Didier Malherbe | Interview | Legendary Gong Member

Didier Malherbe lives an extraordinary life. His path crossed many iconic figures.

Malherbe dived into cultures all around the world and played nearly 2000 concerts with bands like Gong and Hadouk. An interview with musician and poet Didier Malherbe.

How would you describe your life so far?

Didier Malherbe: Life is exciting. I’m still optimistic, although I had some health problems recently. A couple of years ago I broke my jaw, which made it difficult to play saxophone. Now it is getting better. I play mostly duduk and flutes, and discovered some new instruments from China (hulusi and bawu flute), Laotian khen, Ukrainian sopilka et cetera. We have recently performed a gig in Paris in a club called Le Triton as Hadouk Duet, Loy Ehrlich and I. It was pleasurable. We will tour again, but not to the previous extent. I played maybe nearly 2000 gigs in my life! Growing a bit old, touring can be tiresome but after performing I feel so good that I want to do it again.

Let’s start from the beginning. What made you become a musician?

I became involved in music when I was about 13. My brother was two years older than me. He was giving parties, where I was the DJ. I played New Orleans and Middle Jazz records. And then I listened to ‘Bird and Dizz’ by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker with Thelonious Monk on piano. All I wanted to do was to play in that style. I rented a trumpet, but didn’t like it, because it was hurting my lips and tasted weird. So instead I rented an alto saxophone and learnt with a teacher. Later I started to play jam sessions in France and then, travelling in England, I heard some tenor saxophonists. When I came back to France, I traded my brilliant alto saxophone against a very old American tenor. It was not as good but I enjoyed it. I was listening to a lot of Coltrane and Rollins and Stan Getz. Some clubs gave me the opportunity to jam in front of audiences. With little pay, of course… There was a club called the Chat qui pêche. On Saturday night you had great players around like Jackie McLean or Don Cherry. On Friday night and Sunday afternoon we, amateur players, had our chance. This is how I started: playing jazz standards.

What led you into the Rock field?

I got a semi-professional engagement in a theater play called Les Idoles. The music was composed by Stephane Vilar. That’s where I started to play tenor sax in a Rock style. We played in Paris for more than a year. There was an awesome group feeling and the piece became quite popular. The actors became famous in France, Bulle Ogier, Pierre Clementi, Jean-Piere Kalfon. The play was about Pop music. And then the year 68 happened. We were doing some gigs with the Living Theater of Julian Beck, an American group living in Europe.

At that time you attended a concert of Soft Machine. What was your impression of the band?

I really enjoyed listening to Soft Machine in a gig called “The Pink Window.” There was Kevin Ayers on bass, Robert Wyatt on drums, Mike Rattledge on keyboard. Robert was singing with a soft high voice, Kevin with a low one, and the Jazz was also there. They were swinging a lot, in an original style. On top they were playing odd time signatures. I was acquainted with this, because I had listened to Indian music. In Jazz, musicians did not play these odd measures, except ‘Take Five’. Otherwise everything was in 4/4, sometimes 3/4. For all those reasons I was very enthusiastic about Soft Machine. Daevid Allen was one of the creators of Soft Machine and an earlier member.

How did you get connected with Daevid Allen?

The day after this Soft Machine concert Hans Neuenfels, a German poet and actor connected with the Living Theater, introduced me to Daevid in front of the Cafe Les Deux Magots. He was just passing by. We followed him into a camping place in Boulogne. There was a big caravan full of Americans. We played there all night and chatted a lot. This groovy night was the beginning of my adventures with Daevid and Gilli Smyth [Daevid Allen’s girlfriend and co-founder of Gong – e.d. note]. He had some visa problems and couldn’t get back to England. So he decided to stay in France. Soon the French started to like him, because he had a humoristic way of speaking French and was a fine musician, singer, poet and composer.

1968 was an important year in general. How did you experience that period?

The Summer of 68 was brilliant. The young ones had revolted with actual results. Not so much in a political sense, but in lifestyle. It was liberation. Some friends and I went to Deya, Mallorca. The first artist who came and lived in Deya was the great writer Robert Graves. I connected with him over Greek mythology. In autumn I spent a few months in a cave which was located in the garden of his house. When I came back to France, we started Gong as a community band in Normandy. That was before the album ‘Magick Brother’.

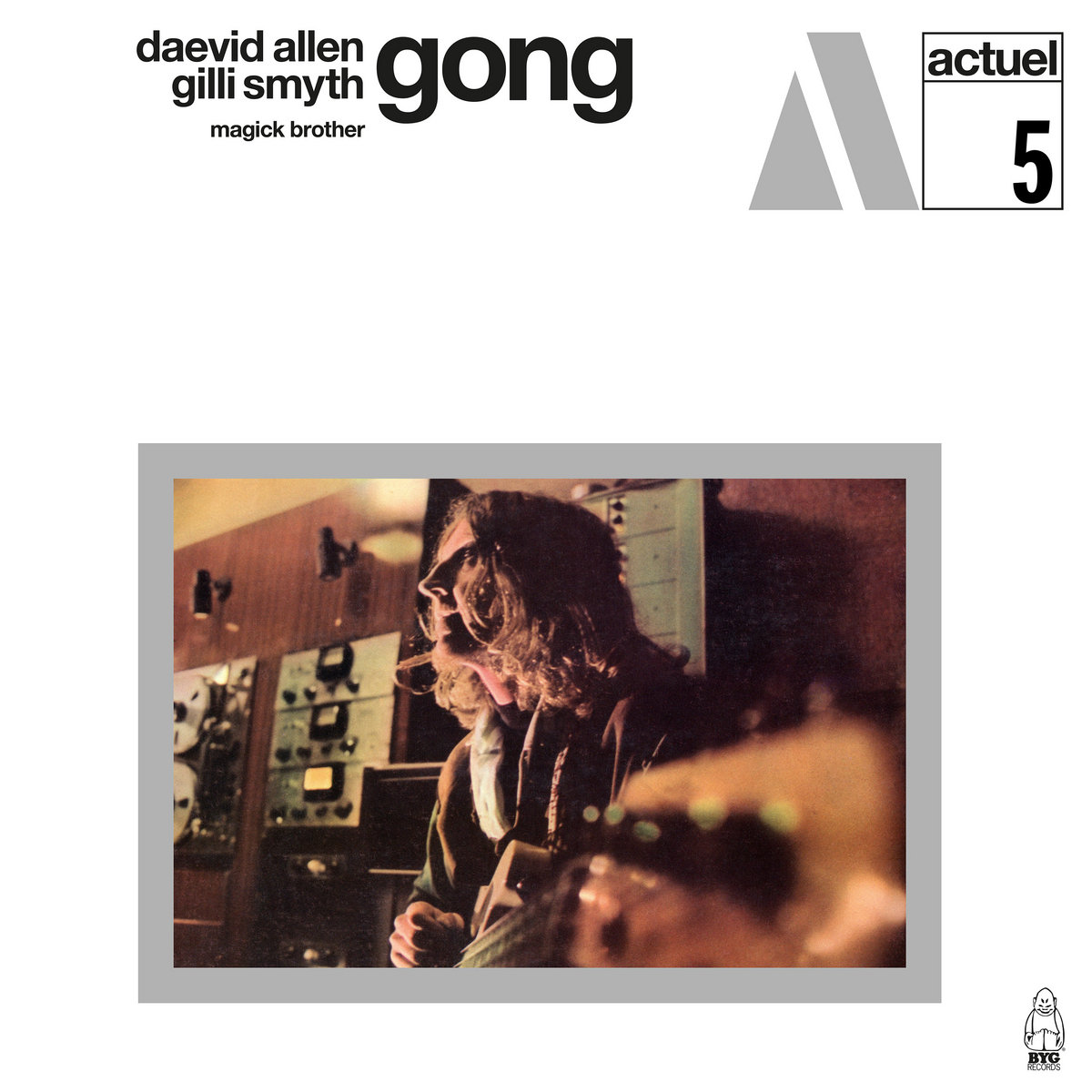

‘Magick Brother’ is considered the first Gong album. How were the early days of the band like?

‘Magick Brother’ is pre-Gong or proto-Gong. It is a Daevid Allen album. I played the wooden flute. I was seeing Daevid often. We decided to start Gong. Daevid was responsible for the Gong mythology and the early compositions. We played our first gig in Amougies, Belgium, on 27 October 1969. It was a festival for Jazz and Rock with two stages. The French authorities rejected the idea of a Rock festival. So it happened in Belgium in a town close to Waterloo. The Jazz stage had acts like the Chicago Art Ensemble. On the Rock stage Frank Zappa was the master of ceremonies. Captain Beefheart, Soft Machine and Nice were part of the line-up. Our slot was early in the morning.

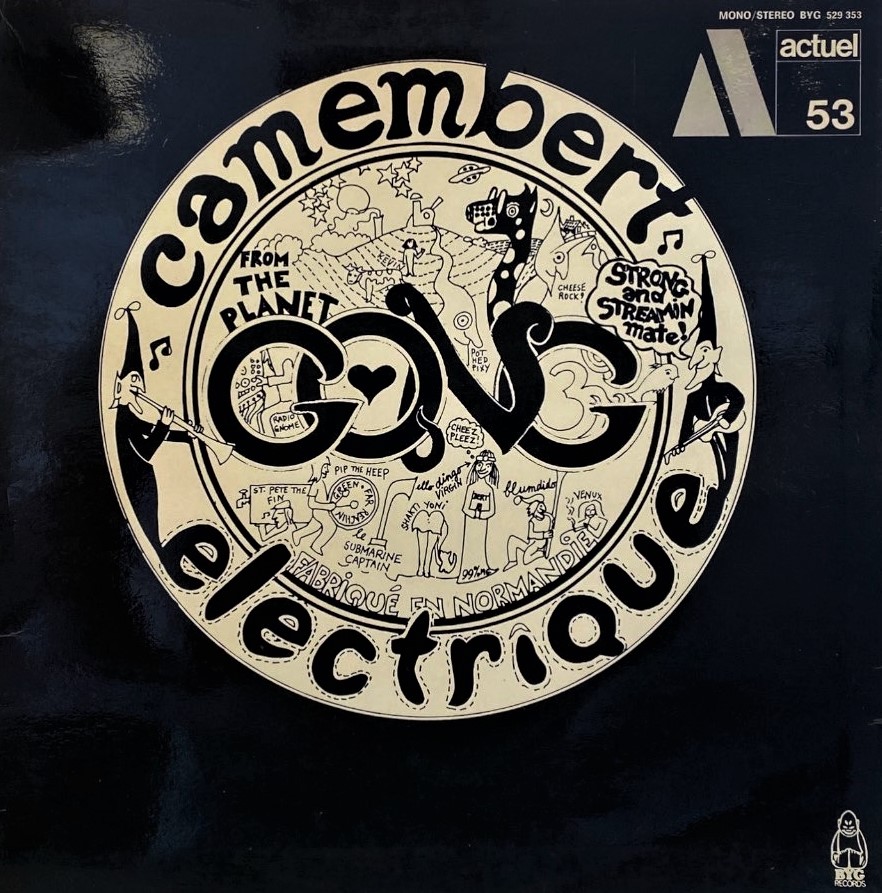

We played a mix of Daevid’s songs from ‘Magick Brother’ and group improvisations that became the material of ‘Camembert Electrique’. There was also a French comedian reciting Victor Hugo’s Waterloo poem. The whole thing was quite surrealistic.

Originally you were located in France. What made you move to England?

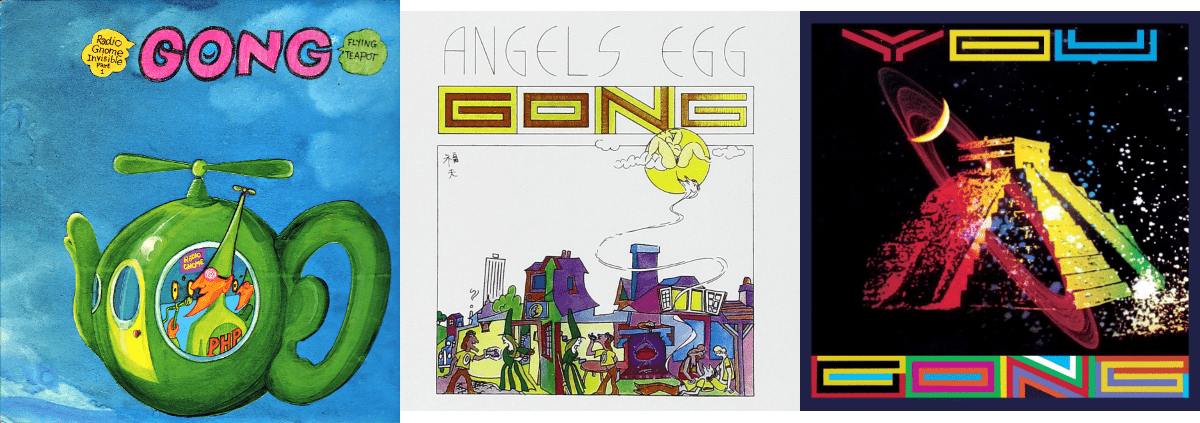

That is right. We lived together in a country house and eventually were invited to play the first Glastonbury Festival. The whole group moved to England. We dropped with our label BYG and signed up with Virgin Records, where we did the ‘Radio Gnome Trilogy’ and some other Gong albums. Virgin Records was completely new at that time. Richard Bronson was selling records to the students, which were cheaper than the usual ones. It became bigger with the success of Mike Olfield’s ‘Tubular Bells’ for the film The Exorcist.

The label was also focusing on imported Krautrock music. We weren’t the only European Band on the label. There were groups like Tangerine Dream and Faust from Germany.

What changed after you moved to England?

After we moved to England, we started to tour like mad. We played big venues, Victorian halls like the Newcastle City Hall, Hammersmith Odeon or Birmingham Town Hall. All these places started to be open to Rock music. We moved into a farm near Oxford, where we stayed a few years as a community. We all had funny names. Mine was Bloomdido Bad de Grass.

“Humor saves the world”

The Gong universe is full of a certain kind of humor. Which role did humor play in the creative process?

Humor saves the world. Daevid was very funny. We were involved in Pataphysics. That was a big thing. We mixed languages. We had a lot of fun and there is a lot of double meaning in the lyrics. It was very pleasant to live together. As a kid I was a bit solitary, so I was lacking a community feeling, which reduces the risk of depression. We all supported each other and pushed into the direction of composing and playing live music. The road managers lived with us too. We all drove numerous miles on the road, mostly in England and France, a bit in other European countries.

It seems like you guys had a good time. Was there anything like work ethics in the community?

Absolutely. The community was creative. We were there to work and compose together. At the beginning it was mostly Daevid’s part. When the great guitarist Steve Hillage joined, and also Tim Blake, the talented synth player, everybody started writing or giving ideas for arrangements. It became more and more Gong. Daevid himself was a good leader and didn’t want to be autocratic. It was a democratic thing.

The Gong universe is heavily connected to psychoactive substances. How do you feel about that?

We enjoyed smoking grass and were tripping sometimes. I think that LSD brought more growth in optical than in acoustic terms. It changes the eyes, the visual perception and the mind flow but on the acoustic level it distorts less, from my experience — although you can feel the importance of the substance when listening to The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd and some others (including Gong…)

In the movie Chappaqua from 1966 the main protagonist tries to get rid of his addiction. You are credited in the soundtrack composed by Ravi Shankar. How did this come to happen?

It is a very interesting film. I met a young American chap, who was living in the hotel Stella in Paris. A lot of Beat-Poets lived there. He was working for Conrad Rooks, the director of the movie. Ravi Shankar was looking for a Cymbalum player [an Hungarian-Russian string instrument, e.n.]. We went to clubs with him, where they played traditional Russian Music. We actually found a Cymbalum player and dragged him into a studio. I met Ravi Shankar there. He was a very nice man. I played some bamboo flute with him, but I was not good enough, I had just started. At the end I played classical flute for the soundtrack. The music is excellent. I still remember the compositions years after. The original plan was to have a record with one side of Ravi Shankar’s compositions. The other side was pieces by Ornette Coleman but they didn’t use them for the film.

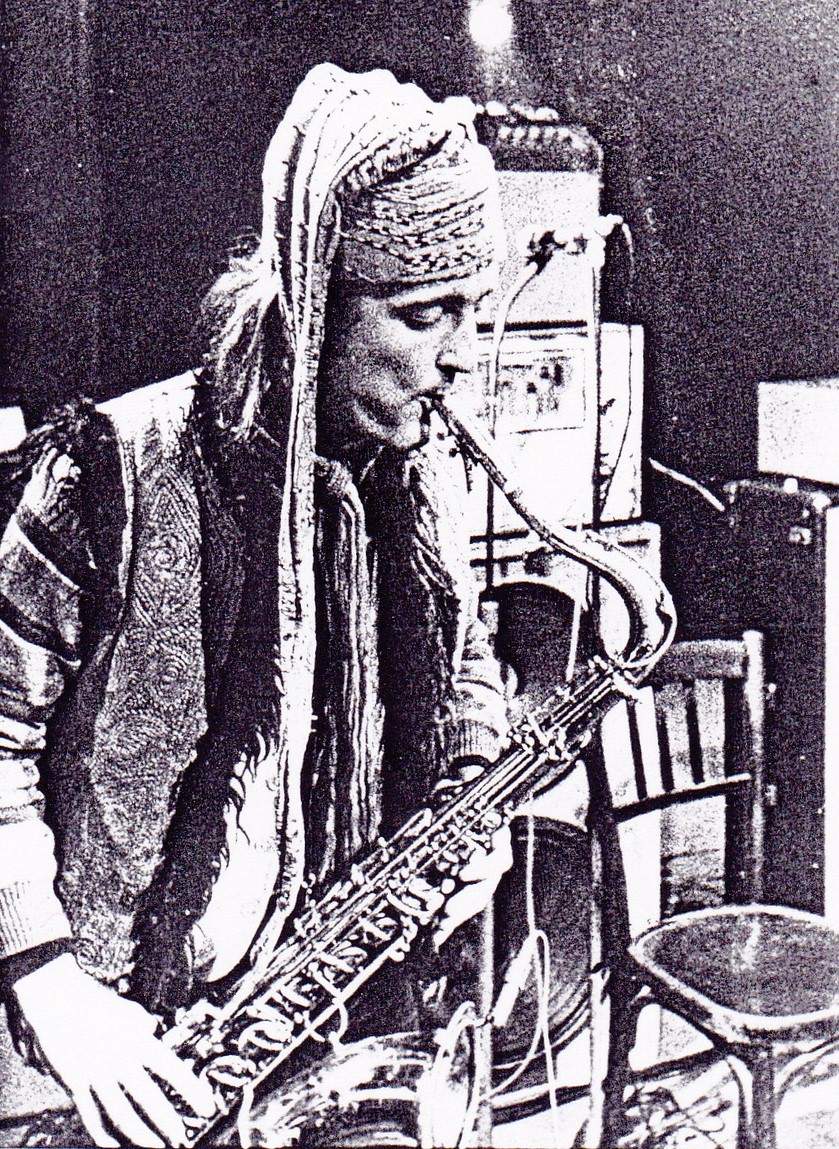

Your sound on the Gong recordings is very unique. What brought you to that?

In Gong, I mostly played the saxophone. Problem: the electric guitars were always louder than me. When we played the Glastonbury Festival I met Elton Dean, the sax player of Soft Machine. He gave me an address in London, where they made harmonizers and amplifiers to modify the sound. I started using Wah-Wah pedals and things like that. Later on I played a midi saxophone, but it had a strange effect: You get involved in the electronic thing and lose your original sound. I recorded some albums with it but after a while, I turned over to play only acoustic instruments. And then I discovered the duduk.

There is a band called Morning Calm. It’s a deep cut in your discography. What happened to the project?

When I came back to Paris in the summer of 69, I met an Irish guy who was busking. His name is Leo Gillespie. There also was Gerry Field, an excellent young violin player from Chicago. We played in the streets of Montparnasse for a couple of months, just before the founding of Gong. Busking was a very good experience for me. People are passing by and are not necessarily listening to you. You need to have something seducing to attract them. Leo was very good at that. He improvised all of his lyrics. We eventually went into a studio and recorded an album. The guy who brought us in was gentle and helpful… He sold the tapes to the label Barclay and gave the project the name “Morning Calm”.

It was not our choice. Years later I discovered the album existed. I didn’t even know. I met Leo and Gerry after this, but never carried on with the project.

There is an album from 1971 called ‘Obsolete’. It is by Dashiell Hedayat together with Gong. Do you remember recording it?

It was shortly after ‘Camembert Electrique’. We recorded it at the Château d’Hérouville [also known as Strawberry Studio], a beautiful place where we also did ‘Camembert Electrique’. Daevid did ‘Continental Circus’ there, but I did not participate in this one. A lot of famous musicians recorded in that studio: Pink Floyd, David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Elton John… Dashiell Hedayat was a writer. A very tripped out guy, who once got lost in the sea during a trip. Luckily he was rescued by a fisherman. He was one of the first guys to sing Rock in French. The album was very appreciated. I played the electric saxophone, which sounded a bit like a harmonica… Pip Pyle played the drums. Daevid Allen was on gliss guitar. So you have the original Gong Line-Up. The album was fun. Some critics say it is historically important. But then Hedayat dropped the idea of being a musician and became a famous writer. He had a bestseller with Il Monsignore.

After the departure of Daevid Allen and Steve Hillage in the mid-70ies Gong turned more to a Jazz Fusion style in the likes of Weather Report. How did this influence your work?

The Gong style and mythology was due to Daevid Allen. When he left, for personal reasons, we still had the name, but the tendency was more jazzy. The album ‘Shamal’ of 1975 is the reflection on Gong by Pierre Moerlen, Mike Howlett, Patrice Lemoine, the violin player Jorge Pinchevsky and me, plus guests Mireille Bauer, Miquette Giraudy and Steve Hillage.

Nick Mason of Pink Floyd produced the record. The sound is very good. And the album turned out to be quite coherent. Afterwards Steve Hillage moved on and formed his own group and we did the album ‘Gazeuse!’ with guitarist Allan Holdsworth, an excellent Jazz guitar player who wrote pieces for the Tony Williams Band. That was a huge thing! He refused to go on a US Tour and decided to stay in England because of the good beer (was he joking…)

Tony Williams personally was phoning from the USA to persuade him to re-join the band. But Allan didn’t want to. I was amazed. Gong was famous, but Tony Williams was ten times bigger! When my son Gregory was born, I left the band and with his mother Niquette-Christine we moved back to France. It turned out to be a good idea. The 80’s came and the focus was more on Punk. If I had stayed in England I would have had some problems.

What did you do musically after your departure?

I came back to Paris and I started to work as a studio musician. I also got to play with Jacques Higelin, an extraordinary poet, singer, and showman. We played in the Casino de Paris for four months. There were a thousand people every night. It was crazy. In this time I also recorded my first solo album ‘Bloom’. I did four solo albums. They correspond to the four elements ‘Bloom’ (1980) was earth. ‘Fetish’ (1990) is the one about fire. ‘Zeff’ from 1992 means wind or air. ‘Fluvius’ from 1994 is the story of a river.

Nowadays you are known for your work with Hadouk. How did this project come to life?

I had a group called Faton Bloom with Faton Cahen, the former pianist with Magma. We did a nice album together and played several gigs. I was playing a lot of saxophone, more in Jazz-Rock style. But at this point I became more interested in acoustic instruments like bamboo flute or the ‘Zeff’ (harmonic flute) and eventually duduk. Then I met my friend Loy Ehrlich, whom I knew since the early days of Gong. He had worked with African musicians like Toure Kunda and Youssou N’Dour. He was playing a Moroccan Gnawa bass, the Hajouj.

For our first album as a duet we put together the names of our instruments and came up with Hadouk (hajouj-doudouk). We met Steve Shehan, a fantastic percussionist and worked together as a trio for nearly 20 years, made seven albums mainly on Naïve label and got awarded the Victoires du Jazz. We played in many countries: in Asia, Africa, Europe, South America, USA, Canada.

In 2014 Hadouk became a quartet with Eric Löhrer on guitar and J.-L. di Fraya on drums. Two albums were released for the Naïve label, ‘Hadoukly Yours’ and ‘Le Cinquième Fruit’.

“To melt different cultures”

What is the main concept behind Hadouk?

It’s a world music concept. The idea is to play instruments from different countries and try to play them in another way. I love Armenian music, but I am not Armenian. If I had taken an Armenian master and tried to play that music, I just would have been a guy trying. The duduk is a very rich instrument although it is just a cylinder in apricot wood with ten holes of play. Its beautiful sound comes from a large double reed called “khamish”. It drove me to create my own style and melodies, somehow jazzy, but not only. The main idea: to melt various cultures, towards a personal approach of global world music.

It is impossible to cover your whole discography. Is there a specific work, which makes you understand why you became a musician?

It is a very rewarding thing. With Gong we performed large gigs, and smaller venues too. Every gig brings you something. It really helps you to live, you are happy to have given to the audiences. That’s a warming feeling, indeed. Then came some lucky opportunities: In 2001 I was invited by Djivan Gasparyan, the Master of duduk. He invited me to play a festival in Armenia, with my friend Patrice Meyer on guitar. Very interesting to play in front of an Armenian audience! Two years later he invited us to Russia. The band was composed of ten musicians from diverse countries. We played the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. A Russian TV station broadcasted it. We played a tune of mine called ‘le Serpent d’étoiles,’ Djivan improvising over it. You can hear it on YouTube. A sort of recognition…

In 2010 we recorded on the label Naïve a jazz duduk album called ‘Nuit d’Ombrelle’ with the guitarist Eric Löhrer (who also played in the Hadouk Quartet). I like this album very much.

Around 2017: concerts with the trio “Le tour du monde en 80 minutes” (Jean-François Zygel, piano, Joël Grare, percussions).

2018/2020: concerts in Taïwan with “Round About Duduk” and recording “The Yangqin and the Wind” (Cezame) with the Taïwanese yangqin player Yaping Wang.

Is there anything you take your inspiration from?

I enjoy reading and writing poetry. I have two books of my sonnets published. Another thing I dig is: spinning tops. I am crazy about them. We created a YouTube-channel with videos called bloomditop. Spinning tops are cosmic things. They exist in all countries at all times. They reproduce the universal movement and are toys all around the world.

Are there any albums you consider your favorites?

Many albums! Of course ‘Bird and Dizz’. Hearing Stan Getz made me pick up an instrument. He has an awesome record called ‘Focus’. The Beatles’ music is important to me, too. I like melodic things. I am a fan of Jeff Beck’s ‘Blow by Blow’. This album always followed me. There are so many records I enjoy listening to: the flute sonatas of Johann Sebastian Bach, Bela Bartok, Ravel, Stravinsky, classical Indian Music… But in fact I am a Jazz guy. Improvisation and swing still get me.

How do you feel about being an influence for other musicians?

Before I started duduk, this instrument was played mostly for the beautiful Armenian traditional music, by Armenians (or french Armenians). I tried to invent my own style. I did not copy the traditional players (although some dudukists gave me some advice) and now some young people follow my tracks. I feel like a sort of pioneer in my way, humbly proud of having helped to create a new style of world music. It is my contribution.

Max Ritter

Duo Alexandre Cellier and Didier Malherbe | March 25th 2023 at La Chaux de Fonds (Switzerland)

Headline photo: Didier Malherbe in 1970

All photos are from private collection of Didier Malherbe | All photo materials are copyrighted by their respective copyright owners, and are subject to use for INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY!

Didier Malherbe Official Website

Gong interview with Daevid Allen

Tim Blake interview

Steve Hillage interview

Gong are releasing a new album – ‘Rejoice! I’m Dead!’. Interview with Kavus Torabi (vocals/guitar)

Fantastic interview, especially spinning tops!