Axolotl | Etienne Brunet | Interview

Etienne Brunet is a French multi-instrumentalist who has been active for more than four decades, always experimenting and breaking down barriers.

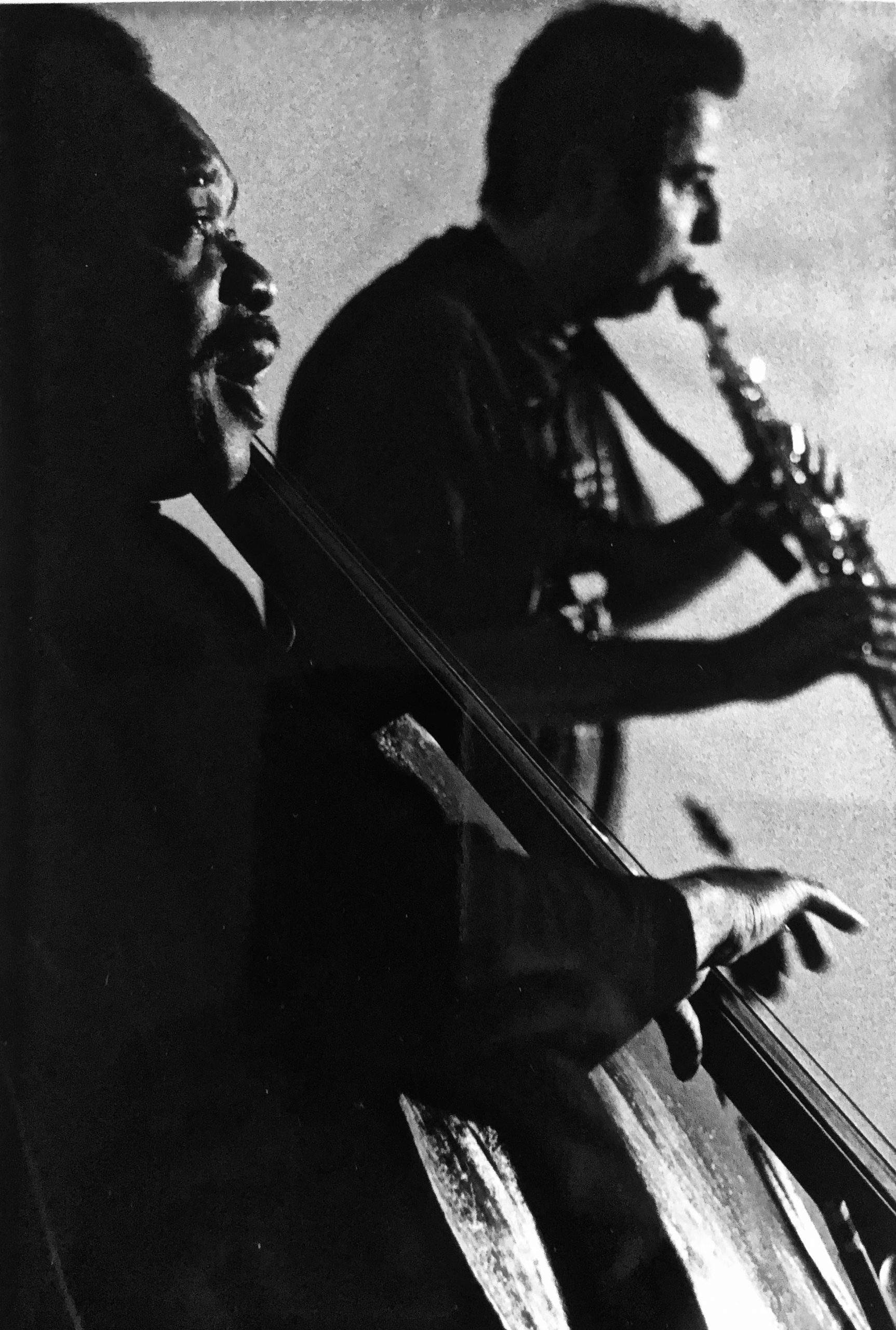

In 1981, he co-founded the free improvisation trio Axolotl (with Jacques Oger and Marc Dufourd), which released two albums. In the following years, he performed with a really wide variety of musicians, including Jac Berrocal, Anthony Coleman, Wayne Dockery, Jean-Jacques Birgé, Jean-François Pauvros, Guillaume Loizillon, Erik Minkkinen, Jean-Jacques Avenel, Sunny Murray, Yasuaki Shimizu, Emiko Ota, Laurent Saïetm, Cornelius Stroe, Fred Van Hove, and others.

At the end of March SouffleContinu Records will release ‘Abarasive’. More news will follow.

“I had learned that nothing is ever acquired”

How did you first get interested in music? Were either of your parents musicians?

Etienne Brunet: My mother had died when I was 6 years old and I had been educated for two years with her sister in Nice. She was a chorister at the opera and she took me often to see operas. I hung out backstage and was hired to be in the children’s choir of Carmen which was performed in the winter and summer season. The theme: “Love” and “Death”. I was overwhelmed and completely deranged. I didn’t understand anything anymore. What is love? What is death? Sixty years later I still ask myself the same question. This opera was very intensive. The lights, the sets, the orchestra that vibrated on the stage, the singers who shouted, the dancers, the extras in costumes… I never got over it. Never. I was traumatized for life. Then I did six years of “music pension.” I was deprived of music in the big freezing dormitories of the Parisian suburbs. I couldn’t fall asleep so much I heard music in my head. I felt really bad.

Was there any particular moment when you knew you wanted to become a musician?

I went to Mexico when I was twenty. I stayed there for a year. I had quit my studies. I had made a lot of money the year before. A stroke of luck for a 19-year-old guy. I didn’t care about the music. I wanted to make the revolution. Wipe capitalism off the face of the earth. But I quickly realized that things were not so simple. I was an excited little prick, thinking I knew everything. Latin America immediately taught me the harsh reality. I was friends with survivors of the Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico City in 1968. I learned a lot there. I was traveling from town to town all the time. I remember like it was yesterday: I was in San Cristóbal de las Casas in Chiapas. An Indian was playing a plywood fiddle in the street. He was playing music that was unlike anything I knew. The guy stopped, looked me in the eye, and handed me his violin. He wanted to sell it to me for a pittance. I said no. I ran away, furious. After five minutes, I realized that this was the chance of my life. I absolutely needed this violin. I retraced my steps, but the guy was gone. Shaman has flown away by magic. At that moment I had the enlightenment that I will dedicate my life to music.

Who would you cite as some of the main influences?

The social revolution would never happen and I wanted to play something powerful, explosive, revolutionary. I only listened to free jazz and psychedelic rock. At the time, it was the aesthetic revolution, the musical insurrection. I was berserk even though doubt had crept into my mind. I had come to hate classical music.

You took lessons from the great Steve Lacy, what were some of the most important lessons you got from him?

With Steve Lacy, I had learned that I would have to study all my life. I had learned that nothing is ever acquired. I had learned that only the constraint of knowledge gave the freedom of the game and not the reverse. Steve Lacy had told me that young musicians would one day come back to melody. This was true for me and for many others.

“I was convinced, fascinated by the experience of the absence of form”

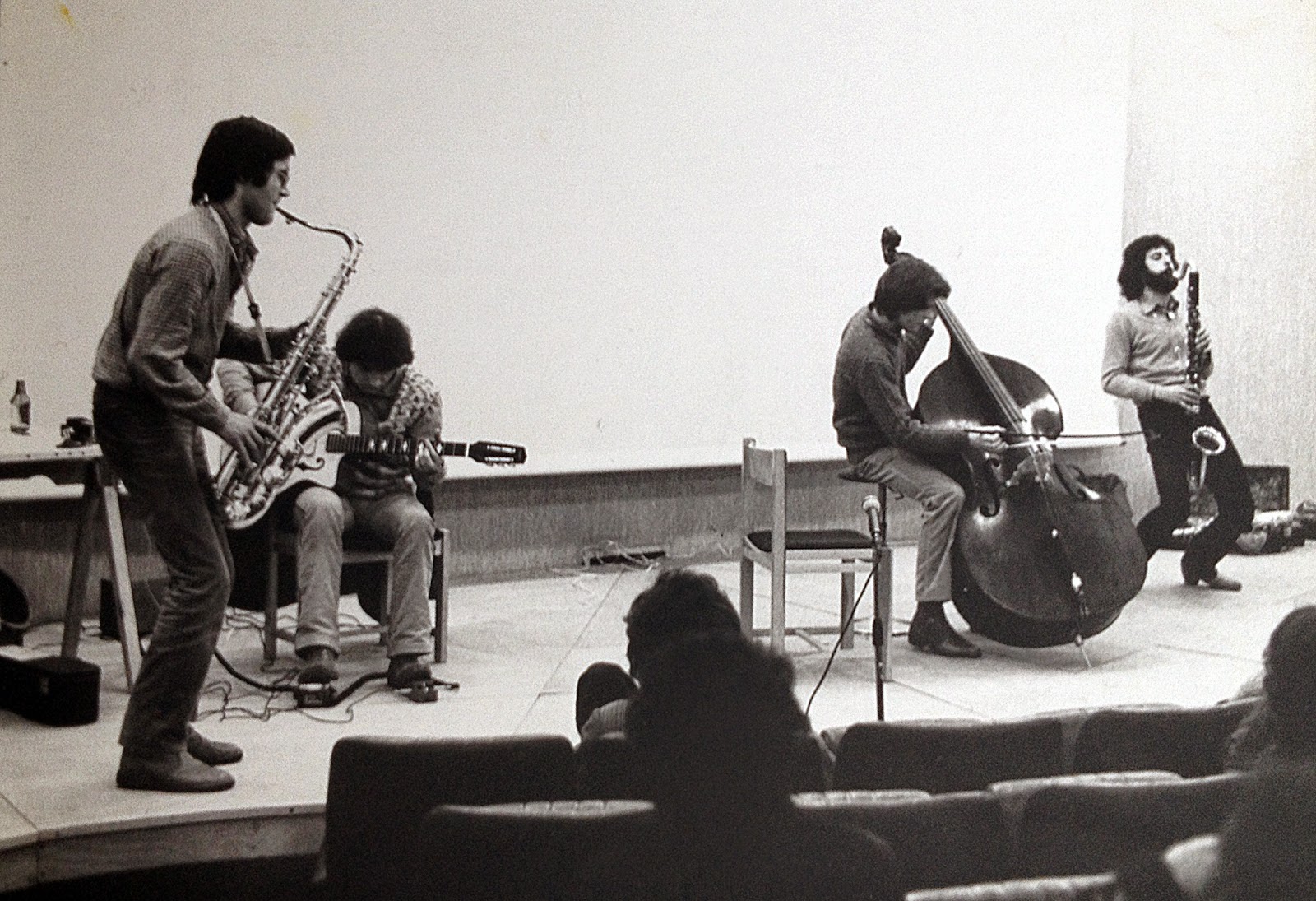

How did you start Axolotl? What was the initial concept behind the group?

There was no concept at all at the start. It was a friendly meeting with Marc Dufourd. We got along well, we agreed on everything. We experimented with different styles of music. The concept came a year later, when Marc showed up with Derek Bailey and Evan Parker’s ‘The London Concert’ album. Marc had said: “We have to play in this direction”. From one day to the next he had started tweaking big intervals of major sevenths and dissonances of minor seconds, noises on the strings, unstructured stuff. It was really good. I was convinced, fascinated by the experience of the absence of form, of the radical listening to sound, of the total adventure towards the unknown. I immediately began to play in the style of Evan Parker, in the “non-idiomatic” style as the sectarians say. Somehow it was the symbol of a search for a possible absolute, a symbolic prelude to a new world. It was not a revolution, but a departure towards infinity. Very quickly, Jacques Oger had joined us and had disciplined the informal and solidified this direction, methodically rejecting any attempt at melodies.

Where did members of the project know each other?

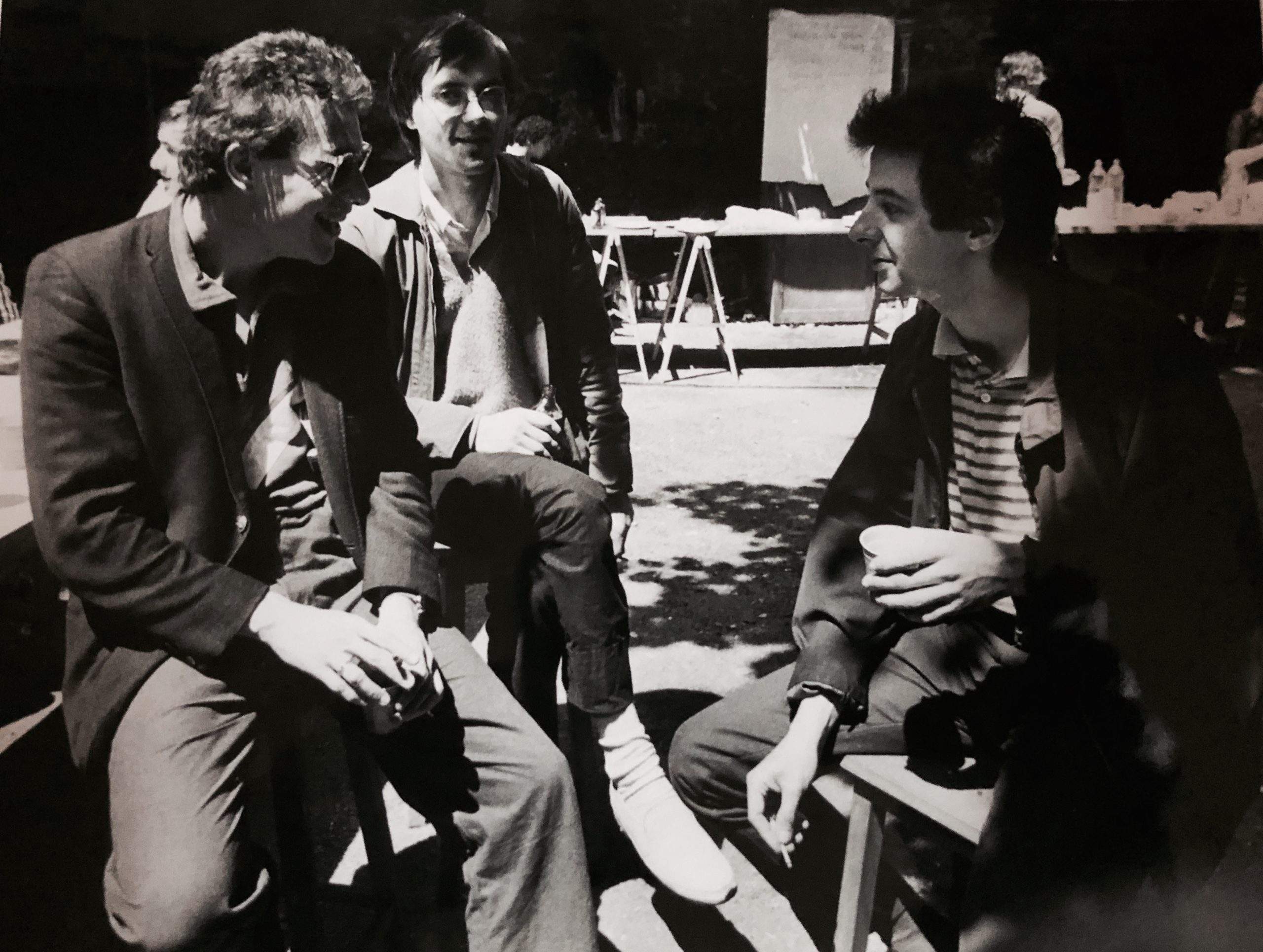

I had met Marc Dufourd through friends and Jacques Oger at Steve Lacy’s workshop at the Chateauvallon Festival, a memorable thing where the spirit of the place was incomparable. The festival was superb, the workshop with Steve Lacy incredibly interesting.

How did you get signed to d’Avantage and what led to recording your debut album in 1981?

Marc Dufourd was very good friends with Jac Berrocal and we had all become a bunch of friends. At the time, the telephone was rare and we always visited each other. We drank hard and laughed like crazy. We were always stuck together. So, quite naturally we made the first album on his label.

Would you like to share some further words about the material on the debut album?

I’m listening right now to the ‘London Concert’ by Derek Bailey and Evan Parker, which I had not listened to for at least thirty years. We were undeniably influenced by this record while bringing a different dimension. It’s not a copy at all. It is a community of spirit. A continuation of sound abstraction towards a new creativity. This first album of Axolotl will soon be reissued by the excellent label SouffleContinu Records (a project of the Paris record store SouffleContinu, near Père Lachaise cemetery). They always do a very fine job. Great.

How did you usually approach music making in Axolotl?

I am always surprised to see for a second time, a few years later, a film that I have loved. I still love it, but I’m rediscovering the story. I had forgotten everything. At the time, we theorized over a drink. Depending on the day, we imagined everything and its opposite. We were often drunk, completely drunk trying to put the world to rights. We changed direction in the middle,under the influence of Berrocal.After the first album, ‘Abrasive'(its front cover was a sheet of sandpaper), we had slipped towards a violent punk rock. We had suddenly evolved from elegant noise at low sound levels to electrification increased in decibels. Vision of industrial chaos. We had gone from “noisy” to noise. A kind of aggressive, excited and violent punk free jazz.

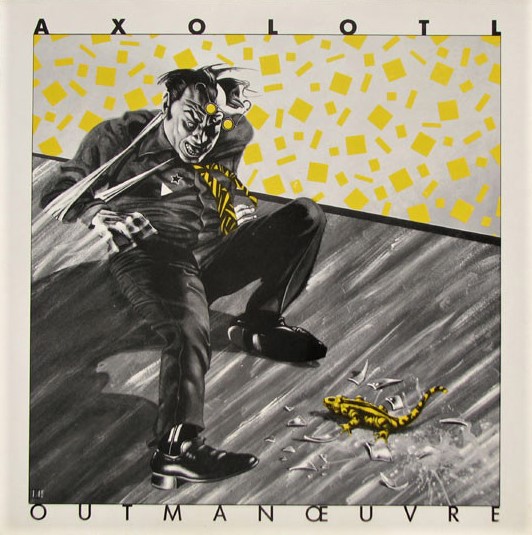

Your second album was released on Cryonic Inc, a label that also released Art Zoyd, Univers Zéro, et cetera. What’s the story behind ‘Out Manœuvre’?

How and why did we end up at Cryonic? I do not remember. Probably to have a better distribution. I have never listened to their music. They ignored us and we paid them back. It is typical of France. We could pass each other for a century without saying hello. On the other hand, I remember that the following year, we had made a video clip. It was directed by Lari Lucien from the group Les Maitres du Monde. They were going to go straight to Canal+, the hard core of short TV programs. It was really extra, but Axolotl had again slipped towards another aesthetic that had nothing to do with either Cryonic or d’Advantage. By dint of mutations of image and sound, the group imploded.

Was there a certain concept behind it or was it a complete improvisation?

We thought we knew what we wanted, but when we found ourselves with a myriad of high-performance condenser microphones, we could hear our blood pulsing and insects flying in the headphones. We were afraid to break the silence. Then Marc turned the amps on full blast and we kicked off the post-conceptual improvisation.

Where did you record it?

We had settled in a huge barn in the countryside in Burgundy near a vineyard. We had drunk the neighbors’ wine more than enough to completely screw up. We had several gear cars with our sound engineer Daniel Deshays.

Did you ever consider yourself as a part of the Rock In Opposition scene?

Absolutely not! I don’t even know what it is!

The album is very complex and the industrial rhythm really gives it a special touch. Please share some further words about it.

It’s a failed album, but carrying an ambition that we did not have the means to achieve. However, the result is more interesting than a successful album in a conventional style. We were mired in the contradictions between punk, free music, contemporary music, jazz, and even French songs. The elements were all incompatible with each other. We thought we could order them. We were at an impasse. We were always in conflict with each other. Never agreed. The big discussions were to oppose setting up and setting in motion. Jacques had produced the first record. I had put in the money to produce this one and was unhappy with the turn of events. Marc almost left the band after recording. He was unhappy for other reasons as well. We had tried with Jacques to save the tapes in the studio and to access my obsessions: the superimpositions of heterogeneous sound elements, the layers of music not synchronized with each other. Attempt to extend non-swinging polyrhythm to “destroy” polyphony long before the so-called poly-free. Two failed takes overlapped gave an interesting trick in the mind of Charles Ives, of course I exaggerate by saying that. Years later, I had continued on this path alone with ‘B/Free/Bifteck,’ but this time each isolated take was super good.

Did you play any shows? If so, where and with what other bands?

Yes, we played everywhere, but we ended up being engulfed by Berrocal, we became part of his group. At other times, we hired two drummers to pulsate the chaos of Axolotl in a new way.

In 1984 you formed Aller Simple Paris, with accordionists. What inspired you to play melodies from Eastern Europe?

Ah, this accordionist: the sublime Gina Sbu! I had met her at a party organized by Jacques. It was the end of Axolotl, but we remained friends until he set up his label Potlatch. Gina was playing alone and I instantly fell in love with her and her music. She played a Balkan, Romanian and Bulgarian folk repertoire. We lived together for several years and I had tinkered with folk, variety, rock fusion arrangements for this group. With Aller Simple Paris we were ten years ahead of fashion. We were unlucky and hadn’t signed with a label straight away. When this music became fashionable, the group had long ceased to exist. Two of the members had settled in the USA. The heart was gone. Life was getting harder. The youth had passed and as I had no career plan, I found myself on the pick-up.

How did your collaboration with the poet Julien Blaine come about?

I had replaced, at the last moment, a violinist who was to perform with Jean-Pierre Bedoyan and Julien Blaine at a festival in Italy. I was amazed and enthusiastic about this current “sound poetry.” Jean-Pierre having settled in the USA, I continued for years to accompany Blaine until his first farewell: “Bye bye la Perf.” He was super powerful on stage. I remember once in Colombia, in Medellín, where he was screaming wildly, completely naked with two hollowed-out chickens on his feet that served as his slippers. Even the underlings of the “narcos” hanging around behind the scenes were scared!

You performed with a really wide variety of musicians, including Jac Berrocal, Anthony Coleman, Wayne Dockery, Jean-Jacques Birgé, Jean-François Pauvros, Guillaume Loizillon, Erik Minkkinen, Jean-Jacques Avenel, Sunny Murray, Yasuaki Shimizu, Emiko Ota, Laurent Saïetm, Cornelius Stroe. Would you like to take a moment and talk about some of the interesting collaborations you had with the above-mentioned musicians?

You forget the brilliant Fred Van Hove with whom I recorded at the church organ in St Germain-des-Près and the whole B/Free/Bifteck team: Camel Zekri, Hubert Dupont, Daunik Lazro, Daniel Mille, Thierry Madiot. I had also often played with the brilliant Jean-Pierre Bedoyan who disappeared somewhere between Los Angeles and New York. No trace of him. Please let me know if you know what happened to him. And also Pierre Bastien. And also Gilbert Pounia, one of Reunion’s greatest musicians. And also the Japanese singer Mai Yaman. And also the African musicians Djeour Cissokho, Mamadou Faye, Ali Boulo Santo and others. And also the great Lisbon improvisers around the Creative Source label of Ernesto Rodriguez, Miguel Mira, Carla Santana, Chico Trindade and a dozen others. Also Berlin improvisers including Tristan Honsinger, Diemo Schwarz. In other circumstances, Benoit Delbecq, Steve Argüelles and Christophe Mink.

The formidable musicians of Bangkok: Pengboon Don, Chainad Bavorntreerapak and Pok. And of course, Thierry Negro and Eric Borelva who participated in all my groups for two decades. I may have misunderstood the question, should I have mentioned the ones mentioned above? Cornelius Stroë: yes! It was a wonderful adventure and I was very sad to learn of his death. He was a ball of energy as well as a very subtle drummer and musician. “Post Communism Atmosphere” which I recorded with him is my favorite record. I can also say a word about Anthony Coleman. I had met him at the Acanthe center in Aix-en-Provence for Mauricio Kagel’s composition lessons. We immediately hit it off. Then he had lived for a few weeks in Paris with me. We had a rather failed concert. Then he left for Yugoslavia. This was before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the country had not yet split into several republics. Then he returned to New York where he played with John Zorn. So obviously I no longer interested him … Ah ah, especially since I had few concerts to offer. But I always regretted not having set up an orchestra with him.

How did the Zig Rag Orchestra come about?

I had already played several times with Corneliu in Romania just after the fall of the Berlin Wall. I often went there at this time. The atmosphere was extraordinary. Hopes for the future which once again were quickly disappointed … In one or two years, the country had sunk into the most savage capitalism. I had imagined and produced this ambitious musical project. I had recorded a 16-track tape at the standard of the only private studio in Bucharest at the time. I had put down the samplers and the synths so as not to transport heavy machines on the plane. That was over thirty years ago and we didn’t have the mobility of a studio in a laptop. We had gone to Bucharest with the guitarist Laurent Saiet. The recording was not easy because Corneliu found himself forced by the click of the metronome to synchronize the machines and he began to howl madly, accustomed to giving his own wild tempo. But finally his creative fury gave an energy worthy of the greatest drummers. It was a super awesome experience. Then once the record was out, we had to put together a new version of the band to play in France. I couldn’t afford to invite Corneliu. I had met Erick Borelva, who is also a wonderful, subtle and energetic drummer. Then I had signed one of the last old-fashioned contracts with the Saravah label, a contract for three discs and we made a new CD “La Légende du Franc Rock’N’Roll” with other additional musicians, always under the name of Zig Rag Orchestra. I had Benjamin Ritter who provided the voice with a very new wave timbre. The group had completely changed color again. Moreover, the director of the Saravah label, Pierre Barouh, was very disappointed. I thought I would please him by writing a crazy French song album while he wanted the continuation of the Romanian folk jazz style of my previous album. But he let us. He discovered the record while mastering.

Then there’s 3D Jazz…

It was the same project as Zig Rag, but with a different name. It’s one of the many mistakes I made to change my name. We had done concerts with video projections of works by Marie-José Pillet.

And then the orchestra was of variable geometry according to the availability of the musicians. In duet with the formidable Wayne Dockery or with my usual musicians.

What about Ring Sax Modulator?

It was the end and the conclusion of this adventure of the two previous groups. A different name, but the same aesthetic approach and still the same formidable rhythm section: Thierry Negro and Erick Borelva. I played sax and synthesizers. The disc was released this time under license by Saravah in addition to my 3-disc contract. The disc crisis was general. Benjamin Barouh, who took care of me as label manager, was fired. It was the beginning of the end. France’s first and oldest independent label had become dead alive. I thought he had gone bankrupt, but he just didn’t do anything except manage the rights of their first artists who became famous in France. They didn’t take care of anything and the album went unnoticed. The music was great, but again I was unlucky. Commercially I have always been useless. We didn’t have any success, but we had a good time and somehow we paved the way for the next generation, this kind of post jazz mixed with lots of influences of a rhythmic and festive nature that works so strongly in France.

Tell us about your love for Louis Jordan?

My argument is controversial, but for me he invented rock and roll long before electric guitarists. Saxophonist and singer, he was an ideal model, but in the end I went in another direction and asked Benjamin Ritter to sing in my place. I couldn’t. I was very interested in the evolution that Louis Jordan imposed on the twelve bars of the blues to transform them into rock and roll, to mutate from sadness to joy.

What else did I miss?

Well, you haven’t forgotten anything, but there are so many things I didn’t say… You can find all my records (except Axolotl’s Outmanoeuvre which I didn’t have the courage to digitize) on Bandcamp accessible free of charge and extensive documentation on my website.

What else currently occupies your life?

I write a lot, but I don’t have a publisher. I’ve been looking for one for ten years. I am economically retired so I spend half my time in Thailand. I’m tired of Paris and its piss-vinegar inhabitants. I no longer expect anything from France as an artist. In Bangkok, musicians are not sectarian. All styles mixed, amateurs and professionals, they have been organizing something fantastic since Covid 19: concerts on Sundays at the end of the afternoon in the streets of the sprawling city.

They install a sound system under highway interchanges, on vacant lots, on the edge of railway tracks. They gather their friends through social networks. Their thing is called: “Bangkok Noise and Roll – Street Gig”. It’s a really great place, frequented mostly by young people.

What are some future plans for you?

Projects? I haven’t had any since the start of the war in Ukraine. I expect to hear every morning that a missile has just exploded at a nuclear power plant. Or when the sun of inflation has melted my pension. Or that a new pandemic will kill us. Culture no longer has any meaning. We quietly watch people being killed in the media. The world has become a “snuff movie”. Well before the war, I had started electronic music for a monumental sculpture by Fred Sapey-Triomphe for the “Fête des Lumières” in Lyon. Despite everything I continue to study the music of the past without trying to create stuff that will not interest anyone. From time to time I look for a publisher for my typescripts and my “Web Web Opérette”, but the dice are loaded without networks of friendship and reciprocity in the cultural belly of a ministry turned towards the absence of creativity. I am old, and no one is interested in my activities anymore. I have no support. So too bad.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

I’m going to be long and yet I forget half of it. I’m crazy. I change my musical opinion every ten years. Coming out of adolescence I was crazy about John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Daunik Lazro, Sun Ra, Gato Barbieri, Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, Velvet Underground, Captain Beefheart, Janis Joplin, Léo Ferré, Terry Riley, BB King, Muddy Waters, Louis Jordan, Billie Holiday, T-Bone Walker.

Then at the end of the ’70s, it was always John Coltrane. I fell in love with Steve Lacy, Peter Brotzmann, Evan Parker, Derek Bailey, Globe Unity Orchestra, Anthony Braxton, Michel Portal, the No Wave of New York with particularly James White, furious heir to Louis Jordan, Kraftwerk, Nina Hagen, Chrissie Hynde, Alain Bashung, Pierre Barouh, Serge Gainsbourg, the mini operas of Robert Asley, the rock poems of John Giorno, Kurt Weill, Mauricio Kagel, Stockhausen, John Cage, Claude Debussy and Olivier Messiaen. And also Washington’s Gogo Music. And also Romanian musicians Marcel Budala, Romica Puceanu, Maria Tanase, classical musicians from North India like Hari Prassad Chaurassia, Vilayat Khan, Ravi Shankar…

The decade after: still John Coltrane, but I was crazy about Funkadelic, James Brown, Curtis Mayfield, Tower of Power. African musicians: Fela, Youssou N’Dour, Ali Farka Touré, Salif Keita, Orchestra Baobab. One year I listened to Toumani Diabaté almost on repeat. To the opposite and contradictory aesthetics I was fond of the school of Vienna: Schoenberg, Webern and Berg. I had fits of tears listening to Dmitri Shostakovich. I was more and more torn between mutually incompatible music. I was hooked by the style of Paul Desmond and Stan Getz, by the compositions of Tom Jobim…

In recent years I have been pushing both reverse and forward gear: I am treading water at full speed. I listen to and study the classical repertoire: Malher, Bach, Bizet, Wagner, Gounod, Puccini, Beethoven, Mozart, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, authors of jazz standards, composers of film music, etc. I am very interested in Frank Zappa’s opera, ‘200 Motels,’ and also in Morton Feldman and especially in the graphic scores of Cornelius Cardew. I transposed his approach into a video: “Novo Video Scratch”. I project on stage a kind of graphic composition halfway between VJing and video art and we improvise the reading of pseudo-contemporary instructions.

Thank you for taking the time. Last word is yours.

I stopped producing records more than ten years ago. I participate in recordings when it is offered to me, but I no longer make personal records. No one buys CDs anymore. I had started making music videos posted on the Internet to compensate for the lack of a record. At first it seemed like a good idea, but now it doesn’t make sense, drowned out by millions of YouTube channels. I’ve been doing websites since 1998. It was fun stuff with no big impact. Now the web has completely replaced the real world. Last year, I had set foot in “web 3.0,” the blockchain. I had tinkered with NFT (New Fuck Token) to ask for support as an artist, to help me make new projects and to reward me for 50 years of creativity. I haven’t sold anything. Marginal in the real world. Unknown in the virtual world. I had called my marketplace page: “unsold_museum” on the specialized site Opensea. I made a false manipulation and I lost everything! Something happened to me that never happens on the blockchain since nothing can be erased. Platform bug for me. Extreme loneliness in front of the computer. The current technological evolution will be worse than the mutation of the CD into mp3 files or streaming. Cryptocurrencies for everyone and monkey money for creative musicians. Facebook “likes” will be replaced by a virtual currency like in a video game: you will give a few cents to artists like you give a coin to street musicians who are begging. The royalties will be paid in “like” convertible in dollars only if you make more than 10,000 “hits”. Below, the likes will be paid to the robot [“GAFAM” shut up]. No need for musical knowledge. It only takes a marketing degree to express yourself. So many useless tears. For the purchase of a pair of sneakers, you win an NFT of thirty seconds of music. Robot shop! In one click you disappear. My last word: help!

Klemen Breznikar

A special thanks to Jason Weiss

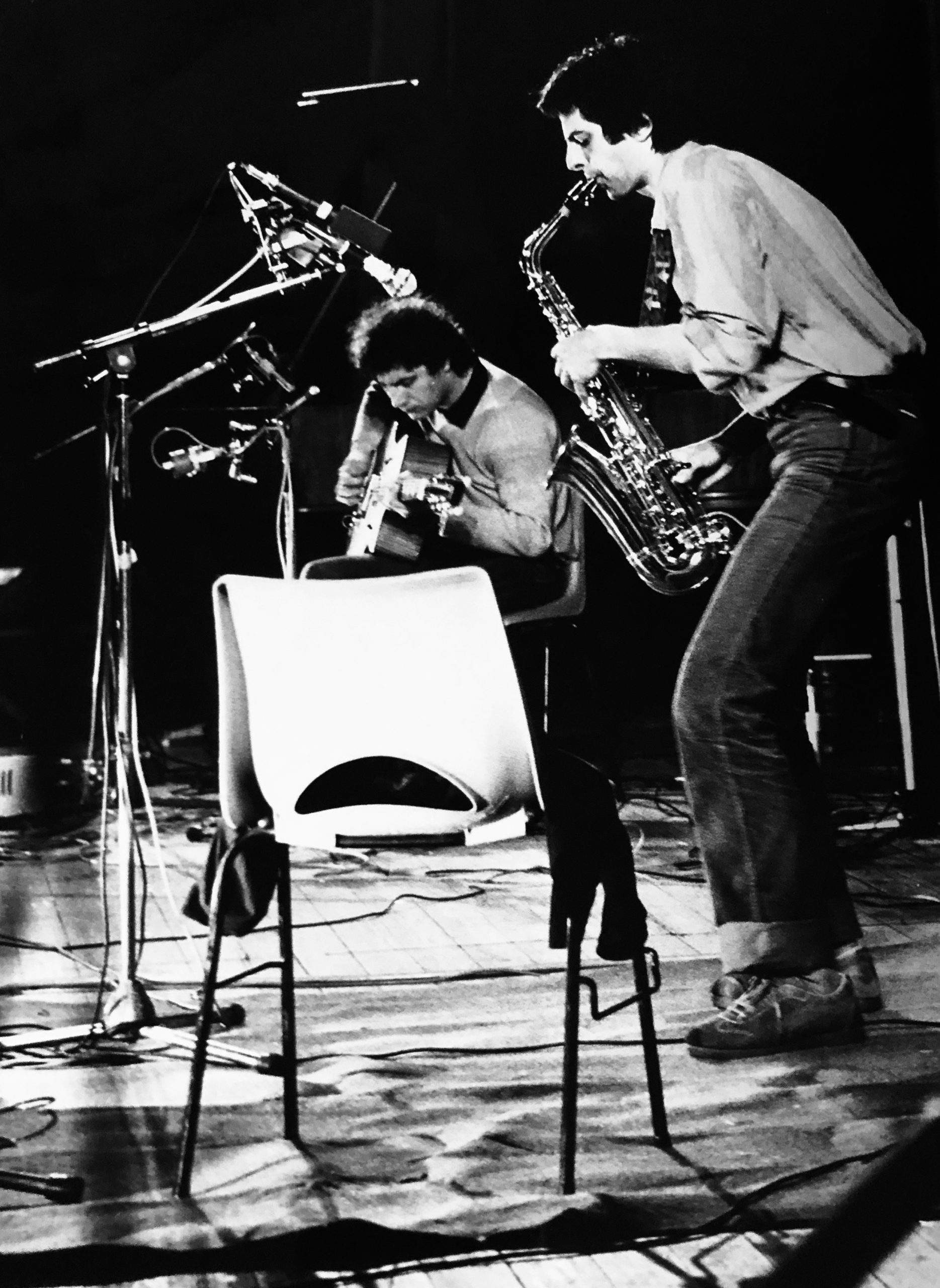

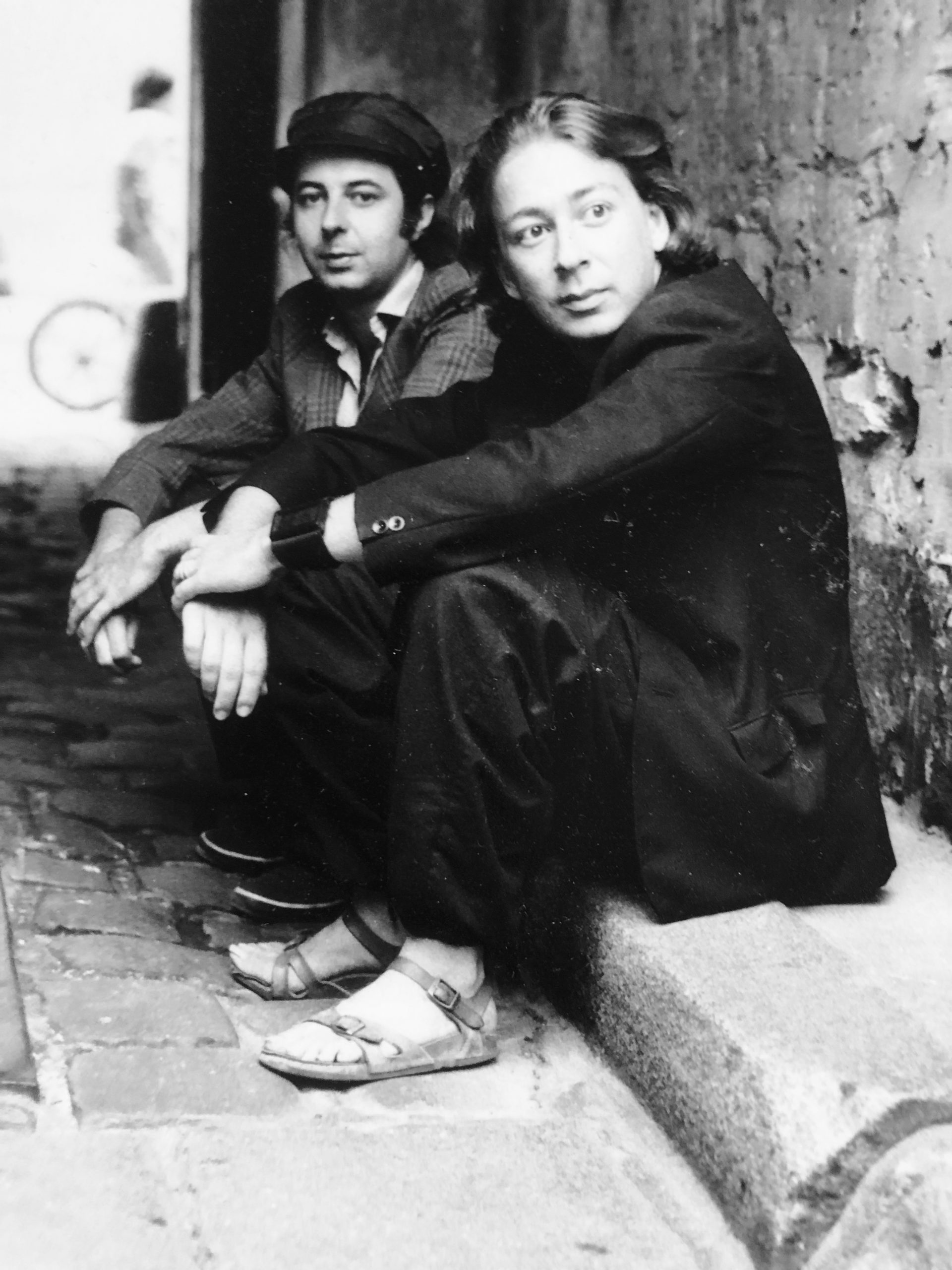

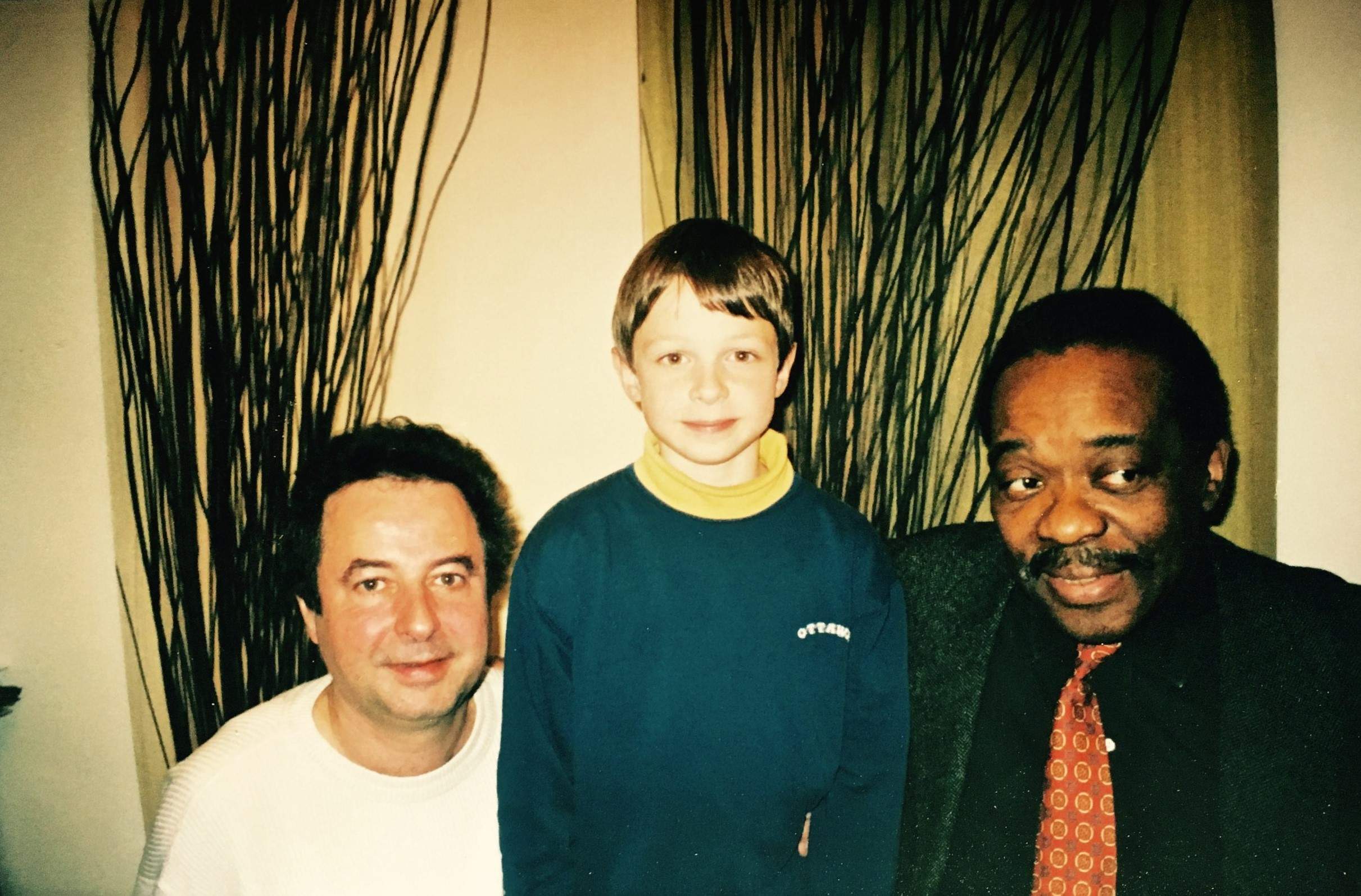

Headline photo: Axolotl in 1982

Etienne Brunet Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube

SouffleContinu Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

One of the most entertaining interviews in the site. Brunet is very much of his nation – compellingly intellectual. It’s good to know Axolotl’s recordings are going to be reissued – “Out Manoeuvre” is one of the finest experimental recordings made.