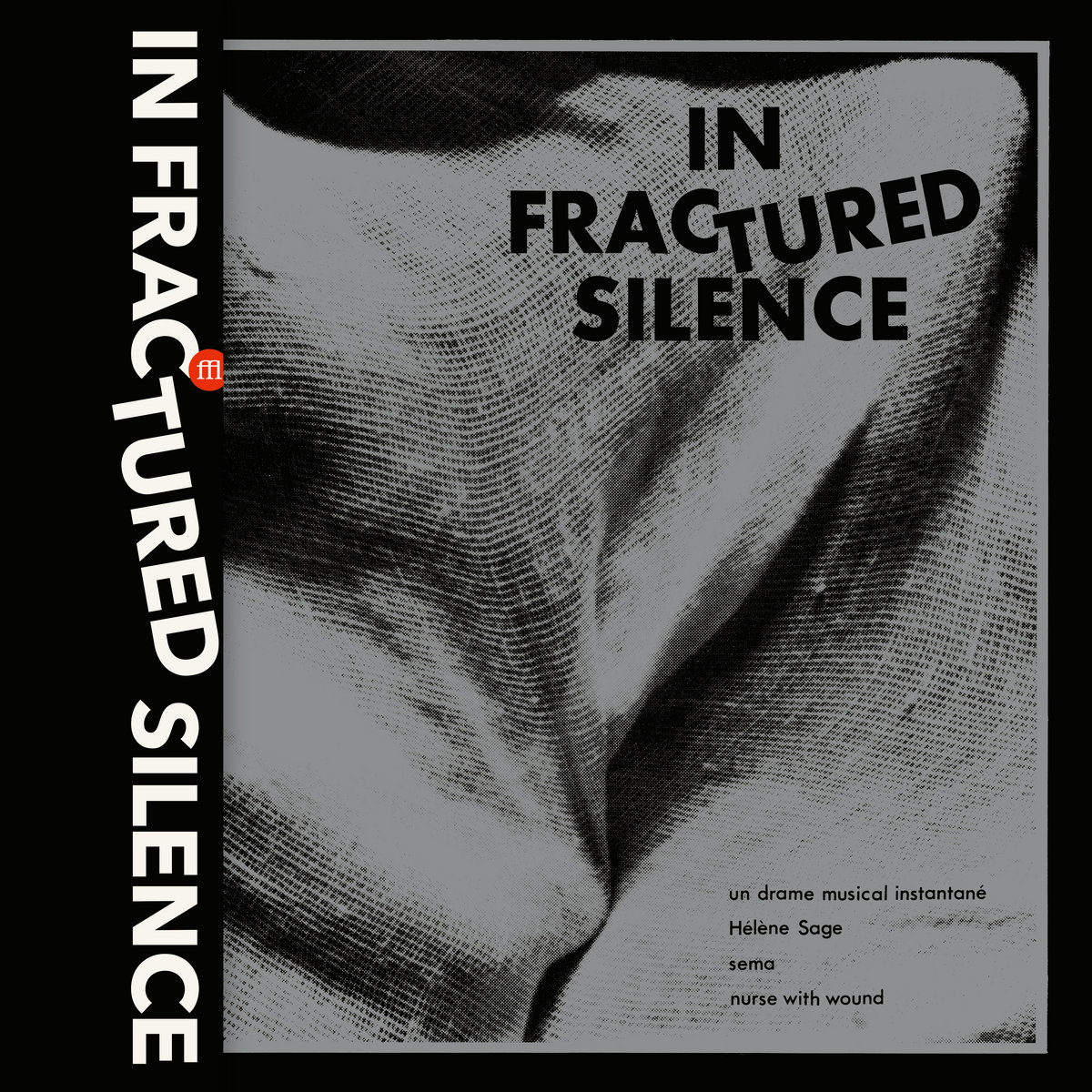

In Fractured Silence

If you’re a seeker of the obscure, the avant-garde, and the downright peculiar in the realm of music, then you’ve likely danced along the edges of the Nurse With Wound List. Within this labyrinth of sonic exploration lies a treasure trove curated by the eclectic mind of Steven Stapleton.

And amidst its tapestries of sound, there resides a few enigmatic figures whose melodies linger like whispers in the wind.

Enter Jean-Jacques Birgé and Francis Gorgé, heralds of the unexpected, whose album ‘Défense de’ caught Stapleton’s ear like a siren’s call. It was this sonic tapestry that paved the way for Stapleton’s journey across the channel to France in 1980, seeking contributions for his brainchild, the United Dairies label.

The result? An opus titled ‘In Fractured Silence,’ where musical boundaries blur and avant-garde reigns supreme. With Un drame musical instantané leading the charge, listeners are plunged into a maelstrom of synthesizers, percussion, and ethereal vocals, leaving mystery in its wake.

Then, like a whisper in the dark, Hélène Sage takes the stage, crafting delicate chamber music that dances on the edge of silence. Meanwhile, across the channel, Sema’s piano weaves a tale of daring melodies and dark requiems, before Stapleton himself emerges from the shadows, transforming female voices into an iconoclastic symphony.

From the haunting melodies of Un drame musical instantané to the avant-garde reveries of Sema and Stapleton’s sonic alchemy, ‘In Fractured Silence’ beckons you to choose a side in this musical journey through the corridors of the unexpected.

Carefully restored and remastered by Gilles Laujol, with graphic design by Stefan Thanneur, this heavyweight 180 gr. reissue LP by Souffle Continu Records is housed in a 425 gsm brownboard outer sleeve. It’s more than just a record; it’s a portal to a world where music defies convention and embraces the unknown.

So, dear reader, dare to step into the fractured silence, and let the music guide you on a journey beyond the confines of ordinary sound.

“We let the inspiration of the moment guide us”

Jean-Jacques Birgé and the formation of Un Drame Musical Instantané.

Jean-Jacques Birgé: In 1981, after François Mitterrand’s election as President of the Republic and Jack Lang’s appointment as Minister of Culture, the cultural budget represented 1% of France’s budget, which is enormous compared to what is practiced today. I received a phone call from the Music Directorate asking if Un Drame Musical Instantané had an artistic project because there was too much money to allocate! Overnight, we set up an association and proposed the grand orchestra of the Drama that we had just created. The grant allowed us to sustain this orchestra of fifteen musicians for six years. This period also marked the golden years of Radio France, initiated by Alain Durel and Louis Dandrel. Thus, for France Musique, Didier Alluard and Monique Veaute proposed that we produce two creation programs of over two hours each where we were totally free. The national radio gave us access to its archives and provided us with two fantastic assistants, Bernard Treton and Christine Bessely, as well as a sound engineer to mix everything, Alain Nedelec, and a sound effects artist, Dominique Auber, although I handled most of it myself.

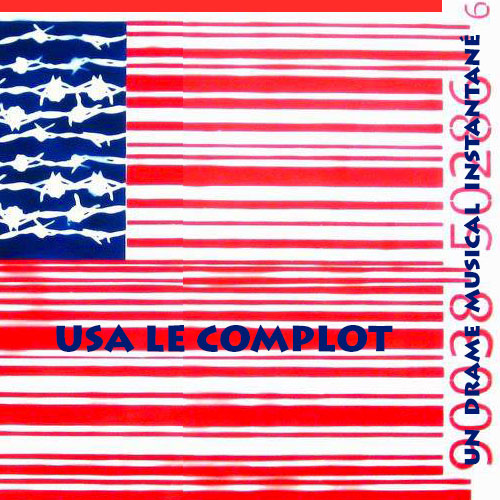

‘USA le complot,’ the first creation of Un Drame Musical Instantané, was broadcast on June 17, 1983. The trailer we composed said: “The history of the USA resembles a western. The settlers came with nothing. They had to take. First, the Indian lands, and the jazz of African slaves, and the raw materials of the third world. America became strong. It has a sense for business. What was stolen had to be sold. Americans have a sense of hospitality: they are at home everywhere. Genocide, segregation, witch hunts, imperialism…

From the United States of America, there resounds around the globe a strange music that pretends to be deaf to what is happening elsewhere, where it’s a different story… U.S.A., the plot. A program created by Un Drame Musical Instantané. Jean-Jacques Birgé, Bernard Vitet, Francis Gorgé. Friday, June 17, from 10:30 PM to 1 AM.”

The program was essentially made up of pre-existing sound and musical documents: Mothers of Invention’s ‘God Bless America.’ Music of the Navajo Indians. Artillery batteries from Rochambeau’s Expeditionary Corps. John Ford and Samuel Fuller. Peyote chant of the Yankton Sioux. Claims of Indian tribes. John Philip Sousa’s ‘Galant 7th.’ Buffalo Bill. Testimonies from Jean and Geneviève Birgé. ‘Run Of The Arrow,’ music by Victor Young. Women’s chant from Burundi. Aretha Franklin’s ‘Mary Don’t You Weep.’ Steve Reich’s ‘It’s Gonna Rain.’ The Last Poets’ ‘New York New York.’ Colette Magny’s ‘Oink Oink.’ Ruben and The Jets’ ‘Almost Grown.’ ‘News On The March.’ Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Star Spangled Banner.’ Charles Ives sings ‘They Are There.’ ‘Rocker’ by Charlie Parker in support of the American Communist Party. Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis’ ‘Bag’s Groove.’ Albert Ayler’s ‘Spirits Rejoice.’ Cathy Berberian’s ‘Stripsody’ performed by Marie-Thérèse Foy. The Wall Street Journal on French culture. Bertolt Brecht before the House Un-American Activities Committee. ‘Johnny Guitar,’ ‘Vera Cruz,’ ‘A King in New York,’ Tex Avery, ‘Underworld USA.’ Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney. Johnny Hallyday’s ‘La bagarre.’ Serge Gainsbourg’s ‘Comic Strip.’ Michel Jonasz’s ‘Big Boss.’ Karen Cheryl’s ‘La marche des machos.’ Adriano Celentano’s ‘24000 baisers.’ Nina Hagen. Los Bravos’ ‘Black is Black.’ Pyramis. YMO. Ryo Kawasaki and The Golden Dragon. Miles Davis’ ‘Solea.’ Harry Partch sings ‘The Letter.’ Spike Jones’ ‘Hawaiian War Chant.’ Terry Riley and John Cale’s ‘Church of Anthrax.’ Laurie Anderson’s ‘From The Air.’ Charles Ives’ ‘Variations on America’… At that time, the end of the broadcasts was marked by ‘La Marseillaise’ in Berlioz’s orchestration, it was fitting in this case! At night, the broadcasts would stop.

‘La peur du vide,’ the second creation of Un Drame Musical Instantané, was broadcast on July 1st, 1983. Same team, but this time the Drama inserted itself into the program with four original pieces composed specifically: ‘La peur du vide,’ ‘Légitime Défense,’ ‘Le directeur paiera pour ses crimes,’ and ‘Tunnel sous la Manche.’ The chosen style was that of a thriller. Apart from the pieces recorded in the France Musique studio by the three of us, the two hours and thirty-three minutes included Arnold Schönberg’s ‘Die eiserne Brigade,’ Edgar Varèse’s ‘Ionisation,’ Camille Saint-Saëns improvising on the piano for ‘Samson et Dalila,’ Hector Berlioz’s ‘La damnation de Faust,’ ‘Pandemonium,’ ‘Sérénade,’ Charles Trenet’s ‘Joue-moi de l’électrophone,’ Les Frères Jacques’ ‘Monsieur William,’ Claude Nougaro’s ‘À bout de souffle,’ Georgius’ ‘Monsieur Bebert,’ Marianne Oswald’s ‘Anna la bonne,’ Bernard Vitet’s ‘La guêpe, le rêve de Robert Desnos,’ ‘Légitime Défense,’ Guillaume Apollinaire, Michel Poniatowski, Jean-Paul Sartre. ‘Une femme est une femme,’ ‘Masculin Féminin,’ ‘Tristana,’ ‘Le testament du Dr Mabuse,’ ‘Dial M for Murder,’ ‘L’éclipse,’ ‘Le parfum de la dame en noir,’ ‘Underworld USA,’ ‘Pick Up on South Street,’ ‘Shock Corridor,’ ‘Naked Kiss,’ ‘Le trou,’ ‘Le testament d’Orphée.’ An instant musical drama ‘M’enfin, Le malheur,’ unpublished from our grand orchestra! At the end of the broadcast, we chose Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli’s version of ‘La Marseillaise.’ Silence settled on the airwaves until the early morning.

The complete lineup of Un Drame Musical Instantané was:

Jean-Jacques Birgé – PPG Wave 2.2 synthesizer, piano, trombone, trumpet, reed trumpet, flute, jew’s harp, percussion

Bernard Vitet – trumpet, violin, percussion, piano, reed trumpet, double bombard

Francis Gorgé – electric guitar, bass guitar, analog synthesizer, flute, percussion, piano

When Steven Stapleton asked us for a piece for the collective album ‘In Fractured Silence,’ we were so pleased with what we had recorded for this radio creation that we offered him ‘Tunnel sous la Manche’ (Under The Channel).

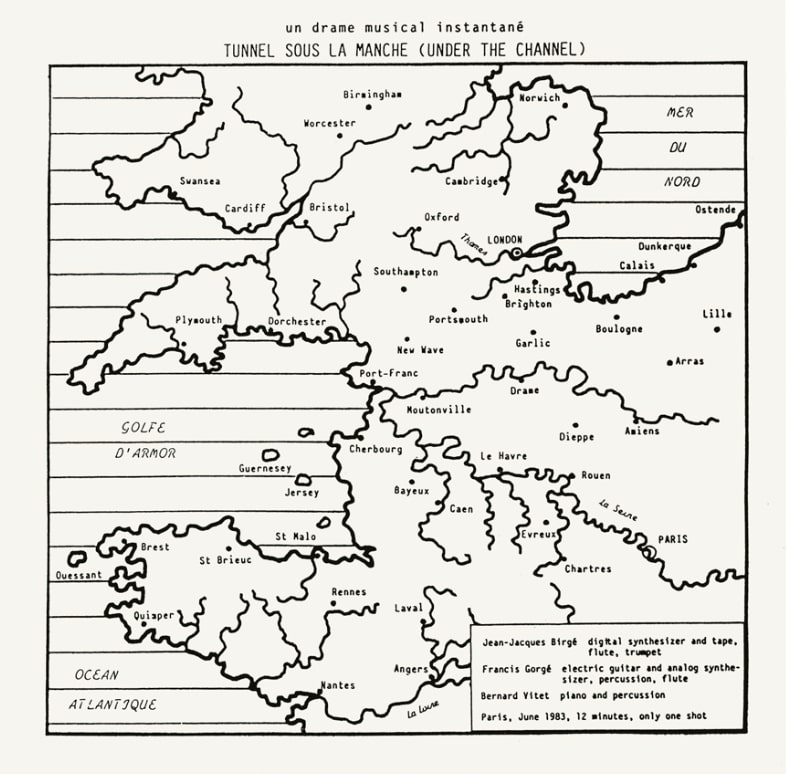

On one hand, I leave it to Steven to tell how he chose us, and on the other hand, I don’t think the piece was originally named like that, but I forgot. All of that is very distant now. It was forty years ago. Our mischievous spirit led us to rename this piece, probably to mock the prejudices of the English, whom we called on our side “the hereditary enemy,” towards the French. With the same humor, Francis drew a map where England was no longer an island, and we imagined new cities like Garlic, New Wave, Drame, Port-Franc, Moutonville… I remembered an old headline from The Times, “Storm over the Channel, continent isolated.” ‘In Fractured Silence’ was released in 1984, but the four pieces are included as bonus tracks on the CD ‘Rideau!,’ released by the Austrian label Klanggalerie in 2017, but now already out of print. The version of ‘Tunnel sous la Manche’ there is a bit longer, lasting 14 minutes instead of the 12 minutes recorded on United Dairies. I probably cut something to respect the duration of the side.

To comment on ‘Tunnel sous la Manche’ (Under The Channel), I am obliged to listen to it again. I only remember that every time we played at Radio France, we took advantage to request the Bösendorfer Imperial piano, which has nine extra keys in the bass and costs a pretty penny of €200,000, as well as percussion instruments such as the symphonic bass drum, the symphonic tam-tam, bell plates, and sound effects like the wind machine. I also brought a recording of the soundtrack from Jacques Becker’s fabulous film, “Le trou,” which tells the story of an escape from La Santé prison in Paris. In my early days, there was no video. VHS didn’t exist yet. To keep a record of films, I would record the sound of movies in theaters or on television with a portable cassette recorder.

The piece begins with Bernard Vitet on the piano while I play on my PPG Wave 2.2, a German digital synthesizer that operates on wave tables and was not yet MIDI-compliant. MIDI would come for me with the advent of Yamaha’s DX7. Afterwards, I never found the sonic transparency of the PPG with any other instrument. I still have it, although I don’t really use it often. I play the flute at the same time, true to my Shiva or Kali side. Francis is obviously on electric guitar. We first play according to the principle of blocks interspersed with silences. I notice the great complicity between us, a way of being oneself and together. That’s what has always fascinated me about Francis, able to catch the worst balls I threw at him. As for Bernard, he taught us about silence. It’s funny to note that he never plays the trumpet here, even though it’s obviously his favorite instrument. I start the soundtrack from “Le trou” which begins with hammer blows on a stake to dig the tunnel while I strike my keyboard. The dialogues from the film correspond to a kind of self-description of the Drama: “- You know it’s not possible. – But yes, precisely, that’s what will save us, it’s the noise!” I change registers, switching from pseudo-brass to grand organs. Francis takes a flute and I take my pocket trumpet, which is not usual for either of us. Francis hits a gong and bell plates. Bernard was a fan of Thelonious Monk and Anton Webern. I take a vibraphone sound. I think one of the actors says “Go on, Jo!” but I hear “Go on, play!” Percussions and piano blend with the sounds of prisoners digging. We follow the action by articulating the play. Francis grabs a bottleneck. I let the tape run. Bernard then switches to percussion. We breathe. The piano, guitar, and PPG return. Francis doubles with an analog synthesizer. It’s over.

Since the beginning of our encounter as the three of us, when I listen to us, I am surprised by the freedom we grant ourselves and by the mastery of time and structures, to the extent that we will reject the overused term “improvisation” in favor of “instant composition.” Improvisation is about minimizing the time between conception and performance. At the same time, we mainly composed for our grand orchestra. I had tried to apply the rules of the trio to the ensemble, but it didn’t work. I was dismayed by the number of clichés that collective improvisation generated. So, we increasingly wrote from there, in order to experiment with new things. When we found ourselves in a trio or in a small group, with Hélène Sage or Gérard Siracusa for example, we let the inspiration of the moment guide us, but more and more, we had a narrative framework or roles to assume, like when we accompanied silent films.

While reading Steven Stapleton’s notes on the reissue of Le Souffle Continu, I discovered the circumstances of all that, which I had completely forgotten. Steven and I have reconnected, and he has just asked me to remix one of his compositions for a Nurse With Wound box set to be released next year. On my side, I have started recording and playing again with Francis, and we have resurrected Un Drame Musical Instantané, which I had dissolved in 2008, five years before Bernard’s death. Bernard had already retired from the scene in 2000. The CD ‘Plumes et poils,’ recorded with the writer Dominique Meens, was released in 2022, and Francis and I are preparing a new album around Philip K. Dick for 2024.

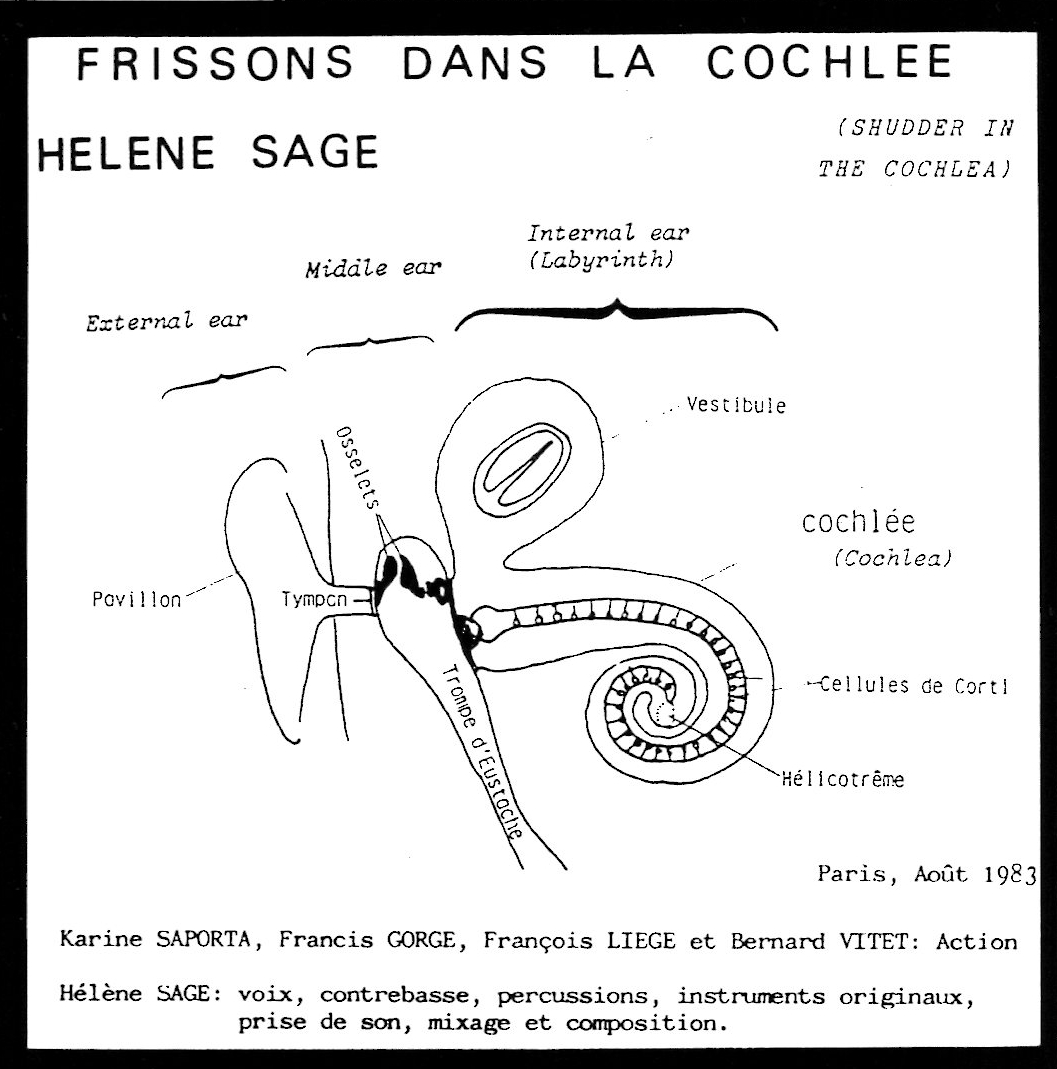

Hélène Sage discusses the history of the creation of ‘Frissons dans la Cochlée’.

In the early 80s, I lived in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, near Bercy. I enjoyed strolling by and recording in its vast underground warehouses, comprised of long bays with high stone vaults, through which trains could pass. There was an incredible natural reverberation chamber there. I used to bring my friends—dancers and musicians—to create “sound scenarios”: running, breathing, screaming, and producing sound effects using whatever materials were available—sheet metal, scrap metal, chain ends, and other miscellaneous objects—everything was fair game for enriching these sound adventures. The unexpected, such as the passing of a train or a moped, was also incorporated into our recordings.

At home, I recorded my double bass, bass flute, and various other instruments, including some of my own creation, such as the stool (a kind of Chinese violin) or the perkhydreole (a percussion instrument utilizing water and wind). Additionally, I enjoyed experimenting with early effects boxes, such as the “echotron,” for repeating and transforming voices and other sounds.

Moreover, I carried a small tape recorder with me at all times, gradually amassing an impressive original sound library, which I also drew upon (including recordings of the demolition of a wall, the creaking of building machinery, belly noises, etc.).

The mixing process was quite an adventure as well. I operated with several tape recorders, and everything had to be done ‘live’, in one take, to minimize hissing. Thus, I created giant colorful scores, detailing the timing of each sound and all necessary adjustments.

“I enjoyed imagining the hair cells lining our cochlea trembling with both fear and pleasure”

The inspiration for the title came from an old school chart depicting the inner workings of an ear. I enjoyed imagining the hair cells lining our cochlea trembling with both fear and pleasure as listeners experienced this piece.

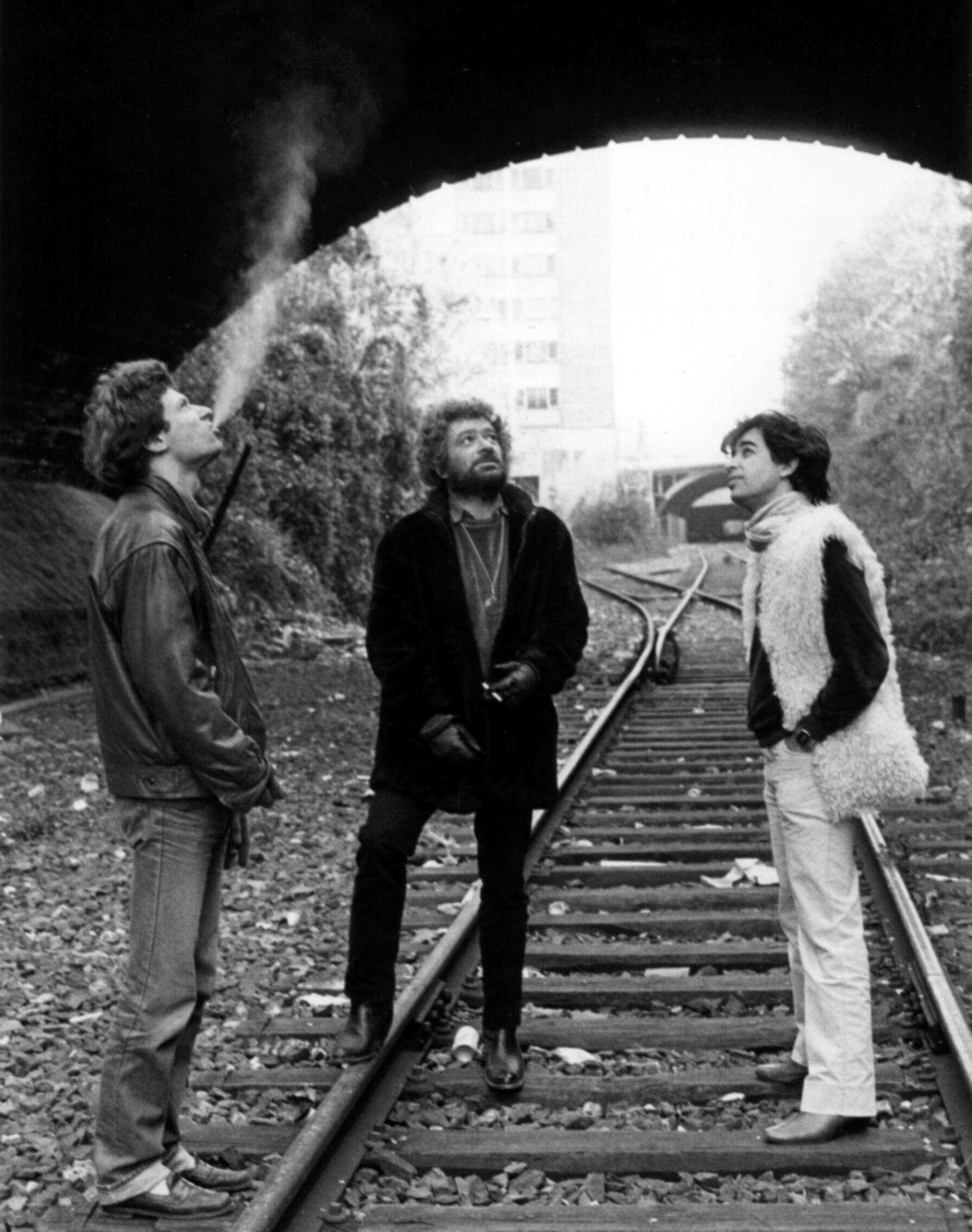

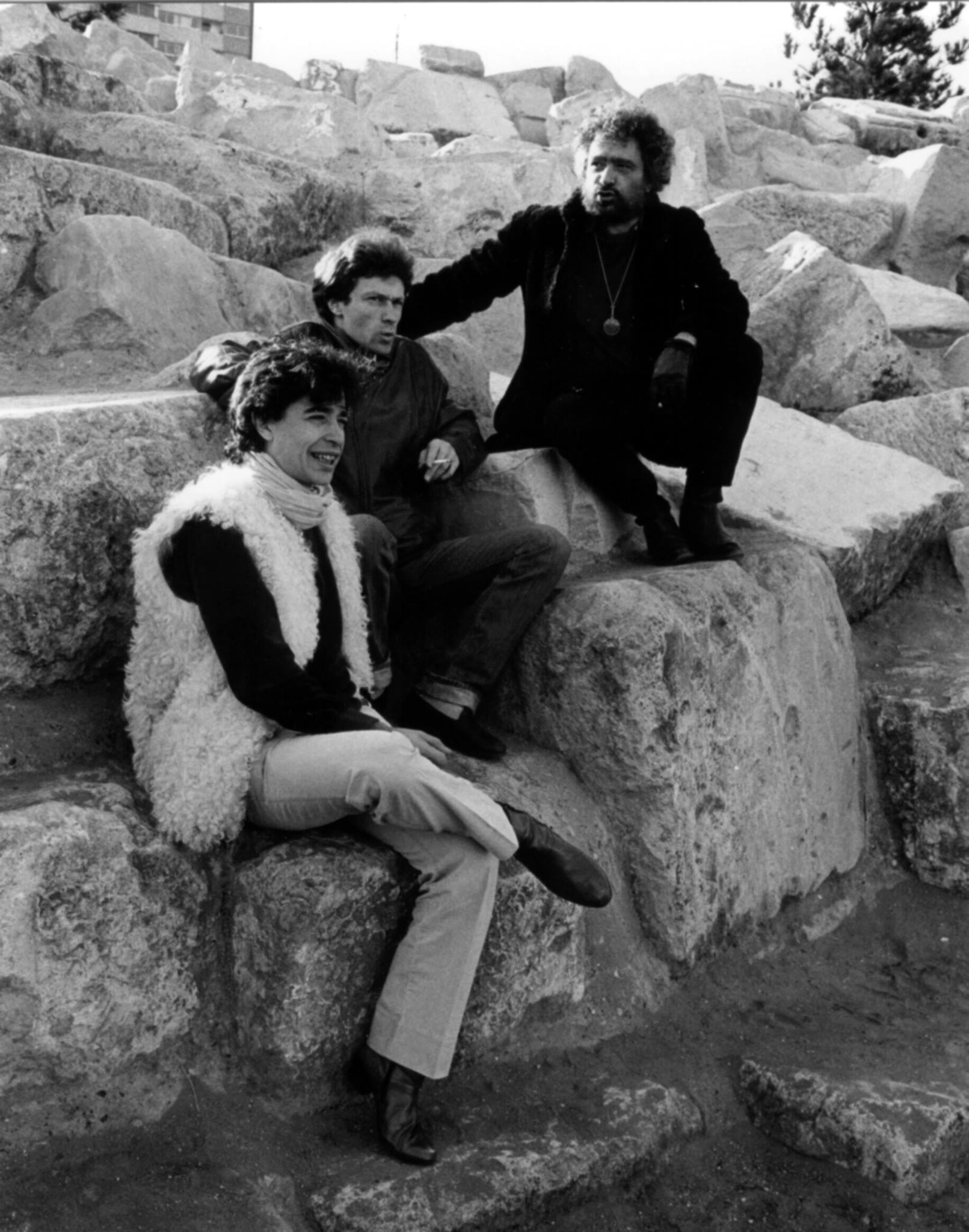

Headline photo: Un Drame Musical Instantané (Gorgé, Vitetm Birgé), under a tunnel of the Petite Ceinture, Paris, 1983 | © Marie-Jésus Diaz

Jean-Jacques Birgé and GRRR Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube / DailyMotion / Vimeo

Souffle Continu Records Official Website / Facebook / Twitter / Bandcamp

Jean-Jacques Birgé | Interview | “My imagination seems to have no limit”