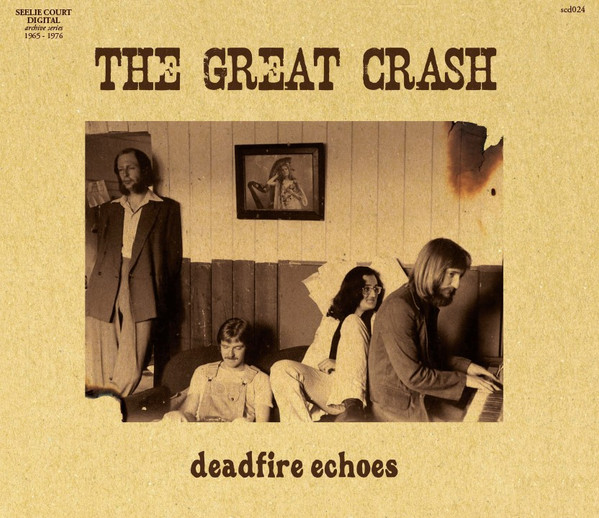

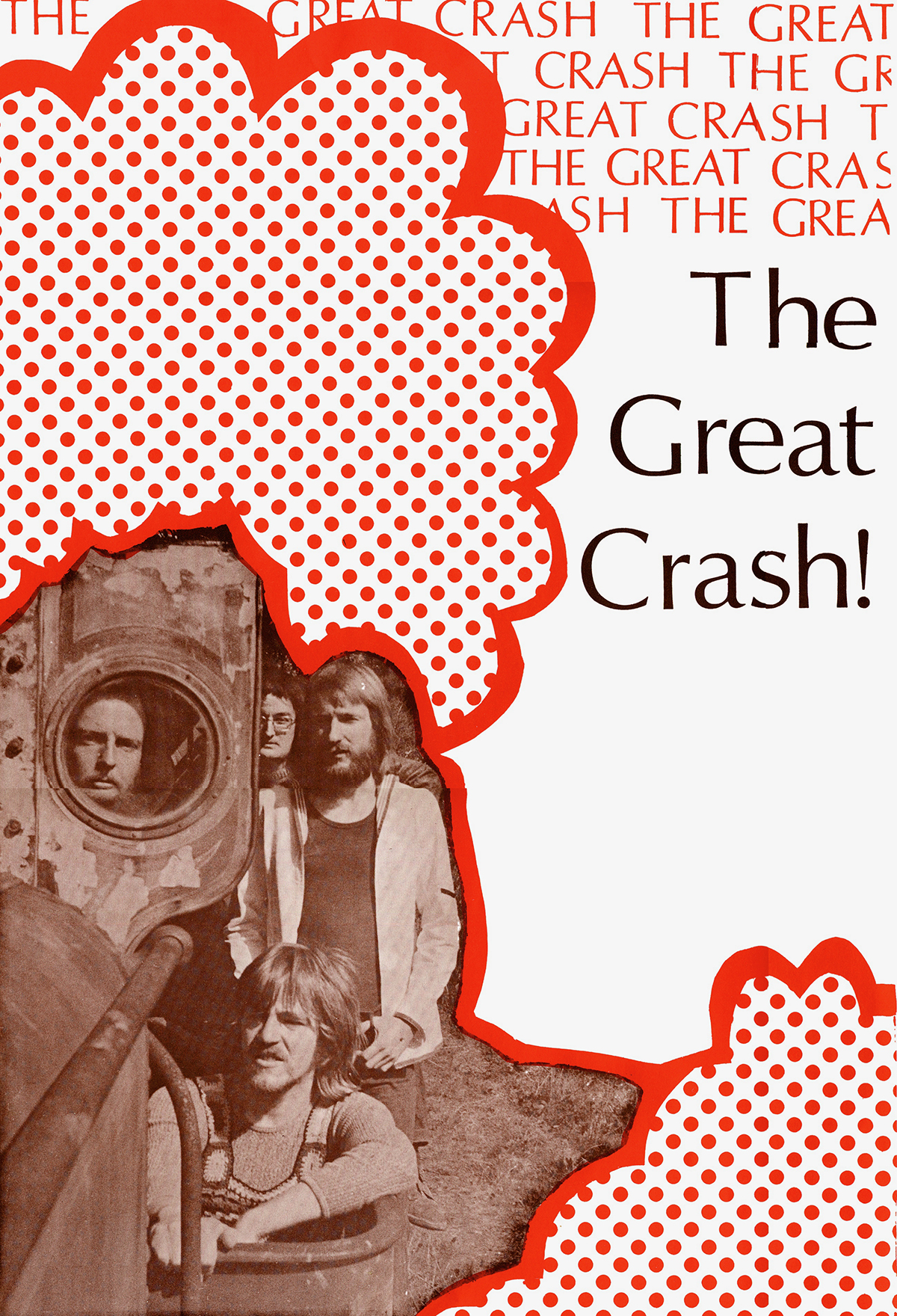

The Great Crash | Interview | Lost Recordings: ‘Deadfire Echoes’

The Great Crash recorded a genuine masterwork that sounds like a lost classic.

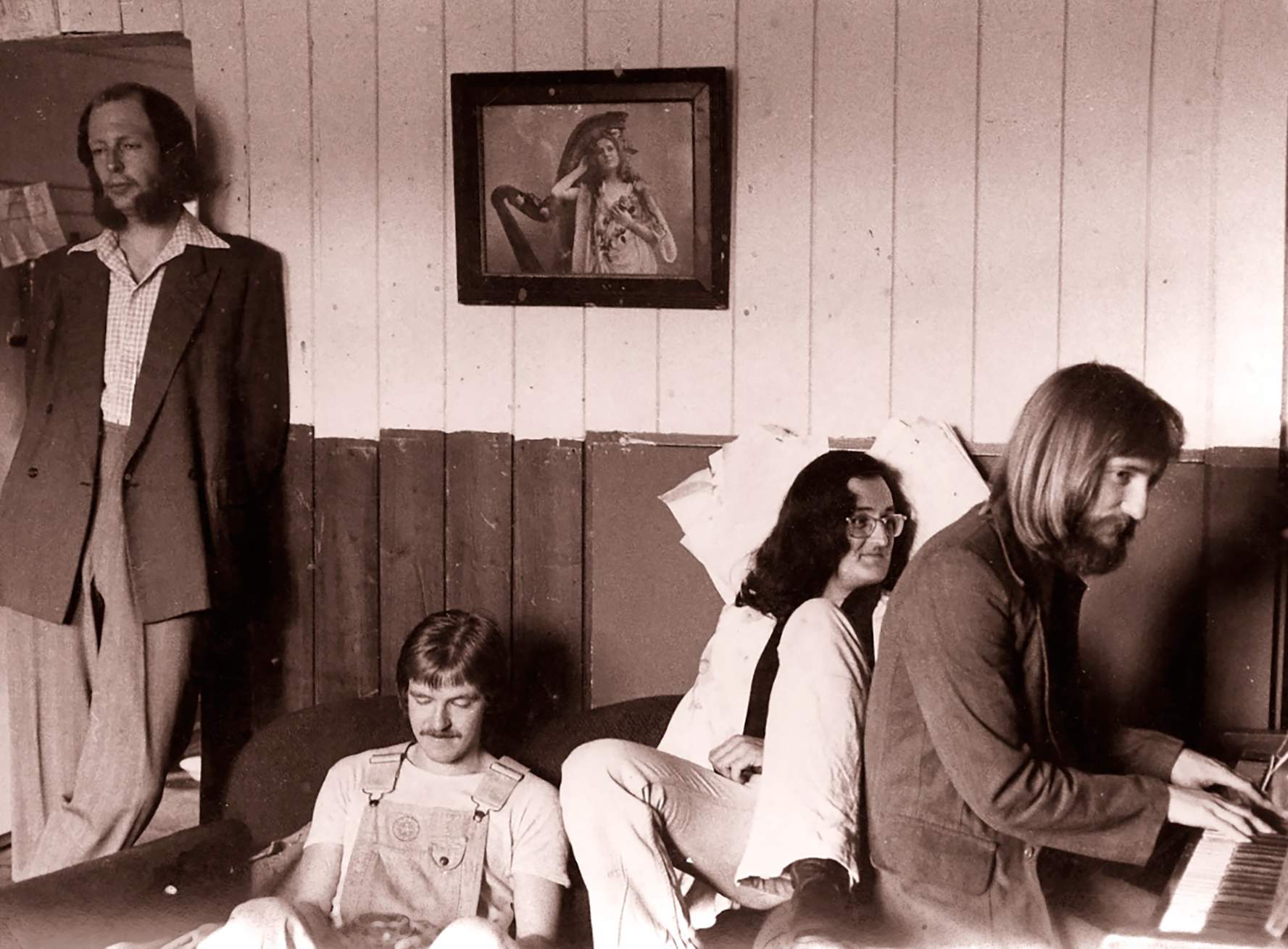

‘Deadfire Echoes’ from The Great Crash includes exquisite songwriting with piano led art rock that conjures the best of early melancholic Elton John and 10CC, recorded in an abandoned mansion in Wales. When The Great Crash gradually left their Mansion after three years there, it became Loco Studios, where the ghosts of the Great Crash’s songs swirled unknown around The Verve and Oasis as they recorded their 90’s masterpieces.

Thanks to Seelie Court who issued this fantastic release of ‘Deadfire Echoes’ and for making this interview possible.

“The songs are a selection of the demos that we recorded 1972 -1975”

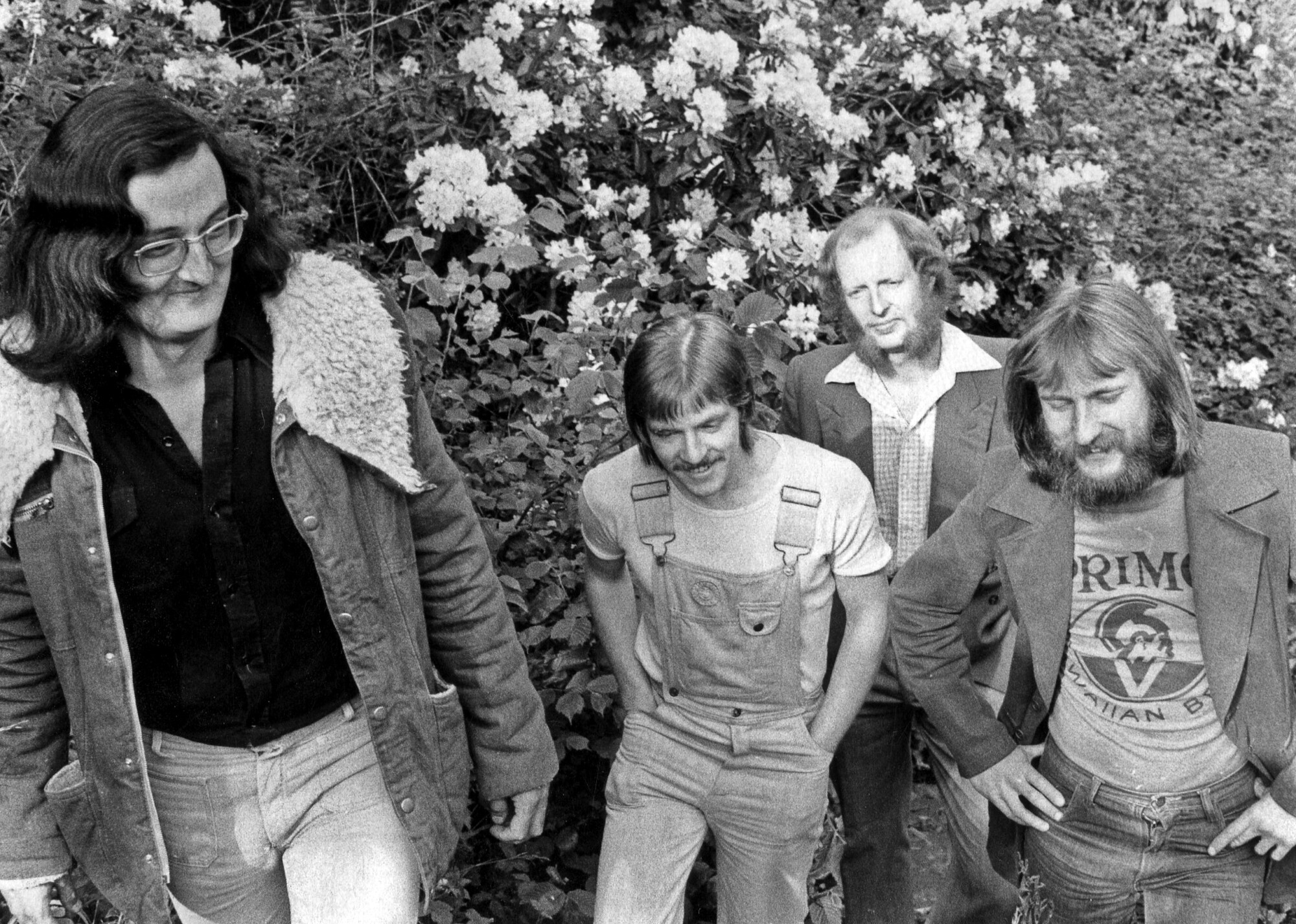

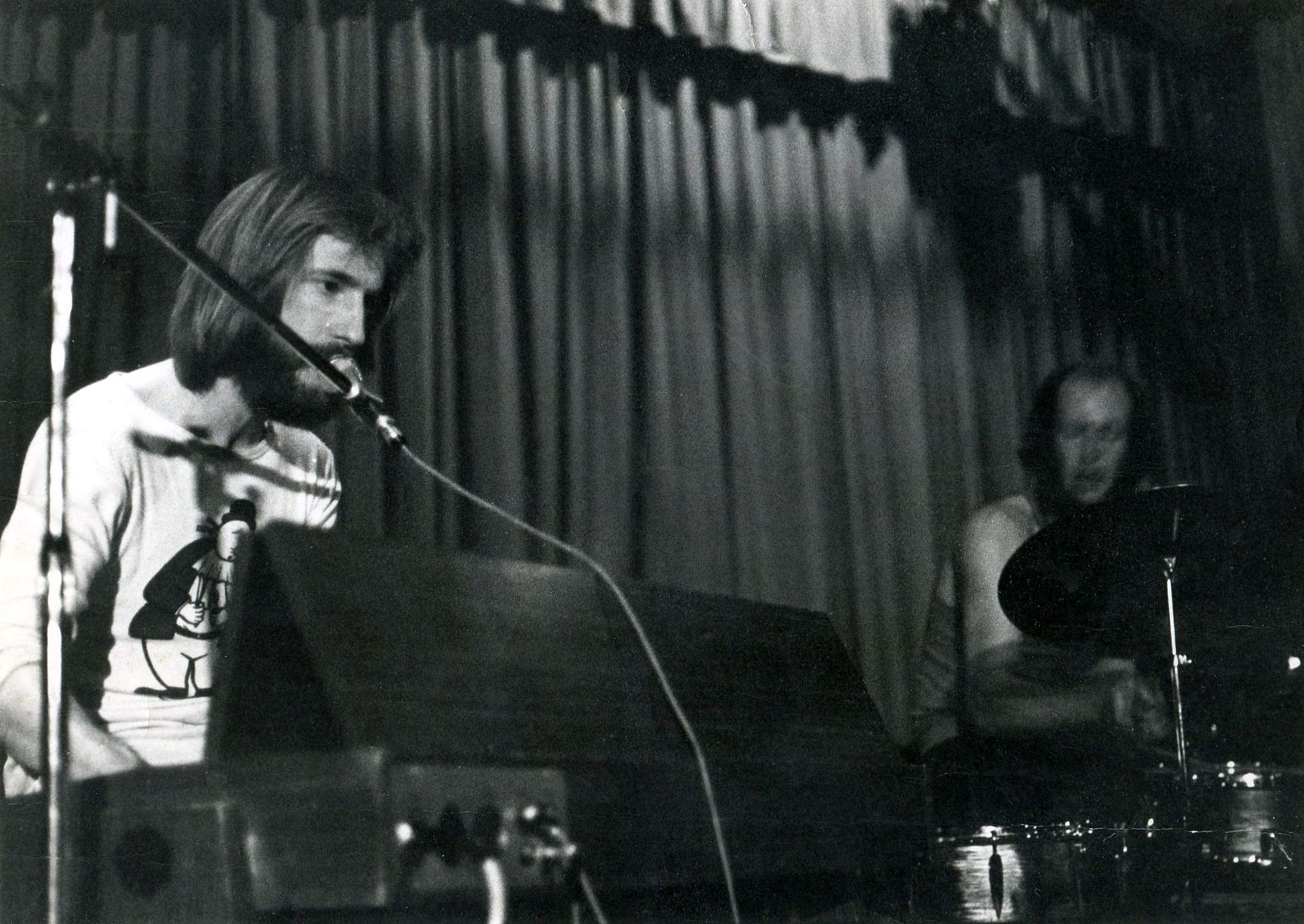

[Sadly we have heard that Piers Geddes, the Great Crash’s drummer and lyricist of many of the band’s songs, died shortly after he wrote his contributions to this interview. Piers’ bandmates – Al, George and Nick – wrote this about him: “We’ve been so lucky to have this chance to revisit the work we did together back in the 70s. As well as being an original, creative and often quirky lyricist, Piers was also a mighty fine drummer. Just listen, for example, to Celebration Dinner and the intricate patterns that both guide and echo the structure of the song. “Two of us, Al and Nick, had lunch with Piers recently to discuss Klemen’s piece and it will be good to remember him as he was then – funny, sharp as a whip, a great host – and a fine cook. We have lost a very dear and valued friend.”]

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

Al Gray: Born 1949, I grew up near Brighton, South of England. Aged seven, I had 78rpm records of Elvis Presley’s ‘Hound Dog’ and Jerry Lee Lewis’s ‘Great Balls of Fire’. I loved the records but couldn’t understand how the sounds were made. For example, I could only think that the guitar solo on ‘Hound Dog’ was made by someone throwing plates around and smashing them. I was a simple child! Although I was keen on pop music of all sorts, in my early teens I realised there was an alternative to saccharine, meaningless Pat Boone, Cliff Richard-style music when I discovered American country blues – singer/guitarists like Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, Leadbelly, et cetera. They were singing about real things, real life. From there, I got into electric blues, R&B, Chicago artists like Muddy Waters, rather like many other British youngsters who (unlike myself!) would eventually become big names in the British blues and rock scene.

George Benn: I was born in Burnley, Lancashire. When I was 9 we moved away and eventually settled in a small village in North Devon called Chittlehampton. There was no music tradition in my family but both my brother and I were able to buy cheap guitars – my first hero was Hank Marvin of the Shadows, which I think is true for many people my age. The only local music was to be found at the village dance on Saturday nights. And we all listened to the radio, but the Light Programme wasn’t famous for its rock’n’roll coverage.

Nick Smith: Born 1947 in Sussex – moved to London soon afterwards. Parents not musical but my grandmother almost became a concert pianist and put me on the music road. Started playing guitar at school as a way of avoiding some of the less pleasant aspects of life in the brutal British public school system. Like George, Hank Marvin was an early hero. My piano tuition had also been making fair progress until I was given an ultimatum by the head of music to choose between the group (The Insomniacs) or a future as a proper musician. No contest, of course, and I’ve been faking it ever since.

Piers Geddes: London born in 1950. There wasn’t much music in a rather empty family life. The BBC Light Program as it then was, Radio Luxembourg and English hymns were added to at home by some Schubert or Brahms – that was about it.

When did you start playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

Al Gray: At this time in the UK, pop music, beards, and “long hair” (hair to the top of the ear!) were considered by the establishment as a serious threat to society. So naturally we all did our best to grow as hairy as possible.

My father was becoming worried.

My mother was musical, and so, more sympathetic, resulting in the purchase of an acoustic Rosetti f-hole guitar which I immediately rigged out with a pick up and a Stentor 10 watt amp. At school, I formed a band called “The Gravediggers” (we were awful!) and a 3 piece country blues outfit called “Meat and two Veg” (not quite so awful).

Dad was seriously worried now.

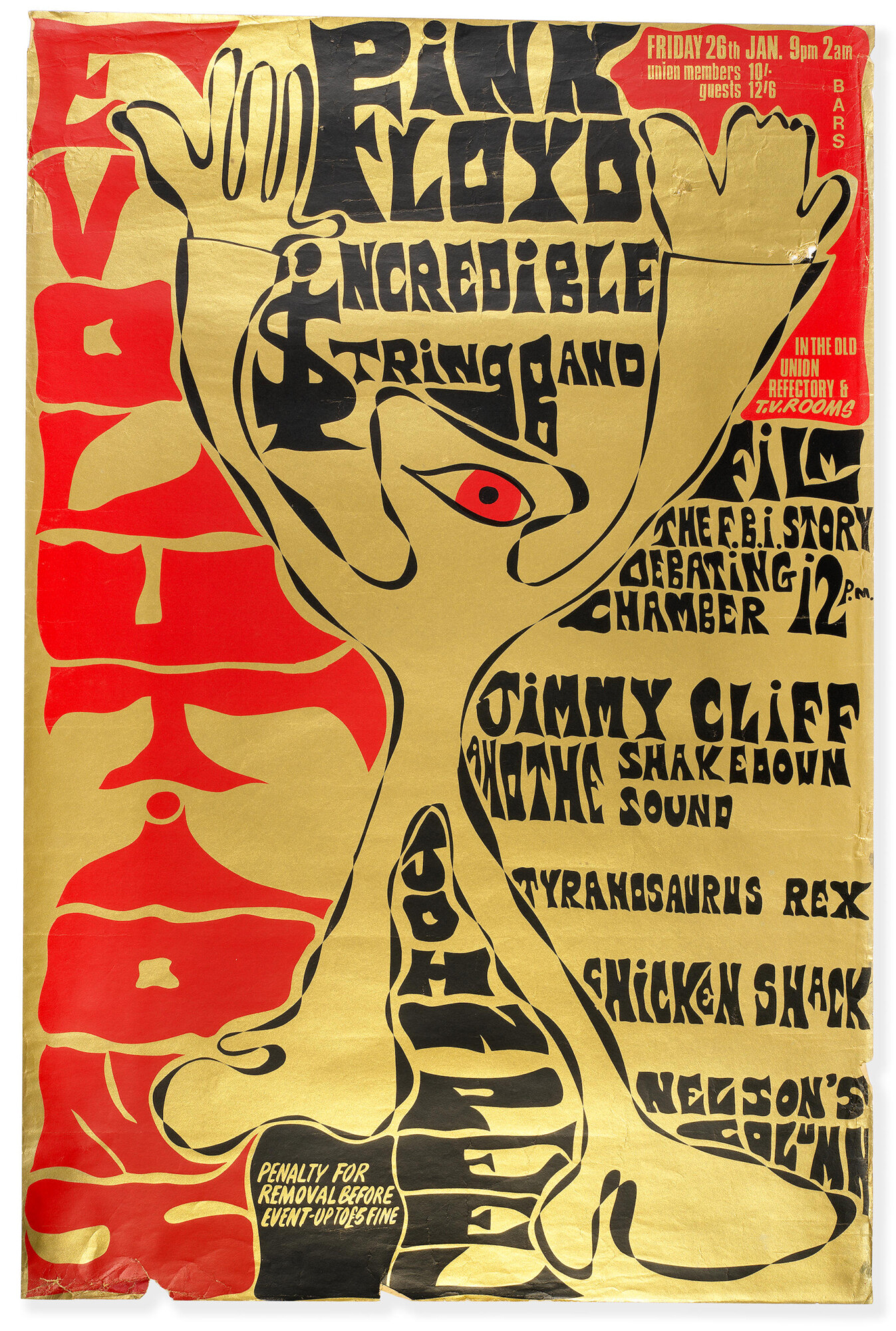

The first band I saw was probably “Count Downe and the Zeros” who played at half-time during the Brighton and Hove Football Club home games – the local club that me and my mate Johnnie followed. We were about 13 years old and even we could see they weren’t especially good. In my teens I was lucky enough to see Zoot Money, The Pretty Things, The Nice, The Artwoods, Gary Farr and the T-Bones, Alan Price, The Who, Yardbirds and The Moody Blues at various London Clubs; one of Cream’s first gigs, in Worthing; and Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix and Amen Corner on a tour in Brighton. And while later attending Southampton University, Cream again, Juicy Lucy, Traffic, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Chicken Shack and others.

George Benn: I began by getting hold of a cheap solid electric guitar (can’t remember the name) and trying to play Shadows tunes. This would have been in 1961 when I was 15. I had some friends at school who were into music and eventually the idea of forming a band was suggested. I bought an Elpico (I think) amp – pale green and about the size of a transistor radio – and was able to hear my feeble attempts at playing at a titanic 5 watts of volume. Eventually it was decided that as I was by far the worst of the potential guitarists I should play bass. I bought a solid Hofner bass that was quite good for its time. Subsequently it was traded in for a brand new 1964 Hofner Violin Bass which cost the princely sum of £54 (a living wage in those days was £10-£11 a week so it wasn’t cheap). When I went off to university I decided I wouldn’t need it and sold it. On my first day at Southampton University I walked into the Student Union building and heard a band practising! Selling that bass probably ranks with deciding to hold the Brexit referendum in the annals of totally stupid decisions.

Nick Smith: I also started with inept attempts to emulate The Shadows, Bert Weedon, the Ventures, Duane Eddy, Link Wray and other plank-spanking heroes of the early 60s. My first guitar was an almost unplayable acoustic, followed by the equally unrewarding but now iconic Futurama 3 (selected because of its many knobs and buttons from Bell’s – the guitar porn catalogue of its day) and then a gorgeous cherry red Hofner Verithin. This was bought at the cost of lasting damage to relations with my dad – the funds came from selling the set of golf clubs he’d given me for my 16th birthday.

When I got to university I found that being in a band continued to create a more interesting social life. That, rather than a real love for any particular kind of music, was the main motive until I discovered the Americana of Dylan, The Band, Buffalo Springfield et cetera and soul music from Stax, Motown and other more obscure US labels. Didn’t have a lot of time for bands from this side of the Atlantic apart from our live favourites – Cream, The Nice, Clouds, Eyes of Blue, Family, and of course Procol Harum, who were a big influence on the Great Crash’s writing.

There was a split between people who influenced my playing (e.g. Ry Cooder, Stephen Stills, Steve Cropper, Neil Young, J.J. Cale, Robin Trower) and guitarists who I loved but inhabited a different and unobtainable universe (e.g. Jeff Beck, Jeff Skunk Baxter, Larry Carlton, Albert Lee, Duane Allman).

Piers Geddes: It wasn’t music but at school several of us built so-called guitars out of cigar boxes with rubber bands for strings, held in place by drawing pins. Very rock ‘n’ roll! My first drum kit was a beaten up second-hand Gigster set costing £20 and covered in yellow Fablon.

I used to bash away in the attic, early Beatles records. Influence or not I can’t say, but legions of brilliant jazz drummers back then Buddy Rich blew me away, those one-handed drum rolls… And later, Keith Moon, so creative. No one ever played like him.

Were you members of any bands in the 60s?

Al Gray: I had by now discovered marijuana. One of its benefits is increased sensitivity, for example, to sounds. So, whereas as a child I thought I was hearing plates smashing during the ‘Hound Dog’ guitar solo, now I could hear and identify instruments and parts during a song rather than just a lump of sound.

Father had lost his hair.

Apart from the aforementioned school bands, I played with Nick, George and Piers at University (more on that later).

By now, I’d started writing songs with Piers Geddes and having met engineer Damon Lyon-Shaw, we recorded some demos at IBC studios, London, including some with Nick and George who we’d played with in Southampton as Springheel Jack. They sounded pretty good and we were encouraged to take it further.

Piers Geddes: At school I was drummer in The Blue Diamonds, which expanded into The Hellfire Club with the addition of a sax player. Clearly we were embedded in the local music scene when Twinkle (ephemeral UK 60s pop star) performed her set sitting on my drum stool! Then at university I met Al and played on his great work Bertie. Later we teamed up with Nick and George to form Springheel Jack. I did percussion and a few harmonies but most of the time I played a Yamaha acoustic – I never mastered it!

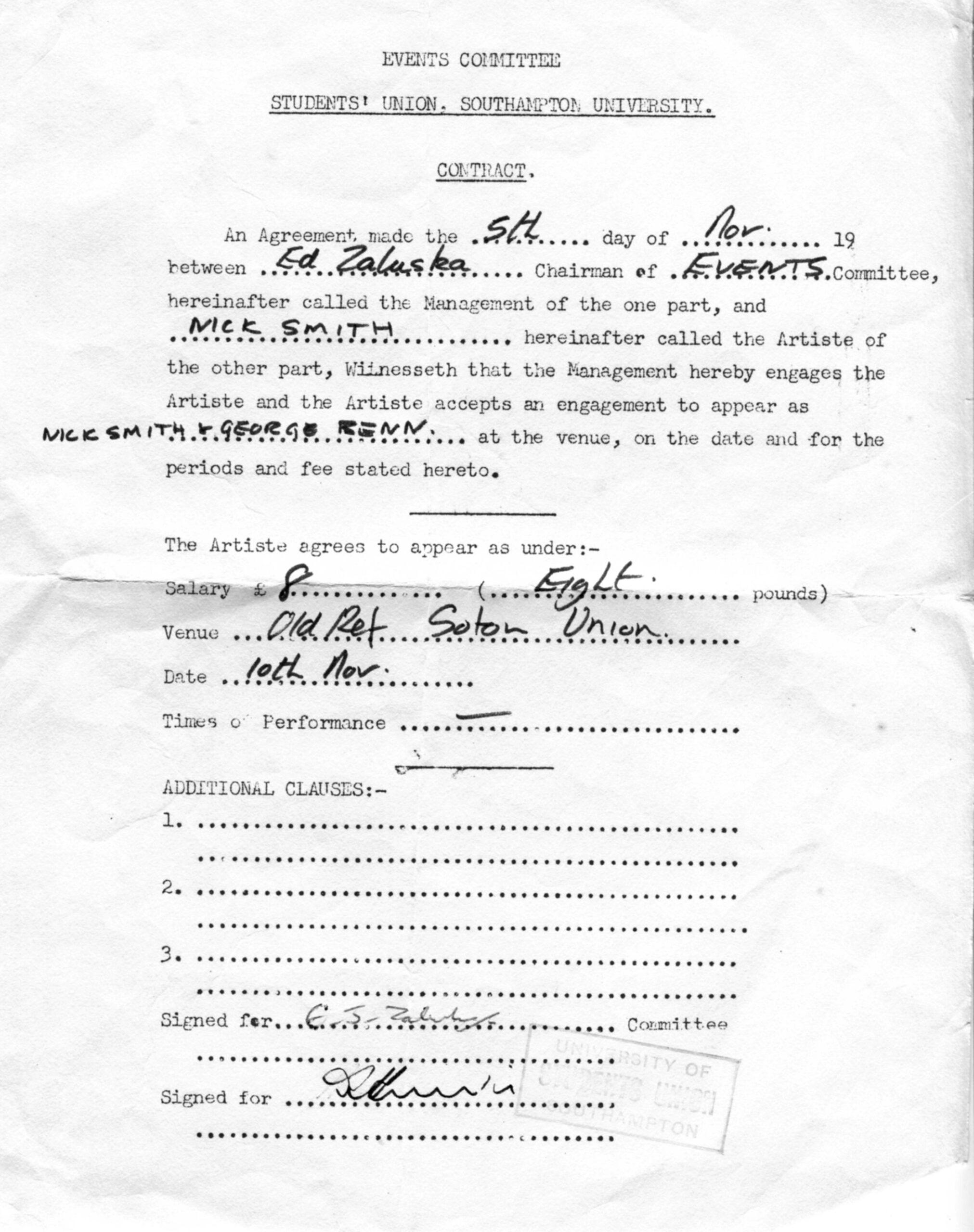

Nick Smith: George and I were in a couple of bands when we were both students at Southampton University. The main one was Nelson’s Column – George was the singer and I played bass. We supported many famous bands and shared the stage with, amongst others: Pink Floyd, Fleetwood Mac, Cream, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Taste, The Nice, Family, Chicken Shack, T. Rex, John Peel. The only significant interaction I can remember from these gigs was asking Eric Clapton if I could move his guitar and him telling me to fuck off. There’s a poster for one of the gigs NC played (Evolution).

After university, while George and I were trying to get things going with the Benn-Smith duo, I worked as a roadie for a couple of south coast bands – the Nite People and the Mojos. I played an uncredited acoustic guitar on the Nite People’s album ‘P.M.’ (produced by Phil Waller of the legendary Troggs’ tape fame) and spent some time playing and writing a few songs with The Mojos’ Stu James.

George Benn: I was in a band that we formed at school called The Sidetracks. We weren’t that good but luckily for us The Beatles came along at just the same time so we learned some of their songs and became very popular in North Devon. When I went to university in Southampton in 1965 I was in a band called The Splinter Group for a year, then Nick and I were in Nelson’s Column for two years. As for after dinner stories, I tell the one about how we once shared a dressing room at Connaught Hall of Residence with The Yardbirds, and Jimmy Page showed Chris, our guitarist, his method of playing guitar with a violin bow. We also did several gigs with a band called Clouds (formerly 1-2-3) who were great musicians and would always allow us to use their new Vox amps. Best of all, when I was with The Splinter Group we went to Reading Uni to support a band called Episode Six. They did brilliant surfing music. Three years later they were Deep Purple!

After graduation the band broke up and that was when Nick and I became a duo.

Nick Smith (guitar) and George Benn (vocals, guitar) formed an acoustic duo in Southampton playing all original songs. Can you tell us what songs you play? Are there any recordings left? There was some interest from record labels?

Nick Smith: We wrote lots of material and recorded demos in my bedroom, using track-to-track bouncing on a stereo tape recorder – the method we later used for all The Great Crash recordings. Sadly all the recordings are lost – titles I can remember are ’Ninevah Farm,’ ’My Magic Garden,’ ’The Ballad of Springheel Jack,’ ’Attack by Sea’. Generally George the words and I wrote the music, although George did write both words and music on some later songs.

There was interest from record companies and publishers – but never quite enough to generate that elusive contract. We did one gig as a largely terrified duo – supporting Martin Carthy in front of a packed student audience who seemed to love it.

George Benn: We wrote and recorded quite a few songs but sadly the tapes were lost long ago. I have a book of lyrics somewhere (where?) with most of our songs in but I don’t suppose I could remember how the melodies went. There are two songs from that time which I do remember and sometimes play (I go out solo to folk clubs and open mic nights), one called ‘Sparrow’ and one called ‘Water and Wine’ (there is still a recording of ‘Water and Wine’ that we made at the time. I recorded both those songs a few years ago for my first solo CD).

What are some clubs you played? Who did you share stages with?

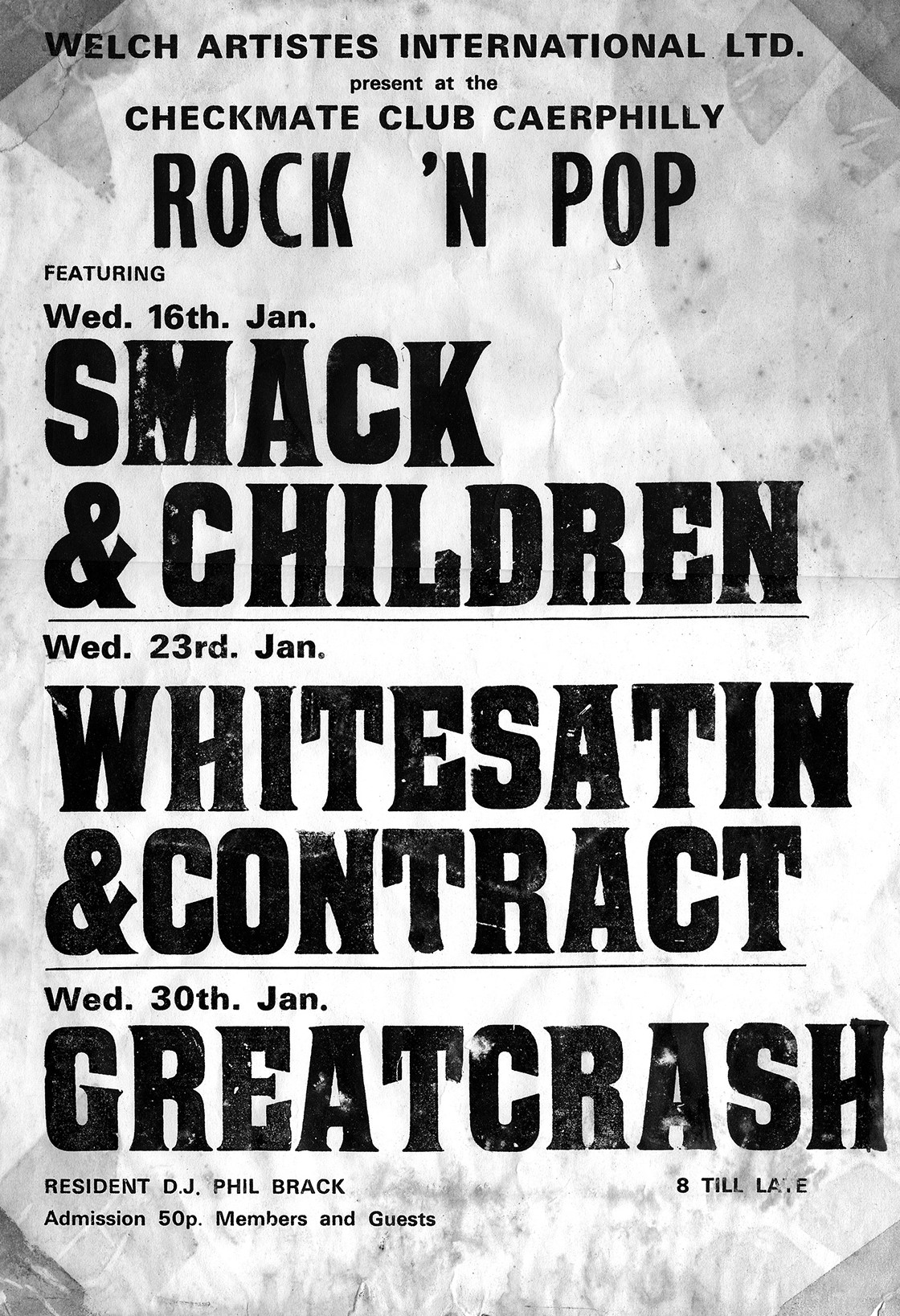

Al Gray: Prior to the formation of The Great Crash, none worthy of mention. After that, mainly clubs in South Wales such as Gassy Jacks, Cardiff and TJ’s, Newport, Llanelli Ballroom as well as a few further afield such as the Cavern Liverpool, Music Box Weymouth, the Granary Bristol and Cosmo’s St Andrews.

George Benn: Nick and I did a few gigs around the University. Springheel Jack did a few gigs as well. The only notable name I remember from those times is Tír na nÓg. I think that was a Springheel Jack gig.

What led you, Al Gray, to work on a rock opera called Bertie? Tell us who all was behind the project and where did you record it?

Al Gray: In 1969, The Who released the pop opera ‘Tommy’. I thought it was bollocks. So, with a few friends, I recorded my own spoof pop opera called ‘Bertie,’ in my bedroom in Southampton. We’d never recorded any music before so really had little idea what we were doing. It shows. We recorded it on a stereo reel-to-reel tape recorder, building up tracks using the “ping pong” method. Unfortunately, owing to our inexperience, we didn’t realise that drums should be laid down first (rather than last!) and the result is a trifle disjointed – fine if you’re Captain Beefheart, otherwise a bit of a no-no. We made 50 copies on vinyl and sent one to renowned DJ John Peel. He was kind.

Bertie LP’s were handmade each with unique covers, and a copy was sent to John Peel who replied back…

Al Gray: His verdict was that he liked the idea although the execution of it wasn’t quite so good.

Tell us what was the concept behind it? And what influenced you to write the songs?

Al Gray: A typical ”everyman” story of someone searching for some meaning in his life, something more than the hum-drum repetitive daily grind. He tries Eastern philosophy, sex, drugs and political protest before accepting his fate. I would add that it’s not entirely serious.

How come you decided on unique covers?

Al Gray: We were students with no money so choices were confined to the most basic method. We bought some shiny white cardboard, cut it to size, and sprayed lettering in red or blue using a template.

Where was the album pressed and how many copies were pressed?

Al Gray: We pressed 50 copies and sold them all for £1 each, covering our outlay. Can’t remember the pressing plant, but the receipt is printed on the subsequent 2022 release.

How did the Springheel Jack come about?

Nick Smith: George and I vaguely knew Al and Piers, who we thought of as being slightly eccentric and dangerously creative. They existed in a far more avant garde environment than George and I, as evidenced by the Bertie album. However, they did not, unlike Benn-Smith, ever run the risk of appearing in public.

George Benn: I have no idea how the Springheel Jack thing came about. By then I was working in Reading and commuting back to Southampton at weekends to write with Nick. I don’t think any of us thought logically about anything we did at the time. Joining forces with Al and Piers would have given us a bigger sound and perhaps more gigs was probably the extent of our thought processes.

Nick Smith: Ah – I’d forgotten about George’s lucky escape from a lifetime working for the Gas Board! But now I remember Bob Benn – George’s dad, who used to visit us fairly regularly in our rural squalor at Plas Llecha – saying the only time he’d ever worried about George had been when he was stuck in that office in Reading.

I can’t remember either how Springheel Jack came into being. Maybe George and I were impressed by the fact that Piers was a drummer/percussionist and Al could play both piano and guitar, as well as having a great voice. But whatever the reasons, the result of the four of us getting together was an explosion of creative energy the likes of which had seldom been seen before in the UK rock firmament. Or, as an agent once said to our then-manager at a gig in South Wales: “…not bad for Tredunnock.”

Piers Geddes: The four of us deciding to play together – I can’t remember either, but at the time an acoustic band called America had a hit with ‘Horse with No Name,’ so that might have been a spur.

Did you record any of the material as an acoustic band?

Al Gray: As mentioned above, we recorded a few tracks at IBC studios, London with Damon Lyon-Shaw. They included ‘Precautions’ and ‘Attack by Sea’.

Nick Smith: Recording four people at the same time was well beyond the technical limitations of Smith bedroom studios in Southampton, so that lost IC acetate was all that was ever recorded by Springheel Jack.

If I understand correctly you decided to go electric and renamed the band to The Great Crash?

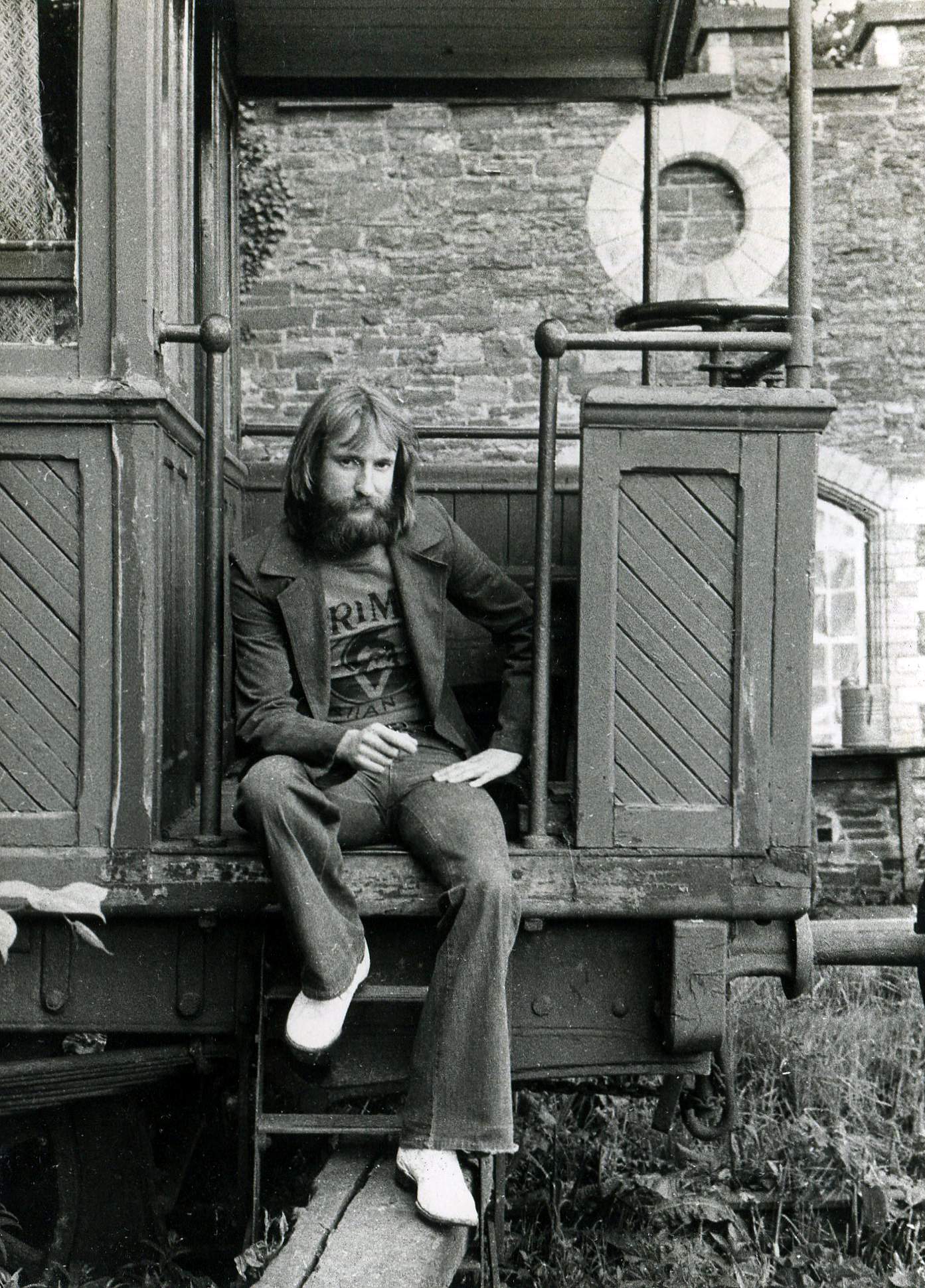

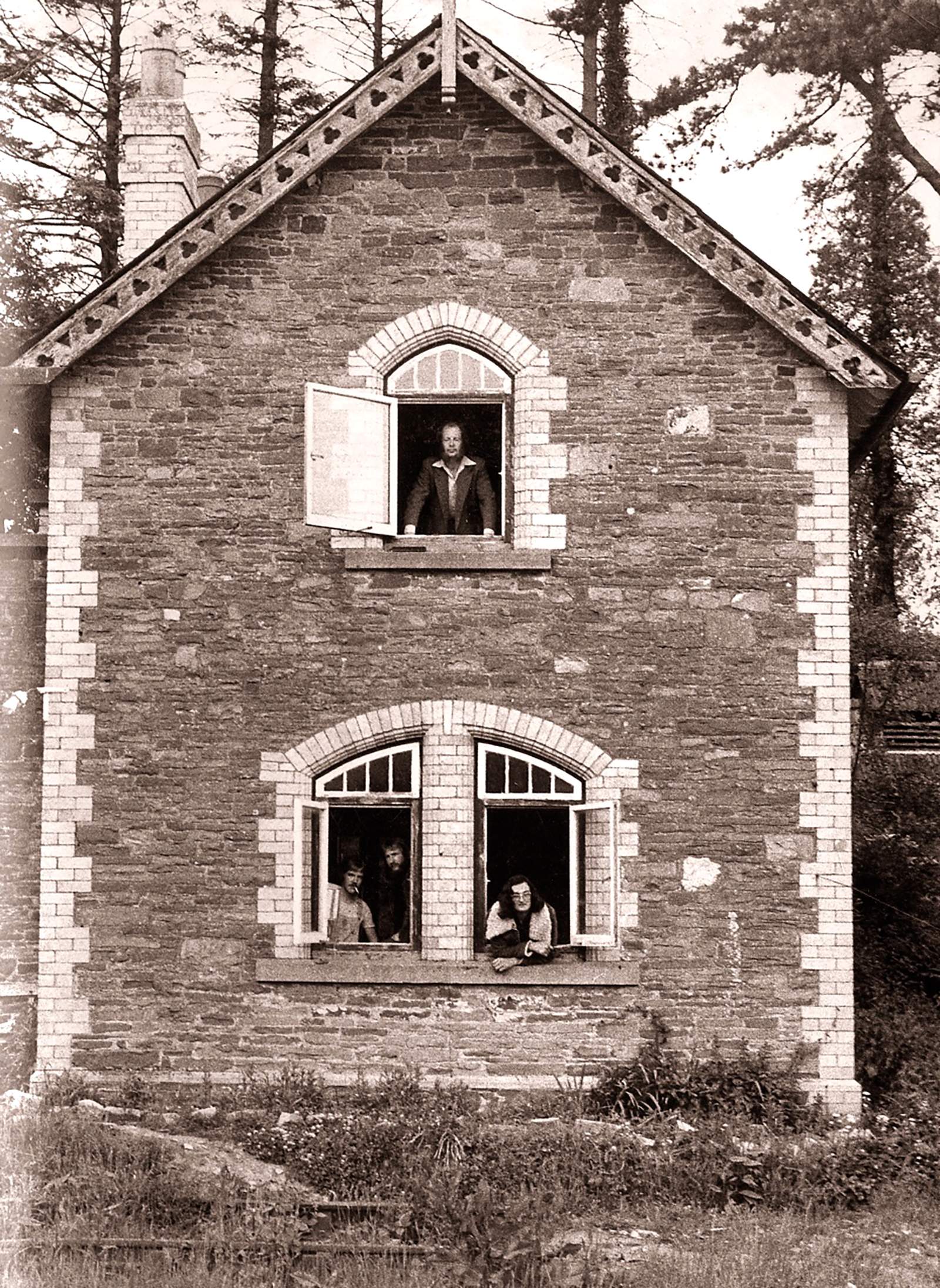

Nick Smith: Springheel Jack attracted the interest of a local entrepreneur who offered to put money into the band so that we could go electric and give up our day jobs. We used his cash to buy a van, a PA, amps and other bits of kit and headed off to Plas Llecha – a semi-derelict country mansion in Monmouthshire owned by a relative of Piers. The initial plan to leave Southampton for 2 weeks to “get it together in the country” eventually turned into a permanent migration for the 3 Great Crash members who are still living in South Wales.

Before we left Southampton we’d decided to expand the band by adding a drummer (because Piers wanted to be free to play other instruments) and a lead guitarist (because my experience had been mainly as an acoustic guitarist). But the new members – who none of us knew very well – weren’t at all happy with the Great Crash approach and left after about a week. So a major challenge for Piers and I when we decided to continue as an electric 4-piece after the hired hands left was adapting to these new roles.

Al Gray: Having been encouraged by the quality of our demos and subsequent interest from among others, Shel Talmy for whom we auditioned, we thought we should acquire electric instruments and do the job ”properly.”

George Benn: I was out of the loop when the decision to go electric was made – I was touring around France on a motorbike with my then girlfriend. Having at last managed to become vaguely competent on guitar I returned to Blighty to find myself a bass player again!

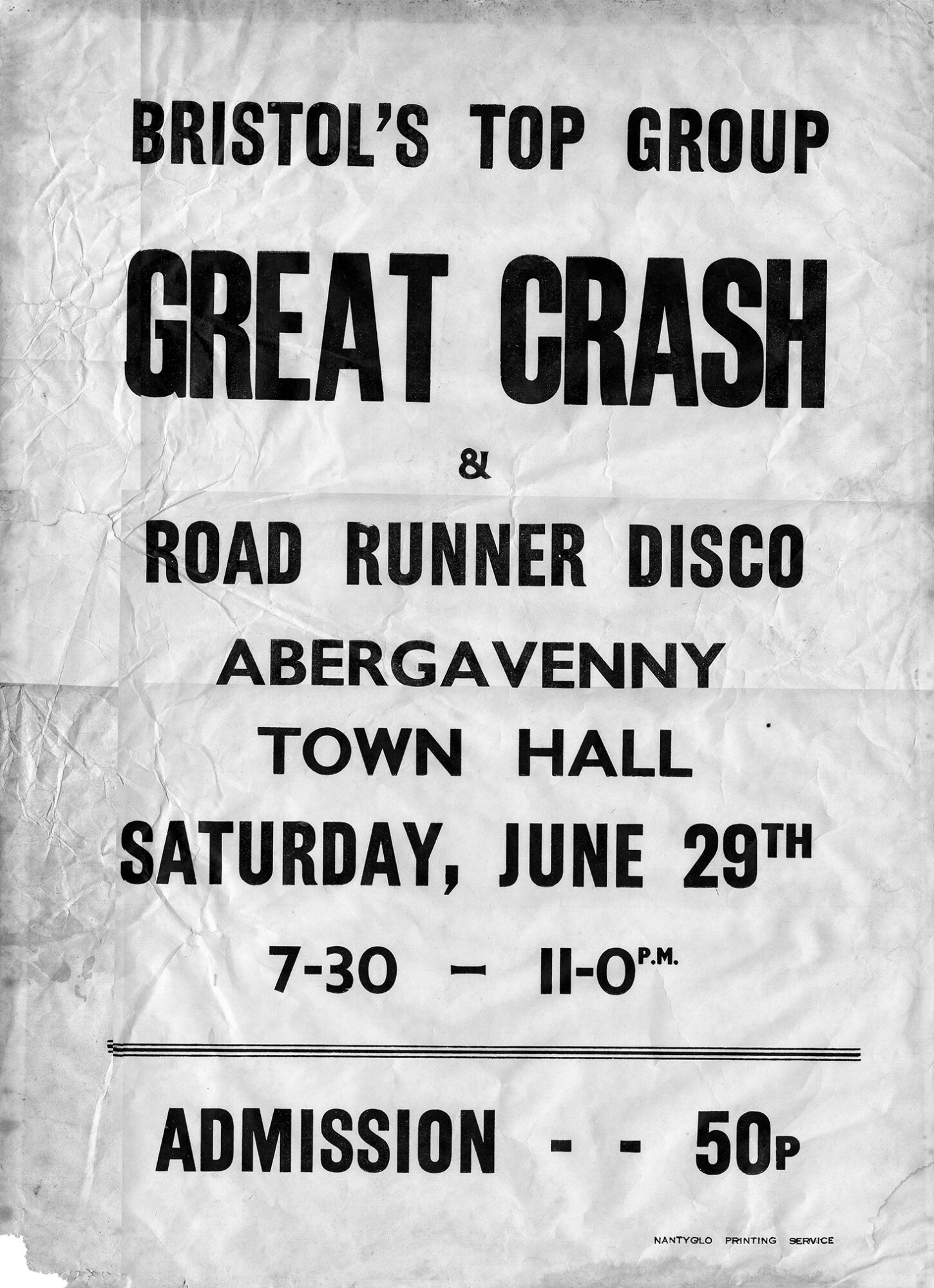

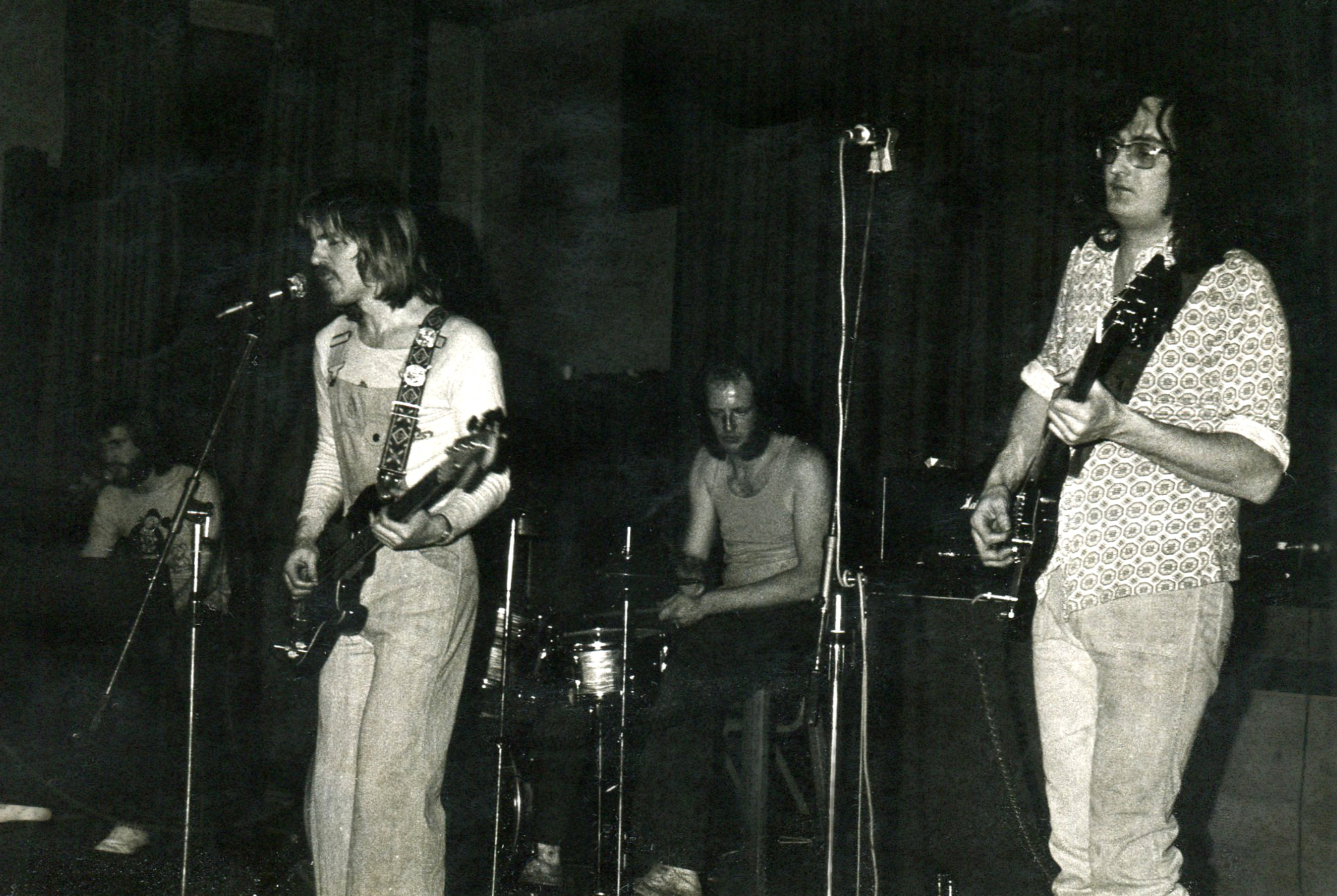

When and where did The Great Crash play their first gig? Do you remember the first song the band played? How was the band accepted by the audience?

Nick Smith: The first Great Crash gig was at the Kensington Club in Newport – I think it was about 2 or 3 months after we’d moved to Wales in the summer of 1972. We weren’t great live performers at that time and were extremely nervous. Audience reaction to our set of original material was at best lukewarm. Later we realised we would have to include covers to avoid violence at the hands of the audience and we started trudging up and down the country in our battered, unheated Transit paying our dues in a number of small and now largely forgotten venues.

I don’t think we ever became inspired performers, but playing regular live gigs did a lot to make the band tight and helped us become more accomplished musicians.

Al Gray: Yes, thinking that once Joe Public heard the first note of the first bar of the first song of our first set, we would be catapulted to worldwide stardom, we were stunned by their totally apathetic reaction. The next morning I resolved to escape the compound, reach the Swiss border, find a safe house and make my way to Blighty and safety. I was soon tracked down and bundled into a car. In the depths of despair, I realised the dark fate that awaited me – namely another two years strapped to a piano.

Piers Geddes: I’ve forgotten the rest of the song, but the lyrics to the opening number of that first gig began “We set our course, said our goodbyes, Brushing smoke and dust from our eyes” – or something like that. Nick’s right – we weren’t that great live to start with, but remember we were two pairs of songwriters first and foremost, which was both our strength and our weakness.

What sort of venues did The Great Crash play early on? Where were they located?

Al Gray: As already mentioned. All sorts of music venues, rugby clubs, social clubs, Con clubs, mostly in South Wales.

Nick Smith: We were reluctant performers to begin with and the venues were not the greatest – but the work did keep coming in. We got a lot of gigs through Bristol’s Pat Vincent Agency and we always took care to abide by the contract’s two key conditions: “…the band will wear appropriate stage clothing” and “…will play at a low volume.”

Piers Geddes: The “appropriate stage clothing” was ditched pretty quickly, but in some places ‘low volume’ was enforced by a cut-out switch which silenced the band if you played too loud.

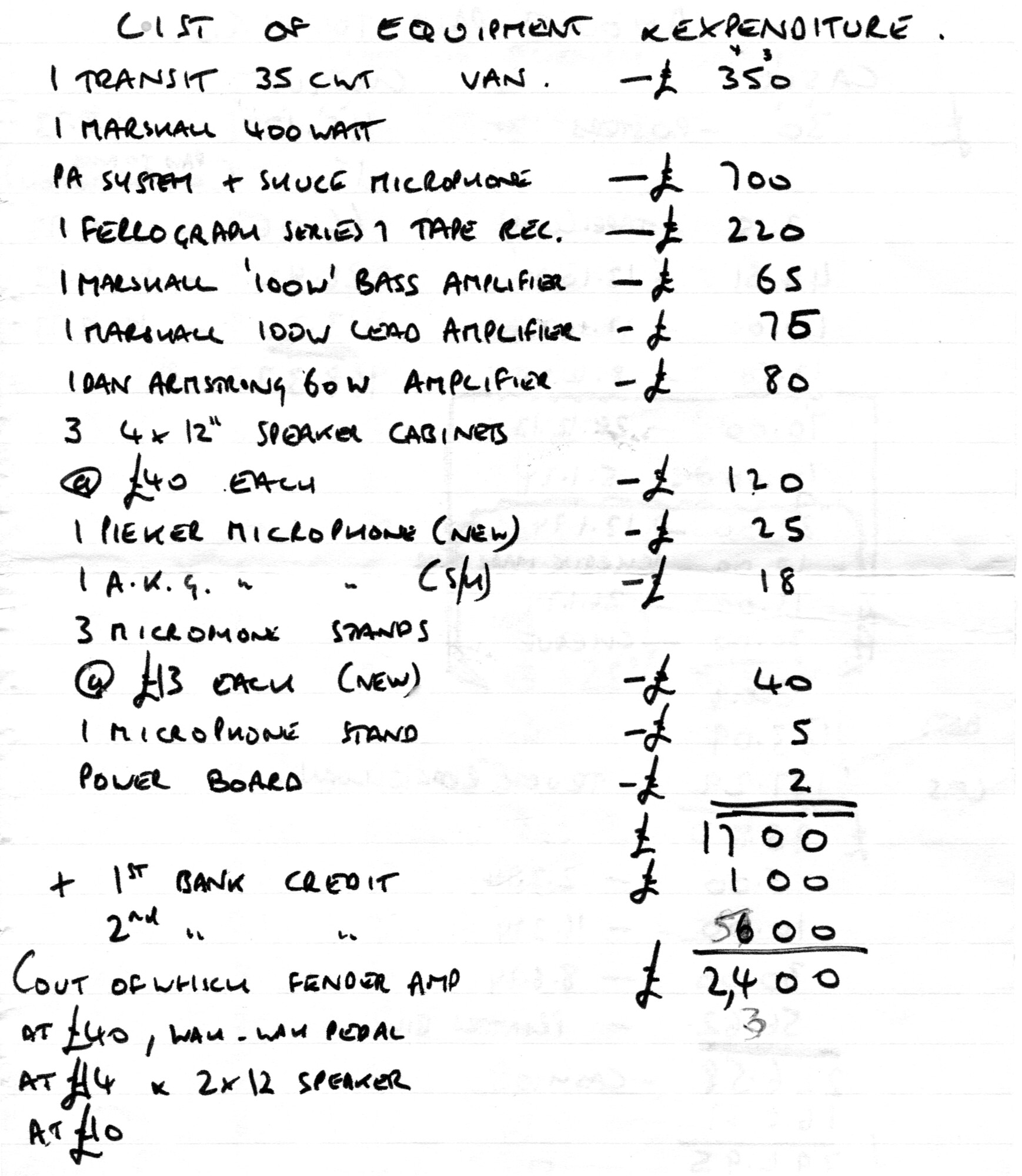

What kind of equipment did you have in the band?

Guitars: Gibson SG Junior, Guild S90, Jedson and Yamaha acoustics.

Fender Precision Bass

Hohner Pianet

Premier drums

Marshall, Fender and Danelectro amps

Mics: Shure SM57, SM58, Beyer

PA: Marshall valve 8 channel mixer, 4 x Marshall 100w power amps, 4 x Marshall PA cabs (1 x15 + horn)

Demos recorded on Ferrograph Series 8 recorder (¼”, running at 7.5 ips). Overdubs by bouncing track-to-track.

Shure spring reverb unit

George Benn: The Marshall PA was excellent but the speakers weighed a ton. The mixer enabled us to make our recordings so it was a good buy.

Nick Smith: We were occasionally double booked (i.e. the agent cocked it up and booked 2 bands for the same gig; one had to back down and slope off home unpaid) with a Cardiff band called Jackstraw (keyboard Graham Smart later became part of the Loco Studios jingles team). We both had the same PA and Jackstraw’s roadie would carry two Marshall PA cabs at a time – one on each shoulder – while in the Great Crash it took two feeble wimps to lift just one of the horrible grey boxes.

Tell us about ‘Deadfire Echoes’ recordings that Seelie Court released.

Nick Smith: Seelie Court told us that they wanted to give a consistent flow to the music in choosing the track order for the ‘Deadfire Echoes’. The CD was intended to give an idea of the four sides of the eventual vinyl release, where the art-rock ballads make up disc one, and the more country rock flavoured tracks disc two.

As far as the recordings themselves are concerned, the tapes had been sitting in a box in George’s house for many years until we had the idea in about 2003 of digitally salvaging the demos. George had the IT expertise to do the first pass of removing hiss, crackles and dropouts using software called Clean. Some of the tapes were so fragile that we could only risk playing them once or twice before the oxide started to fall off. Once they had been safely encoded and scrubbed up George sent them to me for mastering because of my background as a sound engineer at Loco in the 80s and 90s. I used a mixture of Pro Tools and Bias Peak, but tried not to stray too far from the feel and sonic range of the originals.

I think Seelie Court may have done some further minor remastering of the tracks for the CD, but the general sound and feel is unchanged.

Al Gray: The songs are a selection of the demos that we recorded 1972 -1975 on the above equipment at Plas Llecha where we all lived together. Nick was the engineer since he was the only one with the slightest notion of how it all worked. I believe Seelie Court are planning a vinyl release this year which will include some additional tracks as well as the songs on the ‘Deadfire Echoes’ CD.

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

Al Gray: Just ideas that popped into our feverish imaginations, often after a Benson and Hendrix and a few pints of home made Looney Brew.

George Benn: Hendrix?? See below for my thoughts on the Looney Brew. As Piers probably wrote more of our lyrics than anyone else he’s probably best qualified to discuss inspiration, but speaking personally the thing about songwriting is to take an idea from somewhere – a chance remark, a newspaper story, a TV show, whatever – and construct some sort of story or mental picture. Then you have to get someone to put it to music and this often bends the song in ways you didn’t expect. Witness the song ‘Witchfinder General’ which I’d envisaged as a sort of blues when I gave Nick the lyrics.

“Ideas came from the books I was reading, people I knew, interests I had”

Piers Geddes: Agree with what George (we were both lyric writers) says about inspiration, but for me it goes a little further and deeper. It was usually lyrics first, then handed over to Al, who wrote the music and did the arrangements. Ideas came from the books I was reading, people I knew, interests I had…

Nick Smith: Interesting to hear George’s recollection of ‘Witchfinder General’ – hope you weren’t too upset with how it turned out! I’m sure that’s correct but I generally have little memory of the writing process for the Benn-Smith songs. I remember the painstaking recording process quite clearly though. First, we would record the backing track live on the left of the two stereo tracks on the reel-to-reel Ferrograph recorder, usually without a guide vocal. Then we’d start to build up the vocals, backing vocals, solos and fills, percussion and any other overdubs by bouncing across to the other track – sometimes up to 4 or 5 times. Quite a scary process as the only thing you could keep was the immediately preceding bounce-down. And we had to mix as we went along. Sometimes l would spend all night on a guitar overdub – often to review it the next day and start all over again..

But one good thing about this way of working was that the arrangements were very carefully thought out – and no more complex than they needed to be.

Was there a certain concept behind the album?

Al Gray: None.

Nick Smith: Agree with that – definitely no overall theme or concept. In fact, it was sometimes said the band was a bit too eclectic – that the range of styles we encompassed made it hard for producers and record companies to know how to categorise us.

Were you inspired by psychoactive substances like LSD at the time of writing the album?

Nick Smith: Yes.

Al Gray: Yes.

George Benn: Particularly Al’s Home Brew. As we were far too poor to buy drinks even at Social Club prices Al used to make batches of beer to take with us to gigs. You could see into it sometimes, never through it. But it did the trick, fuelling the frenzied on stage antics that left audiences the length and breadth of South Wales completely unmoved.

Piers Geddes: No – but I agree about the homebrew. Delicious but lethal.

How did you get involved again with John Peel?

Al Gray: As mentioned before, on completing ‘Bertie,’ I sent a copy to John Peel. On forming The Great Crash, we thought it might be worth contacting him and sending him some demos. He remembered ‘Bertie,’ liked the demos and booked us to play live on his show. After The Great Crash, I got a deal with Rockfield Studios and released two singles, both of which he played on his show.

What are some clubs you played? What are some bands that you shared stages with?

Al Gray: As aforementioned. Brett Marvin and the Thunderbolts (Jonah Louie). Deke Leonard’s Iceberg. Jack Straw.

George Benn: Mostly we didn’t share stages with anyone, we would be the evening’s entertainment at whatever Miners Club or Social Club we were at. I remember that we were always, it seemed, appearing a week before or a week after the Searchers.

Piers Geddes: And don’t forget that place in Pembrokeshire run by a little man with a great Dane almost as big as him.

Nick Smith: Yes – not a lot of glamorous venues or stage sharing with The Great Crash – certainly in comparison with the illustrious names that our student band Nelson’s Column had supported. But I do remember Quaintways in Chester with Wilko Johnson and The Glen Ballroom Llanelli with Deke Leonard’s (previously with Man) Iceberg.

What would be the craziest gig you recall?

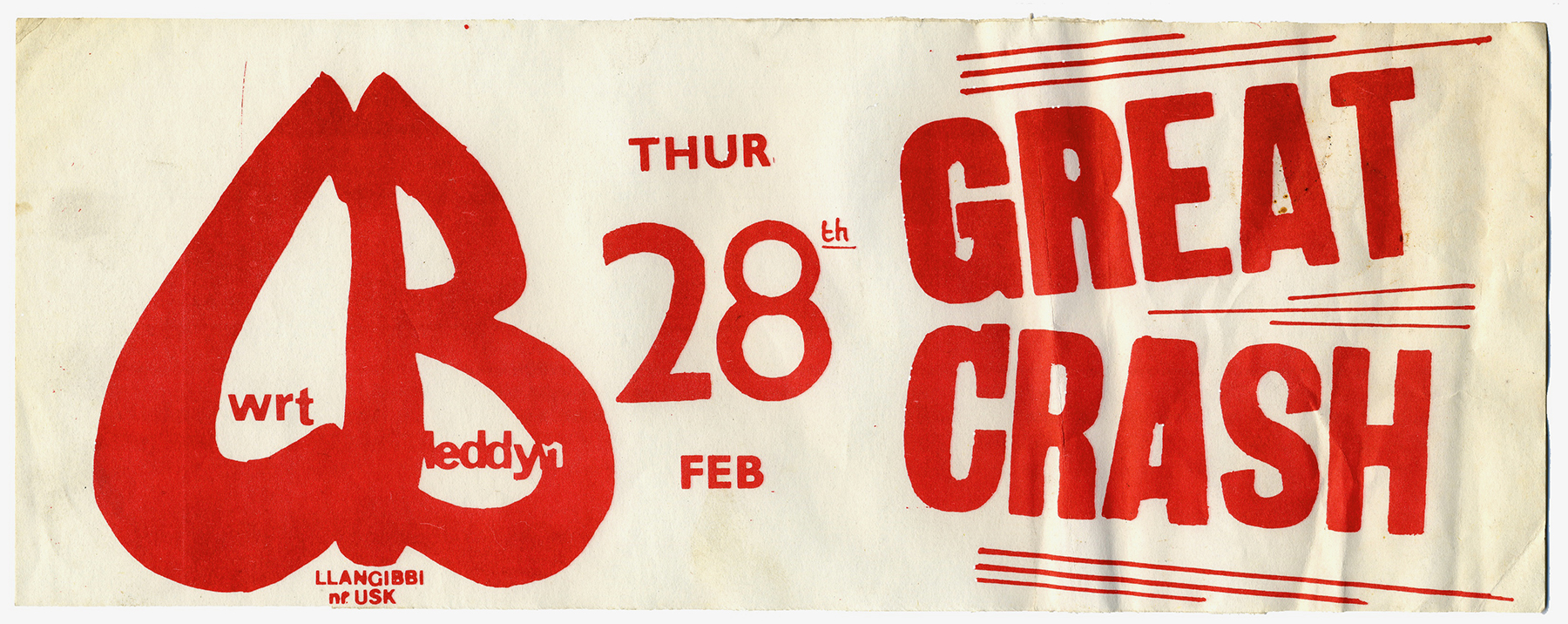

Al Gray: Possibly Cwrt Bleddyn. Halfway through a song, Piers (our drummer) stopped playing, leapt up from his kit, left the stage, strode through the audience to the back where he confronted two punters. “Yes, I AM very tall!” he shouted in their faces. “And YOU’RE very stupid!” He was over 6ft himself and I guess, a little self-conscious about his height. For some reason, he believed these two fellas were passing comments on his size … (?!)

There were other interesting gigs – the one where an audience member danced up, whipped down his pants and trousers, gyrating his equipment in front of a particular girl, only to be set upon by the girl’s enraged boyfriend and his mates who beat him to a blood spot.

The one where we supported arty French band Ange. At one point during the song, the keyboard player left the stage, returning soon after, having changed into a black leotard and cape, the better to theatrically illustrate the weird, spooky song they were playing. Unfortunately, in his haste while changing, he had neglected to tuck all his “equipment” into place. The result was him waving his arms around like a vampire with one of his testicles on full view, with the audience shouting “Oy mate! Your bollock’s hanging out!.” Perhaps owing to the language barrier, he didn’t seem to realise the predicament immediately, resulting in much audience appreciation.

The one where Piers had to lock himself in the band room protesting that he was gay in order to escape the amorous attentions of an enormous admirer.

The one where we were sacked after the first night…

The one where we were sacked after the first set…

George Benn: There was the time we deputised for an up and coming pop band (I think they were called Ice Cream? – anyone else remember?) at a venue in Swindon (I think). The room was full of young girls who were going insane over us because they didn’t know we were stand-ins for their heroes. I was at the front of the fairly low stage trying to sing while girls who couldn’t be a day over fourteen ran their hands up my legs. It’s no surprise to me that some of the stars of the day were helping themselves to their audiences.

Nick Smith: I also vividly remember the Ice Cream mistaken identity gig – confirmation that we were innately unsuited to becoming Grade A stage-strutting Rock Gods.

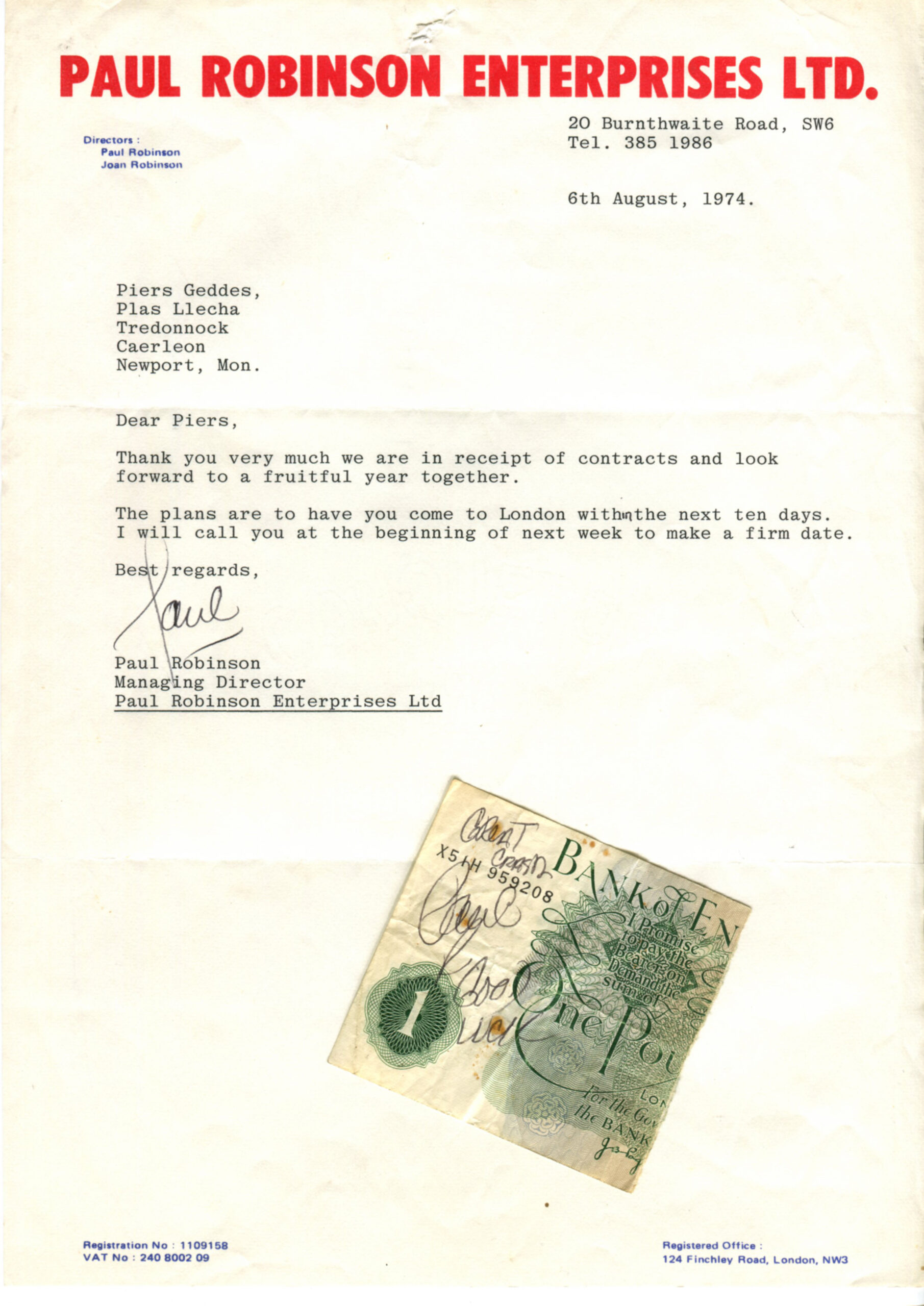

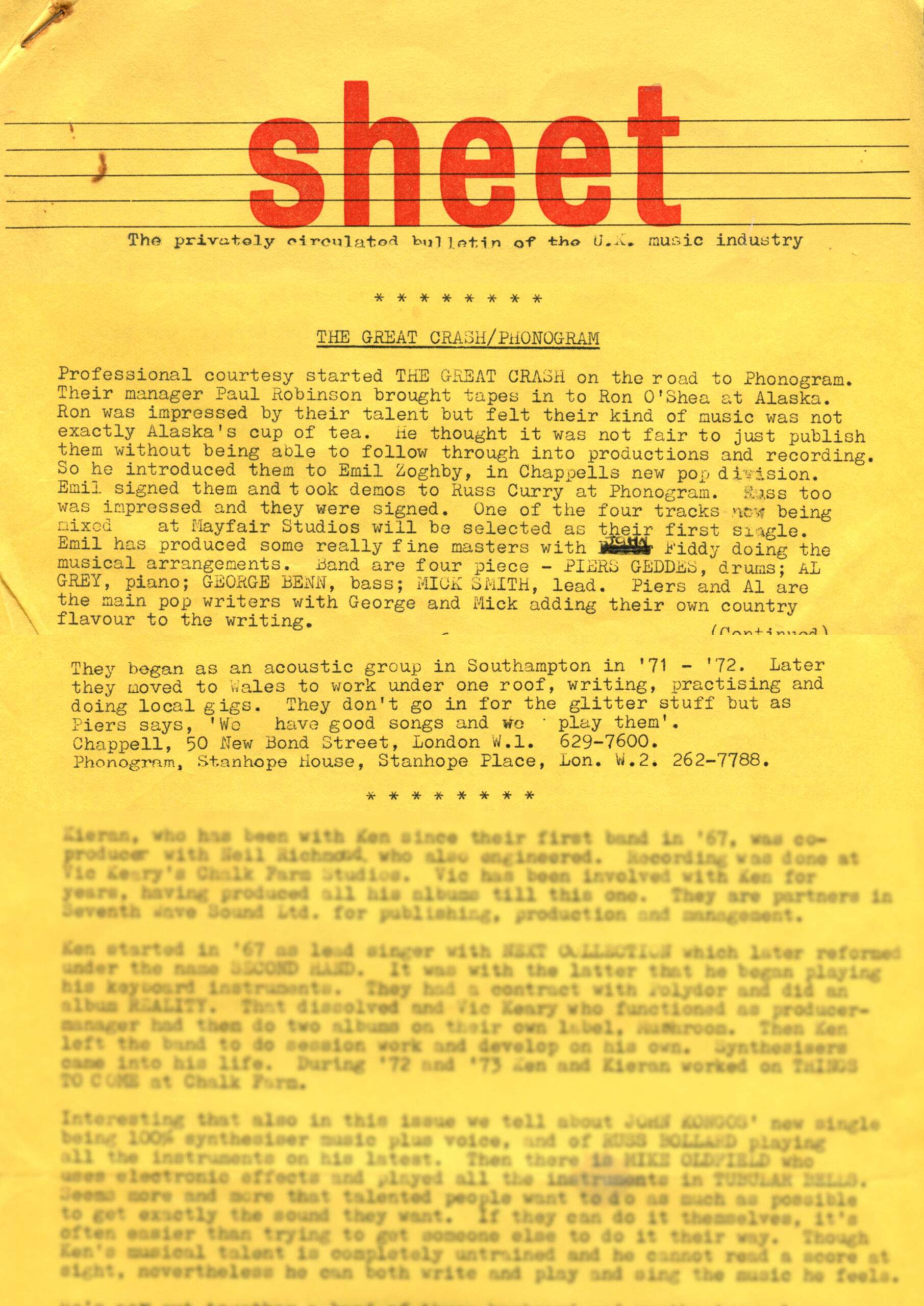

What led to the Polygram deal?

Al Gray: We were offered a number of deals – Raft Records (it sank), Van Van Music (a Belgian Waffle magnate), Shel Talmy and others. As with all of them, it was the quality of the demos (and I guess the songs) which attracted them.

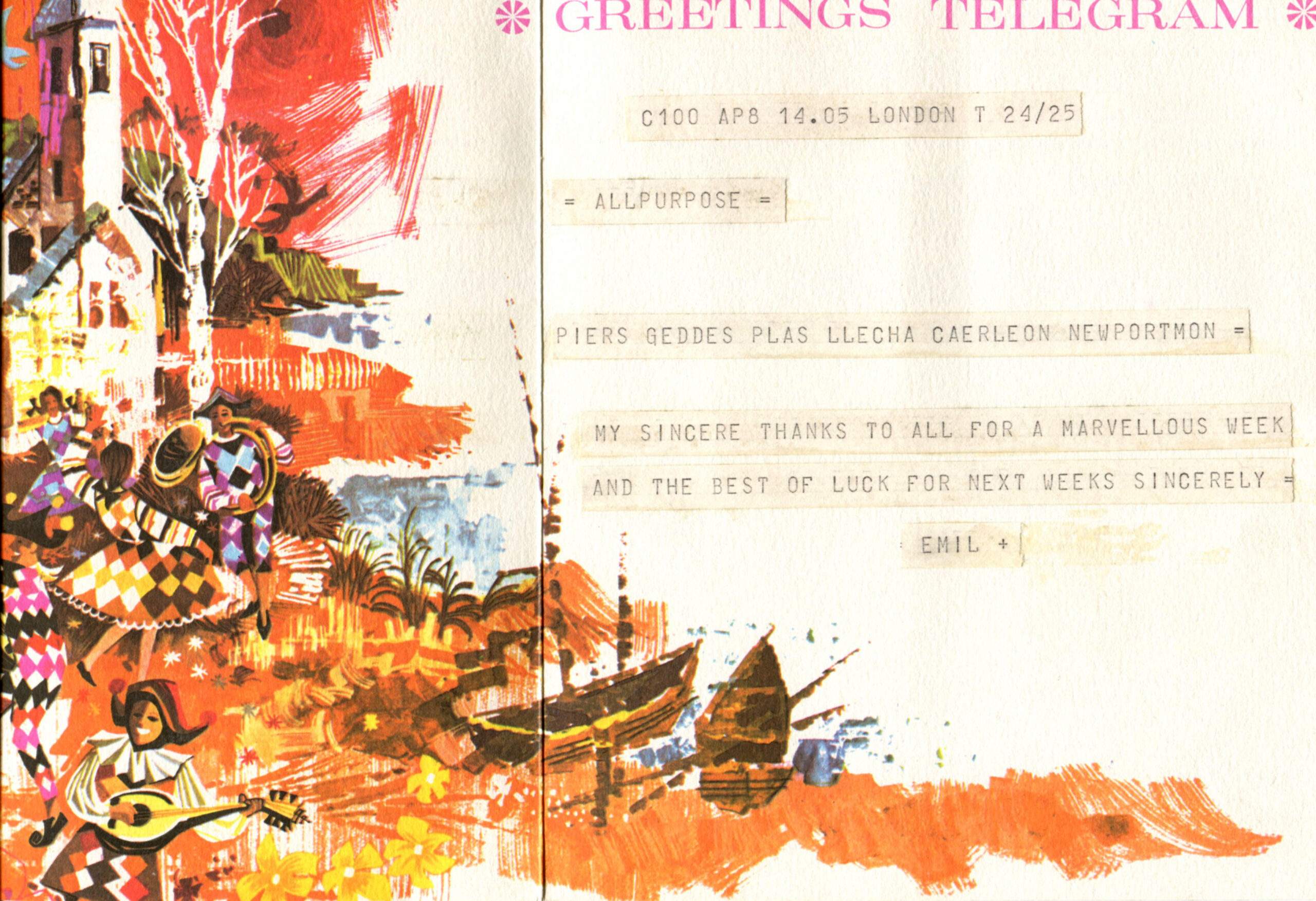

Nick Smith: We were getting desperate and disillusioned after 2 years of never quite making the cut, so when the Polygram deal was offered with Emil Zoghby producing we didn’t think twice. Contracts were signed and after a few days’ unproductive and drug-fuelled pre-production at Plas Llecha with Emil we went into Polygram’s Bayswater studio for what was for me a week of terror and embarrassment.

What circumstances lead Polygram to cancel the release of your album?

Al Gray: As I understand it, there was a shake up at Polygram and whoever had signed us was moved on. As we had no one “in our corner,” we were dropped. Added to which, it must be said, the recordings we did with them were not particularly good. They didn’t really know what to do with us. Our producer, Emil Zoghby, had come down to Plas Llecha a week or two before to rehearse us for the sessions. He brought with him a phial of liquid cannabis which we were invited to dip our Player’s no 6 and Sovereign ciggies into. Not entirely a good idea… He spent the rest of his time with us performing low grade magic tricks for reasons best known to him.

Nick Smith: Producer Emil Zoghby was a nice guy but not the right producer for us and it was obvious from the start that we were not going to come up with whatever it was that he had in mind. At the end of the sessions we went back to South Wales and waited for the results to appear – there was never any question of us being involved in the mix process. The final straw for me was that when some rough mixes did eventually arrive, almost all the guitar parts had been replaced by something with a lot more testosterone played by some anonymous session gunslinger. So it wasn’t a big surprise when we were told that Polygram wouldn’t be releasing the album.

What happened after the band stopped? Were you still in touch with other members? Is any member still involved with the music?

Nick Smith: After the Polygram disaster the Great Crash quietly disintegrated – happily without rancour between the band members. Al and I played occasionally with songwriter and performer Charlie Barber and in covers bands called White Lines and Homegrown (make what you will of those names). As above, Al had his deal with Charles Ward at Rockfield Studios and I think I may have helped out on one or two sessions there. George went back to Southampton. In the early 1980s I started up Loco Recording Studios – more on that later in the interview.

Over the years Al and I have continued to play on and off in many bands together. I’m still playing – bass in a couple of pub bands and guitar in a trio with two saxophonists.

Al Gray: When The Great Crash folded I thought I should get a proper job so I applied for a post as a teacher. To my horror and distress, they gave me the job. After a week, I realised what a disastrous mistake I had made and resigned. To my relief, I was told I would never teach again.

Nick suggested I might take some of the demos of mine and Piers’s songs up to Rockfield Studios to see what they thought. The result was a 5 year deal and two single releases, ‘The Sweetest Thing’ b/w ‘King of the Boppers’ and ’99 Octane Girl’ b/w ‘Roll On, Roll Off’ (under the name “Randy and the U-turns”).

After that I worked in a Jingle production team (with Nick at Loco Studios) as well as producing music and jingles for various South Wales businesses and low budget film scores before going on to produce videos. I have now finally found my niche as Writer and Musical Director of my local Village Pantomime.

I’ve continued singing and playing in local bands including the village band “Prolapse” (let it all hang out), “The Mighty Pledge,” a 60’s soul band and numerous others, often with Nick (do I NEVER learn?)

George Benn: I went back to Southampton to be with my girlfriend. At one point this involved getting a job as a porter at the University I’d graduated from (surely some sort of record) before we went to France (she had a job at the Uni in Bordeaux) where we eventually broke up. I returned to England, spent two years working as a van driver for friends of ours and then got a proper job in IT. We did a reunion gig in 1977 for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in Usk, if I remember correctly, and we’ve stayed in touch ever since, although this has mostly been via Christmas cards. The others get free copies of my CDs (three to date) because I know where they live. This increases the distribution quantities no end.

I’ve been playing guitar in traditional folk band Innominata for forty years (!!!) and for the last twelve years or so in the covers band Inside Track (on bass again) with my old Uni mate Chris on guitar.

Piers Geddes: I became a civil servant but that didn’t last long and I turned myself into a makeshift business mogul. Meanwhile I went drumming for a small local dance band which was good fun, playing waltzes and quicksteps before the rock ‘n’ roll of the post-bingo second set. A piano came my way and I learnt how to sound as though I could play it and joined a blues band. Then, over several years, I wrote and recorded three albums – using local studios and musicians – until my hearing disintegrated completely. But I am still songwriting!

Plas Llecha later became a famous Recording Studio. How do you remember it? What kind of gear did you use?

Nick Smith: I was always just as interested in recording as in playing and writing – and in the late 1970s started to think about the idea of opening a studio with Roger Grey, a friend and drummer in a couple of bands I was playing in at the time. When my partner Jane and I finally moved out of Plas Llecha I kept on the lease and in 1981 I was left a small amount of money which enabled Roger and I to start up Loco Studios.

Initially it was a very primitive setup but we were busy from the start as the Portastudio had only just been invented and local bands were desperate for somewhere cheap to record. The studio grew and grew until, by the time we sold it in 1996 to the band Asia, we had recorded albums by Oasis, The Verve, Julian Cope, The Sawdoctors, Shed Seven, Ash, The Levellers, Boo Radleys, The Bible … and many others.

Our first recorder was a Cady 8-track (built in a garage by enthusiast constructor Steve Waddy) used in tandem with a Dynamix 12 channel mixer and various other bits of kit. One of the Cady’s many unendearing features was that it lacked even a rudimentary tape counter or timer. This caused an early and near-fatal (for the engineer) disaster – the unintentional erasure of a completed song in a demo session with The Damned’s Paul Gray.

When we sold the studio, the desk was a 56 channel SSL and the main 24-track recorder was a Studer A800 (which did have a very expensive tape counter).

Are you excited about the upcoming vinyl release? How involved were you with the reissue project?

Al Gray: Yes, it’s certainly unexpected. I personally have had little to do with the reissue.

George Benn: I was amazed when the whole question of releasing our material came up. It has been fifty years, after all. But I have to assume there’s a market for it.

Nick Smith: It’s great – though I hope Seelie Court will also put the albums online with Spotify, Apple Music et cetera as I’d love the stuff to be more widely heard. My involvement was to assemble all the material for Seelie Court.

Is there any unreleased material?

George Benn: There are quite a few songs that weren’t on the ‘Deadfire Echoes’ album which I suppose Seelie Court will release in due course.

Al Gray: Yes, I believe a second CD is lined up.

Nick Smith: There are about 40 Great Crash songs recorded in that period and it would be great for some more of them to get a release.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

Al Gray: Difficult. I always enjoyed writing with the other members of the band, especially Piers. There was always plenty of laughter (I laughed my tits off a long time ago). Reading George’s comments below, I certainly agree. We were extremely lucky to have that sort of experience which isn’t really available for young people today. Rent was £20 a month for the house, food budget £5 a month (we ate like Kings – no, paupers actually!). Petrol 25p a gallon or something crazy. And nothing to do but play music.

George Benn: I suppose the highlight, if it could be called that, was the fact that we tried it in the first place. Even though we didn’t succeed, it was a great experience which I wouldn’t have missed for the world.

Nick Smith: At the time I think I found it quite stressful – there were moments where it all seemed to come together but many others when I wondered what on earth we were all doing! The most satisfying thing for me was to reach the end of a complex and difficult recording and arrangement – like say ‘Regimental Reunion’ – and to feel that we’d created something a bit different. Some recorded solos and overdubs – ‘Magnolia Street,’ ‘Deadfire Echoes’ and (most of) ‘Beyond the Pyramids’. And there in fact were some really good gigs, including a weekly residence at Cwrt Bleddyn – a local club where we had quite a regular following.

Piers Geddes: So many highlights – lyrics you’re pleased with, lyrics transformed into a beautiful song by Al, drumming moments at gigs when the band was really cooking, hearing a song successfully recorded. Playing on John Peel’s show. Auditioning for Bernie Taupin and Rocket Records (it led to nothing) and hearing him say “I wish I’d written that song.”

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

George Benn: Thank you for your interest in us. And as I’m writing this on the day the obituary of the last original member of Lynyrd Skynyrd was published I’ll also give thanks that we’re all still around to enjoy whatever success is coming our way (or not).

Al Gray: I used to look back at The Great Crash years as a failure. This may sound like justification from someone who didn’t succeed, but judging an experience purely on how much money you made is a big mistake. I often think, having something of an addictive personality, that if we had “made it big,” I would have died a long time ago.

Nick Smith: It’s been good to pick over the past times – and to realise that maybe it was a bit more of a success than we thought at the time. Coming back to listen to the material again I can recognise lots of good stuff in the playing as well as the writing and arrangements. We lived and played in a bit of a bubble at Plas Llecha and being there, in our own primitive studio, was for me where the band was at its best.

Piers Geddes: There’s an awful lot to be grateful for. But two things stand out. We all made a contribution but Al’s generosity as well as talent in musical arrangements I quite took for granted. He was always ready to jump in and make a song better, adding harmonies or instrumental breaks. The other was Nick’s recording skills – without them there would have been no record of our strange few years in the dark Welsh countryside.

Klemen Breznikar

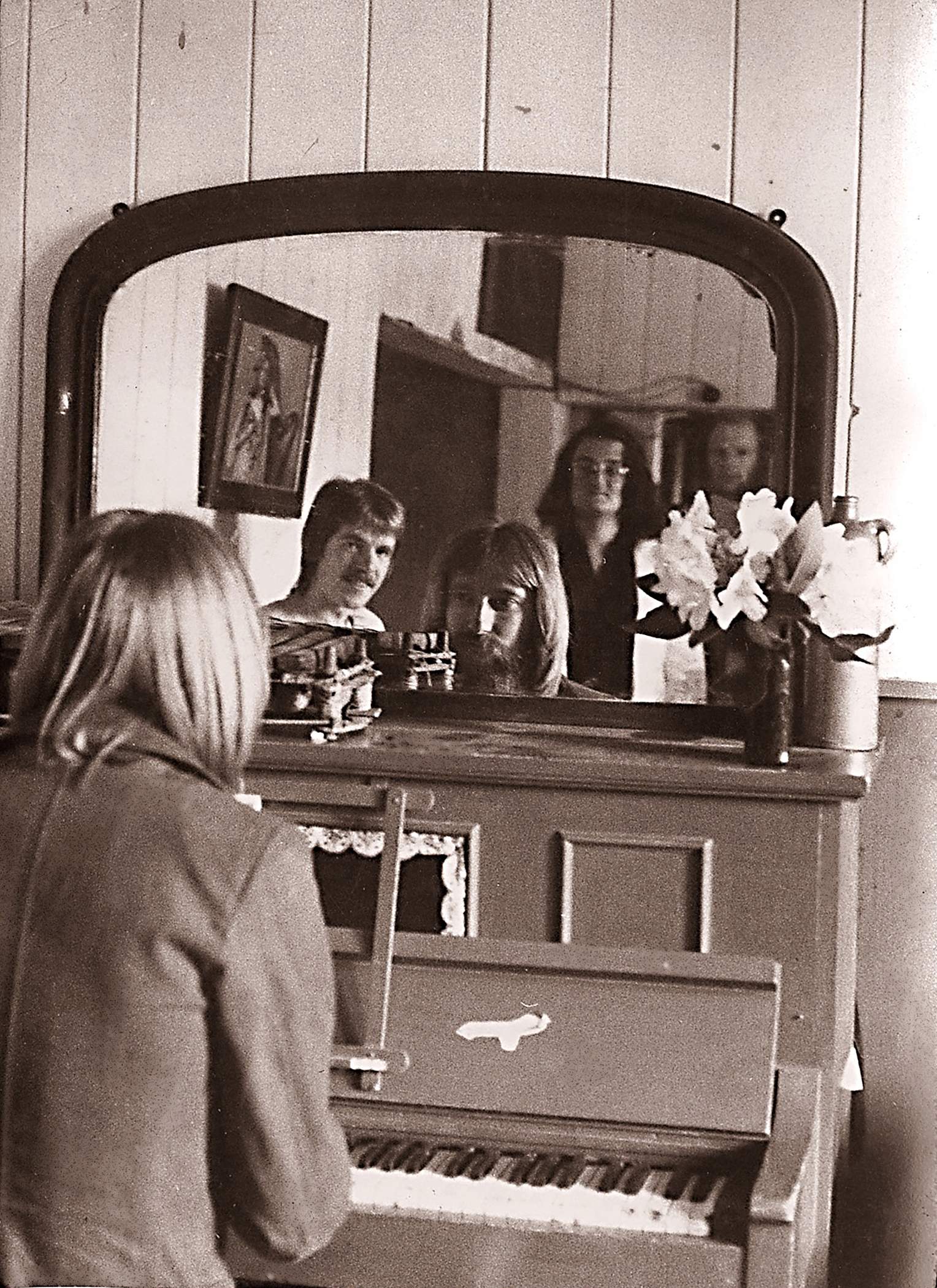

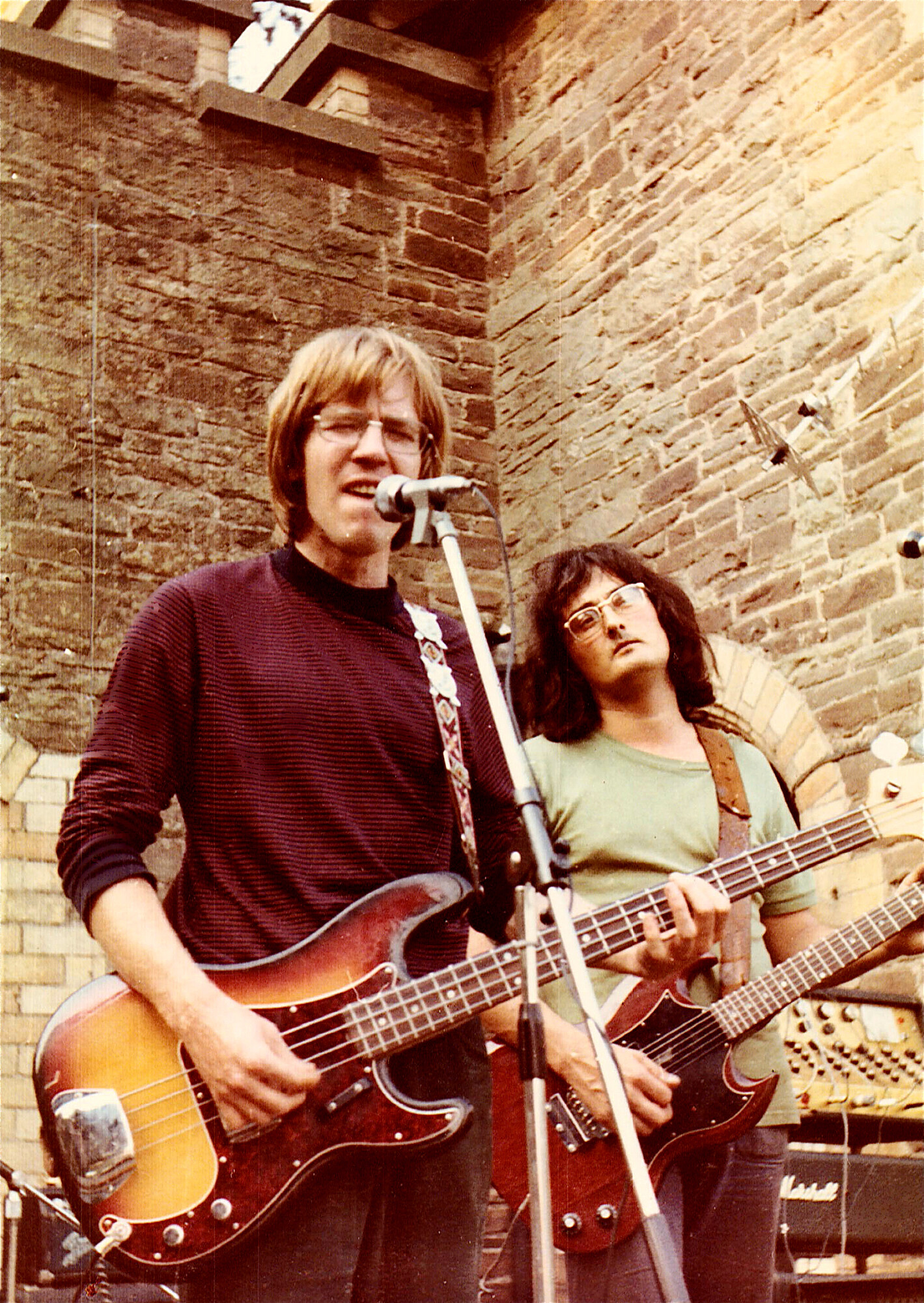

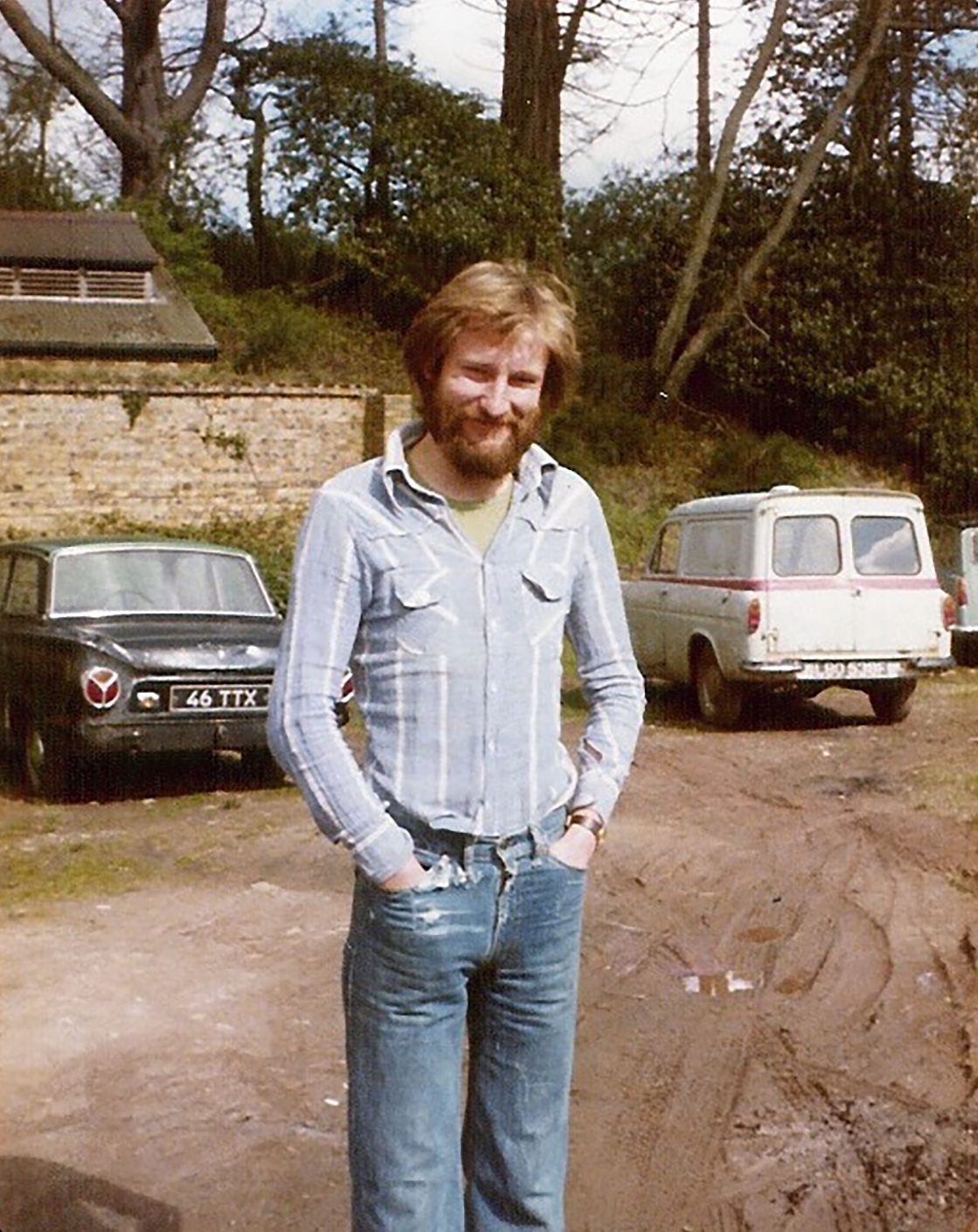

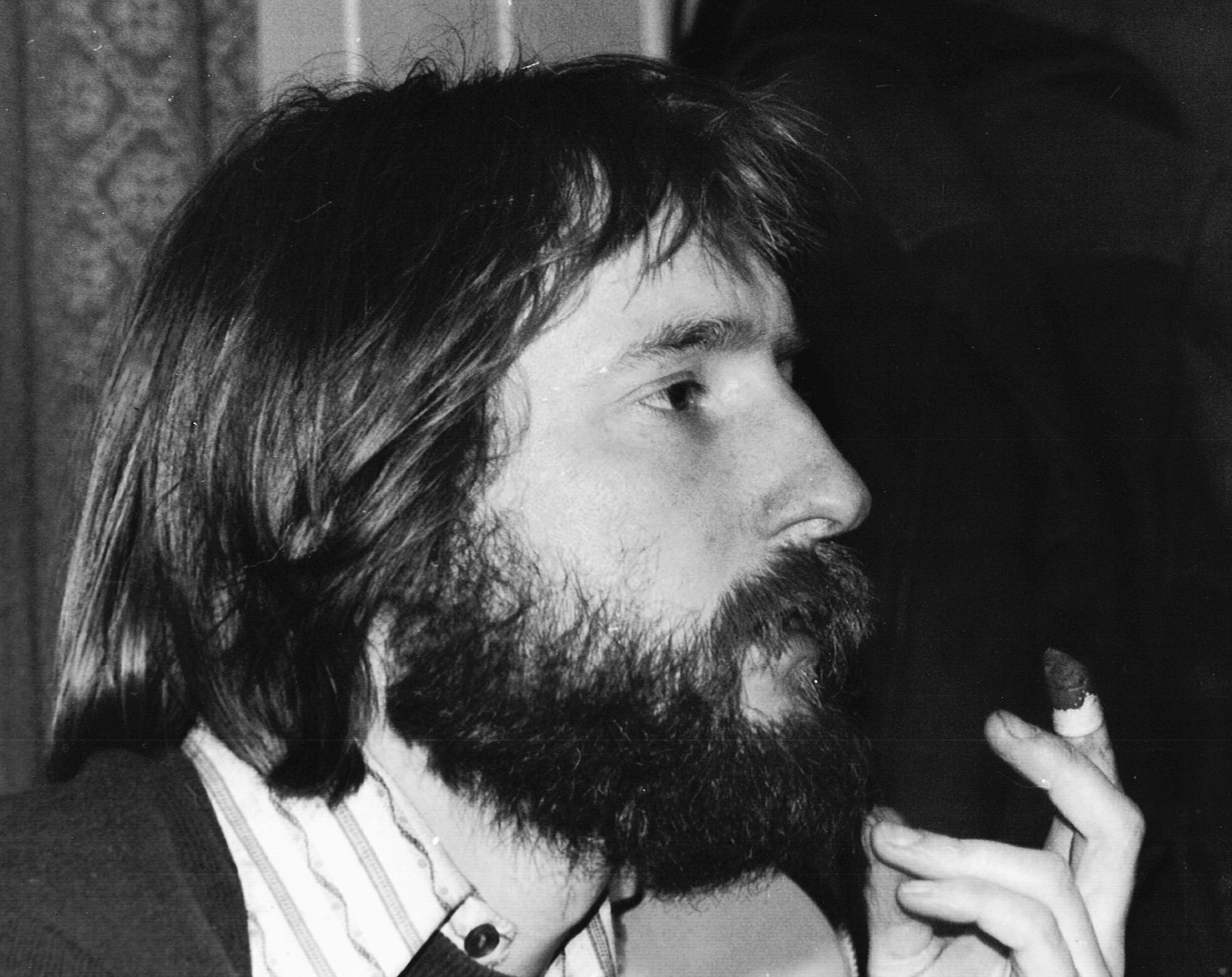

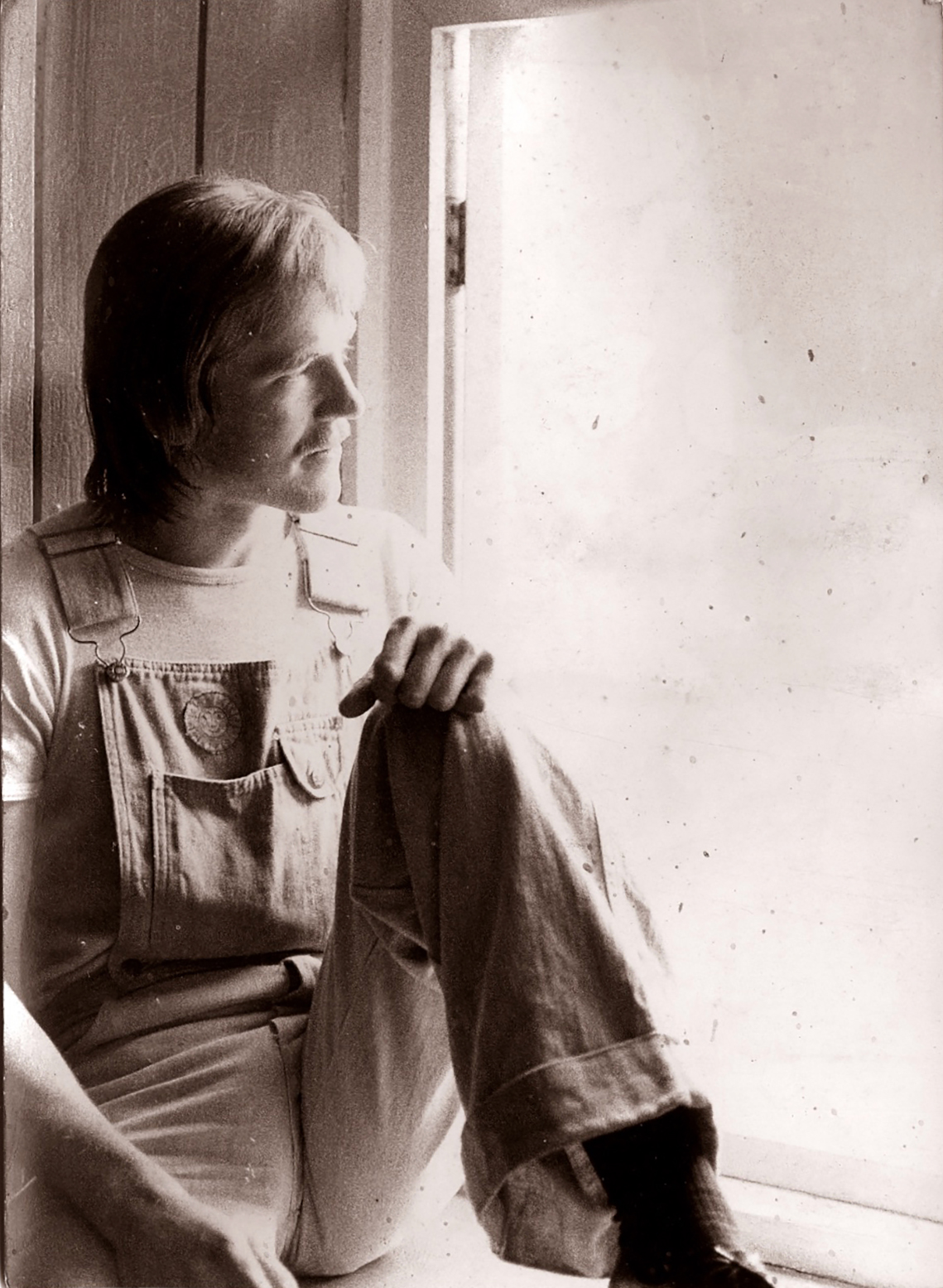

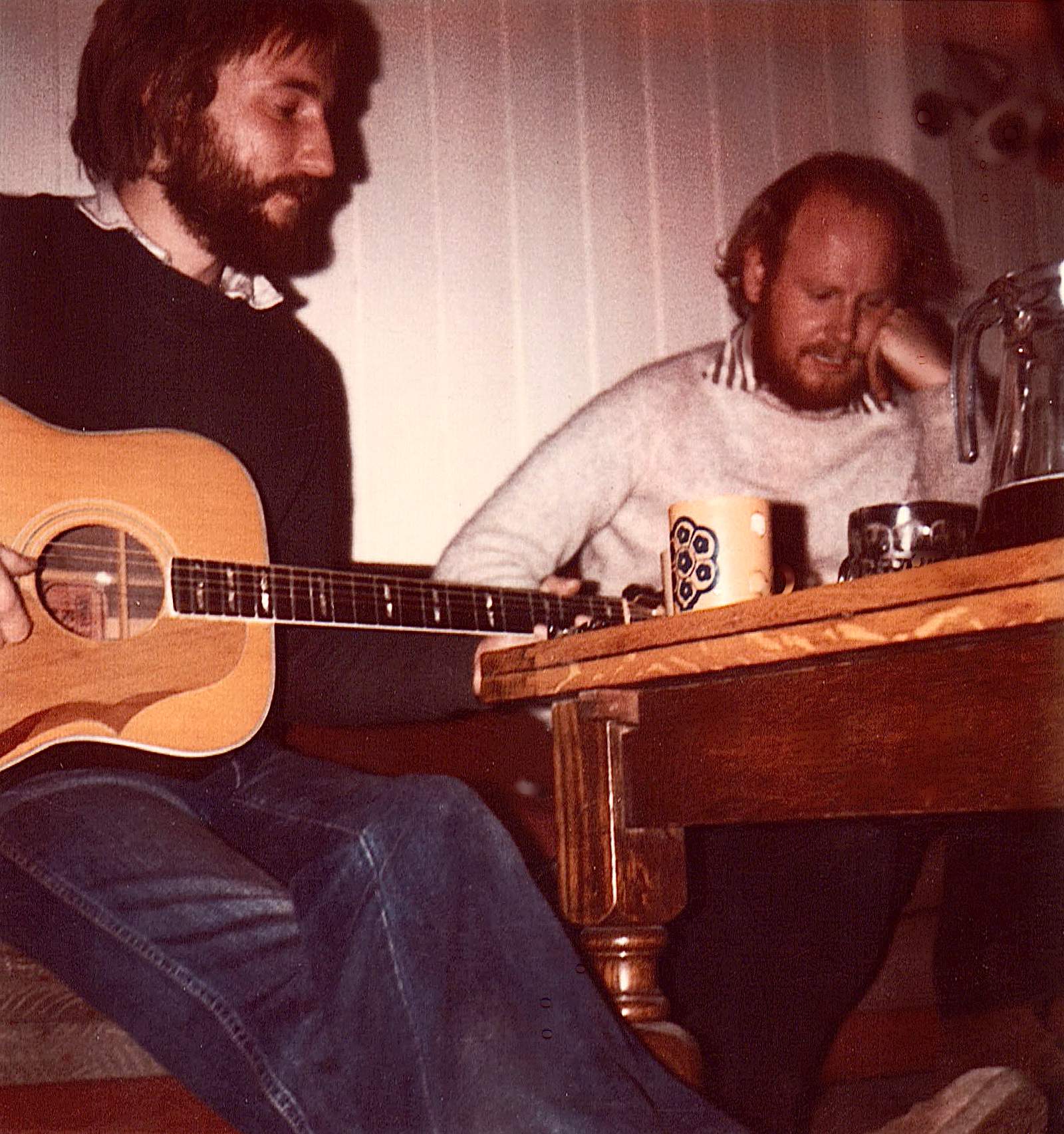

Headline photo: The Great Crash rehearsing outside Plas Llecha | Photograph: Nick Smith

Nice interview and good photos that take one back to that great era. Always a treat to come across a.new vintage band to check out.

I’m glad to hear Seelie Court are going to be issuing a second Great Crash cd,and also to read about the connections to the Bertie album,i had no idea there was a connection in members with Great Crash and Bertie,as i have BOTH Seelie Court cds…….after reading this interview,i must say the chaps come across with good humour,and self depreciating too,but i must spin both the Great Crash and Bertie cds again,.So thank you again got another fine interview.

Great long-form interview; a nostalgic deep dive into the band’s history and music. Love the track- an absolute classic – can’t wait for the album’s release.

So sorry to hear recently of the sad passing of Piers. Also that of Nick Stevens.

I had the pleasure of playing guitar for a couple of numbers with ‘ The Great Crash ‘ at a gig in a social club in Newent . I spoke to a member of the club before we left who commented that ‘ we don’t have many bands of your sort around here’. Wondered what he was on about until I saw a poster on the wall advertising ‘ The Gay Crash’.

I stumbled on this abfab article this morning, sadly the day of Piers Geddes’ funeral. What a wonderful collective experience.

I met Piers during his brief time in the civil service, possibly starting on the same day in July 1975 at the Business Statistics Office (BSO) in Newport. He lived in Usk at the time, opposite the wonderful Royal pub/hotel. After he left the BSO he started a company, C & D Oil, that later supplied the oil drums for the BSO rafts in the Monmouth Raft Races in 1977 and 1978.

Piers later went on to open Rocky’s, a very successful American burger resaurant in Baneswell, Newport. A wonderful guy.

I came across this article while researching the history of Plas Llecha, which was built by my great great grandfather Edward Windsor Richards, a successful steel engineer, in 1880. I have no idea if I am therefore a distant relative of Piers Geddes. The music is extraordinarily good and I have bought many copies of the CD to distribute to family and friends. Congratulations on the music, and on the interview, which brings it all to life.

Thank you for this article, I was the tape op/house engineer just after John purchased it in 1997 and frequently had to plug all Geoff’s synth back together after they’d toured.

A trip down memory lane.