Axolotl | Jacques Oger | Interview

Jacques Oger is a French saxophonist that was involved with a very interesting project called Axolotl. He also founded the French independent label Potlatch in 1997.

In 1981, encouraged by Jac Berrocal, Axolotl consisting of Etienne Brunet on alto saxophone, bass clarinet and Jacques Oger on tenor and baritone saxophones, Marc Dufourd on electric guitar, recorded an album of French-style free music as iconoclastic as it was unsettling: free improvisation, jazz, no wave, contemporary, punk… a dance of labels which leaves plenty of place for the direct expression of a monstrous trio of regenerated agitators! The axolotl is a species of salamander native to Mexico, living in a state of larva and having the capacity to regenerate damaged organs.

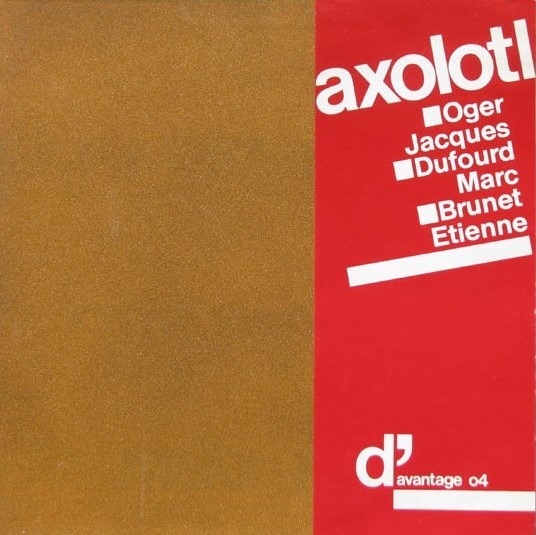

In Paris, at the end of the 1970s, Etienne Brunet and Marc Dufourd would improvise regularly, inspired by some other saxophone-guitar duos: Claude Bernard-Raymond Boni firstly, then Evan Parker-Derek Bailey. When Jacques Oger (a saxophonist whom Brunet had met at a workshop given by Steve Lacy at the Châteauvallon festival in 1977) joined the duo Brunet-Dufourd, Axolotl was born. Iconoclastic, the trio was bound to please Jac Berrocal, and he proposed to record their first album on the label D’avantage. In spring 1981 three days were just enough for Oger (tenor and baritone saxophones), Brunet (alto saxophone, bass clarinet and other) and Dufourd (electric guitar) to complete Axolotl, the first album by a group which would record … two.

SouffleContinu Records recently reissued ‘Abarasive’ on vinyl.

“We wanted to make something different from strictly acoustic improvisation”

How did you first get interested in music? Were any of your parents musicians?

Jacques Oger: There was not so much music at home when I was a kid. No record player, only the radio. So I could listen to mainly French singers: Edith Piaf, Barbara (Monique Andrée Serf), Charles Aznavour, Jacques Brel (who is Belgian anyway…), and many others. Later on, in the mid 60s, there were a lot of radio broadcasts with a breaking wave of new American and British pop musicians, among these: Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, The Animals, The Kinks, The Beatles, The Beach Boys, Donovan, Jimi Hendrix Experience, Otis Redding, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Fats Domino, Janis Joplin, Sam & Dave, The Yardbirds, Cream, The Who, The Doors… At the same time, I could listen to a lot of jazz on the radio too. I read some jazz books: Really the Blues by Mezz Mezzrow; and a history of jazz (“Jazz”) written by French journalist André Francis. I started reading Jazz Magazine. So I knew many names and photos of jazz players even if I had never listened to them! My parents bought me a record player and I started buying some jazz records. I was living in a small village in western France, but anyway it was very easy to find all this stuff in a record shop in the next town. So I started listening to Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, Sydney Bechet, Fats Waller, Ray Charles, Archie Shepp, Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler…

Was there any particular moment when you knew you wanted to become a musician?

I never wanted to be a musician. However, I was given some piano lessons at the high school when I was a teen. And I was trying to play blues songs. Clumsily anyway. Later on, with two friends we made a trio (electric guitar, drums and a small cheap electric organ) and we tried badly to play songs of Black Sabbath, Pink Floyd… in an attic. People in the village were complaining a lot!

What led you to start playing saxophone?

I came to live in Paris in 1970. I started attending a lot of concerts. Mainly modern jazz, free jazz. The first one was Steve Lacy. I was lucky enough to attend Sun Ra’s first Parisian concert (in a theater at Nanterre, a town very close to Paris) in 1972! Musicians of the Art Ensemble of Chicago were living in Paris… But I would have never played saxophone if I had not met a young saxophonist playing in the street. He was playing jazz standards, and I was fascinated. I talked with him, but I never saw him again. Anyway, the following day, I rented a tenor saxophone! It must be in 1975… Very soon, I quickly transcribed Lester Young’s solo on ‘I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance with You’. And I could play it, it was not too bad for a start…

Who would you cite as some of the main influences?

Of course I knew and listened to a lot of saxophone players. I got lessons with good musicians. They tried to teach me the chord changes. I was just happy to play, often alone. But I had no further idea, just trying to learn the basic things, and practicing, working on the scales. I couldn’t pretend to play like a jazzman, and I never wanted to. One of my favorite tenor saxophonists was Sonny Rollins, mainly what he did in the 50’s and the 60’s; I liked his sound and his phrasing. But there were many others I enjoyed too: John Coltrane of course, Dexter Gordon, Charlie Rouse, Johnny Griffin, Booker Ervin, Sam Rivers, Wayne Shorter, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young…

How did you start Axolotl? What was the initial concept behind the group? Where did members of the project know each other?

There was a key event; I want to refer to an important French jazz festival: Châteauvallon near Toulon (southern France), taking place in an incredible outdoor amphitheatre overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. I attended the first edition in the summer of 1972. Greatest jazz musicians played there. In the summer 1977 edition, I was there of course, mainly because there was a workshop directed by Steve Lacy. Etienne Brunet participated in this workshop too, and it was the first time we met. He was living in Paris too, and we kept seeing each other afterwards. He had created a duo called Axolotl with guitarist Marc Dufourd. Etienne invited me to join them. The idea was to improvise freely. It was a new concept to me: the very first time for me to perform free improvisation. It was a very exciting challenge of course: a new kind of personal and strong commitment. I already knew musicians like Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, John Stevens, Peter Brotzmann, Han Bennink, Fred van Hove, and the Rova Saxophone Quartet. I knew them through records we could buy in an amazing Parisian shop called Dolo Music and run by a great lady Dolores Cante (Jazz & Pop Center was the original name of this shop founded by a great producer, the late Gérard Terronès). At that time, there were some French musicians who were performing free improvised music too, such as Daunik Lazro who was playing in Saheb Sarbib group. He had a duet with Jean-Jacques Avenel too. All these musicians had a great influence on me. Etienne, Marc and I had a lot of discussions (including on the phone) about music, improvisation. We listened to records, we practiced a lot, and rehearsed a lot too. We frequently recorded these rehearsal sessions for critical listening. In September 1980, we started playing live as a trio in a great Parisian venue called 28 rue Dunois: three consecutive evenings! The trio Axolotl was launched!

How did you get signed to d’Avantage and what led to recording of your debut album in 1981?

We knew Jacques Berrocal very well. Etienne Brunet and Marc Dufourd had already played as a duo at the festival he managed: Sens Music Meeting. His label d’Avantage was important to us. When he kindly proposed to release our recording on his label, we were very happy.

Would you like to share some further words about the material on the debut album?

We had the opportunity to work with a great sound engineer who had already cooperated with Berrocal: Daniel Deshays.

How did you usually approach music making in Axolotl?

Talking a lot, and rehearsing. Listening to improvisers (records). Reading some info coming from the UK mainly. Marc subscribed to the British magazine Music. We have to remember that the Internet didn’t exist at that time. It was very difficult to establish links with other musicians.

“We were always questioning ourselves”

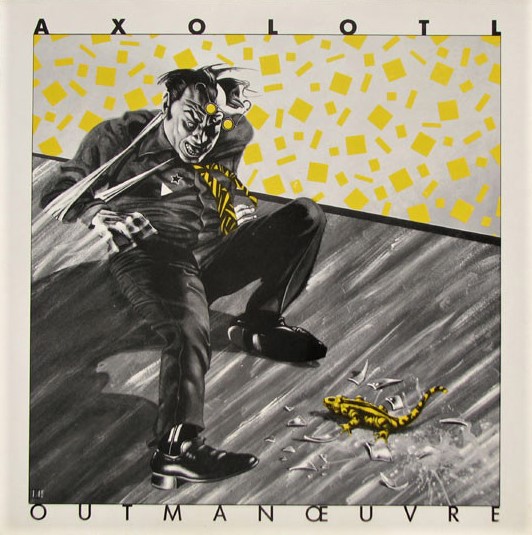

Your second album was released on Cryonic Inc, a label that also released Art Zoyd, Univers Zéro et cetera. What’s the story behind ‘Out Manœuvre’?

We felt that some new trends were emerging. I mean through musicians like John Zorn, Eugene Chadbourne, Bob Ostertag, Henry Kaiser, Alterations(Steve Beresford, David Toop, Terry Day and Peter Cusack). Ornette Coleman’s albums ‘Dancing In Your Head’ and ‘Body Meta’ were important to us too. We were also influenced by some pop/rock bands like Pere Ubu, James Chance, Fred Frith, DNA with Arto Lindsay. We were always questioning ourselves. We felt that electronic instruments were interesting. Marc used effect pedals with his electric guitar (flanger, et cetera). We were attracted by the drum machines too. We wanted to make something different from strictly acoustic improvisation.

Was there a certain concept behind it or was it a complete improvisation?

It was mainly improvised with some specific instructions.

Where did you record it?

Recorded in a house in the countryside.

Did you ever consider yourself as a part of the Rock In Opposition scene?

Absolutely not! I’m not sure I was familiar with this scene!

Did you play any shows? If so, where and with what other bands?

Axolotl performed quite a lot of gigs in France, and some abroad: Germany, Belgium, Italy. We made some concerts with Berrocal too.

What occupied your life after Axolotl?

For many reasons, I decided to give up playing music. But I stayed connected to improvised music and improvisers. I knew most of them, I used to attend gigs everywhere. An important new venue had arisen: Les Instants Chavirés at Montreuil (close to Paris). There were many festivals outside Paris: Musique Action at Vandœuvre (close to Nancy) run by the late Dominique Répécaud, Densités, Fruits de Mhère, Mulhouse. I even hosted a radio program (Radio Libertaire) for two years in Paris.

In 1997 you formed Potlatch, an independent label, working with significant performers of free improvised music. What was the main concept when starting a new label?

At that time I thought that some improvisers were under-represented, mainly among French musicians. So I vaguely felt the need to do something, but I didn’t know precisely how. Actually the arrival of the Internet triggered everything. Suddenly, there were many opportunities to reach lots of people concerned with the subject of improvised music. Such through mailing lists (Zorn list, Fennec list in France), boards (Jazz Corner at first, then Bagatellen, I Hate Music), blogs. I also understood that it was easy to quickly build contacts with distributors all over the world, including Metamkine run by Jérôme Noetinger. Same thing with journalists and magazines like The Wire, Revue & Corrigée. It was possible to build up notoriety through this new ecosystem.

How do you usually choose the artists?

Well, my own tastes of course. And the personal contacts I had with musicians. The first bunch of releases included Derek Bailey, Joëlle Léandre, Daunik Lazro, Fred van Hove, Michel Doneda. I also tried to select musicians who were not well known but who deserved wider recognition, as I did with Sophie Agnel, Frédéric Blondy, Christine Abdelnour Sehnaoui, Pascal Battus, Marc Baron, Dafne Vicente-Sandoval, et cetera. I always believed that a label can bring a musician some credibility. I think it worked that way with Stéphane Rives’ CD. He was not very well known at that time. I guess he gained some recognition with Fibres. Providing credibility was one mission statement for Potlatch. Musicians need that; they can’t get only with streaming. Quickly, I became more and more interested in the encounter between electronic and acoustic instruments. There are many examples in the catalogue. Kristoff K. Roll and Xavier Charles; Triolid; Evan Parker and Keith Rowe; Trio Sowari; Phosphor; John Butcher and Christof Kurzmann; Jean-Luc Guionnet and Toshimaru Nakamura; Pascal Battus and Christine Sehnaoui Abdelnour; Klaus Filip and Dafne Vicente-Sandoval; Bryan Eubanks and Stéphane Rives; Bertrand Denzler and Jason Kahn. I always thought that confronting electronics with reed instruments like saxophone was a big relevant challenge. I also like musicians who are obsessed with details. Originality and quality are often hidden in very small details. Bertrand Denzler’s solo album is a good example: from the very first minutes of tenor, there are some amazing tiny things. Same for the duo Jean-Luc Guionnet and Seijiro Murayama: listening to their music is like looking in a microscope; you see something and you open it, then you go into the details and you open that again and, very slowly, you go into more other details, deeper and deeper. In recent years, new trends of contemporary music drew the attention of improvisers by focusing on the importance of sound, textures, silence, microtonality, et cetera. In France there are a lot of musicians exploring these new directions. I am very close to Didier Aschour who created the group Dedalus; he also runs a great festival in Albi (south-west of France). I’ve worked with American composer Michael Pisaro, French composer Pascale Criton, and with the Onceim: a large orchestra with classical musicians and improvisers, and run by Frédéric Blondy. They played last year at the Berlin Philharmonic!

Do you also organise gigs?

I happened to recommend some musicians to Les Instants Chavirésa a couple of times. I helped Marc Fèvre/Atelier Tampon to organize some gigs several times too. His work has been decisive in the events of the Parisian scene in recent years. And he introduced us to natural wine!

What else currently occupies your life?

I have a very conventional life. I have some interests besides music: cinema, swimming, politics and geopolitics, watching sport and news on television.

What are some future plans for you?

Nothing special. Nothing important.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

In traditional jazz, I like Sonny Rollins phrasing. But I was not influenced, because, for me, it was impossible to do that. If we consider free improvisation, I was influenced by Evan Parker. I think he took Coltrane’s language to the extreme. But, fortunately, it was impossible to play like him too. Actually, when I was playing saxophone during these years, I think that the main thing for me was practicing the instrument the more I could.

Klemen Breznikar

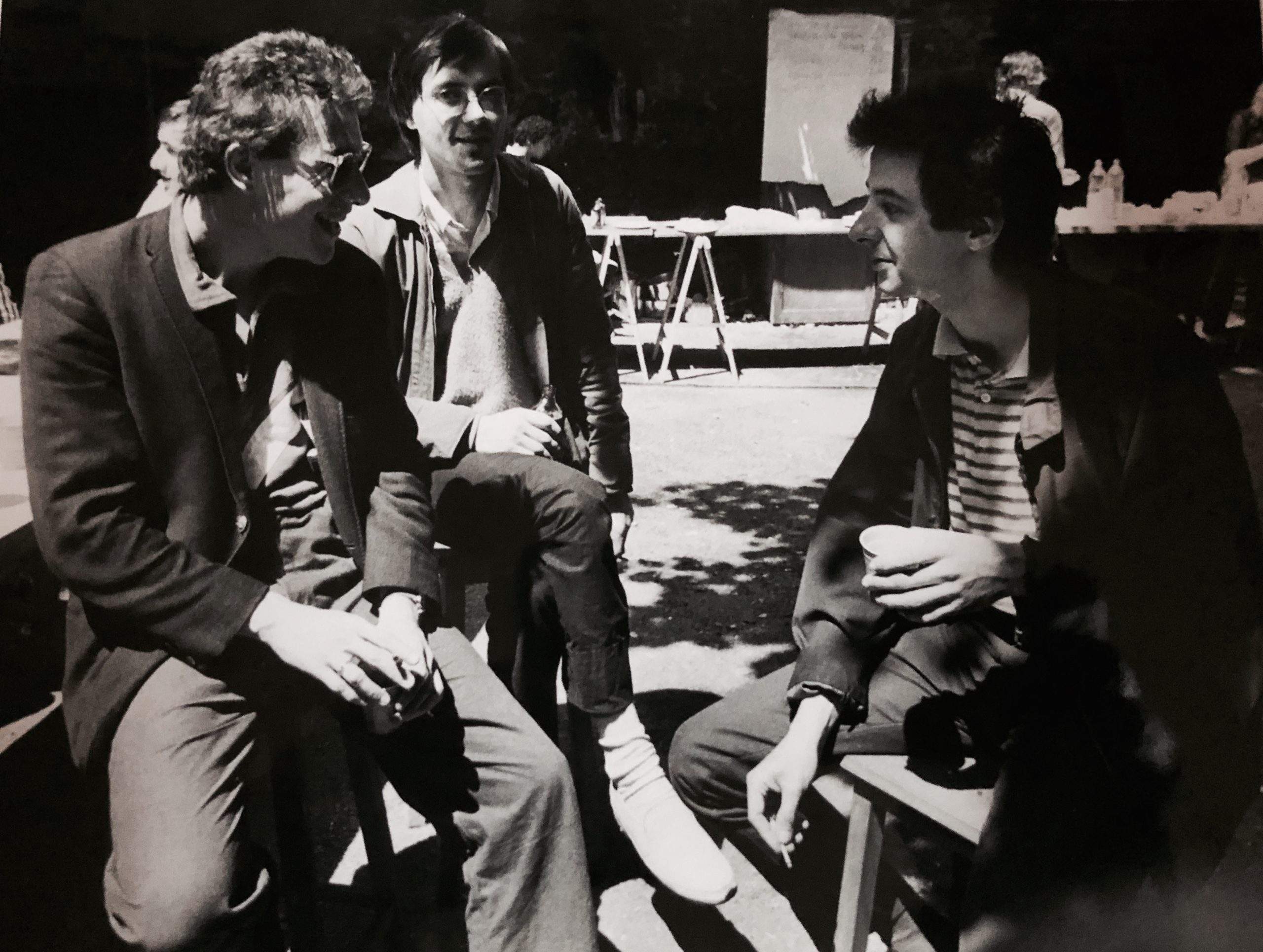

Headline photo: Axolotl in 1983 | Photo by Annie Trezel

Potlatch Official Website / Facebook

SouffleContinu Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

Axolotl | Etienne Brunet | Interview

Good to see another interview on Axolotl; “Outmanoeuvre” is one of the best Experimental recordings.