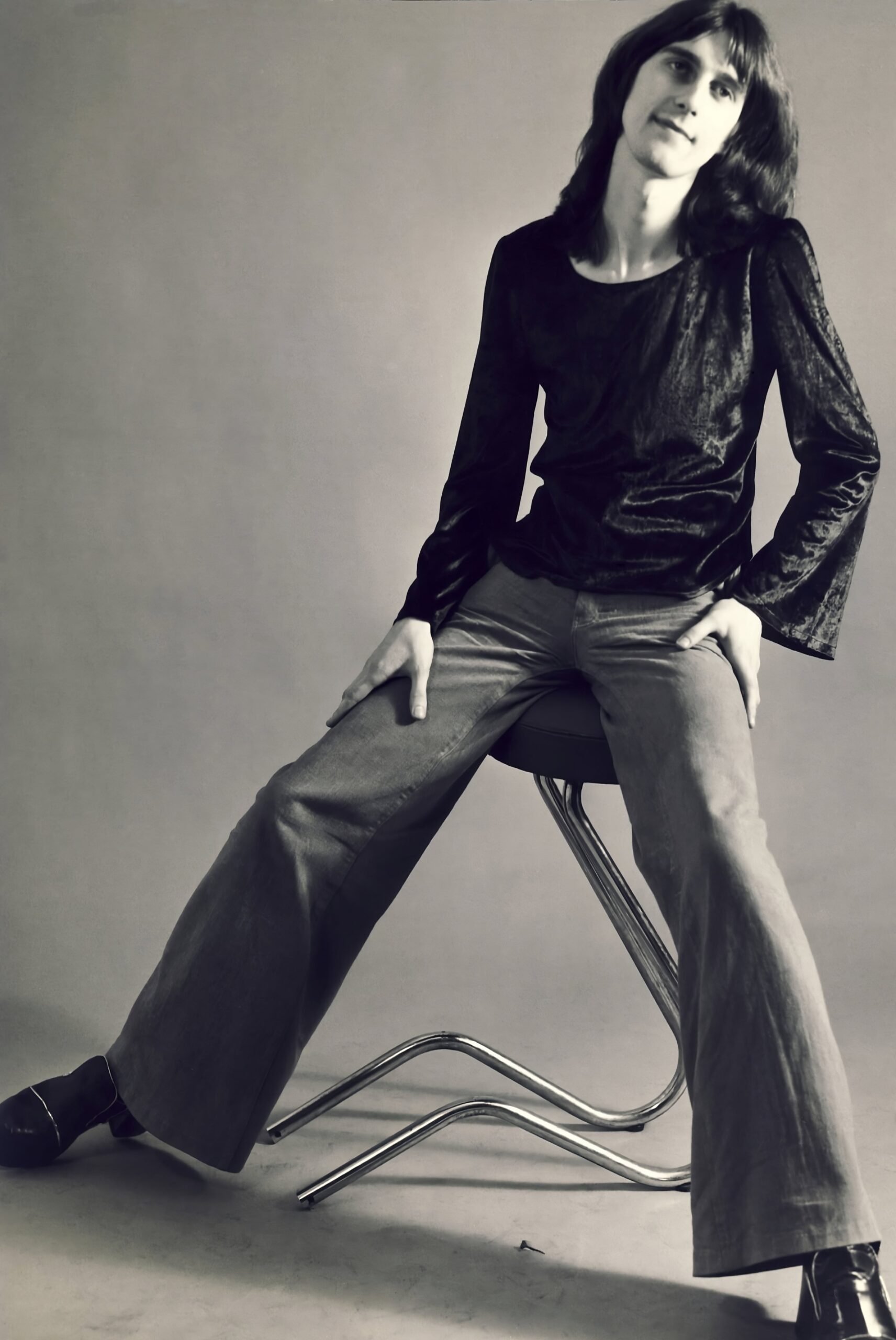

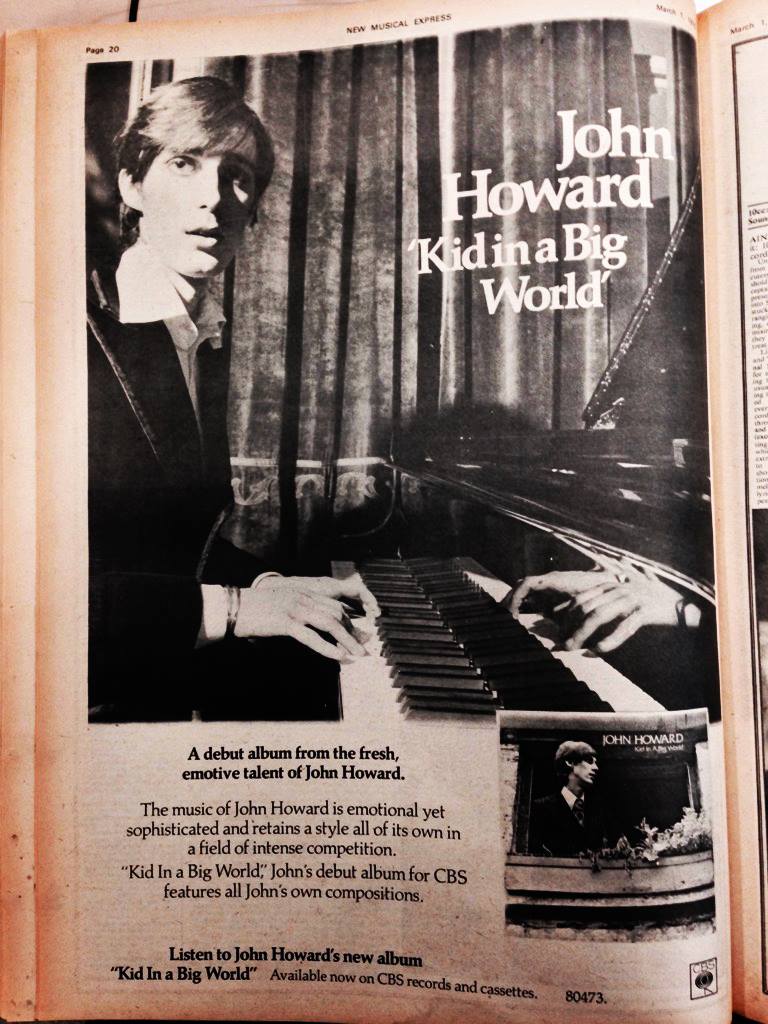

John Howard | Interview | “Kid In A Big World”

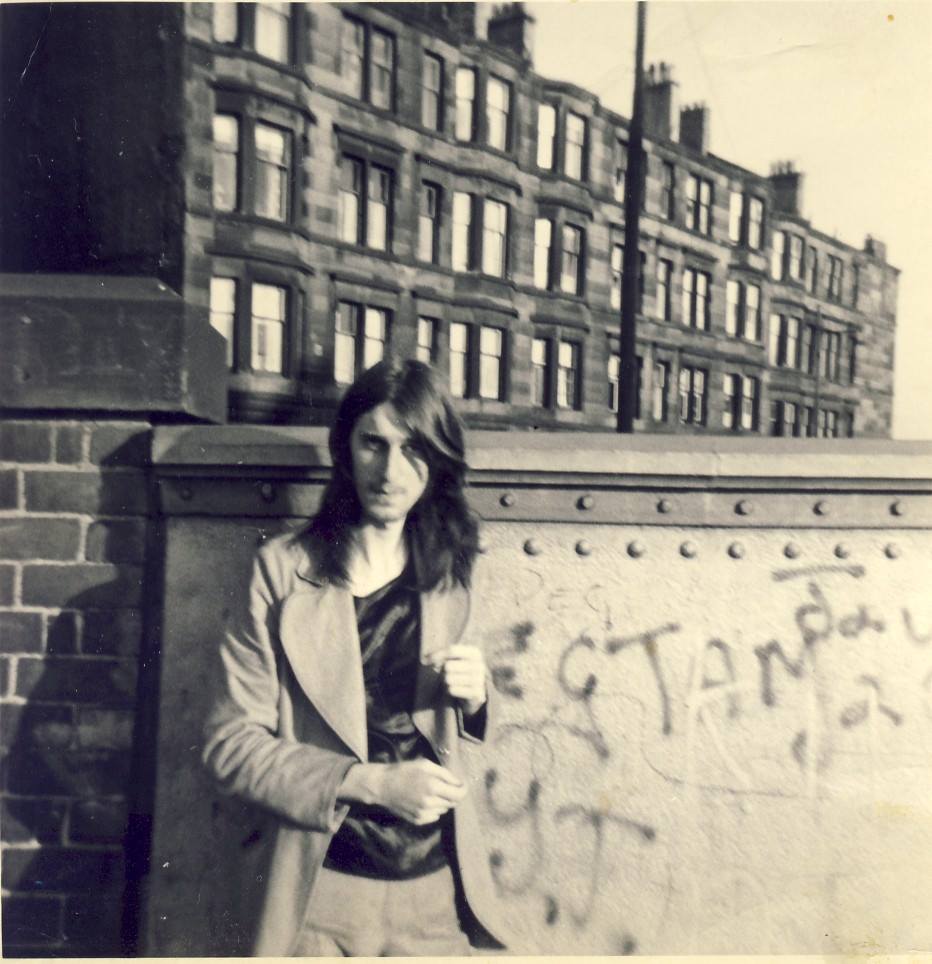

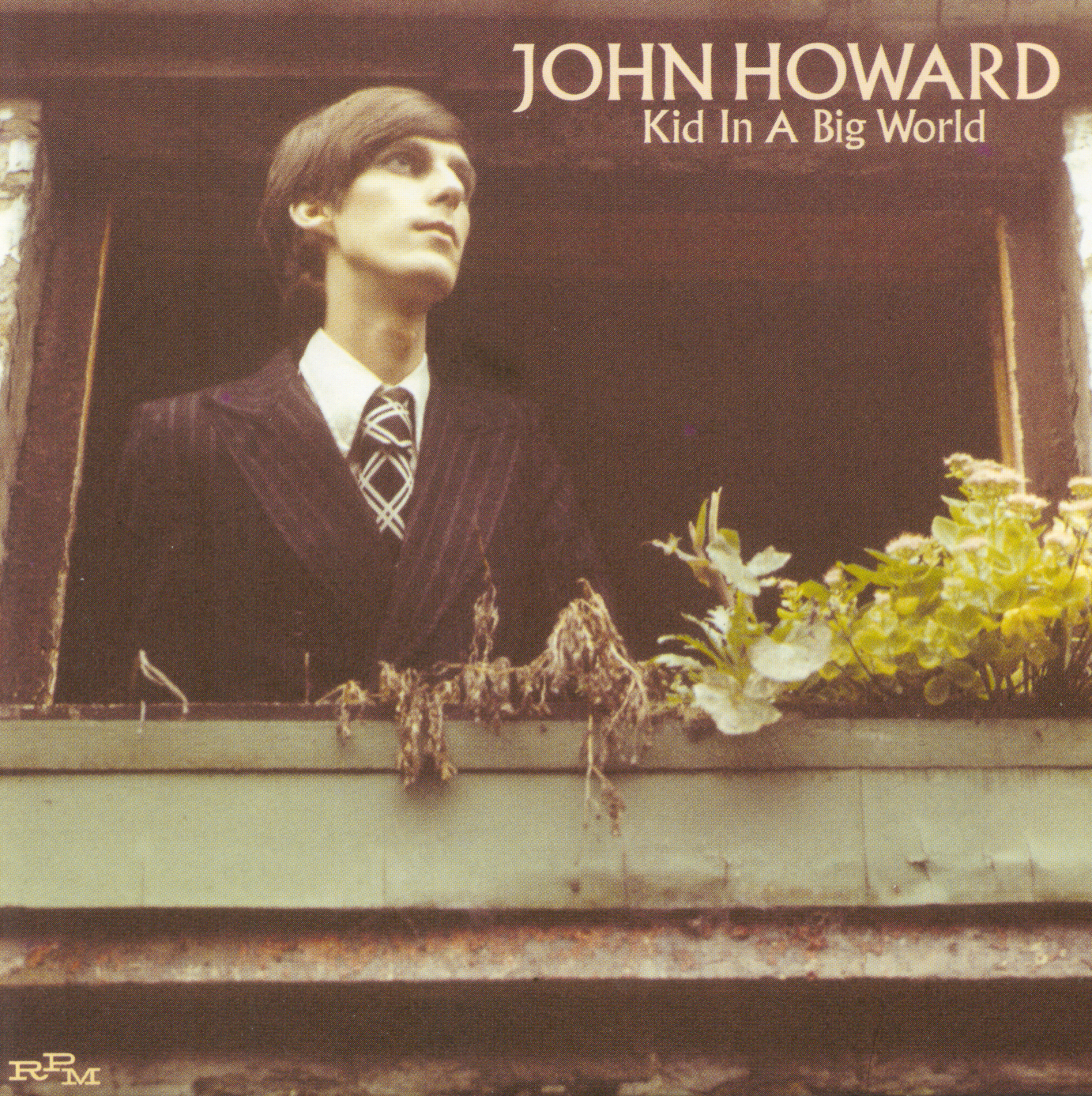

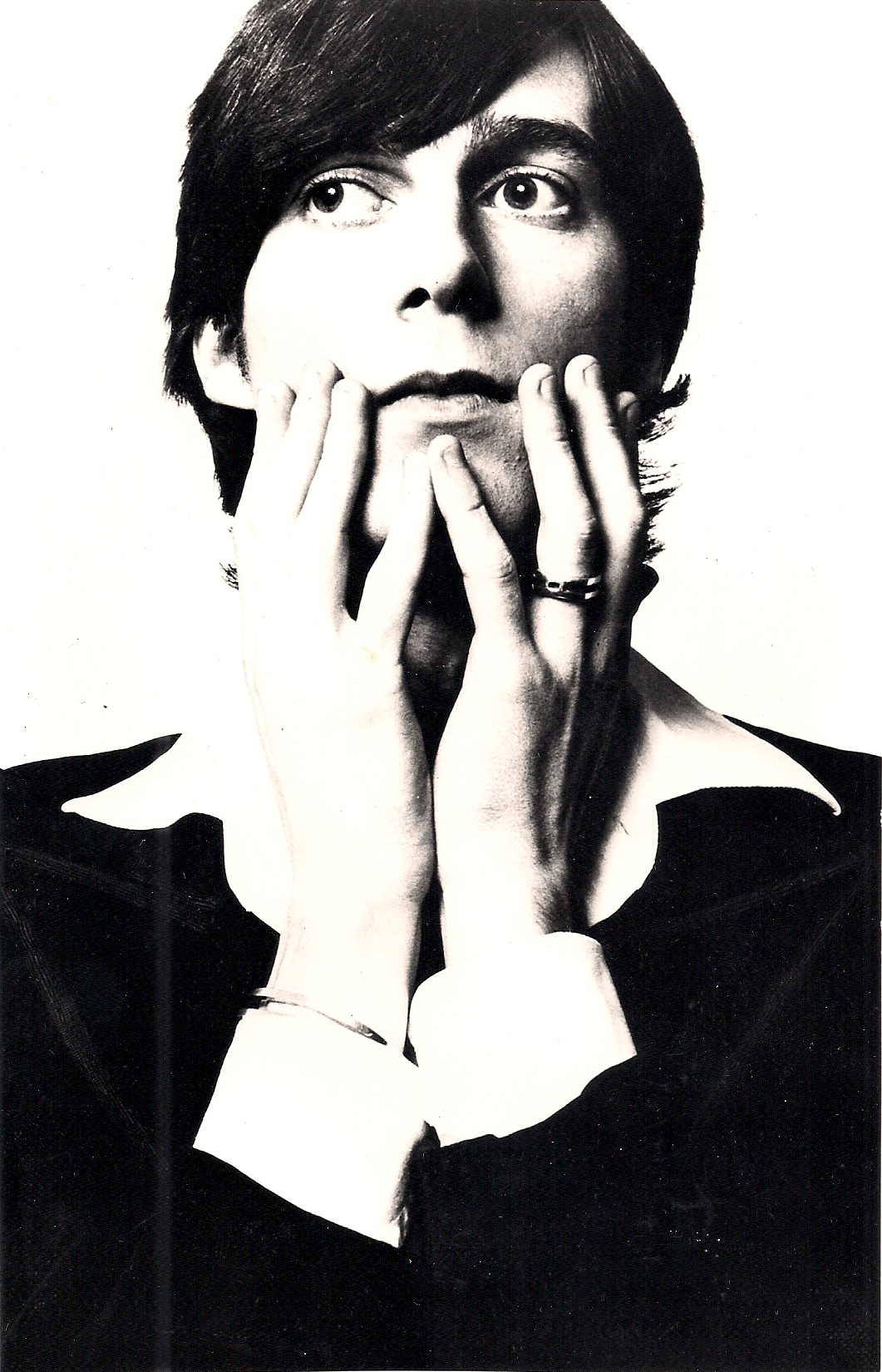

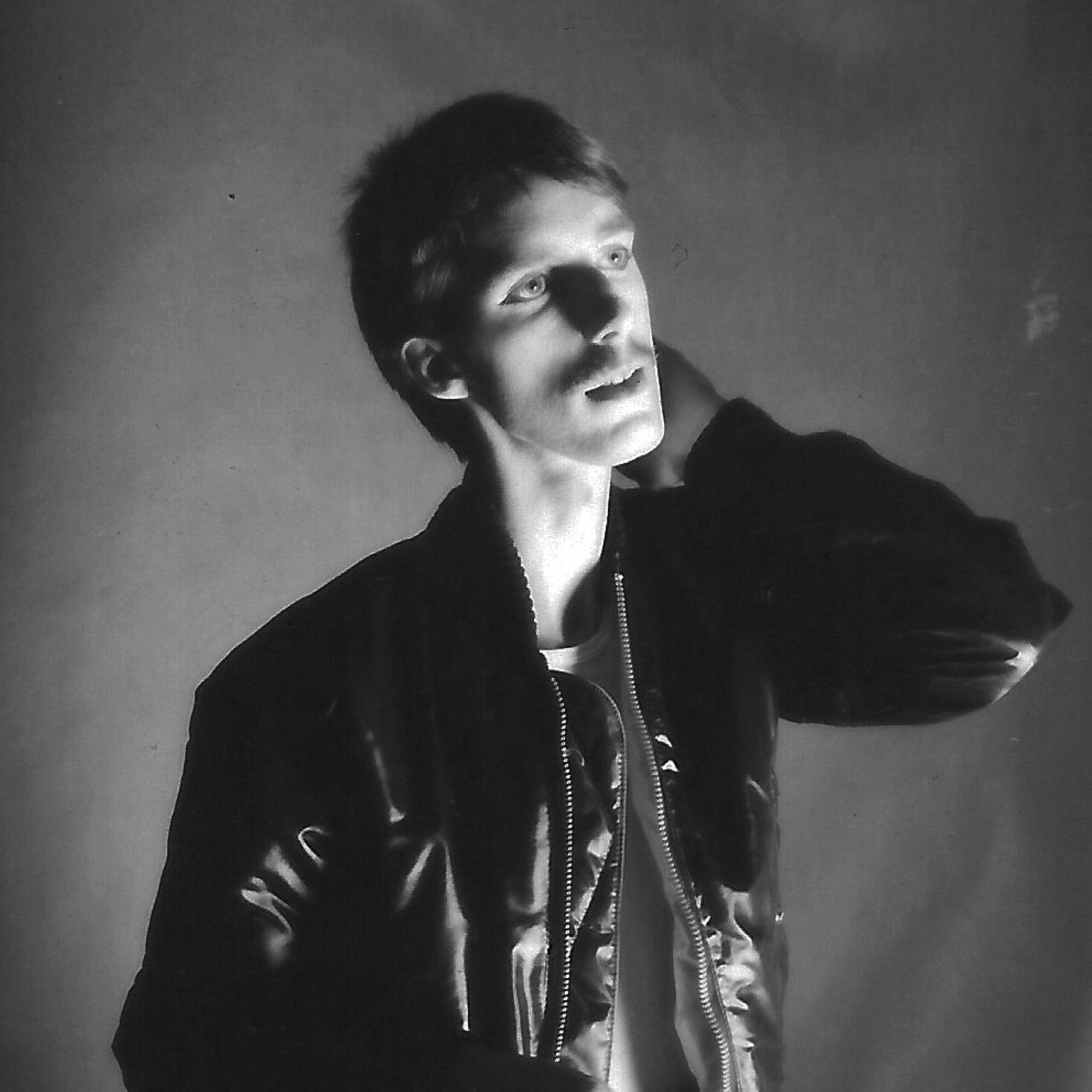

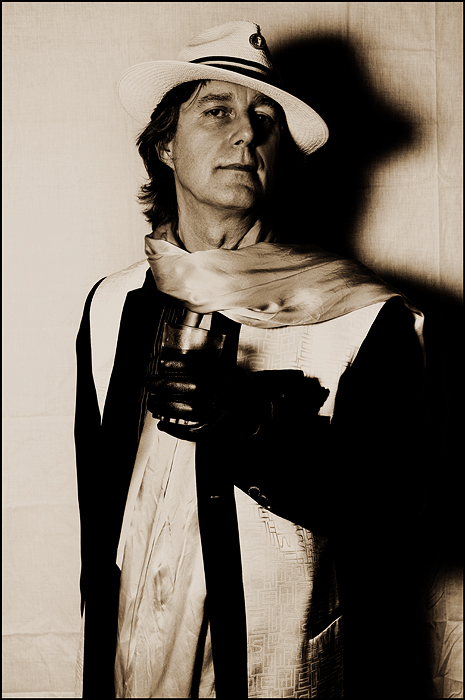

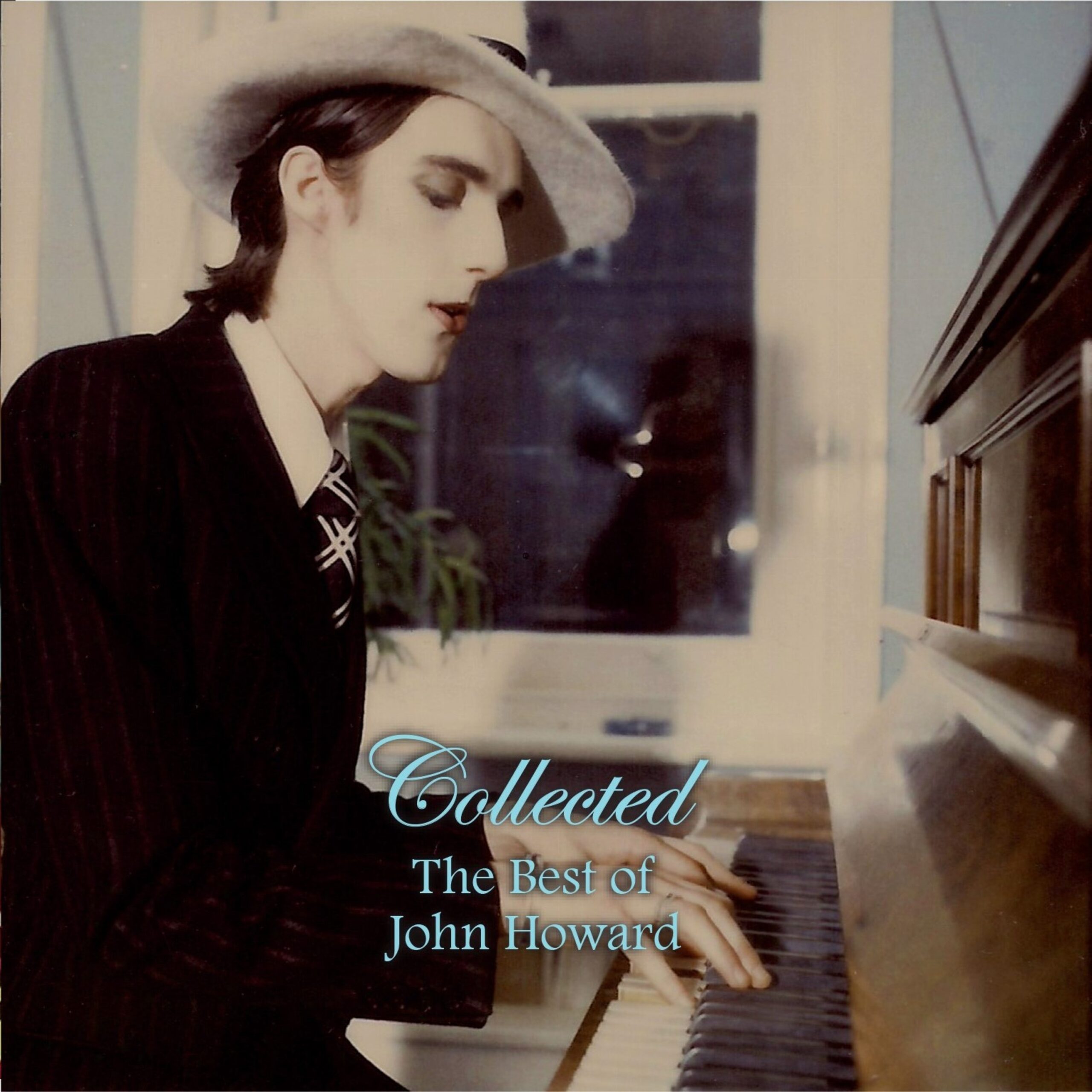

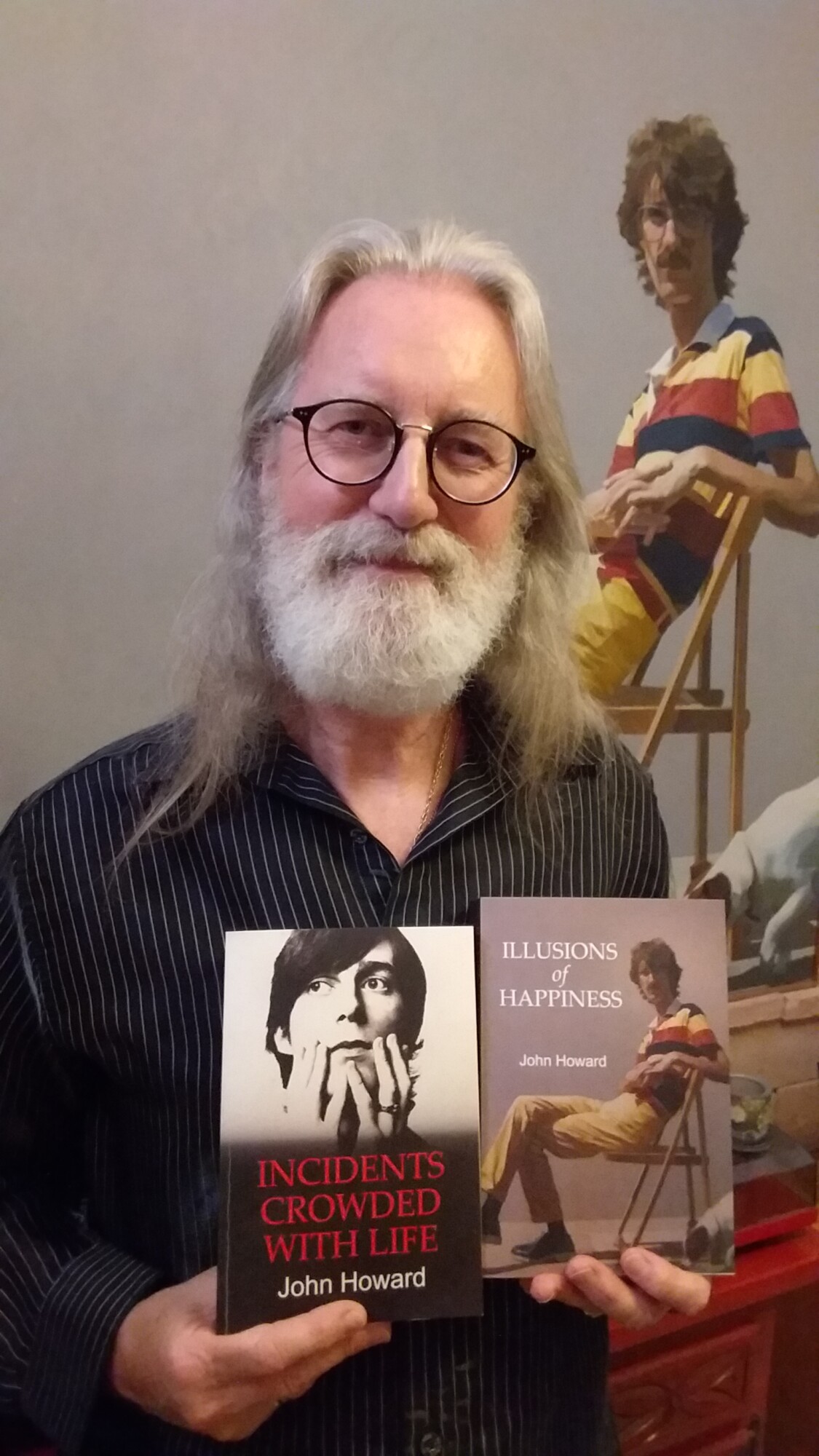

John Howard is an English singer-songwriter and pianist who rose to fame in the 1970s with his debut album ‘Kid In A Big World’. He was part of the glam-pop wave and has released over 16 studio albums and 11 EPs throughout his musical career.

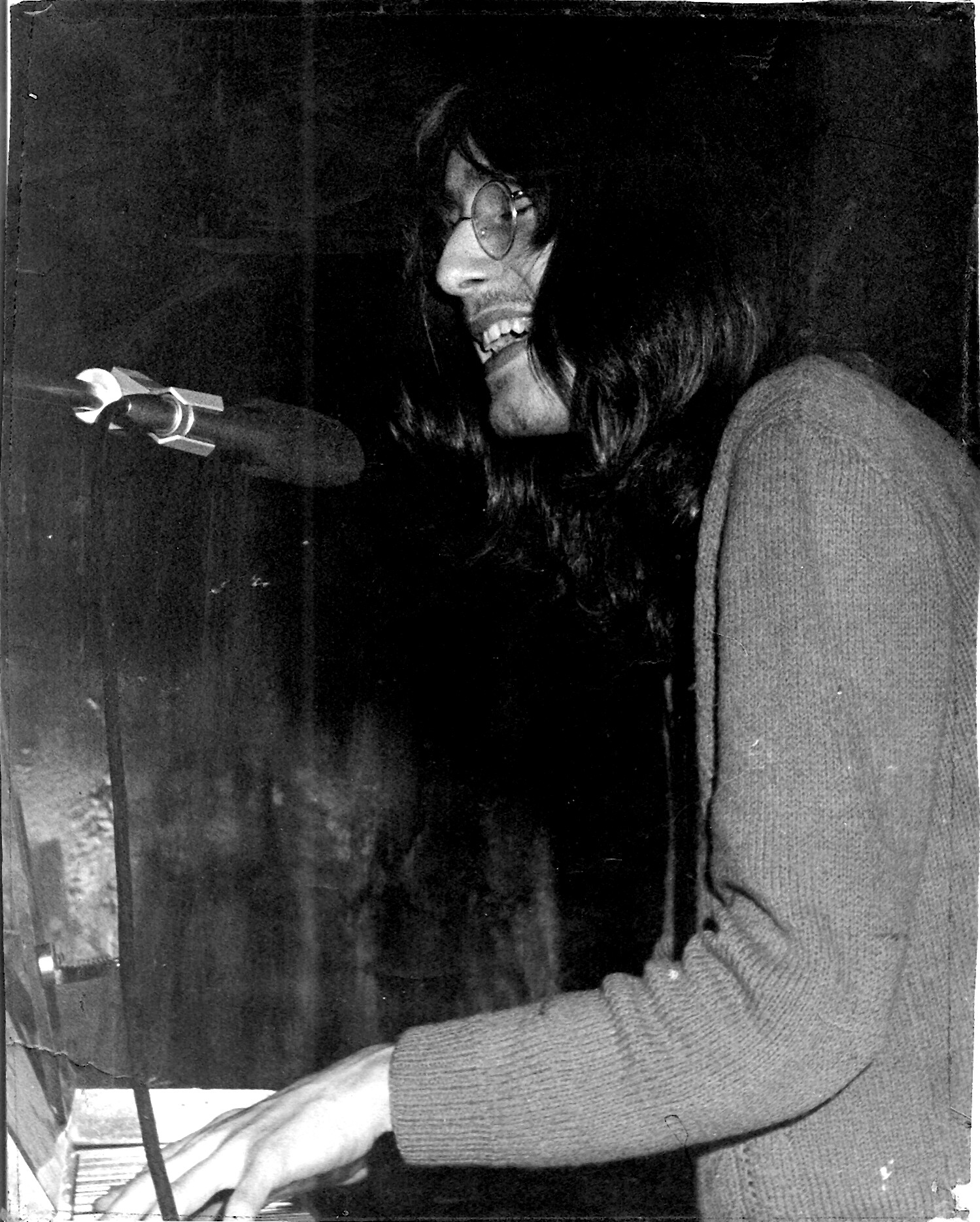

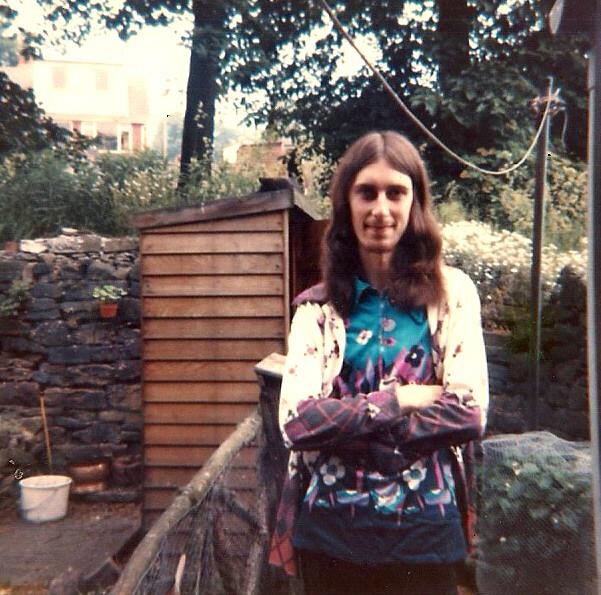

John began playing the piano at the young age of four and first performed his own material in 1970. In 1973, he was spotted by Stuart Reid, Head of Pop at Chappell Music, and signed to CBS Records, recording his debut album at Abbey Road and Apple Studios. However, despite some initial success, he left the label in 1976 and went on to record with producer Trevor Horn, but took a break from music in the 1980s to work in marketing and A&R at various record companies. In 2001, John Howard restarted his music career after retiring to Pembrokeshire with his partner Neil France.

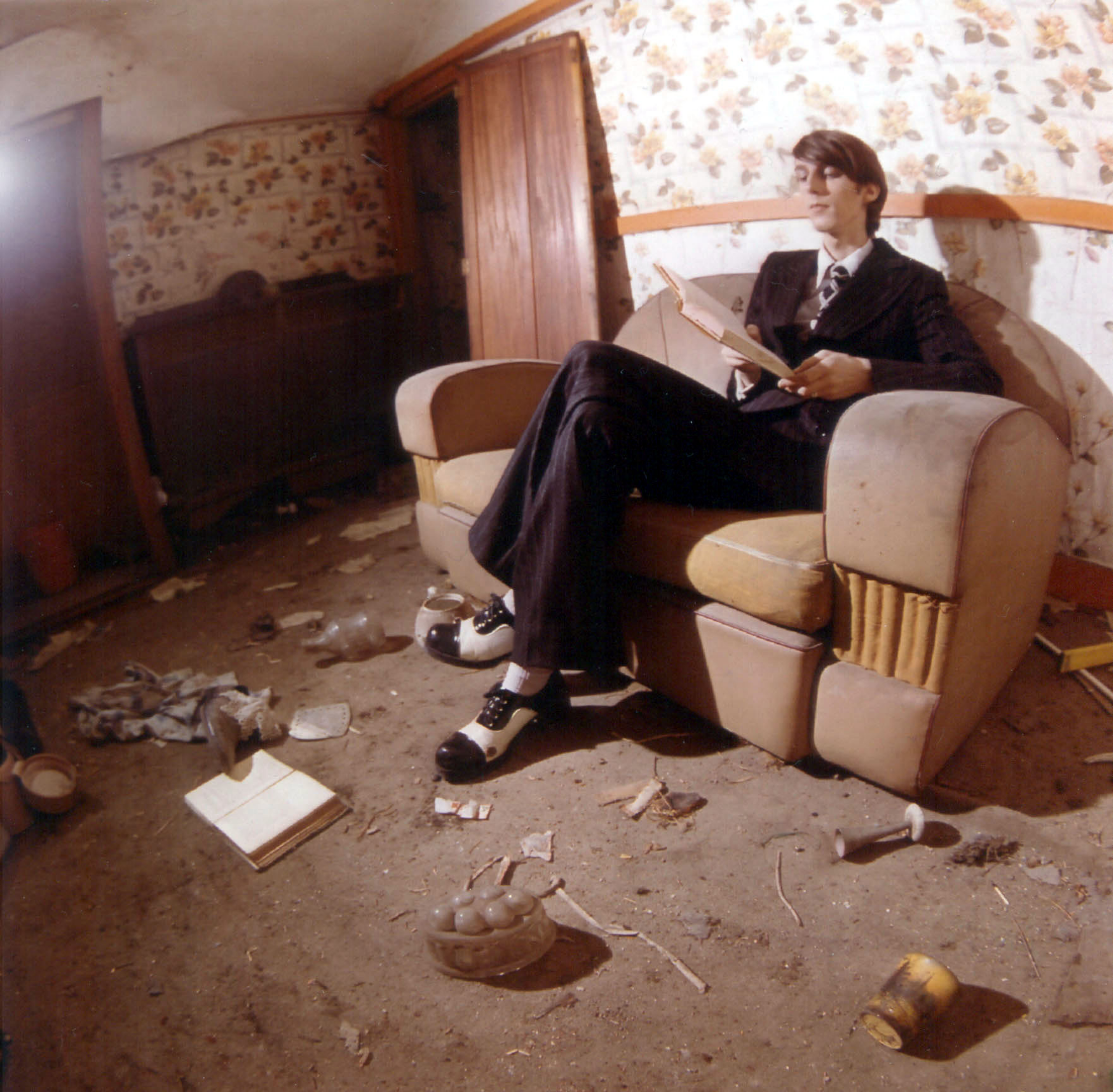

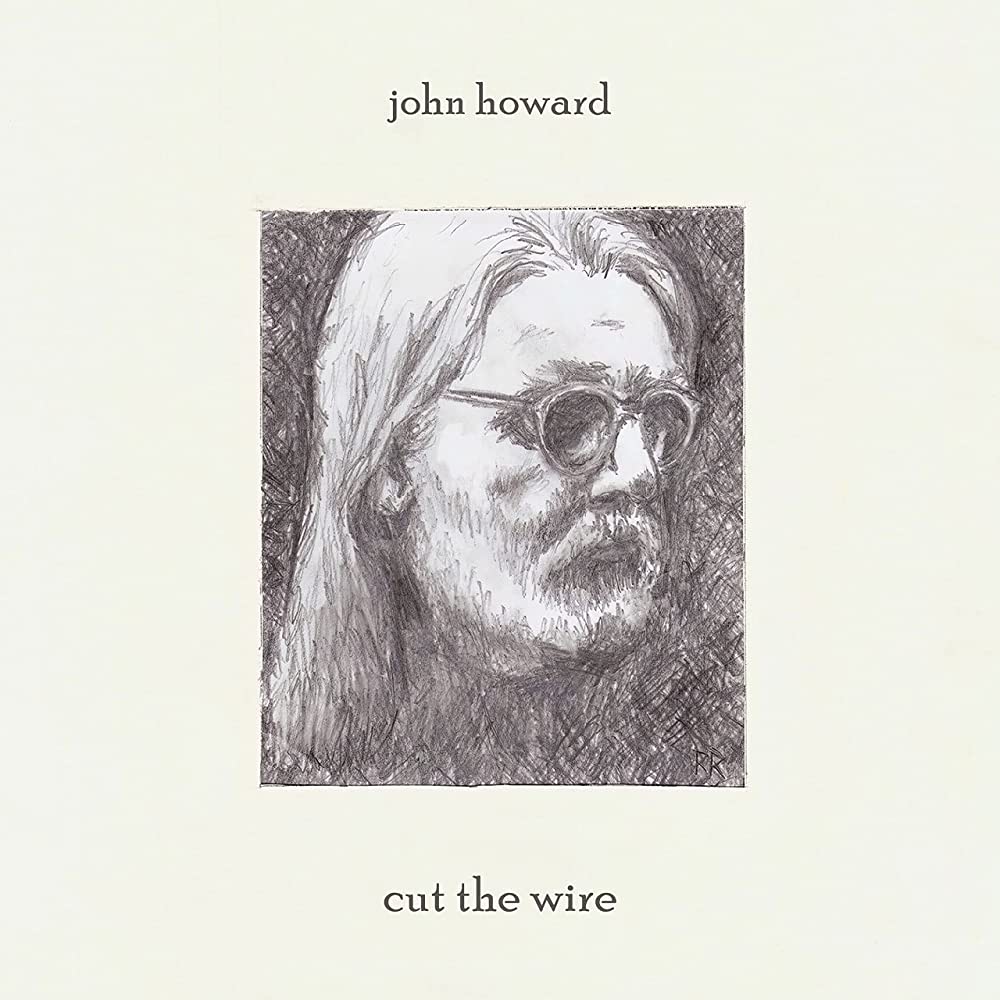

Think Like A Key Music recently released his 2019 album on vinyl. ‘Cut The Wire’, originally released on Spain’s You Are The Cosmos label, was written and recorded by Howard at his Una Casita studio in Murcia after working on his first autobiography, Incidents Crowded With Life. It was a creative process whose influence can be clearly heard on these new compositions.

“Writing songs feels like teamwork with an unknown entity”

Where does your love for piano originate from? What would you say were some of the early influences and do you feel those influences changed as you gradually became better at it?

John Howard: My father was a pianist, he played in several jazz bands around the North of England when I was growing up, and I used to love hearing him routining songs for his band to play on the upright piano in our sitting-room. I began trying to play the piano at about four or five years old. My dad remarked to my mum that I was playing with two hands naturally, and decided to send me for piano lessons, which I began when I was seven years old and continued until I was sixteen.

Dad had a record by Dave Brubeck, Take Five, and I really was intrigued by the odd time-signature – 5/4 – and wanted to know more about it, asking my dad to show me on the piano. Other pianists my dad listened to were Peter Nero and Roy Budd, who also had a great sound of their own, different techniques and to me fascinating. I loved their chords, they were intriguing, and again would ask my dad to show me how to play them. So I had quite a jazz influence from an early age, coupled with my classical training.

Interesting, unusual chord and chord structures always fascinated me. I remember the first time I played Eb major seventh, quite by accident, my hands simply played it as I was doodling on the piano. I thought it sounded so strange and yet rather beautiful, just lowering the top E flat of the right hand chords to a D and you had this great sound. I think that’s when I began loving harmonies too, how changing just one note in a chord could give it a whole different shape and sound, and you could move through a chord with tiny alterations.

Although I was classically trained and obviously could read music, it was the shapes of chords, the shapes my hands made when I played them, which fascinated me more than the dots on a piece of sheet music. But having a classical training definitely gave me an important grounding to how my playing emerged and developed, it increased my understanding of what you could do in a piece of music, how you could alter the mood of something, creating different visual images, and various emotions for the listener.

When I was about ten, in 1963, the British pop scene changed radically, with artists writing their own songs, as well as a new generation of songwriters emerging alongside with great, unusual styles and lyrics. There was a whole different sound filling the pop charts. Pianist/songwriters like Burt Bacharach and his odd time signatures and Bossa Nova rhythms, Randy Newman with his wonderful evocative lyrics and gorgeous chord structures, and the interpretations of those writers’ songs by Dusty Springfield, Sandie Shaw, Cilla Black, Dionne Warwick, Gene Pitney, all bringing out three-minute pop operas, “Drama Pop” as I call it. The King of that genre of course was Roy Orbison who wrote some wonderful songs, sung with that amazing voice of his which sounded like something the angels had sent.

And the sound of Phil Spector! Its density and depth. It influenced Brian Wilson, The Walker Brothers, Dusty and Sonny & Cher, who created great records using the same Wall of Sound technique, drenched in reverb. It all had a huge effect on me, the sound of records as much as the songs themselves.

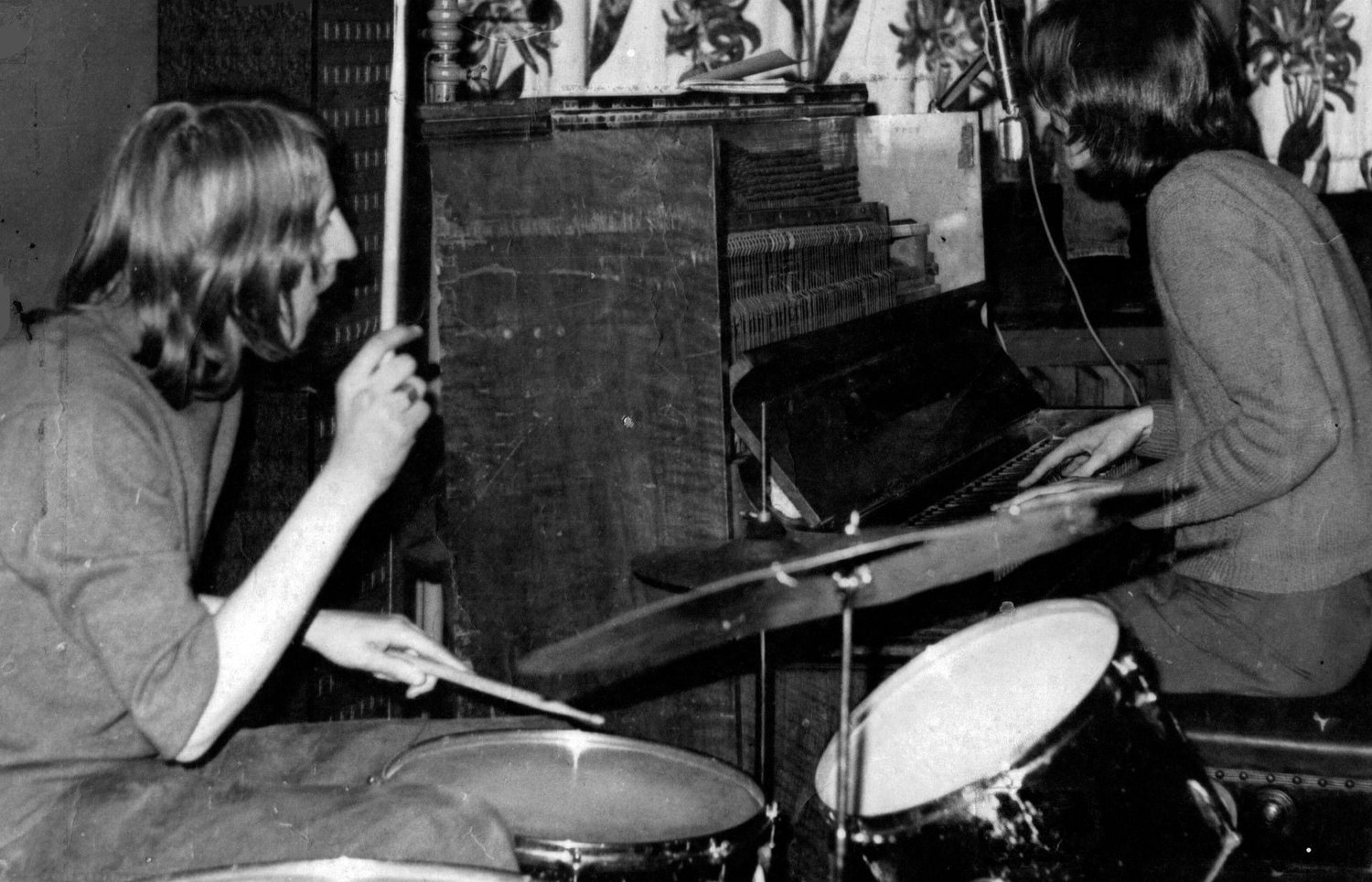

By the age of twelve I was beginning to write my own songs, inspired by the records in the charts, and having the piano as my natural accompaniment made it easier to create unusual chords and structures. By the age of fifteen I was starting to record my songs on a tape recorder which my parents bought me, experimenting with double-tracking, harmonies and overdubbing instrumentation and percussion.

Tell us about your upbringing?

It was a happy childhood, though always with the Roman Catholic faith at its heart. I had several aunts and cousins who were quite religious. My father being Church of England and something of an agnostic helped balance things, but I was quite a devout kid and only began to question the whole thing of God and Faith when I reached my teens, it started to make no sense to me and was incredibly judgemental.

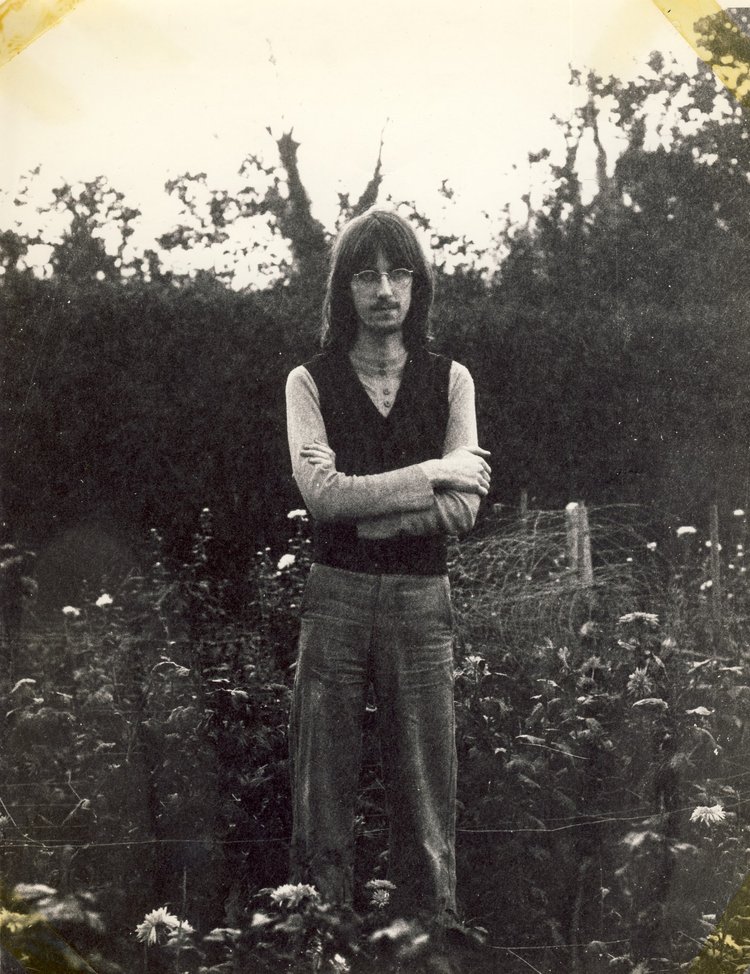

I grew up on a council estate in Heywood, Lancs, an old cotton mill town where my maternal grandmother and her sisters had worked from the age of fourteen. We had lots of countryside around us, and would spend most of our weekends by the brook across the road or running around the fields behind our house. My dad had a garden full of various vegetables and salad stuff and most summers my sister and I would help him “pod the peas”, or pick the strawberries and raspberries. I have only good memories of my time there.

We moved from the council house to a newbuild semi-detached in Bury in 1960, as my mum wanted her and dad to own their own home. Although the house was great, full of ’60s mod cons which my mum loved, I wasn’t happy at my new school. I had a slightly different accent – “posh” the other kids called me – and I found my classmates rough, many of them from poor backgrounds and made me feel alienated from them. I didn’t have a problem with them, not when I first arrived anyway, it was the other way round. They refused to accept me. Of course, I was bullied. I was considered different, and therefore a target.

It was a terrible building too. I’d left my school in Heywood, a brand new modern place set in fields as far as the eye could see, and had been moved to a completely dilapidated, draughty Victorian building, freezing cold in the winter, with awful outside toilets, in one of the roughest areas of Bury. Quite often, bits of the ceiling would fall down and land at our feet as we were studying. How no kid ever got hurt I don’t know.

It wasn’t until I started at the local secondary modern school (I failed my 11-plus exams), a recently-built more comfortable place, that things gradually improved. I discovered I had a talent for performing and usually got picked to play a part in one of the annual school plays. When my teachers found out I could play the piano, I was asked to play in the assembly hall occasionally, even ending up performing Beatles songs at one of the school’s Christmas parties.

That was when I realised I loved being a performer, especially singing and playing to a captive audience. It felt great! I also learnt that by being different in a more “unique” way, “someone with talent”, I found a new acceptance, even an admiration from my fellow pupils. Life at school became more tolerable and my path forward was set.

Do you recall some of the first records you bought? What about radio? Did you stay up awake at night listening to pirate radio stations to hear exciting sounds?

The first single I bought was Elvis Presley’s ‘It’s Now Or Never’ in 1960 when I was seven. It was his name on the label I liked when I was flicking through the record store in Bury Market, while my mum was across the aisle at the greengrocer’s stall. Mum gave me the money to buy it. When I put the record on our radiogram at home, I couldn’t believe this guy’s voice. He sounded almost operatic at times, and so powerful. I had no idea who he was at that point but I certainly became a fan.

My sister bought a couple of John Leyton singles, ‘Son This Is She’ and ‘Johnny Remember Me’, around ’61 and ’62. I didn’t know who the producer was, but I loved the sound, with those way-off-in-the-distance female backing vocals, and a kind of bathroom echo throughout. One of the “B” sides was called ‘Six White Horses’, which sounded so otherworldly to me, creating images in my head of Tony Curtis and Charlton Heston aboard their “golden chariot”. It wasn’t until a few years later that I found out the records’ producer was Joe Meek, and was fascinated to learn how he recorded many of his singles in his bathroom at home!

I think the first record I bought with my own pocket money was P.J. Proby’s ‘Hold Me’. That would have been in 1964. Again, it was his voice I loved when I saw him performing the song on the pop show Thank Your Lucky Stars. He looked so exotic and with that brilliant self-harmonising he did, I think he became my first pop crush!

After that I started to spend all my pocket money on singles. I’d watch shows like Ready, Steady, Go! and Top of The Pops each week and decide which hit I was buying, whether it was Dusty’s ‘I Just Don’t Know What To Do With Myself’, Cilla Black’s ‘You’re My World’, Gene Pitney’s ‘That Girl Belongs To Yesterday’ featuring Gene’s brilliant self-harmonising, or The Rolling Stones’ ‘It’s All Over Now’ with its fabulously echoed guitar sound.

My sister was buying mainly Beatles records by then (having ditched Cliff Richard, her previous “pop-pash”, for Paul McCartney) but I beat her to the record store when The Beatles’ ‘I Feel Fine’ came out in November ‘64. Wow! What a sound, their biggest so far. Crystal clear, pristine double-tracked harmonies by John and Paul, great chorus, and that opening feedbacked guitar!

I used to listen to Radio Luxembourg in the evening, it played some fabulous records, although the signal kept fading in and out. Then of course, Radio Caroline came along and they played records you didn’t hear anywhere else. I think that’s where I first heard records like The Byrds’ ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’, Sonny & Cher’s ‘I Got You Babe’, Lovin’ Spoonful’s ‘Summer In The City’, The Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’, Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Purple Haze’, Procol Harum’s ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ and Pink Floyd’s ‘See Emily Play’. Those productions blew me away, sounding like they came from another planet, all so new and different, revolutionary, pushing the boundaries of sound and lyrics.

I was becoming a huge Beatles fan by ‘67, buying ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ / ‘Penny Lane’ after I’d heard a snippet of both sides on a BBC show called Juke Box Jury. I bought everything by them after that single, ‘Sgt Pepper’ in particular blowing my mind. It was great to be fourteen years old in 1967!

How would you describe the folk scene back then?

I wasn’t particularly a folk music fan until later in my teens, my tastes were all about pop music, what was the latest single in the charts. But I do recall the first time I heard Dylan’s ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ in 1965, probably on Radio Caroline, and loving it. It sounded like nothing I’d heard before, a musical whirlwind of vitriol, driving instrumentation and that ghostly organ swirling around.

I’d only been mildly aware of Bob’s Folk/Protest period, a friend at school loving ‘The Times They Are A-Changing’, which, to be honest, sounded to me like a really old guy singing! But ‘Rolling Stone’ was another ball game entirely! Dylan sounded incredible! A huge record for both Folk and Pop, astonishing pop fans and enraging Dylan’s folk followers. The first Rock record really. I loved its lyrics too. It was incredibly mean and judgemental in many ways, not at all the kind of thing one heard on pop radio in ’65, but so beautifully constructed, powerful and astonishingly delivered. Bob virtually spat out the line “How does it fe-e-e-el?!”, and singing in that ‘out-of-tune-but-in-tune’ way he’d developed by then, sliding up to notes and using his voice more as an instrument, an extra sound and texture, as opposed to being a perfectly in tune vocalist fronting a band. So many other artists have copied it over the years – Ian Hunter and Steve Harley to name just two.

It was when I heard a track by Roy Harper in late 1969 on the art college record player, one of those CBS sampler LPs, that I fell in love with the sound of a solo singer with just an acoustic guitar. I went to see Roy in Manchester a few weeks afterwards and fell in love with him, dashed to my record shop the next day and bought his just-released new LP, ‘Flat Baroque and Berserk’, still one of my favourite albums. I also heard Joni Mitchell’s first LP around that time too, at a friend’s house, falling in love with her voice and guitar technique, and bought her second one, ‘Clouds’. Beautiful album.

I remember being really impressed when I first heard Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Bookends’ album, around the time ‘Mrs Robinson’ came out. A school friend of mine was a big fan of theirs and used to try to turn me onto them, but I’d always found their albums a bit too sweet and sugary, extremely pretty LPs but lacking for me in substance sonically. It was Bookends which had that extra bite, a brilliant production and clever arrangements and Paul Simon’s voice had never sounded better. It’s one of the albums I still go back to and listen to all the way through, there isn’t a duff track on there.

In early 1970 I saw The Incredible String Band in Manchester and oh my word, they were fantastic. So joyous and multi-talented. The concert was like being at a fabulous hip party with a theatre-full of groovy people having a ball. I bought several of their LPs over the years.

I also got into Laura Nyro around that time. What a genius she was. I bought ‘Christmas and The Beads of Sweat’ because I loved the cover, but oh my, when I got it home, I was blown away. Her piano playing, the arrangements, and her voice. It was gentle as a lamb one minute and the next she was almost screaming as a brass section wailed away and her playing became frantic, then suddenly, everything was quiet and intimate again. Some friends of mine found her too much, too unpredictable, but I loved the verge of craziness which she achieved on her songs. And of course Leonard Cohen. I bought his first four albums and still adore each one. Poetry set to music.

A college friend introduced me to The Mothers of Invention and took me to see them in 1971, when Flo & Eddie were on backing vocals. What a concert! Zappa conducted everything by jumping up in the air and, as soon as he landed, the band would go into a different section.

I’d gone from buying singles to LPs by the late ‘60s, perfect timing really as “albums artists” were becoming “the thing” and that whole singer-songwriter boom was beginning. The BBC had just started their In Concert series featuring solo artists accompanying themselves on piano or guitar, and I watched each one, dreaming of the day when I might be featured on there.

British pop music had become a little staid by 1970, too many MOR singles hogging the charts for my taste, but then in late 1970, T. Rex arrived, well basically exploded onto the pop scene, changing the look and sound of pop music forever and inventing Glam Rock.

“T. Rex were the new Beatles”

Marc Bolan had been a folk-styled artist with Tyrannosaurus Rex, and was doing okay and building a strong hippie following with albums like ‘Unicorn’ in 1969 and ‘Beard of Stars’, which I bought in the Summer of 1970. (If you listen to the track ‘Fist Heart, Mighty Dawn Dart’, you can hear the blueprint for what became the sound of Adam & The Ants).

But with T. Rex, Marc completely reinvented himself, with ‘Ride A White Swan’ and then in 1971 ‘Get It On’ and the album ‘Electric Warrior’. T. Rex were the new Beatles. I saw Marc performing with Micky Finn in Blackburn just after ‘Ride A White Swan’ had been released. The hippies began storming out of the concert hall in droves once he picked up an electric guitar, all shouting “Traitor!”, while his new teenage fans rushed to the front of the stage and screamed their heads off for the rest of the evening. It was one of those magical moments in pop music. Similar I guess to when Dylan “went electric” in ’66.

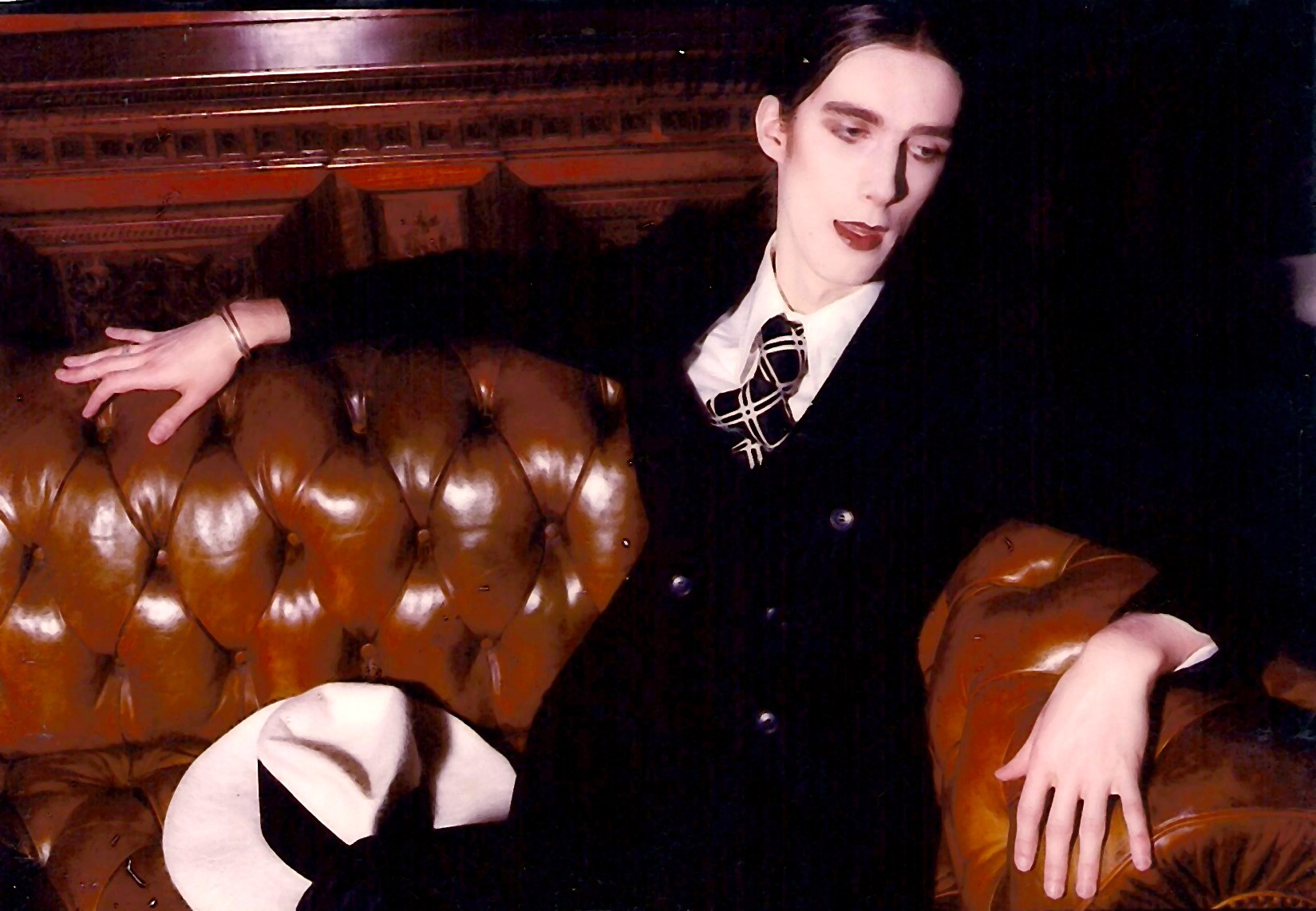

Without Marc Bolan there’d have been no Glam Rock, there’d have been no ‘Ziggy Stardust’, there’d have been no androgynous pop stars stomping up the charts in sequins, satin and sparkly platform boots. By 1973, the T. Rex rollercoaster ride was coming to an end. Bolan had strangely lost the capacity to progress musically, each single sounding like the last one. But meanwhile, bands like Wizzard, Slade, Mott The Hoople, The Sweet, and artists like Gary Glitter and David Bowie, were storming the charts. They all have Marc Bolan to thank for their short but huge hit-making Glam Rock period, with one exception – only Bowie had the wherewithal, creativity, talent and nous to keep coming up with new images, new sounds and new personas. He transcended Glam and, like a chameleon, never stopped making the ch-ch-ch-ch-changes.

You played several times with Spirogyra. I interviewed Martin Cockerham before he sadly passed. How do you remember those gigs?

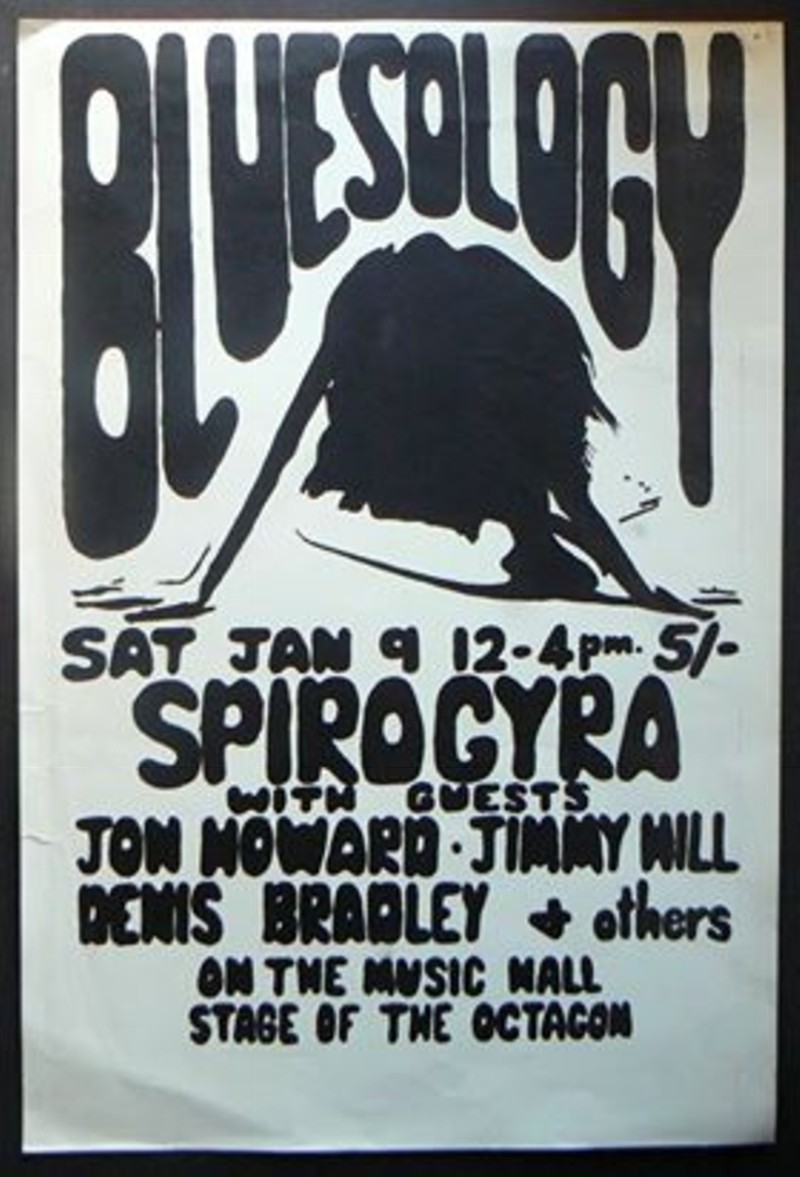

Spirogyra were such a great band on stage and Martin was a really lovely talented man. I thought they were going to be huge. I first shared a concert bill with them in September 1970 at The Octagon Theatre in Bolton. They were amazing, and their sound engineer was a genius, giving them a massive sound which literally roared around the theatre. I think Martin was from Bolton but the group had met at Canterbury University. So he was “the local hero made good” in many ways whenever he appeared at The Octagon. I bought their first LP, ‘St Radigunds’, a few months later, and while it was an excellent album, it didn’t capture the excitement and the sonic hugeness I’d experienced at that first gig with them.

We performed on the same bill again in January 1971 at The Octagon, though it was a strange show as all the artists were separated into little “rooms”, and the audience just wandered by, stayed for a few minutes listening to you, like you were part of an exhibition, and then going onto the next “room” where “another exhibit” was performing. It was a terrible idea, whoever came up with it. It meant you couldn’t build up an atmosphere with an audience

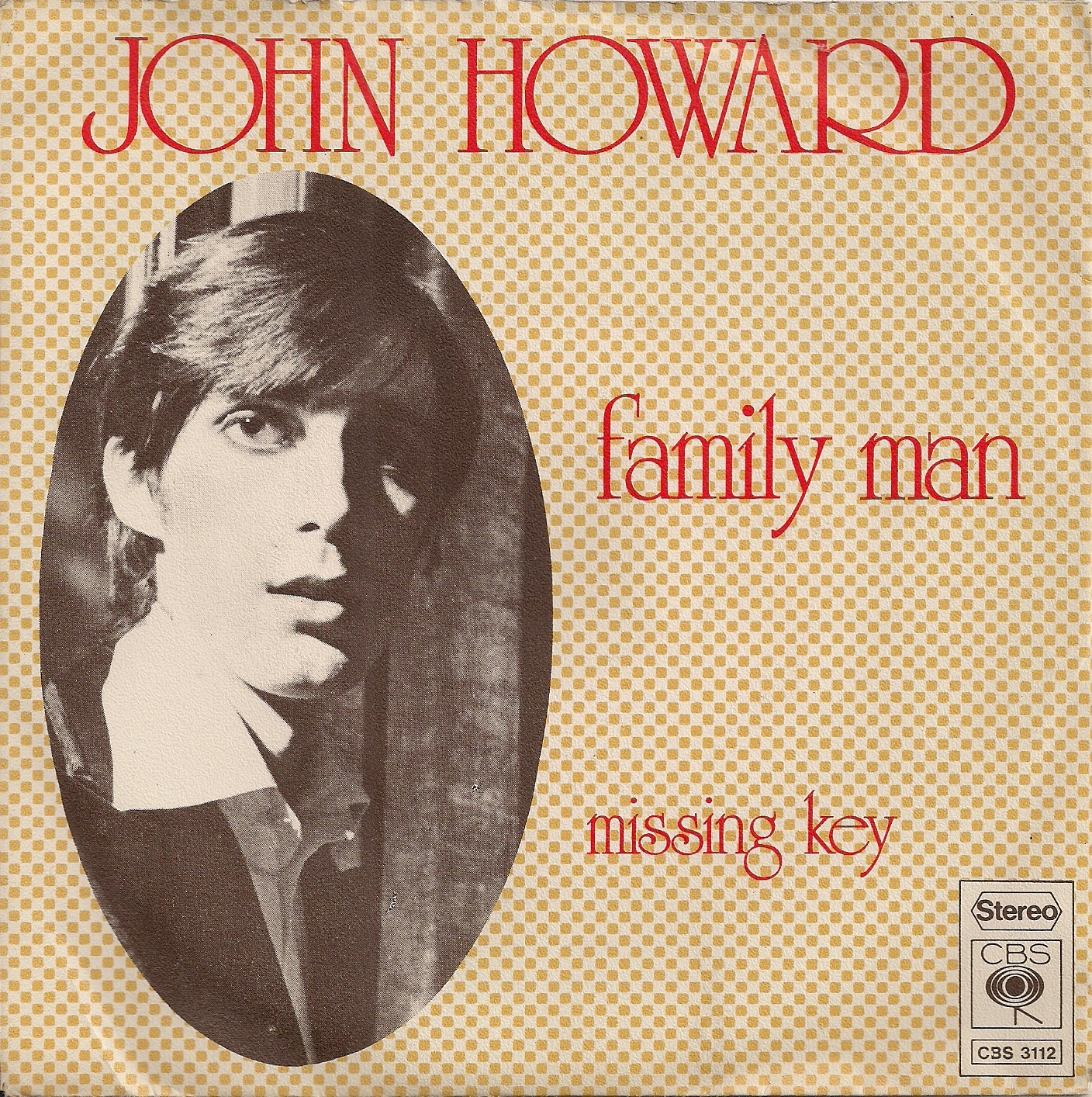

In December that year Spirogyra’s manager Max Hole asked me to be their support act at their Christmas concert at The Octagon. It was a brilliant evening, the place was packed, the atmosphere was fantastic, and I remember I’d just written ‘Family Man’ and performed it that night for the first time. It went down well and became one of my “keepers” for the future.

I was the band’s support once more in February 1973, again at The Octagon. I think they were beginning to split by then, so the atmosphere wasn’t quite so elated as it had been, but it was still a lovely evening. I was also thinking of leaving home to try my luck in London, so it felt a bit “end of the line” for me.

Of course, Barbara Gaskin enjoyed her own chart success with Dave Stewart in 1981 with her cover of ‘It’s My Party’, which was a million miles away from the music she made with Spirogyra.

I actually got back in contact with Martin on Facebook in around 2016, I think. I can’t recall who contacted who now, and why, but we exchanged a few messages over the next year or so and he seemed happy and positive about things. It was a shock when he died in 2018.

The band’s manager in the early ‘70s, Max Hole, became A&R Director at Warner Bros in the ‘80s, discovering and signing one Howard Jones, which was ironic as that was my birth name before I changed it to John Howard in 1970! Last time I heard about Max, he was Head Honcho at Universal Music.

Looking from today’s perspective those were really different, special times for being a musician, weren’t they?

I think so, yes, though I am a little biased, I guess! There weren’t so many artists around then releasing music for one. You basically had to go to London to get a record deal, and you had to have a record deal to get on the radio and possibly achieve success. It was harder to get noticed and signed back then, there weren’t all the TV talent shows there are now, and routes like YouTube, Instagram and TikTok, which can help break an artist to a very wide public, none of that existed. Back then you just did your thing, gigged as much as you could – and there were loads of folk clubs and Unis to play at – and stayed hopeful that someone would see you who could help get you on the ladder.

The live scene was amazing at that time, when I was just starting out. People loved coming out to gigs, even if they didn’t know any of the artists who were playing. There was a sense that audiences were keen to hear what you had to offer, and really listened. It was a slow burn, every time I played somewhere I gained a few new fans who made the effort to get on a bus and come to see me at my next gig.

My dream was simply to write songs, make LPs, perform at great venues and have an increasingly larger following. Chart success never entered my mind. I assumed I’d be successful, in that youthful, rather arrogant way, but success to me meant having an audience who loved what I did and would fill a concert hall wherever I played. I don’t think I ever saw myself as “a pop star”. I guess, in my head, I was “the new Roy Harper”

I’m glad I’m not a young artist starting out now. It’s all about streaming figures now, YouTube views, social media connections. You can have a huge amount of streams, in the millions, but still not have a record deal, or even the opportunity to make an album. Albums are almost ‘old hat’ now, it’s just about the next track you put on Spotify, then you have to promote it like mad on social media, plus at any gigs you can get (though it’s unlikely “talent scouts” will be there now, record companies just keep an eye on who’s getting the most streams).

There doesn’t seem to be any long term career plan, no-one having your back, it’s all very DIY and “bitty”. I feel sorry for the kids who are having to navigate such a landscape now. There’s so much young talent around, and I often think “Why isn’t that artist a huge star?”. It feels out of kilter. Some of the new artists get deals with a label then sit at home waiting for something to happen. I’d hate it, that sense of having no direction, no signs along the road.

How did you get signed to a major label like CBS?

Pure chance really but none of it plain sailing. I was sharing a flat in Kilburn in the Autumn of ’73 with about five other people, and one of them was a guy called Brian Keith. He’d been lead singer in Plastic Penny who’d had a hit in 1968 with ‘Everything I Am’, and then he had a hit in 1971 with The Congregation – ‘Softly Whispering I Love You’.

He introduced me to Stuart Reid, who was then Head of Pop at Chappell’s Music Publishers. I invited Stuart and his wife Patsy to see me perform at The Troubadour in Earl’s Court, they came along, loved what I did and literally the next day, Stuart took me for lunch and signed me to a management deal. He put me in Chappell’s studios below his office in Hanover Square where I recorded several demos over the next few nights, some solo, some with Eddy Pumer’s band. Stuart put them on a demo tape and took it to several record companies.

Jonathan King, who ran UK Records then (10cc were with the label at that time) was keen to sign me, but only for one single. He loved ‘Family Man’ and thought it had the potential to be a big hit. However, Stuart had much bigger plans for me, and eventually got a great reaction from CBS. Their A&R Director Dan Loggins (brother of Kenny Loggins) and A&R Manager Paul Phillips came to see me perform at a small club called Small’s in Knightsbridge, and it was all looking very positive ,lots of handshakes and chatting after my show, then things went quiet.

Then in around mid-November, someone from the company called Stuart and said they wanted to change my name. They didn’t like “John” and instead wanted to rename me Christopher Howard. I refused and Stuart agreed with me, letting CBS know it was John Howard or nothing. For the next couple of weeks, it looked like it was going to be nothing.

But in early December, a friend of Stuart’s, the film director Peter Collinson who had done Up The Junction and The Italian Job, ran into him in Oxford Street. He told Stuart he was looking for a song for his next movie, Open Season starring Peter Fonda and William Holden, and agreed to listen to some of my demos. Stuart biked a tape over to Peter’s house, got a phone call the next day from a very enthusiastic Mr. Collinson, who told Stuart he wanted me to write the theme song for his movie.

We were invited to go to Madrid just after Christmas to see the rushes of the film, and within a couple of days of getting back to London, I’d written two songs, ‘Missing Key’ and ‘Casting Shadows’. I went into Chappell’s to record demos of the songs, Stuart sent the tape to Peter and by the end of the year, I’d been commissioned to record both songs for the movie in Rome in early January.

In the New Year, Stuart called CBS to let them know about my film commission and who was directing and starring in the movie. The following day, he got a call back from the label. They said they definitely wanted me on CBS and asked him to go into their office in New Oxford Street to discuss the deal. By the second week of January, I was signed to CBS and on my way to Rome to record ‘Casting Shadows’ (‘Missing Key’ having been taken out of the equation as Peter wanted the one song to start and end his film). I felt I was finally on my way!

How did your repertoire look before recording your debut album?

The songs which eventually made up ‘Kid In A Big World’ were picked by the album’s producer Tony Meehan. Stuart had given him a tape of about twenty demos I’d recorded since Autumn ‘73, and Tony chose ten of them. Nine of them are what you see on the album now, but there was a tenth song, ‘Third Man’ which was originally meant to close the LP. It was beaten to the punch by a new song I’d written just a couple of days before the sessions at Abbey Road began: ‘Gone Away’. As soon as Tony heard it, he made a quick recording of it on his Dictaphone, told me it would replace ‘Third Man’ on our planned track listing and went away to write the arrangement.

When was most of the album written and what would you say were some of the main inspirations for the tracks.

Most of the songs, apart from ‘Family Man’, were written between 1973 and early ’74. Inspirations covered a wide variety of artists, The Beatles, Bowie, Roxy Music, Noel Coward, Gilbert O’Sullivan, Joni Mitchell, Laura Nyro, Dave Brubeck, Jacques Brel. The ’73 compositions were mainly written on my parents’ clapped-out old upright piano in Lancashire before I left home for London, songs like ‘Maybe Someday in Miami’ (inspired by Roxy Music), ‘Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner’ (Noel Coward being my muse there), and ‘Kid In A Big World’ (with Jacques Brel and Edith Piaf in mind).

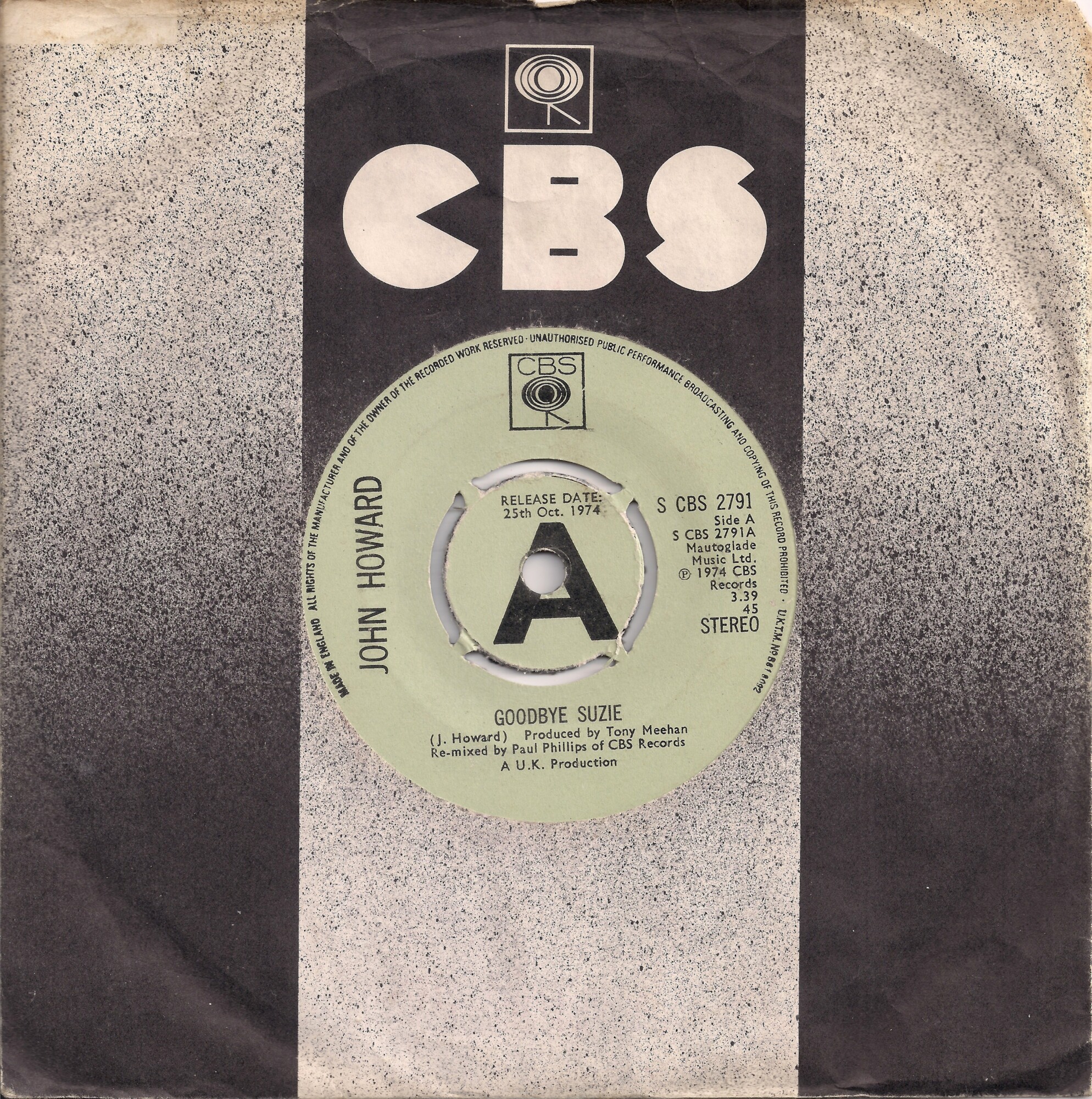

‘Goodbye Suzie’ (which I suppose was influenced by Bowie’s ‘Life On Mars’) was written one evening in October at Stuart’s office on his beautiful white grand piano. ‘Missing Key’ was written for Open Season in December on the same piano, while ‘The Flame’ (Lennon & McCartney touches there), ‘Gone Away,’ (originally a Bacharach/Carole King-inspired song before Tony slowed it down to a more McCartney-esque feel), ‘Spellbound’ (the jazz influences coming through) and ‘Deadly Nightshade’ (Gilbert O’Sullivan inspired that one) I wrote on The Reid’s piano at their house in Willesden Green in early ’74.I used to go there each morning for breakfast with Patsy and then spend the day writing.

Tony was very keen that we made an album which showed many styles, “like a Beatles album, John,” so he gave ‘Miami’ a 1930s Palm Court vibe with Harry Gold’s Orchestra backing me, he turned the Coward-esque ‘Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner’ into a more Gothic/Marvel Comics creation, ‘Deadly Nightshade’ became a brass-backed Swing number, and ‘Missing Key’ lost its decorative piano motif that I’d played on the demo, becoming more a ‘Golden Slumbers’ type number.

“Most of the album was recorded at Abbey Road”

The album was recorded at Abbey Road. Please share your recollections of the sessions. What kind of equipment did you use and who was the producer? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

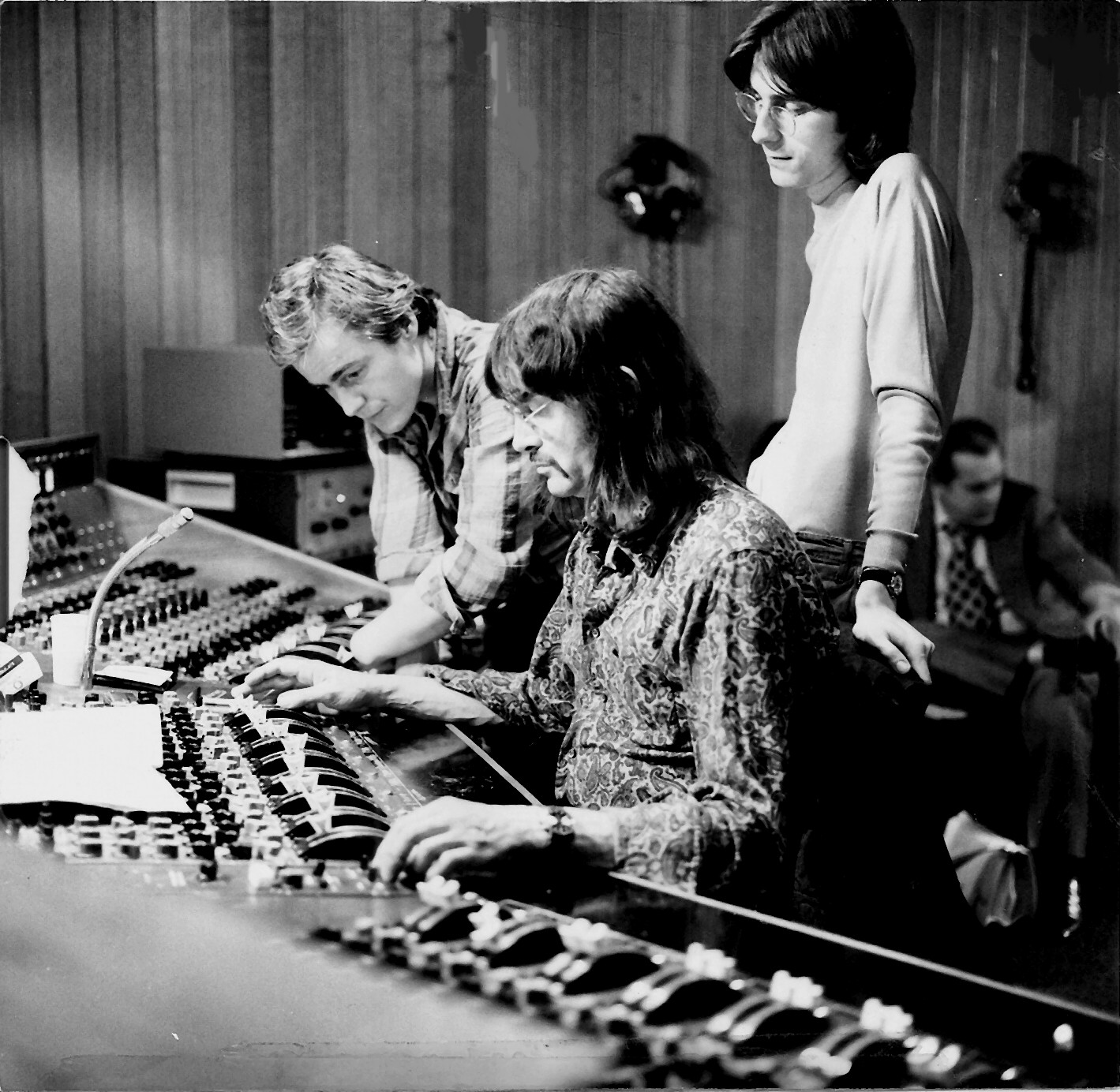

Most of the album was recorded at Abbey Road on their 16-track desk, between April and July ’74, and two tracks were redone in September at Apple Studios…more about that later! Obviously, for a young artist to be making his debut LP at the recording home of The Beatles was, for me, a dream come true. To look out of the control room window and see that famous steep staircase down into the massive Studio 2 was almost like an apparition the first time I saw it.

The engineer was Peter Bown, who’d worked with The Hollies, Gerry & The Pacemakers, Cilla Black and Pink Floyd. George Martin had once referred to him as “an electronics wizard”. He also engineered the Phil Spector ‘Let It Be’ overdubs. Such a lovely guy, always dressed in one of his many paisley shirts, which were his trademark gear, and very honest about one’s performance. He’d never offer an opinion unless asked, but if I or Tony said, “What do you think, Peter?” you’d get a truthful answer, whether you liked it or not!

My memories of the actual sessions are a bit mixed. On the one hand, my producer Tony Meehan was great to work with, a very musical guy with lots of ideas for my songs. But on the other, he quickly began disagreeing with my manager, Stuart, who attended every session and stayed often all day, much to Tony’s displeasure.

Tony had decided that quite a few of the songs needed major changes from the demos Stuart had played for him. Although I’d had no warning of that, I was happy to spend time sitting at the Studio 2 grand piano basically relearning my songs to fit how Tony saw them. He’d stand with me as I played and tell me to “drop that piano motif” on ‘Missing Key’; “forget the rallentandos into the choruses of ‘Goodbye Suzie’, too theatrical, John,”; “less twiddly bits, John, keep your piano playing simple to give the backings room to breathe.”

Stuart was astonished that we were spending so much time changing the very structure and style of the songs. The biggest beef he had was how Tony had decided to slow down ‘Gone Away’ from its original Bacharach ‘Walk On By’ rhythm to more than half the speed it had been. It sounded interesting when I began to get what he wanted me to play, but I told him the song was pitched very high and I was finding it hard to sing in such a slowed down state.

“John can’t sing it, so slowed down, Tony!” Stuart protested.

“Don’t worry, Stuart, we’ll sort that out at the vocal session,” Tony replied, trying to stay calm and pleasant. “This is a recording session, Stuart, not a live performance.”

I got to overdub mellotron on ‘Gone Away’, the same mellotron The Beatles had used on ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, Tony told me in my cans as I sat down to play the overdub. The harpsichord and strings on that track are me on the mellotron.

Tony also wanted the songs ‘Kid In A Big World’ and ‘Maybe Someday In Miami’ to have a 1930s Palm Court Orchestra backing, not featuring me on piano at all. Harry Gold, the legendary bandleader from the Swing era, had written new arrangements and brought in his musicians to recreate the sound of the old Big Band 78s.

‘Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner’, which Stuart always saw as my Noel Coward number, became more a Gothic/Marvel Comics feast of sound effects, Rod Argent coming into add guns shooting, Moog sounds flying around and me on electric piano rather than the Grand piano. Tony also asked me to change my vocal phrasing on the choruses, elongate my words.

Instead of the slightly arch-clipped delivery, he wanted more of a rock singer style.

I regularly saw Tony and Stuart having words up in the control room as we completed another take, Tony obviously trying to explain to my manager what he had in mind and Stuart waving his arms about, clearly not happy.

Then it came to the vocal overdubs. Again, Tony wanted me to change the way I sang some of the songs, “don’t hold the note on so long,” “make it more Pop”, and stuff like that. It meant once again relearning my technique, this time my approach at the mike. I knew these songs inside out before the sessions began, I’d been performing them for months in various clubs, but some of them had become like unknown compositions. I had to find different ways of singing. Every time I made a mistake at the mike, or stopped and asked if I could do a line again, Stuart would leap out of his seat and stare through the control window at me looking horror-struck, followed by Tony striding towards him and telling him to sit down.

‘Gone Away’ was the most challenging track. When it became clear I found it impossible to sing the song all the way through without making a mistake or my voice cracking, Tony suggested we take it in sections. “We’ll get the verses right first, then we’ll move onto the choruses, and perfect those.”

As with everything Tony suggested, although it had been a challenge to get it right, his ideas were brilliant, and once everything fell into place the tracks sounded great. He’d wanted to take me out of my comfort zone and push me to try new things, new approaches. But Stuart couldn’t understand why I hadn’t been allowed to record my songs as they’d been written.

“We’re recording an album to show John off to his maximum potential and full force,” Tony replied, adding rather pointedly, “This is not a series of demos!”

The only recording at Abbey Road I never liked – agreeing with Stuart on this one – was ‘Kid In A Big World’. Harry Gold’s 1930s arrangement was lovely, but it simply wasn’t the song I’d written and I felt it destroyed the intimacy I’d had originally. Tony wanted me to sing it live with the band and kept pushing me during the recording to make my vocal “more BBC British”, “imagine you’re a crooner in the ‘30s in a swish club”, “get really posh!”, etc. I felt very uncomfortable, it seemed completely false to me, and took away the drama of the song. In the end, on about the fourth take, Tony said, “That’s fine, John, let’s do ‘Maybe Someday In Miami now.”

That recording worked better, I still managed to camp it up as I had on the demo, though the Roxy Music vibe I’d intended when I wrote it had gone. But as a track, it works fine, Harry’s band really swung.

When Stuart had delivered the album to CBS in July, there was an initial muted response, and it wasn’t until I attended the CBS annual sales conference in Eastbourne in August that people began telling me how much they loved the album, ‘Goodbye Suze’ especially getting a big thumbs-up from everyone when the album was showcased for the sales force and American management.

However, over breakfast with my A&R Manager, Paul Phillips, he revealed that he wanted to re-record the songs ‘Family Man’ and ‘Kid In A Big World’, to bring them back to how they sounded on my original demos.

“Thank Christ for that!”, Stuart shouted, almost hugging Paul.

“We’re going to record them at Apple Studios, John,” Paul continued, “so you will have made your album at both Beatles studios!”

Those sessions were much happier ones. Stuart got on with Paul really well. Once again, I got to work with a former Beatles engineer, this time Phil McDonald, who’d worked on ‘The White Album’, Lennon’s ‘Instant Karma’ and the ‘Imagine’ album.

Stuart smiled from start to finish, and it did feel great recording ‘Kid In A Big World’ at the beautiful new Grand piano in the recently refurbished studio in Savile Row. I sang and played at the same time as Paul wanted a really intimate performance, and it was take two of three he picked. Then he overdubbed a lovely strings backing he’d arranged and Pete Zorn played a beautiful sax solo.

After we’d finished ‘Family Man’, we also recorded ‘Third Man’ for the ‘B’ side of the first single, ‘Goodbye Suzie’, which Paul had remixed as he felt Tony hadn’t mixed my piano up enough and wanted more of my vocal in the mix.

Tony was rather mortified when I played him the Apple tracks, but I was actually relieved that the Harry Gold ‘Kid In A Big World’ had been replaced and, though the Abbey Road ‘Family Man’ was fun, with lots of Rod Argent’s Moog zooming all over it, Paul Phillips’ production sounded much more commercial and in fact became my second single. Mike Batt visited the session and declared ‘Family Man’ was a surefire hit, and even Dan Loggins popped in, telling everyone how great Paul’s productions sounded. So everyone – apart from Tony – was happy at last.

Who were other musicians on the album?

On the released Abbey Road recordings, the drummer was Bob Henrit and the bass player was Dave Wintour, though I can’t recall who the guitarist was now. There was also a brass section which overdubbed great jazz-inspired parts on ‘Spellbound’, a Motown-esque arrangement on ‘Deadly Nightshade’, a solo sax part on ‘The Flame’ and a lovely riff Tony actually sang to the guys in the choruses of ‘Goodbye Suzie’. Rod Argent too of course did work on ‘Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner’ and Harry Gold and his orchestra backed me on ‘Maybe Someday In Miami’.

The Apple sessions players were Pete Zorn on bass, flute and alto sax, the drummer was Barry De Souza and the acoustic guitars were played by a CBS duo, Nicol & Marsh who Paul was producing at the time.

Did the record receive any airplay?

In a word, no. Well, ‘Goodbye Suzie’ got quite a few plays on Radio Luxembourg. It actually reached the Fab208 Powerplay Top 30 for a couple of weeks. But Radio 1 and 2 refused to play anything, the Playlist Committee declaring ‘Goodbye Suzie’ as “too depressing for our audience” and ‘Family Man’ as “anti-female.” Their reactions were quite bizarre, and rather ironic as earlier in ’74 I’d performed a live session for Radio 1, which included ‘Goodbye Suzie’. The station had no problem playing the song then, in fact the DJ, who I think was David Hamilton, raved about the song. The lack of airplay sank the two singles and as a result the album too. Within a few weeks of ‘Kid In A Big World’ being released, it was as though it had never happened. No-one at CBS nor my management ever mentioned it again.

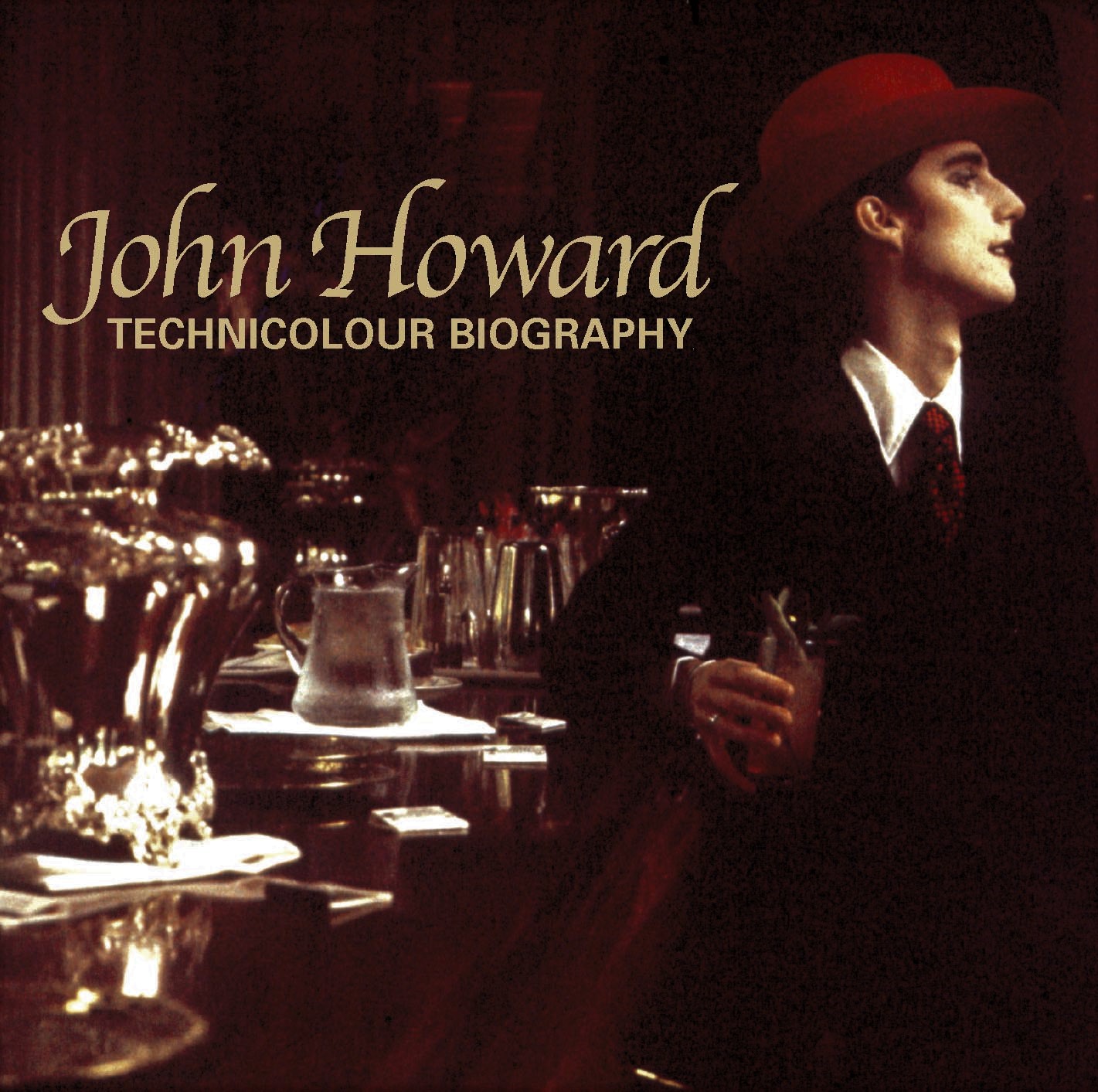

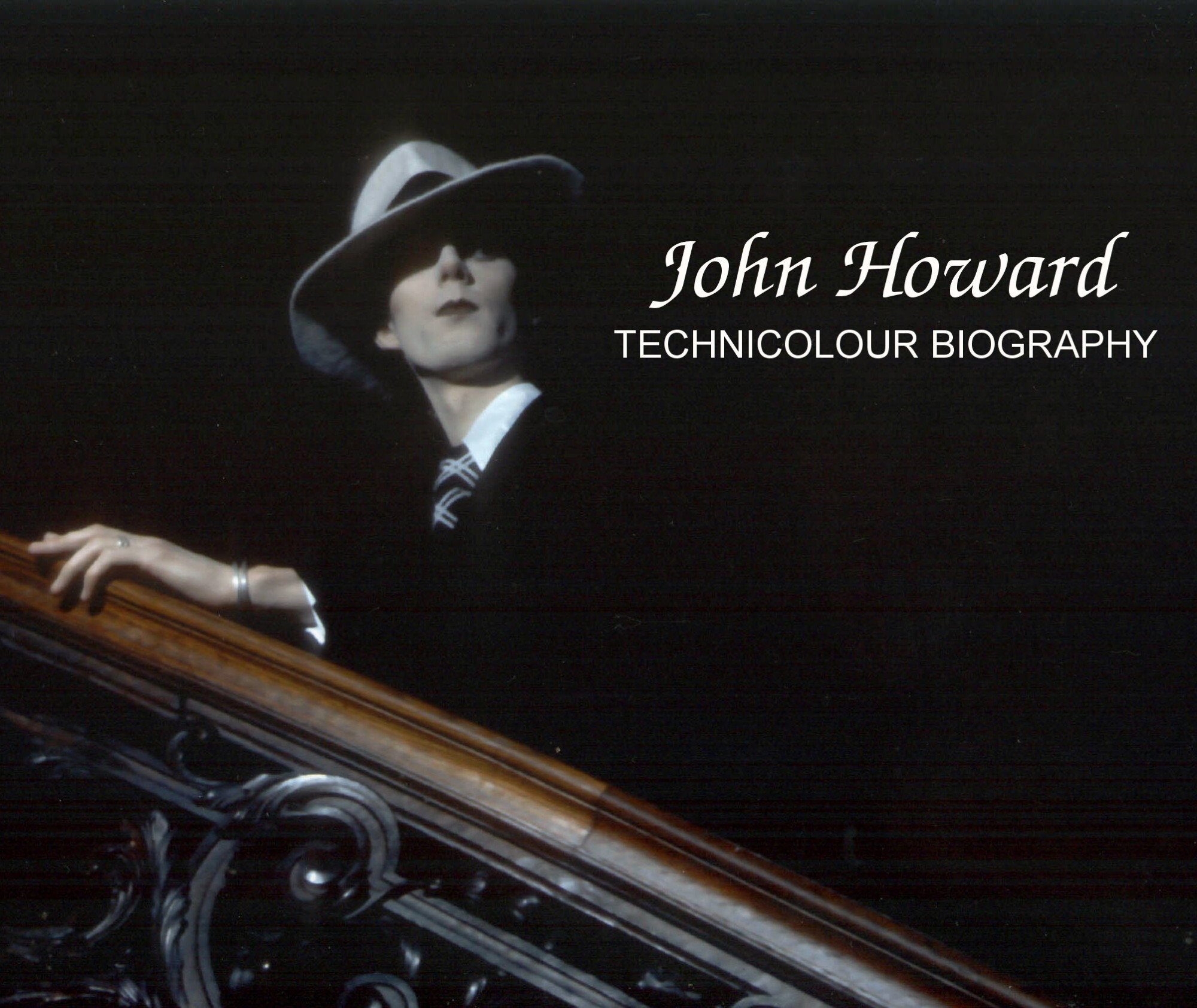

It’s hard to digest their decision to cancel your second album, ‘Technicolour Biography’. There must have been a big blow for you?

It was certainly a huge surprise and a deep disappointment. Both for me and for my producer Paul Phillips. We had big plans for it, recording most of the demos at CBS Studios in Whitfield Street. I have the original reel-to-reel tapes, which Paul gave me a few years ago, and to read his arrangement notes alongside each track is a bit heartbreaking now. It would have sounded amazing, huge, with big sweeping strings and really very grand. Paul’s ideas were radical and beautiful and we were both convinced that it would be the perfect follow-up to my debut LP.

An example of how different things were recording-wise fifty years ago, is that I was recording the demos for ‘Technicolour Biography’ months before the release of ‘Kid In A Big World’. All through the Autumn of 1974 into the Spring of ’75.

Then one morning, Stuart got a call from Dick Asher, who was then the Managing Director of CBS, inviting us to lunch at Les Ambassadeurs in Park Lane. We thought it was to chat about plans for ‘Technicolour Biography’, when we’d be starting the recording sessions, etc. CBS had already paid Stuart the advance to make the album after all. But, after the initial pleasantries, Dick proceeded to tell us that the company was not interested in ‘Technicolour Biography’. “There are no hit songs on it,” he told us.

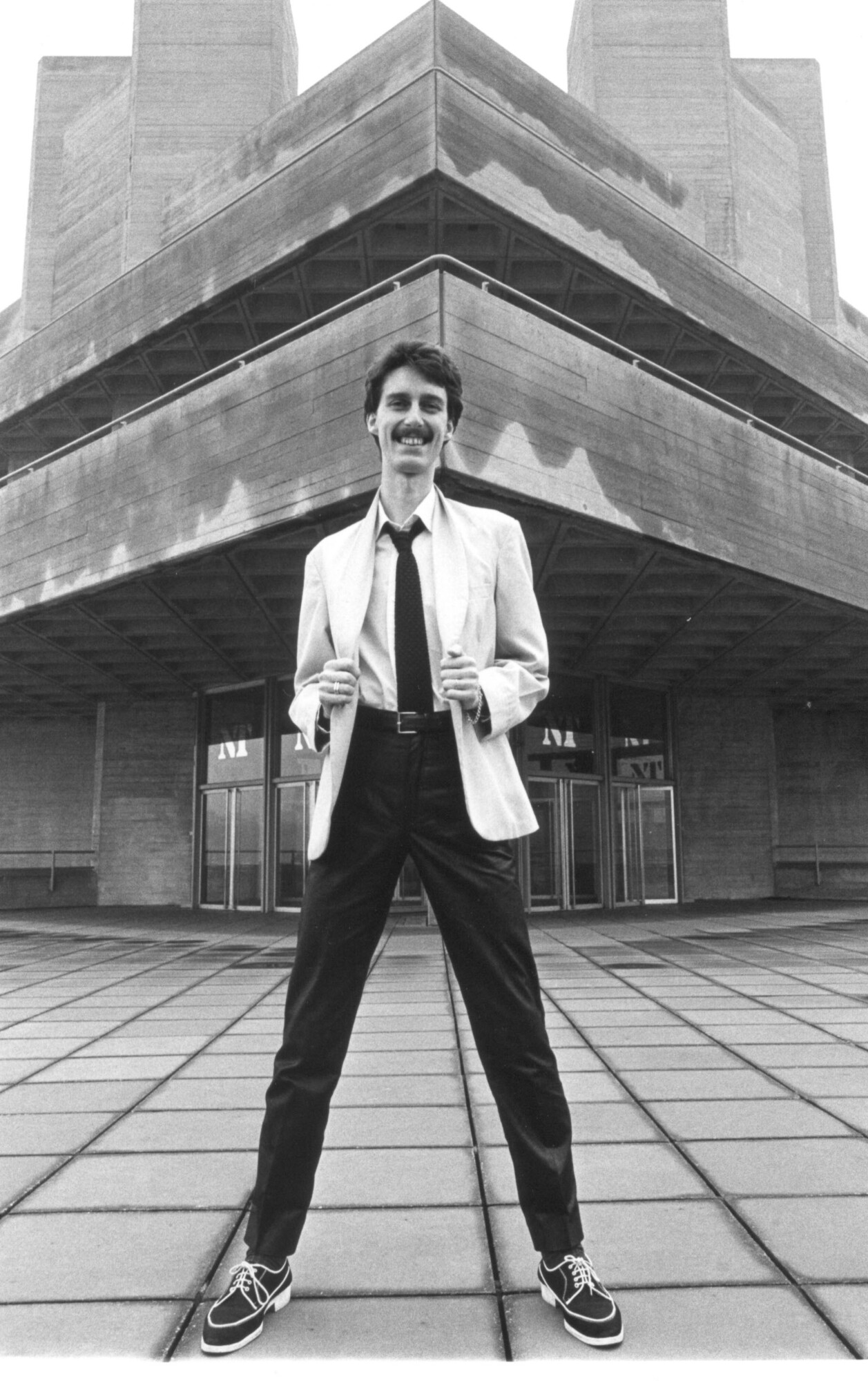

Stuart reminded Dick that just a few weeks earlier, when introducing me to the audience at The Purcell Room, where I was giving a concert to launch ‘Kid In A Big World’ in front of an invited audience of international media people, he had told everyone that, “John is not a singles artist, hit singles are not what he’s about, he’s a long term albums artist who we are going to develop and let him grow naturally.”

Dick just smiled at Stuart’s gentle rebuke, and continued to tell us that the company wanted an album of hit songs, and that Biddu would produce it. Biddu was actually a great friend of Stuart’s, I’d known him for about two years, a lovely guy, and a fan of my music. But he was a Disco man, his artists were Carl Douglas, who’d had a hit the previous year with ‘Kung Fu Fighting’ and Tina Charles, who was a young pop-soul singer Biddu was writing songs for, and about to hit No.1 with ‘I Love To Love’. I couldn’t see how our styles would gel. However, as far as Dick was concerned, it was clearly a fait-accompli. It was ‘Hit-packed album produced by Mr. Disco’ or nothing.

Thankfully the album was issued and it’s truly a wonderful follow-up. What do you remember from working on those songs?

Thank you. I was so happy when RPM put Technicolour Biography out in 2004. I wrote most of the songs during lunch breaks in the Abbey Road sessions or when Tony and Peter were setting up the mixing desk and getting to work on a track. When they were ready, Tony would call me up to join them but often I was left to my own devices for half an hour or so and that’s when I sat at the piano and worked on my new ideas.

Songs like ‘Blink In The Darkness’, ‘Lonely Woman’, ‘Hall of Mirrors’, Take Up Your Partners’, ‘Oh Dad’, ‘Just Waiting Here For You’, ‘The Other Side of Town’, were all written at Abbey Road over the course of several weeks. ‘Technicolour Biography’ was a song I’d started writing in about 1971 but I completed it at Abbey Road. Others, like ‘Don’t It Just Hurt’ and ‘Coconut Bible’ I’d written in around 1972 and always wanted them to appear on an album.

Incidentally, at Paul Phillips’ suggestion, I recorded an album in 2012 called ‘You Shall Go To The Ball!’, where I re-approached many of the ‘Technicolour Biography’ songs, giving them full arrangements and the kinds of production and backing which may have happened if Paul and I had been allowed to complete the LP back in 1975.

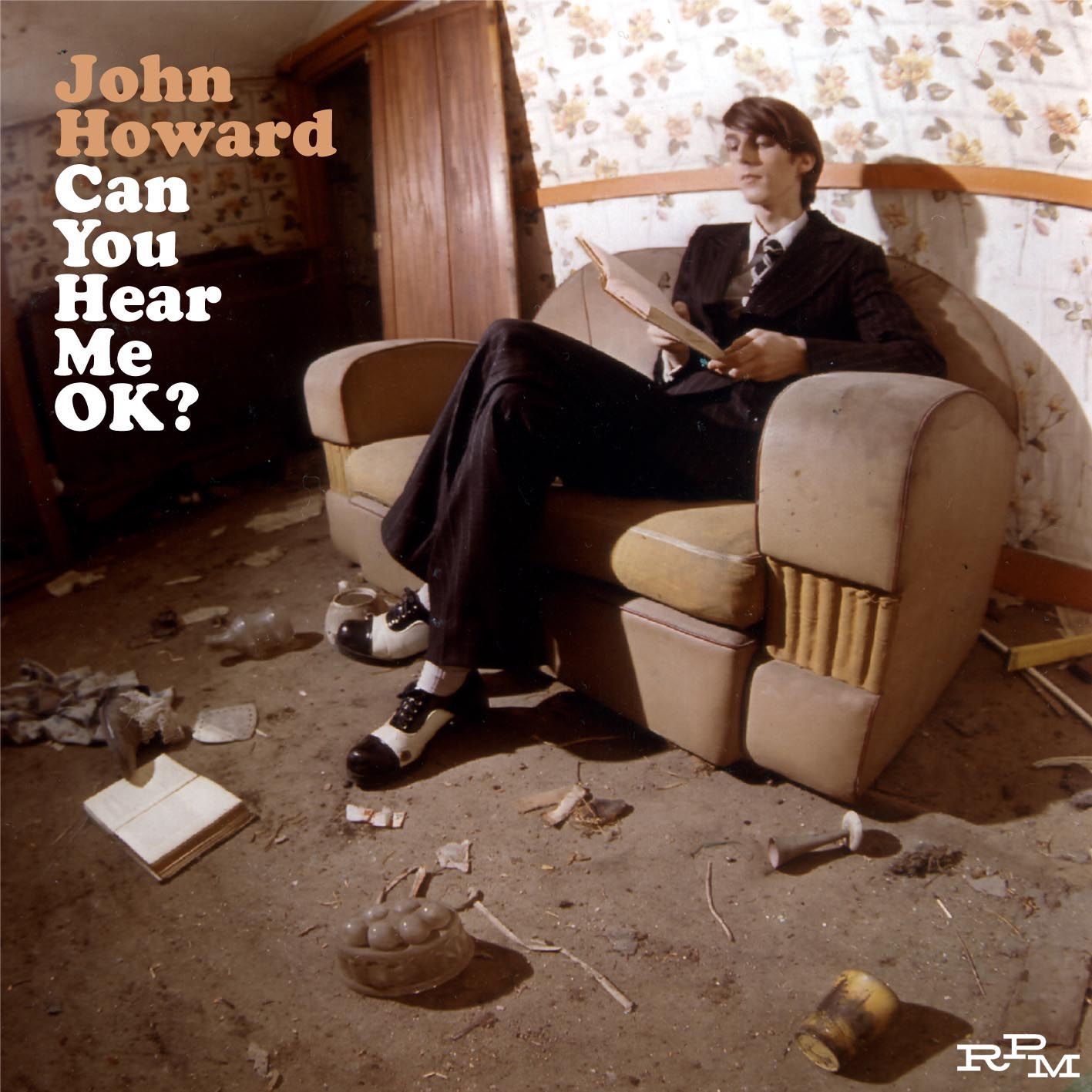

What were the circumstances surrounding ‘Can You Hear Me OK?’?

Maybe because I was a little unsure about Biddu producing me, which Dick Asher must have seen on my face at our lunch, CBS suggested that I record two new songs with Biddu in April ’75, to see how we got on together in the studio and to make sure the teaming worked. If the sessions produced tracks everyone was happy with we could proceed and make the whole album.

I went along to Biddu’s house and played him ‘Frightened Now’ and ‘I Got My Lady’, which I’d written a few days earlier. The song which knocked Biddu out was ‘I Got My Lady’. “You’ve just written your first hit song, John,” he told me. He was already swaying to a rhythm in his head as I played and humming a counter melody in the choruses. As with Tony Meehan, Biddu recorded the songs on his Dictaphone so he could send them to his arranger, Gerry Shury.

We were booked into Nova Sound Studios in Marble Arch in the third week of April, and the sessions over a couple of days were great fun. There was a sense that we were recording a hit single, Gerry Shury’s arrangements and Biddu’s chunky production all adding to the feeling that the tide was turning.

We were right, CBS loved the tracks, immediately scheduling ‘I Got My lady’ into a July release slot – “It’s a Summer smash, John!”, Dan Loggins told me over lunch at Stuart’s office in Denmark Street. We were given the green light to record eight more tracks.

I’d been hard at work trying to come up with more hooky, commercial-sounding songs, and I found Biddu’s new arranger for the project, Pip Williams (Gerry was busy working with another of Biddu’s artists) really lovely to work with.

Instead of my going into a studio to record a set of demos, Pip used to come to Stuart’s office every day where I’d play him my latest songs, he’d record them on his Dictaphone (clearly a must for producers and arrangers in the ‘70s!) until we had eight ready for the album sessions.

I loved what Pip came up with, all his arrangements were absolutely beautiful. There were full strings and fascinating extra accompaniment, like a solo violin on ‘Can You Hear Me OK?’, sitar and piccolo trumpet on ‘Two People In The Morning’, speeded-up guitar on ‘You’re Mine Tonight’, a lush, slowly enveloping orchestra on ‘You Keep Me Steady’ with a fabulous oboe opening and a truly breathtaking orchestral accompaniment on ‘19th September’, which I’d written as a tribute to my mother who had died on that day the previous year.

When Stuart delivered the tapes to CBS in August, we were waiting for an enthusiastic call from Dick or Dan, or someone at the label. But there was complete radio silence. I’d begun to get worried when July came and went with no mention of a release of ‘I Got My Lady’ as my new single. Stuart discovered that it had been simply put on hold for no reason.

Eventually, fed-up with getting no response to the album tapes, Stuart went into see one of the marketing managers at CBS (their office was literally just across the road from his office, in Soho Square, by then), and was told that the company didn’t rate the album and had no intention of putting it out.

Completely confused and wondering what was going on, Stuart invited Robin Blanchflower, one of the A&R guys at CBS, for lunch, to try and find out why the album had been shelved. After a pleasant lunch and music biz chit-chat, Stuart asked Robin outright what the problem with my album was. In response, Robin started banging his hands on his knees and singing a speeded-up ‘You Keep Me Steady’ in the style of an uptempo disco song. When he’d finished, he turned to me and said, “That’s what we expected, John! You and Biddu should have given us an album full of those sorts of things, uptempo, dance numbers with great hooks. Instead it’s a lush, orchestral MOR album!”

But two of the singles were released at the time?

No, just the one. CBS unexpectedly put out ‘I Got My Lady’ as a single in January 1976. Stuart had seen Dan in the street in mid-December and told him that I was appearing on a Christmas show on BBC TV with Johnny Mathis and Lynsey de Paul, performing ‘I Got My Lady’, and also that I would be guest artist on the Max Boyce show at the New Victoria Theatre in January. The record got a lot of play on Capital Radio but, once again, Radios 1 and 2 refused to touch it so it bombed.

What followed for you?

Well, I was dropped by CBS in February ’76, or rather they offered to keep me on the label as long as I agreed to only write potential singles, submit them for approval to the A&R Department and then record whatever they thought could be a hit – and they still might refuse to release it if they didn’t like the recording. Stuart turned that option down out of hand, declaring I would basically be a prisoner of CBS, unable to move forward creatively or sign with anyone else.

It meant I was now without a record label and lacked any impetus to write anything new. Just a year earlier I’d been feted by CBS staff at the concert I’d given at The Purcell Room to launch my debut LP, and now, here I was, floating nowhere.

My manager’s wife, Patsy, came up with an idea. She suggested I audition at one of London’s most fashionable restaurants/bars, April Ashley’s AD8 in Knightsbridge, to become their resident artist. I wasn’t too sure about it, it felt like a step backwards, but the audition went well and I actually enjoyed performing again. Over a few weeks I built up a small following of diners who would book their tables whenever I would be on, and soon word spread and other music-orientated eateries were booking me, Morton’s in Berkeley Square, Porter’s of Piccadilly and The Last Resort in Fulham. I was only doing covers, of course, but making good money and building an entirely new following. Not pop fans, but a kind of cabaret circuit group of wealthy diners who would come back week after week to see me perform. It wasn’t the career I’d planned when I moved to London in 1973 but, hey, it was a career in music. And I was earning, for the first time in my life, really good money.

That came to an end a few months later in October 1976 when I had a serious accident at my flat in Earl’s Court, breaking my back and ankles, and I had to spend many months recuperating once I got home.

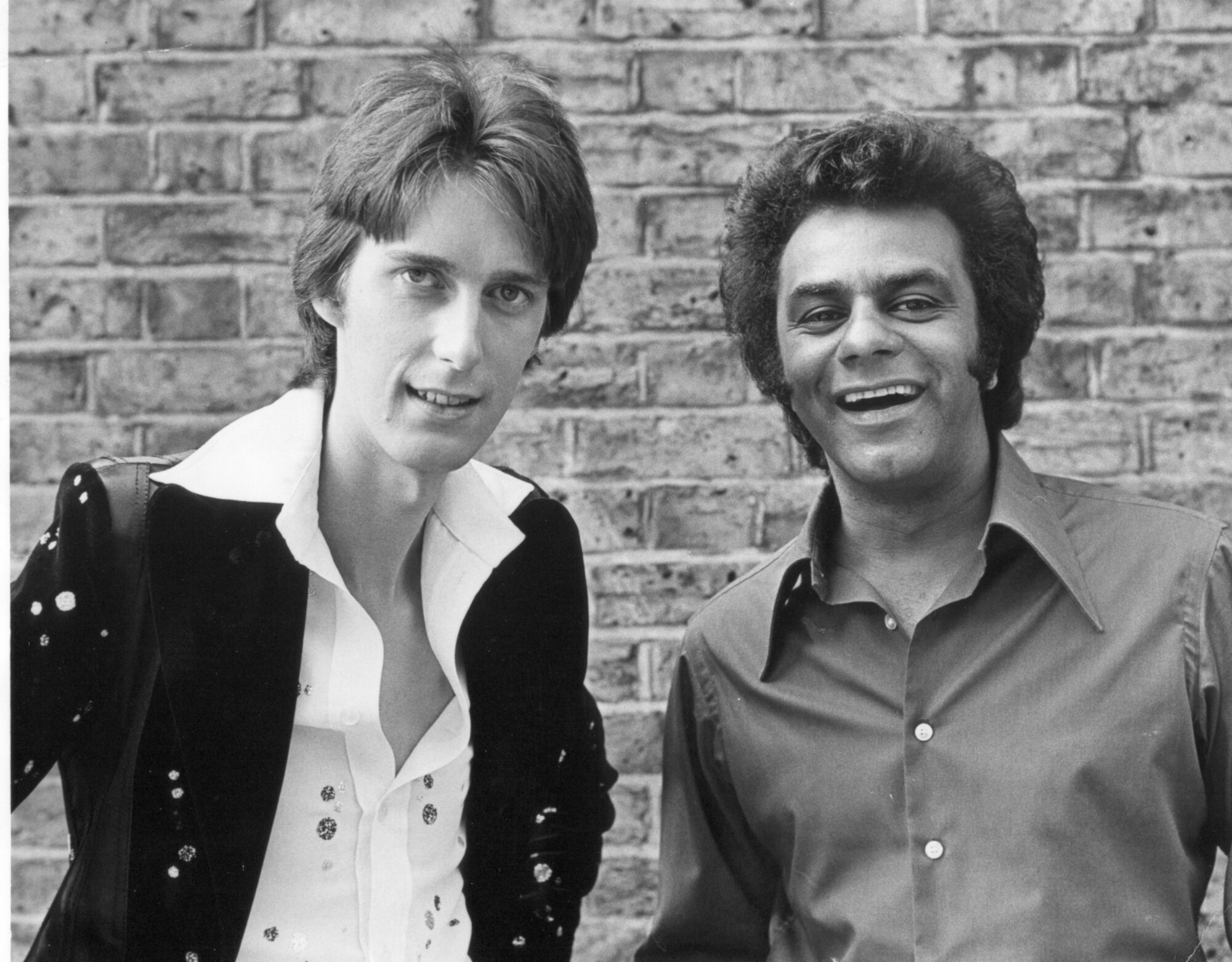

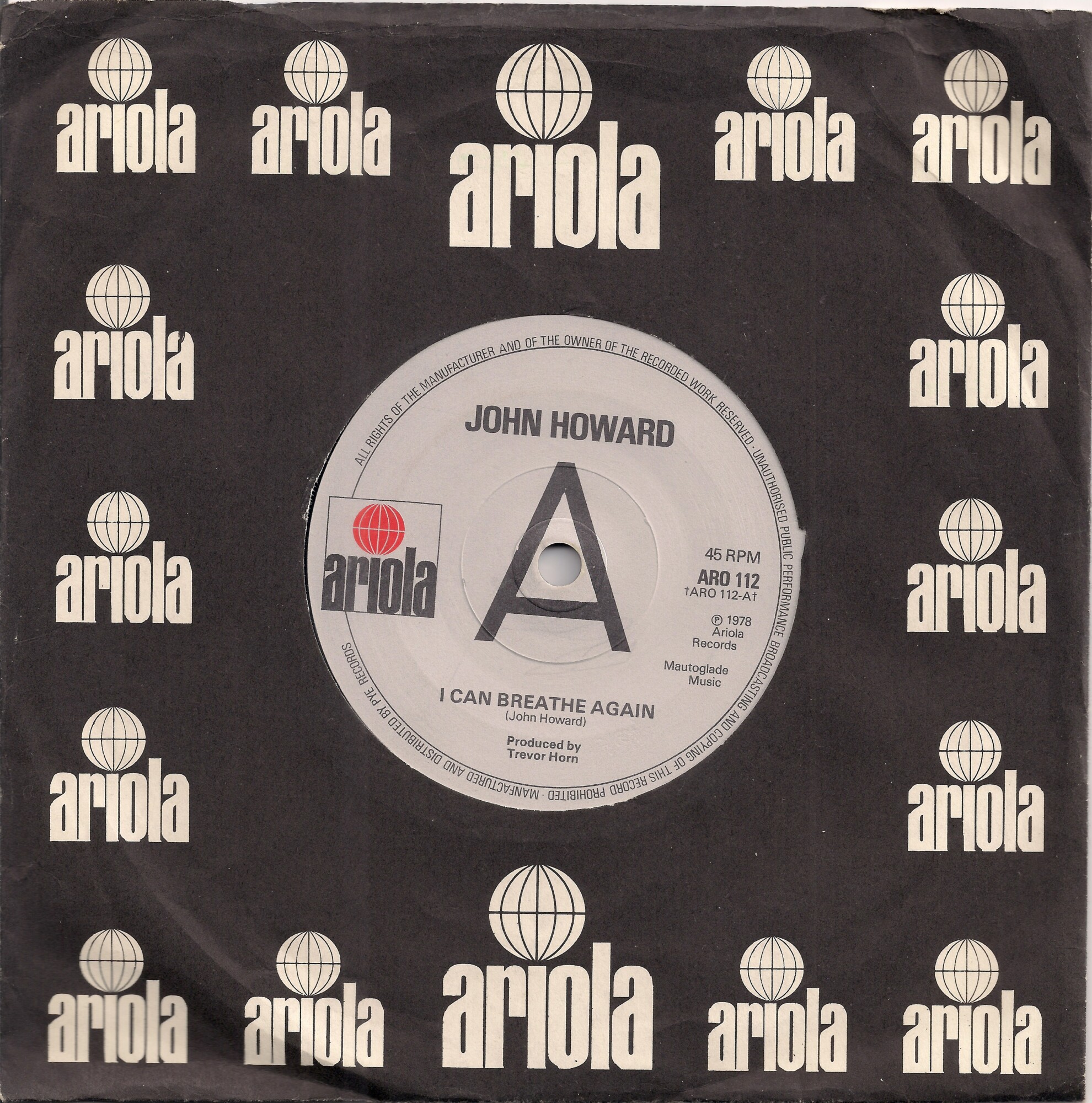

Finally, in the Spring of 1977, Stuart introduced me to Trevor Horn, then an ambitious young producer looking for a hit record. He was dating Tina Charles at the time, who Stuart was acting as tour manager for, and I’d written a song called ‘I Can Breathe Again’ with Tina in mind. When I played it to Trevor he immediately said that I should record it. It was an uptempo Bee Gees kind of song, which I sang in falsetto to try and give it a Tina Charles feel.

The recording session went well, Bruce Woolley played guitar, Geoff Downes played keyboards, Linda Jardim sang backing vocals with Kip Trevor, and I ‘Barry Gibbed’ it up something rotten! Ironically, it was Robin Blanchflower, who was now running Ariola UK, who signed the track up and released it as a single in February 1978. I finally got some Radio 1 play and things were briefly looking good but the single seemed to suddenly peter out just as interest was growing at radio.

I recorded another single with Trevor, ‘Don’t Shine Your Light’, again a Bee Gees-esque number, featuring the same band plus Anne Dudley on additional keyboards. We were expecting it to be my Autumn ’78 single, so we were very surprised when Robin turned it down. SRT Records finally came to the rescue many months later and released it in late 1979.

Radio play began growing for the single, but I had by then re-signed to CBS to make two singles with Nicky Graham (later writer and producer for Bros) and Trevor had moved onto fronting Buggles. Without promotion, the single faded, and in 1980 I released ‘I Tune Into You’, a synth-driven electronic number CBS had high hopes for, and ‘Lonely-I’, a kind of Beat-esque number in the style of their current hit, ‘Mirror In The Bathroom’. But as neither single charted, CBS once again lost interest and dropped me.

Then came Quiz?

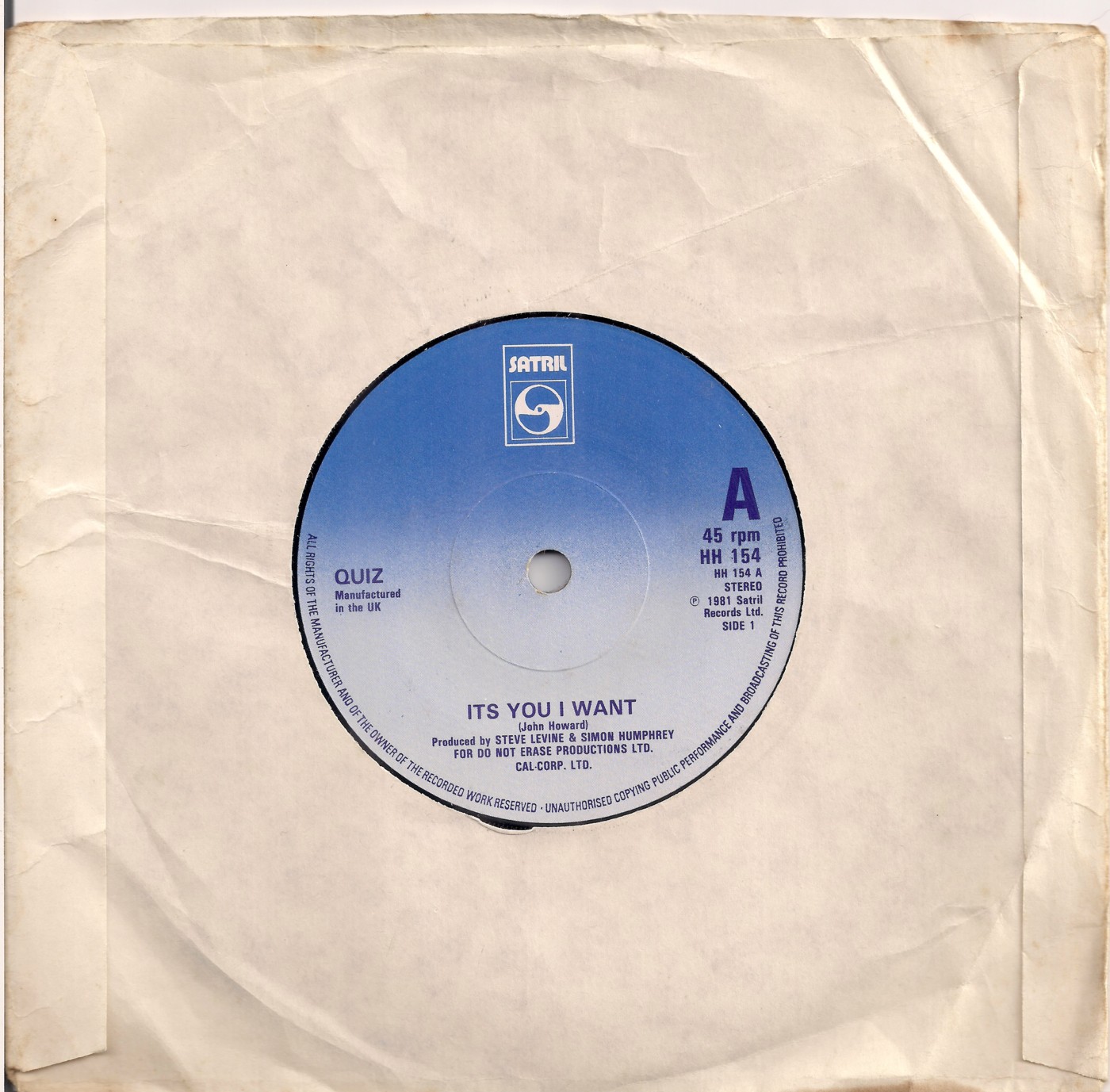

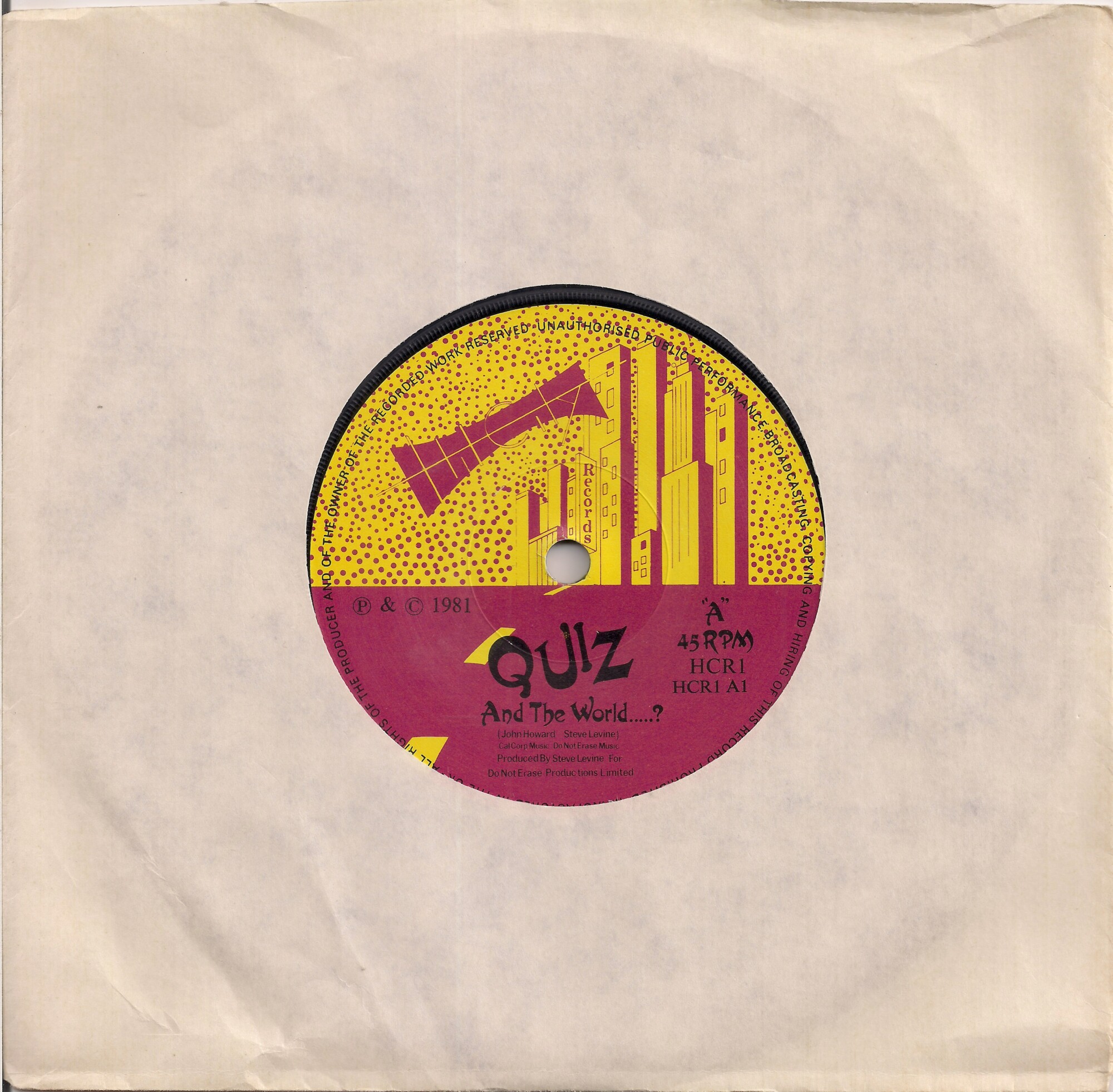

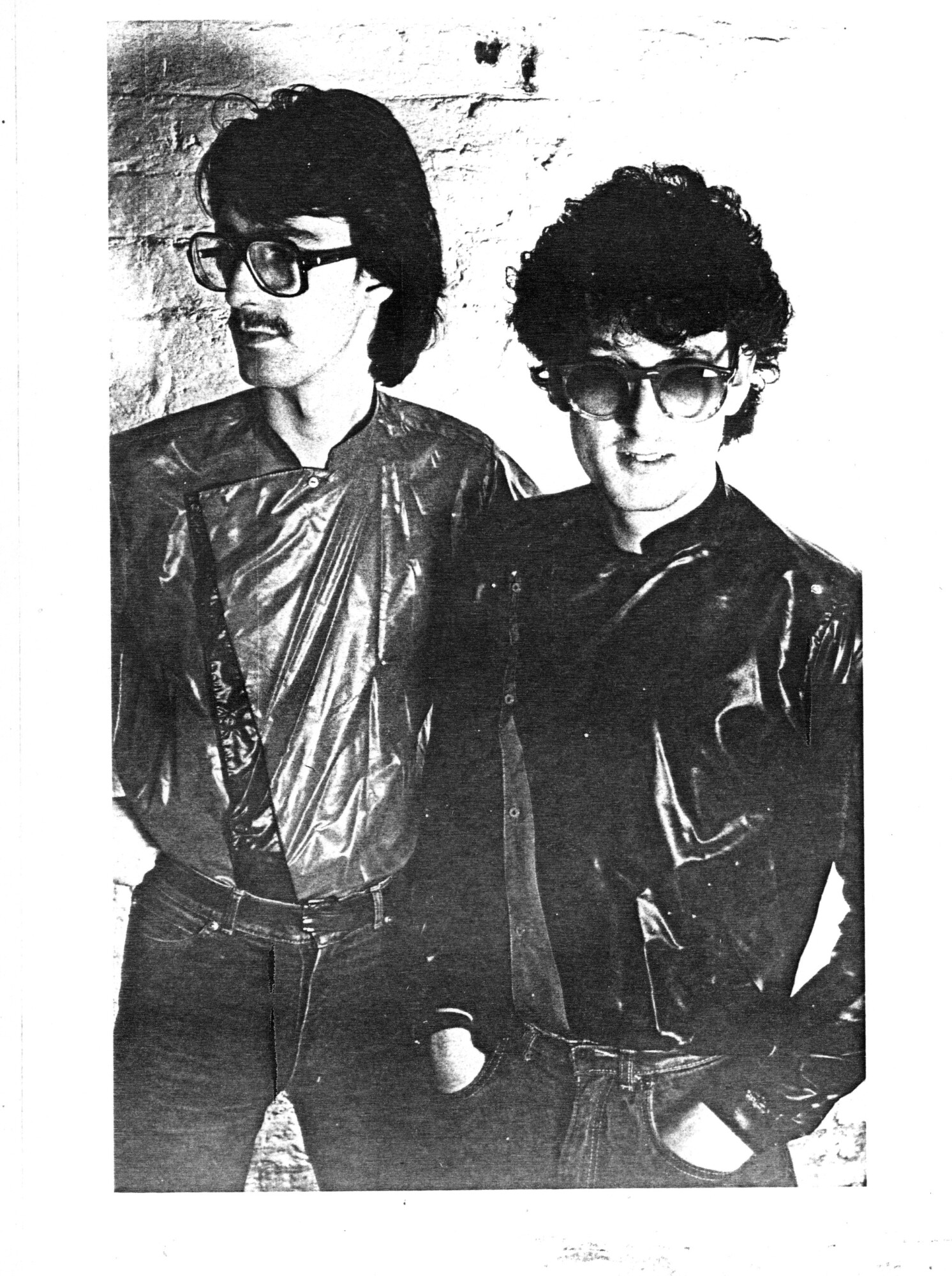

Yes, that was a Steve Levine project. We made two singles, ‘It’s You I Want’ and ‘Call On You/And The World’ in 1981. I’d met Steve during the Nicky Graham sessions at CBS. He’d been a tape op there in the mid-‘70s and had by then moved onto writing and producing. Whenever Nicky had a meeting, Steve would sit in as producer and we got on really well. So when my CBS deal ended, and Steve rang and asked me if I fancied making a record with him, I immediately said, “Yes!”.

The guitarist was John Alder, who was in The Jags and the drummer was Graham Broad who did sessions for Bucks Fizz. Satril Records issued the first single, which got a lot of Capital Radio airplay – but again nothing on Radio 1 – and Steve released the second one himself on his own label, Hit City.

Neither did very much, but a few months later Steve and I were writing and recording some demos at a studio in Parson’s Green. He’d just signed a publishing deal with Rondor Music who owned the studio, and they wanted as many songs from Steve as he could provide. While we were mixing the tracks, a chap called Jon Moss arrived to talk to Steve about his band, Culture Club. Steve had been recommended to Jon by someone at EMI to produce the band, and the rest, as they say, is history. That chance meeting changed Steve’s life in a big way.

I went onto work for various music companies, in A&R, Special Projects, Licensing, Marketing, and I basically forgot about recording for several years. My dream, so I thought, was over, and it was time to face reality and make a new career for myself.

You’ve been a songwriter for your whole life, what makes a good song in your opinion?

Oh, that’s a difficult question to answer. I certainly don’t know what makes a hit song, or I’d have written one by now! There are so many genres in pop music now, some of which I don’t like but they all have a technique which is necessary to master to engage the audience they’re hoping to appeal to.

My own personal taste is always for a great lyric which speaks to me, a beautiful chord structure, with unexpected twists and turns, and a melody which does that “click” thing when you hear it, when it creates a real shiver down the spine. For some reason certain songs immediately strike you as special, and everyone is affected differently by different songs.

Brian Wilson does amazing things with chords, McCartney does great things with melody and arrangements, Rufus Wainwright creates almost classical pieces which lift you as they soar, k.d. lang touches the heart with her sublime voice. They don’t appeal to everyone but they all move me in almost magical ways. Their songs and their records are truly great.

Do you find yourself to be a perfectionist, in control, or do your ideas lead you, taking on a life of their own?

Writing songs for me is about letting the song take you in a certain direction, almost as if they’ve already been written in the ether and just need me to make them real. It feels like teamwork with an unknown entity. I guess that’s what they call the Muse.

By the time I start the recording process, once the song is entirely finished and ready, I enjoy seeing how an arrangement develops, a certain chord structure can change where a track moves to, a certain overdub gives you more ideas of what else to add – or also take out. It’s a very organic method I use. But yes, I do consider myself a perfectionist. I would never release anything until I was 100% certain it’s the way I want it.

My vocals take a long time to record as I want them to be absolutely right. I follow Tony Meehan’s approach there – keep working at a line until it sounds right, even if it means dropping in a phrase or even a word sometimes. Now that I am under no pressure to produce something by a certain date, I can take as much time as is necessary to get the result I know is there, it just needs working at until perfection – or my idea of perfection – has been achieved.

Your music has a timeless quality to it, is that quality important to you?

I think apart from when I tried out Disco and Electronica in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, I have never really changed my style. I’m writing songs now which I could have written in 1973, there’s no difference in my approach or intention. I’m not trying to create ‘a hit’, or something pop radio is going to be all over. I just enjoy writing songs in my own style, which is true to me. That was how I wrote ‘Goodbye Suzie’ and ‘Technicolour Biography’ in the ‘70s, and it’s how I write songs like ‘Cut The Wire’ and ‘Good Day Daniel’ now. I think that’s probably why my songs sound timeless. Apart from when I briefly attempted to write ‘hits’, I’ve never tried to write something to fit a period, to fit someone else’s style. I just try to write good, solid songs that I would buy myself if I heard them.

Have you ideas that refuse to step through the door with you? And what do you do with those sketches?

It’s rare that a song refuses to come through. By the time I’ve sat down at the piano and let a song begin its process of creating itself through my hands and the lyric in front of me, the flow has begun and grows quite naturally. Occasionally something may pop into my head which I quickly know is awful or not worth working on, but once I’m in the studio at my piano with a lyric completed and ready for a tune, I can usually engage with whatever is developing and see it through to its conclusion.

I would love it if you could share some more words about your A&R career.

My career in A&R wasn’t the usual kind of thing – that is, finding and signing up new acts and getting them songs to create hit singles and albums. I was already in my thirties when the opportunity to work with artists on recordings came along. So it was more about creating concepts for already established artists and making them happen.

I’d begun working on album concepts in the mid-‘80s for music companies, whether they be multi-artist projects or something based around a single performer. It initially didn’t involve working with the artist themselves, but, I suppose because of my musical background and having been a recording artist, the job developed into creating albums from ideas directly with the artist.

In 1989, I was given the opportunity by Virgin Records to work with Madness on a project they were keen to get released, which was all their singles, the ‘A’ and ‘B’ sides, on one album. The problem was, they had so many hits we needed two albums to fit them all on!

We called the albums ‘It’s Madness’ and ‘It’s Madness 2’, and I initially got together with the boys at their studio in Caledonian Road. They were a great bunch of guys, really friendly and enthusiastic about the project, happy to chat about and throw ideas into the concept and the sleeve designs.

Then Lee and Chris came to my office a couple of times and we decided on which singles to feature on which volume, and how they would be compiled. Lee particularly had very definite ideas about that, he wanted the albums to flow naturally rather than just put the tracks together in chronological order.

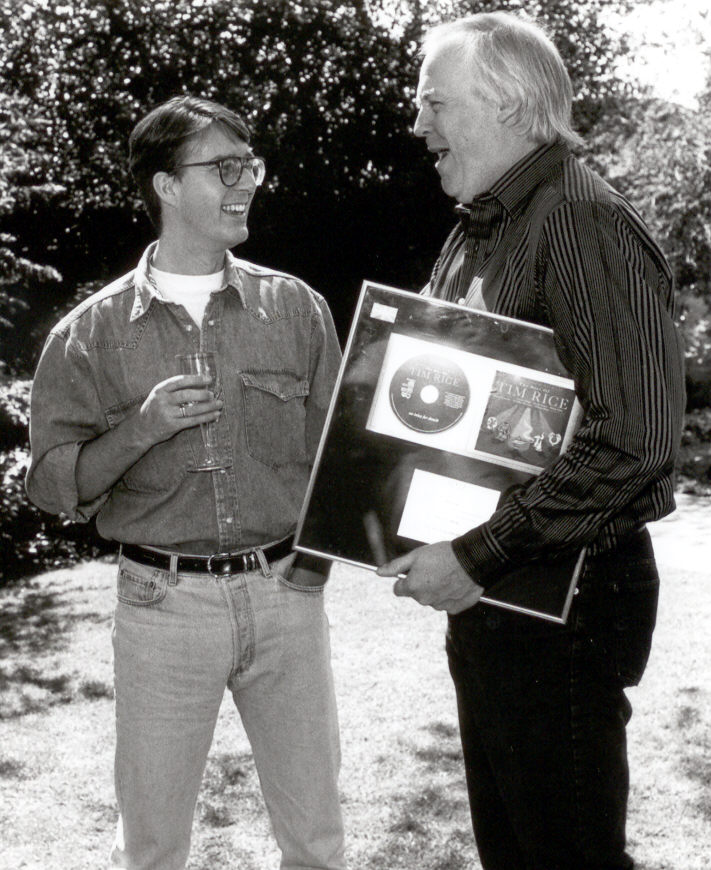

Both albums did very well, and Virgin asked me to follow them up with two Culture Club concepts. I came up with a Best Of and a more left-of-centre collection featuring the 12” remixes called Culture Club Collect. I got together with my old friend and the band’s former producer, Steve Levine, and we decided which tracks to use, which mixes and versions, and Steve even provided me with pristine masters from his personal tape library. Again both albums did well, and over the next couple of years I came up with a few more album concepts for Virgin and other labels.

One of them, for Arista, was a Barry Manilow collection. They didn’t want a Hits type thing, more a deeper delve into Barry’s album tracks and ‘B’ sides. Called Reflections, I discussed ideas for songs with Barry via fax and with his manager Gary Kief over lunch a couple of times. The album sold almost 200,000 copies, and led to me being invited to one of Barry’s London concerts and meeting him after the show. He was a real gentleman, thanking me for coming up with an album which had sold so well and which had showcased many of his lesser-known recordings.

As they say, one thing led to another, and I began coming up with concepts for new recordings with established artists. I had an idea for Elkie Brooks to do an album of Abba songs backed by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. I’d already worked with the orchestra on two successful albums they recorded for me with Tony Brittan doing the arrangements, instrumental interpretations of the music from Les Miserables and then Miss Saigon. Both were huge sellers.

I could hear Elkie in my head singing things like ‘The Day Before You Came’, ‘The Way Old Friends Do’ and ‘The Winner Takes It All’, which would also put a slightly different slant on what she’d done in the past, appealing to a new kind of audience. However, when I met up with Elkie over lunch the first thing she told me was she didn’t like Abba and had no intention of recording any of their songs! But she did love my idea of her recording with the RPO. So, we booked Elkie into AIR Studios, I asked Tony Brittan to write new arrangements for Elkie’s biggest hits, which was what she wanted to record, and over the next couple of weeks the album took shape. When it was finished and mixed, it was sensational. Her recordings of ‘Nights In White Satin’ and ‘Lilac Wine’ with the RPO still send shivers down my back when I hear them. Called Amazing, it gave Elkie a Top 50 album in 1996.

A less widely known – but equally as great an artist – who I was keen to work with was Maria Friedman. I’d seen her performing at the Laurence Olivier Awards when she’d won the Best Show award for her one-woman production, By Special Requestand, the next morning, called her manager, Alan Fielding, for a meeting. I was very surprised when he told me that I was the only A&R guy who had been in touch with him about Maria. I was certain that all the big labels would be after her.

Alan arranged for me to meet Maria at rehearsals for her next show, By Extra Special Request, which was due to open at the Whitehall Theatre, and although she was a little wary of record company people, we got on well. I think having been a recording artist myself – with several stories of the ups and downs of my career – she warmed to me and we agreed that an album featuring the songs from her show would be a great idea.

I asked Nigel Wright, who had produced many of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s show recordings, to produce Maria’s album and the two of them came up with a stunning record. Simply called Maria Friedman, it’s one of the albums I’m most proud of being involved with during those years working in the music business.

The one project I always regretted not happening was a record I wanted to make with Dusty Springfield. I’d seen an ad on TV where she sang a short snippet of the song ‘Someone To Watch Over Me’, and thought it was beautiful. I knew the guy who used to be Dusty’s P.A., Mike Gill, and suggested quite an unusual concept to him – a 3CD collection, incorporating Dusty’s biggest hits on CD1, her favourite recordings from her many albums on CD2 and a completely new set of recordings on CD3, featuring Dusty singing some of the all-time great standards.

Mike loved the idea, put it to Dusty, and called me within a few days to say she really wanted to do it. The one proviso Dusty made was that she would record CD3 in her own home studio with musicians she chose, and would produce the album herself. Mike told me that was how she’d recorded ‘Someone To Watch Over Me’ so I was totally sold on the idea.

Over the next few weeks, Mike and I chatted about the songs, which had to be Dusty’s own personal choice, and we were set to go. Then, I got a call from Mike I hadn’t expected. Dusty’s cancer had returned and she wasn’t well enough to start work on the album yet. As it turned out, her condition deteriorated, and Mike eventually rang to tell me she wasn’t well enough to proceed with the album. Dusty tragically passed away a few months later in 1999.

I’m sure she’d’ve recorded a wonderful album for me, but how it would have sounded can only exist in my imagination. Dusty had sent me a signed photo during our plans for the album, and I now have it in my own home studio, a kind of inspiration whenever I see it and yet a sad reminder of what could have been.

Your 2005 was a tremendous comeback. What was it like to work on ‘The Dangerous Hours’?

Thanks. ‘The Dangerous Hours’ came about purely by happenstance really, a kind of serendipity was in operation. RPM had just re-released ‘Kid In A Big World’ on CD, which had received rave reviews (unlike when it had first been issued in 1975). Around the time that Paul Lester in Uncut Magazine had given it a five-star write-up, in February 2004, I got a call from Mark Stratford at RPM. He told me a poet from Manchester, Rob Cochrane, had been in touch with him, saying how pleased he was that ‘Kid’ had been reissued, and he’d given Mark his address if I wanted to contact him at any time.

So I wrote to Rob and received a reply quite soon, an extremely erudite letter. Over the next couple of weeks we began a long and enjoyable correspondence about music, poetry and the kinds of artists we liked. He offered to send me some of his published poetry books and enclosed in the package was a lyric he’d written to one of his heroes, Jobriath. It was called ‘Stardust Falling’, and I instantly connected with it. I wrote a song around the lyrics and took it into the sessions I was in the middle of for an album I was working on, ‘Same Bed, Different Dreams’, and recorded it.

When I sent the recording to Rob he loved what I’d done and we got to talking about maybe doing a whole album together. Within a couple of weeks, I received three exercise books of lyrics Rob had written, picked those I liked the most and began writing songs around them.

Rob had also sent me a box of poetry cards, called ‘The Luxury of Rain’, with each card having just one line of his poetry on it, which became the basis for one of the songs, and I’d also fallen in love with a poem in one of his books called ‘The Thin Man’, based roughly on the Carry On star, Charles Hawtrey and his co-stars Kenneth Williams, Sid James and Barbara Windsor. That became the song, ‘What A Carry On’.

After a few weeks I had fourteen new songs written, based on Rob’s lyrics and poems. I sent him the home demos I’d recorded and when he gave me the green light on them, I went into a recording studio quite near my home in Pembrokeshire and spent five days there recording what became ‘The Dangerous Hours’ album.

Rob released it in July 2005 on his own label, Bad Pressings, and to our delight and amazement it got rave reviews in The Guardian and in Uncut Magazine. It was my first album release for thirty years, and suddenly I was back!

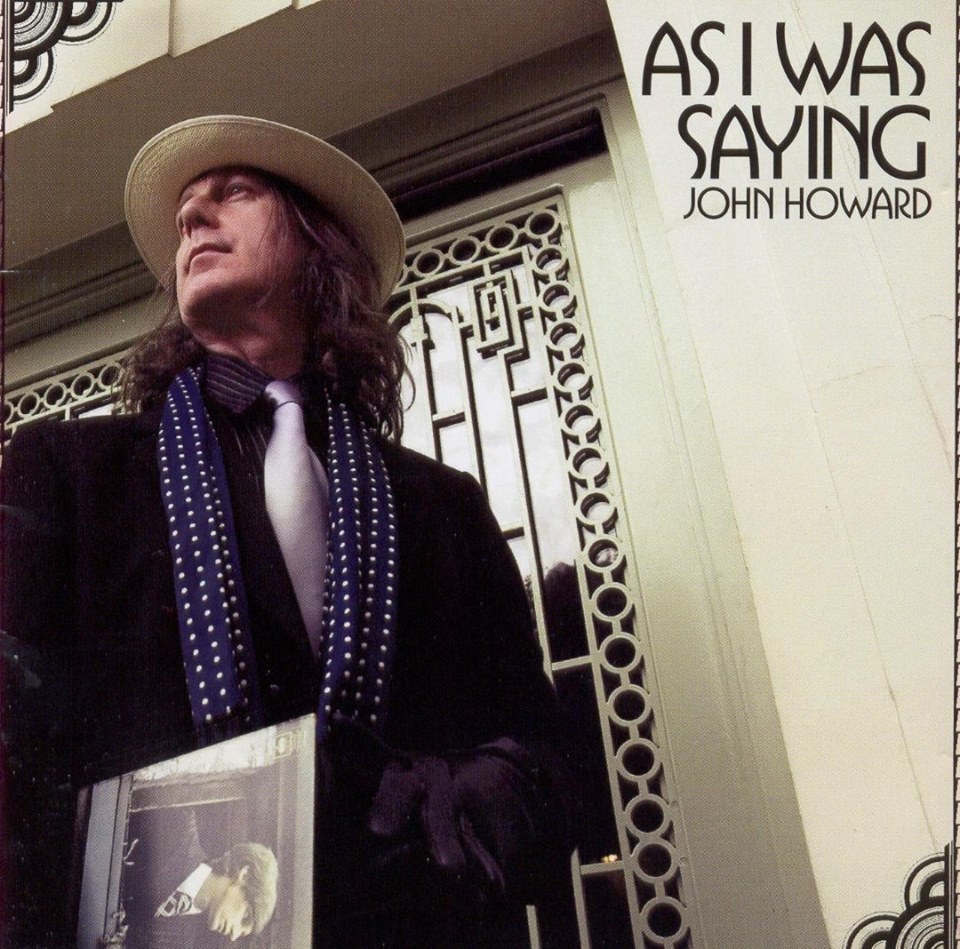

And it continued with the releases such as ‘As I Was Saying’, ‘Same Bed, Different Dreams’, ‘Barefoot With Angels’. Tell us about it.

Yes, well, once that creative tap had been turned back on, and with my confidence back on a high after the wonderful response to the reissue of ‘Kid’ and the release of ‘The Dangerous Hours’, songs literally poured out of me. Mark Stratford persuaded Cherry Red, which owned RPM, to release a new album of mine on their label, which became ‘As I Was Saying’, recorded with two fabulous musicians, Andre Barreau (most famous for being the guitarist on Robbie Williams’ ‘Angels’ and ‘George’ in The Bootleg Beatles) and Phil King, formerly with Earl Brutus and Lush. That was actually my first released album for thirty years featuring songs containing my own lyrics, and led to some great write-ups and an invitation to take part in the BBC Radio Four discussion programme, Midweek.

I then completed ‘Same Bed, Different Dreams’, which had been on hold while I finished TDH and AIWS, getting a release on the French label Disques-Eurovisions, and moved quickly onto ‘Barefoot With Angels’, which was the first album I recorded in my new home studio. Spanish label Hanky Panky heard the recordings and offered to release it.

I hadn’t ever expected to be on such a creative roll again, especially after the stop-start nature of my recording career in the 1970s. Suddenly, I was free to write and record whatever I wanted and get a release on the resultant album. It felt very liberating.

It’s wonderful that you managed to save and release many of the archive records.

Yes, it was great that Stuart Reid had got all the masters back of my first three albums in the ‘70s. He’d cleverly signed a licensing agreement with CBS, rather than a direct artist contract, with an expiration date in there, although CBS actually offered to give the masters back to Stuart before that period had expired. And I recorded a lot of demos back then too, so they have also had reissues on vinyl and on CD over the last few years.

The latest reissue is an exciting one for me. It’s a 2CD set, released by Kool Kat Musik, ‘Kid In A Big World’ + ‘The Original Demos’, featuring on Disc 1 the 1975 album and on Disc 2 the previously unreleased 1973/’74 demos I recorded of the ‘Kid’ songs. The tapes were cleaned up and restored by a brilliant guy, Javier Roldon, who lives here in Spain. The response even before it’s released has been fantastic, with a fabulous review in Shindig! Magazine, so once again, ‘Kid’ is working its magic!

Tell us about ‘Navigate Home’ and ‘Exhibiting Tendencies’?

Oh yes, they were self-release albums in 2009 and 2011 respectively. ‘Navigate Home’ was written just before my husband and I moved to Spain from the UK, then completed in my home studio in Murcia. Many of the songs reflect the feelings I had of excitement at discovering a new country to live and yet a sadness at leaving Britain. The title song still makes me quite emotional when I listen to it now.

‘Exhibiting Tendencies’ was basically about the process of aging. I was fifty-eight when I recorded it, and it investigates all the issues with getting older and more frail. I’m now seventy and I think I got it just about right! There are two tracks on it, ‘Forgetful’ and ‘Not Forgotten’ which are amongst my favourite recordings of mine. Both were quite a challenge to record – being basically a one-man band in my studio, playing everything in real time and mostly on real instruments (I can’t hire a whole orchestra obviously!). I learnt a lot recording those tracks. Every time I record an album I learn something new, some new technique so I can get down what I hear in my head.

How did the record with The Night Mail come about?

Well, that was my first album with an actual band, one who I recorded and toured with. It again wasn’t planned but kind of happened after a few conversations. I’d been introduced to Robert Rotifer, a true polymath – an Austrian guitarist, singer-songwriter, journalist, artist, festival organiser and radio DJ – in 2012 via the reviewer Joe Lepper and the singer-songwriter Ralegh Long, who was a fan of ‘As I Was Saying’.

Robert interviewed me for his ‘Heartbeat’ radio show and while we were chatting he asked me if I’d ever considered gigging again. I hadn’t performed live for a few years. He told me he and Ralegh were thinking about doing a concert at the Servant Jazz Quarters in London, which had a piano. It seemed like a fun idea so I tentatively said “Maybe.” Then he suggested I could do some of the songs with a band – featuring him on guitar, Ian Button (of Papernut Cambridge and formerly with Thrashing Doves) on drums and bassist Andy Lewis, who was then with Paul Weller’s band.

So I put a 45-minute set together and decided which ones I thought would suit a band best, sent those songs to Robert, Ian and Andy, along with my then new album, ‘Storeys’, which had just come out on my own label. The gig was booked for late November, and I travelled to London with my husband, Neil, met up with the guys, and we had one rehearsal the night before the gig which went brilliantly. These guys were great!

After we’d routined most of the songs, Robert very shyly asked me if I would consider doing the opening song of ‘Storeys’ with them, ‘Believe Me, Richard’, which it seemed they all loved. We routined it a couple of times, it sounded fab, and it was added to the set.

The gig went beautifully, the audience were wonderful, and performing with a band was a real treat, they rocked the place!

Robert called me a few days after I got back home and asked what I thought about writing some new songs with him, Ian and Andy for an album we could make together. Very soon, we were sending each other lyrics and working on songs around those lyrics, all of which I demo’d in my studio in preparation for the recording sessions, which had been booked at Big Jelly Studios in Ramsgate for November.

“As you’ll be coming over to the UK for the recording sessions, why don’t we do another gig at the Servant Jazz Quarters the night before we start on the album?” Robert asked me.

So we did. The gig went great and the following morning we all set off for Ramsgate. Big Jelly was a lovely studio, modelled on Abbey Road, which for me was quite a nostalgia trip! Over four days, we recorded eleven songs, ten of our own and a cover of Roddy Frame’s beautiful ‘Small World’, which Robert had suggested.

He also came up with the band name, insisting it should be ‘John Howard and…’, although I was thinking more of an actual all-in name rather than highlighting mine.

The boys then mixed and mastered the tracks, sending me the various stages of mixing for my thoughts and comments, and once it was finished, Robert sent it to a German record label, Tapete, based in Hamburg, who he knew of. They’re quite a major indie there. They absolutely loved the album, scheduled it for an August 2015 release, previewing it with the single ‘Intact & Smiling’, which I’d written with Andy. It actually got into the Austrian Indie Top Ten, as did the album! My first chart hit!

The album went onto become Metacritic’s fifteenth best-reviewed album of 2015. I think it got something like twenty-five five-star reviews.

Next year, I’m planning to release the piano & voice recordings I made of ‘The Night Mail’ songs, and the preparation demos I sent to the guys before the sessions. It’ll be called Single Return, a nod to the train theme. I checked with Ian, Andy, Robert and Tapete how they’d feel about the release, and they all gave me their blessing – Robert actually saying, “I always thought you should put those tracks out, John!”.

Would you believe that I first heard your music via ‘Across the Door Sill’?

Well, that’s a good start! I have always been very proud of that album. It was released by Occultation Recordings, and was very much an experiment, coming straight after ‘The Night Mail’ release. I wanted to try to make an album featuring just my piano and voice, but incorporating lots of pianos and lots of my voices! I wrote all the lyrics as long-form poems and then set them directly to music, without rewriting or restructuring the words, just letting the poems create the songs’ structures. It’s quite a dreamy album in many ways, featuring stream-of-consciousness lyrics. Four of the five tracks are around nine or ten minutes long. What surprised me was how well it was received, getting some of my best solo reviews of my career.

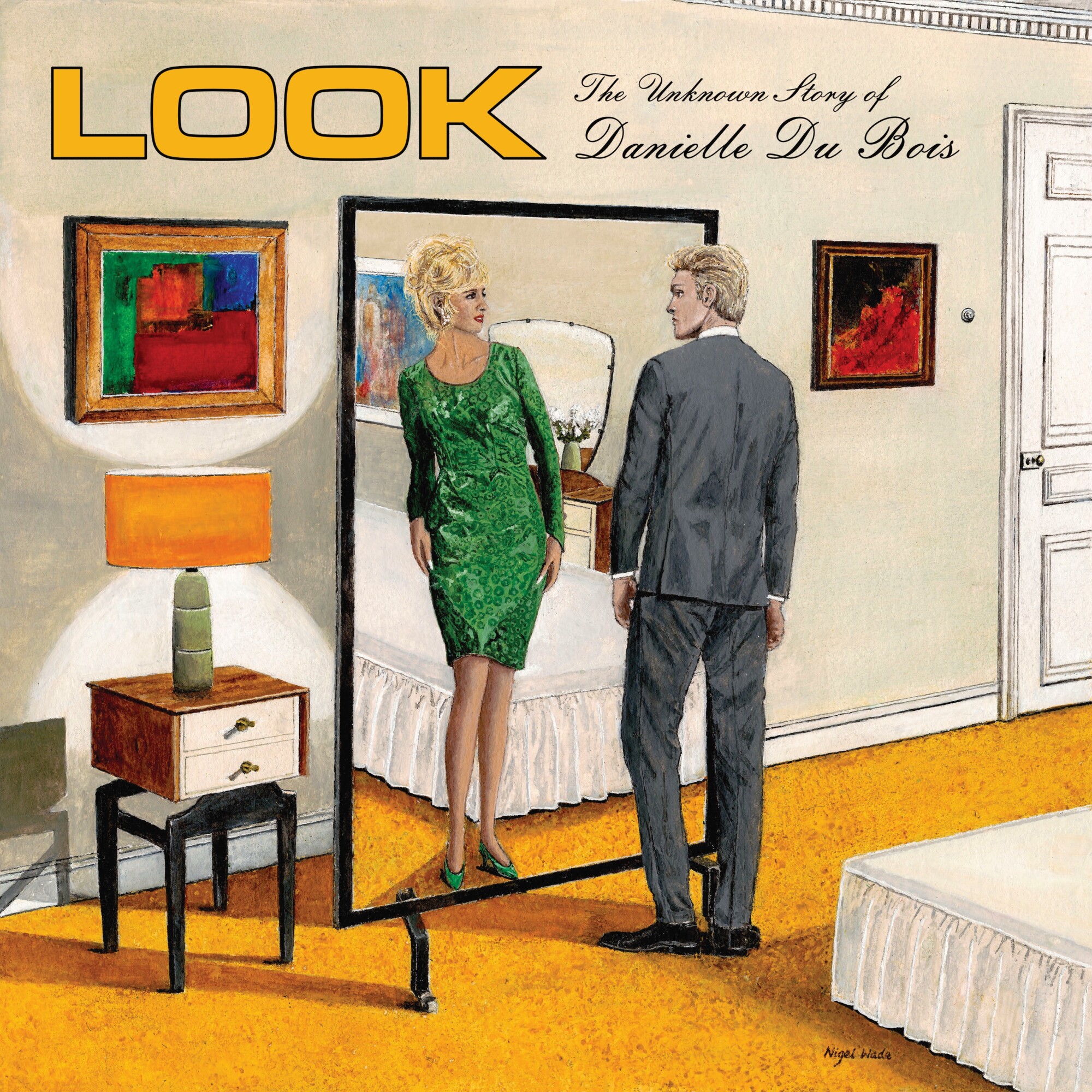

Your latest album, ‘LOOK : The Unknown Story of Danielle Du Bois’ seems to have a very interesting concept behind it. Tell us more.

Well, since Kool Kat Musik released ‘LOOK’ in the Spring of 2022, they’ve also brought out ‘From The Far Side of A Near Miss’ in September last year, which features just one thirty-seven minute song. But, talking about ‘LOOK’, the album’s story was loosely based on April Ashley, who transitioned from male to female in the early ‘60s. She had an incredible life, full of many ups and downs and was a marvellous, extremely brave, resilient person.

I first met her in 1976 when I played at her Knightsbridge restaurant/club AD8. It was a really stylish place with a white grand piano at one end, and used to get many stars coming along for the food, the music and “to be seen”.

April and I lost touch for a while but after a friend of mine sent her my song, ‘Magdalena Merrywidow’, which was dedicated to April and is on my album ‘Barefoot With Angels’, she and I began emailing and occasionally phoning each other.

‘LOOK’ was a kind of extension of ‘Magdalena Merrywidow’, but instead of a story-in-song, it was a story-in-an album, something I’d never done before. I constructed the album, the narrative, chronologically, starting with the fictional character, Daniel Wood’s life as a child in the 1940s, teenager and eventually an entrepreneurial pop star by 1961.He had always known that he was ‘in the wrong body’ and longed to become a woman. Once he had the funds to do it, via his huge success in music and film, Daniel flew to Paris and transitioned into Danielle Du Bois, a wealthy socialite mixing with the likes of Pierre Cardin, Brigitte Bardot and Josephine Baker.

There was talk of ‘LOOK’ being turned into a stage musical, but so far that hasn’t happened, but who knows, maybe one day! I’d planned to send April a copy of the album but she died while I was recording it, so sadly she never heard it, but I hope she’d’ve liked it.

Can you share some further words about the latest album and its recording and producing process.

Because I wanted the album to have quite a lot of drama and a running narrative, seeing it as a possible stage production as much as a long-player, I had to assume different roles for the tracks. Sometimes I was ‘Daniel’, other times ’Danielle’, other songs like ‘The Mirror (Look!)’, feature Danielle’s ‘Guardian Angels’ who care for Danielle throughout her life, even when she’s dying they help her soul travel into the ether.

One of the songs, ‘I May Be Old But I’m Still Gorgeous’, features not just an aging Danielle in cabaret but her whole troupe of fellow performers at a club in Paris. It meant using audience sound effects, which Ian Button, who mastered the album, accessed for me, and they give it a terrific live quality. Multi-tracking myself as different characters on stage with Danielle was great fun. It still makes me laugh when I listen to it.

There’s a fantasy number at the end called ’16 (Woo! Woo!), where we see an imaginary young Danielle – the Danielle who Daniel had dreamed of being –doing a song with her classmates, who are all celebrating being teenagers and doing their own thing with abandon. Again, the recording process and my many multi-tracked performances had to attain that sense you were listening to several people singing and dancing on stage.

The album opens and closes with a child singing the nursery rhyme, ‘Johnny’s So Long At The Fair’. I used a 1958 recording of me, aged five, singing the song to my father’s piano accompaniment, and added more keyboards and built the effects to create a kind of dream-into-nightmare scenario, which Daniel had suffered as a child.

It was a complicated album to conceive and record but it’s one I will always be proud of. Again, such projects take me a long time as I’m doing everything myself, but it’s always rewarding when it works out and is then received so positively by my fans and the media. One reviewer made it his Album of The Year.