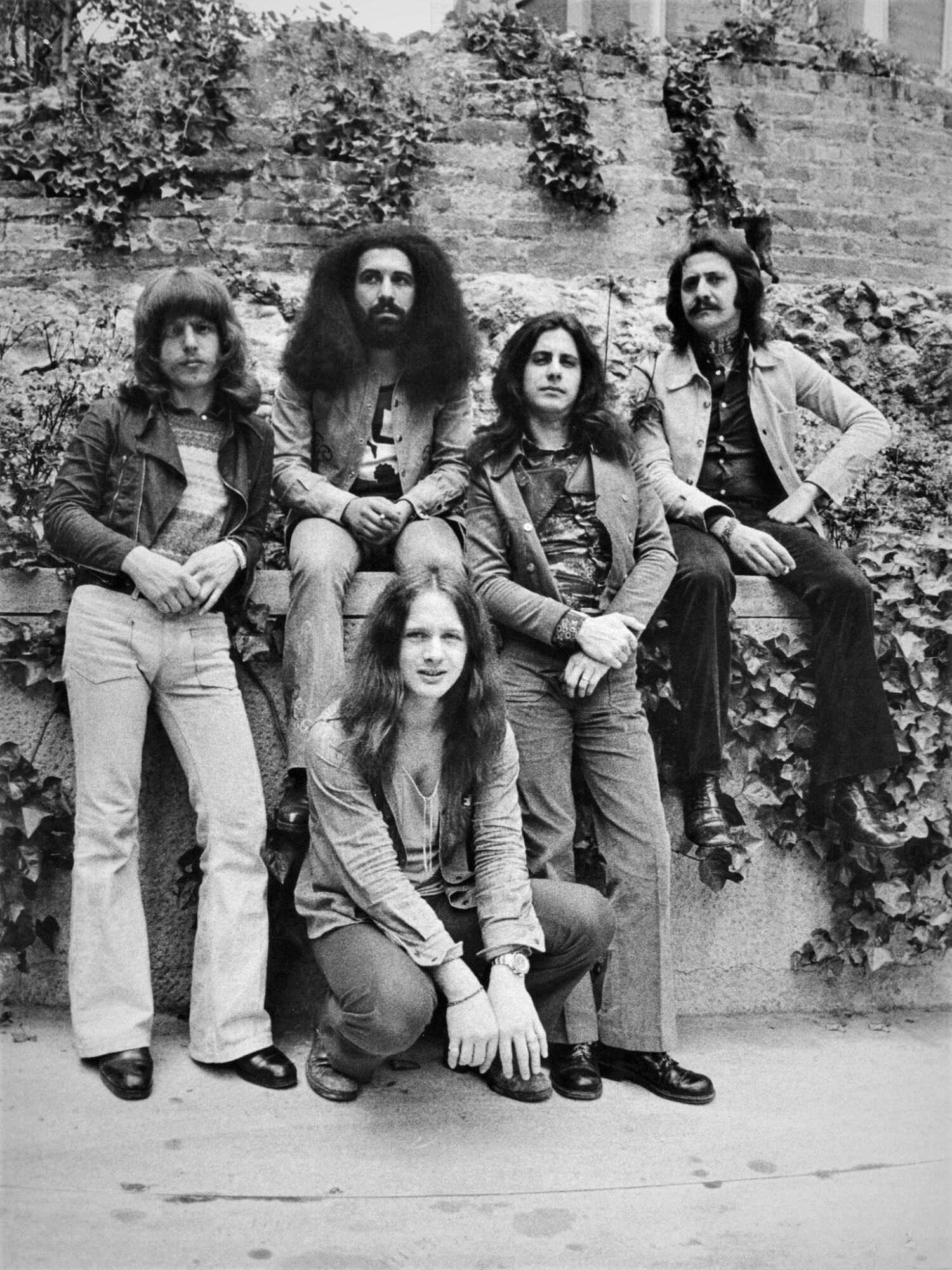

Nuova Idea | Interview | “In The Beginning”

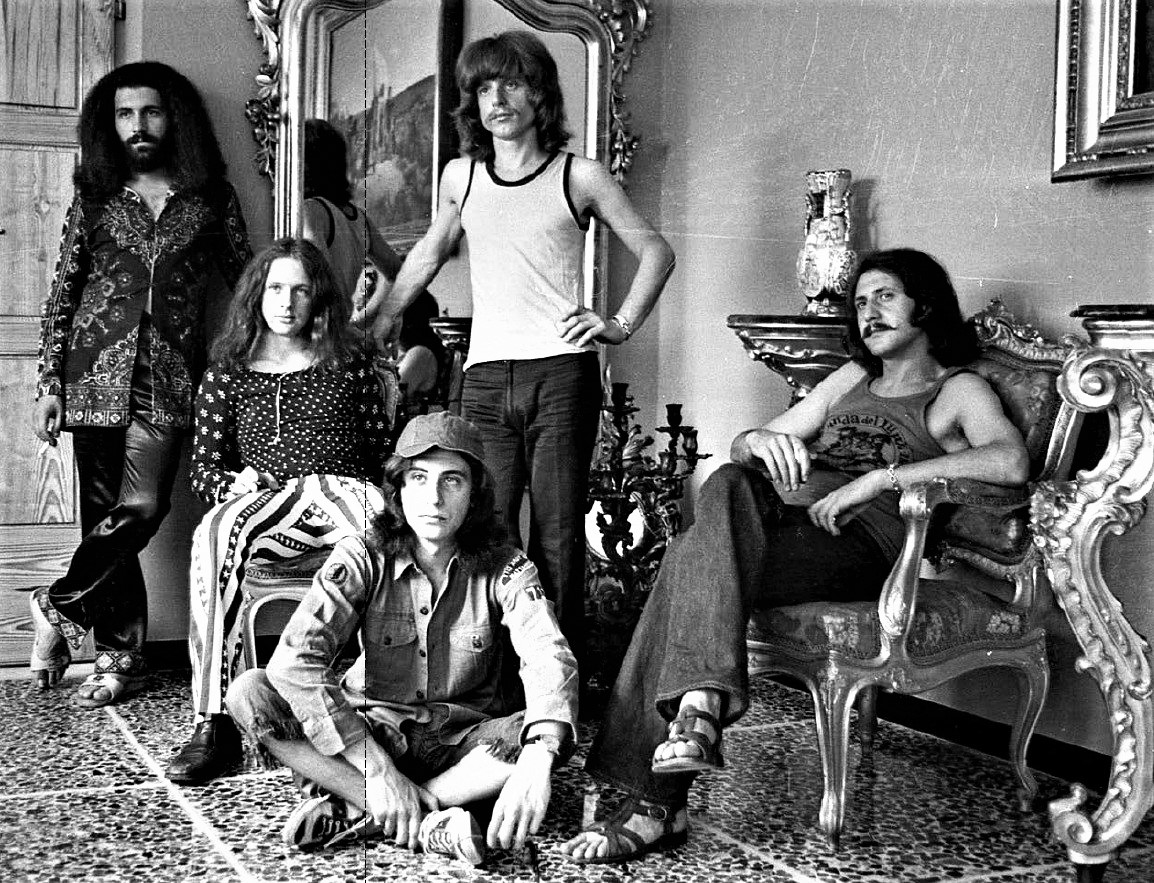

Nuova Idea was Genoa based progressive rock band that released several incredible progressive rock albums and are also behind the monikers of The Underground Set and The Psycheground Group.

Nuova Idea was born from the Genoese beat group Plep, named after the members Paolo Martinelli, Luciano Biasato, Enrico Casagni and Paolo Siani, who in 1969 changed their name to J. Plep after Giorgio Usai joined the group.

“I tend to be a lover of classicism and at the same time of experimentation”

Italy has had a lot of interesting bands since the 60s. You are coming from Genoa, what was it like growing up in the city?

Paolo Siani: Genoa is a particular city closed to the north by the mountains and open to the sea to the south. For centuries it has been the most important port in the Mediterranean and beyond, so it is inevitably the melting pot of a thousand different cultures, not to mention that until the early 1960s it was the departure point for transatlantic liners to the Americas.

This has influenced and still influences the character of a population that is essentially of few words, and complaining as all seafarers are. Even the music is influenced by this story (similar in this to cities like Liverpool): for example the use of falsetto is a particular feature of the Genoese tradition, the attention to the quality of the sounds, the search for originality, the poetics of texts that are never banal (the Genoese school of songwriters is the most important in Italy). This saying is inevitable that a young man who devotes himself to music breathes all these nuances that flow in the air. In the 60s, in every district of Genoa, more than one “complex” of young people was born who, locked up in cellars, tried to put together songs from Swinging London groups.

What got you interested in music? Were any of your family members musicians?

My uncle Alessandro lived in the U.S.A. and he was a double bass player in the Philharmonic Orchestra of Philadelphia directed by the great Leopold Stokowski and he sent us every month by sea a package of 78 rpm records of the great American Big Bands of the 50s/60s. My parents had a knitwear workshop at home with a dozen workers and to keep me calm, my mother put me in the cradle right next to a huge radio-gramophone and put one record after another on the turntable, so I can say that I was weaned on milk and swing music. Then my father, proud of his American brother, mostly gave me toy musical instruments instead of pistols, toy car rifles or anything else. I remember a baby drum kit, a colored xylophone, and finally an 8 bass puppy accordion; just with this without anyone saying anything to me, I began by ear to put together some of the easy melodies that I listened to every day. I remember in particular ‘Lisbon Antigua’ and ‘Whatever Will Be, Will Be (Que sera, sera)’.

What did your journey into music look like? Did you originally start with the drums or were you also playing any other instruments?

This spontaneous musicality naturally did not escape my parents who decided to send me to the Accordion School after having bought me a bigger (80) bass accordion. I liked it, I had started reading music and using the bass with my left hand, acquiring a certain independence of my hands but unfortunately my body was a little frail and my paediatrician convinced my parents to suspend my musical studies because of scoliosis.

“It was an explosion of joy, an unforgettable moment that thrilled me”

Would you say there was a special moment when you knew that this was it and that you want to be a musician for the rest of your life?

Years went by, I started high school and in the meantime the music of The Beatles and other English and American groups exploded and in my class, one day when they sent us home a couple of hours earlier, I went together with three other boys to Gaggero, a shop in the historic center of Genoa that rented instruments and rehearsal rooms for little money. A boy took a guitar, another a bass, another one played the piano, and me? Not knowing how to play those instruments, I sat in front of the drums. It was an explosion of joy, an unforgettable moment that thrilled me and finally pushed me to get absorbed in music.

What do you recall from your very first garage rock group Plep? Did you have any of your own tracks? What kind of material did you perform?

In a few months together with Giorgio Usai (piano) we put together a group of kids and we reached our real debut in public in a self-managed club called Little Feudo so we decided to call ourselves I Feudali (great idea, hehe). The emotion was enormous and it was on that Sunday afternoon that a journey began that has not yet ended. Subsequently, due to school commitments, the formation changed numerous times and also changed its name; Plep was an acronym of our names (Paolo, Luciano, Enrico and Paolo) and it brought us luck. We began to have requests in the various Genoese clubs and venues where we grew up with each performance because we made extensive use of polyphonic voices and because we arranged in our own way ultra-famous songs by The Beatles (‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’), The Yardbirds (‘For Your Love’), The Moody Blues, The Animals, Jimi Hendrix Experience, Cream and many more.

Did you do a lot of gigs under this name?

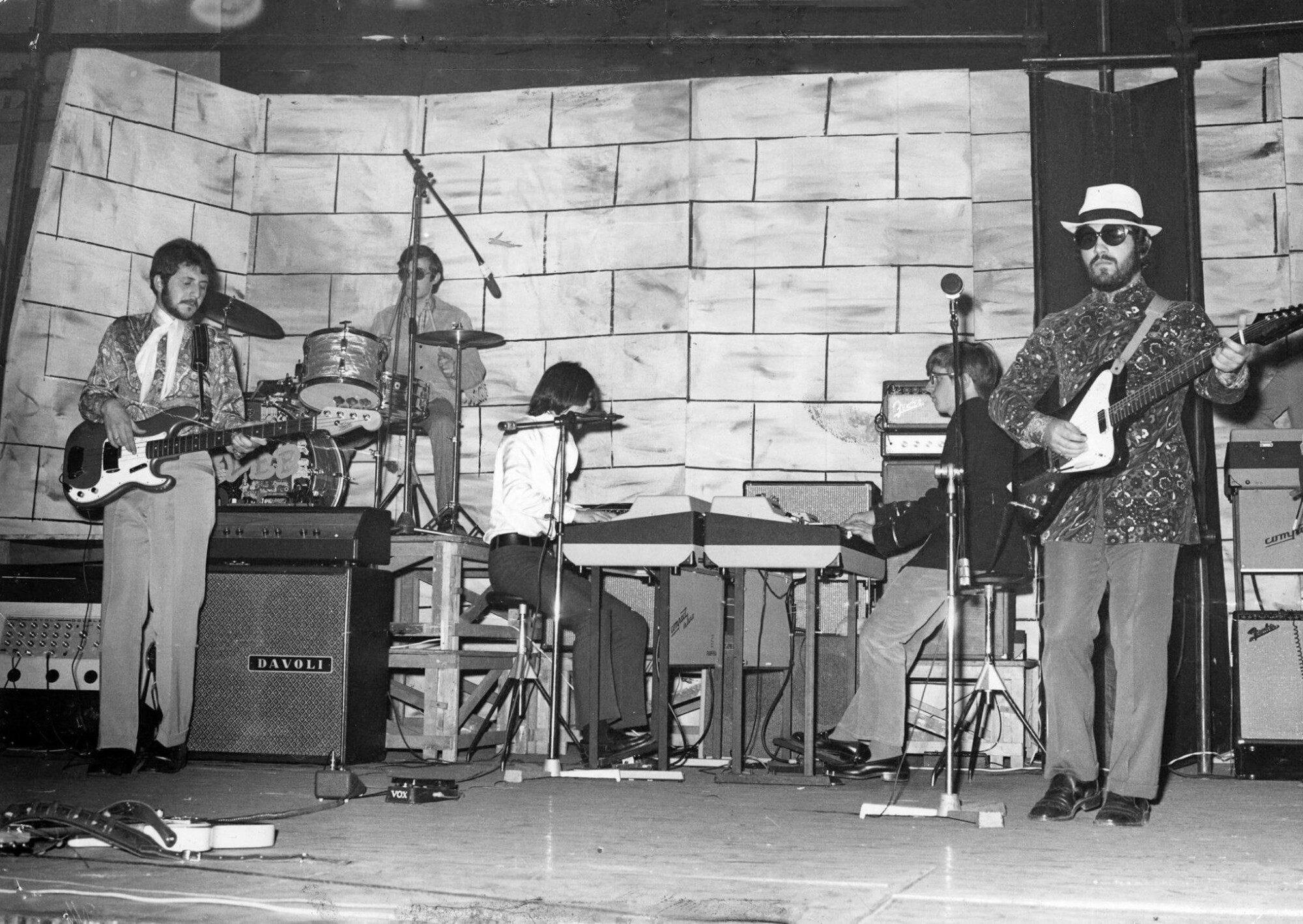

Where we played, the venues filled up and someone from the trade noticed us. At first we began to leave Genoa while remaining in Liguria, going to Sanremo, Diano Marina and other holiday resorts, then a Roman impresario took charge of us and we began to tour Italy and it was an uninterrupted crescendo of success for our performances. What they liked best about our playing was the strength with which we performed. In Naples, for example, the community of American boys literally fell in love with us and often invited us to perform for their Mac P. Meanwhile our musical tastes evolved and The Vanilla Fudge created a stimulus for us to create our first real arrangements with classical hints. Maestro Gianfranco Reverberi became our producer. He made available to us some songs that we arranged in our own way and published the first 45 rpm with the name J Plep with two songs ‘La scala’ and ‘L’anima del mondo’ for the Carousel label. We entered the national RAI radio programming but Maestro Reverberi decided that that record company was not suitable for our potential.

What led you to change your name to Nuova Idea? Did the band members change as well?

At this point we were professionals and I decided to enroll at the Niccolò Paganini Conservatory of Genoa in the United Percussion Course directed by Maestro Torrebruno, timpanist of the Teatro alla Scala in Milan and it was very useful for me to learn to read music quickly, especially in the years to come but the Conservatory Director found out I was playing rock music and I got expelled! “You are a misleading element, please do not introduce yourself again,” a completely incomprehensible nasty blow.

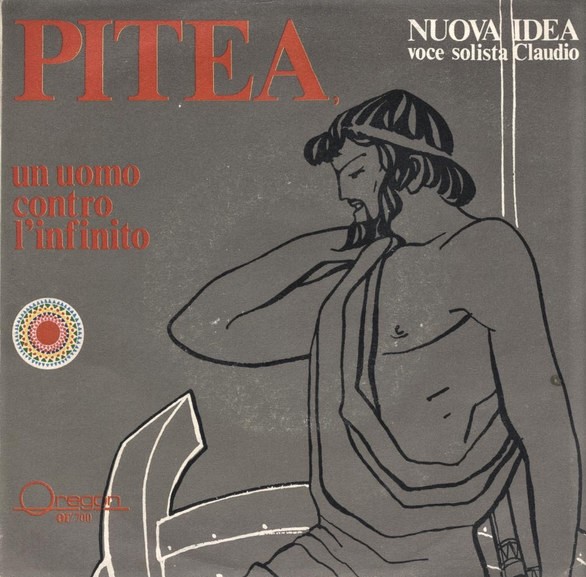

In the meantime Maestro Reverberi closed a contract with the Ariston record company which gave us the name of ‘Nuova Idea’ because for them Plep could at most be the name of a detergent (and perhaps they were right). We recorded with them ‘Pitea, Un Uomo Contro L’Infinito,’ still a piece by other authors but very suitable for our characteristics and they sent us to the Disco per l’Estate – a very important review in Italy with television and radio broadcasts. We won the critics’ prize but we didn’t make it to the final because the song was actually not entirely popular.

Nuova Idea must have been one of the very first Italian progressive rock bands.

As written above, in the meantime we had developed our own style in arranging the songs we played live and it was normal to arrive at the composition of our own songs and lyrics. In this regard we must give credit to Maestro Reverberi who made recording studios available to us to develop our unripe creativity in complete freedom, first starting from real jam sessions, then with a more precise organization starting from themes, from hints of melodies, from complex harmonic turns.

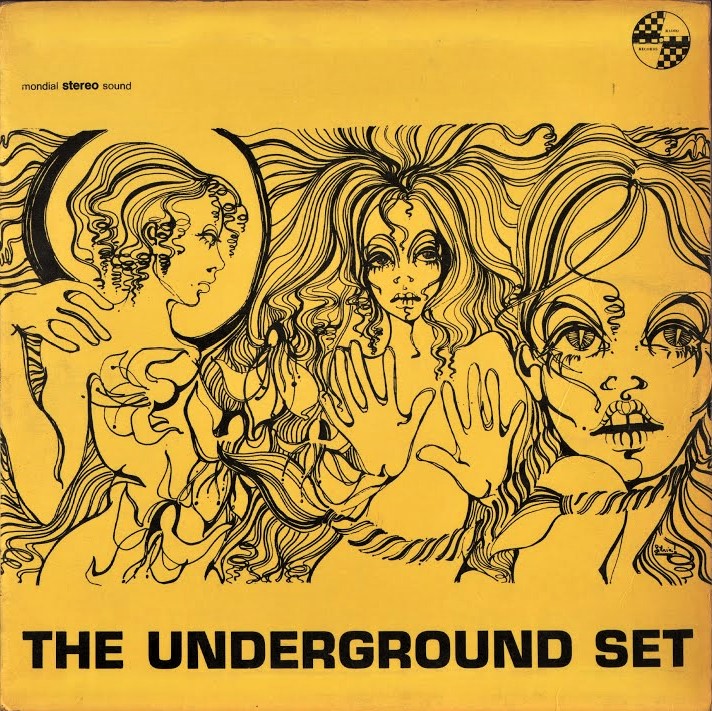

Correct me if I’m wrong, but at first you performed and recorded two albums under the name of The Underground Set? What was the contract that forbade you to use the name Nuova Idea?

In this context, many of the songs that we recorded on the two albums were born under the pseudonym of The Underground Set because for contractual reasons with Ariston we could not use our images or the name Nuova Idea.

The same thing happened to a record we know as ‘Psycheground’ by The Psycheground Group. Do tell us more about this particular session and how this infringement happened?

Subsequently, an album of real jam sessions improvised in the studio was released to which Maestro Reverberi added melodies to publish them under the pseudonym ‘Psycheground’. We didn’t know all the mechanisms related to publishing contracts, to the music industry whereby we were somehow cannibalized by the labels that released these albums: we were paid as performers and that’s it.

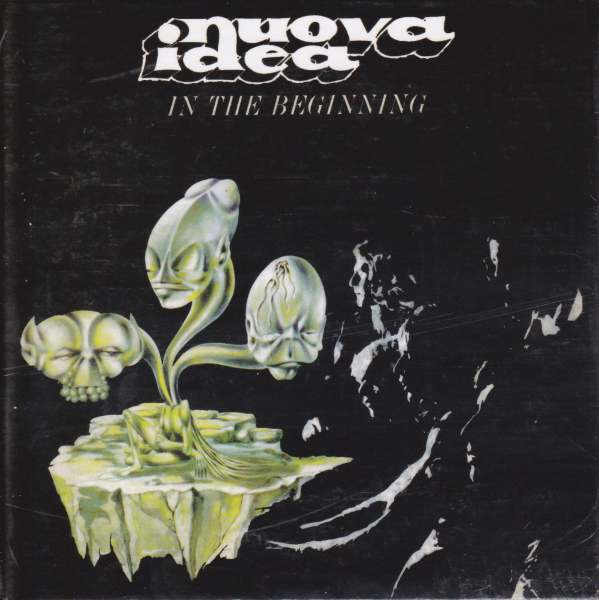

Tell us about the writing and recording material that ended on your ‘In the Beginning’ album?

The background was that in Viareggio in 1971 they were organizing the First Pop and New Trends Festival, an event never seen before in Italy which was to be held between 27 May and 2 June of that year and Ariston informed us that they had registered us among the participants.

We felt that event in a particular way and decided to lock ourselves in a rehearsal room and produce a piece-suite that would last for the whole time (about 20 minutes) of our performance on stage; thus was born ‘Come, Come, Come… (Vieni, Vieni, Vieni…),’ a pop version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. In a recording room with very scarce means (we used a three-track recorder) we managed with great difficulty to put together what for us was the audition of the suite to have it listened to in Milan by the record company. The day of our performance in Viareggio arrived and we surprised everyone a bit, the public and journalists by presenting a single piece complete with solos, tempo changes, jazz parts, symphonic parts, vocal parts, et cetera and we achieved an important success.

Subsequently, after one of our concerts, a boy approached us and asked us to autograph the 33rpm he was holding under his arm: but which record was it!?

Ariston had wasted no time given our success in Viareggio and, without telling us anything, published ‘In The Beginning’ (the title and cover were also their own invention) in which on the one hand there were pop songs that had come out previously as singles and on the other side the entire side contained the audio of ‘Come, Come, Come… (Vieni, Vieni, Vieni…)’. I know, this story may seem unreal but it is the absolute truth. We would have liked to re-record the Viareggio piece with professional means in Milan and we had also thought of superimposing parts with a real orchestra especially in the final part but it was not possible, the games were done.

It is worth pointing out that until the Viareggio Pop Festival our record company, Ariston in Milan, probably hadn’t realized that Nuova Idea was not a Beat group and that, while not proposing popular songs, we had an important following of the public.

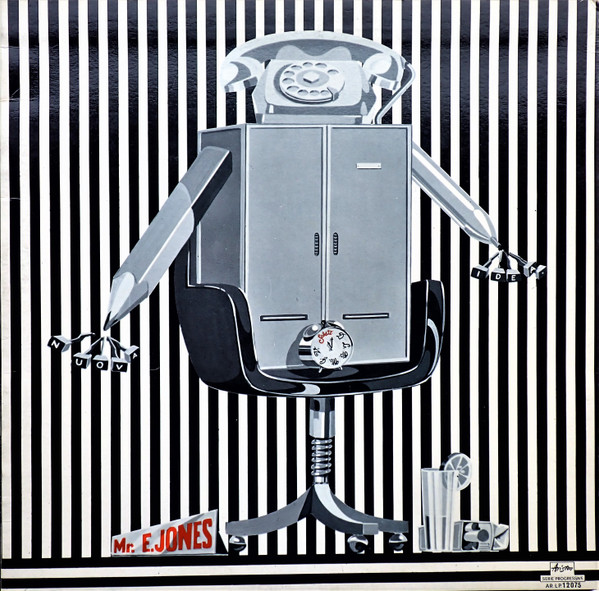

Further down the road you released your second album, ‘Mr. E. Jones,’ which clearly shows evolution in the band sound-wise and it features fantastic cover artwork. Please tell us about it?

In the meantime we did many things but we also found the time to create the second album ‘Mr. E. Jones,’ a concept album about an employee’s day. In the meantime, the formation saw the exit (by his will) of the historic guitarist Marco Zoccheddu who was replaced by Antonello Gabelli. It was a long and difficult job because at first we had to find a sound and a style which, by changing the guitarist, was not completely defined. This album was finally promoted by Ariston with great force. Prime time TV on Saturday with the intervention of an orchestra, other television broadcasts, articles in newspapers, not only musical ones, et cetera. The cover was the work of an Ariston designer (a certain Zanini) who had also designed that of ‘In The Beginning’ but this time on a theme. In ‘Mr. E. Jones’ we all changed our way of playing because with Antonello Gabelli we reinvented sound, vocality and way of writing songs. As far as I’m concerned, my drumming was inspired by that of Michael Giles (King Crimson), with the voices and instruments we looked for more dissonant harmonies than in the past and the album became the most appreciated and sold.

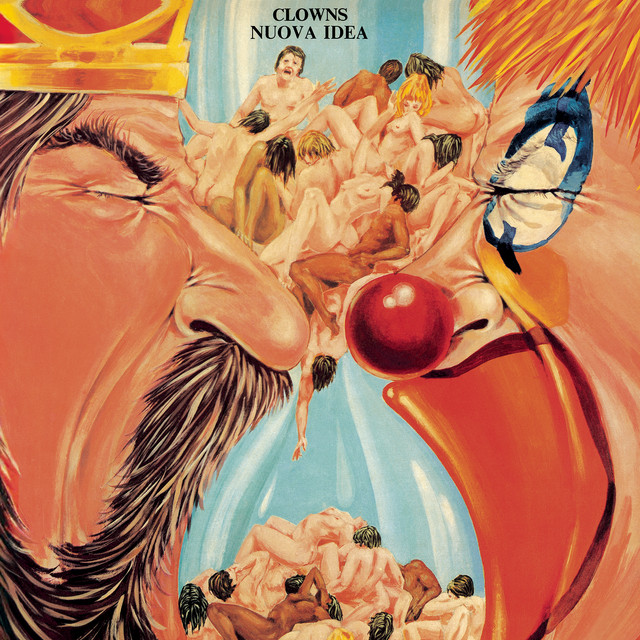

‘Clowns’ is a full throttle progressive rock with the addition of singer Ricky Belloni. He added something special to the recording. Please tell us about the recording of ‘Clowns’.

Before talking about ‘Clowns’ it is worth mentioning a couple of episodes that changed the relationship between us and between us and the Ariston record company. The first is that relations with the guitarist Antonello Gabelli went very well on a musical level (‘Mr. E. Jones’ was the most striking result) but human relations did not go as well (needless to underline the reasons) to the point that immediately after the direct television with the orchestra on RAI TV there was a huge argument in front of the hotel in Naples after which our collaboration with him was interrupted with immediate effect.

The second episode after the arrival of Ricky Belloni in place of Antonello Gabelli, was that Ariston, given the sales success of ‘Mr. E. Jones,’ wanted to continue with the same promotional power also for the following album, but in a way that we didn’t like at all. In fact, the President himself welcomed us to his office in Milan to present us with the sample of a song written by I forget who, with which he announced triumphantly that he would send us to the Sanremo Festival (the largest Italian musical event).

Unfortunately our youthful stubbornness in wanting to follow our musical ideas led us to refuse the offer that millions of Italian musicians would have jumped at and which also caused a definitive break with the record company. With hindsight I say that we should have seized that opportunity perhaps by making an effort to find a “credible” arrangement for that little song like other Italian prog bands did a few years later. But now the trouble was done.

Having said this, we nevertheless found an agreement with Ariston for which they financed the stoppage of our concerts for a month and a half during which, closed in a rehearsal room, we composed music and lyrics for all the ‘Clowns’ songs. The presence of Ricky Belloni helped us find our original musical strength and also less dissonant harmonies and melodies. In the recording room we then experimented with Ricky’s harsh voice and recorded the whole album in just a fortnight. Perhaps the voice was unpleasant in certain points but in our opinion that was a masterful album because it contained all our compositional experiences over the years. Ariston welcomed the new product with not too much enthusiasm, and promoted it very timidly. I like to mention a striking fact here. If you look at the cover of ‘Clowns,’ you will notice two things, side A with the clown and the king separated by an hourglass which in my opinion is a beautiful design and the inside completely white and very sad; we paid for the external one, the Ariston internal one!!!!

My experience with Nuova Idea, which had almost been my family for many years, was running out: quarrels, misunderstandings and above all a drop in the number of evenings convinced me that staying professionally would not allow me to build something positive.

For this reason, in agreement with the Artistic Director M° Guarnieri, luckily (and perhaps with some merit) I found an agreement whereby in September 1973 I became the drummer and secondly the internal producer of all the Ariston’s musical productions. I left Genoa and moved to Brescia 100 km east of Milan and that was my job for over two years (very well paid). Apart from the economic aspect it was there that I really became a full-blown professional. Until now I had played freely and without any kind of conditioning, now I worked every day with different artists and above all arrangers who had completely different needs. I found it very useful to know how to read music and I had the satisfaction of working with many successful artists.

Would you say your albums are based around a certain concept, like for instance what you did as part of Opus Avantra?

Among the very numerous works recorded there was also the one with Opus Avantra which was quite particular and complicated. In fact they had called a drummer into the studio who didn’t show up and they had the unhappy idea of recording the songs without him; in the analogue world of those years, when recording was still on tape, the “click” didn’t exist so when they asked me to collaborate I found myself with difficult pieces but above all not in time so I was able to play with difficulty with a certain fluency because the tempo of the base was not constant.

I recorded the first 45 of Matia Bazar, ‘Se mi lasci non vale’ by Julio Iglesias and other hits until I started working with Maurizio Vandelli, singer and leader of the most famous Italian beat group ‘Equipe 84’ with whom I recorded two albums ‘Dr. Jekyll E Mr. Hyde’ and ‘Sacrifice,’ the most progressive album of that group. The friendship and collaboration between Vandelli and me grew every day to the point where they definitely wanted me in training even in their lives.

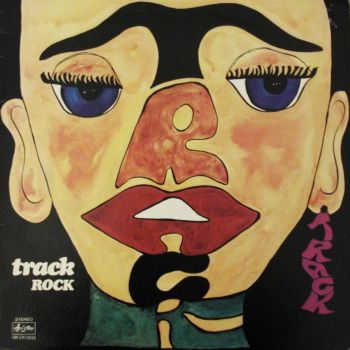

I was in full creative period and in the spare time between one recording session and another together with Ricky Belloni and Guido Guglielminetti on bass, I put together a dozen covers and ‘Track’ was born, a group wanted by the Ariston Foreign Office.

I also tried, somewhat following the tastes of the times, to compose an instrumental piece with the use of the MiniMoog as a “one man band” since I played all the instruments (apart from the orchestra of course). ‘Bubble gum’ was the title of the song and it was a real international success especially in Italy as well as in Germany, Spain and South America. The name of the group I invented, ‘Papy, Mamy & Son’ using my images, my wife’s and my first child.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

Having started listening to music in my cradle, the influences that have shaped my musical tastes are endless. Since I was a child I have adored some romances by Verdi, Puccini and Donizzetti in the same way as I have always adored authors such as Gershwin or Ravel. I tend to be a lover of classicism and at the same time of experimentation, of modernity and therefore, for example, speaking of my instrument I learned a lot from a brilliant drummer like Max Roach with his odd tempos, Ginger Baker for the use of the two bass drums and for the musicality of his rhythmic designs. Going back Ray Charles made me fall in love with the blues while groups like The Moody Blues, The Yardbirds, Traffic and many others from the period of Swinging London up to the first formation of King Crimson have forged my way to play which is made up of few technicalities, a lot of cleanliness and a certain strength in marking time.

What followed post-1976 for you?

The musician’s work is fascinating, wonderful but in my case I realized that while I was at the peak of my career as a musician, I felt at the bottom of the charts as a father because I realized that I was totally neglecting my son Luca. It was a slow and very difficult choice but, while the phone rang more and more frequently with continuous requests for collaborations and work, I felt compelled to make a choice: either to become a rock star by abandoning the family or to become a good family man. The choice was the latter, I gave up everything from one day to the next, I opened a commercial activity and began a less eventful life. I must say that I have no regrets also because the music I had made up to then I have the presumption to affirm that it was of quality. I abandoned the profession of musician but I didn’t abandon music, on the contrary I devoted myself to the study of electronic music in a serious way (something I had always had in my heart) and I still keep a good library of texts mostly in English with biographies, studies, experiments of almost all the authors of contemporary music. In those years I also dedicated myself to the production of incidental music for several theatrical works including my multimedia concert for electronic music, percussion, choir and dance.

You know, I really enjoyed the release of your solo album, which was issued by Black Widow Records. It sounds like you had a lot of fun playing progressive rock after so many years.

‘Castles, Wings, Stories and Dreams’ was released with the participation of many musicians, lifelong friends such as Joe Vescovi (The Trip) Mauro Pagani (PFM) Ricky Belloni, Marco Zoccheddu and Giorgio Usai and many others. Then followed ‘Faces With No Traces’ with the participation of my son Alessandro and Leeroy Thornill (Prodigy) and the last of the trilogy in 2019 ‘The Leprechaun’s Pot Of Gold’. During the terrible pandemic which here in Italy was very heavy, I didn’t managed to touch an instrument: I don’t know, there wasn’t a precise reason but all those dead people squeezed my soul and I couldn’t even think of putting down a chord so I dedicated myself to inventing collages made on skins of drum (I made a hundred).

Now for about a year and a half I have resumed writing instrumental songs as well as doing some live shows around Italy. I went back to studying, this time orchestration and put together more than an hour of soundtracks for films that were never shot. I like it a lot, I’m 73 and music still fills my days in my home studio. I don’t have any short-term projects and I don’t want to do them waiting for a spark to strike that leads me to find a reason to publish my music and/or offer it in public.

I can only say without fear of contradiction that the music we were making then was the result of continuous contamination but no one knew he was playing prog because this word came many years later.

Klemen Breznikar

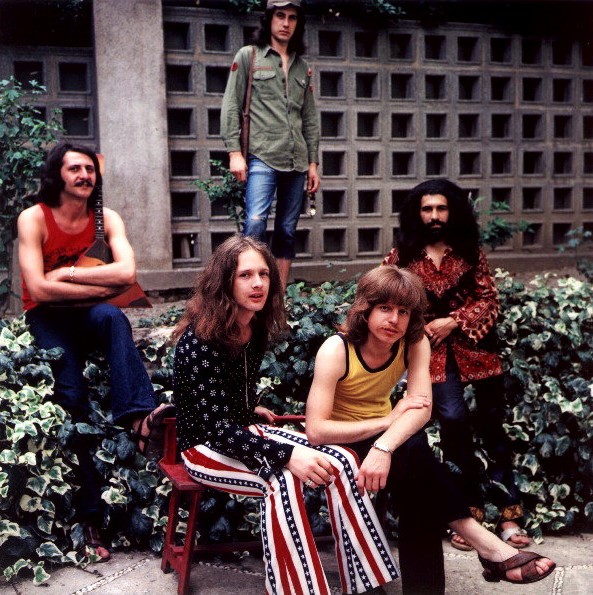

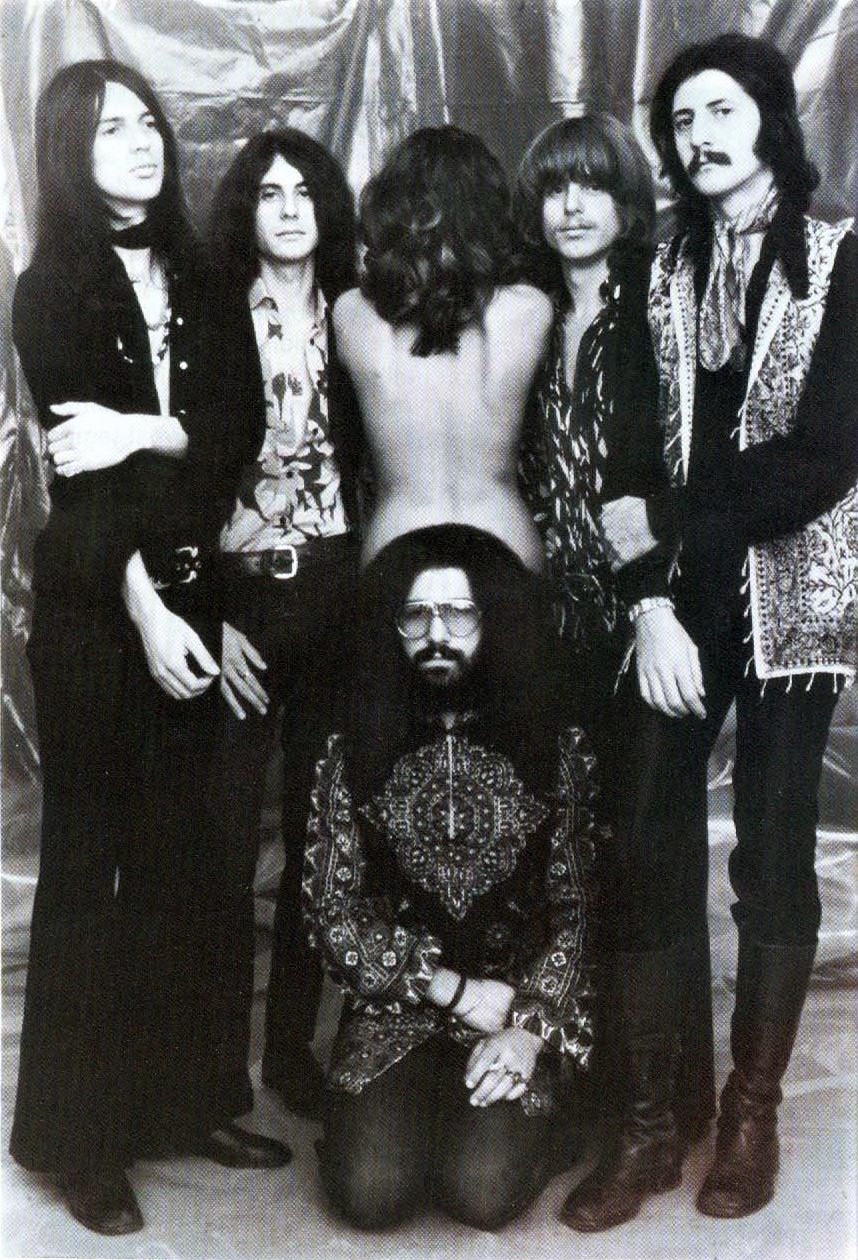

Headline photo: Nuova Idea (1973)