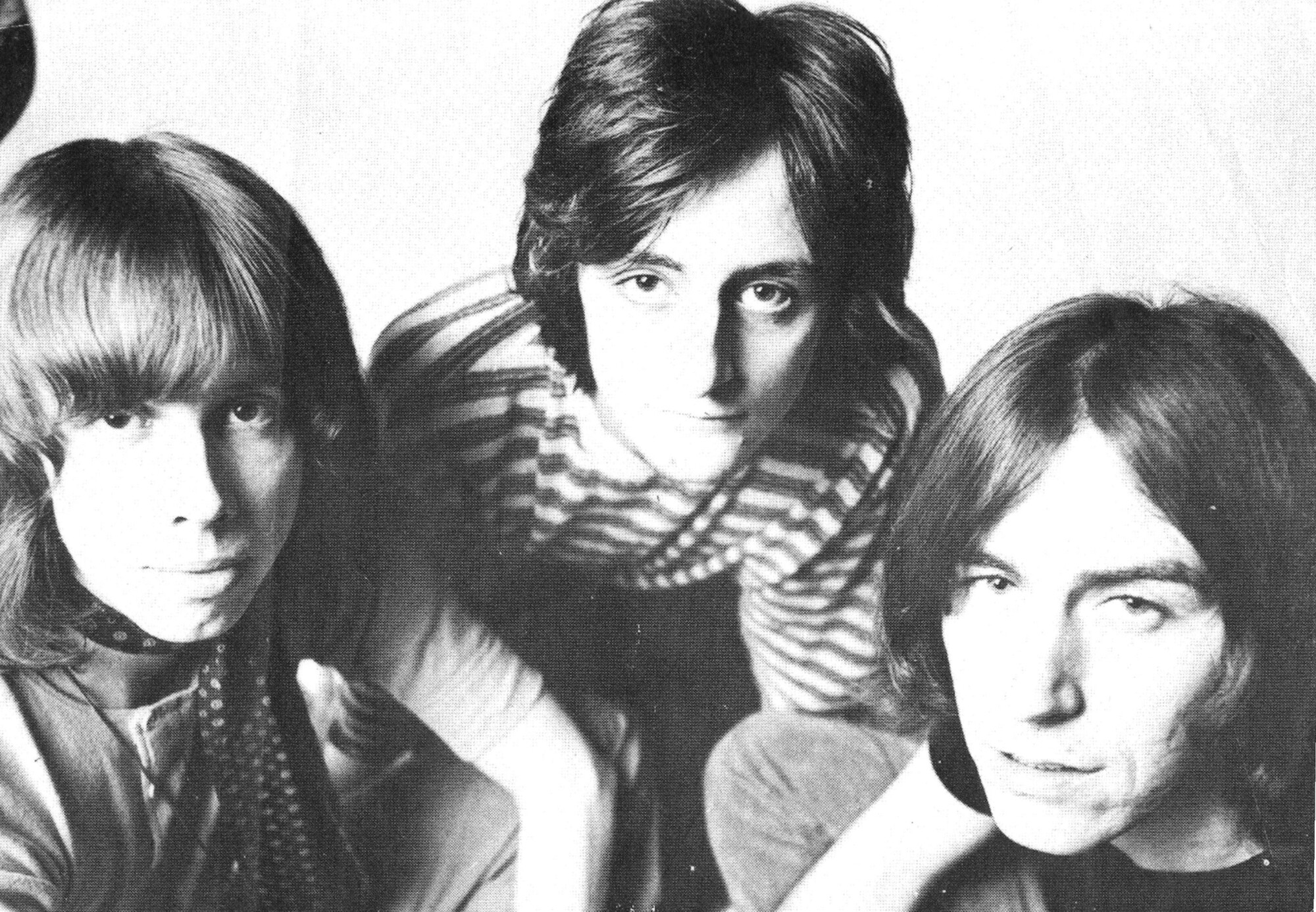

Synanthesia | Interview | “Underground Acid-Folk Gem”

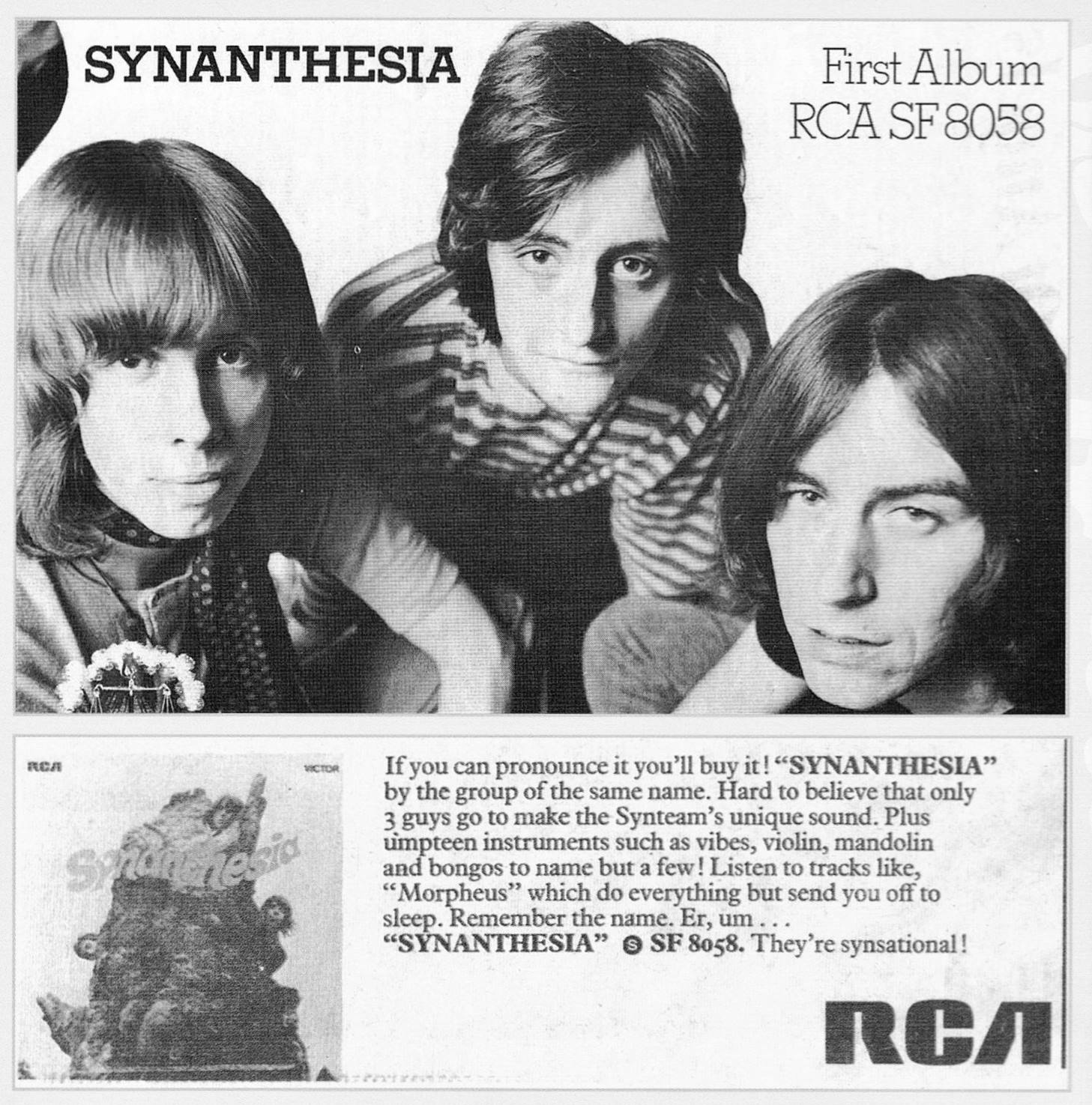

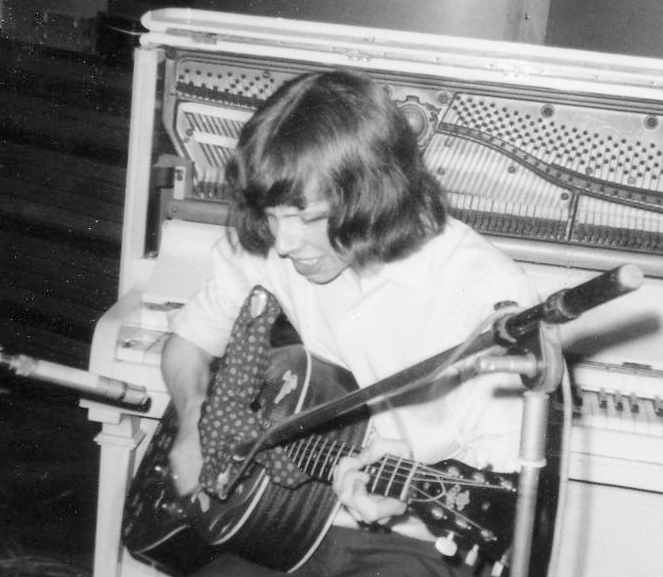

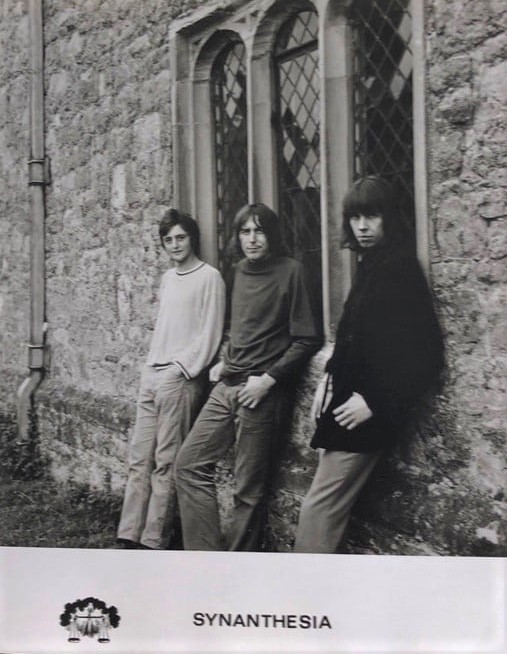

Synanthesia formed thanks to a Melody Maker ad placed in 1968 by guitarist/vibes/vocalist Dennis Homes, answered by Jim Fraser (who played sax, oboe and flute) and Leslie Cook (an Incredible String Band fan on bongos, violin and mandolin).

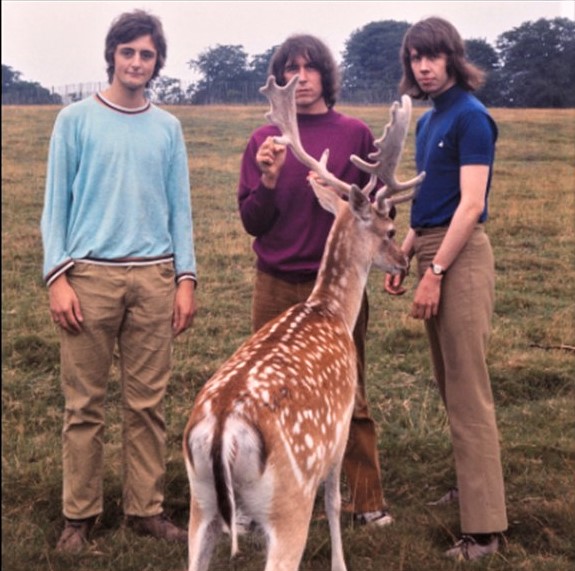

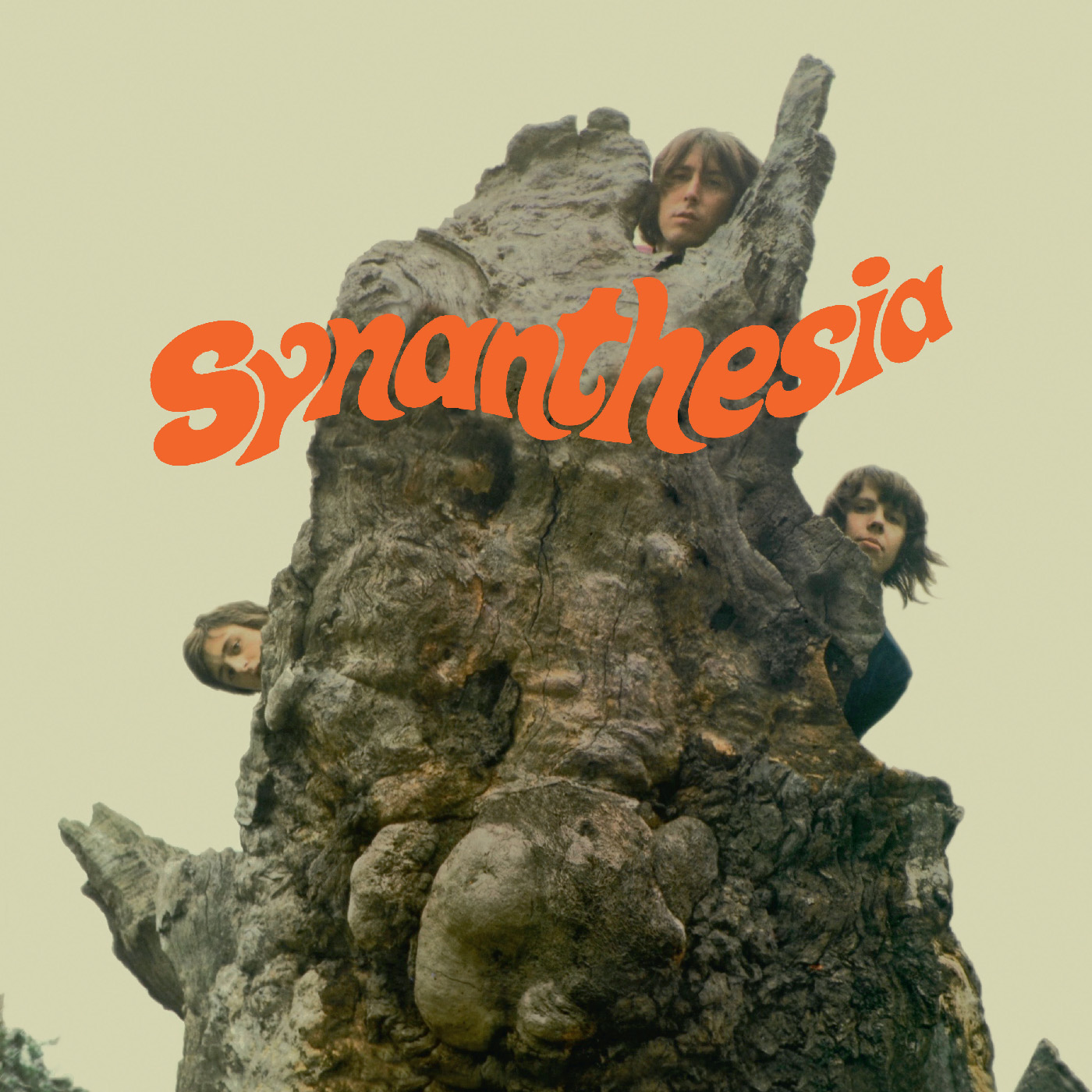

With their particular blend of folk, jazz and psychedelia, the trio played all the key underground venues and clubs, sometimes alongside top acts like Pink Floyd, King Crimson or Fairport Convention. Their sole album was recorded at Sounds Technique studio in Chelsea (which was where Pink Floyd were recording their albums at the time) and subsequently released by RCA. The cover featured the trio climbing onto a tree at the same park where the Beatles filmed their “Strawberry Field” promo film. Despite the good reviews and the support of DJs like John Peel, the album was considered too far out and psychedelic and eventually flopped, only to be re-discovered several decades later by acid-folk fans and collectors.

“Our combined musical landscape opened up a whole range of possibilities”

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

Dennis Homes: I was born in 1947 and grew up in the East End of London, a very working-class area that had been heavily bombed during World War II. As a kid bomb-sites were my playground! At family get-togethers some of my relatives would knock out a tune on the piano. None of them were musically trained, they just played by ear. I guess it was in 1956 when rock ‘n’ roll records were starting to be played on the radio that music really started to hit me. As a nine-year-old I loved listening to Elvis Presley, Fats Domino, Little Richard, et cetera.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

When I was 13 my grandmother gave me a rather old battered ukulele banjo that had been in the back of a cupboard for years. It has belonged to one of my uncles from just before the war. I went along to a local music shop and bought some new strings and a couple of teach yourself the ukulele books. I learn the chords for a few songs such as ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Clementine,’ ‘Red River Valley,’ et cetera. It got me quite interested in playing music, but I didn’t think that a ukulele was a particularly cool instrument. It was old fashioned and I really wanted a guitar and to play some rock ‘n’ roll songs. The following Christmas, when I was 14, my parents bought me a small Spanish guitar and that really started my musical journey.

What bands were you a member of prior to the formation of Synanthesia?

At the age of fifteen I really wanted to play in a band. I often played with other school friends who had guitars but none of them were as serious about it as I was. In those days there was no YouTube or videos to teach would-be musicians technique, just books. I started going around London clubs that had live bands and closely watching the guitarists. One club was called Studio 51 which was a tiny basement room beneath an office in Great Newport Street, close to Leicester Square in London’s West End. Every Sunday afternoon they used to have rhythm & blues bands playing there from 3 pm until 6 pm. All the bands were unknowns.

Then one afternoon in April 1963 they booked a new band called The Rolling Stones and as usual I went along to see them. The room was quite small and I guess that there were only between twenty to thirty people in the audience. There was no proper stage, the band were at the far end of the room. Keith Richards, Brian Jones and Bill Wyman were all sitting on stools, as was the pianist, Ian Stewart. Mick Jagger just stood in front of the microphone, no dancing or “move like Jagger” moments! I was most impressed and my first impression was that they really had got the Chuck Berry sound off perfectly. I then started to see them every time they played at the club and over the weeks the size of the audience grew and grew. Even though they had not made a record or been on TV or radio they started to build up a reputation by word of mouth among the kids in London. They really had a big influence on me at the time.

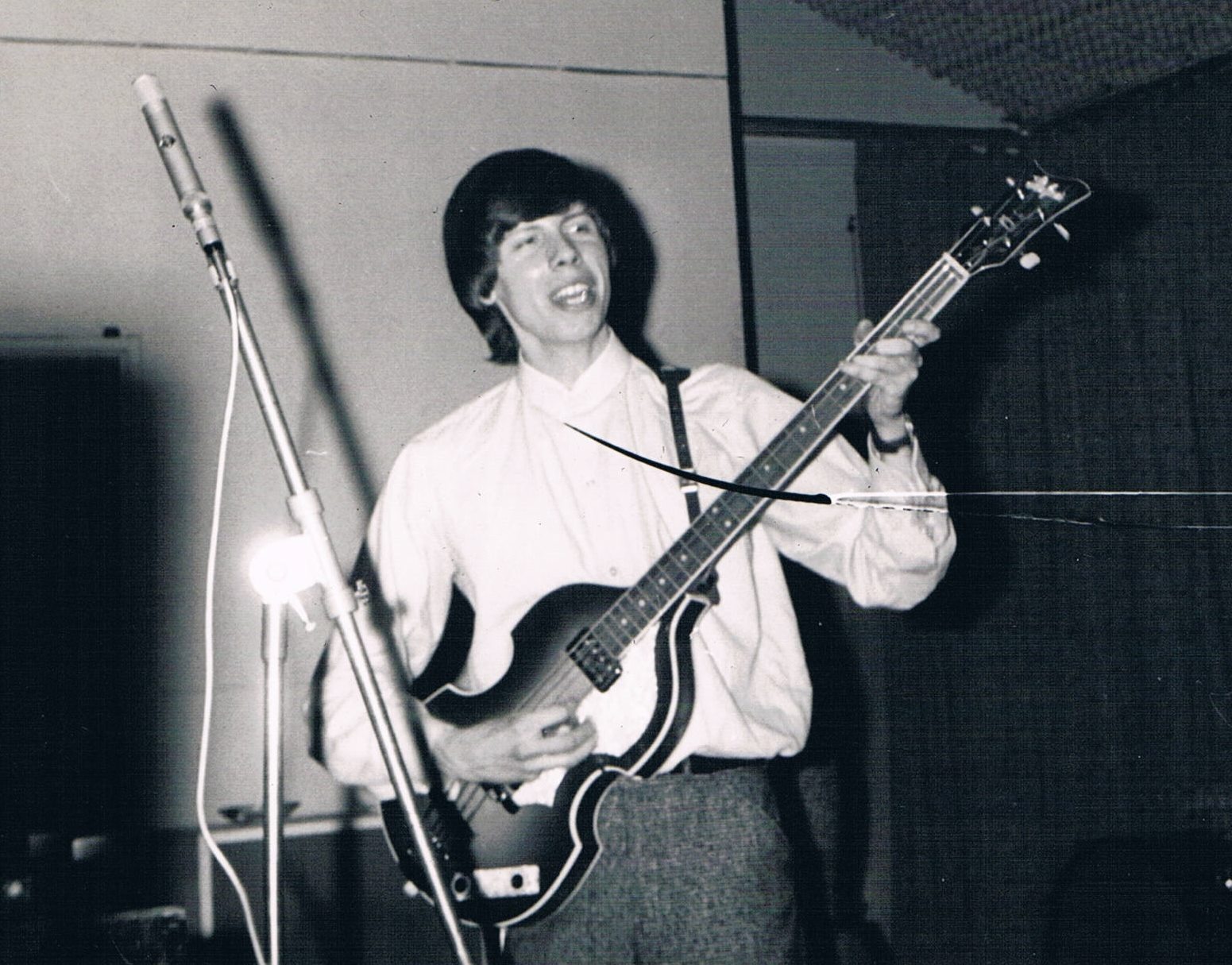

I was eager to join a band and in the weekly music magazine Melody Maker there were loads of adverts from bands seeking musicians and musicians seeking bands. Being fairly new to playing guitar I was definitely not good enough to play lead guitar and there were so many adverts from rhythm guitarists seeking bands. However, there were lots of bands seeking bass guitarists, but not many bass guitarists seeking bands. I therefore thought that my best way to get into a decent band was to take up bass guitar. I bought myself a bass guitar and amplifier, a few books on playing bass and spent countless hours at home on a crash course to learn the instrument as quickly as possible and my first band was The Ricochets.

What kind of music did you play with The Ricochets?

We mainly played rock ‘n’ roll. Loads of Elvis Presley’s songs as the lead singer Kenny Starr could really sound like Elvis. We also did Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent and other rock ‘n’ roll material. We also threw in the odd Beatles and Rolling Stones song.

You mostly played in clubs around North and East London. Tell us more about the lineup and the songs you were playing…

We mainly played in pubs. The pub scene was very big for groups back in those days. We played three or four times a week. The original line-up was lead, rhythm and bass guitar, drums and tenor sax. We later added an organ.

The Ricochets started in 1964, but in 1966 the rhythm guitarist, sax player and organist left. We then brought in another tenor sax player plus another guy on baritone sax who also doubled on flute and we became a soul band. The new band was called The Kalvin Starr Movement and we played lots of Otis Redding and American soul material.

How did The Inhibition come about?

In 1967 I wanted a change. The Inhibition were a more earthy rock and soul band consisting of three guitars and drums. The bass player had just left the band so I joined them.

“I wanted to explore new sounds”

How do you recall the period when psychedelic music became more and more influential? I guess you were all influenced by early Pink Floyd and Soft Machine?

The Inhibition were a great group but I was still looking for something different musically, I wanted to broaden my horizons. While playing with The Kalvin Starr Movement I also took up playing the vibraphone as I thought I could use it occasionally in some soul ballads as a vibraphone was often used in some Tamla Motown songs. But the band wanted me to just stick with playing bass guitar as did The Inhibition. In my head I wanted to explore new sounds.

When we weren’t playing gigs I would often go alone to some of the London clubs and listen to new music. I’d go to places like Middle Earth which was very psychedelic where Pink Floyd would regularly play. But I’d also go to modern folk clubs such as Bunjies and Les Cousins where Bert Jansch and the Incredible String Band would play. So two very diverse musical genres influenced me at the same time; psychedelic rock and modern off-beat folk music.

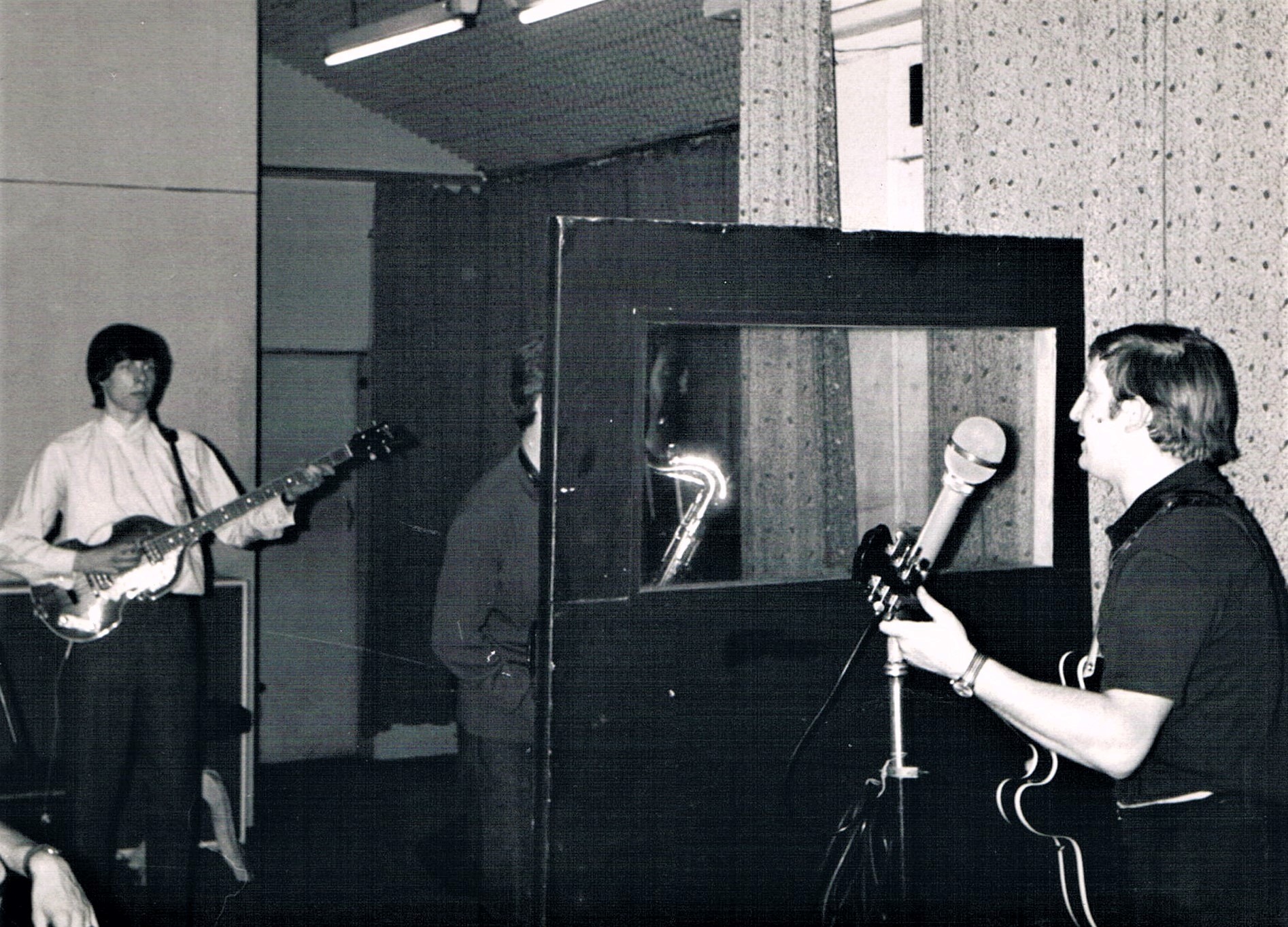

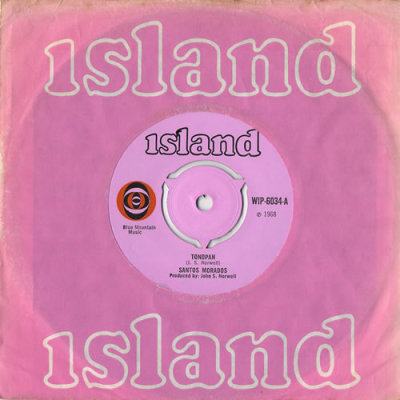

In early 1968 The Inhibition were signed up by a record producer and released a single on the Island label called ‘Tonapah’.

The lead singer of The Inhibition, Henry Buckle, had a tremendous soul voice and was also quite a good songwriter. We made a few demos and our booking agent played them to a songwriter who was looking for someone with an earthy soulful voice to record one of his songs. He really liked Henry’s voice and decided to use him to add vocals to ‘Tonapah’. The backing track was already pre-recorded by session musicians so the rest of the band weren’t needed for the A side. We played on the B side on a song called ‘Anything’ that the songwriter had written. We were also joined on that recording by the pianist the late Nicky Hopkins who was one of the top rock pianists around having played on recordings for The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, The Who, The Kinks, Jefferson Airplane, et cetera.

This whole thing totally pissed me off. ‘Tonapah’ was an OK song, but nothing special. I thought that both Henry and myself had written better songs. The B side ‘Anything’ was nothing more than a twelve-bar blues song with rather inane lyrics. Without even informing us the songwriter had the song released on the Island label and decided to change the name of the band. At first he called us Henry and the Hobo Amigos, but then at the last minute decided to call us Santos Morados. When the record was released they even got the title of the B side wrong. Instead of putting ‘Anything’ or the label they put ‘Anytime’!!! I then decided to quit the band and began writing lots of songs with the idea of forming my own band.

Around this time you decided to start your own band. Can you elaborate the formation of Synanthesia?

With the previous bands that I’d played in we did the occasional self-penned song but the vast majority of our repertoire were simply cover versions of other people’s songs. I felt that we were nothing more than a live juke box and I so wanted to create our own music and write our own songs. Psychedelic bands and folk influenced acoustic music were both influencing the songs that I was writing. Having recently bought Donovan’s double album ‘A Gift from a Flower to a Garden’ I particularly liked the way Harold McNair’s jazzy flute playing mixed so well with Donovan’s acoustic guitar playing on many of the tracks. I also thought that a jazzy style flute would go so well with some of the songs that I was writing.

Throughout 1967 I had been learning to play the vibraphone. I took lessons from a vibraphone player/percussionist in the pit orchestra of Her Majesty’s Theatre, Haymarket in the West End of London. Fiddle on the Roof had recently opened there and I used to go for lessons there early evening before the show started. The guy, like quite a few in the pit orchestra, was a keen jazz man, but could earn far more money playing in the orchestra of a West End show than he could playing at a small jazz club. As well as vibraphone technique, he also taught me a lot of musical theory. In the past I just worked things out by ear from listening to records.

As well as working with a flute player I also thought that it would be great if I could team up with a like minded singer/guitarist and add vibraphone to his songs. This then was my original idea; a trio of two acoustic guitars and a flautist with me occasionally playing the vibraphone.

It was in June 1968 that I placed an advert in Melody Maker for a flautist and an acoustic guitarist to join me in forming a trio playing original music. Even before the magazine came out I received a phone call from Les Cook. He actually worked in the ad department of Melody Maker and lived not very far from me. He told me that he played guitar and also wrote songs. He had never played in any band but sometimes collaborated with a friend, Richard Carlton, and wrote a few songs with him. He was firmly folk music based. Once the ad came out I received a call from Jim Fraser, who came from Bolton in the North of England but was now working in London as a heating engineer. I rented a small room in a local community centre and the three of us met up. I then found out that Jim Fraser was a keen jazz musician and had played in various bands in and around the Manchester area. His main instrument was an alto sax but also played soprano sax, concert flute, alto flute and oboe. I then discovered that Les Cook also played mandolin and violin. With me also doubling on vibraphone this opened up a whole range of possibilities that I did not originally envisage. With Les having a folk music background, Jim being essentially a jazz musician and me from a rock background our combined musical landscape opened up a whole range of possibilities.

It didn’t take us very long to build up a repertoire, just a few weeks. I’d play one of my songs and the other two would pitch in their ideas. Les would play one of his and Jim and I would offer our ideas. Despite our totally diverse musical backgrounds ideas came thick and fast and they really seemed to work.

I really wanted to play in front of a live audience and see their reaction so I contacted a local folk club and asked if we could do a half hour spot for free.

I didn’t know at the time that this was a very traditional folk club and the audience looked quite dumb struck by our performance. In one song Jim played a wild jazzy solo on flute while at the very same time stuck a small African wooden flute up his nose and played both flutes together. The audience thought we were crazy!

How did you decide to use the name “Synanthesia?”

It’s the name of a tune by the American jazz musician Cannonball Adderley and means a mixture of senses.

The material you composed was highly original. What can you tell us about the song writing process?

Both Les and I wrote songs and between the three of us we would start adding ideas for the arrangement. Because of our totally different backgrounds we ended up with rather unusual arrangements which I guess gave us a very original style.

You played all around the country, would you like to recall some of the clubs and groups you shared stages with?

We mainly played on the university circuit. We also played at the Marquee Club in London which during the 60s and 70s was regarded as the top club in the country where all the top bands played such as The Rolling Stones, The Who, David Bowie, et cetera. We also played at Mothers in Birmingham which was the top club in the Midlands. We also played in London’s iconic folk venue Les Cousins.

We played on stage alongside Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span, Pink Floyd, The Foundations, King Crimson, The Edgar Broughton Band, The Herd (which included Peter Frampton at that time), Bonzo Dog and the legendary American Bluesman John Lee Hooker.

How did you get signed to the RCA label that led to the release of your sole album?

The record producer Sandy Roberton of September Productions heard us and offered us a record deal. We had only been gigging for about six months. He was also recording Steeleye Span at around the same time and was releasing his albums on RCA.

You also recorded a track called ‘Shifting Sands’, but it never got released as a single. Why is that?

After the album was released Sandy Roberton wanted us to release a single. He had heard me play ‘Shifting Sands,’ which I wrote, and thought that it had a slightly more commercial sound to it and would possibly get more airplay. To make it more appealing to radio DJs he thought that an orchestrated string section should be added. For this he listed David Palmer who was soon to be the keyboard player in Jethro Tull. He was classically trained and Jim and I worked with him and he came up with the orchestral score.

Les Cook, having worked at Melody Maker, wanted to be a journalist. He embarked on a journalist course but was getting nowhere due to all the gigs we were getting so decided to leave the group and this was the end of Synanthesia. The band lasted just 18 months. ‘Shifting Sands’ was never released as a single. but was included on an RCA compilation album called ’49 Greek Street’ featuring acts that had played at the legendary Les Cousins club. In 2006 when Sunbeam Records re-released the Synanthesia album as a CD they included ‘Shifting Sands’ on it. Sunbeam Records also released a compilation CD of acid folk acts and ‘Shifting Sands’ was the title track.

What influenced the band’s sound?

We each had our own personal musical influences but as a band we were influenced by each other.

Did the size of audiences increase following the release of your debut?

Not really.

What’s the story behind your debut album? Where did you record it? What kind of equipment did you use and who was the producer? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

We recorded the album at Sounds Technique Studio in Chelsea. It was a major studio where Pink Floyd, Elton John, Fairport Convention, Jethro Tull, The Who, The Yardbirds and Nick Drake recorded all their early stuff. Sandy Roberton was the producer and Victor Gamm was the engineer.

Please share your recollections of the sessions. What were the influences and inspirations for the songs recorded?

The whole album was recorded in just a couple of days. Very little over-dubs. All the songs were from our live stage performances.

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

‘Minerva,’ ‘Morpheus,’ ‘Fates,’ ‘Vesta’, ‘Mnemosyne’ and ‘Aurora’ were all part of a song cycle we performed in our act. They were all Greek Gods and we used what each one stood for as a starting point for a musical exploration. ‘Peek Strangely And Worried Evening,’ ‘Rolling and Tumbling,’ ‘Trafalgar Square,’ ‘Just as the Curtain Finally Falls’ were all just songs we played at gigs. My own personal favourite on the album is ‘The Tale of the Spider and the Fly’. This song just builds and builds very slowly.

What can you say about the cover artwork?

When The Beatles recorded Strawberry Field Forever they put out a promotional film for it, (they weren’t called videos back in those days!) It was film In Knole Park in Sevenoaks, Kent. They wanted something really weird and psychedelic and decided to have The Beatles wreck an old piano up a tree (!!!). At first they found an old dead tree but then decided to use a living tree that was almost adjacent to the dead tree. If you go onto YouTube and search Strawberry Fields Forever by The Beatles you will see this weird film.

Anyway, when RCA were going to release the Synanthesia album they wanted a slightly odd cover. The photographer had been on the Strawberry Fields filming shoot so took us back to Knole Park, found the dead tree and got us to climb it and that is the cover. About 45 years later I happened to be in the Sevenoaks area so decided to visit Knole Park and see if the tree was still there…and it was. So here I am on the same tree 45 years later!

How many copies of the album were pressed in your opinion?

I don’t know.

Were you inspired by psychoactive substances like LSD at the time of writing the album?

No.

How pleased was the band with the sound of the album? What, if anything, would you like to have been different from the finished product?

Because it was done almost like a live recording with very little doublet tracking the finished work was very much how we sounded playing live gigs. If we had spent a little more time on it I think that we could have given it a lot more polish; but there again it would not have a true reflection of our live sound.

Was there a certain concept behind the album?

Not really.

Are you excited about the upcoming Guerssen reissue? Would you like to share a bit more about the source for the reissue? Is it from the original master?

When the album was first released John Peel and Tommy Vance were the only radio DJs to play tracks. It was too weird and not commercially pop orientated for others when kids who weren’t even born when the album first came out started to take an interest in it and old copies started to sell for huge amounts (around £250) on eBay. Sunbeam Records did a re-release on CD in 2006 and it sold quite well. Since then tracks from the album have been included in six different compilation albums. I am pleased that Guerssen Records are re-releasing it as a vinyl LP.

What happened after the band stopped? Were you still in touch with other members? Is any member still involved with the music?

Jim Fraser moved to Spain and for quite a while played in various jazz combos, Les Cook moved to the Netherlands and started his own business and only played as a hobby.

You carried on a career playing at folks clubs, mostly solo but occasionally with other musicians.

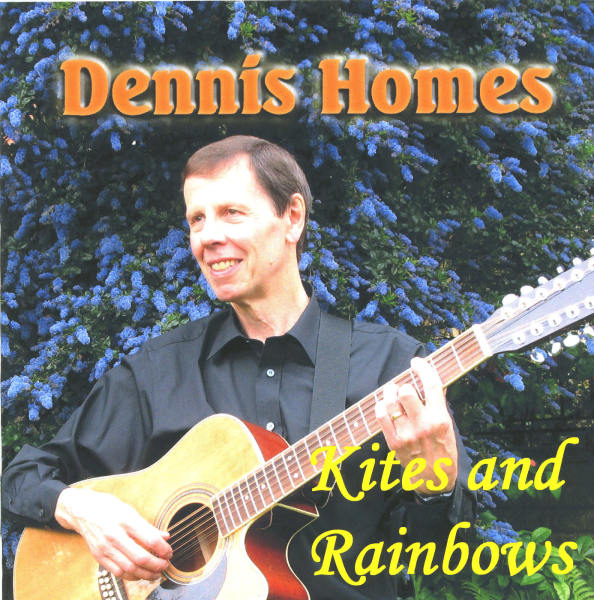

In the early seventies I became involved with a few theatrical groups and wrote some music for a few productions. I then teamed up with a playwright and wrote a dozen songs for a musical revue called East of Aldgate Pump which was staged in London at the Hoxton Music Hall. Then throughout the late seventies and throughout the eighties I stopped performing and just played as a hobby. Then in the early nineties I started writing lots more songs and began playing gigs and I’m still doing it now. In recent years I’ve recorded three solo albums.

What’s the story behind a club you started called The East London Arts Lab where musicians, singers, poets, and actors could perform?

In the early seventies there were quite a few mixed media clubs and I decided to start one in East London. It ran for about a year and it was that which got me interested in the Theatre.

What occupied your life after that? You got back to music in the 90s, if I’m not mistaken?

Always took a great interest in music of different genres but wasn’t particularly interested in gigging at that time.

You have over 400 songs under your belt, that’s truly impressive. Can we expect something new?

I’m always writing songs, it’s closer to 600 songs right now.

Tell us about your three solo albums, ‘Kites and Rainbows’ (2008), ‘We May Never Walk This Road Again’ (2014) and ‘Sunset to Song Rise’ (2017).

They are all songs that are now in my current repertoire. I hope to record another album next year. ‘Sunset to Song Rise’ is still available on Amazon and Apple iTunes.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band?

Probably our performance at the Marquee was the best. The venue was packed solid and the audience was great.

What are some of your favorite memories from Synanthesia and the 60s in general?

It was great just going on stage and performing. Although the Vietnam war was, we really thought that our generation would be the one to change things. Bob Dylan’s ‘The Times They Are A-Changin” was our anthem. Flower Power, Peace and Love is what we were standing for. Sadly, nothing has changed and war and hate still rages.

Is there any unreleased material by Synanthesia?

No.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you. Music is what can unite us all.

Klemen Breznikar

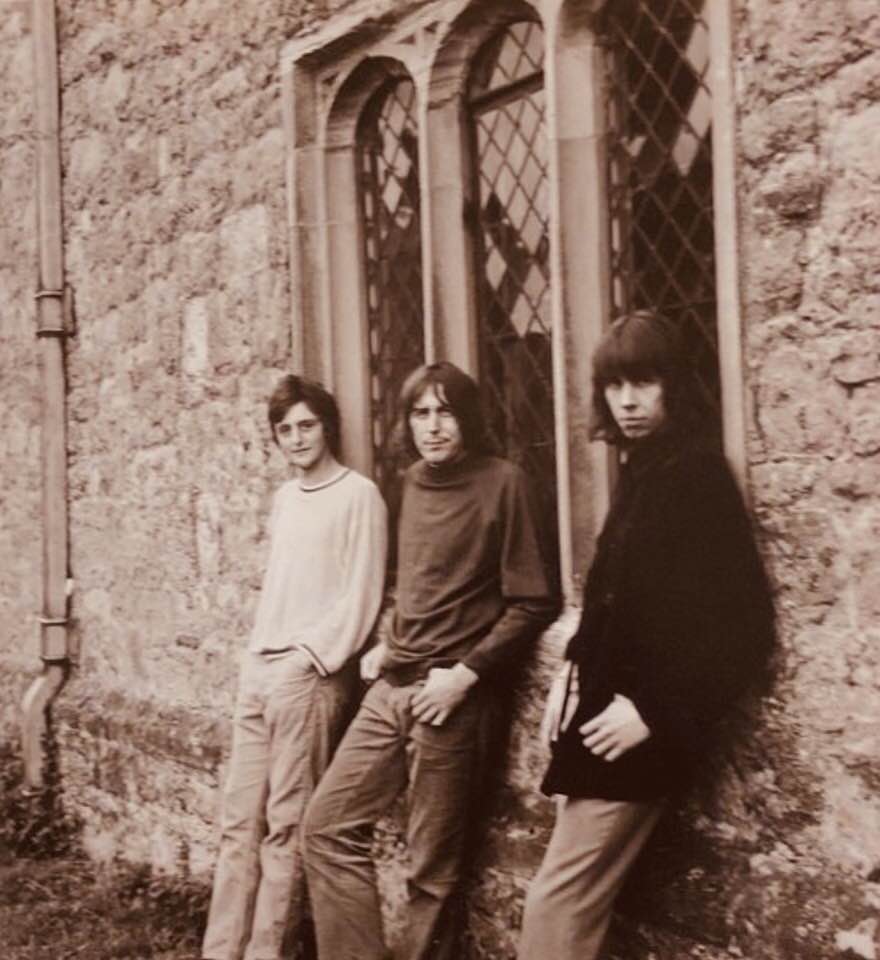

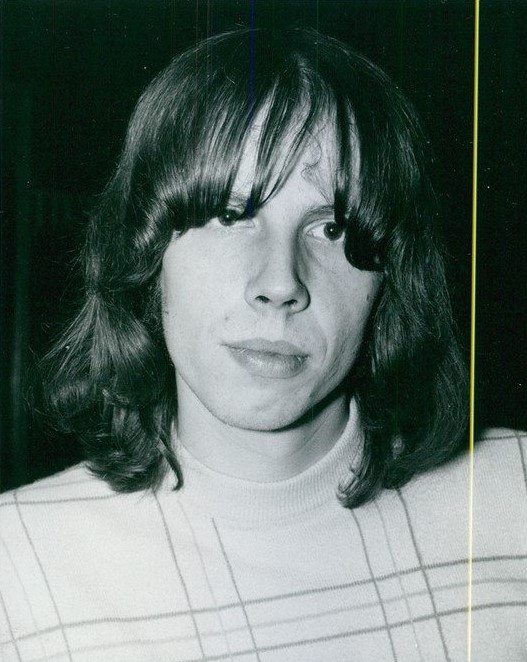

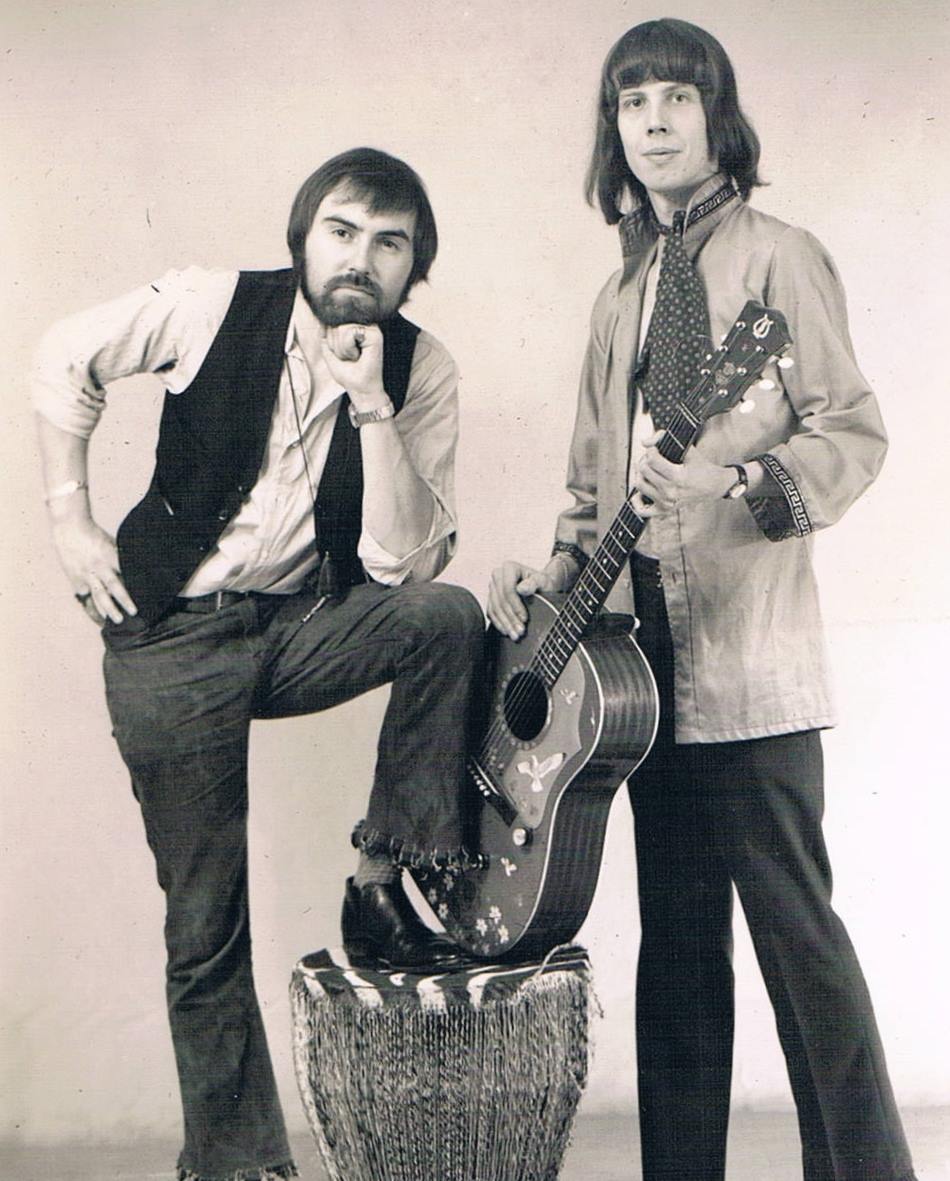

Headline photo: Synanthesia | From left to right: Dennis Homes, Leslie Cook, Jim Fraser

Dennis Homes Official Website

Guerssen Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube