Norma Winstone | Interview | “I think the only way to learn is to be obsessed”

In a career spanning more than 50 years, the British jazz singer and lyricist Norma Winstone is a true legend. She is most well known for her wordless improvisations.

Musicians with whom she has worked include Michael Garrick, John Surman, Michael Gibbs, Mike Westbrook, as well as pianist John Taylor, to name a few.

“I think the only way to learn is to be obsessed”

It’s really an honour to have you. How did you spend the last three turbulent years? As an artist, have you found the isolation creatively challenging or freeing?

Norma Winstone: I did actually manage some concerts in Italy in between their lockdown periods. I also spent time going through John Taylor’s music which I acquired after his death and made sure that all his compositions were saved on the computer. I would love eventually to create a book of his compositions in his own handwriting, which was beautiful. I did not really find the isolation “freeing” however.

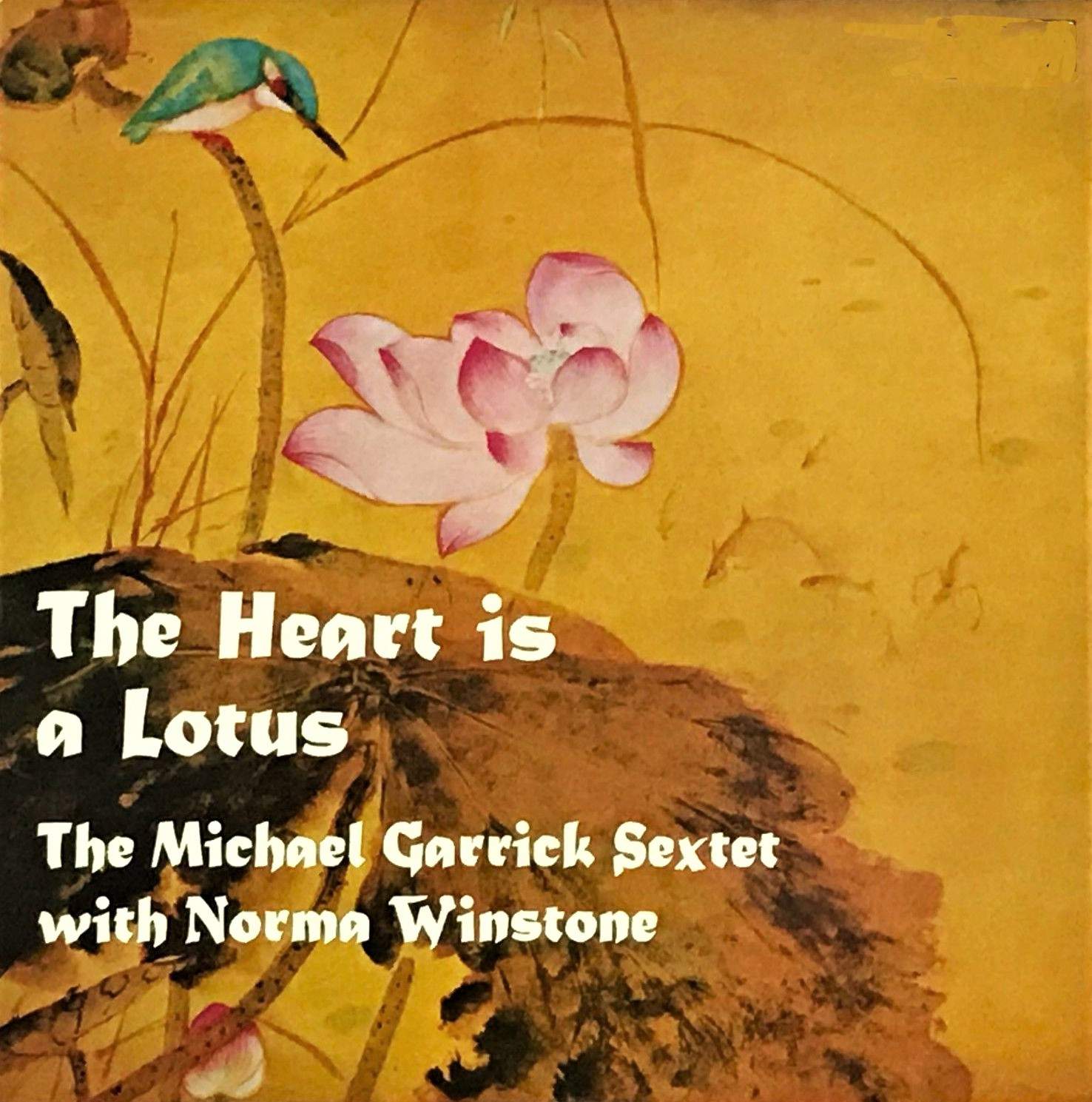

Tell us about the collaboration you did with Michael Garrick Sextet. It also featured Don Rendell, what do you recall from the session?

The ‘The Heart is a Lotus’ was actually the first recording I made as part of Michael Garrick’s Sextet. I don’t remember much except that recording was quite a new experience for me then so I probably wasn’t as relaxed as I would have liked.

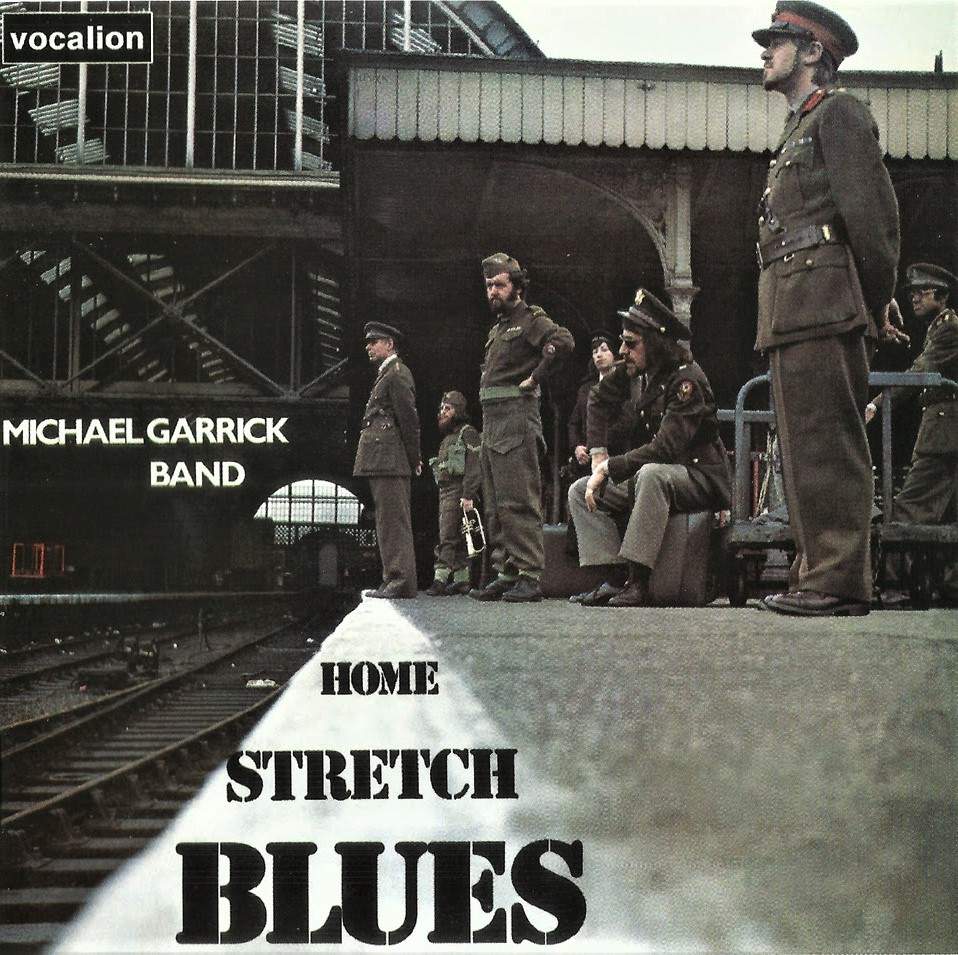

‘Home Stretch Blues’ was much later and featured Art Themen, Henry Lowther, Dave Green and Trevor Tomkins who were the regular members of the sextet, and Michael Garrick of course and I remember Don Rendell being on some tracks. I also remember that for the photo session for the album sleeve Michael Garrick wanted us all to dress in World War II uniforms and created a scenario for why we were all together on a station platform (Kings Cross in London). That was Michael Garrick! Never short of unusual ideas and there was a great feeling of camaraderie amongst the group so we happily went along with it.

ECM released such a fantastic album that I can’t get over it. What was the process of recording ‘Descansado’?

‘Descansado’ was the fourth album the trio of myself, Glauco Venier and Klaus Gesing recorded for ECM. We had only recorded as a trio before, but decided to add cello and percussion for this one. Glauco Venier had the idea that we could find some interesting material in music from the movies. He is Italian and of course there has been some wonderful music for Italian films. We identified music that we liked and where necessary I came up with lyrics. The recording process was the same as usual in that we were together for two days recording and a day mixing in Stefano Amerio’s studio near Udine, Italy with Manfred Eicher producing.

You instantly recognize when you hear Miles Davis playing and I feel the same when hearing your voice. You have a very unique style that can be recognized from the first few seconds. Was that something you thought of when starting your career or did it all come naturally? Speaking of Davis, he must have been an influence?

Miles Davis was certainly an influence from when I was first interested in jazz and knew that I wanted to be a singer. I had heard Frank Sinatra of course from a very early age and adored his singing. Later I heard Ella Fitzgerald scat singing and loved it and tried to copy what she sang. I then listened to the Dave Brubeck Quartet featuring Paul Desmond and had no idea that they were improvising. What Paul Desmond played was very singable and I assumed that it was written. I played the record over and over and would sing along with Paul Desmond’s solos. I read somewhere that they were improvising which was a revelation to me.

Then came ‘Kind of Blue’ and I realised that that was the kind of music I would love to sing. Of course I had no idea how that could ever happen as I had only ever heard singers singing the melody and the other musicians taking solos. When I began to try to sing in public I began to alter the melody on the second chorus whilst still singing the words and I guess that was how I began my own improvisations.

As far as how the sound of my voice later developed I think I was greatly influenced by singing with Kenny Wheeler. How fortunate I was to sing with him and unconsciously, I think, try to match his sound with my voice.

How would you describe your relationship with words?

I love singing words as long as they are good. I began writing words when I wanted to expand my repertoire to something beyond the standard songs of The Great American Songbook. I had heard beautiful compositions by Ralph Towner, Egberto Gismonti, Steve Swallow, John Taylor and Kenny Wheeler of course. These had no words, but I wanted to sing the music so I tried my hand at writing words for them. I had always loved poetry but had no idea whether I could do justice to these lovely compositions, so I tried and it became quite a thing for me.

“To find a way to express something deeply”

Back then when you started your career there were no academies for jazz music. Everything was derived from the artist’s love to experiment, to find something new. There were no particular rules. Do you think (and I really do), that musicians back then were way more creative in a way that they recreated their own world?

It’s true that there were no schools where one could learn about jazz. The only way was to listen to the musicians that could really play this music. I know that I was obsessed with music I heard that I loved. (I also loved classical music by the way.) I think the only way to learn is to be obsessed. My idea was not necessarily to find something new but as a singer, to find a way to express something deeply felt in the way that I heard instrumentalists doing. I’m not sure that back then musicians were more creative, I just happened to meet dedicated, serious musicians who were perhaps more interested in creating their own compositions than playing somebody else’s. I was lucky.

Would you like to take us back to your days of singing at Ronnie Scott’s? What was that experience like for you?

I had not made a name for myself on the London jazz scene when I auditioned for Ronnie Scott. He heard me and offered me a 4 week engagement at the club which was both terrifying and exciting. I played with the great Gordon Beck on piano, Alan Ganley on drums and Ken Baldock, bass. In fact it was through drummer John Stevens, who eventually created the Spontaneous Music Ensemble that it happened. I had not met him before but I “sat in” in a club where he was playing and he immediately said that he would ask Ronnie Scott to audition me. He set up a group for me to sing with which consisted of himself, Gordon Beck on piano and Jeff Clyne on bass. However it took a long time to arrange the audition with Ronnie Scott and by the time we got a date John Stevens had discovered “free” music and did not want to play time. So Gordon Beck booked a new drummer who had just arrived in London, by the name of Tony Oxley! What an audition trio! What an opportunity to sing six nights a week in such a place. A real chance to learn and practise. I think such opportunities no longer exist unfortunately.

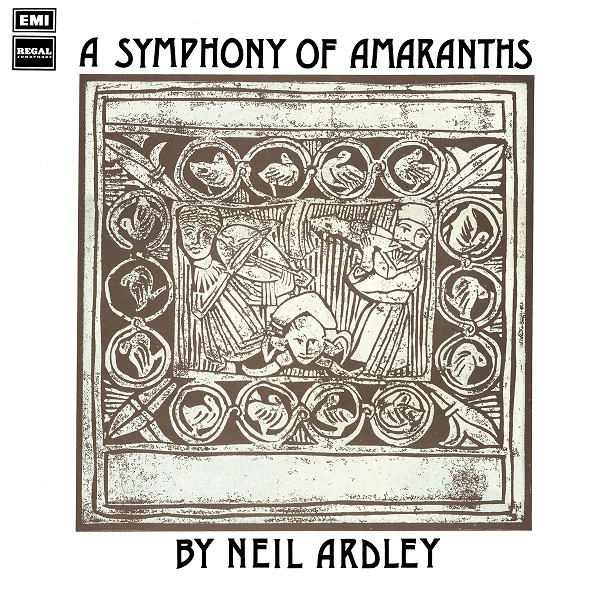

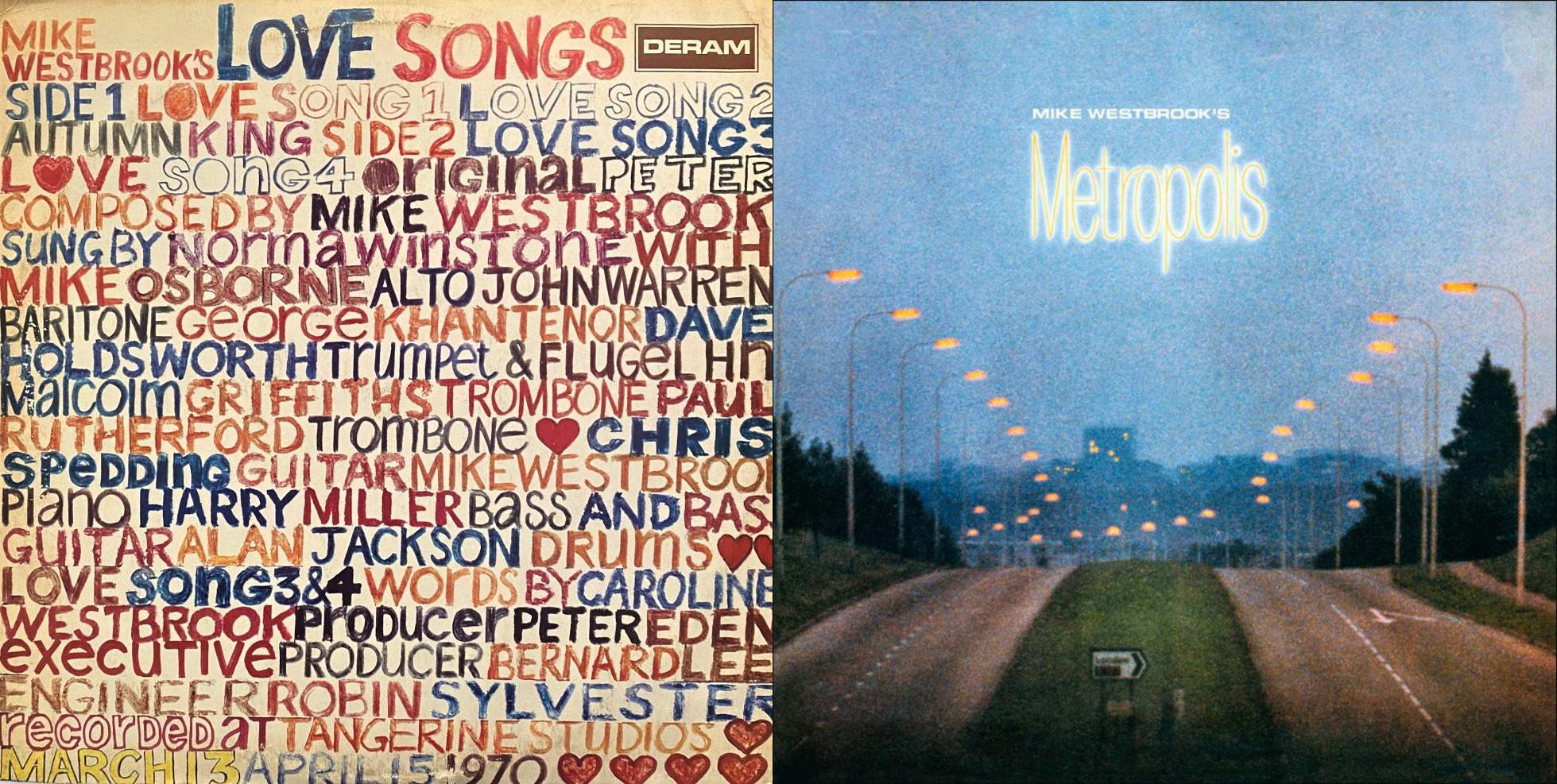

I would love it if you could talk about the involvement with Mike Westbrook and Neil Ardley?

My involvement with Neil Ardley began when I met trumpeter Ian Carr who said that he thought I should sing with the New Jazz Orchestra and he would introduce me to Neil Ardley. This he did and I began to sing with the orchestra. I had never sung with such a large group so that was a new experience. Also Neil Ardley was at that time transcribing some Gil Evans arrangements and I got to sing ‘Buzzard Song’ from the Miles and Gil recording of ‘Porgy and Bess,’ which I was in love with, so again I couldn’t believe my luck. Neil Ardley also involved me in recording some of his poem settings as well as his compositions. All these things were new experiences which I was thrilled to be involved in.

My association with Mike Westbrook began when he asked if I would like to be in a project called Earthrise. He had written music after the moon landing (1969?) for a fairly small group. Mike Westbrook was very creative and I found myself involved in some very unusual projects one of which was based on a Mayan calendar. There were three areas on the stage and each member of the group had an allotted time in each area (I think it was an hour in one, 20 minutes in another and 40 minutes in the third). We could do or play anything we liked in our area and of course we overlapped with each other. The whole thing went on for a couple of days if my memory is accurate! Mike Westbrook was and still is quite a force and always seems to come up with new ideas for projects.

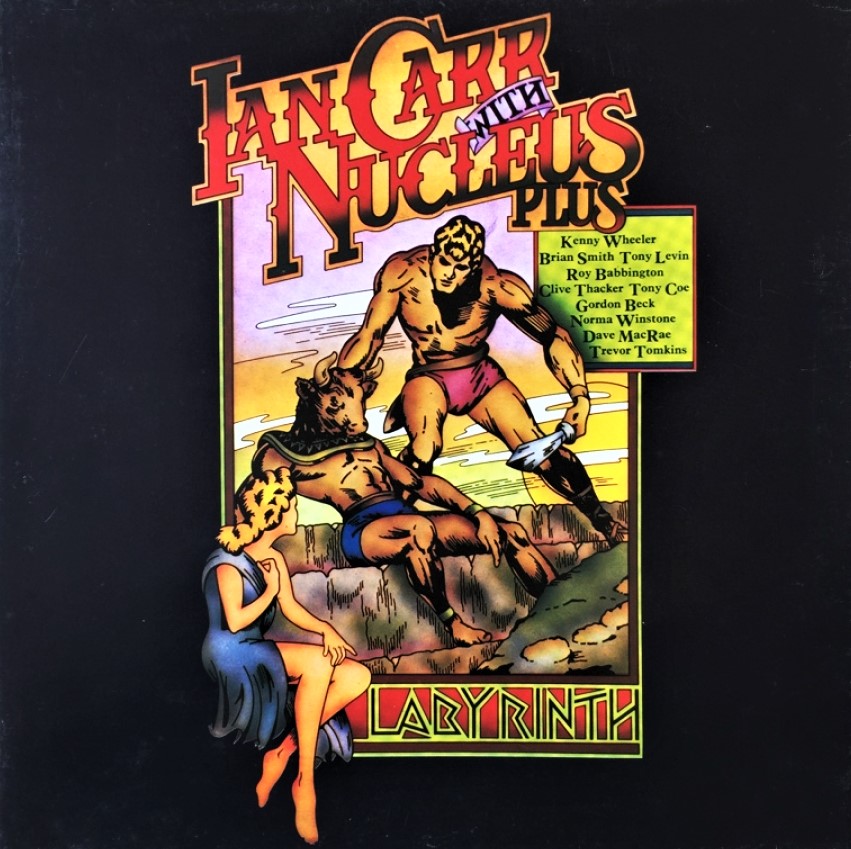

You also worked with Ian Carr’s Nucleus on the 1973 release ‘Labyrinth,’ a concept album based on myth about the Minotaur. Any recollections of those sessions?

I seem to remember I was pregnant at the time of the recording. Other than that I don’t remember much except that it was great to have both Kenny Wheeler and Tony Coe making their predictably wonderful input. It was quite a different kind of music than I was used to being involved in but I always loved a challenge.

You collaborated on so many records that it’s literally impossible to discuss everything. Do you have any collaborations that stayed really close to your heart?

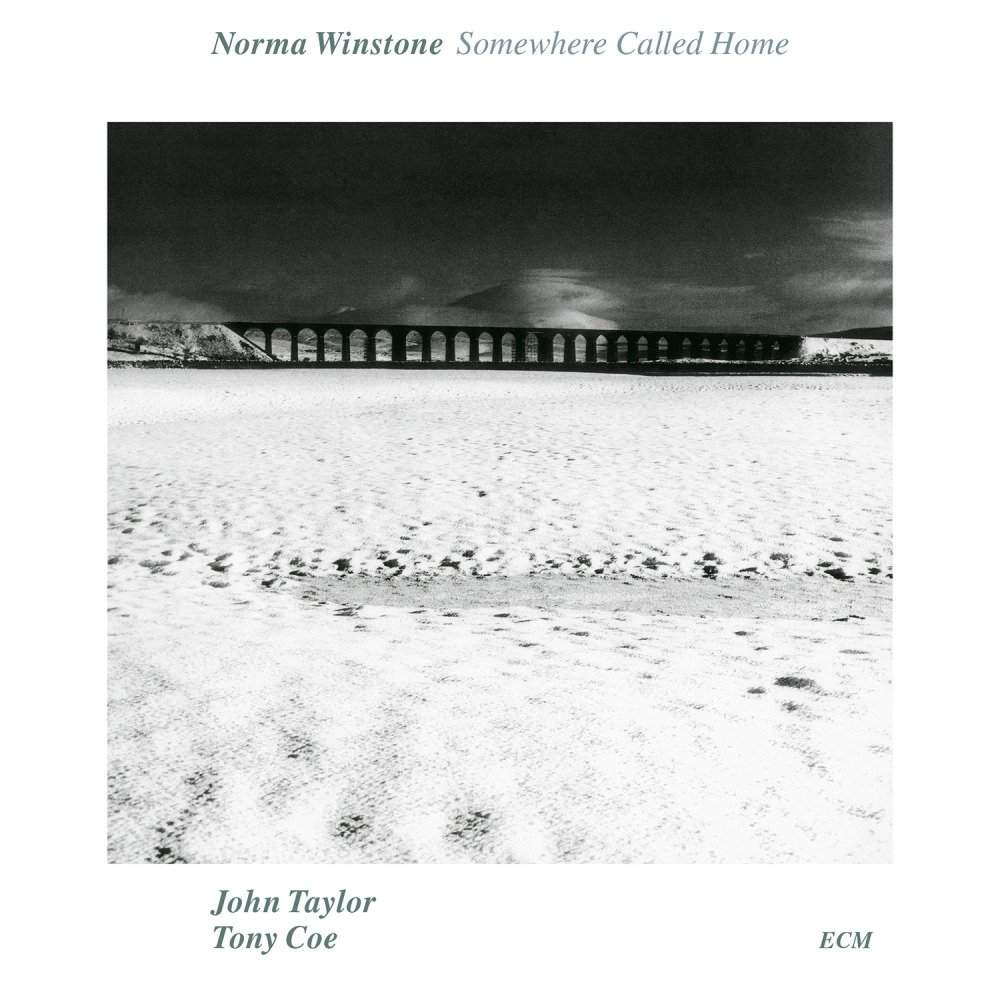

Of course ’Somewhere Called Home’ was special. The first ECM recording in my name and two of my favourite musicians to record with. The first Azimuth recording was an unforgettable experience. First time meeting Manfred Eicher and as it happened Ralph Towner was around and popped into the mixing session so we met him for the first time too. Also it was on listening to the playbacks that I realised that I could bear to listen to my voice! I had never liked the sound I made and I think that this was the first time I had been recorded sympathetically and was aware of Kenny Wheeler’s influence on my sound.

Also the recordings with Glauco Venier and Klaus Gesing will always be special to me. Another lucky collaboration.

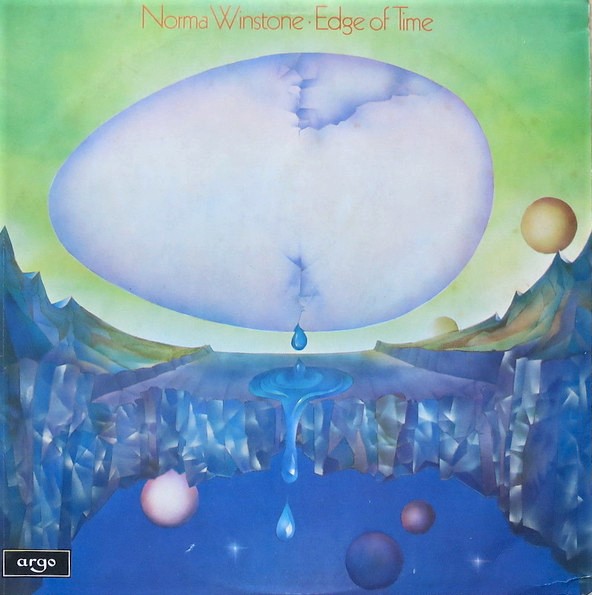

What are some of the strongest memories from working on ‘Edge of Time’? Was there a certain concept behind it?

I had won a Melody Maker poll and the Decca record company offered me a recording. I decided that I would include as many of my friends as possible! So the tracks went from trio to 10 piece groups. There was no real musical concept behind it; just the opportunity to record in different settings. I guess it was a very unusual recording for the time and gave me the opportunity to explore different settings. Also it gave me the chance to get some arrangements by John Taylor, John Surman and John Warren.

I am sure it wasn’t what Decca was expecting and they deleted it as soon as the first batch of vinyl ran out!

What led you to form Azimuth? What was the creative process like with John Taylor (piano) and e (trumpet)?

After the ‘Edge of Time’ experience recording opportunities seemed to run out. So John Tayčpr and I decided to record some pieces in duo and he would take them to record companies (mostly in Germany it seemed) and see if we could arrange a new recording.

First on the list was of course ECM. I think that Manfred Eicher had heard of John Taylor and so he was able to get an appointment to meet him. John Taylor had just bought a synthesiser and on the night before he went he came up with a “loop” and asked me to improvise over it and he recorded it. When he met Manfred Eicher he played some of the studio recordings we had made and he seemed to like them but when he played him the little recording with synthesiser Manfred said, “I can hear a flugel with the voice. Let’s involve Kenny Wheeler also in the recording”. So really Azimuth was Manfred Eicher’s ”creation.” We didn’t have a name then of course but we recorded the synthesiser piece in the studio and had to find a title for it. Manfred said that it sounded to him like a journey. So when John Taylor went through the Thesaurus looking for words connected with journey / direction, he found the word Azimuth. So the synth piece was called Azimuth and that became the name of the group.

The creative process was that John Taylor would come up with some compositions, many of which we developed as we recorded in the studio. It was such an exciting process.

What runs through your mind if we would play one of the most incredible records from your vast discography, ‘Somewhere Called Home’ (1986)?

Nostalgia for those creative times and those wonderful musical colleagues.

“A world without music is no place to be”

What occupies your life these days?

Well, I haven’t retired! I have two sons and two granddaughters who occupy my thoughts quite a bit. But music still occupies my life and, I think, always will.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

A world without music is no place to be…

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Norma Winstone at home in 2016 | Photo by Michael Putland

Norma Winstone Official Website

A fine interview from perhaps the only notable female Jazz singer who sings avant-garde. “Edge of Time” is one of the essential Experimental recordings.

Norma would be in my pantheon for “Breathtaking” on AZIMUTH 85 alone, but she has done so much more which is also of merit. An endlessly creative spirit, Norma Winstone is as uniquely a first lady of British music as Carla Bley is of American music.