cannes with one of our first spots (Bic), and from then on we were in business.

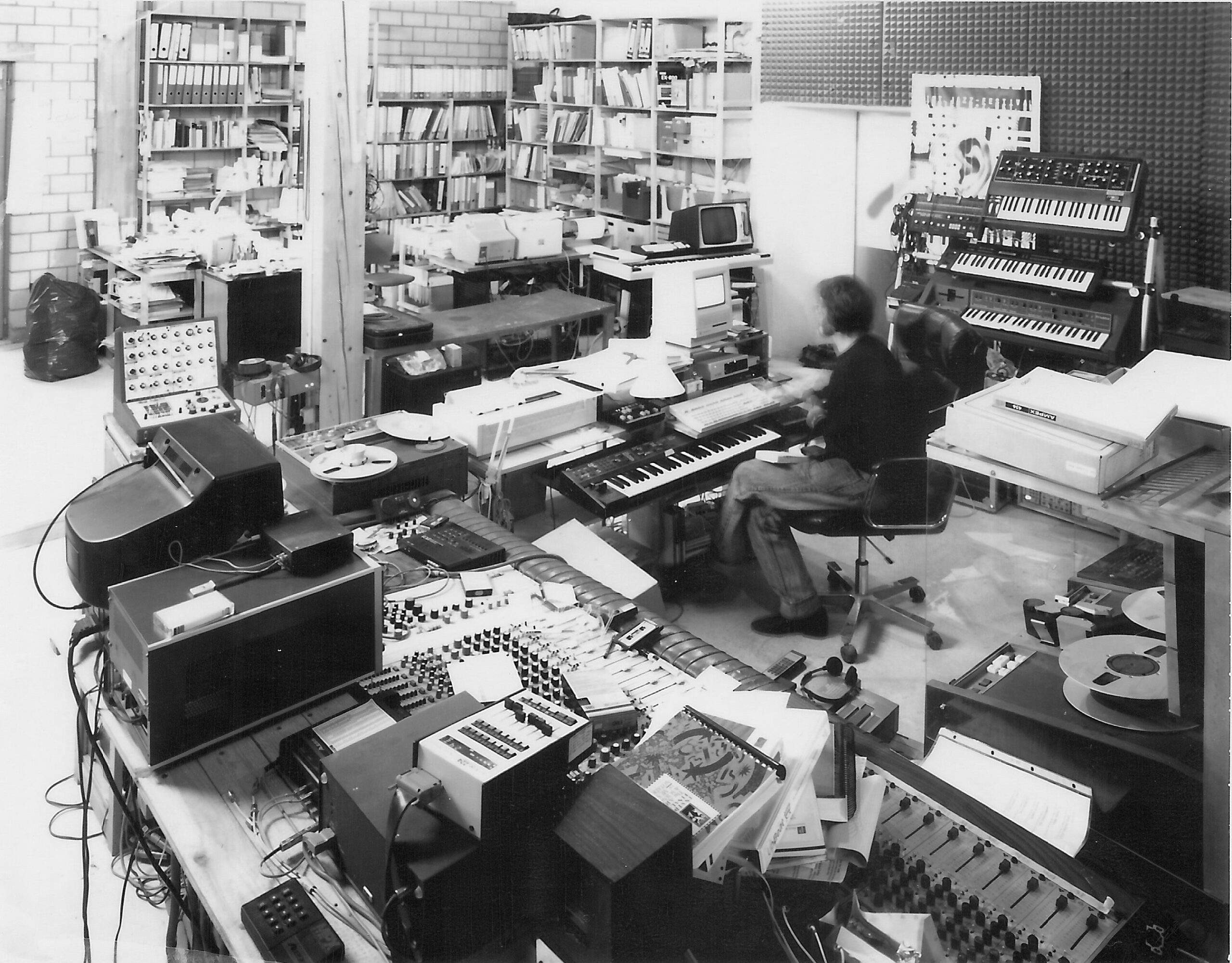

There was one problem: the music budget was always small. I couldn’t hire more than about 3-4 musicians, so I remembered that I had heard an instrument years before that could do wonders. And the sound engineer Wettler was willing to do crazy overdubbing tasks. So I ordered an OndesMartenot in France, one of the first available electronic instruments, learned to play it and got a reputation for doing strange things. Suddenly I was in demand for all tasks, where special sounds were needed. I began to read American music magazines and found an ad for a Moog synthesizer. But this was beyond my reach: 10.000 Dollars, in Switzerland then 50.000 Francs. Finally, in 1970 I saw an ad of an English company, the EMS VCS-3 for about 6000 francs, and immediately ordered one. At the same time I opened a small company with my friend Hans Kennel, because we both were unhappy with the quality of most studios in Zurich. We wanted to produce Swiss music in our own recording studio. We rented a small place with a good engineer – at the same time our Jazz-Rock group “Jazz Rock Experience” had a lot of success, and suddenly my income from TV ads went up and up. I got into a whirlpool of success and acquired in 1971 one of the biggest synthesizers, the EMS Synthi-100. And with this machine came an avalanche of commissions for TV signature tunes, a popular TV quiz, et cetera. In 1974 I could rent a big villa in Zurich with enough room for my own studio, and suddenly I was the proprietor of a 24 track studio. A former producer of CBS founded his own label Image Records, we produced LPs with the new wave of Folk-Rock groups, other labels followed – it was a crazy time. I began to produce Swiss groups and didn’t realize for a long time that I lost money there instead of earning something. With Irmin Schmidt of Can I recorded a LP that got fantastic reviews, but didn’t sell. And towards 1979 I oversaw the crisis of the recording industry, was cheated by some musicians and suddenly found out that all my money went down the drain. At the last minute I closed the studio, found an old house in the countryside with a run down barn and swore an oath that I would never do any production myself anymore. At the same time the advertisement business had changed, I was more and more out of the loop, but instead I got more and more to do with documentary and feature films. Also I got some small teaching jobs that helped to survive, but for some years I was in a precarious situation.

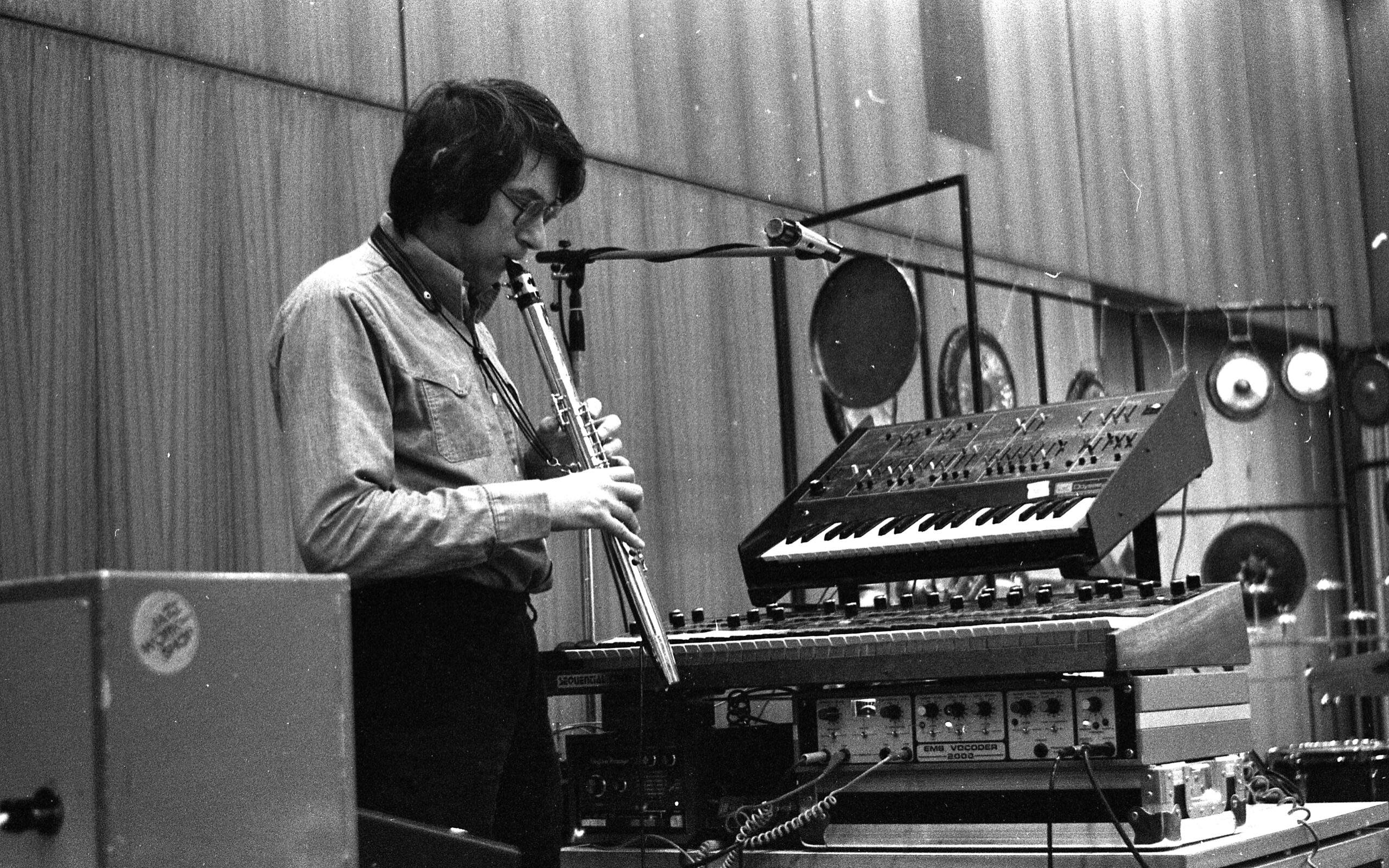

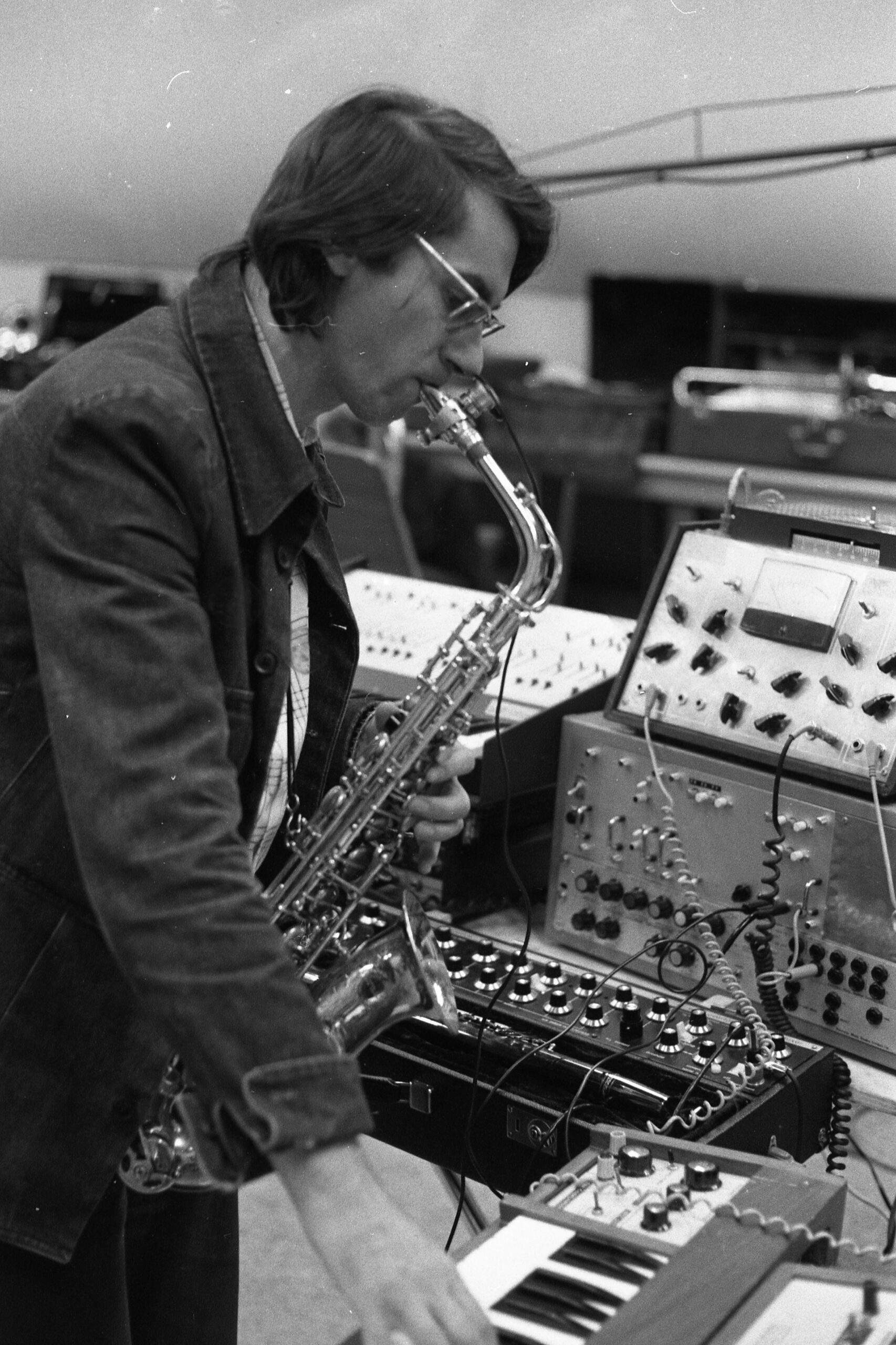

I would really like to hear about the early experiments with the electrified saxophone, effect devices, the OndesMartenot and self-made sound converters, EMS VCS-3 synthesizers et cetera…

I heard the OndesMartenot in a concert in 1955. I loved that sound and I tried to know more about this music. I felt that this instrument fulfilled my dream of being a one-man orchestra. But soon I realized that there was no way for a jazz musician to get into the holy places of electronic music with their expensive equipment. So I had to wait until 1966, when a loan from the film company allowed me to buy the Ondes in France. I did a lot of film music with this instrument. But I was never a good keyboard player – I hoped to find a way to do electronic sounds with the saxophone. Then I found the first saxophones with sound processors (e.g. with Eddie Harris), also the Pitch-to-Voltage Processor for synthesizers, then the all-electronic Lyricon and at last the Synthophone, a MIDI-saxophone built by Martin Hurni in Bern. I am still using the Lyricon II and the Synthophone. My primary goal was always to improvise with electronic instruments, so I never built a synthesizer myself, but I modified most of the analog units I had in order to simplify playing in concerts – with additional switches and resistors I made a sort of preset. Since its beginnings I have used MAX for all my concerts – I built a sort of all-purpose effect machine with this language.

What in particular were you the most interested in?

For me there was always the foremost goal to perform with other musicians – the technique was a way to achieve this, not a goal itself. I think we play for the people who attend, and we should give them the chance to understand what we are doing, so I looked for gesture-controlled ways to play computer music. Musicians, who just hide behind computers, could be replaced by machines – that doesn’t interest me.

A few years ago I interviewed Joel Vandroogenbroeck (RIP) of Brainticket. You were also part of this experimental group. Would you like to share some words about it?

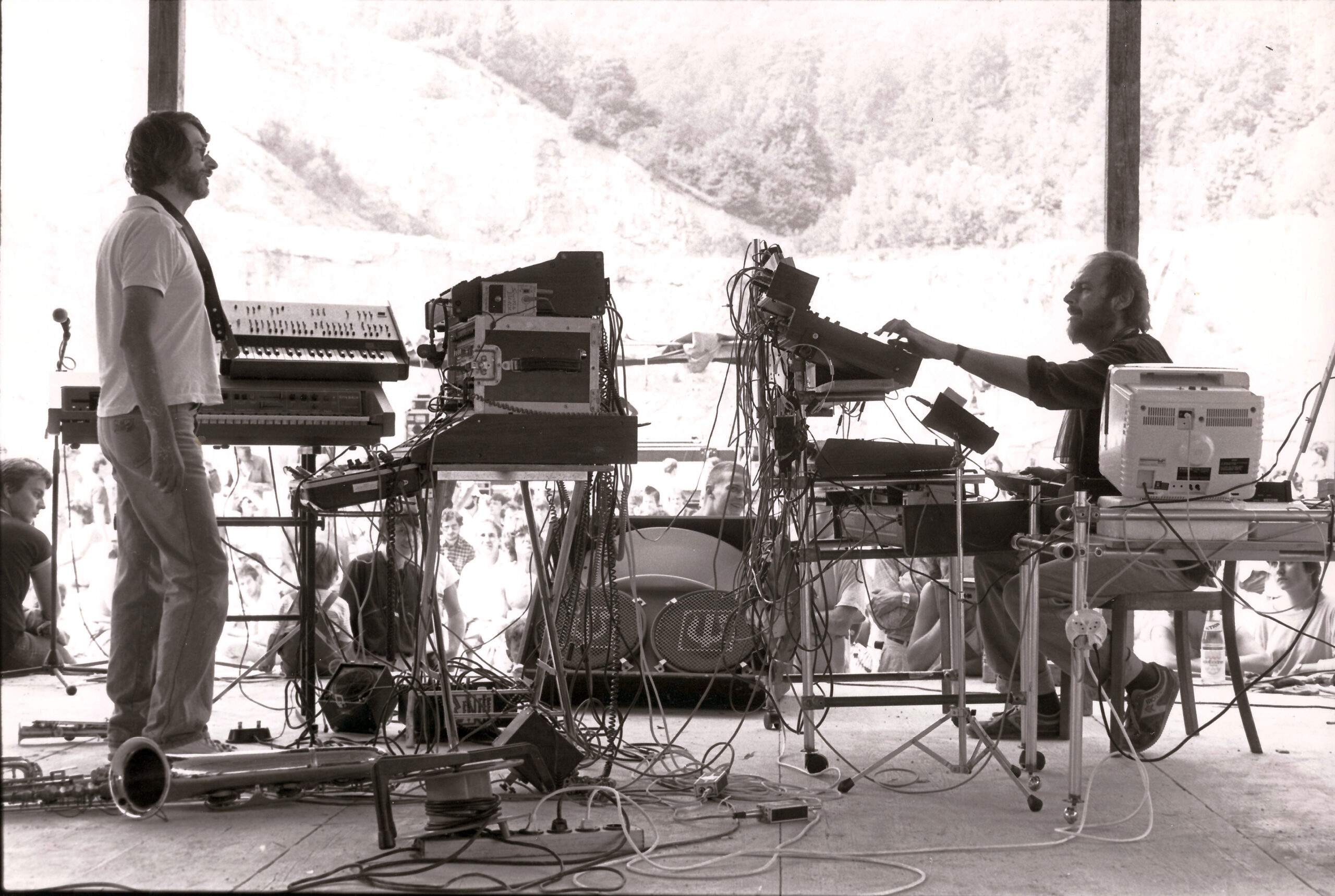

I had known Joel already, when he arrived in Basel – he was the best jazz piano player besides George Gruntz. We did some concerts together, then lost contact. I happened to be in a studio in Winterthur, when he recorded ‘Cottonwood Hill’. And in 1980 we came together again in an improvising duo. I had one of the first drum machines, the Lyricon and an early sampler, he came with some synthesizers, also a drum machine and a bit later an early Apple computer with a sort of arpeggio program, written by his colleague Hans Deyssenroth. We played some crazy concerts together (we did a CD with live recordings, ‘Double Brain’), and then Joel invited me to join Brainticket for a few concerts with Willy Seefeldt and Hans Deyssenroth (CD on Cleopatra Records). Then Joel went to Mexico, and we never played together again.

How did the Container group come about?

When Hans Kennel decided to go his own way, I had to find a successor to the Jazz Rock Experience. I formed the new group with guitarist Thomy Moeckel and his friend, the drummer Mike Murphy, the reliable bass player Hans Foletti, the pianist Nick Bertschinger, and we played mostly our compositions and some of the great pianist and composer Renato Anselmi.

It would be impossible to talk about all of your albums, but would you like to share a few words about the following albums?

‘Hepp Demo Spoerri’

I had invited the singer and pianist Hardy Hepp to do a demo recording of his compositions. Some time later I just began to surround his tunes with improvisations, backgrounds and additional ideas. Then one day I showed him the results, and he liked it, and so we finished this volume together. As in almost all his other collaborations, self-appointed superstar Hepp expected much too much income from this joint venture.

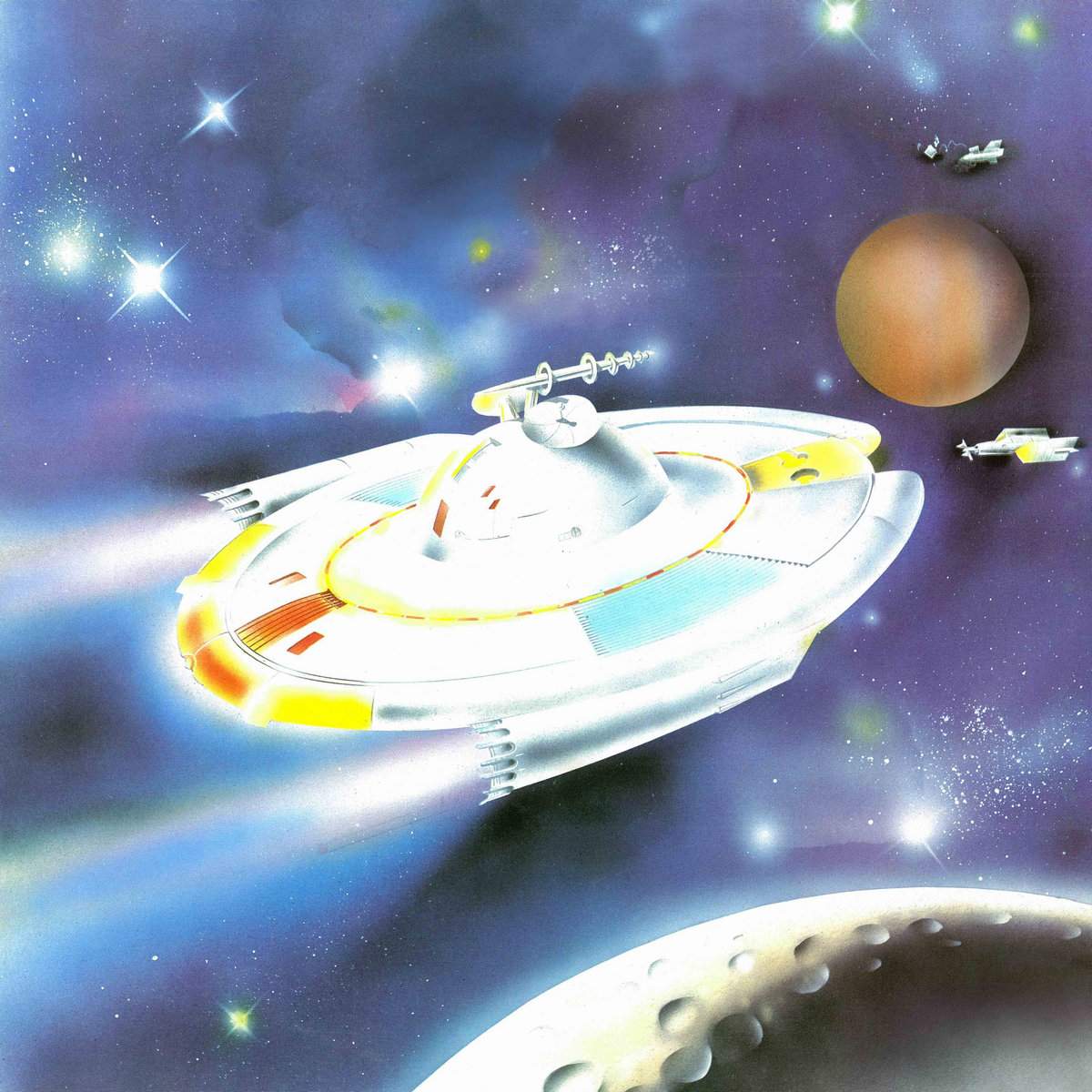

‘The Sound of the Ufos’

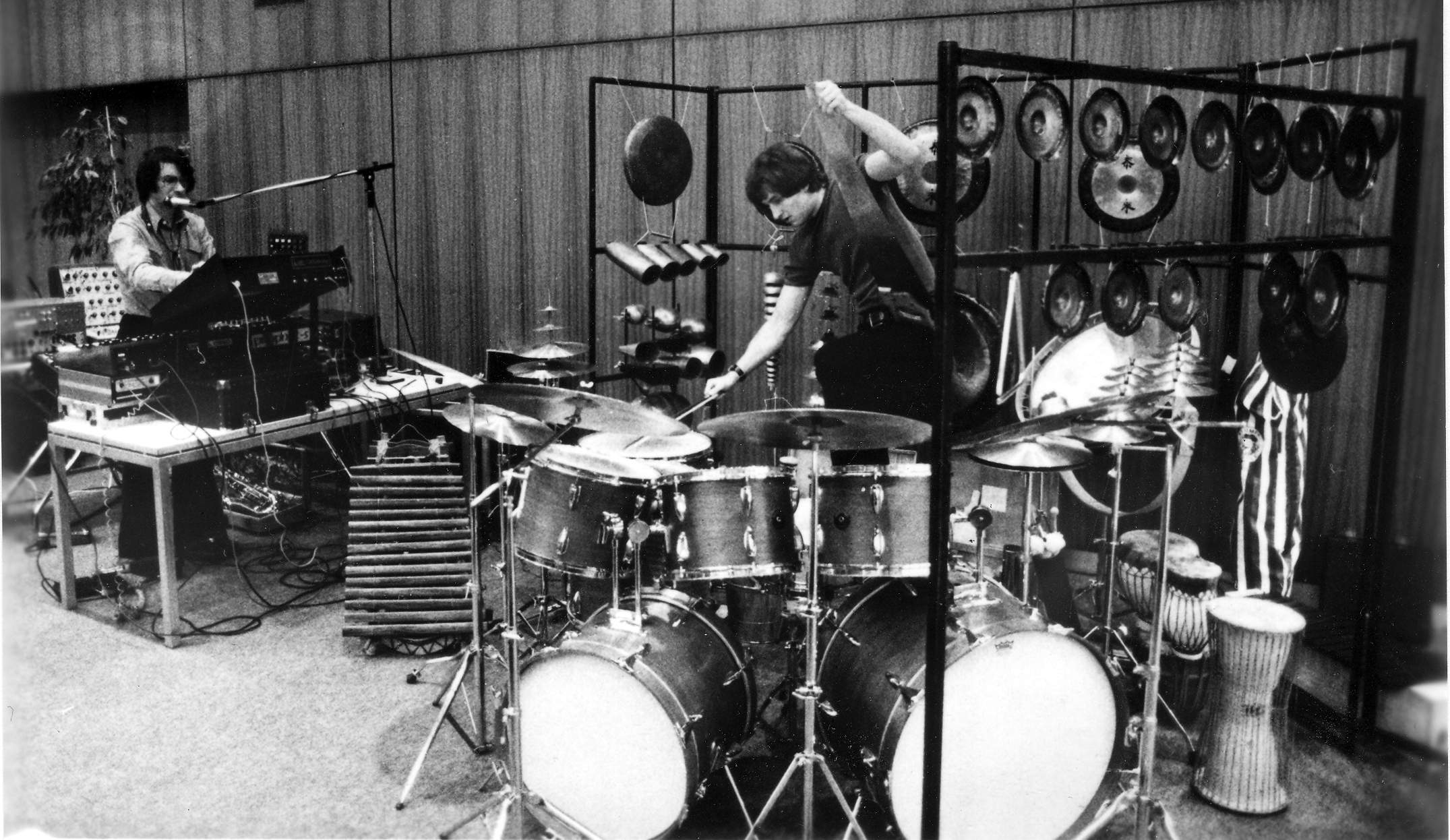

Percussionist Reto Weber was a very innovative partner with a lot of original ideas, so we could do a lot of free improvisation together. So we recorded a concert in Zurich with many unexpected moments. The title ‘The Sound of the Ufos’ was created by the producer, who tried to find a link to the then important Ufo craze.

‘Voice of Taurus’

This LP was the result of some years of development. I had begun to record some tracks years ago without any clear direction, often just as tryouts for new devices. ‘Hallo World’ was the result of experiments with a very primitive ring modulator, who made a very dirty drum sound and inspired me to a tune very much in the fashion of techno guru Giorgio Gomelsky. ‘Hymn of Taurus’ resulted from an experiment with a vocoder. ‘Saxolite’ and ‘Saucers over Montreux’ were live improvisations in concerts that I fortunately had recorded. ‘Cosmotoxology’ goes back to 1970, to an unused and improvised film music track of 1970 with OndesMartenot and a Tape Loop. ‘Quiet High’ I had composed even in 1967 for a wind quintet – I re-recorded it with an overdub of four Lyricon tracks. And ‘Space Cantata’ resulted from a try-out with one of the first digital synthesizers in the world, the RMI keyboard. There was one sound that I really liked, and it inspired me to a melody that reminded me of the film music of Close Encounter of the Third Kind.

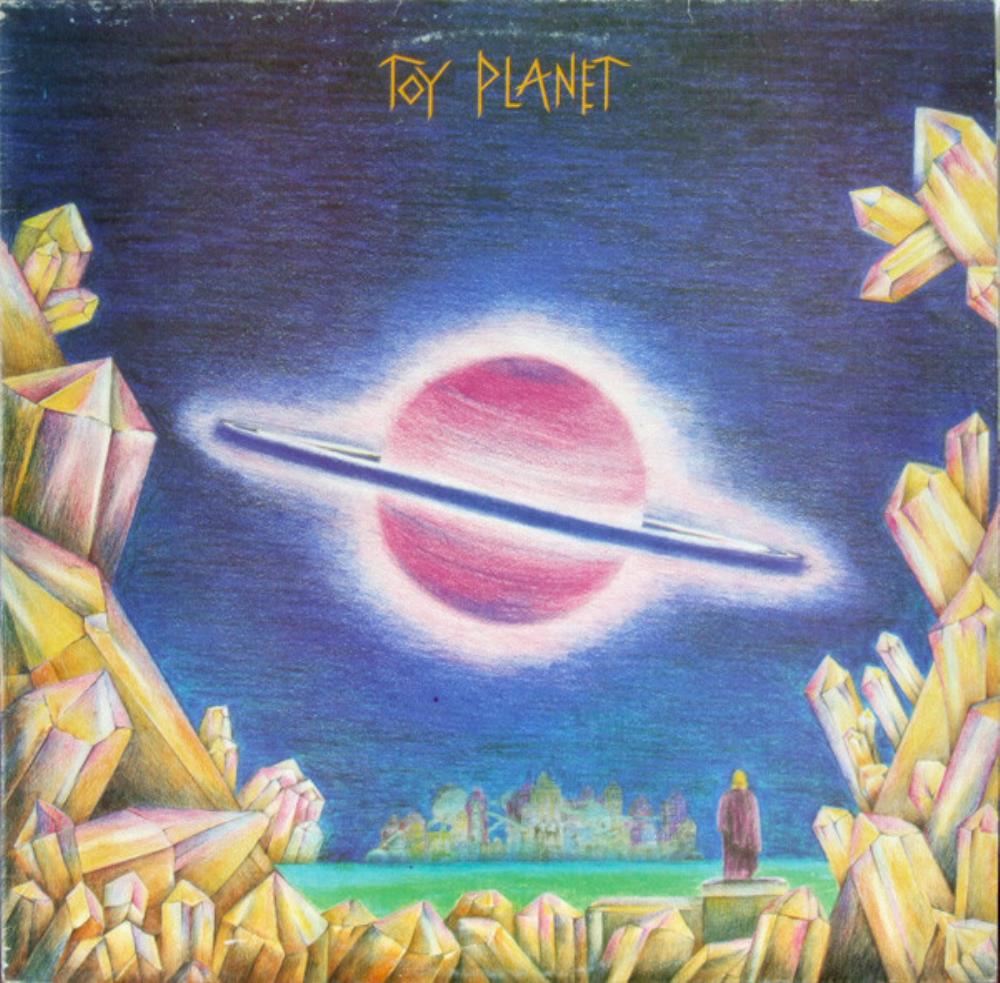

‘Toy Planet’

I had met Irmin Schmidt of Can in a symposium, and he came to my studio to record some of his film music. We had a good time together, and so began the idea of a duo LP. We recorded some bits, then some months later he came back for another session. As there was no sampling at this time, we worked mostly with long tape loops that went through the whole studio. In the meantime I had hired a young sound engineer, Ron Kurz, and with his help the pieces came slowly together. All tracks went through several states of complete re-doing – in the end we spent more than 600 hours of studio time. The LP got fantastic reviews, especially in England, but the sales were very low, and so I landed with a considerable loss of money.

One of the most interesting projects was the so-called Jazz Rock Experience.

This band was originally the “Hans Kennel-Bruno Spoerri Octet,” a band of 1968, that tried to get out of the confines of jazz. I had found a composition from the 16th century from a composer called Azzaiolo, that reminded me of Ornette Coleman, so we transformed it into a tune with free parts. ‘Cheyenne’ was a composition of Hans Kennel in the 11/8, then very unusual. ‘Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child’ is an old blues theme, ‘Let Yourself Go’ is a James Brown tune, ‘Krivo Sadovsko Choro’ came from Hans Kennel’s interest in Eastern Europe folklore – you see, it was a crazy mixture. Then we got the invitation to the Band competition at the Montreux Festival 1969, found a manager and suddenly had a lot of success, especially with the combination of Rock rhythms and free-form parts. I coined the name “Jazz Rock Experience”. Hans and I played both instruments with electronic attachments. With the success came problems: We had to replace some band members, the then still new amplification of instruments was a big challenge, we got into the pressure of the music business, and in the end it ended in conflicts.

What about Peaches and Waves and Isolierband?

These bands originated from my studio work. For film music I worked a lot with guitarist Max Laesser, pianists Renato Anselmi and Peter Jacques, the bass-drums duo of the twins Peter “Peach” and Walter “Wälle” Keiser, and this often led to jamming after the recording. Thomas Heidepriem was a young great bass player. We did some concerts under the name “Isolierbänd” (a word play with the German word for electrical tape), then, after recording sessions with the Swiss-Portuguese singer Gabriela Schaaf we played some more as ‘Peaches and Waves’ (after the Keiser brothers), but everybody had too many commitments, and so we gave up. Unfortunately only a few amateur tapes are left of these bands.

How did you become a musical director of the Zurich Jazz Festival between 1971 and 1973 and from 1975 to 1977?

After winning prizes at the Festival I was called as a Jury member, and so got more and more in contact with Festival director André Berner. Then, as the Festival changed from a Swiss Amateur competition to an international affair, he asked me to help with the choice of bands. As a small Festival we had no chance to win international stars, so we travelled to London and asked the music agencies for upcoming, not yet known bands, that we could afford. And so we could book Chick Corea, Weather Report, Chris McGregor, Brian Auger, Colosseum and others before they were famous. But in 1973 Berner gave up, the costs rose and the risk got too big. The town of Zurich revived the Festival 1975 and I was called as one of the four members of the organization committee. The first two years were a great success with bands playing in the whole city, then everything went wrong. A committee member hired an unknown American Big Band for a lot of money, everything got out of hand and it ended in a disaster.

You also toured as a trio with George Gruntz and Tony Oxley and played with jazz greats such as Clark Terry, Albert Mangelsdorff, Lee Konitz, Lauren Newton, Reto Weber and Ernst Reijseger. What are some of your favourite memories from playing with them?

In 1969 I could play in the international Big Band led by the great Clark Terry at the Montreux Jazz Festival, one of the greatest experiences of my life.

George Gruntz was an old friend, and as I was asked to organize an evening for the Convention of Audio Engineers in 1976, I asked him to form a Synthesizer Quartet together with Emile Ellberger and Stuff Combe, both from Geneva. This led to some more fine concerts together, but then George was much more interested in his Big Band.

Then in 1989 I was asked to organize an evening at the revived Zurich Jazz Festival, and so I could book some of my favourite musicians: Lee Konitz, Albert Mangelsdorff, Lauren Newton for a concert, which I remember as the craziest evening of my life. We did a wild mixture of electronic music, free jazz, songs and recitation. The high point was the rendition of Boris Vians ‘Le Déserteur’ with heartbreaking solos by the singer Corin Curschellas and Lee Konitz. A result was also the formation of the Quartet Movin’ On with Albert Mangelsdorff, Ernst Reijseger (later Christy Doran), Reto Weber and me, that lasted some years and resulted in several CDs. The only problem was, that all the tours with this band were financial disasters for the lesser known members…

You also spend a lot of time writing about electro-acoustic music in Switzerland?

I was always interested in Music history. So I began early to teach occasional courses in Jazz History and also Electronic Music. From 1991 to 2004 I was a regular teacher of Jazz History in Lucerne, and when I had to finish my engagement (at the age of 69), I was asked to write a book on the History of Swiss Jazz. So I had to learn a new profession in old age. This occupied me for three years, and then the Music Department in Zurich asked me to write a similar book about Electronic Music in Switzerland – three more years of very interesting research and many encounters with great people.

What currently occupies your life?

I am now 87 years old, so everything goes slower and I need more time to recover after a concert, but I enjoy doing new things, especially meeting young people with fresh ideas. This year I play 25 concerts, and I try to do something new in each one, because I hate nothing more than routine playing.

It’s absolutely impossible to cover your discography. You appeared on so many albums and have recorded a ton of solo albums. Would it be possible for you to choose a few collaborations that still warm your heart?

The newest are always the best … or so. In any case: The Duo-album with Roger Girod, ‘In Between,’ is the result of two concerts recorded live. As the name says: it is music between acoustic and electronic jazz, a very intuitive rendez-vous with a lot of unexpected results.

Your finest moment in jazz?

There are so many fine moments – I just remember the worst: Three evenings with Dexter Gordon. He was very nice and collegial, but I never felt before and after so inferior in my life besides this giant. I considered selling my tenor.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

Thank you for the chance to give this interview. And I am happy that Finders Keepers gives a second life to the ‘Würger’.

Klemen Breznikar

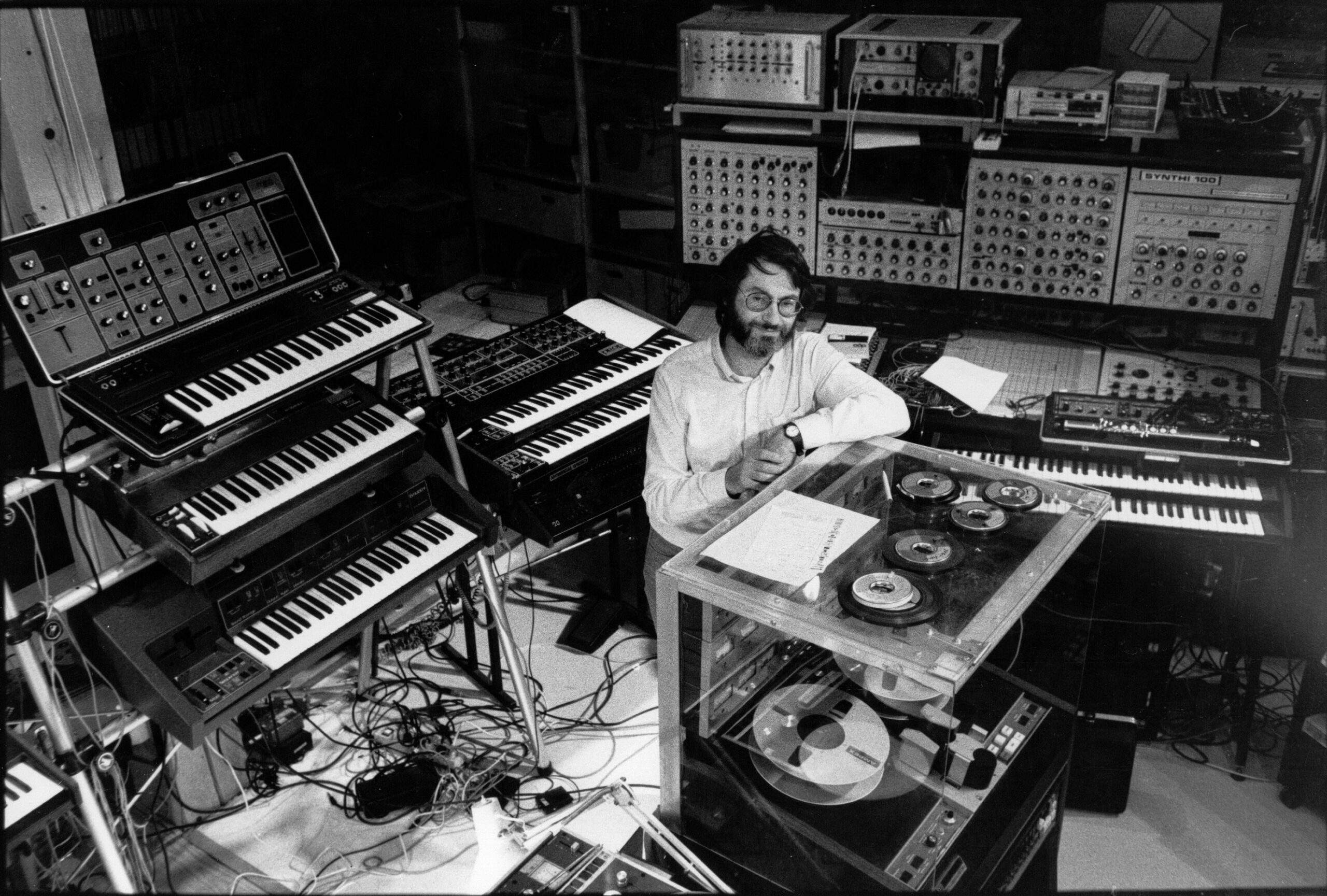

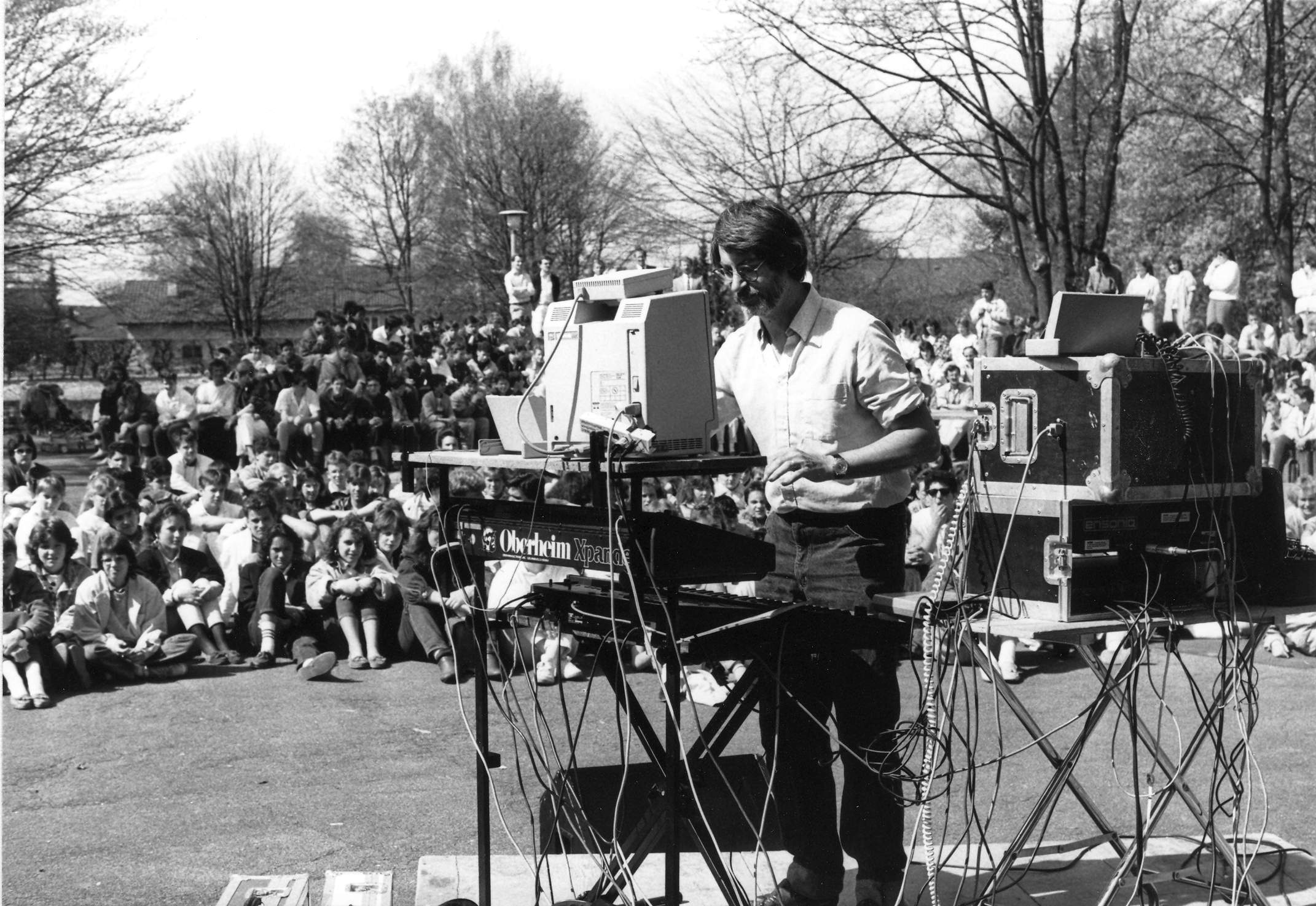

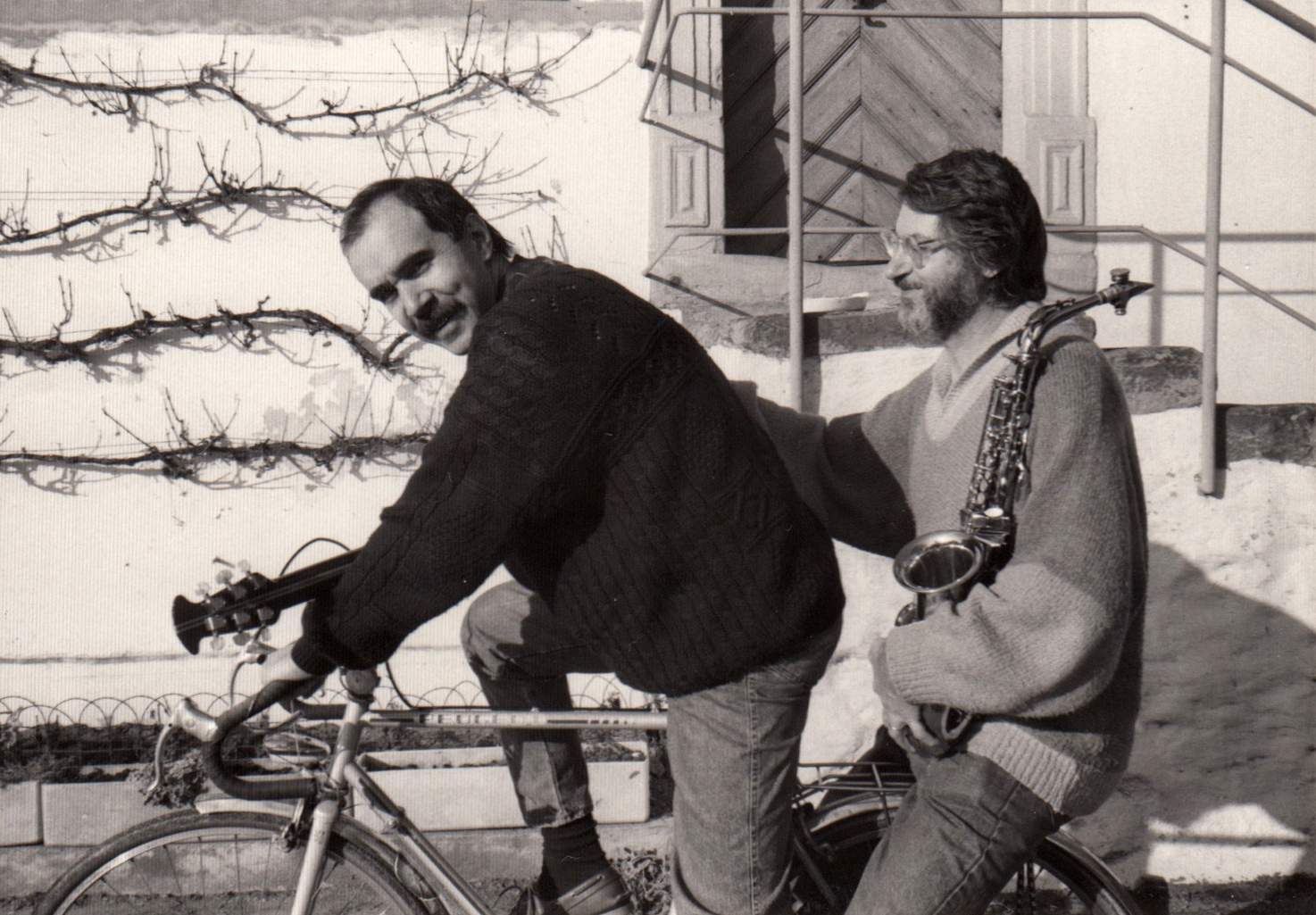

Headline photo: Bruno Spoerri | Studio in Oetwil am See 1985 | Copyright: Niklaus Spoerri

Bruno Spoerri Official Website / Facebook / Instagram

Finders Keepers Records Official Website / Facebook / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube / SoundCloud