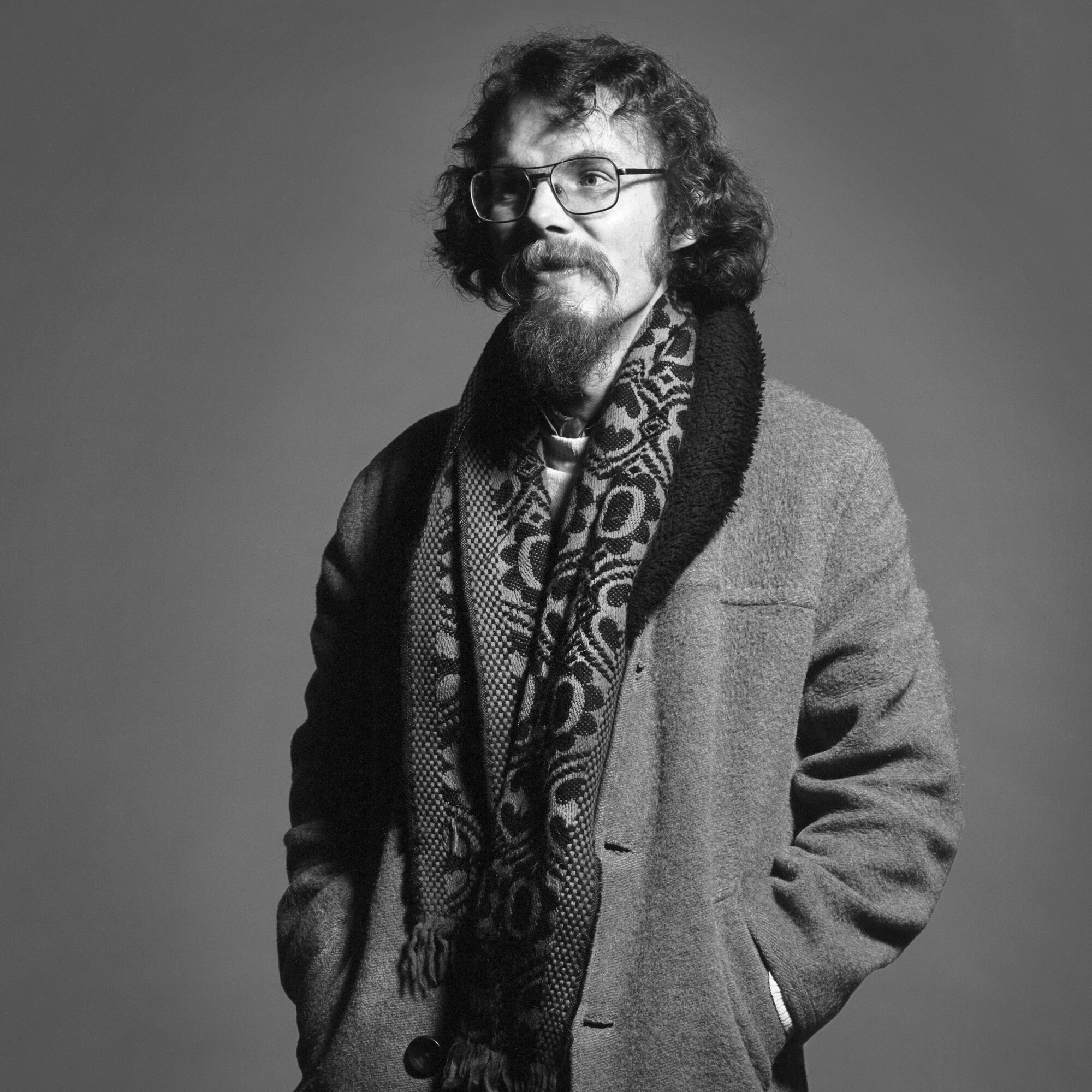

Guy Cabay | Interview | “Cabaycédaire”

Guy Cabay recorded two extraordinary albums more than 45 years ago that were recently compiled by Bertrand Burgalat’s Tricatel label under the name of ‘Cabaycédaire’.

Guy Cabay is Belgian jazz musician, composer, singer and multi-instrumentalist, born 1950 in Polleur. He is a unique personality on the Belgian scene.

“My passion for music comes from my family circle”

It’s really wonderful to have you. How have you been in these weird times? What currently occupies your life?

Guy Cabay: I’m a jazz musician, pianist, vibraphonist and composer. I studied musicology at the University of Liège. I taught at the Conservatoire Royal de Bruxelles and the Conservatoire de Musique de la Ville de Luxembourg until I reached retirement age in 2015. Since then, I’ve lived a peaceful retired life. My days were punctuated by walks in the Ardennes countryside and musical sessions. I never stopped writing or performing. I was quietly preparing a voice-piano show with visual projections entitled “Carrousel-Village”.

Then suddenly, the unexpected. Bertrand Burgalat and the Tricatel label contacted me. Bertrand had just discovered a somewhat forgotten facet of my creations. Forty-year-old records.

In 1978, at the request of a Belgian radio and television producer, I wrote a few songs in Liège Walloon: an astonishing marriage of my country’s dialect and original compositions inspired by Brazil. The result had its moment of glory at the time, but then fell back into oblivion. I might have had international success, but due to an unscrupulous producer, the record never made it beyond Belgium’s borders.

So it was a pleasant and fantastic surprise to learn that a French label was interested in my “historic” production.

Are you excited about the upcoming reissue of your two albums?

I’m obviously excited about the reissue of these old albums. And not just me! My Walloon language too. It’s finally going to get some of the recognition it deserves. That’s great.

Tell us about the material on those two albums? What do you recall from the recording session? What was your overall vision?

It all began in 1976. I was doing my military service (it was still compulsory at the time) when I was contacted by Françoise Lempereur, a fellow student at the University. She explained that the radio station was organizing a new dialect song contest and was looking to dust off the repertoire. “You speak Walloon and play jazz. Couldn’t you compose something a little more modern?” I complied and wrote two songs that were championed by a singer from Liège. Unfortunately, I was unsuccessful. The following year, my friend repeated her request. I wrote two new songs but found myself without a performer. Then, in a fit of recklessness, I had the audacity to sing myself: a big first. I’d never done it before in my life, and when you consider that there’s an abysmal distance between singing in the shower and performing in public, it’s easy to understand why I had the stage fright of my life. Nevertheless, I made it through to the televised final of the contest, and my collection of Walloon songs had been expanded by two new tracks.

How did you originally get interested in music? Can you tell us about your upbringing and love for jazz music?

That’s where Michel Dickenscheid, my saxophone-playing cousin, came in. We were like two brothers. We’d played together in dance bands. It was with him that I’d met Raoul Faisant, one of the glories of Belgian middle-jazz. I was about fifteen. I was listening to Eroll Garner, Ella Fitzgerald, Chet Baker or Stan Getz and Astrud Gilberto. All my friends (and even my teachers) thought I was a Martian. I wasn’t really into the Beatles or the Stones, and even less into French rock.

Michel, a brilliant sound engineer, had just set up a recording studio. Initially, he had set it up to record himself. One thing led to another, and he began recording other artists and had his own label, Les disques MD. Many Belgian musicians and singers of my generation produced their first opus with him. He made me a surprising proposal. I had four songs in the walloon in my pocket. Why not write a few more and produce an album? No sooner said than done. In 1977, I went into the studio and a 10-track LP was released the following October. It was entitled ‘Tot-a-fèt rote cou-d’ zeûr cou d’ zos’ and was an instant success. I was quickly dubbed the “most Brazilian of Liège.” I received proposals from a whole series of publishing houses, but unfortunately I signed with the wrong one. The album was never released abroad. That didn’t stop me from performing here and there outside Belgium, but it was always anecdotal.

How did you begin working with Michel Dickenscheid, who released your records in the 70s and 80s?

For the recording session, I could count on the help of musicians from two very different backgrounds. At the time, I was accompanying a Belgian singer by the name of Jean Vallée (runner-up in the 1978 Eurovision Song Contest), and my comrades agreed to take part. On the other hand, my friend Steve Houben – a formidable alto sax and flautist with whom I’d been playing jazz for years – had just returned from a stay at Boston’s Berklee School of Music, and he had two formidable American musicians in his suitcases: tenor sax player Greg Badolato and drummer Eddie Davidson. They gladly joined the team. And as backup singers, I asked my sister and one of her friends to join us.

That’s the whole story. The second album, ‘Li Tins, lès-ôtes èt on pô d’ mi,’ was recorded the following year with the help of my colleagues from the first jazz school we’d created in Belgium, the Séminaire de jazz du Conservatoire de Liège.

And, icing on the cake, once again with American musicians that Steve had just brought back from a second stay at Berklee. Among them was a guitarist who was to become a world star: Bill Frisell.

What are some records that you’re most proud of and why?

My passion for music comes from my family circle. Both my grandfathers were musicians, one a clarinettist who taught music theory to the young members of the village brass band, the other an organist. Nevertheless, I never knew them. They left us before I was born (medicine hadn’t yet made the progress it has today), but their aura remained with us for a long time. That’s where my passion for music came from, and the encouragement of my school teacher, who liked to say that I was one of the only ones in the band to sing in tune. Unfortunately, circumstances prevented me from attending a conservatory. So I studied music on my own. At the end of secondary school, I hesitated between a career as a scientist or an artistic future, opting for the latter and entering the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters at the University of Liège to study art history and musicology. I finished with a dissertation on fifteenth-century music and went on to prepare a doctorate on the subject. But jazz was already there. It was to become my royal road, and it was my first record in Walloon that would definitively determine the rest of my career. I left medieval music behind and embarked without regret on the paths of jazz and contemporary music.

It’s been awhile since your last album, are you working on something new?

The record I’m most proud of is my first. I’ve made many others (songs or instrumentals), but for myself, I’ve never found the same freshness of inspiration as on ‘Tot-a-fêt rote cou-d’ zeûr cou-d’ zos’. It’s like a first love.

“I’m currently working on a series of projects”

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

I’m currently working on a series of projects: pieces for solo vibraphone, new songs and my piano-voice show “Carrousel Village” – I sing and play while projecting the texts, their translation and photos on a big screen. And then there’s the project I’m currently finalizing. In 2007, I went to São Paulo in Brazil to record the rhythms for a new album in Walloon with some of Brazil’s finest musicians. The tapes have been waiting in my drawers for too long. Now I need to finalize them. Because the result is amazing. This time, my Walloon really sounds Brazilian.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

My last word is to thank Bertrand Burgalat and his wonderful team. Now it’s my turn to make the ‘Cabaycédaire’ shine.

And finally, a wish. I’ve read here and there that the lyrics of my songs sound a bit like an invented language. I love to make words sound good, and I sometimes spend an infinite amount of time finding the right syllable and the right place for the tonic accent to harmonize with the rhythm of the music. But the words I use are not insignificant. My songs tell real stories and deliver real messages. There’s poetry in my forgotten language.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Marcel Vanhulst

Tricatel Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / YouTube