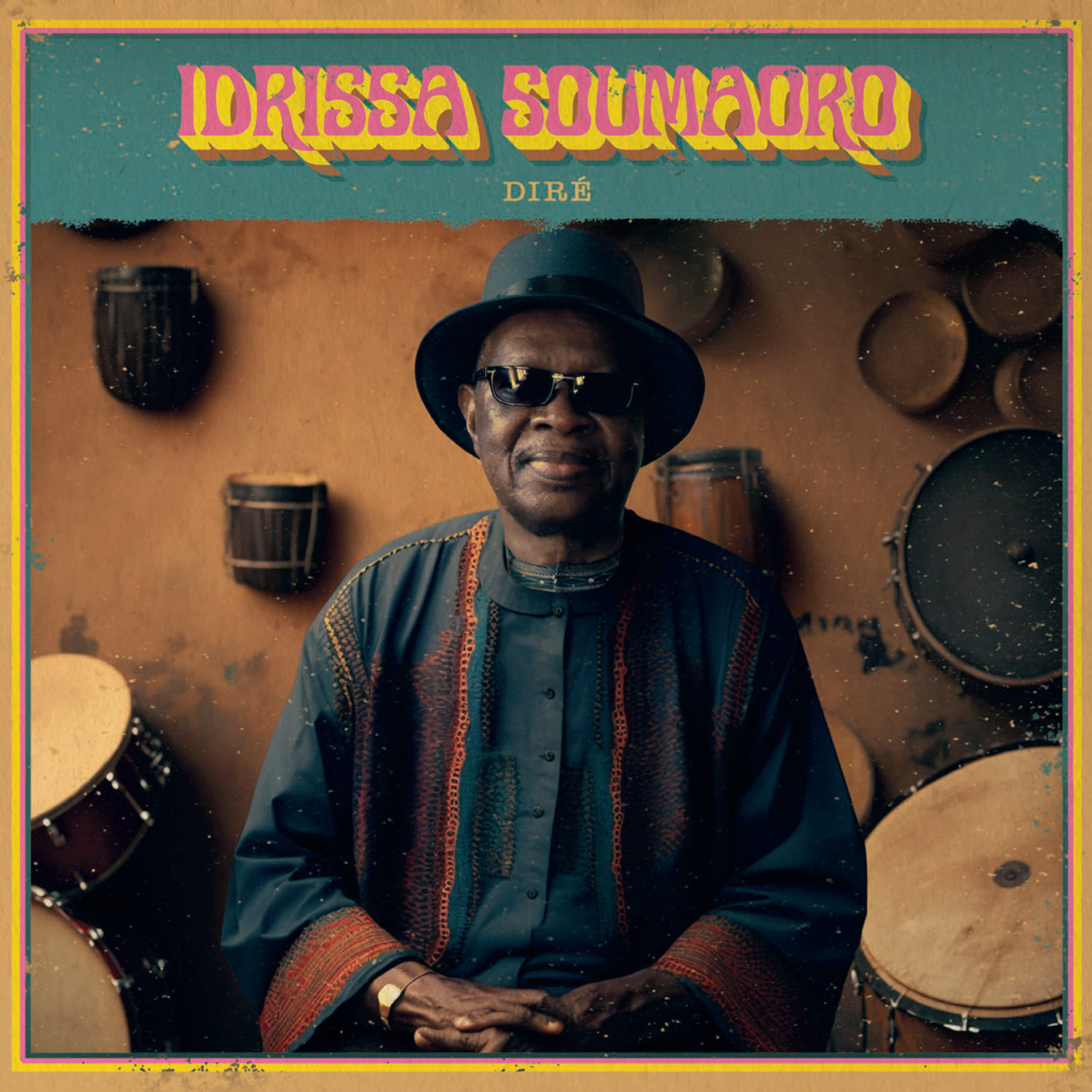

Idrissa Soumaoro | Interview | New Album, ‘Diré’

Legendary Malian composer, singer, guitarist and master of the kamalen n’goni Idrissa Soumaoro will release his new album ‘Diré,’ out September 22th, 2023 via Mieruba.

‘Diré’ is a beautiful collection of songs named in honor of the town where he met his wife and where his first daughter, who is no longer with us, was born. In 1971, after his studies at the INA in Bamako, Idrissa was transferred to Diré to teach music at the lPEG (Pedagogical Institute of General Education). He was 22 years old when he arrived in Diré. Idrissa has always been nostalgic for this beautiful place in the 333 Saints of Timbuktu region. As Idrissa sings in ‘Diré taga’ (Going to Diré), the track that opens the album, the city evokes deep emotions for the artist, as if it were a long-lost friend or lover. Celebrating the memory of the city of Diré leads the artist to retrace stories and lived situations that marked and animated him in years gone by: “I really miss the people, the colleagues, the friends and that period. Despite the time that has gone by, I would ardently wish to see Diré again.”

Today, at the difficult time Mali is experiencing, remembering the city of Diré in the 1970s also means for the artist not giving up hope for peace: “The memory of Diré, a beautiful town in northern Mali, strengthens my hope for peace, union and real independence for the happiness of my people’; as he sings in ‘Sababou,’ “Without hope, there is no life. Together we will succeed.”

The ten highly original compositions of the album are based upon traditional music of Mali, but Idrissa’s life experiences, travels, education, collaborations and personal musical career have led him to compose and perform music with other influences. As Idrissa says: “My inspiration generally comes from the donso n’goni, a Bambara instrument played by and for hunters throughout Mali. This is a pentatonic instrument, similar to the blues exported to the Americas by black African slaves. I’ve also spent so much time playing a variety of music that my music also reflects rumba, salsa (as well as Bamanan blues and a few derivatives: jazz, country, soul, rhythm and blues) et cetera. I have looked for and hope to have found my own form of expression from these influences.”

Throughout the album, his strong, clear voice sings in French, Bambara and English. It rides seamlessly upon a complex rhythmic sea of distinctly West African stringed instrumentation and percussion with accents of flute and balafon.

The album already has a long history: it was initiated in 2012 by Marc-Antoine “Marko” Moreau, former producer and manager of Amadou and Mariam. Moreau had plans to produce the album and invited Idrissa Soumaoro to start recording in Manjul’s studio in Bamako. When Moreau suddenly passed away, work on the album was still missing. The pandemic still added time for the production to continue. With the help of Climax Orchestra, arrangements and orchestrations were finalized in France.

Idrissa Soumaoro was born in 1949 in Ouéléssébougou, a small town 75 km south of Bamako in Mali. His brother-in-law, with whom he discovered his first modern guitar, was the headmaster of the primary schools he attended. Little Idrissa fell in admiration of the qualities of this outstanding teacher, who would in influence his professional future. During his school holidays in Bamako, Idrissa would wander around with his friends in lively places like the bus station and the area around the cinema. Enthralled by this urban hustle and bustle, the young rural boy discovered and was charmed by instruments such as the harmonica, the flute and the timbo. Back in the village after his holidays, he borrowed his brother-in-law’s guitar and tuned it to the sound of the ngoni. Between the ages of fifteen and sixteen, while he was preparing for his basic school-leaving certificate, Idrissa formed his first group, Djitoumou-Jazz de Ouéléssédougou, and every Saturday night he played at the local dust ball, which soon became the main event for the whole region.

In 1968 he entered the Institut National des Arts in Bamako and during his studies he recorded songs for ORTM Télévision nationale. It was during this period that he wrote his song ‘Ancien combattant,’ which was later covered by the Congolese artist Zao. After graduating from the National Arts Institute in Bamako, he became a teacher in Diré, then in Bamako.

A teacher by day and an artist by night, Idrissa continued to perform on various music stages, eventually joining the Ambassadeurs du Motel alongside Salif Keïta and Kanté Manfila, and befriending the blind Amadou Bakayoko. In 1978, following the break-up of the legendary Bamako band, he asked to be seconded to the Ministry of Health, with the idea of going with Amadou Bakayoko to provide musical support for students at the Institut National des Aveugles in Bamako and to raise public awareness of the need to empower the visually impaired. In the early 1980s, he set up an orchestra called “Eclipse” because the group was made up of sighted and blind people (like light and darkness, like the duality that makes up the world). In 1983-84, the sighted members left the group and it took the name “Miriya” (thought in Bambara): the place was left exclusively to blind musicians and singers led by Amadou and Mariam as lead singer. In 1984, thanks to this initiative, he was awarded a scholarship to study Braille musicography at Birmingham University.

When Idrissa Soumaoro returned to his native Mali in 1987, in addition to his university degrees, he had the Elisabeth Williams Prize from the Royal National College and Academy of Music for the Visually Impaired in Hereford in his briefcase. He held various positions of responsibility before being appointed Inspector General of Music at the Ministry of Education in 1996, a post he held until his retirement in 2011.

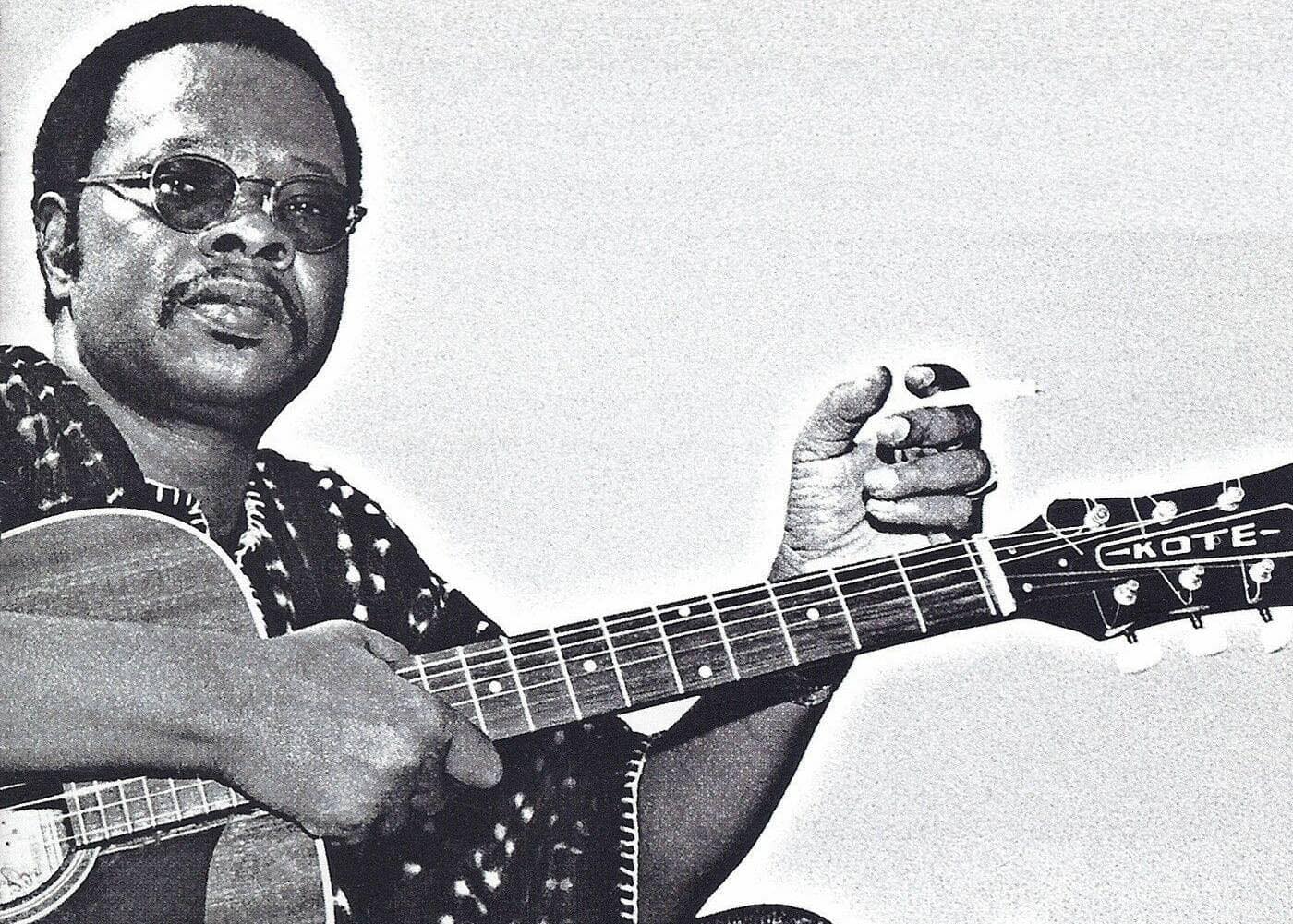

In 2003, after 34 years in the music world, he released ‘Koté,’ a 14-track album produced by Syllart Productions, Idrissa’s first real commercially released work. In 2010, he released another album, ‘Djitoumou,’ featuring the track ‘Bèrèbèrè’ with Ali Farka Touré, a song that became famous as part of the soundtrack to the film Black Panther.

“Everyday life inspires me”

It’s really fantastic to have you. How are you doing?

Idrissa Soumaoro: I’m very happy to answer your questions. I’m well, thank you.

Are you excited about the new album coming out via Mieruba? What led you to decide to write material based about Diré, a town where you met your wife. Is it like a spiritual healing to life’s struggle?

I’m very happy about the release of my album ‘Diré.’ Diré is a very important town for me. It was my first place of employment as a music teacher, the place where I met my wife and where our first child was born. I’ve also met some very nice people in this lovely town, which I miss so much.

When did you first move to Diré and what was life there like?

I arrived in Diré in October 1971 to teach music at the IPEG (Institut Pédagogique d’Enseignement Général), now the IFM (Institut de Formation des Maîtres). The town was beautiful and welcoming. But it seems that today, Diré is not the same as it was in the 70s.

Tell us how you usually approach songwriting?

Talking about my songs, without forcing the writing, I always wait for the inspiration that can come from a word, a sentence, a title, something said or done around me. Everyday life inspires me. I’m a satirical writer and humour is the spice of my satires. I also sing about love, nostalgia, respect, understanding, peace, et cetera.

How did the recording session go?

After the first recordings in the Manjul studio in Bamako-Mali, I was totally satisfied. The product was appreciable.

I would love to talk about some of the early days. You were fairly young when forming Djitoumou-Jazz de Ouéléssédougou.

My band, Djitoumou jazz 1965-66, had very little equipment: acoustic guitar, timbo, djembe, maracas and vocals. No amplification. We used to get the villagers dancing in a classroom every Saturday night. The group disappeared when I left for the INA in 1967.

Would you like to elaborate on the formation of ‘L’Eclipse De L’I.J.A.’?

L’éclipse de l’IJA was formed in 1978 with the aim of raising awareness for the emancipation of blind people in Mali. The orchestra’s songs were recorded in the Radio Mali studios in 1980-81, my second year at the INA. The technical resources were precarious, but the technician, Boubacar Traoré, was very competent. All of us – the UMAV (Union Malienne des Aveugles), Amadou, Mariam, the musicians and the students – were very proud of the results of our research, which I called ‘Le Tioko-Tioko’ (whatever it takes) to universalise our traditional music. The Idrissa Soumaoro / L’Eclipse De L’I.J.A. has been reproduced more than once around the world.

I would also appreciate it if you can share some words about Ambassadeurs Du Motel. How did you enjoy being part of it?

The Ambassadeurs orchestra was created by Ousmane Makalou in 1969 to liven up the bar at the Motel in Bamako, where he was manager. This group was a school, a fruitful passage for all its members from 1969 to 1978. Five years of hard work and joy, appreciated by us all. I’ve always loved helping others to the point of forgetting myself. I met Amadou Bagayoko in 1970 and we never left each other.

“Music is a privileged means of socialisation and emancipation”

What led you to take interest in problems that blind people experience? You went to Birmingham to study braille musicology…

Music is a privileged means of socialisation and emancipation for the people with visual disabilities, because music means hearing, touch and spirit. I studied Braille musicography at the Royal College and Academy of Music for the Visually Impaired in Hereford, England. I also passed degrees in theory, piano, guitar, flute, English Braille (full and abbreviated) and the first certificate at Cambridge University before taking a Masters in Special Education for the Visually Impaired at Birmingham University in 1986.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

I love all the ‘L’Eclipse De L’I.J.A. songs. Teaching theory and practice, raising awareness through music was my task at the IJA. I’m thinking of our concerts across the country. These were events that enabled us to show people that young blind people can write and read. Parents who thought that a blind child was just a curse for his family.

Is there any unreleased material you would like to see being released?

There’s nothing in the drawer except texts to be set to music as time goes by and inspiration strikes.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Nicolas Réméné

Idrissa Soumaoro Facebook

Mieruba Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube / SoundCloud