Concertgoing – part VI, VII | Listenings by Jason Weiss

From the time I was eighteen, nineteen, I began to get up to date on the jazz avant-garde. That meant a lot of listening, buying records as I could—Braxton, Lacy, Art Ensemble, also earlier innovators—plus borrowing records, finding radio shows on KPFA.

Concertgoing 6: Avant-Garde

Getting to go see that kind of music played live was more difficult, likely because I just didn’t know it was happening or else there really were not many places to hear it in the Bay Area. Somewhere in there, I managed to catch Cecil Taylor in concert at the Keystone, with Jimmy Lyons and Andrew Cyrille in the band, who all showed a remarkable instinct for keeping pace with each other at such an intense level. I also saw a memorably disappointing set of Pharoah Sanders at an odd club on Telegraph corner of Haste, a building that for the past couple decades has been the Berkeley outpost of Amoeba Music, the used and new records wonderland, but back then had a new age juice bar slant, rather forlorn with all that unused space. Pharoah himself played well, his big raw tenor sound reliable as ever, but his presence onstage and his direction of the band, such as it was, became a prime example in my mind of how not to play a set. I mean, if the audience matters. With each piece, the routine was exactly the same: he played the theme, which led into an expansive solo, and when he’d had enough he walked offstage, sometimes to the back of where the audience sat, while the band proceeded to wear out the piece with the same order of lackluster solos every time, until Pharoah came back onstage to close the tune. On the other hand, possibly the first I heard of the new crop of jazz adventurers playing live was an Anthony Braxton concert in ’75 or so. How I learned about it, beats me, a notice in print or mention on the radio; only now, glancing around the internet, do I realize he passed through the Bay Area several times in those years, though somehow this was the sole occasion I was aware of. Seldom a regular reader of the jazz press, I did pick up an occasional issue of Coda Magazine from Toronto and was by then a subscriber to local writer Henry Kuntz’s newsletter Bells, an invaluable guide for me at that moment to records and improvisers I had yet to discover. I also had several of Braxton’s records from the previous half-dozen years: the double-disc solo on Delmark, ‘For Alto’; two records from BYG with his great Paris quartet (my introduction to Leroy Jenkins, Leo Smith, and Steve McCall, as well as to the AACM in general); and his first Arista releases, reflected in the concert we were attending. So, my brother and I and a friend drove the fifty miles down to San Jose State and Braxton presented an exciting concert with several ensembles: a sax quartet and a large group featuring some of the best young improvisers from Chicago and Saint Louis (including Roscoe Mitchell, Julius Hemphill, George Lewis, if memory serves), and also duos or trios with Richard Teitelbaum on synthesizers. For a first dose of all these musicians, it was quite a night.

The idea of a listener’s history: is that not both impossible and pointless, without importance? And yet, we went to so much effort to hear what we did, to listen to that music unfolding. As if it were part of our education, part of the air we breathe. We want to remember whom we have loved, and so music is also like that. Cherished companions, fellow travelers.

In those years I was a college student, I lived at home, poetry and literature were my main engagements, and by 1976 still in my junior year I had a steady girlfriend. All to say, the forces calling my attention were numerous. Added to that, as a writer and a poet I became very interested in theater, I or we went to a lot of plays. In every direction I was tuned in to words and speech, and so the pursuit of music, ever constant, was like a secret channel, a reflection of pure personal curiosity and pleasure.

After listening more and more to the younger improvisers, somehow early in 1977 I found out about an incredible series of solo concerts through the winter and into spring, at a small club in south Berkeley on Adeline Street called Mapenzi. Many a reference to that series I have seen in the forty years since, and glancing at the roster now I’m surprised I didn’t try harder to catch every concert. It was a very significant series, as the small audience knew at the time. I didn’t keep a record of who I saw, but I vaguely recall that I went to hear solo evenings of Oliver Lake, Leroy Jenkins, Don Moye, maybe Joseph Jarman, Leo Smith. Any chance I saw Julius Hemphill there? I don’t think so, but I wish. As if that concert still remains inside me and the right spring could bring it forth, assuming I went. There were others in the series too, and it’s incredible how such a high caliber of musicians came through the Bay Area in an ongoing way like that for months. Did Mapenzi produce it all, cover travel and lodging for these musicians who each played two or three nights? The club seemed too small for that, less than thirty seats I think (forty years later, I’m still going to hear music in places that size). The interior was marvelous, a lot of sculptural and assemblage aspects to the walls, African inspired, to the tables as well, very beautiful, the eye always had interesting corners to alight on. That the music was being heard in such a special setting was not lost on us.

In thinking back on some of the concerts I’ve attended, why do I often recall the venues more clearly than the music played there? One obvious reason is that the physical space, especially sitting inside that space, not to mention the route taken to get there, sets off a complex weave of spatial perceptions and internal mapping all on the way to experiencing the acoustical events, whose physical dimensions remain invisible. Though I have surely gone to far more concerts on my own than with friends, it might seem the social occasions would offer more for the memory to hold onto, but I cannot say that is the case for me. However, as with certain record labels that develop an identity by the roster of artists they cultivate, frequenting a place for its programming or just a single series of concerts locates it in the mind as somewhere familiar, a particular place and time where a kind of family of sounds once lived.

There was one other concert series that was important to me before I left California for good at the end of the ’70s. After a first visit to Europe with that Berkeley girlfriend, in the summer of ’78, I moved to LA to study screenwriting for a while at USC. I only lasted a year, thinking often of Europe, but someone gave me the name of Lee Kaplan or maybe I met him at Rhino Records. Musician and book guy, he produced a series of new music concerts at the Century City Playhouse that year where I got to see some of the finest improvisers in LA: Bobby Bradford and John Carter, Vinny Golia, Horace Tapscott (didn’t I go hear his Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra in South Central after that? or did I just wish so?), Buell Neidlinger and Marty Krystall’s band, Glenn Ferris (whom I was surprised to see again the following year, sitting in with Lacy’s quintet at the Dreher in Paris), probably Nels Cline as well. Again, what an amazing series to have seen, and all those musicians lived in the area. For me to behold such ears in LA—where I did not take naturally to the lures of Hollywood and I was still quite young—was to find reaffirmation of the creative life, whatever that turned out to be.

Concertgoing 7: Paris

To think of concerts seen, attended, heard; and if not of the music that we seldom can recollect, then of its circumstances as well as our own. We remember that we went, though memory makes sure to insert its errors. With some exceptions, the singularity of the event escapes us in the long run. The mind returns, as the body had done, to the venues or halls or intimate spaces that we frequented to hear such sounds. The atmosphere, the tone of those places remains with us, more than the musical organism that came into existence for a while that night or day.

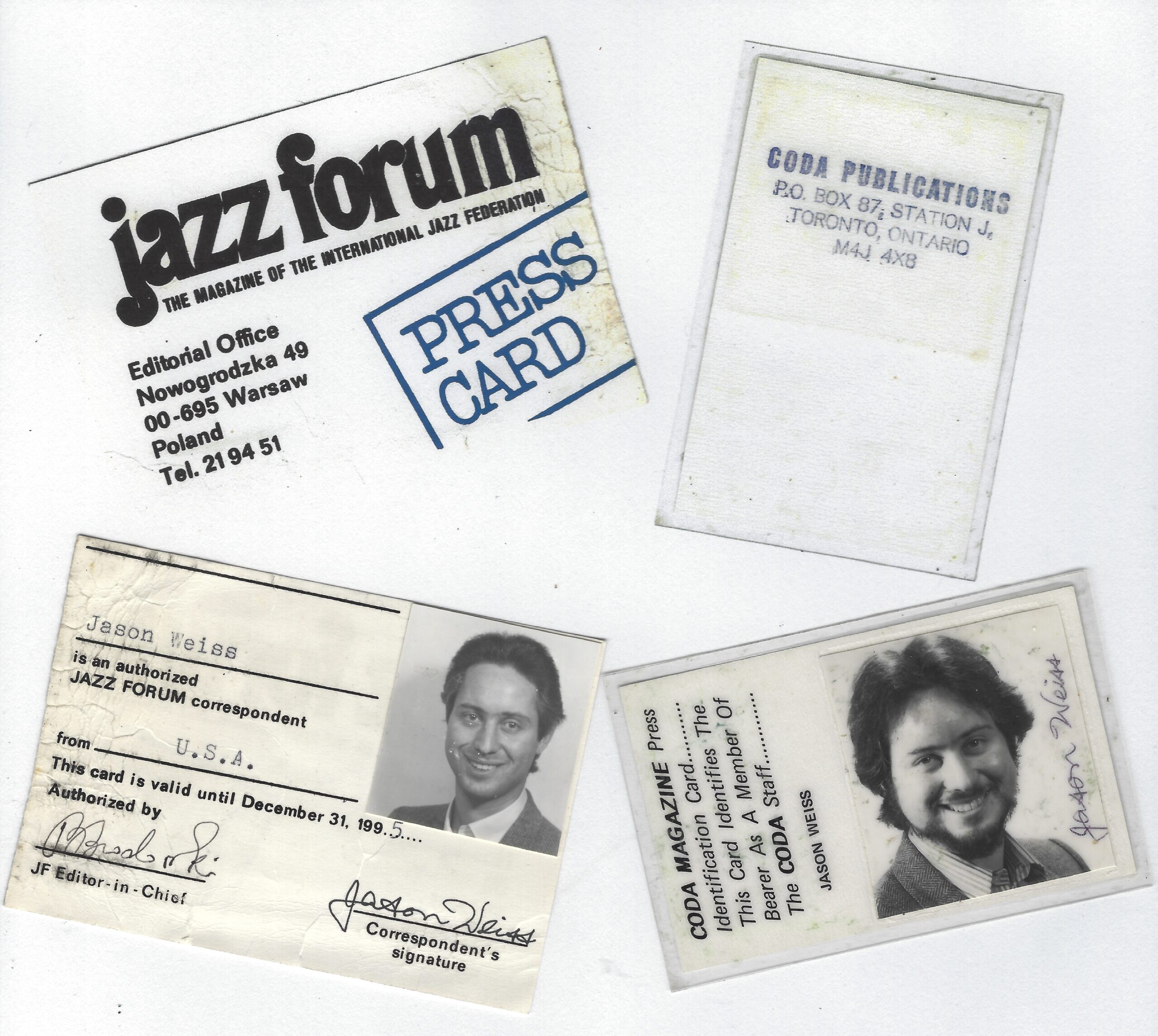

After I moved to Paris, I went as often as I could to hear music, if it was free or affordable, and the more I looked the more I found. In my first months there, spring 1980, I saw the double bass player Maarten Altena do a solo concert at the Dutch Cultural Institute; the trumpeter and composer Bill Dixon, jazz pioneer from the 1960s, playing in a famous old cave on the Rue des Lombards; and Mike Zwerin’s group at the American Center. I wrote about all those performances, among my first writings on music. So, see, listen, hear—for me—became see, listen, hear, write. Sometimes, at least. Enough to earn me a press card from Jazz Forum, the English-language journal of the International Jazz Federation, edited in Warsaw, and also from Coda, the jazz journal in Toronto. These cards got me into a certain number of concerts over the years, even if they did look a little homemade. But I continued to write about music all through the decade I lived in Paris. There was so much to listen to in that city, for me at that time, and it was the first place I’d lived where you could get everywhere by public transport.

That grand old three-story edifice with its garden on the Boulevard Raspail, long the residence of the American Center, was one of the places I frequented in those years. By summer, I was also going to the Dreher, a jazz club off the Place du Châtelet, which closed a year or so later. The club was in the basement, beneath the brasserie-café. I heard Steve Lacy’s quintet there for the first time, and members of his group in another formation, and I think later still Lacy in duo with Mal Waldron. The World Saxophone Quartet played there too. I went to see them twice that week, but one time we got in with the band, Ali and me, since we were helping carry instruments downstairs to the club. Somehow he had engineered for him and me to take Julius Hemphill to a couscous restaurant, Le Casbah, in the crumbly neighborhood where I was living near the métroPernety and from the same establishment to score some smoke for the distinguished saxophonist. From there, we took a taxi to the club.

But, I have to amend what I said before: we also, in a number of instances, don’t remember that we went. I am certain there are many, many concerts we, I, don’t recall having ever attended.

The next year, after I moved to the Rue Monge in the fall of 1981, I discovered the Dunois, a ground-level loft type of space down in the thirteenth arrondissement. In the years I went there, I saw many free improvisers from Europe and the US, always a challenge for listener and musician alike. I don’t really remember most of it, but the list of people I saw would include Derek Bailey, Lacy, the Workshop de Lyon, Evan Parker, JoëlleLéandre, George Lewis, Lol Coxhill, the Rova Sax Quartet, Conny Bauer, Peter Brotzmann, and on. From my six-floor walkup near the Place Monge, I figured out a route strolling down through the fifth and into the thirteenth, following how the streets fed into each other all the way to the Rue Dunois. Most of the time I went alone, and inevitably there was a sense of excitement about the music we were all about to hear.

The club I frequented longest in those years was the New Morning, which opened in ’81 and is still going strong. Up in the tenth arrondissement, on the Rue des Petites Ecuries (Street of Little Stables), it was a cavernous space once you got all the way inside, warmed up a bit by the poster-size blowups across the walls of African postage stamps honoring American jazz musicians. The New Morning featured some of the bigger acts. So, usually in the company of Ali, I got to hear a long fantastic roster of artists: Archie Shepp, Sam Rivers, Max Roach, Lacy’s group, the Vienna Art Orchestra, Art Blakey, Mike Westbrook, Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath, Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra, Cecil Taylor, Dizzy Gillespie, Toto Bissainthe, Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens, not to mention Ali’s own band, Sir Ali’s Girls. And in about ’86, Ali and I hung out with the legendary Prince Lasha between sets, sharing a joint with him as we walked up and down the street. Such lucky encounters—this was Paris! Nor did it escape my mind that we were just around the corner from Cortázar’s last home (where I had interviewed him a few years earlier): I never saw him at the New Morning, but he might well have been there in spirit.

Jason Weiss

Concertgoing – part IV, V | Listenings by Jason Weiss

Concertgoing – part I, II, III | Listenings by Jason Weiss