From Sudden Death to Hammerhead: The Musical Journey of John Binkley

John Binkley is a bassist who began his musical journey with the remarkable underground group Sudden Death, later gaining broader experience with Sky Fire, and ultimately playing significant shows with Hammerhead, a band that had a devoted following and played at top-notch venues.

Hammerhead was a powerhouse in the 1970s Los Angeles music scene, captivating audiences with high-energy performances and solid musicianship. The band’s rise from local gigs to opening for major acts highlighted their talent and tenacity. Despite lineup changes and industry obstacles, they left a lasting impact on their fans and peers. This article delves into the history and evolution of Hammerhead, exploring key moments, memorable shows, and the enduring legacy they created.

Binkley attributes much of his success to luck, particularly his connections with notable musicians and his unique opportunities within the competitive music industry. His most memorable moments include playing in Hollywood, opening for well-known bands, and dealing with unexpected challenges, such as breaking his Gibson on stage. Despite the hurdles, his career has been filled with remarkable experiences and collaborations with future rock icons.

“Hammerhead became the hardest working band I was ever in”

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence or inspire you to play music?

John Binkley: I’ve discussed my background in earlier interviews for Sudden Death and Sky Fire. What I’ll add here is a memory from my childhood. My father worked as a resident radiologist at Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital in the late 1940s. One of the perks of that job was that hospital residents rotated assignments as on-set doctors at local movie studios. During those assignments, Dad met numerous movie stars of the day, including Jimmy Stewart, June Allyson, Fred MacMurray, and Jimmy Durante, among others. Jerry Adler was a virtuoso harmonica player, as was his brother, Larry. While Larry toured the world as a concert performer, Jerry found steady employment recording harmonica soundtracks for motion pictures and television shows, providing harmonica tracks for actors who appeared to be playing on camera. Dad and Jerry met on the Paramount lot and became fast friends. In fact, at Dad’s memorial service, Jerry Adler said that Dad “…was the best friend I ever had.”

Although Dad was already an amateur harmonicist, Jerry helped refine his talent and taught him to play a chromatic harmonica. Jerry would occasionally visit our home, and the two would have fun in our living room, playing harmonica duets to popular songs. I was young, but my memory of Jerry was that he was a fun-loving, energetic extrovert, and it seemed like the music had something to do with that. So not only was music a part of my upbringing, but I also had early exposure to a true professional musician, experiencing not only his love of music but also his ability to positively influence those around him.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

Again, this is ground I’ve covered in previous interviews for Sudden Death and Sky Fire, so I won’t rehash the details here. The short version is that I played piano from the time I was 6, transitioned to trombone in junior high and high school bands and orchestras, and then began to teach myself bass by ear when The Beatles, the British Invasion, and hard rock took over the music world in the late ’60s.

What bands were you a member of prior to the formation of Hammerhead?

My path to Hammerhead began in 1970 with Sudden Death, from its inception until singer Greg Magie, drummer Charlie Brown, and I formed Sky Fire in 1973. I stayed in Sky Fire for a year before joining Hammerhead. I’ve been interviewed about those bands and won’t go into details about them here. There was actually a month or two when I was in both Sky Fire and Hammerhead, doing gigs with each on alternating weekends, until I formally left Sky Fire.

Can you elaborate on the formation of Hammerhead?

Terry Brent, Hammerhead’s drummer, had been instrumental in bringing Sudden Death to Kim Fowley’s attention in 1971. Terry kept an eye on me from then on. He formed a cover band, Indian Summer, about the same time Sky Fire was born, and I went to see them whenever I had the opportunity because they were playing good songs and working steadily in clubs under Terry’s management. After a year, Terry began talking to me about a new band he wanted to put together. He had a guitar player, Woody Woods, who was a neighbor of his in Santa Monica, a second guitar player, Austin Addison, who had come to LA from Arizona, and a singer, Greg Sanford. All he needed was a bassist.

I was a bit reluctant to leave Sky Fire, but I was getting kind of burnt out trying to keep the band playing. Most of Sky Fire’s gigs were coming through my efforts, and I was beginning to see that I just didn’t want to be the one responsible for booking and managing the band. I had been unemployed since Sky Fire made its trip to Oregon in July, and I was hoping to support myself as a musician, but Sky Fire wasn’t working often enough to make ends meet.

I think Terry saw that as an opportunity. He engineered a pretty cool situation for me, if not for Sky Fire. Terry had been booking Indian Summer at a club in the Venice Beach area called The Attic on a regular basis. He made me an offer to book Sky Fire into the same club as Hammerhead, on alternating weekends, if I would sit in with Hammerhead while they looked for a bassist. That meant I’d be playing every weekend for a while, and as a bonus, I wouldn’t need to move my equipment out of the club! So I agreed.

As I recall, those were the last gigs Sky Fire played. Within a month or so, Sky Fire dissolved, and I found myself in Hammerhead full-time.

How did you initially meet Kim Fowley?

John: My contact with Kim began four years earlier with Sudden Death. It continued, although at a lower level of involvement, during Sky Fire. But Kim’s interest in Hammerhead grew markedly. Our drummer, Terry, was a common thread through it all, and now that Terry had a promising project under way, I think he began to press for Kim’s involvement. Terry was an aggressive promoter of the band to clubs and industry folks, and he believed in the band’s potential. So Kim came on board fairly early and, as in the past, wanted to hear an original song or help write one. We eventually went down the path of collaborating with him on a song that became ‘Summer Nites’.

“We were an exciting, energetic band in the same general way that Sudden Death had been”

Have you ever heard about a band called Hollywood Stars? The Hollywood Stars formed thanks to Kim Fowley, who had this idea of combining 60s pop with the attitude of hard rock. Fowley described his concept as a West Coast version of New York Dolls, and he set out to find musicians who would fit the bill. After the project was born, I guess something similar was with Hammerhead?

I definitely was aware of the Hollywood Stars, but not intimately. Kim was doing what Kim did: looking for existing bands, or creating ones, that he felt he could promote to record companies and cash in on publishing royalties for their music, especially if they had a gimmick. He was always looking for something that would make a band stand out, an angle. That’s how The Runaways came into existence, and other projects that he pushed.

Hammerhead wasn’t put together by Kim, and we didn’t have a trademark gimmick in our presentation, but we were an exciting, energetic band in the same general way that Sudden Death had been. We were very much in the public eye, and we were willing to collaborate with him on originals. That was enough for him to see us as a priority in his promotional efforts with record companies.

Terry Brent then recruited three members from Sky Fire: John Binkley, Greg Sanford, Charlie Brown? How did he find you, Woody Woods, and Greg Sanford?

Not exactly. I was the only member of Sky Fire to join Hammerhead. But it is true that Terry “recruited” me.

As I mentioned before, Terry and Indian Summer existed while I was in Sky Fire. They had a terrific female lead singer and very talented instrumentalists. Terry was booking them into all the right places, and whenever I could, I’d go see them play. At the same time, I was booking Sky Fire in as many venues as I could, but we were still having trouble playing steadily.

After about a year, both bands had discovered a club in the Venice Beach area called The Attic. Terry had some pull with the owner, and so the club booked Sky Fire. Then Terry quit Indian Summer and put together a new band along with Austin, Woody, and Greg, but they needed a bass player. So Terry talked me into filling in with them when I was available, and he booked this new band, Hammerhead, into The Attic on alternating weekends. He got me to book Sky Fire at The Attic on his off-weekends, so for about six weeks I played bass at The Attic every single weekend. I played stage left in both bands, so I just left my equipment set up in the venue and showed up to play with whichever band was booked. People started calling me the house bass player.

Anyway, Sky Fire was at the end of its life cycle by that point, and when it broke up, I just continued in Hammerhead full-time, without having to look for, or create, a new band.

As for Woody, all I know about his path to the band was that he was a beachfront neighbor of Terry’s and had a blues-oriented musical background from the South. I know less about Greg. I thought he was local until his brother showed up from Denver with his own band, so I guess those were Greg’s roots. Terry either found Greg through his work with Indian Summer, or through Musicians Contact Service. As the last musician to join Hammerhead, I missed out on the whole process of assembling the band.

Tell us about some of the early gigs you played?

Hammerhead started out at The Attic. It occupied the second floor of a two-story building on Lincoln Blvd. near Venice Beach, above a business that made sails for boats, and could hold maybe 400 people. Hammerhead immediately began to build a following at the club.

Not long after we started playing there regularly, we rebuilt the stage, converting it from a triangular shape in a corner at one end of the club, with short extensions of the stage along both walls, to one that was eight feet deep and ran the full width of the club. The change gave the club the feel of a real rock venue.

Using The Attic as a base of operations, Terry proceeded to book us around the Los Angeles area, always aiming for venues that would draw attention to the band. Pier 5 was such a venue in the San Fernando Valley, but there were others in that area of Los Angeles that we played. The FM Station (owned by Filthy McNasty) was one of those.

Hammerhead became the hardest working band I was ever in. In a matter of months, Terry had us playing every weekend and booked three months in advance. Coupling that with our rehearsal schedule, which was every day we weren’t booked except for the first day following a gig, it was total saturation. Generally speaking, we had gigs every Friday and Saturday, sometimes on Thursday, and occasionally also on a Wednesday or Sunday. It was relentless and just what I had been hoping for—I was working almost full-time as a musician.

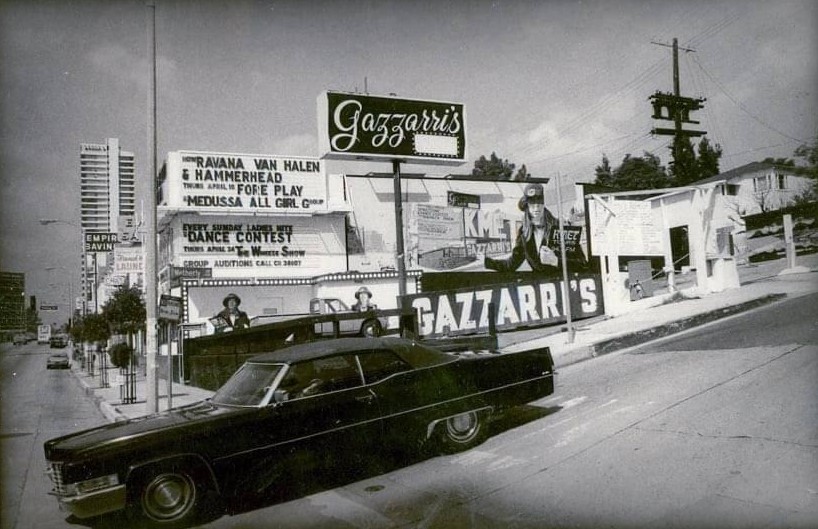

We played at a small club in West Los Angeles, near UCLA, called Ledbetter’s. We played in Pasadena at The Handlebar Saloon (more on that later). Eventually, Terry evolved into a rotation between The Attic, Pier 5, and Ledbetter’s. As if that didn’t fill our schedule enough, he quickly added Gazzarri’s, the legendary club on the Sunset Strip, to the mix. We were playing every weekend and booked months ahead.

Even gigs at The Attic would become memorable. At one point, Terry had turned the management of Hammerhead over to Rich Fazekas, who at the time was the road manager for ELO. He brought a couple of ELO members to one of our gigs, and the comment I remember from talking with them was that they liked our version of ‘Do Ya’ more than their own. Bonus: we got backstage passes to their show.

We worked our way up the ladder of Los Angeles club venues and eventually played the Starwood, which rivaled the Whisky as a showcase venue for the Hollywood scene. The Starwood had two stages: one originally showcased progressive rock bands (a la Genesis), then became a disco, and the other was set up for rock. Performers reached the stage by a stairway that descended along the wall at the back of the stage, coming down from the upstairs level where there was a bar and the green rooms for bands. Downstairs, the stage itself was four feet off the floor, large, and flanked by a PA system that was run from a sound booth at the rear of the club. A dance floor in front of the stage was ringed by tables and another bar. Pretty nice setup.

Being in Hammerhead also led to side gigs. Kim Fowley arranged for me to be the bass player for an all-star fundraising event at the Starwood. At one point, I was on stage with Mars Bonfire and Sky Saxon, performing ‘Born to Be Wild’ and ‘Pushin’ Too Hard’. During one of those songs, they had me do an extended bass solo—one of the best moments I’ve had. But the punchline to this story came a couple of weeks later when I stopped in at the Guitar Center to pick up some gear. I knew everyone there, and I had barely walked in the store when they asked me if I had played at the Starwood recently. Frank Zappa, they told me, had just placed a huge order for Gallien-Krueger equipment after hearing it at the Starwood. I jokingly suggested that I should get a commission on the sale, but they declined.

How much of your own material did you have? What did your repertoire consist of?

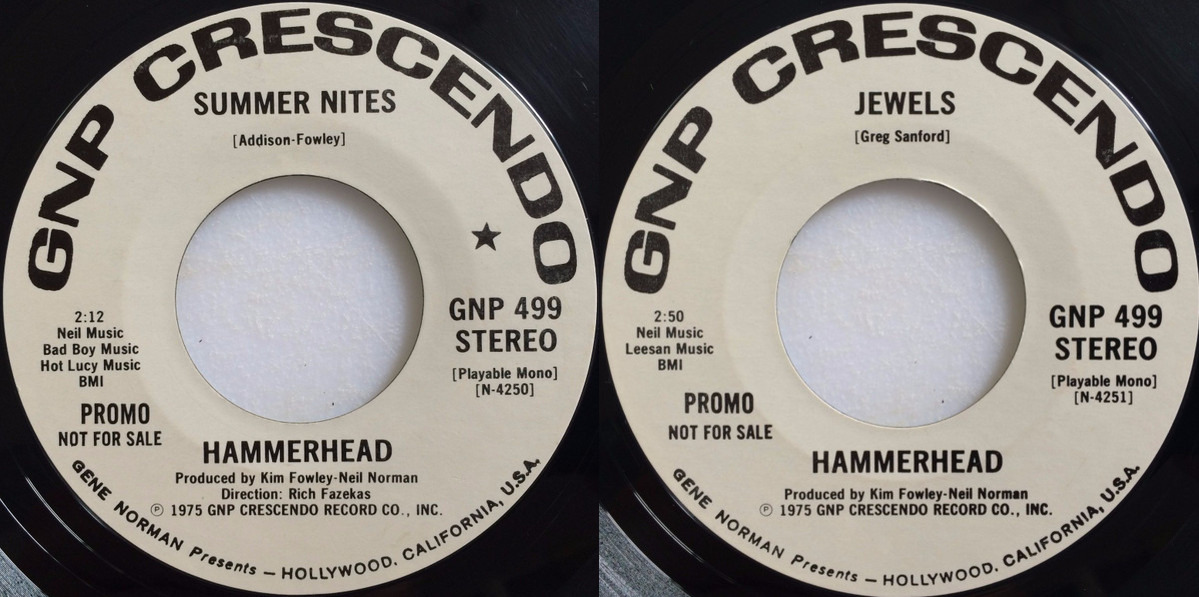

I can remember the band having three originals that we played regularly. Two of them were written by our singer, Greg Sanford: ‘Jewels’ and ‘Diamond in the Rough’. The other was ‘Summer Nites’. I think we had maybe one or two other originals, but I don’t remember the songs or their titles.

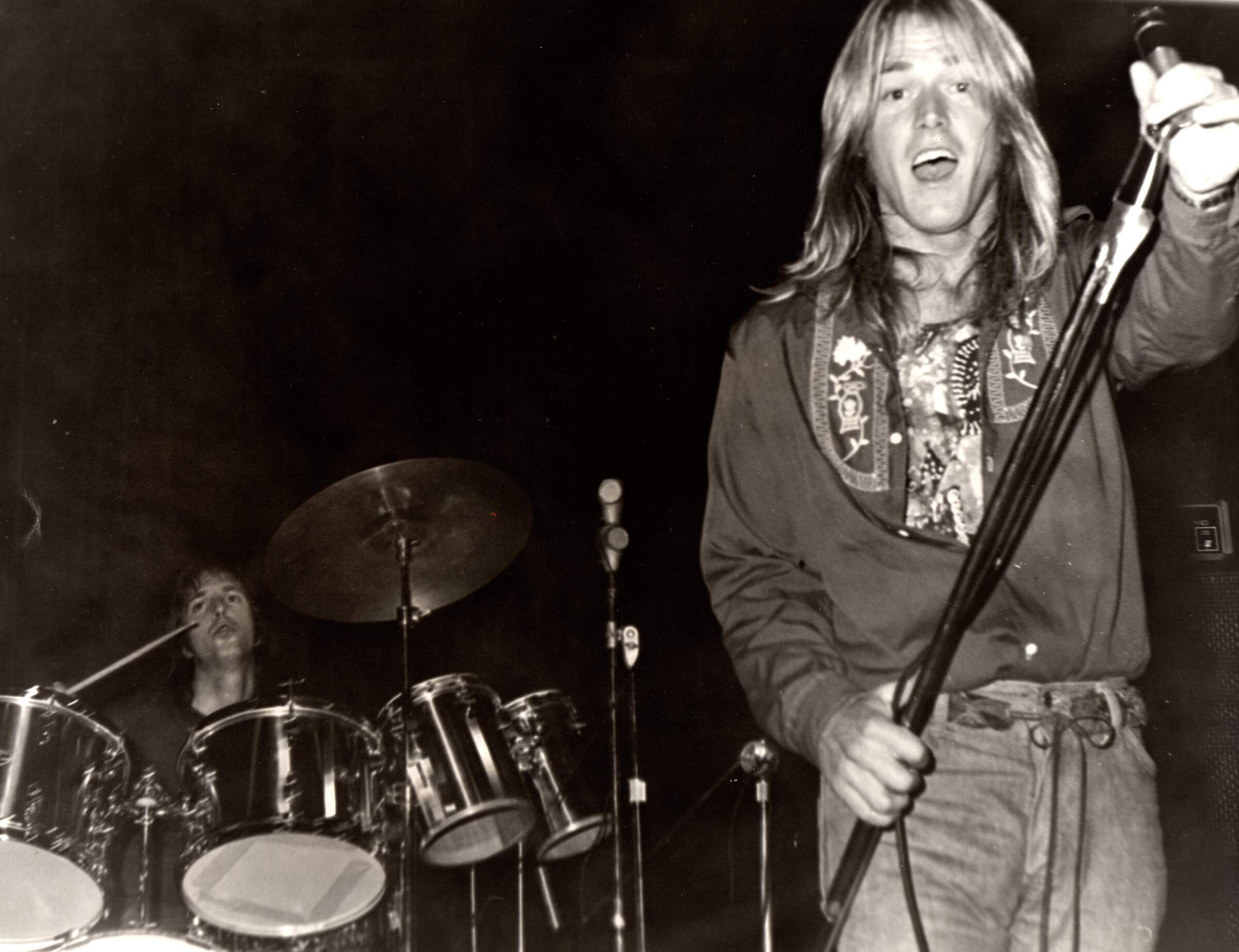

The rest of our repertoire was decidedly hard rock, drawn for the most part from recently released material, all of which fell right into the pocket of our guitarist, Austin. He could handle anything, and had an on-stage persona that removed any doubt about the band being a serious experience. Coupled with Greg Sanford’s dazzling presence as a frontman and the power rhythm section that Terry and I commanded, we could pull off just about anything we wanted.

Our big set closers were showcase songs: Grand Funk’s ‘Inside Looking Out,’ The Who’s ‘Pinball Wizard,’ and John Entwistle’s ‘My Wife’. Austin would usually set his guitar on fire with lighter fluid as part of a solo at an appropriate moment at each gig.

The core of our repertoire, if memory serves, included:

Led Zeppelin (‘Immigrant Song,’ ‘Out on the Tiles,’ ‘Night Flight,’ ‘Custard Pie’);

Jimi Hendrix (‘Red House,’ probably the only “slow blues” we did, usually early in the last set);

Deep Purple (‘Maybe I’m a Leo,’ ‘Smoke on the Water’);

Robin Trower (‘Day of the Eagle,’ ‘Fool in Me’);

Chicago (‘Southern California Purples’);

David Bowie (‘Cracked Actor,’ ‘Suffragette City’);

Ohio Players (‘Fire’ [a medley with Hendrix’s ‘Fire’ but at the Ohio Players’ tempo]);

James Gang (‘Funk No. 49’);

Ted Nugent (‘Cat Scratch Fever’);

Steely Dan (‘My Old School’);

Rolling Stones (‘Let It Bleed’);

Electric Light Orchestra (‘Do Ya’);

Elton John (‘Saturday Night’s All Right’);

Johnny Winter (‘Rock and Roll Hootchie Koo’);

BTO (‘Takin’ Care of Business’);

Bad Company (‘Can’t Get Enough’).

Bear in mind that we were not playing time-worn classic rock songs. Most of the songs we were playing were charting in real time. Every week or two, it seemed like there was a new album with at least one great song on it, and we would learn it. I bought up to 12 albums a week and brought songs to the band, which put us on stage playing the cream of high-energy, serious dance music at a level of delivery that put us in the top five club bands on the LA scene. One of the other four bands was the not-yet-signed Van Halen, so we were in good company.

I’m amazed that bands today are still playing those songs half a century later. My question is: WHY? Why ignore an enormous catalog of great music that has been released in the last 20 years or so by bands like Metallica, Megadeth, Bad Religion, Offspring, Stone Temple Pilots, Green Day, Anthrax, Dave Matthews, Matchbox 20, Cranberries, Alice in Chains, Avenged Sevenfold, Creed, Hoobastank, and their contemporaries? I’ve been a Bad Religion fan since I found them in 1995, but no one plays any of their music. Amazing. To me, Megadeth, Pearl Jam, Creed, Tool, Linkin Park, Nirvana, No Doubt, Avenged Sevenfold, Volbeat, and others are today’s classic rock. The traditional classic rock audience in clubs knows these bands and their music, and they are going to their concerts, so why not give it to them? I’ve never seen the point of running away from the core job we have as artists, which is to move the audience forward. Hammerhead did that by playing contemporary hits from a variety of genres with an energy level that approached an in-concert performance. Too few of today’s club bands are following in those footsteps.

What are some bands you shared stages with?

Well, easily the top of that list is Van Halen. At the time, Van Halen was unsigned—just a top-notch cover band breaking into the same Los Angeles club scene that we were. Probably a third of our gigs at Gazzarri’s were with them, as Bill Gazzarri had standing-room-only crowds whenever either of us played, and when we were booked together, a blocks-long line would snake along Sunset Blvd. There was friendly competition between us to see who would headline over the other and get the best of the two downstairs stages. Bill didn’t think it made much difference who got top billing, so he decided that whichever band came and set up first would get the top spot. I was living in Hollywood and working just a few miles away from the club, so I’d load up my stack and go to the club in the late morning, when the janitors and office folk would arrive, and set up my gear on the good stage. Bill would then put up the marquee with Hammerhead headlining. I should note that Bill listed bands top to bottom in the order they would be playing in the rotation. Bands went through the rotation three times, with the headlining band always being the third to play in each rotation.

There was one night when Van Halen was following us in the rotation. At the conclusion of our set, Van Halen was on their stage, ready to go; there were no breaks between bands. Greg looked over at them and said something over his mic like, “Ok, guys, we got ’em hot for you,” to which David Lee Roth replied over his, “Yeah, you got ’em hot, but we’re gonna make ’em come!” Those were great gigs.

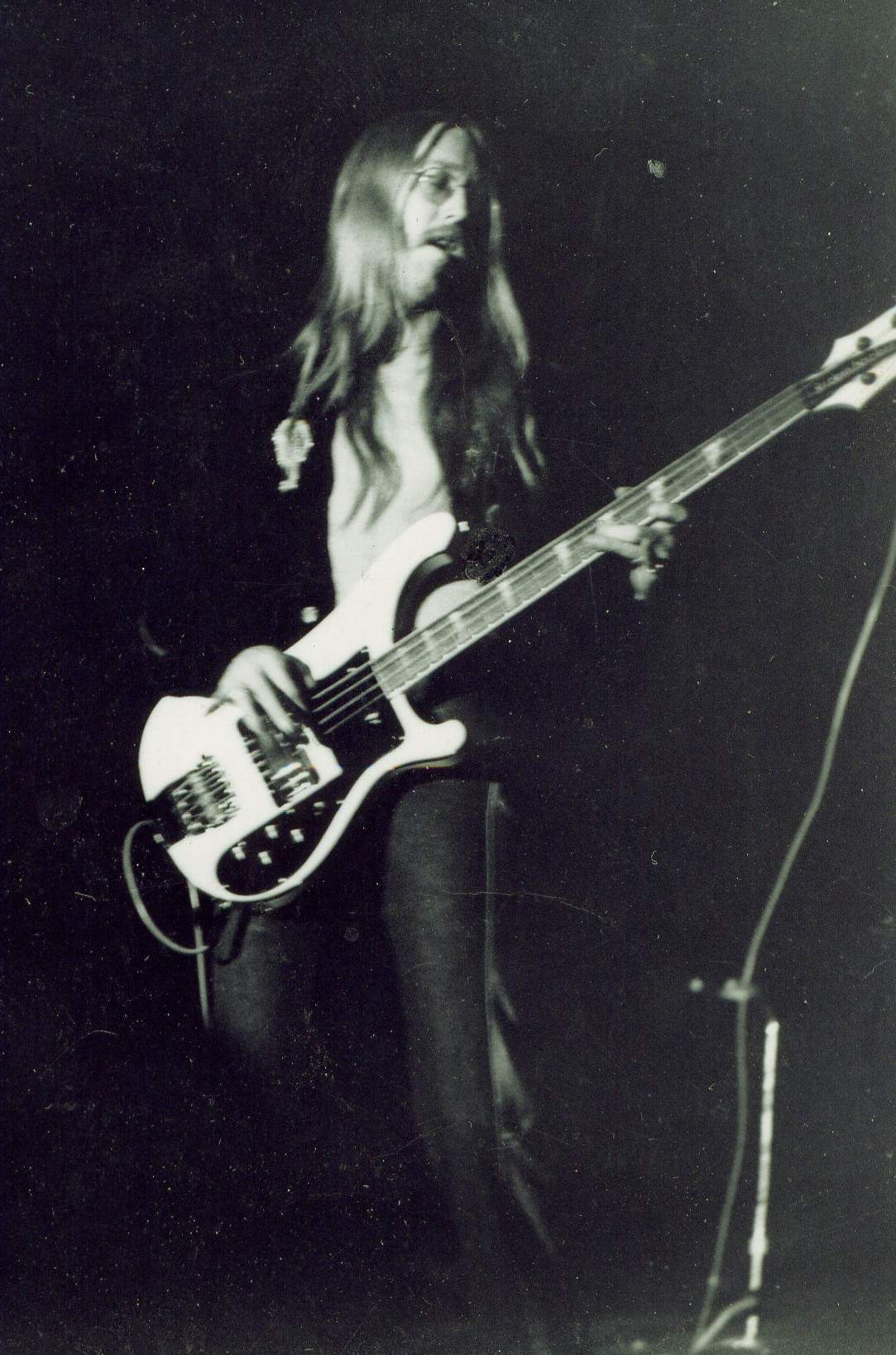

We played the outdoor Venice Pavilion on Venice Beach as the opening act for Montrose. It was a great time and is one of the few gigs for which there are actually a few photos. Austin says he still has an 8mm film of the gig that he has never had digitized and a cassette recording that he made, but I’ve never seen or heard them.

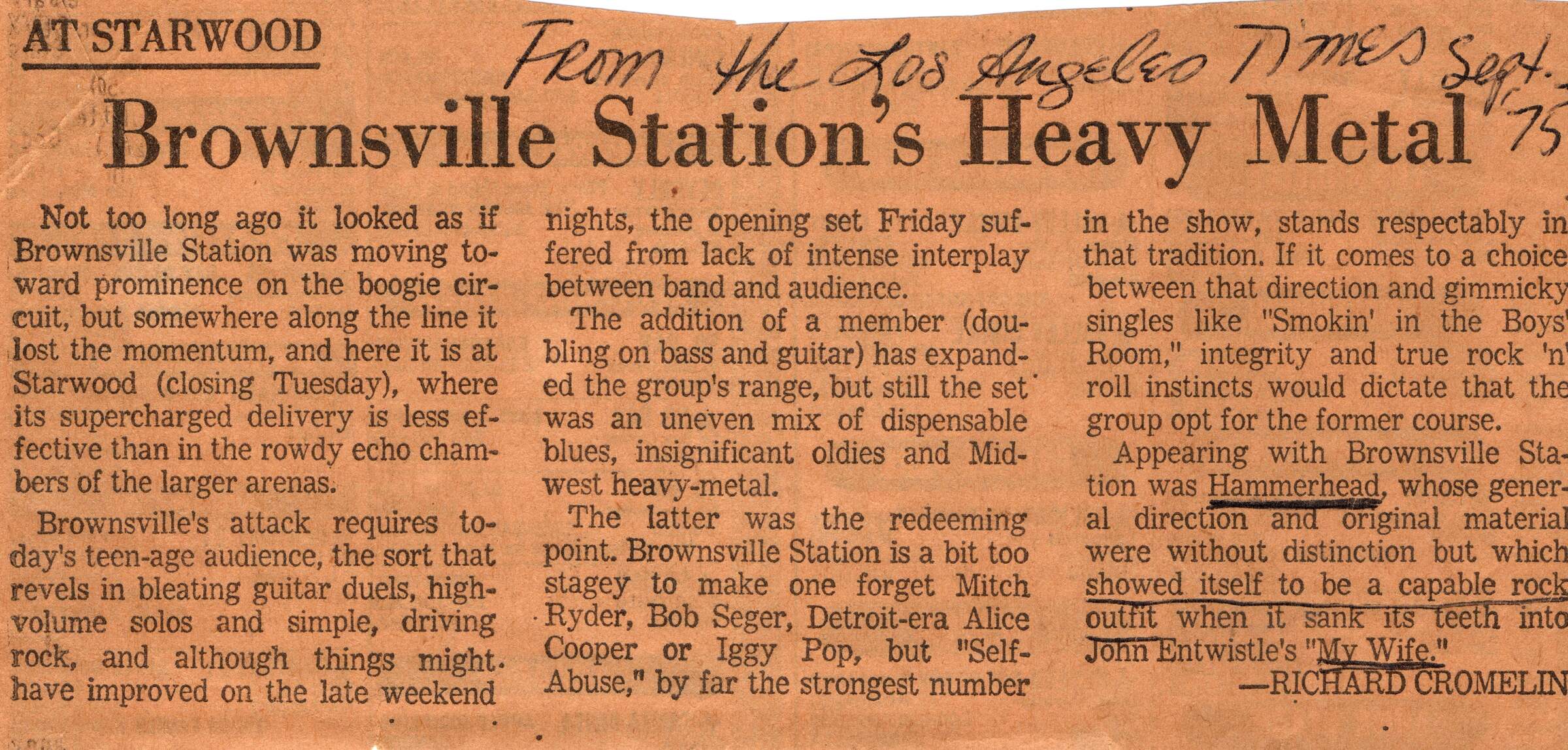

We were the opening act at the Starwood, probably the best rock club of that time in Los Angeles, for Brownsville Station’s Friday and Saturday night shows. As a bonus, we were booked as a headline act on the Thursday as well.

Tell us about ‘Summer Nites.’ Did Kim Fowley work with you on that track? What was his vision of the band?

Kim brought the band together at his home one afternoon. The place was small, and we were crammed into a rather tiny room that wasn’t really set up for rehearsing. I don’t recall if Terry even had his drums. Austin had his guitar and an amp, and I think I had my bass.

The general process of writing the song was led by Kim with Austin as the focal point of the music that was played. In fact, I don’t think the rest of us really needed to be there, but we did make contributions to the process. At Kim’s prodding, we (meaning mainly Austin) started improvising riffs and progressions. Kim would pick out things he liked and then suggest playing in the style of other bands like ZZ Top or Aerosmith. Austin’s diversity and creativity as a guitarist drove the process forward rather quickly. This went on for a while and ultimately evolved into the opening riff of ‘Summer Nites’.

I believe the session with Kim continued until we had established the basic elements of the song: the anchor riff, the chords for the verse, and the bridge. As far as I can remember, it was late in the afternoon when we left.

In the days after that session, the song evolved in rehearsals into its final form, and we started performing it, which allowed us to refine our individual parts, leading up to the subsequent successful effort by Kim to secure a recording contract.

I think Kim saw us as a unique mix of individual styles that yielded a dynamically strong musical product. We had a strong singer with a vocal identity who played to the audience. We had a solid rocker on guitar who projected a strong ego-presence from the stage. Terry was a basic drummer who had the two qualities that we needed most: rock-solid tempos and the ability to whiplash a song’s transitions from verse to bridge to solo and back. I made bass guitar an unmistakable presence that contributed melodic energy without (I hoped) overplaying. Together, we were formidable even though we had no gimmick.

After we signed with GNP Crescendo, it wasn’t long before we recorded the song. That was done in an evening session at Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood, the same place where The Beach Boys had recorded ‘Good Vibrations’. After my experience with Sudden Death at Columbia Records, the studio seemed small and was cluttered along all walls with a variety of amps and keyboards. Once we were set up, it was difficult to move around. I’m sure that the bass was fed directly to the board, so I could only hear myself through headphones.

Kim and GNP’s Neil Norman co-produced in the booth with a Gold Star engineer. We worked quickly, but it still took a couple of hours to set up, get the basic track work done, then record additional tracks with backup vocals and guitar solos.

What about ‘Jewels’?

‘Jewels’ was our singer Greg Sanford’s song. It may have been our first original. Its up-tempo pace, almost a cappella vocals with punctuated chords, and dynamic transitions made it another showcase song that we performed regularly.

‘Jewels’ was recorded at the same GNP recording session as ‘Summer Nites,’ but it wasn’t afforded the same amount of effort. We had laid down the tracks for ‘Summer Nites’ first, then turned to recording ‘Jewels,’ starting with a run-through to get into the song’s mindset and let the control booth do whatever they needed to do. As we played, I tried to reposition myself in the studio to get closer to Terry. Navigating all the equipment made it difficult to play at the same time, but I finally got where I wanted to be. I had missed coming in at the beginning of the song, and I’d made a couple of mistakes along the way, but now I was ready to go.

To my shock, Kim said they had recorded the run-through, and we were done. I was horrified. I told them I wasn’t happy with my performance, but they didn’t care. We were out of time. They did some quick overdubs, and that was it.

I was livid and gave serious consideration to sending my bass through the control room window. But I didn’t, and I’ve had to live with that track ever since.

Tell us about the gear, amplifiers, effects, and pedals you had in the band.

I started out with the gear I had been using since Sudden Death: a Gibson EB-3L bass and an Ampeg BT-125 bass amp, Ampeg’s first solid-state amp, with the matching Ampeg cabinet with two 12-inch speakers. However, I was still in touch with the Gallien-Krueger garage/factory in Northern California. As soon as their product line was available in Los Angeles, I bought their 600B amp and two reverse-loaded, folded horn Sunn 118MH cabinets (which were sold with a GMT identification plate rather than Sunn’s). I stacked the cabinets so they looked like a large horn, and let ’em rip. I seldom needed to turn the amp above 4.

The 600B came with a footswitch that engaged or disengaged features of the amp. It had a pushbutton to control an attenuation boost, and another to activate or suppress the distortion feature. That was it.

We experimented with using the Ampeg rig as an extension amp on Austin’s side of the stage, but it didn’t last.

When I broke my Gibson bass, I quickly bought a Rickenbacker 4001 bass so we could keep playing while the Gibson was being repaired. After that, I always had both basses on stage—the Ricky for all the energy songs and the Gibson for blues.

GNP Crescendo released your single. Did it get any airplay? Was there any talk about a possible full album?

I’m delighted to say that it did get airplay across the country. Kim and Neil explained that there were a dozen or so key radio markets, mainly in the Midwest and South, that were used by stations in major metropolitan areas to identify listener interest in new material. We got onto the playlists of several of those stations, making the top 30 in their markets, particularly in Panama City, Florida. That led to getting airplay on FM stations in Los Angeles, and more than once, I’d be driving home from a gig when I heard ‘Summer Nites’ on the radio. That was pretty cool.

There never was talk of an album, but there was some serious talk about putting us on tour in the South as an opening act for ZZ Top, but it never happened.

Crescendo did pick up its option to keep us under contract for a second year, but we never recorded for them again. After two years under contract and a single that received significant airplay, I never made a penny from the label.

“There are tapes we made of live gigs”

Are there any other recordings of Hammerhead unreleased?

There are tapes we made of live gigs, usually just a cassette recorder placed somewhere on stage. Austin has an audio tape of our set when we opened for Montrose outdoors at the Venice Beach Pavilion, and he also has an 8mm movie of the set. He talks frequently about restoring and digitizing both, and synching the audio tape to the movie, but he has yet to make that happen, despite my encouragement to do so before they deteriorate.

Terry occasionally made audio recordings at our gigs, I believe. I’ve never heard any of them.

But there is another virtually unknown “recording” of the band. Years before MTV and music videos became popular, Hammerhead was recruited by a group of students in UCLA’s media arts department to participate in a class project. They proposed to do an innovative video recording of the band. The plan was to do a live “master” video recording of us performing ‘Summer Nites’ in their studio, and then, using the playback of the soundtrack from the master, do a series of supplemental recordings of each member of the band performing the song using multiple cameras, capturing both long shots and close-ups focusing on things like that person’s hands, feet, and face. Then each of the individual videos, as well as the master group performance, were edited into its own distinct video. When played back simultaneously and in sync with the others, and viewed on separate monitors for each video, the result was a 5-screen multi-media experience of the band performing the song.

We spent hours working with the students to get all of the videos made, and then were brought back several weeks later to see the results. The students lined up five TVs in a row and then simultaneously played back the five synchronized videos. The results were stunning. I think it’s safe to say no one had ever seen anything like it at that time. The students had planned and produced the project so that scene changes swept back and forth across the five screens, or all changed at once, or went through complex montages somewhat randomly, but all in sync with the music. They did a great job.

I have no idea what happened to those videos. I hope the students all went on to make millions and careers shaping the world of music videos in the early ’80s.

How long did the band stay together? What happened to it?

Hammerhead lasted the better part of 3 years, from 1974 into 1977. Several dynamics seemed to contribute to its end. First, we decided—not unanimously—to become the house band at The Attic, which had changed its name to Boomers. I think we all felt that the club was our “home base.” It was where we started out, we had built a great stage, and we always drew enthusiastic, standing-room-only crowds. But it didn’t pay as well as other places, and it took us out of our regular appearances at showcase gigs in Hollywood.

Then there was dissatisfaction with the fact that I had taken a day job to stay afloat financially, which ultimately led to Terry giving me notice that the band had decided to look for a new bass player. I was pretty devastated by that news, but I agreed to stay with the band while they auditioned other bassists, either through tryouts or letting them sit in at gigs.

From that point on, I was somewhat disillusioned with the band and don’t remember much about what happened. The issue of adding another guitar player to the lineup resurfaced after being dormant since Jalon Lau’s brief time with us. Deniel Edwards joined the band for a while, but he didn’t last. Then came Bryce Mobrae. Somewhere along that timeline, I think Austin left the band, and we tried going with Bryce alone. But things were not rock solid.

Another factor might have been that GNP Crescendo picked up their option to keep us under contract for a second year but showed no interest in producing any more records, and no touring ever materialized. That lack of enthusiasm from the label that signed us and then picked up their option was deflating. It felt like we were back to square one. Hammerhead could easily have continued as a dynamic club band, but being under contract had become a selling point, and now it was gone. After all we had been through with Crescendo, we never did a gig outside the Los Angeles metropolitan area.

Ultimately, months after they had announced their intent to replace me, nothing had changed. I don’t know that they ever auditioned another bassist; no one ever sat in at a gig that I remember. And no one ever told me that the band had changed its mind about firing me. So I finally notified the band that I’d play out the remainder of our bookings, which meant another 2 or 3 months, and then quit. Part of me hoped that they’d make an effort to reconcile and keep things going, but they didn’t. The band did not survive my departure.

You also experimented with adding Jalon Lau on violin? How did that go?

John: Original member Woody Woods was a die-hard blues player, but after several months of gigging, it was clear that Austin’s desire to be a hard rock band, coupled with the full-throttle energy that Terry and I were producing, was the direction we were heading. Woody became dissatisfied and left us. At that time, with the band still just starting out, Austin wanted to maintain the two-guitar format, so we started auditions.

Jalon showed up and seemed like an oddity, but when he started playing, we were knocked out. He had a hard rock guitarist’s approach to playing the violin, and he could watch Austin’s fretboard and ad-lib violin parts to songs he didn’t know. His leads rivaled Austin’s. It was amazing.

So Jalon joined the band, and we started doing gigs with him. I thought it was something special and unique for the band, putting us almost in a hard-rock fusion format. I remember I had been exposed to the Mahavishnu Orchestra by Keith in Sky Fire, so I was on board. But for some reason, only after a matter of weeks, Jalon left us. I never saw him perform again. And it was several years before the need for a second guitarist was rekindled.

How did the lineup change after that?

After Jalon left, we stabilized as a power trio with a singer for almost the entirety of our existence. It was only in the late stages of Hammerhead’s lifetime that an effort was made to alter the lineup with guitarist Deniel and then Bryce.

What followed for you and other members of the band?

I immediately went to work with my closest friend, Pete Castle, to form a new band. Pete was a phenomenal guitarist, so much so that he had been sought out by Eddie Van Halen for lessons. Pete was amazing. He had heard Hammerhead and was drawn to its success, and we became fast friends. He had only been in one band and was timid about jumping into the limelight, but he and I started hanging out together, checking out bands when Hammerhead wasn’t playing. Gazzarri’s had a storage room upstairs behind the upstairs stage, which musicians used as a green room. A lot of impromptu jam sessions happened in that room, especially when Hammerhead and Van Halen were both playing in the club. The likes of Eddie Van Halen, Austin, George Lynch, and Randy Rhoads might be heard there on any given night, back when the only musicians in the room who were in bands that were signed to a label were Hammerhead’s. Pete could hold his own with all of them. It was fabulous.

So when I left Hammerhead, Pete and I hastily put together the band Zzip with Greg Sanford as vocalist (yes, from Hammerhead) and a guy Pete knew named Lenny on drums. I booked us into Gazzarri’s, with no audition necessary, less than a month after our first rehearsal, and we just destroyed the place with a song list dominated by Rainbow, Kansas, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and Queen. A week later, we headlined at a locally produced concert at the Culver City Civic with similar impact. But after that, Pete and the drummer decided Zzip wasn’t for them.

I was pretty depressed about the state of my musical career until I found a young guitarist in the San Fernando Valley and joined his band, F.I.S.T., and stayed with them for a year and a half. That was a party band, playing almost weekly at private parties and making good money in tips, even though we never had a singer. While in that band, we had a guy named Audie Desbrow on drums for a stretch, who went on to become the drummer in Great White.

During my time in F.I.S.T., Joey Dunlop (Sudden Death’s guitarist) reestablished contact with me, and it didn’t take much persuasion for me to leave F.I.S.T. and rejoin with him, forming Temper with Dave Dickerson on drums. We went through a series of singers without finding the “right” guy, worked sporadically at a wide range of clubs, and made a poorly produced “demo” with one of our singers. But the same dynamics that had broken up Sudden Death emerged with Joey’s disinterest in playing clubs, and we broke up around 1980.

In the late ’70s, I was also involved in a very informal project with a friend of Pete’s who lived in La Canada. He was trying to put together bands to play at frequent parties in the area, and I teamed up with him. He was playing all the right songs and could kill it on just about anything. Every rehearsal started with ‘Highway Star,’ and it was hard to imagine anything better. That was Chris Holmes, who went on to become the guitarist in W.A.S.P.

Greg, after his one gig with Zzip, went on to join George Lynch’s band The Boyz, which then morphed into Xciter, and included Mick Brown on drums and Monte Zufelt on bass. They immediately began showcasing themselves at the Starwood, became a huge draw, and recorded a stunning 8-song demo that includes Xciter’s own take on ‘Jewels,’ the B-side to Hammerhead’s ‘Summer Nites,’ and the original version of ‘Paris Is Burning,’ which was eventually recorded live by Dokken. Xciter broke up when George and Mick were recruited to join Dokken. That was the last I heard of Greg for years.

I lost touch with whatever Austin and Terry did musically in the aftermath of Hammerhead. Terry bought and managed Boomers for several years, trying to turn it into something of a showcase venue. He also organized a 10-year reunion of the band in 1987 at a nice rehearsal facility, and everyone showed up, but other than a nice night of playing some of our songs and reminiscing about the good old days, nothing came of it.

The last time I saw Terry was at a Boomers reunion in 2014 to which he invited members of all the dominant bands who ever played there, including Hammerhead and Van Halen. The reunion was held at a nice club on Venice Beach and drew around 30 musicians and a packed house (no one from Van Halen attended). Austin didn’t show, and Greg was there but only sang a couple of songs, but Terry and I did the lion’s share of work as the night’s rhythm section, and it was great to work with him again. He passed away in 2023.

What currently occupies your life?

Here in 2024 with my wife, Ellie, it’s mainly about trying to balance personal time with frequent opportunities for quality time with our 4 grandchildren. I’ve been inactive as a musician for several years, but I see opportunities ahead to get back into it. At least I’m healthy and active, so we travel when we can, and the rest of the time is devoted to the several personal projects I always seem to have in the works.

What would be the craziest story that happened to the band?

For me, it was the night I broke my Gibson on stage. We were at the Handlebar Saloon in Pasadena, a terrific venue in the style of an upscale, old west saloon. The stage wasn’t large, but the downstairs had a vintage bar, a large dance floor, and plenty of saloon-style wood tables and chairs. On two sides of the club, opposite the bar and opposite the stage, there was a 2nd-floor balcony with additional seating. It was a great place.

We were playing a song that had a rhythmic break in the middle with just drums. We’d all grab percussion instruments to groove on, so I slung my Gibson behind my back as I had many times before. Sure enough, right in the middle of things, my strap slipped off the bass, and it fell to the floor.

No worries, though. I picked it up, and it looked intact, so I only needed to check its tuning before we had to come in. The E string was a little flat but came to pitch okay. The A was worse, so I gave the tuning peg a twist, and… SNAP. The next thing I knew, the bass’ machine head was dangling from strings around my knees, and I was looking at a stump of a neck, splintered just above the nut.

What was I going to do now? The bass that had served me so well through Sudden Death, Sky Fire, and now Hammerhead, was dead. The crowd on the dance floor in front of us was staring in disbelief.

Austin was quick to react. He reached into his gig bag and tossed me a roll of duct tape. “Tape it up!” he shouted. So I pulled the strings off the machine head, jammed it back onto the end of the neck, and wrapped it up with duct tape just above the nut. I pulled all the strings off the bridge except the E string, fed it into its peg, and tuned it up to E. The tape held, and I played the rest of the night on that one string.

The problem then became our schedule. We had gigs booked the next weekend, and even though I got the bass to a repair shop on Monday, it was going to be a couple of weeks before they could have it fixed. So I put up my car as collateral, took out a loan, and bought the bass a lot of people had been urging me to consider for some time: a Rickenbacker. On Tuesday, I went to HFC, took out a loan, and then went to Guitar Center to buy my white 1974 4001. I was back in business, but also in debt.

The Ricky was terrific and had immediate impact. The sound of the band changed in a very positive way, and I settled in quickly with the bass and its awesome sound through the GK setup. The Gibson was repaired amazingly well, so much so that you couldn’t see the break. While in the shop, I had them modify the electronics, put on a Badass bridge, and paint it black to contrast with the white Ricky.

This tale doesn’t really end there, however. The Ricky wasn’t three months old when we had finished a gig at The Attic. In the aftermath of our closing, a few girls were on the dance floor, energized by music from the club’s jukebox. They were drunk, and one of them stumbled into the stack of PA speakers on my side of the stage. They toppled over and fell in a heap onto my equipment. When we pulled my gear out, the Ricky’s neck was broken just like the Gibson had been, snapped off just above the nut.

This time, I approached the repair differently, mainly because it was so new that I thought I might get some kind of warranty repair. The Rickenbacker factory was in Santa Ana, an hour’s drive down the Santa Ana Freeway, so I took the bass there. I explained my situation to a receptionist, with a larger-than-life photo of Chris Squire on the wall behind her, and she said a technician would come to take a look. In a few minutes, a guy who must have been 70 years old came out, and I opened my case to show him the damage. He actually gasped when he saw it. I explained my predicament: a new bass, a busy schedule, no money, already in debt. He told me to wait, closed the case, and took it back into the factory. I didn’t know what to expect.

About 10 minutes later, he came back with the case. He opened it, and the bass was fixed! But, as he explained, not really. What they had done was remove the plate with my bass’ serial number, put it on a new bass, and restrung that bass with my strings. They couldn’t do it for free, however, but they charged me the wholesale price of a new neck, with no labor. So I was able to put the Ricky back in service at our next gig for just $175.

“Opening for Montrose was also a highlight gig”

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

Well, the Friday/Saturday-night gig at the Starwood with Brownsville Station was a tremendous event for us. A packed house at a Los Angeles showcase club, opening for a touring band, felt big-time. The Los Angeles Times’ top music reviewer came to a show and gave Hammerhead a brief, lukewarm mention in his article on Brownsville Station, but like hearing our song on the radio, it was just great to see the band included in a review of any kind.

Opening for Montrose was also a highlight gig. It was outdoors at the Venice Pavilion, right on Venice Beach, and it might have been the biggest single crowd ever for the band. It didn’t have the glamour of Starwood gigs, but playing for that many people as an opening act for a band with that much recognition was thrilling.

Richard Fazekas promoted a concert at the Culver City Civic with Hammerhead as the headline act and a couple of popular local bands as opening acts, but he relied mostly on word of mouth for publicity. While successful, it didn’t draw any widespread interest.

Hammerhead was recruited by Sorcery to be their backup band for several gigs. They were in their early years as a conceptual stage act, but it was exciting. Because of their elaborate stage setup, they only played venues with large stages, so every show felt like big-time. They rehearsed at a Bekins Moving and Storage warehouse in Burbank. It was a huge place, and they had rented a large area of the floor for their stage set and rehearsals, so we had the opportunity to integrate the music with their stage act, which took some getting used to.

We had two of the most memorable New Year’s Eve gigs I ever did. Both were played for the huge parties thrown by the fans of the Big 10 football team playing in the New Year’s Day Rose Bowl game. Both gigs were for fans from Ohio State.

The parties were held in the ballroom at The Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. It was madness. There were 40 or 50 round banquet tables set up in the ballroom, along with a large dance floor in front of the sizable stage. These kids from the Midwest were in Los Angeles, cutting loose on New Year’s Eve. They brought hundreds of bottles of liquor to the party and drank it all. The cheerleaders were there to keep things going during our breaks. We let loose with our show and blew them away. It was almost unreal. Spring break on steroids.

I did a side gig with Neil Norman that significantly modified my view of audiences. Neil had released a couple of albums as Neil Norman’s Cosmic Orchestra, featuring rock versions of music from the soundtracks of sci-fi television shows and movies. His albums got some traction, and he would rent booth space at Star Trek and sci-fi conventions to promote them. He approached me while I was in Hammerhead with a new promotional idea: have a live band to promote the album, and he wanted me to play bass. I was given a copy of the album and some chord charts to prepare for practice on a Wednesday before playing the following Saturday at the show.

The idea of playing in a booth at a Star Trek convention seemed novel to me, and I was excited about the opportunity, but things didn’t go well at the rehearsal. Neil had recruited a drummer, a guitarist, a keyboardist, and me to comprise the band along with him, and we weren’t able to get completely through any of the songs without the effort falling apart. We worked at it for a couple of hours, to no avail. Neil, however, wasn’t discouraged. He said he still wanted to promote the albums with a band, but that we’d just bring our equipment and mime the music to a playback of the songs, and that would be good enough. It sounded weird, but it still sounded like fun.

So on Saturday, I showed up a couple of hours early at the Airport Mariott Hotel. I had no instructions on where to go to unload my equipment, so I boldly drove up to the front of the hotel, parked in a spot for guest registration, and went in to find out what to do. Taking a bass with me to look important, I went straight to the front of the line at a security checkpoint and told a security guard that I was with Neil Norman’s band and needed to know where to go. He got on a walkie-talkie, then led me through the lobby and down a flight of stairs to where, I supposed, the convention was. There were lots of kids and adults walking around in costume with bags full of goodies from the convention. We turned into a long, wide hallway where a very large number of people were sitting on the floor. I assumed a celebrity was expected to make a personal appearance and asked the guard what everyone was waiting for. As he opened a door to what I supposed was the convention, he said, “The band. You guys are the main event.”

The door I went through didn’t lead to the convention. It led to a huge meeting/banquet room, completely filled with rows of folding chairs in front of a very large stage. And on that stage was Neil Norman, setting up a stack of Marshalls and keyboards. It took me a moment to let all this sink in. We weren’t going to be playing in a cramped space on the convention floor; we were the evening’s main attraction, on stage in front of a large audience. And we weren’t going to be playing for real.

Neil told me where to go to unload equipment, so I moved my car, rolled my gear in, and set up my GK stack. The rest of the band arrived and set up, and once everyone’s equipment was set up, Neil started stringing a series of connections between his tape player and our equipment. “We’ll feed the music through all of our equipment so it sounds more real,” he said.

At 8:00, the doors opened and the crowd streamed to the seats in a rush. Neil had a wardrobe of space suits and whatnot for us to wear, and at about 8:15, the lights went out, we took the stage, an announcer welcomed everyone to Neil Norman’s Cosmic Orchestra, and as the applause died down, the drummer clicked four beats of tempo, and Neil pushed “Play.” I prepared for the worst.

What happened for the next 45 minutes stunned me. The audience bought our show hook, line, and sinker. I couldn’t believe it. Everyone on stage did their best to cover their asses, selling the show with performance and interaction, and the crowd loved it. We survived. In fact, after the show, we were treated like celebrities, signing autographs and answering a barrage of questions about the band and the music. I packed up and left with a huge sigh of relief and a new perspective on audiences. Years later, I would hear Sandra Dee’s advice to Bobby Darin that would seem to apply to my experience: “The audience hears what it sees.”

We did another, smaller-venue convention gig a year or so later, but for that, we just wore outfits, did cover songs, and played live.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style, and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

I’ve gone into some depth answering this question in my Sudden Death and Sky Fire interviews. To that, I’ll add that I continue to listen to and draw from contemporary bassists, besides those who played a role in my formative years. Listening to how guys like David Ellefson (Megadeth), Stefan Lessard (Dave Matthews Band), Jay Bentley (Bad Religion), and Brian Marshall (Creed) combine energy with musical elegance challenges me to move forward with my playing. I’ve been to concerts to watch them play and soak in their interactions with the band and audience. There’s always something new to learn, you know.

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

That would be luck. It was luck as much as anything that saw my musical experience evolve from its raw beginnings in Sudden Death to a broader experience in Sky Fire, and then to the success we enjoyed in Hammerhead. I was lucky to find myself, from early on, drawn into the music business on a level that put the possibility of commercial success within my grasp. I was lucky to work with and befriend some of the finest musicians anyone could ask to encounter. I was lucky that ultimately, though briefly, I found myself in a band signed to a record label, and hearing our song on the radio.

I was lucky to know what it’s like to be in a band that had a large, devoted following, and to play in top-notch showcase venues in one of the most competitive markets in the country. We struggled through it all, rehearsing in a one-room remote cabin in Topanga Canyon for a while, but we’d put the results of that effort into a dynamic on-stage experience.

I’ve been lucky to have known and played gigs with a lot of people who became household names in rock. When I lived in Hollywood, we were on such good terms with Van Halen, Quiet Riot, and Xciter that we’d hang out together at my place and watch Star Trek, or go to Dodger Games, and the like. Blackie Lawless (W.A.S.P.) would write songs and have me come over to his place to work out bass lines for them. Greg Sanford’s brother, Rick, and his band Banshee briefly lived at my bungalow home in Hollywood when they came to town. Rick went on to be the lead singer in Legs Diamond. It was so casual, and I was so lucky to have shared such great times with them all. We were brothers in a music scene that was exhilarating and would launch the careers of many of us.

Today, I’m lucky that anyone is interested in the stories from that time. The renewed interest in Sudden Death, and the follow-on tales of Sky Fire and Hammerhead, are as much as anyone could hope for after 50-plus years.

But in retrospect, the real luck that fell on me from those days was meeting Terry Brent, who brought Kim Fowley to hear Sudden Death at a house in South Pasadena, and eventually recruited me to be in his band, Hammerhead. His influence and participation in my story as a musician were massive. You just never know. Rock On!

Klemen Breznikar

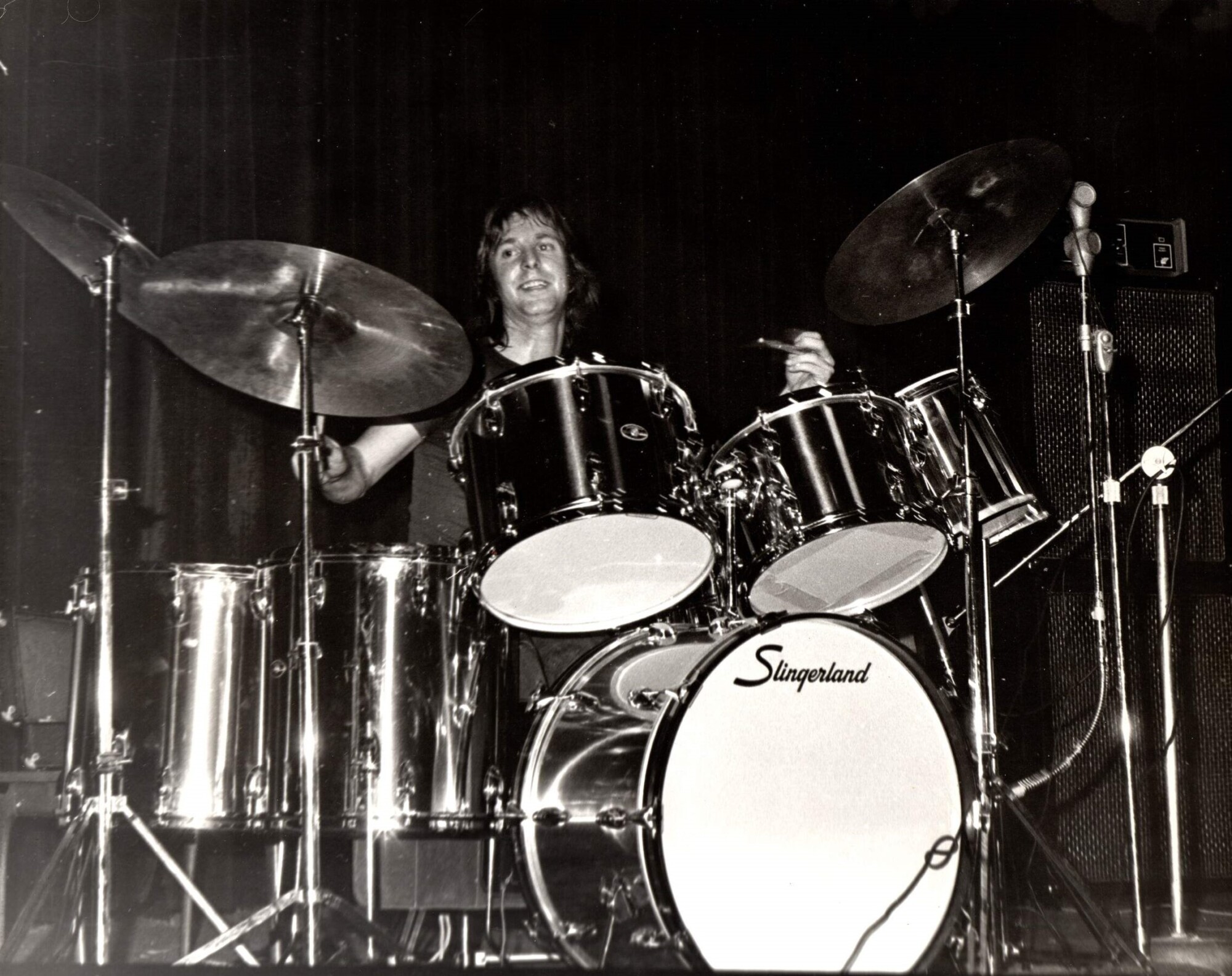

Headline photo: Hammerhead at Venice Beach Pavillion, opening for Montrose

Sudden Death | Interview | “America’s Answer To Black Sabbath”