Dorothy Moskowitz & The United States of Alchemy | Interview | New Album, ‘Under an Endless Sky’

‘Under An Endless Sky’ represents the interchange that took place between electronic composer Francesco Paolo Paladino, composer and writer Luca Chino Ferrari, and the legendary Dorothy Moskowitz, an icon of underground culture who broke all kinds of new ground as a member of The United States of America.

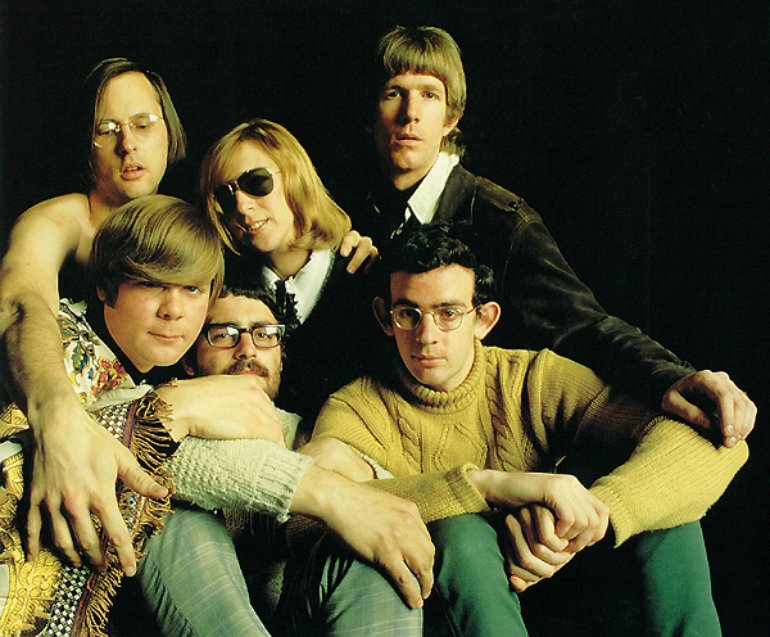

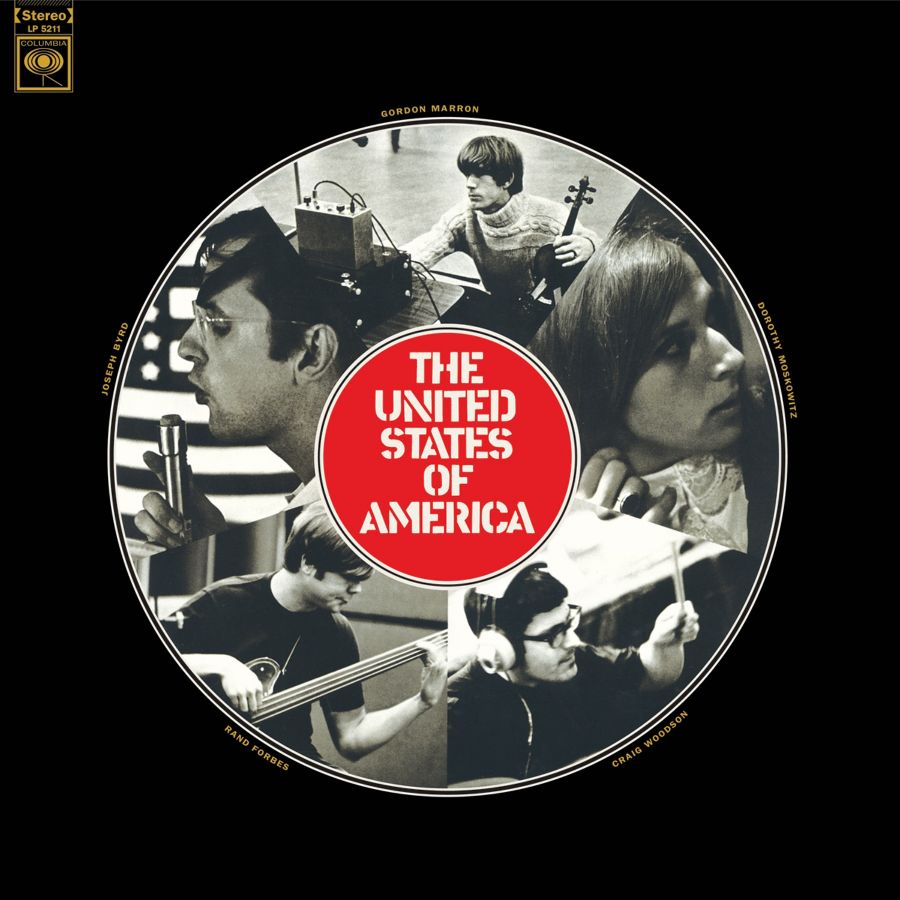

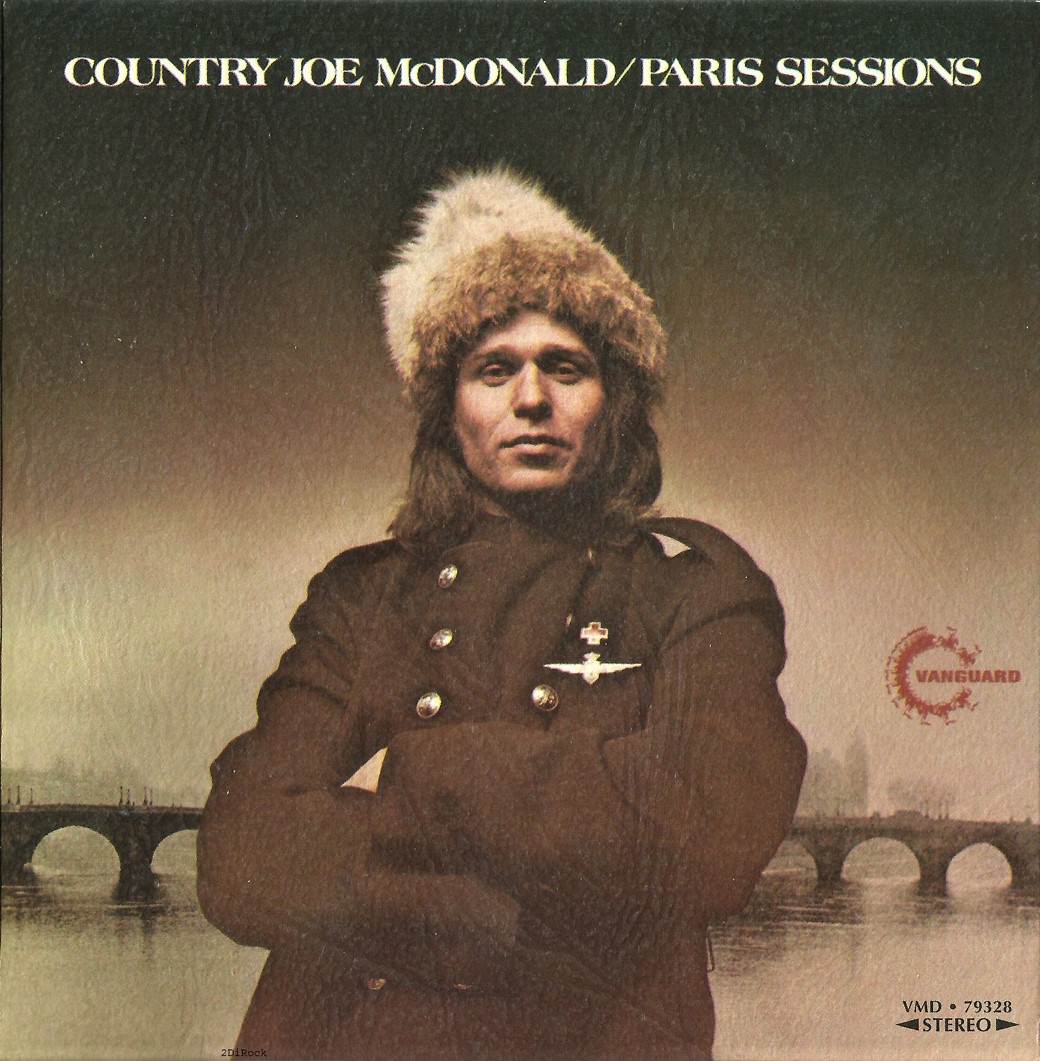

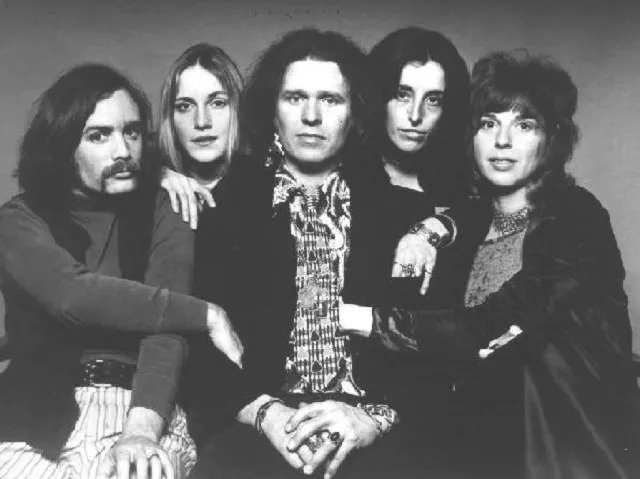

The United States of America was an experimental rock band founded by Joseph Byrd and Dorothy Moskowitz in Los Angeles in 1967. Along with violinist Gordon Marron, bassist Rand Forbes, and drummer Craig Woodson produced one self-titled album. The 1968 self-titled album received critical acclaim and is often cited as a forerunner in psychedelic rock – being the first band to use synthesizers and modulators. They disbanded shortly after its release. After the United States of America, Dorothy Moskowitz toured and recorded with Country Joe McDonald as a member of his All Star Band. They recorded an album in Herouville, France, where Dorothy enjoyed playing on the same grand piano Elton John used in ‘Honky Chateau’.

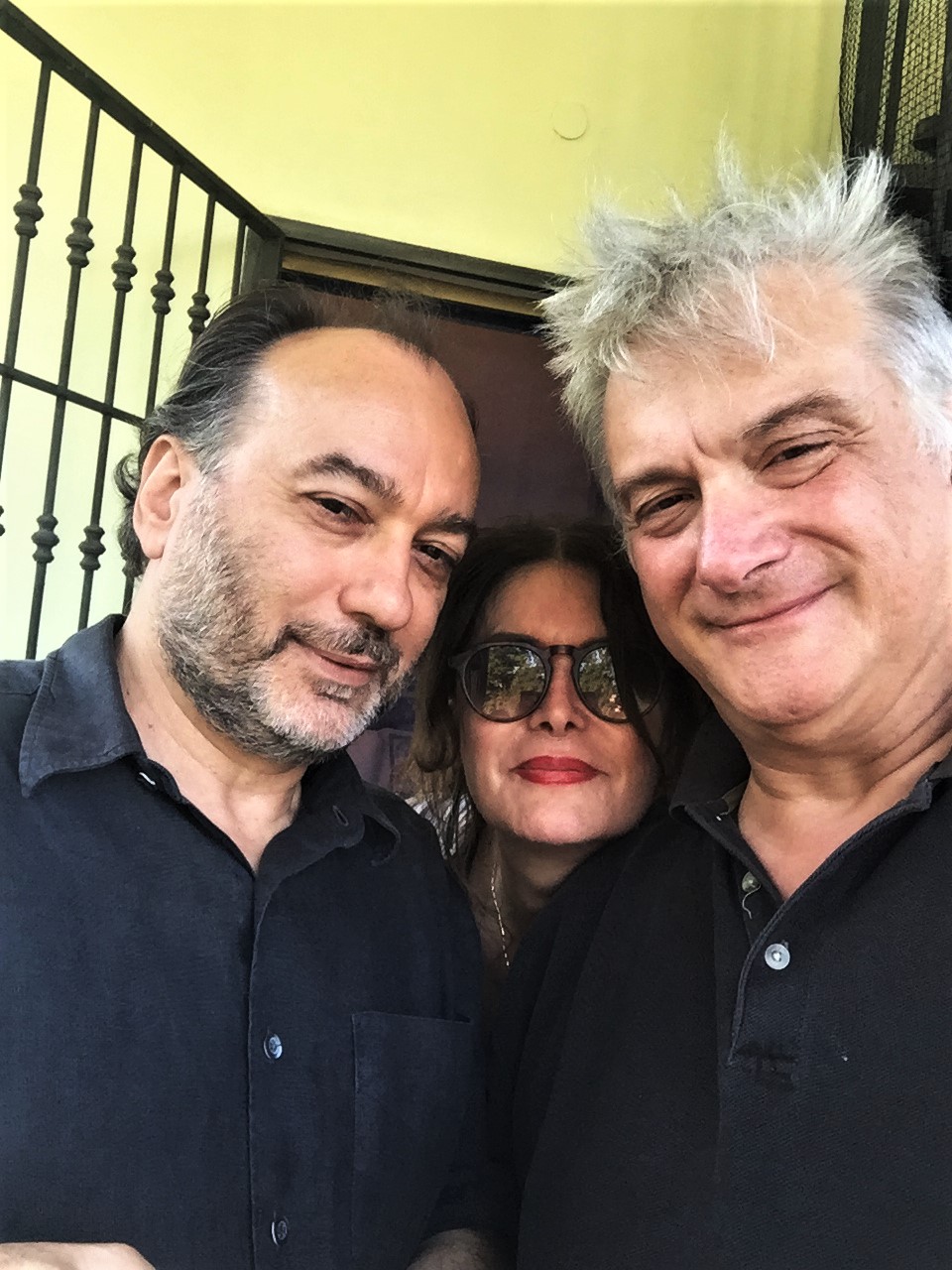

Francesco Paolo Paladino, an avant-garde Italian composer contacted Dorothy Moskowitz, inviting her to sing on some of his compositions. When she heard his 2021 CD release of ‘Barene & Other Works,’ she recognized that they shared a similarly experimental point of view and she accepted his invitation. Francesco has long collaborated with Italian writer Luca Chino Ferrari, author of biographies of Nick Drake, Third Ear Band, Captain Beefheart, Tim Buckley and Syd Barrett. He submitted lyrics to Dorothy and together they began a profound and unique collaboration on the adaptation of lyrics to music, delving into words and meanings, phonetic properties and their singability. “Lyrics that have the audacity to deal with complex themes of human existence, real philosophical cutaways that look at reality and question it, often without offering answers,” says Ferrari. Moskowitz’s extraordinary voice and modal melodies float over Paladino’s magical musical textures. There are no guitars, bass, drums or other technological devilry, but only virtual sounds (sometimes without even keyboards) upon which are grafted some acoustic interventions: violins and violas, woodwinds and percussion entrusted to excellent musicians such as Italians Riccardo Sinigaglia, Angelo Contini, Stefano Scala, Trio Cavallazzi and Gino Ape, and English folker Sean Breadin.

“We were highly experimental in attitude”

It’s fantastic to have you. How did you spend the last three turbulent years? As an artist, have you found the isolation creatively challenging or freeing?

Dorothy Falarski [Moskowitz]: Thanks, Klemen. I probably wouldn’t be the subject of this interview had it not been for COVID. Unable to jam with friends or play viola in an orchestra, I upgraded my tech skills. I learned to compose with digital tools and I freed myself from the anxiety of needing an expensive recording studio to be heard.

I’m extremely excited about your upcoming album, ‘Under An Endless Sky’. Would you like to discuss how you originally got in touch with electronic composer Francesco Paolo Paladino and composer and writer Luca Chino Ferrari?

I’m excited as well. My connection with the two came about from my collaboration with the novelist/critic Tim Lucas. He patiently supported my digital learning curve while we worked on music for his remarkable novella The Secret Life of Love Songs. The music caught Francesco’s attention and he contacted Tim, proposing collaboration. Tim had a busy writing schedule, but I was free and curious. Curiosity turned to commitment once Francesco presented me with his recent Barene & Other Works, a quasi-mystical tribute to the Venetian salt marshes. It was beautifully peculiar. I was hooked.

Francesco introduced me to music writer Luca Chino Ferrari, his friend and long-standing collaborator. Luca described his background as “writing about underground artists since the mid 80’s…especially when no one in Italy cared about them.” He considered it his “personal tribute to art seen from its Dionysian propensity.” I was hooked once more.

What led to the ‘Under An Endless Sky’? Would you also like to share how you approached music making?

Francesco initially asked me to sing selected passages on his lengthy opening suite ‘Under an Endless Sky’ plus a few more songs still in progress. Luca sent poetry with imagery and emotionalism unlike anything I’d sung before. His English translation needed smoothing out, but he gave me complete freedom with cadence and English vernacular. He responded generously to my changes and offered half lyric credit. I’m still not sure I deserve so much, since he originated the premise for each piece.

I’d compose a vocal melody with revised lyrics and send it to Luca, to assure I had conveyed his intention. We would delve into meanings and subtleties of language, developing deep trust and friendship along the way.

Our draft went back to Francesco for comment. He’d respond with notes like: “Have it float, like on the USA!” or “Leave it dripping with emotion!!!” I include the extra exclamation marks here to convey Francesco’s continuing blaze of contagious energy. Luca and I would send versions back to him for mixing and he would often surprises us with daring splashes of Musique Concrète and neo-Dadaism

I think it’s fair to say that the coupling of Francesco’s turbidity with my restrained interpretation of Luca’s distinctive poetry echoes the formula that made the USA so unique and memorable.

Where was the album recorded?

All the vocals were recorded in my home studio here in California. The rest of it was done in Italy.

Your voice in combination with Paladino’s textures gives this a very experimental edge to it. Did you start the project with a certain concept or was the album a result of improvisation and experimentation?

I heard the experimental quality in Francesco’s music before we even started working together, as I indicated.

You also had many other musicians being part of the record, including Riccardo Sinigaglia, Angelo Contini, Stefano Scala, Trio Cavallazzi, Gino Ape, and Sean Breadin. Are you happy how the album turned out?

I’m very happy with it and give kudos to the many instrumentalists, who provided the sonic paint box for Francesco. It’s amazing how we all coalesced without ever meeting. For instance, at the end of ‘Doomsday Serenade,’ I sing a slow ballad over the Trio Cavallazzi. I’d intended that melody for another passage, but Francesco heard how my harmonies matched his string excerpt and layered it in. It fits like a glove.

Another surprise connection was made in ‘My Last Tear’. Luca’s lyric refers to “black cows in the black night,” a Hegelian gloss suggesting a sense of useless abandonment. He and I discussed the idea without Francesco’s being involved. The instrumental featured Angelo Contini on trombone. When it all came together, those languid trombone lines implied, at least to my ears, some very dark cows.

Would you mind if we go back and discuss your early days? Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

I grew up in Yonkers, New York in the 40’s and 50’s. My older sister was a fine pianist, so I was exposed to classical music very early. My mother had an attractive singing voice and she said her father did as well. There were cantorial singers on her family’s side, one cousin a composer. My father seemed tone deaf, but sang (and danced) uninhibitedly. His touch of exhibitionism might well be something I inherited.

“Whenever there’s a need to expose my insides in a song, I think of Chet Baker”

What kind of records did you like to listen to? What kind of literature were you interested in? I’m guessing it would be Beat literature at the beginning of the 60s.

We had sheet music ranging from Chopin to Pinetop Smith on our piano bench and piles more overflowing on the piano stand. Bach. Billy Taylor. Beethoven. Hazel Scott. Our record collection was also eclectic. At around eleven, I would leap about my living room to Debussy’s ‘Fetes’. At seventeen, I’d be excited by Tito Puente, only without all the leaping.

I was no different from anyone else my age when it came to rock and roll, except that I favored Gene Vincent over Elvis Presley. Everyone liked Chuck Berry and Little Richard, but we worshiped Fats Domino. We’d hear him from a passing car radio during class and stand up with our hands on our hearts.

I also liked modern jazz and followed Charlie Parker, Stan Getz, Lennie Tristano and singers like Chris Connor. I still own my treasured copy of Chet Baker’s first vocal album. Whenever there’s a need to expose my insides in a song, I think of Chet.

I was influenced by Beat culture long before I actually read Jack Kerouac or Gary Snyder or Alan Ginsburg. I had more conventional tastes at first and remember liking Thornton Wilder in high school and the Modern and Victorian poets in college.

How did you first start playing piano?

I played before I could read music, improvising tunes on the black keys and playing chopsticks. Lessons began at ten and continued until fourteen. My first paid gig was in high school, as accompanist in a dance studio run by a retired Ziegfeld Girl. Her recitals were elaborately vaudevillian with a professional customer, plus bass and drums added to my piano for a vintage combo effect. After college, I resumed formal lessons with jazz pianist John Mehegan. I still have his book and it still mystifies me.

You attended Barnard College, would you like to talk about your college years and how did you learn vocal techniques and composition?

I think I had pretty solid vocal techniques and tune-writing skills before I graduated in high school. Music education wasn’t considered a frill back then. Collegiate literature classes influenced my lyric writing and the informal extra curricular activities helped with my musical development.

The major American poet Robert Pack was my freshman English teacher. His specialty was Wallace Stephens and he taught deep reading of complex writers like Yeats and T. S. Elliot. I took other literature classes, though I wasn’t an English major. I never expected Robert Browning’s skills in character writing to remain so important to me or that some of Tennyson’s or Swinburne’s musical lines would stick in my brain like earworms.

Outside of classes, I got to write music for two original musicals, direct the a cappella group, compose a winning ballet score and co-write the Barnard alma mater. I also sang jazz in the local student center and did a little acting. In my senior year, I portrayed Adelaide in the Columbia Player’s production of Guys and Dolls. It was directed by David Rubinson, who later became the producer of the USA.

How did you get training from Otto Luening?

Professor Leuning instilled audacity. He taught me to trust my ear. I met him when he was on staff at Columbia when I attended a workshop that he offered Barnard students who were interested in scoring music for the traditional “Greek Games” competition. People kept dropping out and I wound up having private lessons. My piece won that year and the points I earned led the class to victory. I was lofted on the shoulders of my classmates with a laurel wreath on my head. The following year I was Leuning’s usher for the new games and we spent a long and cordial day together. I’ll always remember him as very down to earth, witty and loveable.

What was the scene like back then for a person with your interests?

Until you asked this question, I never considered how the transition from a gawking suburban teenager to a string player in a La Monte Young concert came about. On my own, I would never have sought out a scene as such. I didn’t think I needed one. I was lucky enough to grow up in a place that was close enough to Manhattan that off-Broadway, legit theater, jazz clubs and museums were within reach.

I became part of Joseph Byrd’s scene after we met. He was a respected Fluxus-inspired composer then and his circle of avant-garde friends was wide and diverse. He introduced me to almost all of them. I’ll name some here, to give you a sense of the artistic ferment: Charlotte Moorman, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Max Neuhaus, Eric Hawkins and Lucia Dlugoszewski. I also experienced “happenings,” then a very new art form inspired by the Rutgers professor Alan Kaprow. I became friends with several of his students.

In the Spring of 1963 you went to New York and met Joseph Byrd. Would you like to discuss how that came about?

Coincidence. The lutenist Julian Bream was at Carnegie Hall and I had a free ticket because I worked for his producer at RCA Victor. By chance, I found myself seated next to a school chum, who had come to the event with Joseph. We sparked somehow and soon he encouraged me to leave RCA Victor to join him at Capitol Records. I assisted him with a “Time-Life History” album. We also collaborated on a “Christmas” album.

I would love it if you would discuss the series narrating the history of the United States.

It was a twelve record collection called ‘Sounds of History’ tracing American History from the Mid 18th century to the end of WWII in music and spoken word. The noted composer Virgil Thomson was the nominal music director, but Joseph Byrd had free rein as Thomson’s former secretary. One side had narrations by Florence Eldridge and Frederic March. The other side had music of the period, showcasing such outstanding musicians as Jean Richie and David Weissberg. It recently surfaced on eBay.

How did your move to California / UCLA come about?

Joseph Byrd was accepted to a PhD program in Ethnomusicology. I had no particular plans other than romantic adventure, so off we went together.

I would love it if you could elaborate on the “Feminism and I” class you had, what were some of the main themes?

It was actually called “Feminism I” and I taught it at The New Left School, which Joseph and I founded in 1965 with a hope of fostering a unified platform for what was an increasingly splintered and potentially impotent left. My intent was to have students bring in clips of ads from print media and evaluate them for insensitivity to women. My students were not all that interested in such an exercise. Instead, they wanted to discuss things like unequal salaries, glass ceiling and disrespectful treatment of women.

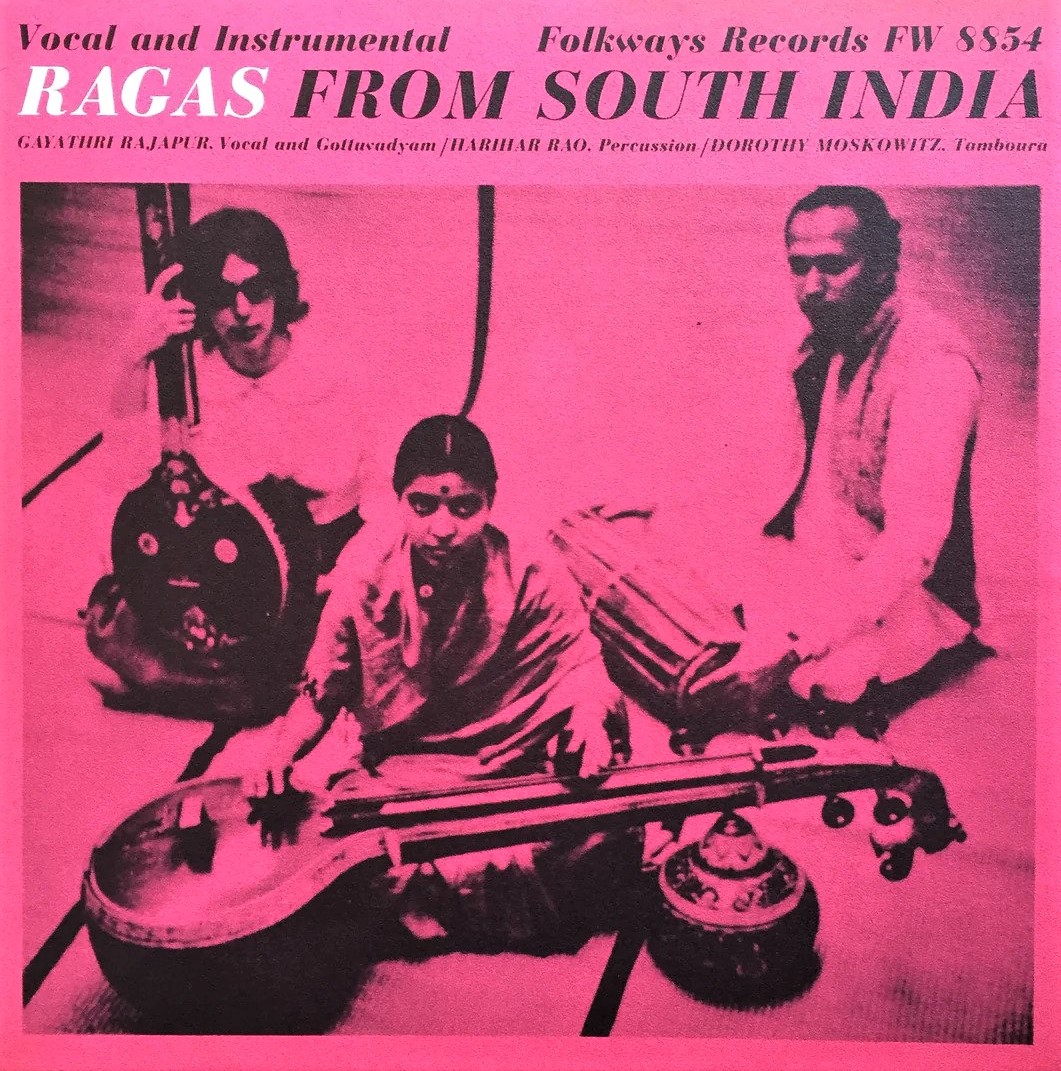

Tell us about Gayathri Rajapur and Harihar Rao collaboration.

Joseph Byrd was interested in South Indian music at UCLA. I was enrolled in another department, but frequently sat in on classes. Gayathri was a lecturer and also our housemate. Harihar had been Ravi Shankar’s assistant. Joseph arranged for a recording and got it to Folkways. I appear on the cover of tamboura, a drone instrument requiring little skill, which is usually played by a favorite student.

Around 1966 you decided to move back to New York. What did you do there for several months until Byrd asked you to join The United States of America? Did you have to think about it?

I worked as a copy editor, first for pollster Lou Harris and later at Time-Life Books. I was comfortably settled in Brooklyn Heights, but I wasn’t doing anything artistic. It was a way back to what I’d loved.

How would you describe the creative chemistry between Joseph Byrd and Michael Agnello? Was it difficult to connect and sync with their ideas when you started this project together?

Joseph Byrd and Michael Agnello started the project and I was invited in because the three of us had collaborated on experimental concerts and happenings before I left LA. At the time, I believed that Joseph and Michael shared a similar point of view and was surprised at Michael’s dissatisfaction. I understand it now.

Following a single live performance, the band was signed to the major Columbia. Would you like to talk about that gig?

It was at the Ash Grove in LA. The band was much louder than it had been in rehearsals. Some people told me my voice was buried. I believe it. Michael Agnello was a master of provocation and lent a spontaneous edginess which pleased our producer David Rubinson. He was also dismayed that Agnello left.

What are some of the strongest memories from producing and releasing your LP? After all, it was a very complex task for the band and producer, David Rubinson.

I overdubbed my vocals separately, while band members worked in group sessions. There was a host of LA’s finest studio musicians involved, with nearly all their scores written and arranged by Joseph Byrd. No pre-recorded music was used. The album was recorded on eight-track, with extensive “ping-ponging” to accommodate so many elements. The main recordings were done in LA’s Columbia Studios. Final mixing and additional electronics were added by Byrd and Rubinson in New York. Given the structural limitations, getting such a rich sounding stereo product is nothing short of inspiring. Where’s the engineer’s Grammy?

You sang through a ring modulator and electric filtering … how did you get ideas like that?

Joseph Byrd and I asked our friend Tom Oberheim, whom we knew at UCLA, for a ring modulator, initially intended for instrumentals. I asked Tom to fashion one for vocals. I experimented on it and was smitten. We wound up using a Durrett synthesizer on the album, as I recall.

The ending result was one of the most psychedelic records ever, in my opinion. I’m guessing that was not an intention?

We were highly experimental in attitude. We were called “psychedelic” by the publishing and marketing world and somehow the descriptor stuck. If it in any way led to your lavish praise, I’m perfectly fine with being labeled “psychedelic.”

“I’m actually considering, as of this writing, a theme-based album that explores interactions and experiences of the USA”

Would you discuss what exactly happened that you decided to stop?

It’s fair to say that the misunderstandings that lead to the breakup might have had less impact had Michael Agnello remained in the band. Our producer became less interested in us and it led to Joseph Byrd wanting to replace him. The reasons for my disagreement with that notion remain personal and intricate.

I’m actually considering, as of this writing, a theme-based album that explores interactions and experiences of the USA. It’s still very much on the back burner.

Did you ever experiment with psychedelics back then? Did it have any influences on you as an artist?

No gigs or performances were done under the influence, although I myself had a few trips prior to the band’s forming. There’s one daft exception. I dropped acid late one afternoon, not knowing that Joseph Byrd had scheduled a commercial session for the following day.

I still recall the jingle he wrote: “Jack in the Box, drive through restaurant, Jack in the Box,” which I sang with mild enthusiasm. Our producer, “Man in the Street” comic Mal Sharpe had no clue and smiled through it all.

How did you get involved with Country Joe McDonald and the All Star Band?

Country Joe McDonald and I first met at a party after one of the USA’s Ash Grove gigs. Country Joe claims no memory of it, possibly because he was under the spell of Nico, partying in LA at the time. Producer/composer Ed Bogas was finally instrumental in connecting for real a few years later. Bogas had written some of the USA’s material and joined us on stage.

You did quite a lot of touring with them, including Europe twice… What was the experience like for you?

It was a combination of high adventure and low comedy. Or maybe vice versa; I can’t remember now. The escapades are worth another long interview. I hope we have one someday.

Tell us about the “Paris Sessions”.

Most of the album was recorded at the Château d’Hérouville in France. For me, it was a delightful and glamorous time. Sure, the dining tables were covered in vinyl and the walls of my cave-like room suffered lingering dampness.

But we weren’t very far from Paris, near Auvers, where Van Gogh spent his final days, and within a day’s drive of Chartres. We had all our meals prepared by staff, we had access to a fine recording studio and best of all, I got to play on the same piano Elton John used on ‘Honky Château’. When you ask about my proudest performance, I think it was the sound I got for McDonald’s ‘Fantasy,’ on that album. A good instrument can certainly elevate your musicianship.

We shared lodgings with Jethro Tull and it seemed to me that Ian Anderson didn’t share my joys with the venue. I never got to meet him, since he left shortly after our arrival. I did become friendly with keyboardist John Evan.

According to Discogs you also collaborated with a UK group called Locomotive?

I never worked with them, and I’ve only recently heard of them.

Were you a fan of ‘Electric Music for the Mind and Body’?

Absolutely. It was a startlingly innovative release when it came out in ’67. I’m pretty sure that Joseph Byrd was inspired to write ‘Hard Comin’ Love’ after hearing ‘Not So Sweet Martha Lorraine’. Listen to them side by side and you can hear the similarities in the chord progressions. I had the good fortune to play it with Joe McDonald in the All Star Band.

There isn’t much known about your career after that with the exception that you played with Steamin’ Freeman. Tell us about him.

He was a fiddler/accordionist and we played gypsy rock. We had a four-piece band and the drummer and I had formerly been with Country Joe. We played to packed houses at a place called Mooney’s Irish Pub in San Francisco’s North Beach. There was a “fan-in-chief” there by the name of Martin Falarski, who orchestrated audience responses, complete with props and hand jive. I married him and we’re still together.

What else occupied your life after that and what projects am I missing?

Describing the bands, albums and studio work I did after Country Joe is impossible to do succinctly. Instead, I refer your readers to my growing website dorothymoskowitz.com, where I will be posting more about Steamin’ Freeman, The Out of Hand Band, my jazz singing with pianist Dick Fregulia and my children’s recorded and performed works.

Nearing 60, I returned to school for a degree in music education and spent twelve years teaching beginning brass in the local school district. In my 70’s, I began formal viola study and played with a local woman’s orchestra, continuing with chamber groups when COVID restrictions limited us all.

Is there any unreleased material that you would like to see being released?

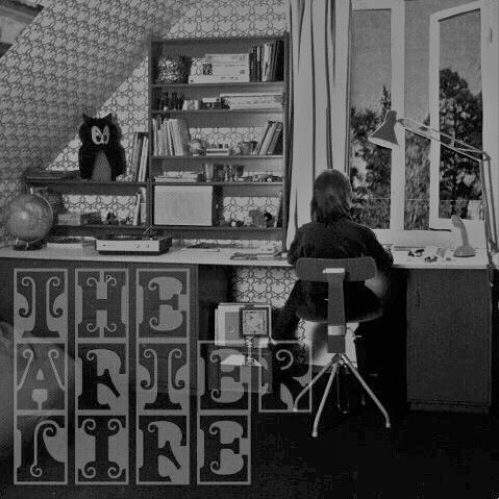

‘The Afterlife’

This is the fully realized double album I did with the Swedish composer Retep Folo (aka Peter Olof Fransson). It’s brilliant and unique. Peter describes it as having elements of dystopian concerns, uplifting nature celebrations and touches of the paranormal. He wrote and played all instruments, I did vocal melodies and narration. Spectacular.

‘Drifting Fires’

I worked with Yuriko Doi, artistic director of Theater of Yugen in San Francisco, composing fusion music for her Noh and Kyogen works. I’ve added new instrumentation to my original vocal recordings here. The poetry is by the noted translator and scholar Jeanine Beichman.

‘Perfect Rose’

This is a collection of songs originally written and recorded in 1989 for a public radio documentary about Dorothy Parker. I embellished her poems and aphorisms with lines of my own. Much of Parker’s verse has recently entered the public domain, so the time is ripe.

‘Rising To Eternity’

This is my first solo album. It’s an electronic tribute to the WEBB Telescope, launched on Christmas of 2021. It’s slated for release on the second anniversary of the launch this December, but I mention it here in the hopes that we have a second interview where I can go into more detail.

‘Secret Life Of Love Songs’

I mentioned my collaboration with Tim Lucas earlier. The CD was a limited edition and I hope we can reissue it so that the music reaches a wider audience.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

The brightest musical highlight was not in the rock or jazz scene, but in my local school district. My colleagues found support to mount extravagant musicals for the middle school, hiring a professional arranger for the 65-piece youth orchestra that backed 100 children on stage, all performing my songs. All the conducting was of conservatory quality. I thank my music colleagues Cathy DeVos, Mary Ann Benson and Leonora Gillard for making it happen for five unforgettable years. They may not be as well known as the acts I worked with, but they ought to be for all the hearts of the children they helped me touch.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thanks so much Klemen, for inviting me to give such detailed responses to questions I wished had been asked of me years ago. I’ve had to skip some, simply because I’ve forgotten things. I hope you and your readers find what I’ve come up with a fresh glimpse of where I began and of where I think I’m headed.

Klemen Breznikar

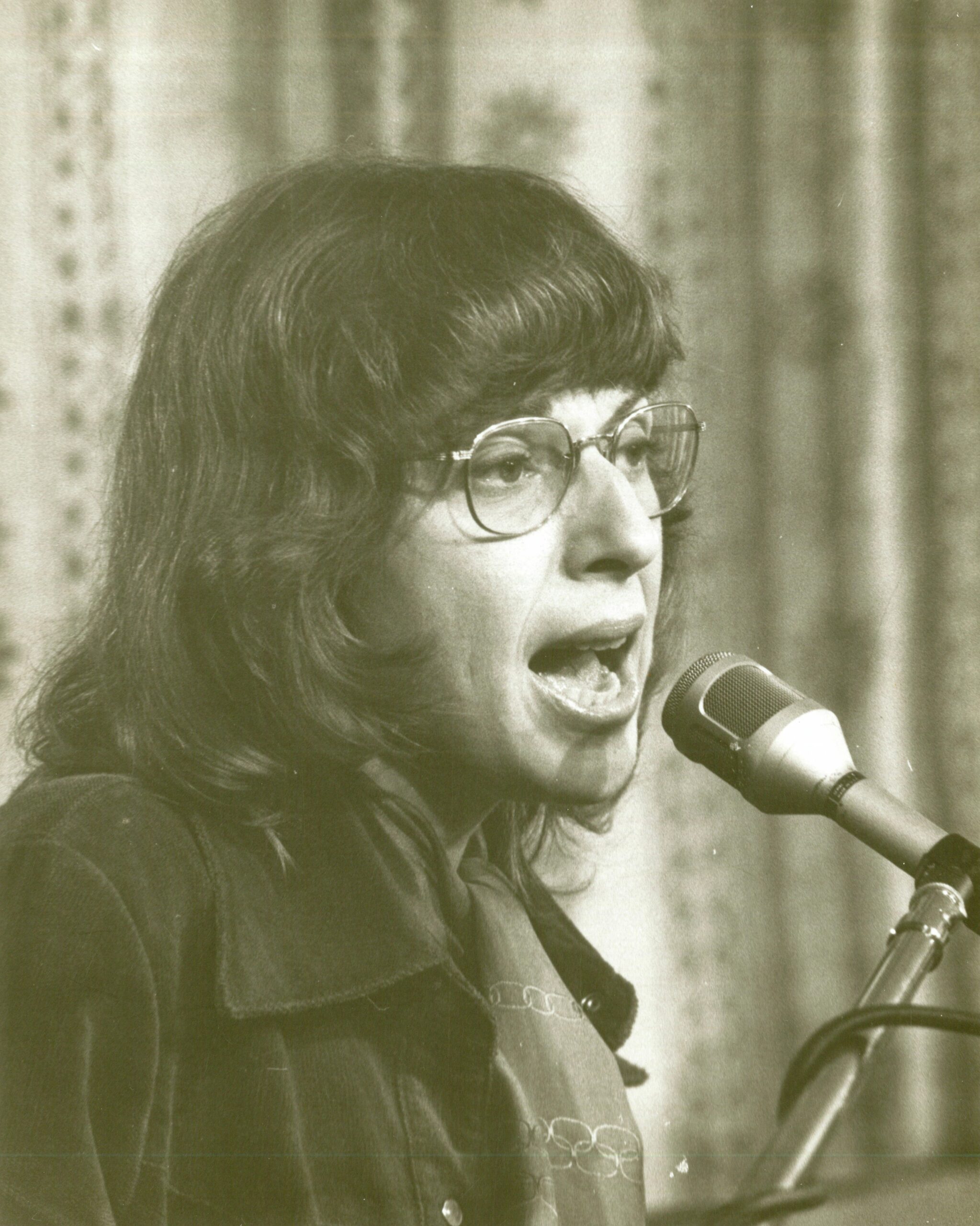

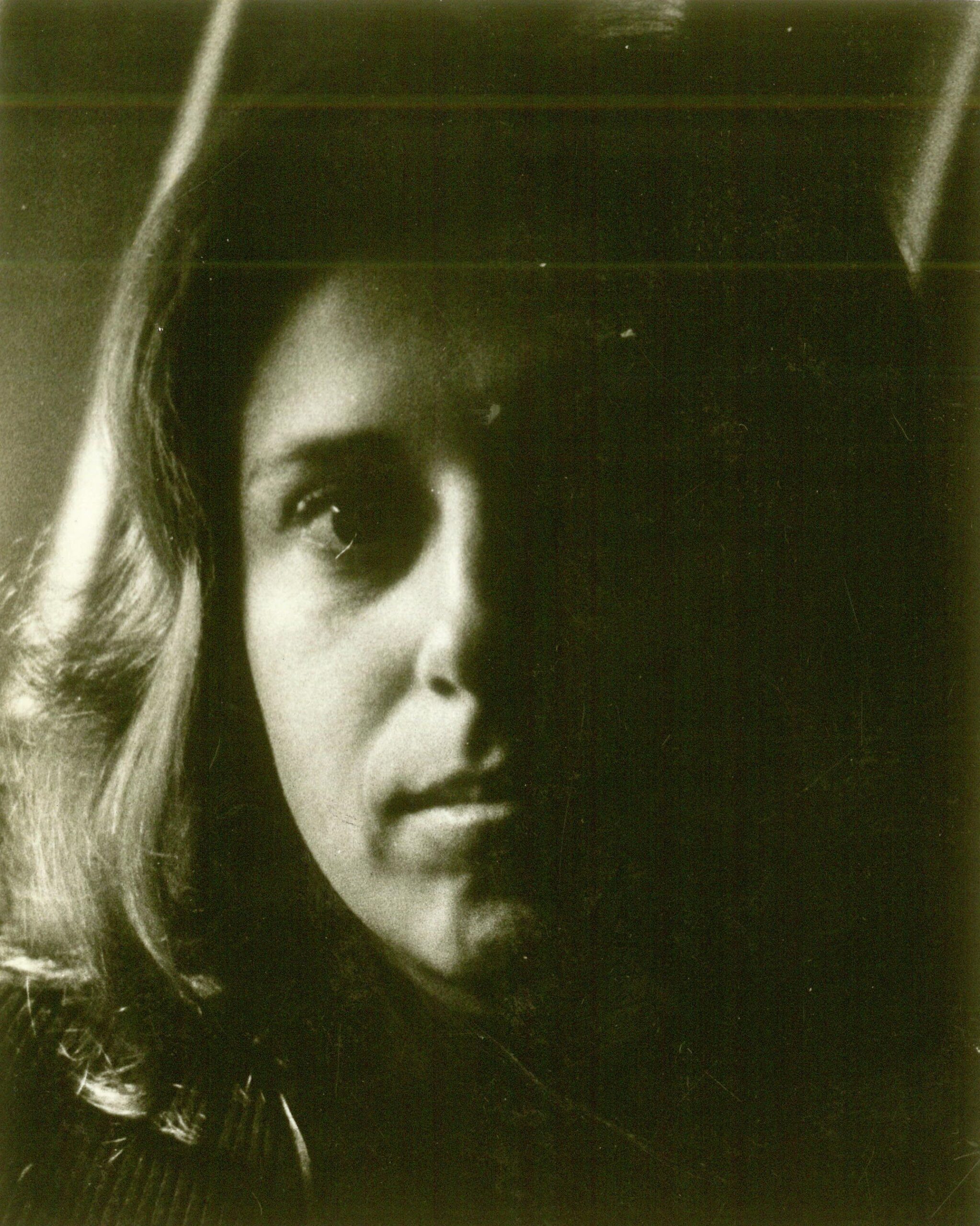

Headline photo: Dorothy Moskowitz in the studio (late 70s)

Dorothy Moskowitz Official Website

Tompkins Square Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / SoundCloud / Twitter / YouTube / Bandcamp

The United States Of America | Joseph Byrd | Interview

Country Joe and the Fish interview with Joe McDonald

One of my fave interviews in the site. As a big The United States of America fan it’s a delight to read an interview of Dorothy Moskowitz here. She had one of the loveliest voices in Popular Music. It’s nice to see she’s a gracious lady who is generously willing to share her storied musical careerr here. It would be nice Klemen if you could do another interview with her as she has more stories to tell which her fans here would be pleased to know.