The Five Year Plan | Interview | “We were very much C81 kids rather than C86”

The Bristol indie legends The Five Year Plan recorded a stunning set of tracks between 1984-1985, before C86 explosion, now available on Old Bad Habits Label and Breaking Down Recordings.

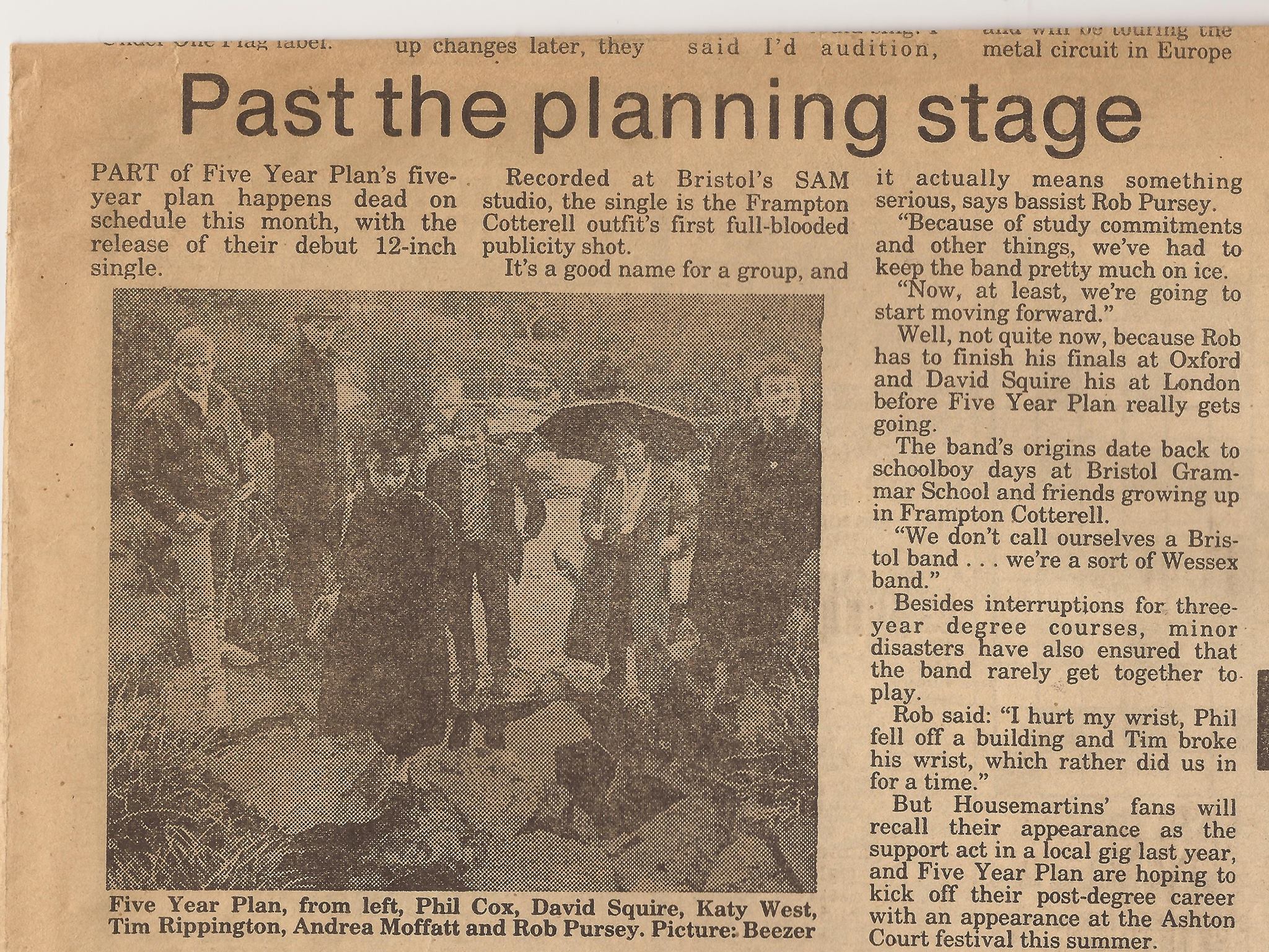

Tim Rippington and Rob Pursey were teenagers living in the Bristol backwater of Frampton Cotterell who got caught up in the excitement of the late 70s/early 80s independent music revolution. They taught themselves to play their instruments, recruited a few more like minded “musical outsiders” and, after a name change or two, formed The Five Year Plan. In less than a year the band had written and begun to perform enough songs to record an album. They became friends with Martin Whitehead, who was on the verge of creating Subway Records, also in Bristol. He lent them a 4-track on which they recorded some very rough demos, but Martin really liked them and wanted to do more. Convinced they were heading in the right direction, the band went into a proper studio to record the first two songs of what they hoped would be a fruitful relationship. But it wasn’t to be. The band themselves were utterly underwhelmed with the results and refused to play them to anyone else. They told Martin that, sadly, these recordings weren’t worth putting out. They would try again. But then… Time moved on, and so did Subway Records. The music The Five Year Plan was making didn’t quite fit with the new times. Some band members took up college places. Others were obliged to get jobs. They did manage to release two singles eventually, the second of which ‘Hit The Bottle’ was played by John Peel and got some great reviews in the National Press. But then the band split up and went their separate ways. The Five Year Plan’s debut album, all those songs written in a burst of enthusiasm and wonder back in the early part of the 1980s, never materialized. In 2022 Tim Rippington found himself listening to The Five Year Plan’s old demos and live recordings – and thought: this album really should have seen the light of day. These songs were good and they mattered deeply. He contacted Rob Pursey (bass), Dave Squire (keyboards) and Katy West (vocals) and proposed that the time had come to record them properly. All three agreed. Phil Cox, the original drummer, had moved to Spain, so his parts were faithfully reproduced by Bristol indie legend Rocker.

“It was like opening up an old diary and remembering the person you were thirty-eight years ago” is how Rob Pursey describes the recording process. “You change a lot over such a long period of time – but you also stay the same.” The passion to create emotive, ambitious, atmospheric pop music doesn’t go away. These old songs felt strangely familiar, like long lost friends.

The band made the decision to record the songs exactly as they would have played them in 1985. No additional frills, no editing of the lyrics. Just the way they might have sounded with a bit of cash and a decent production from someone who understood their music. The resulting album is a vivid picture of an indie scene in a provincial city where C86 hadn’t yet happened – where the band’s main influences were The Only Ones, The Go-Betweens, The Triffids, The Comsat Angels: all the groups who had started to chart a more ambitious, more intricate way out of the punk cul-de-sac.

“We were drawn together by a shared love of post-punk music”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Rob Pursey: I was brought up in a village called Frampton Cotterell. So were the other original Five Year Plan members Tim Rippington, Dave Squire and Phil Cox. The village was only ten miles from Bristol but we didn’t go there much – we couldn’t drive and you couldn’t get a late bus home. We would have been too young to get into gigs anyway. So Frampton was where we spent most of our spare time. We were drawn together by a shared love of post-punk music, usually accessed by listening to the John Peel show on Radio 1. We may have been the only people in the village who liked that kind of music, but we thought it was important: it felt like it was connecting us to a bigger, more troubled, less boring world. I remember buying the Blue Orchids album for a girlfriend for her 16th birthday. We played it on her parent’s stereo. Her Mum looked really uncomfortable as she listened. What was this horrible noise? Why was the singing so flat? I explained to her that the singer was out of tune with his environment, or something pretentious like that, which only disturbed her more. Why would anyone play music other than to be happy? I recount this only as an illustration of what life was like in a village in South Gloucestershire in the early 80s. Parents had nothing in common with their children in those days. They liked totally different things. We didn’t pay any attention to our parents’ music, and they, by and large, hated ours. I think we were quite lucky in this respect. We felt like we were doing something new. The boredom was good too: it motivated us to start a band.

Tim Rippington: I actually moved to Frampton in the last year of primary school (age 10), so I left all my friends behind and was quite isolated for a short time. Then I met Rob at the bus stop and it turned out that he and I were the only ones going to the same school from that village. We hit it off very quickly and we’ve been friends ever since. As young teenagers we were into a lot of things like trains and Scalextric cars, but going to a different school to everyone else (with different holidays) we also had quite a lot of free time to hang around in Frampton while it was practically empty of kids. I think this contributed to our isolation and finding a different perspective on life to many of our peers. Rob is right about our parents – I actually felt sorry for my son when he was getting into music because he’d play me something and I’d say “it just sounds like a poor man’s version of The Clash…” At least if he’d liked drum and bass or techno I could have said “call this music, it’s just noise?”… If you want to know what daily life in Frampton Cotterell was like, Rob’s song ‘Nothing Will Go Wrong’ on the first EP pretty much sums it up.

Was there a certain scene you were part of, maybe you had some favourite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

Rob: We started attending gigs in Bristol when we were a bit older – 16, 17. I don’t think we were part of a scene at the time: there weren’t all that many other bands in Bristol we felt we had much in common with. That’s true musically, but on a social level we were sharing venues (The Stonehouse, The Granary, Trinity Hall – and later, the Tropic Club) where lots of other bands were playing. Even if we didn’t sound like them, we hung around in the same places. Because we weren’t a Bristol band, but a bunch of oiks from a village nearby, we didn’t really connect with the trendy people in the cool pubs. We probably should have made more of an effort, but like a lot of bands, we were happy in our own little world. And people did come to see us. We were doing it on our own terms.

Tim: We weren’t part of any scene, but we did meet a few like-minded people on the music circuit. I remember a band called The Moral Minority that we became friends with, who played sort of grungy punk/Birthday Party sort of stuff. Like us, they were very isolated too. There was quite a big Bristol scene at the time with bands like Rip, Rig and Panic/the Pop Group, The Cortinas, the Electric Guitars, Vice Squad – but they were that bit older than us and we didn’t know them at all. We also met Martin Whitehead (Subway Records) around this time, via a mutual friend at school. He was just starting to write fanzines and he heard our first band and really liked it. Again, I think he was searching for an alternative to the mainstream in his own town.

If we would step into your teenage room, what kind of records, fanzines, posters et cetera would we find there?

Rob: You would find records by The Fall, Adam And The Ants, Pauline Murray And The Invisible Girls, Liliput, The Comsat Angels, Josef K. Those are the first names that come into my head. You’d also find some dub reggae. On the wall, you’d see the sleeves of those records. My bedroom was very small, so there wasn’t much on the wall. I remember me and Tim practising in there. I had to stick the neck of my bass out of the window, otherwise we were too cramped.

Tim: I got into a lot of music through my brother who worked on a local newspaper and got loads of free records. At first it was all metal/prog stuff like Black Sabbath and Uriah Heap which I didn’t really get, but then it turned into The Clash, The Ruts, The Damned, Jonathan Richman – these were the records that first got me really hooked. For some reason I did spend all my time at Rob’s bungalow, even though I had a much bigger bedroom in my house – it just felt more homely for some reason. There we started to listen to independent stuff – I remember reading the Indie Chart in the NME and thinking “who are these bands with really weird names?” Rob went out and bought ‘Where’s Captain Kirk’ by Spizzenergi just because we wanted to know what the hell it sounded like. Then it snowballed – the bands that Rob mentioned are just a fraction – there was the Scottish scene, with Postcard and Fast Records, there was Factory Records putting out Joy Division and A Certain Ratio, Leeds had the Gang of Four and The Au Pairs, then there were obscure foreign bands like The Names and Liliput. We loved all sorts, from The Mo-dettes and Helen McCookerybook to Killing Joke and The Dead Kennedys. But they all had one thing in common – they were all new bands, releasing stuff in the late 70s and early 80s. We absolutely took the “Year Zero” thing to heart – “No Elvis, Beatles or the Rolling Stones”.

By the time I was 17, I had quite a 7” collection and I had them all stuck up on my bedroom wall in plastic wallets. I thought that was the ultimate in cool. I must have had posters but I don’t remember – there were definitely no tennis players scratching their bottoms. When my mum was ill my dad bought her a radio cassette player which could record as well. After she passed away, I inherited that and I used it to record Peel sessions and then wake myself up in the morning with them. That’s how I heard the first New Order session and I remember being totally blown away by it.

Was The Five Year Plan your very first band or were you involved with any other bands?

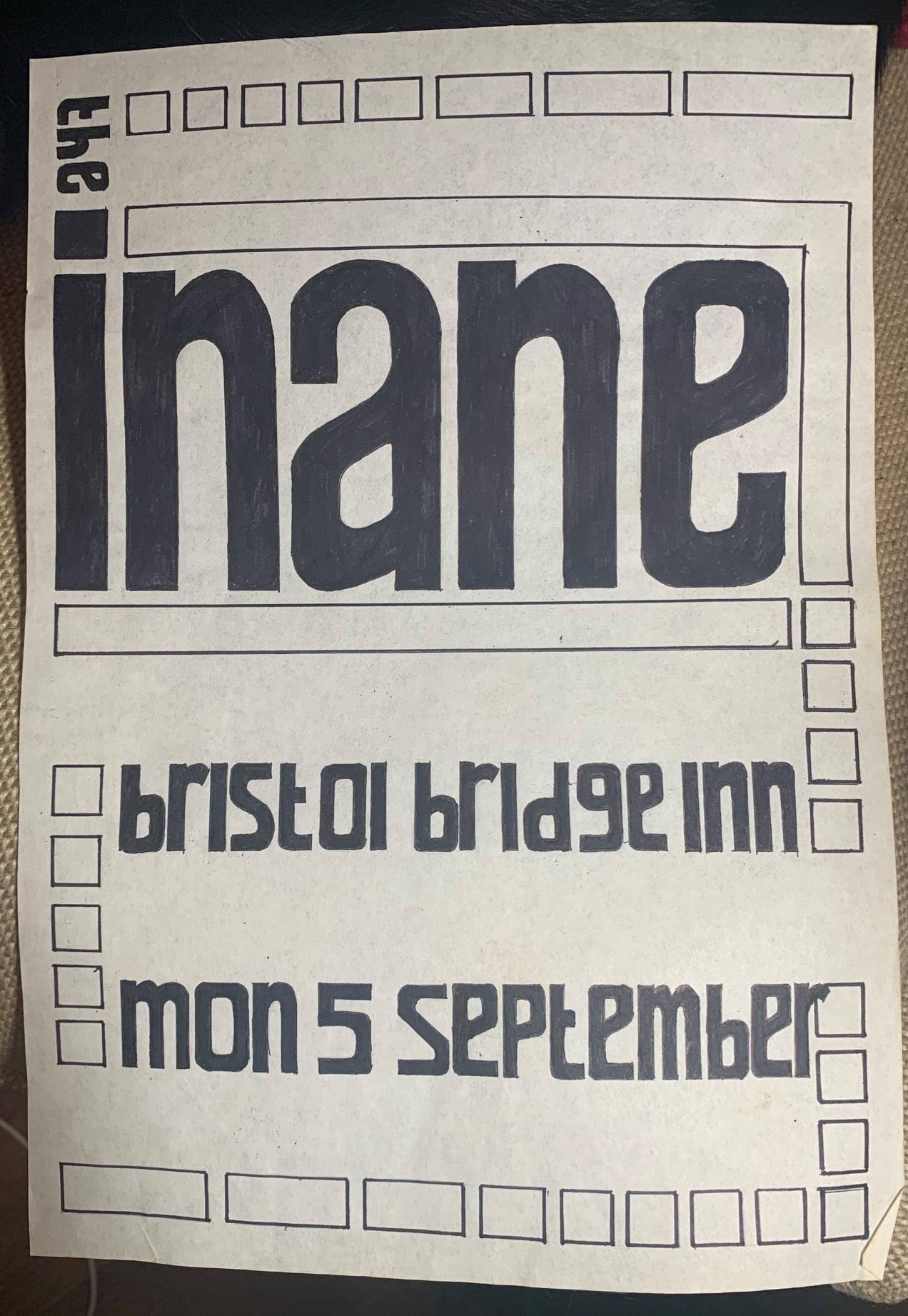

Rob: Our very first band was called The Inane. This consisted of the people who would go on to become The Five Year Plan. I think The Inane were actually quite good and, in some ways, more adventurous, if more limited, than The Five Year Plan. We were a three piece when we first started. Because Tim played rhythm guitar I played all sorts of melodies on the bass, far too many melodies: I don’t think I took my rhythm duties very seriously.

Tim: The Inane was our first ever musical project, and we were quite lucky that we got to record some of the songs in a proper 8-track studio, so they still survive. In fact, my girlfriend insists it’s the best stuff I’ve ever been involved with! As Rob says, we were quite adventurous musically, within our own little envelope. We had some doomy, morose songs inspired by The Cure and Joy Division, and some bouncy pop songs inspired by the likes of Orange Juice. It was a combination that was never really going to work, but we gave it a try! We played quite a few gigs as the Inane, starting in a local youth centre and then moving on to play venues in Bristol and even a couple of times away in Portsmouth and Cheltenham. Those were incredibly fun days when we absolutely believed that anything could happen and we could be huge musical stars. On one occasion a good friend of ours (who will remain nameless) telephoned the small venue where we were due to play to say he was from Polydor Records and he was coming along to the gig that night. We were so naïve we believed that someone from a major label might be coming to see us and we were absolutely petrified until our friend revealed the truth.

We eventually decided to end the band and start something new after we recorded a couple of songs on 16-track (‘Touched By Time’ was one) which sounded brilliant. We got offered a single deal with a label in Cornwall (via Martin Whitehead) and duly sent the tapes off, only to hear nothing further. After a few months of waiting we discovered that the guy running the label had had a nervous breakdown. This really shattered us, as we’d been hugely excited by the idea of doing a 7” single. I think that was when we sat down and decided we needed a fresh start.

Can you elaborate on the formation of The Five Year Plan?

Rob: Having done a few gigs and a couple of demos as The Inane, we wanted a new band to have more scope. We also wanted there to be females in the band – not just on vocals. Katy West was recruited as a singer and my next-door neighbour Andrea Moffatt was persuaded to play guitar. We probably started taking ourselves more seriously and started writing songs that were less eccentric.

Tim: By this time Rob was writing quite a few lead guitar lines so it was either a switch to guitar for him or recruit someone competent who could play the stuff he was writing. Andrea Moffatt was Rob’s next door neighbour, so recruiting her into the band was easy. She was technically a much better guitar player than me, so it worked out fine. Katy’s sister was a friend of Martin Whitehead, and so Martin knew Katy and knew that she had ambitions to sing. We tried her out by getting her to sing ‘Femme Fatale,’ a song we were familiar with through Helen McCookerybook’s band Skat – we didn’t know much about The Velvet Underground at this point I don’t think, we were still pretty much in Year Zero! She passed the audition, so then we were six. Katy didn’t really follow the kind of music we liked, but she was very keen, so it worked out ok.

“We were very much C81 kids rather than C86”

We are extremely excited that you finally released your old recordings. All the songs were recorded between 1984-1985, before the C86 explosion and before even Sarah Records existed. Would you like to share some further words about the songs and where did you record them? What was the initial plan; to get a label to release it or?

Rob: Most of these songs were written quite early in the life of The Five Year Plan. I can’t remember much about the process of recording them, but we were busy making demos and were hoping that a cool indie label would be persuaded to put them out, ideally having helped pay for a proper recording session. It was a strange time, as you say. A lot of the labels that we’d now see as important parts of the indie scene didn’t yet exist. We talked about releasing an album with Martin Whitehead, who was now about to start Subway Records, but we didn’t succeed in recording the songs properly, and abandoned the first studio efforts. And then Subway became a very different label, with the Shop Assistants and The Soup Dragons. It’s odd, but at the time this music seemed totally different to what we were trying to do. We didn’t use fuzz pedals, we didn’t much like The Ramones. Anyway, the momentum was lost – I went off to university, other band members got jobs and life moved on. But looking back, it was an incredibly exciting and productive time: the songs were good. I suspect that our ideas were greater than our musical ability. We were trying to do something that we were barely capable of pulling off.

Tim: A lot of people don’t realise that C86 was an attempt to replicate an earlier NME tape called C81 – and we were very much C81 kids rather than C86. As Rob says, all the songs on the LP were written early in the band’s lifetime, in a rush of excitement at having the new lineup and a chance to sound a bit different. We were able to come back and record them now because we recorded some very rough 4-track tapes within a couple of months of starting the band, and many of these songs date from that time. A few others were recorded live, so we have versions of all of them to look back on. Which is just as well, as none of us remembered them all that well!

We also included ‘Touched By Time’ by The Inane because it was a regular in the Five Year Plan’s live set and for a long time the only song we carried over from the Inane. I’m pretty sure we considered ourselves to be just like New Order, who were still refusing to play old Joy Division songs at that point!

Would love it if you could provide insight on the albums’ tracks?

Tim: I’ve recently been reading Stephen Morris’s autobiography, where he describes how Joy Division wrote their songs – essentially, they’d try to write a song that sounded like something they liked, but it would end up sounding like them instead. I think this is how most young bands operate, and it was certainly true of us.

‘Wiser Older But Wiser’ definitely started off inspired by the Comsat Angels, who were one of our favourite bands at the time, especially the LP ‘Sleep No More’. The drum pattern is definitely an attempt to mimic the Comsats, as are the guitar harmonics. But the song ends up sounding much lighter, partly due to Katy’s vocals but also because there is a pop element to our songs that we could never keep hidden. I wrote the song about a mutual friend of ours who was pining after a girl he couldn’t get together with.

‘Six Feet Under’ was definitely inspired by New Order, but again it has a bounciness to it that they would never have done in those early days. It has a touch of the Go-Betweens about it too, another of our favourite bands at that time. The two-string guitar part in the breakdown is definitely inspired by ‘Cattle and Cane’. The song was about my dad, who worked incredibly hard in his job for the Health Service, and kept a huge bottle of Paracetamol on his desk. I was very worried that this frantic lifestyle and commitment to work would lead to an early grave, so I wrote this song as a warning to him. Of course, he never heard it.

‘In Camera’ – More Go-Betweens influence here. The song was written whilst I was at University in Sheffield, and it’s about a girl I met at a party whilst severely under the influence. I found it very difficult to meet and talk to girls back then, I was very shy – unless I’d had a few drinks, when I usually turned into a complete moron. So this is about that really.

‘Tense’ –This is one of those songs that we wrote and then discarded very early on. Much of the song is held together by just bass and drums, which was quite brave and really not something that the groups who were signing to Subway were doing. The original demo is a duet, with Katy also singing the main verse, but we couldn’t make it work when we came to record it – Katy couldn’t remember the song at all! I remember this song always had the nickname “Tents” because that’s what certain members of the band thought I was singing about – probably why it got dropped so quickly!

‘Useless’ – My mother died of cancer when I was 17 – this was a song I wrote about the day she died. I went out for a long walk, I thought I’d have all these thoughts flying around in my head but actually there was nothing – I was completely numb. This song is supposed to sound like ‘Ceremony’ by New Order but again our pop sensibilities couldn’t be kept under wraps!

‘Peacetime Broadcast’ – (Rob) this was one of mine, unusually. Looking back, I seem to have been a bit idle when it came to writing lyrics. It might be because I’d given up on singing, and I really was more interested in the melodies – I mainly liked writing bass lines and lead guitar lines. Anyway, Peacetime Broadcast is an exception and the world can be grateful that Katy sang it, as her pure uninflected style really works, and hopefully prevents the song from sounding too pretentious. It’s all about an imagined day in the future when people are being conscripted for war against an ill-defined enemy by a totalitarian UK government. (I must have been a lot of fun to hang out with in 1985).

‘What Is To Be Done’ – Rob wrote the music for this one and I contributed the words. One of my favourite songs, it has lived in my head for the last 40 years. The title was stolen from a paper by Lenin, who I was studying in my spare time at University. I used to sit in the library and read these great thick tomes about the history of the Russian Revolution and biographies of people like Trotsky and Stalin. This was meant to be an anti-Thatcher political song, but despite all that reading all I could come up with was this!!

‘The Only One’ – A true lost gem from that first demo tape. No one but me could even remember us doing this song when I first touted it around to the rest of the band. Orchestral Manoeuvres meets New Order. We had two keyboards at this point, a Sequential Circuits Pro-One which was all knobs with strange words like ‘Pulse-Width’ and ‘LPO/Clock’ – we really struggled to get a decent sound out of it, but it made some really great noises whilst we were trying – and a tiny Casio keyboard which we had bought when Dave Squire first joined The Inane. Andrea Moffatt played second keyboard on this when we first learnt and recorded it – we did that on a few other songs too – it all added to the visual interest onstage, or so we thought. We used to use an ironing board as a keyboard stand too, something I think we picked up from the Higsons. We were still students, our money didn’t run to purchasing a proper keyboard stand.

‘Touched By Time’ – The only song we carried over from The Inane days at this point. I think when we first wrote and recorded this song we really thought we had made it. Its sister, a song called ‘Cares’ that we recorded at the same time, sounded really good too. The fact that these recordings came out so well probably contributed to us not finding a home on Subway records, because when we came to record our first songs as The Five Year Plan we just didn’t capture the same feeling or intensity. This was partly because our favourite engineer had left the studio, partly because I had left all my pedals at university and partly because we just didn’t get it right. We were really disappointed with the results and went off to sulk for a while – I don’t think we even let Martin hear them and make up his own mind. More songs about feelings and girls…

‘A Religion With Me’ – Another double keyboard song, this one was written by David. There’s a touch of Gang of Four about the guitar playing I think. Rob did a lot of high, melodic bass playing and the end of this song is a really good example.

‘Final Scene’ – When we came to record this song, I realised that I must have played the original demo version with a capo, because everything was in the wrong key! It took a bit of sorting out, but I’m glad we left it in this key as Katy’s singing sounds really nice in the lower range. This is a song about the word “love” and how it can ruin everything…

What led you to release the two singles for Breaking Down Records? How come the album recordings weren’t issued at the time?

Tim: We never had the backing of a record label, so recording an album was out of the question. If our first recordings had come out better, we might well have signed to Subway and recorded an album for them, but that wasn’t to be. There were no other indie labels in Bristol, and although we sent a few tapes off (to people like Factory!). We never really tried too hard to get signed. We thought the best way to gain some attention was to release a single on our own label, so after the first recordings failed, we wrote some new songs and tried again. Those recordings were better, although I don’t think any of us were really satisfied that we had got what we wanted from them. But with no money, we had to go with what we had. We went along to Revolver distribution, who were quite a big set up by now, one of the Cartel group of indie distributors, and they agreed to distribute the single for us. So that’s how we came to release ‘Nothing Will Go Wrong’ and ‘Brand New Car’ as a 12” single. We even got to master it at Abbey Road, where the technician was really impressed with the recording quality – I guess that’s the thing, a technically high quality recording does not always mean it sounds how you want it to. The third song on that EP was ‘Give Me A Lifetime,’ an instrumental version of which appeared on the very first 4-track demo. I remember Martin Whitehead saying he thought it sounded like Sade (if you remember her?).

After that quite a few things changed. We were discovering a lot of new music, both from the 60s (the Velvets, Bo Diddley) and more contemporary (people like Microdisney, The Only Ones, The Triffids, The Three Johns). We wrote and demoed some new songs which were a bit more poppy but with a different feel altogether. One of these was ‘Hit The Bottle,’ which we thought was a real humdinger of a song. The original demo sounded ok but we knew we could get a much better recording if we went in again with our original producer, a guy called Steve Street. Steve had left the studio but agreed to come back to produce us, and lo and behold we came out with something we were much happier with. ‘Hit The Bottle’ really had the sound we wanted, and the other side ‘Swallow Your Pride’ was magicked up out of thin air – I think we only wrote it the week before! Both songs sounded great and Revolver agreed again to distribute it. The single got played a couple of times on John Peel, which meant we’d made it in our eyes. But it never really sold many, and after that, things went a bit sideways. Our drummer Phil Cox broke his leg and was out of action for six months. Rob was off at Oxford and started to play with Talullah Gosh (although only for three gigs). I met Martin Whitehead in a pub at Christmas and persuaded him that The Flatmates needed a second guitarist for their upcoming tour with The Wedding Present. And that was pretty much the end of things, at least for the next year or so.

What influenced The Five Year Plan’s sound?

Tim: I think we’ve mentioned most of the things that influenced us, but I would say that production was also key. I loved the Martin Hannett production sound, and the sound of that second Comsats record. Dark, sparse, reverbed up. The opposite of a lot of what was to come from C86 really. If you listen to the difference in production between ‘Nothing Will Go Wrong’ and ‘Swallow Your Pride’ you can hear what I mean – one was very clean, no reverb, the other has a lot more ambience about it.

Rob: Josef K maybe influenced me more than any other band, but I did like the emotion and the melodrama of the Comsat Angels and of the gloomier Factory records.

What kind of places did you play? What are some of the bands you shared stages with?

We played mainly in Bristol, at clubs such as The Tropic Club which was the place to play for bands of our size. Really dark and sleazy. Upstairs was a Caribbean restaurant serving goat curry. This was the place where The Flatmates’ Rocker and Martin put on loads of bands in the mid-80s under the club name of The Bunker – people such as Primal Scream and Sonic Youth….

Our biggest gig was probably supporting the Housemartins on a boat called The Thekla in 1986 – this was around the time they released their first single ‘Flag Day’. The gig was packed and they were a great bunch of lads. We also supported Pauline Murray and the Jazz Butcher at the Tropic Club and The Flatmates at Bath University. Our only London gig was in Camden supporting the Groove Farm, with whom we briefly shared a manager and a rehearsal room.

When did you stop playing together and what occupied your life later on? Tell us about the bands that followed.

Tim: After ‘Hit The Bottle’ we recorded a few more demos and then had more than a year out doing various things whilst Phil Cox’s leg healed, as I’ve mentioned above. It felt like there was unfinished business though, so in 1989 we got back together again to record a few more songs. These included ‘See You in Heaven’ which appeared on the first ‘Airspace!’ compilation, a charity record put together by Rupert from the Groove Farm and his friend Sara Tacchi, who was their roadie at the time. Dave Squire and I also recorded a song with Choo Choo Train which came out on the second ‘Airspace!’ LP. This was done at the end of their tour with the Flatmates in 1988 (just after I left the band because of a falling out with Martin). Our last ever Five Year Plan gig was in Birmingham in 1989 supporting the Groove Farm, who had always helped us out quite a bit (and vice versa).

After that, I spent some time driving the Groove Farm around and being a guitar roadie, including on their gigs with the Wedding Present. In 1990 I went to Australia for six months, then came back and opened a recording studio. By this time The Groove Farm had split and some of them had formed the Beatnik Filmstars. I began recording them in my studio and eventually joined the band, making about four or five LPs and touring a lot in Europe and once in the USA, supporting the Flaming Lips on a month-long tour. I had kids and eventually it got too much to be in a touring band so I gave it up, something I almost immediately regretted, but in time I started recording and making music again under the name Forest Giants. We recorded four LPs and did a session for Radio 6, before that eventually fell apart. There was a second spell with the reformed Beatnik Filmstars, then a few dodgy records as The Short Stories with my friend (and FYP archivist) Steve Miles. The recordings always felt more like demos in that band and I have a desire to re-record some of them someday, as I think there’s a bit of a treasure chest in there if it is done properly. Then in about 2013 I got together with The Charlie Tipper Experiment and I’ve been playing with them ever since – we’ve been through a few name changes and are currently known as The Charlie Tipper Rebellion. We’re all really good friends in that band so we do it for fun as much as anything else, but the records are good – we have a new LP coming out in 2024 on Old Bad Habits called ‘Second Time Around’. Something we all wonder about from time to time, the chance to have another go and do things differently?

Rob: I met up with Amelia, Mathew and Pete and became part of Talulah Gosh, but could only stick it for three gigs. Maybe I was missing the melodramatic gloominess of pre-C86 music, maybe I didn’t like the way the hype was already bigger than the band. The songs in Talulah Gosh were genuinely excellent and they have stood the test of time, but the band quickly became about something other than the music, and it didn’t last very long. Anyway, I hooked up with the same people a year and half later and Heavenly started. I loved being in that band. None of us could care less about the press or what anyone thought, and just went for it – and luckily became part of a scene that was totally autonomous and surprisingly big. A lot of people came to our gigs; we went to America and Japan. I finally got to meet John Peel. The band came to a terrible abrupt halt when Mathew took his own life. Still in a state of shock, we re-assembled as Marine Research, but it didn’t endure. Since then, me and Amelia have had a series of bands, changing the name at regular intervals in a way that is guaranteed to make success unlikely – not that we wanted it much. We had jobs and kids. And now, in 2024, we are still doing it, sometimes as Swansea Sound, sometimes as The Catenary Wires. Oddly, these two bands have probably had more radio play than any other band I’ve been in. On top of this, we seem to be doing occasional gigs as Heavenly, which are great fun, but probably only if they happen rarely. I still love the indie music scene – the genuinely independent indie music scene – and we have started a label called Skep Wax so we can release our own stuff and other people’s.

Tim: David went off to become a school teacher and moved to America, where he learned how to play the 4-string guitar and got heavily into alternative country music. He recorded some stuff in Nashville with some of his musical heroes before eventually having to return back to the UK. Katy hasn’t done anything in music since we split as far as I am aware, she’s filled her life with other, more normal stuff. Phil Cox now lives in Spain but still plays drums in a band over there, which is nice as I think he’s one of the most talented drummers I’ve ever come across.

Tell us about the instruments, gear, effects et cetera you had in the band.

Tim: Our equipment really was pretty basic – whatever we could lay our hands on. I’ve described the keyboards above. My guitar was semi-acoustic for a lot of the time, but not a famous make. A Westone I think. I also had a cheap copy of a Gibson at some point, a white one like Mick Jones used to use in The Clash. Eventually I bought a Fender telecaster when I resigned from my job in the NHS and cashed in my pension!

Rob: My first bass was a very cheap Kay Fender copy. It weighed a ton and wasn’t great, but it did the job, although it probably stunted my growth. Later on, I saved enough to get a Westone Thunder 1A, which was a lovely bass and good for playing chords and nippy melodies. It got nicked, years later, after a Heavenly gig and I still miss it.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

I think that the Housemartins gig was pretty memorable, as was meeting Pauline Murray who was a real hero of ours at the time. Individual moments are a complete blur though, it’s very hard to remember back that far. In terms of songs, the ones I really like the most are the two on the last single – when we finally got to sound how we wanted. I’m now also pretty proud of our new LP, I think it’s shown that our belief in the music wasn’t completely unwarranted – I’d really love to know what people would have made of it if they had heard it back in the 1980s. But that’s something we’ll never know…

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Tim: Thanks for asking us, it’s been a pleasure. The last 18 months have been a lot of fun, recording the songs, meeting up again with Katy and David – I’ve kept in touch with Rob through the Catenary Wires and now Swansea Sound, but seen far less of the other two guys. Our recent gigs were a lot of fun too – we may be a lot older but I think we’re a bit wiser too and it showed

Rob: Yes, thanks very much for asking such good questions. Eighteen-year-old me is really gratified and moved that people are interested in the songs we composed back then. I’m really glad that we started The Five Year Plan and worked out how to be in a band. My life would have been a lot more boring if it hadn’t happened.

Klemen Breznikar

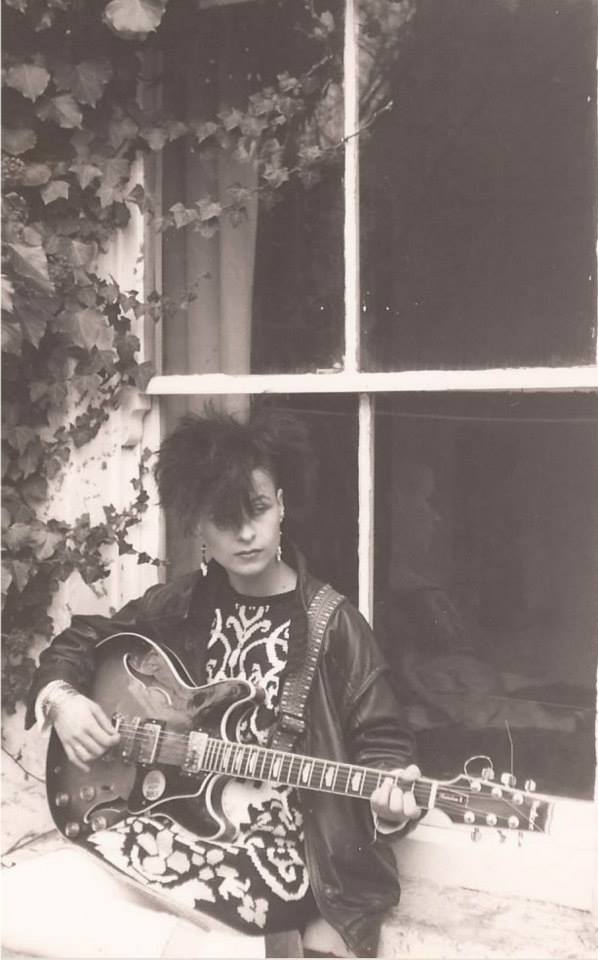

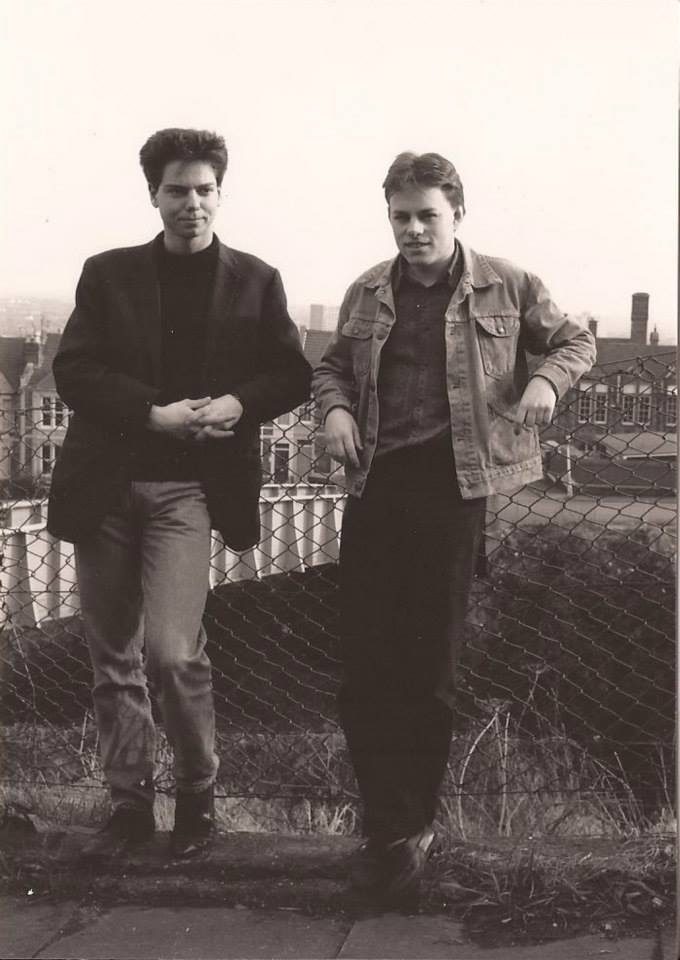

Headline photo: The Five Year Plan photo shoot for Venue Magazine

The Five Year Plan Facebook / Bandcamp

Old Bad Habits Label Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp

Breaking Down Recordings Facebook