Tom Carson and the Lazy Eggs and Fiddlers Music Store | ‘60s Garage Rock from Detroit, Michigan

Collectors of private press albums and singles released during the progressive rock ’70s—records now discovered via unauthorized digital represses, most infamously by the defunct Radioactive Records shingle—mistakenly interchange the names of Detroit musicians Tom Carson and Tommy Court as an artistic Janus: two faces of a singular person who, in the summer of 1974, released music under the Phantom mononym: an ethereal Motor City musician masquerading as a three-years dead Jim Morrison. Courtesy of questionable press kits and liner notes composed by pirate impresses, today’s vinyl-to-digital collectors also believe the names of Ted Pearson (born Earl Theodore Pearson) and Arthur Pendragon (Pearson’s later legal name change) mentioned in the Phantom mythos were, once again: Tom Carson.

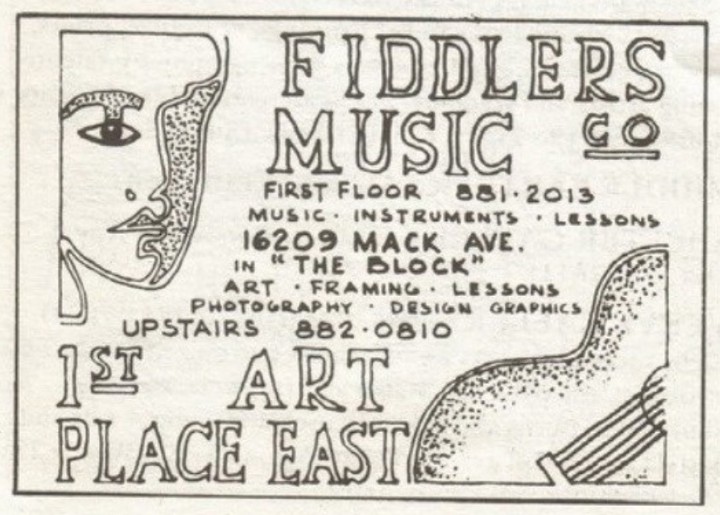

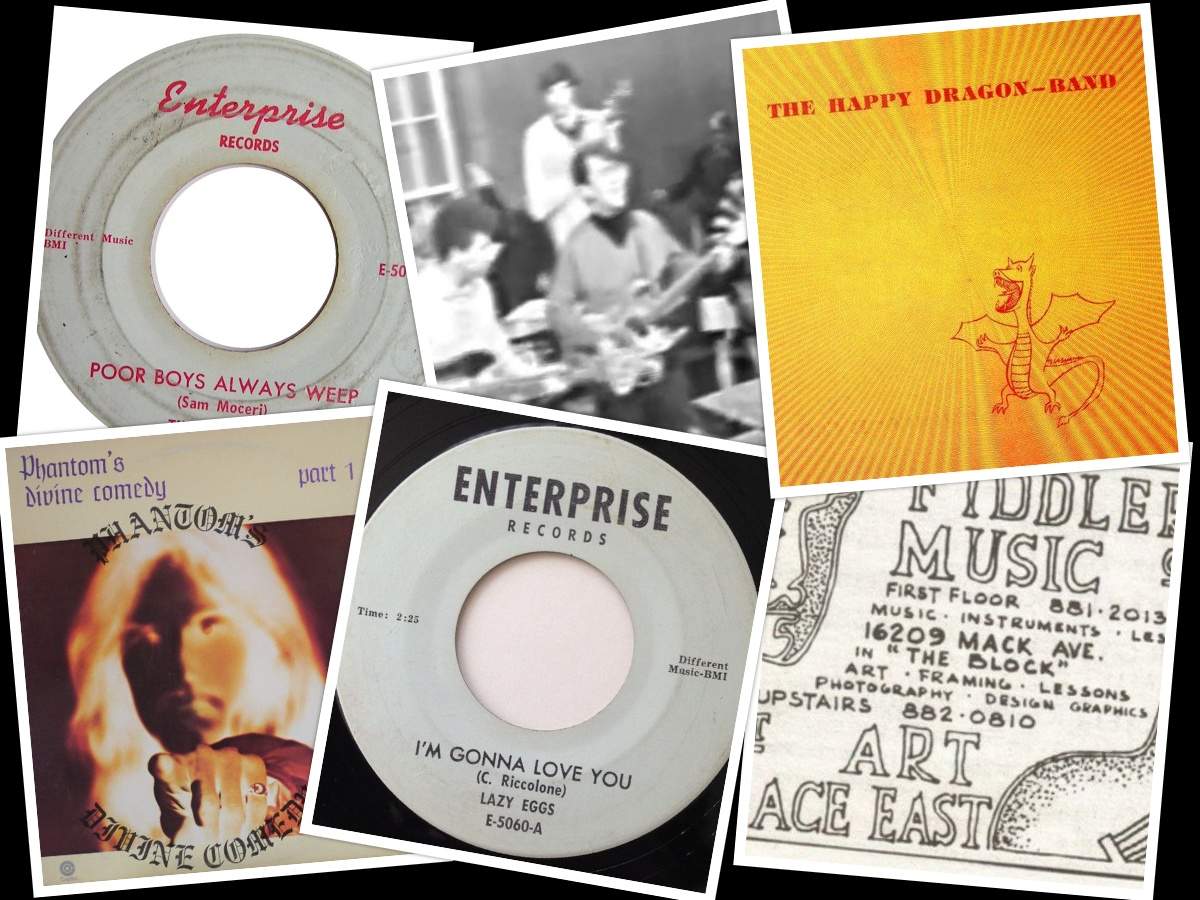

Oh, what a tangled web the digital content warriors of the World Wide Web, weave. For neither are pseudonyms of the other and are, in fact, three different people—and not as mysterious as once believed. As Scott Strawbridge, Tom Carson’s longtime friend, business partner at Detroit’s Fiddlers Music, reasoned, “While [the fans] got the story wrong, it’s really cool that people have the sense that ‘something important’ was going on then—when it really wasn’t”.

Ted Pearson’s longtime friend and creative associate, Chris Marshall, a guitarist with the Detroit bands White Bucks (from the Bob Seger/Mitch Ryder-axis), Pendragon (Pearson’s next band), and Powerplay (Pendragon without Pearson) recalls that non-importance. “I don’t recall too much, and I don’t think many do, about the whole Walpurgis or Phantom thing. Just that Ted sounded like Jim Morrison. I don’t remember it being that big of a ‘buzz’, really. Walpurgis [or their previous incarnation as Madrigal] weren’t a major band on the local scene”.

While Tom Carson—or Tommy Court for that matter—wasn’t responsible for the mistaken identities and assumptions of his career, it is pleasing to see that Carson, unlike most regional, private press musicians of yore, shattered the yokes of his limited, Northeastern and Midwest U.S. awareness. Sure, musicians had their music stolen for the sake of marketing pirate copies of the Phantom’s music; however, there’s another side to the denarius: the theft blessed Tom Carson—the founder of the Lazy Eggs—with a shot of international stardom as the assumed mastermind behind the oft-pirated ‘Band’ by the Happy Dragon and ‘The Lost Album’ by Phantom.

While the electro/synth-pop-driven former is familiar to vinyl collectors by the Happy Dragon Band misnomer, the latter is actually an obscure Detroit proto-metal concern: Walpurgis. Well, Walpurgis were responsible for ‘Phantom’s Divine Comedy: Part 1’, aka the “Jim Morrison’s solo album”. ‘The Lost Album’—marketed as the missing “Part 2”—is, in reality: a pirated demo tape recorded in 1977 at Fiddlers Music by Arthur Pendragon for his next band, the AOR-driven project, Pendragon—which many critique as “a rough-hued Springsteen and less Morrison”.

According to keyboardist Russ Klatt, the grinder of the Hammond B3 as “Z” on the Phantom’s 1974 rock opera, Detroit impresario Ed “Punch” Andrews—with the band’s knowledge (rounded out by bassist Harold Beardsley and drummer James Roland) and support—christened the Bob Seger-shadowed hopefuls with the Phantom moniker to quickly market the album as being recorded by Jim Morrison.

Chris Marshall confirms Klatt’s insight. “Punch [Ed Andrews] was a smart guy and worked hard for everyone. I never heard a bad word about him. I think he was honest in that he just came up with a way to market the record, quickly. Again, Ted—not on purpose—did sound like Jim”.

Drummer Ron Course, who played on Pendragon’s earliest, pre-1977 home-based demos, also remembers Ed “Punch” Andrews’s loyalty to his artists. “Some people thought Punch was ripping them off. Nope. Punch, being the smart businessman he was, invested their money—each person. He set the Silver Bullet Band up, for life. He took care of everyone”.

“Punch treated Bob like a son; like an overprotective dad”, reiterates Russ Klatt. This is a point also made by Mitch Ryder of the Detroit Wheels in Dave A. Carson’s all-encompassing rock tome on Detroit’s music scene, ‘Grit, Noise and Revolution’,—that Ed “Punch” Andrews treated Bob [Seger] like a son.

Scott Strawbridge, who performed as one of the ‘mysterious musicians’ on the Happy Dragon effort, as well as served on the staff of Fiddlers Music as a producer and sound engineer, attests that the Phantom isn’t whom everyone believes. “I can tell you Tommy [Court] has a unique singing voice and it doesn’t sound anything like Jim Morrison. He doesn’t look like Jim. I don’t think he’s ever covered a Doors song in his life. And I’ve known him since our first school, musical endeavors in the 8th or 9th grade. His music tastes probably don’t even go in that direction. Googling, one day, I came across, in a book about Jim Morrison, the name ‘Tom Carson’ being mentioned and he was ‘Arthur Pendragon’ and behind the Phantom project. I can tell you Tom Carson and Tommy Court are not the same person”.

So, where is the mysterious Tom Carson these days?

“I haven’t seen Tom personally since I left Fiddlers in the late seventies, but we were good friends for many, many years,” Strawbridge recalls. “In fact, his mom died and I needed a place to stay; he let me stay in his home for a year and a half; we sailed the Bahamas and the Caribbean together. We made music together; we produced a record and flew down to Criteria [Studios] in Miami and mixed it there. We were not just coworkers or me, his employee: we were very, very fast friends. And we became business partners. While a capable musician and guitarist, again, I can tell you that Tom’s, as well as Tommy’s, vocal talents were very limited and there is no way possible that Tom Carson—in any way, shape or form—could have imitated Jim Morrison with any success or any credibility. No way, absolutely not. As for where he is, today, the last I heard Tom was living in Ontario where his family is. We used to go there in the summers back in the day. He left Fiddlers and moved to other interests outside of the music business”.

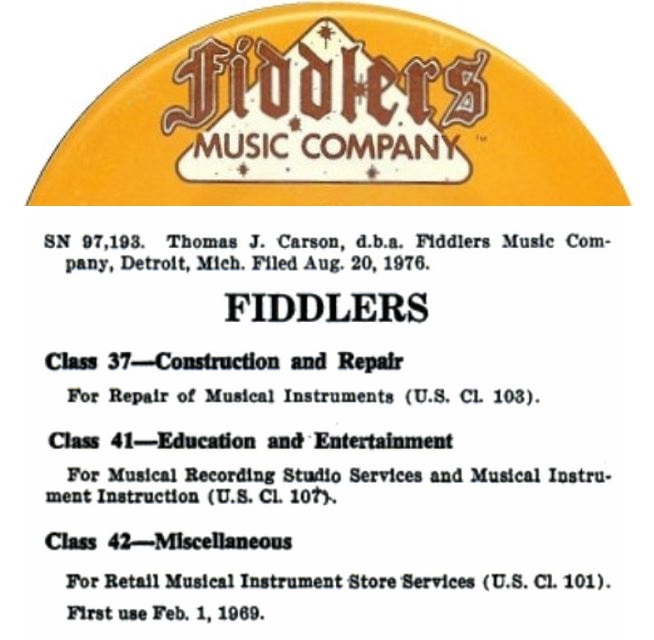

The question is: Where was Tom Carson . . . before Fiddlers Music appeared on the “Detroit side” of Mack Avenue near Outer Drive (the city of Grosse Pointe sits on the other side)? What is the story behind the mysterious Fiddlers Records’ logo emblazoned on those original, 1978 pressings of the Happy Dragon effort—500-unit copies now demanding several hundred dollars in the international online-marketplace?

Another question: How did a late ’70s demo recorded at Fiddlers Music by an obscure AOR band cross an ocean for a pirated release on Italy’s Ghost and Flash impresses (1990 vinyl and 1997 compact disc)? Scott Strawbridge surmises whomever purchased the “carcass” of Fiddlers music from Tom Carson began liquating the assets; they went through the studios’ tape library, seen the “Pendragon” name, realized what they had, and decided to make money off the Phantom mythos—from something, at that time, wasn’t seen as a recording of any significance. That tape’s roster-connections to the Happy Dragon then propelled Tommy Court’s long-forgotten album to international awareness—and created a product for the pirating marketplace.

As for Tom Carson at the center of the musical storm: he isn’t all that mysterious.

Thomas Carson—like the career-paralleled James Osterberg with the Iguanas and the Prime Movers, and Robert Seger with the Decibels, the Town Criers, and Doug Brown & The Omens, and Glenn Frey with the Subterraneans, the Four of Us, and the Mushrooms—was just another starry-eyed teen on Detroit’s early-to-late ’60s local scene. His Fiddlers Music, while initially incorporated as a music store in 1970, later added recording and distribution services to Detroit musicians, up until its early ’80s demise.

“In addition to working at Fiddlers,” says Scott Strawbridge, “I also worked at Cloudborn Studio from time to time; however, I was not a staff person there, as I was at Fiddlers. At both studios I worked with deMar [Mike deMartino, credited on Phantom: The Lost Album]. Fiddlers served as the ‘demo studio’; we had projects that would demo there, evolved, and then moved to Cloudborn—where we worked ‘at the big studio down the street’. That material was released on a variety of labels, some on Fiddlers”.

Mike deMartino, reflected on his pirated-credit on the Fiddlers Phantom tapes. “I don’t remember playing piano [on those sessions], but it’s possible I did. The musicians listed [Gary Meisner, Dennis Craner, and Jim Badanjek] were connected through Fiddlers. They did sessions there all the time. [A few years later, in 1983 on two 45-rpm singles] I did work on a project called ‘Pendragon’ when I was at Cloudborn as a recording engineer. I did work with Tommy Court; I sang and played keyboards with the Happy Dragon”.

“It could be anyone on those Pendragon tapes, really. Fiddlers had a cataloging system, but it was a shoddy one that wasn’t enforced. Sometimes, you just didn’t fill out the forms,” Scott Strawbridge completes the thought.

“Here’s a bit of the back-story between Fiddlers and Cloudborn,” Strawbridge continues. “Tom Carson was a rock ‘n’ roll guitar player in the Lazy Eggs with Clem Riccobono and Gary Praeg. Gary founded Cloudborn Studios. Meanwhile, Clem, Sam Moceri, also of the Lazy Eggs, and Tom were down the street dealing all this equipment out of Fiddlers, which was a music store at that point. The catalyst of Fiddlers going into recording work was Tascam coming out with the half-inch eight-track deck, which was the solution to rent out studio time at an affordable rate to emerging musicians for them to make quality demos”.

Mike deMartino, as well as former Sincerely Yours, Wilson Mower Pursuit and Pendragon guitarist Rick “The Lion” Stahl, recalls that United Sound not only mastered tapes: they also had a record lathe. The process was that R&D demos were cut at Fiddlers, recorded for release at Cloudborn, and then mastered at United Sound. And sometimes United Sound cut the vinyl for a variety of local, private-press labels, such as Stahl’s Pendragon on their own Dragon Lady-impress.

“Fiddlers is where I came to known Tommy Court,” continues Scott Strawbridge. “We built the studio, together, and we were able to tap into all of the equipment that was for sale at Fiddlers. Along with the working studio and all the instruments, we were able, for $25 dollars an hour, to lock the door at night and musicians owned the place”.

One of those musicians was the infamous Phantom, aka Arthur Pendragon, with his post-Walpurgis/Phantom concern: Pendragon. The Euro-pirated ‘The Lost Album’ credits Tom Carson on guitar and lead vocals, Gary Meisner on guitar, Mike deMartino on keyboards, ex-Catfish and Rockets’ Dennis Craner on bass, and the Rockets’ John Badanjek on drums; they, sans Arthur Pendragon, also appear on the Happy Dragon project devised by Tommy Court. Well, so the impress-pirates, say.

“That list of musicians [on the Phantom project] just doesn’t jive,” Scott Strawbridge advises. “I know all those cats. And they all had their own projects and helped each other on their own projects [cut at Fiddlers and Cloudborn]. Yes, we all assisted Tommy on the Happy Dragon project. And again, I have to stress that we were not the Happy Dragon. Tommy is the Happy Dragon and we were just studio musicians”.

So, Tom Carson had a “Wrecking Crew” like Phil Spector?

“You have to realize that those guys were the Fiddlers’ equivalent of Motown’s the Funk Brothers,” Strawbridge tells us. Mike Skill and Jimmy Marino of the Romantics did a lot of session work for us during those years. For $25 bucks a piece an hour, they could lay down a rhythm you could set a chronometer to. So, it’s even possible they’re on the Pendragon tapes. I’d also have to add: Gary Meisner was a luthier down in the woodshop and an incredible guitar player in his own right [most famously with blues musician Pine Top Perkins]. Dennis Craner worked in our lesson rooms and taught bass at Fiddlers [and became a locally-noted chef]. deMar was behind the boards and worked sales in our piano room. Then I was in the studios and doubled on the sales floor”.

Most of those locals who walked through those Fiddlers’ doors, such as Holy Smoke and Jett Black, remained unknown outside of the Midwest, even Michigan. A few, such as Adrenalin, flirted with minor national recognition (on Rochshire and MCA), while others became nationally known, such as Joe King Carrasco and the Crowns. Even famous musicians, such as Willie Dixon, needing to record incognito, recorded at Fiddlers. Tom Carson’s humble dream of owning his own music store transformed into more than just a store to pick up a pack of strings or replenishing drum sticks.

“Fiddlers worked with the Rockets and with Catfish Hodge [released two, early ’70s blues-jam albums and three singles on Epic; while not a member, Tom Carson wrote lyrics for and toured with the band],” reflects Scott Strawbridge. I also worked with Gene Simmons [of KISS] and he recorded quietly and privately on some demos. We R&D’d a lot of music back in those days. At the time I—all of us—didn’t think much of it. But now, thinking back to all of the folks that walked through those doors: Fiddlers was a huge hub in the Detroit and Midwest music network—and a significant hub in the national scene. The label had an extensive artist roster: deMar [Mike deMartino] and I worked on all of them. Tommy [Court] did a couple, as well, before he went on tour to be the soundman for the Rockets. When it came to sound and electronics in Detroit: Tommy was the man”.

And Tom Carson, across the three floors of Fiddlers Music, was “the man” who supported Detroit’s cash-strapped musicians with affordable equipment and recording.

“The first floor was equipment sales, the second floor was lightning and sound, and the third served as the recording studios,” Strawbridge recalls. The second floor also had a luthier studio and lesson rooms. We had about 150 students a week coming through the doors. Fiddlers also had a product line: Superstar Products. We made and sold guitar, drum and cymbal polish, along with padded guitar slides, amp protectors, and various little accessories that were wholesaled across the country. Tom staffed-out the in-house assembly line with high school and college kids. We also had a big endorsement deal at the time with famous rock stars for our ‘Axe Wax’ line. Tom Carson was a smart businessman; he had a gift and he made a lot of money on that retail wholesale business unit. The retail unit kept the whole business going”.

Tom Carson—as evidenced by his credits on the Happy Dragon and Pendragon project—still found time to produce, as well as perform guitar and backing vocals on, sessions at Fiddlers.

“In this one instance, Tom came up with this ‘one hit wonder’ idea: and it’s where our business relationship fell apart,” Strawbridge wrap up his Fiddlers memories. We were all involved in it: Tommy, deMar, Clem [Riccobono], and Sam [Moceri].

“After Princess Di [Diana] was killed and disco was coming up, Tom had an inspiration and came up with this song, “Sweet Lady Diana”, a disco-dance song that we mocked-up at Cloudborn. We had Lamont Johnson, a well-renowned session bassist, play on it, along with Marcus Belgrave [Ray Charles, the Temptations, the Four Tops] on trumpet. We went first class all the way. We took it to Criteria [Studios in Miami; Eric Clapton famously recorded there in the ’70s] to mix. It didn’t go anywhere and it was a total flop. And that financial disaster caused the business relationship between Tom and me to fall apart”.

There was life, however, after Fiddlers Music for Scott Strawbridge. He transitioned to concert production and management in South Florida in the ’80s, working on the internationally-known Reggae Sun Splash festivals, as well as recording the works of Jaco Pastorius and reggae stars Toots & the Maytals, Eek-A-Mouse, and Yellowman.

In a business model akin to jazz musician and electronics guru Maurice “Moe” Whittemore discovering a unique business opportunity in creating an affordable studio environment to local Indianapolis, Indiana, musicians—not only for recording, but also releasing albums and singles with a private press-imprint though his 700 West Recording (most famously with the recently, compact disc-reissued proto-metal concern, Primevil)—ex-Lazy Eggs’ Tom Carson found his niche in the Detroit, Michigan, music scene.

“By the mid-’60s, as black and white cathode ray tube images of U.S. television’s highly-rated ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’ introduced Detroit’s teens to jangly Mersey Beat guitars, the stars of early rockers, such as Bill Halley and the Comets and Joey Dee and the Starlighters, dimmed. Changing with the times, the early ’60s soul and R&B-influenced sounds of TC and the Good Guys transformed into the Beatlesque the Lazy Eggs. Impressed with their writing and live performances, Carson’s Eggs signed a management contract with Bob Swartz. While they never shared a stage, Swartz also managed the earliest beginnings of Bob Seger’s career with his band, the Last Heard.”

“I was one of the original members of the Lazy Eggs, back in 1959”, Sam Moceri recalled in the defunct digital pages of ‘60sgaragebands.com’. “The original band was Tom Carson on lead guitar, Tom Pointe on rhythm guitar, Clem Riccabono on bass, and me, on drums. We started out as TC and the Good Guys.

“When I returned to the band in 1963 on keyboards, we had two other players: Gary Praeg on rhythm guitar and Ron Koss [then noted for touring and recording with Wilson Pickett, Merv Johnson, and Hank Ballard, as well as his Motown session work] on lead guitar. Our first big bar gig was at ‘The Red Carpet Lounge’ on Warren and Outer Drive in Detroit, where we replaced Bob Seger, who moved to ‘The Roostertail’ [Lounge]”.

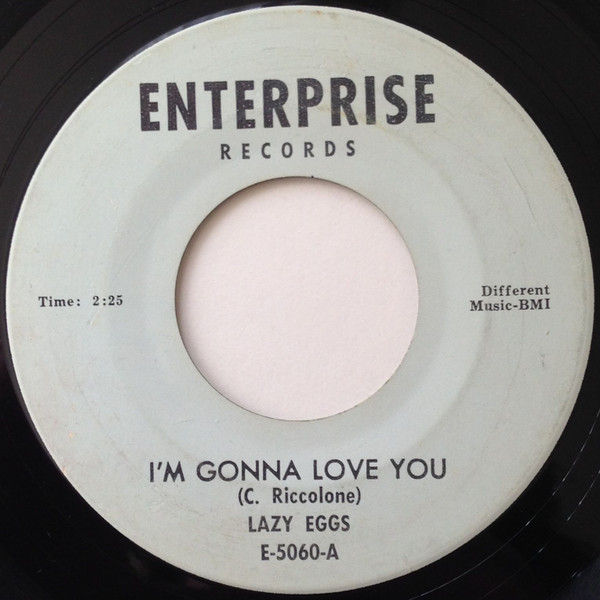

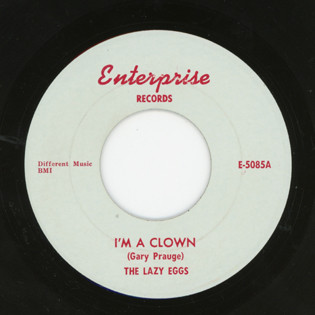

Carson and associates (another member through the turnstile was drummer Bob Krause; each sang their own compositions) cut their first 45-rpm single, “I’m Gonna Love You b/w As Long as I Have You” (E-5060; both composed by Riccobono) for Detroit’s Enterprise Records in 1967 (not in 1965 as web-cataloged). Their second single, “I’m a Clown b/w Poor Boys Always Weep”. (E-5085; Praeg composed the A-Side; Moceri the B-Side) appeared shortly after. (The single, “My Baby Don’t Care b/w The Hammer Song”, released in 1968 on the Sunspot label oft-compilation confused with the Detroit Eggs is a different group: one led by Sid Herring; he later formed Watchpocket, an early, Southern Rock concern with Steve Cropper, known for his work with Stax Records’ house band, Booker T. & the M.G’s, as well as Otis Redding.)

“I’m a Clown b/w Poor Boys Always Weep” debuted on Ontario’s CKLW-AM “The Big 8” on March 6, 1967. Achieving a minor placing on Detroit’s “Keener 13” WKNR-AM’s Top 40 chart, the single peaked at #28 on CKLW-AM, and at # 15 and #11 on Flint, Michigan’s smaller WTAC 600 AM and Ann Arbor’s WPAG 1050 AM, respectively. The chart success led to WKHM/WKNR’s Robin Seymour (later of CKLW-AM) hosting the band’s performances of both sides during a March 11, 1967, episode of ‘Swingin’ Time’ airing on CKLW-TV’s Channel 9.

However, by 1967, the roar from the screaming teens enamored with Beatlemania dissipated in the proto-prog grooves of ‘Sgt. Pepper Lonely Hearts Club Band’. The Fab Four’s British contemporaries of the Dave Clark Five, Gerry and the Pacemakers, and Herman’s Hermits no longer invaded the charts. The “hard blues” of Led Zeppelin sounded like clarions: bands had to adapt or die.

It had been eight years since Tom Carson’s TC and the Good Guys first appeared on the Detroit scene. Now, the Lazy Eggs were—as fellow locals Bob Seger and the Last Heard, Ted Nugent with his Amboy Dukes and Jim Osterberg with his Stooges—ready to take their first steps into the national marketplace. Unfortunately, the local radio and TV support afforded the Lazy Eggs didn’t translate to either of their Enterprise releases receiving national distribution. By then, the Eggs’ fellow teen-garage scenesters the Kwintels dropped their British-inspired pop sensibilities, transforming into the harder-edged Tea to share stages with Iggy Pop (and, under the management of Ed “Punch” Andrews, stepped on national stages as 1776). Teen garage-rockers the Ascots split and morphed into the Electric Blues Band and the Toad and the Mushroom, each sharing stages with the MC5. Even the Detroit Vibrations led by drummer Rick Stevers dropped their cover sets and their own pop-minded originals to turn up the amps as Frijid Pink—and a nascent Led Zeppelin opened for them at Detroit’s famed ‘The Grande Ballroom’.

As is the case with most of the lost and forgotten garage bands of the ’60s issuing private press 45s, which we now enjoy on video hosting sites and overseas compact disc compilations, the Lazy Eggs never adapted to the new, British-based “hard blues” style. According to Sam Moceri’s reflections, the Lazy Eggs split in 1972.

Tom Carson, while organizing the opening of Fiddlers Music in 1970, continue to perform with Bob “Catfish” Hodge in the Catfish Blues Band.

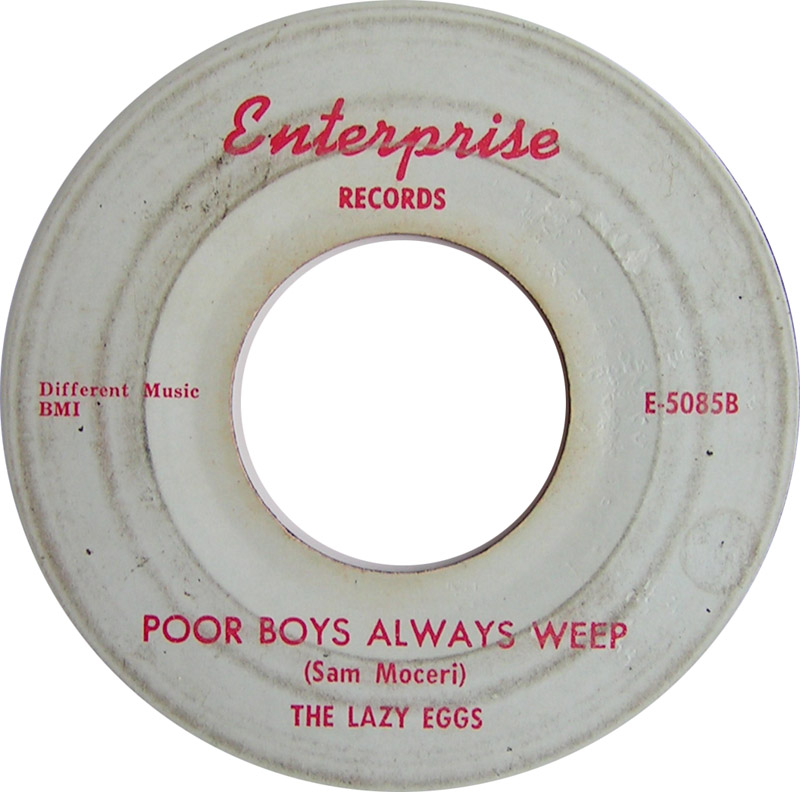

Prior to their becoming Lazy Eggs, Gary Praeg and Ron Koss gigged on Detroit’s local stages as members of the R&B flavored the Pacesetters (not to be confused with the West Coast soul group that cut “I’m Gonna Make It b/w What About Me, Baby” in 1968 on New Orleans’ Minit). The Pacesetters, also featuring drummer Vin Scalabrino and future the Rockets’ bassist John Fraga—inspired by Major Lance’s chart-topping dance-craze hit, “The Monkey Time”—cut the one-off 45-rpm/7” “The Monkey Whip b/w Around the World” (CT-3476), released on the Detroit-based Corre-Tone on September 14, 1963. (Both sides were written by famed Motown writer-arranger, William Witherspoon.)

Along with bassist Angelo Palazzolo and drummer Chris Birg—both later Lazy Eggs’ members—Gary Praeg formed a new trio; by 1970 that trio, Katzanjammer, replaced Bob Seger as the house band at Detroit’s historic Roostertail Lounge. Praeg’s later establishment of Cloudborn Studios led to his working with U.S. R&B legends Anita Baker, George Clinton and Bootsy Collins, and Keith Washington, just to name a few. He also worked with Ed “Punch” Andrews for Capitol Records’ Barooga Bandit and Tommy Court’s disco-inflected Hott City project. Returning to recording his own material at Cloudborn, Praeg released ‘Falling in Love’ (1981) under the Shivers moniker—with assistance from Ken Sands, who produced many Motown acts, Marvin Gaye in particular. Released on A&M via Private Stock Records, Praeg counted Blondie, Detroit’s Brownsville Station, and a solo bound Frankie Valli as labelmates.

Unlike the Pacesetters and the Lazy Eggs, Ron Koss’s next band, Savage Grace, reached the U.S. Billboard Top 200 in 1970 with the single “Come on Down” issued on the Reprise label; after releasing a second album, Savage Grace split in 1971. Katzanjammer reformed, somewhat (with Lamont Johnson on bass) in 2004 as the smooth-jazz outfit Dove Grey, releasing the album, ‘Anything Is Possible’.

Drummer and keyboardist Sam Moceri had an unusual second job: serving as a Detroit police officer, a career began while still in the Lazy Eggs. Sam Moceri and Tom Pointe passed away in 2018, while bassist Clem Riccobono died in 2014. Originally thought as currently retired from the music business, as we went to press, we’ve come to discover both Tom Carson and Gary Praeg are in poor health and were unable to contribute their insights to this article.

Reuniting in the late ’90s, Savage Grace posthumously released their third album, One Night in America, in 2006— after the 2004 passing of Ron Koss.

In addition to their fans’ YouTube uploads, the Lazy Eggs’ best-known single, “I’m a Clown”, lives on via ‘60s retro-garage rock compilations, most recently on the 2006-issued, fifth volume of the Australian-released ‘Wyld Sydes’. “Poor Boys Always Weep” lives on courtesy of Tony the Tiger’s ‘Fuzz, Flaykes & Shakes’ garage compilation series (2002).

So, when reflecting on Detroit’s explosive, inspirational music scene of the mid-to-late ’60s: for every Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band, there’s Tom Carson and the Lazy Eggs in the dusty, vinyl shadows. And Tom’s career wasn’t all that wild or mysterious. He was one of the Motor City’s many, necessary gears that grinded away to create the cherished “Detroit Rock City” we know today.

R.D Francis

Garage Hangover article

Phantom | Interview | Keyboardist Russ Klatt of Phantom’s Divine Comedy

Thanks Francis for this ovscure article about an obscure music scene. I found a few things here that are new to me. Thank you !

Sorry for the typo, the problem with the smart phone. I think you know what is meant.

RecordStoreDay 2023, April 22, the Happy Dragon Band LP plus 2 unheard tracks will be officially released (45 years late).

Not a bootleg but rather from the original masters of Tommy Court with more to come on Org Records.