René Lussier | Interview | “I follow my instinct”

René Lussier is a highly acclaimed Canadian musician known for his innovative and diverse contributions to the world of music.

His extensive discography showcases his versatility and creativity, spanning across various genres including avant-garde, experimental, jazz, and folk. Lussier’s collaborations with prominent artists such as Fred Frith, Jean Derome, and Martin Tétreault have further solidified his reputation as a pioneering figure in the Canadian music scene. His distinct guitar style, influenced by a wide range of musicians including Hendrix, Django Reinhardt, and Bill Frisell, sets him apart as a unique and influential guitarist. With a career spanning several decades, René Lussier continues to push boundaries and inspire audiences worldwide with his fearless exploration of sound.

“I follow my instinct, my pleasure, the excitement that comes with hard work”

It’s really wonderful to have you. You were born in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

René Lussier: I was born in Montreal in 1957, on the Plateau Mont-Royal, a working-class neighborhood that has gradually gentrified since. At the age of 8, my family moved to the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in the town of Chambly, in a brand-new neighborhood surrounded by mud, fields, and small woods. I attended elementary school in Chambly from the middle of 2nd grade until 7th, and then I completed my high school education from 8th to 12th grade in the city of St-Hubert. Long, numbing bus rides morning and evening. A huge school, two thousand students, I was completely demotivated and lost there.

Was there a moment when you knew you wanted to become a guitarist?

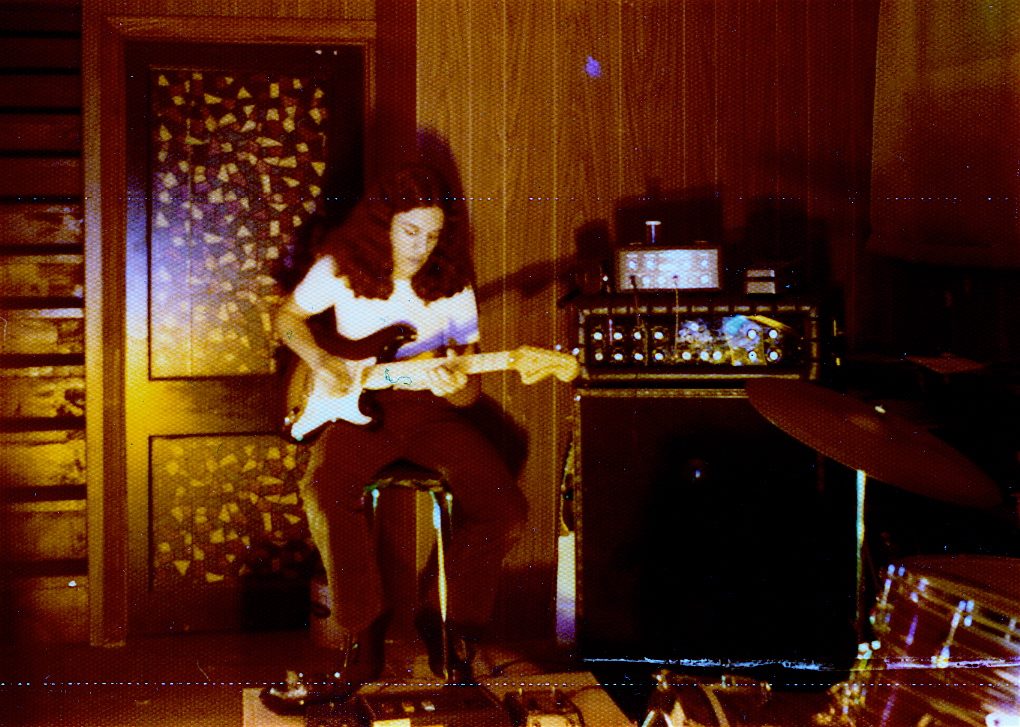

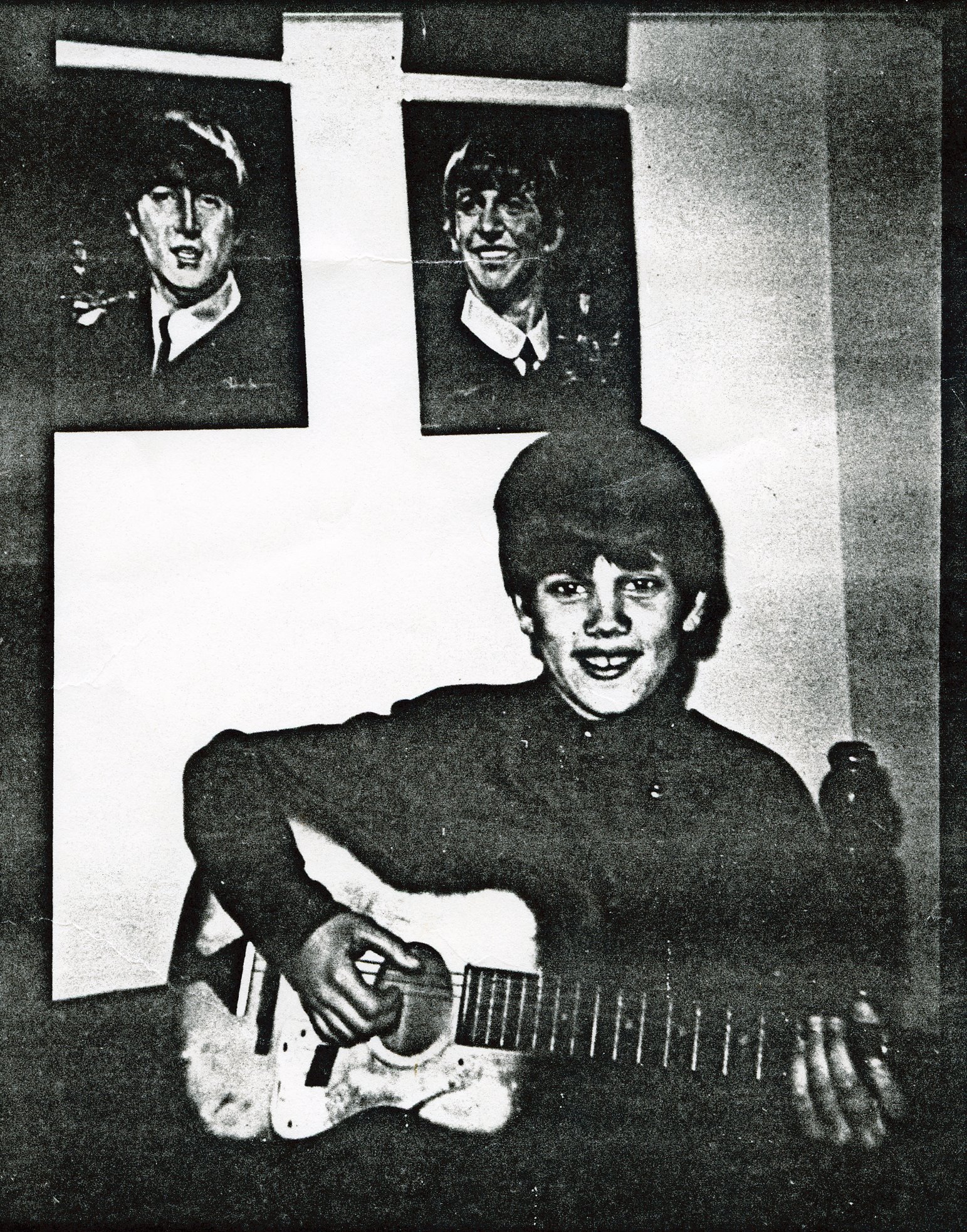

My uncle François played guitar in the band Les Black Diamond, which performed in dance halls. He still lived with my grandfather. One Sunday, I entered his small room, right next to the kitchen, and I saw, lying on his little single bed, nestled in its open case lined with orange velvet, a Fender Stratocaster electric guitar in sunburst color!

I didn’t even think about touching it, but I started dreaming of having an electric guitar and one day playing in a band. I was very excited by all the musicians I saw and heard on television. At Christmas when I was eleven, my brother and I received electric guitar and bass ordered from a very low-quality catalog. At first, we didn’t even have an amplifier. It went plingplingpling… But my father bought my uncle’s old Ampeg amp, and we started getting blisters on our fingers without having any musical foundation. I was supposed to play bass and my brother the guitar, but we quickly swapped instruments, and in that little bungalow where I spent all my adolescence, we imitated three-chord blues and rehearsed in the basement every weekend with a friend who played drums, pretending that one day we would play like pros.

Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

Yes! In my teenage years, I went to a lot of rock concerts, and then European prog music bands of all kinds, both good and not so good. American bands too, I went to see everything, rock, blues, and later on jazz.

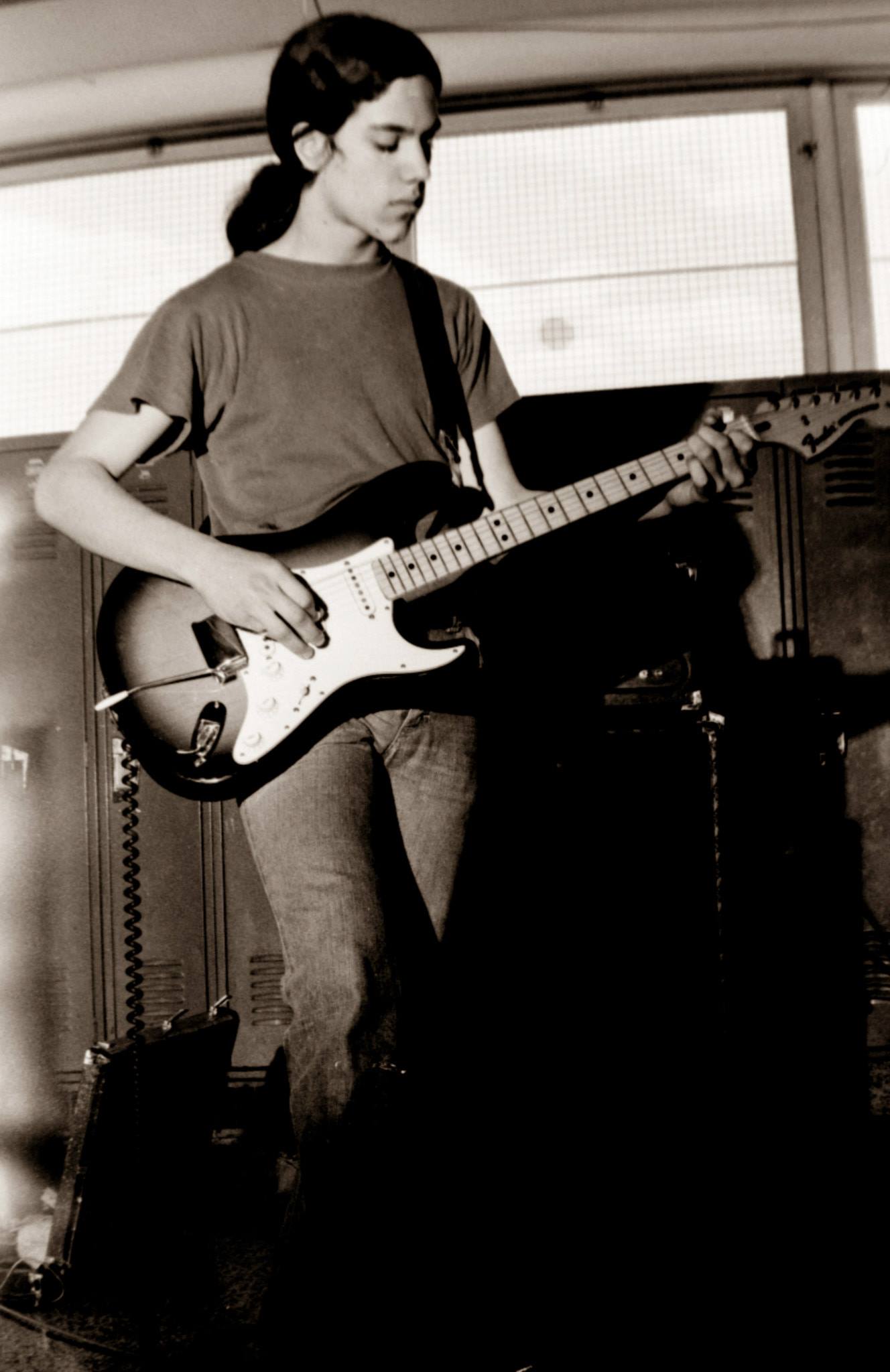

One of the first bands you were part of was called Arpège. What kind of progressive rock band was this?

Arpège was an electric quartet centered around my brother and me. A new drummer had joined us, as well as a violinist with whom we started composing under a strong influence of King Crimson and the excellent bands we saw at the time, which always showed us how much we had to improve to reach their level. We played instrumental prog rock, both highly composed and somewhat naive. Later on, the violin was replaced by the flute and alto saxophone of Gilles Gobeil, a friend with whom I still collaborate today, a remarkable and renowned composer of electroacoustic music. I was the main composer, but Gilles, who also wrote some music, handled the arrangements. We rehearsed extensively and learned absolutely everything by heart. After two years of dedication, Arpège played its first paying concert ($2 per ticket) at the Chambly cinema in December 1974. I was 17 years old.

What were you influenced by?

Through all the records we listened to: Hendrix, Crimson, Zappa, Gentle Giant, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Johnny Winter, B.B. King, Roland Kirk, to name just a few.

I still didn’t know how to read or write music, so everything was learned by heart, all crooked and passionate. It was the discovery of my creativity and my instrument. At that age and even now, music is a true refuge, a bottomless well of sensations and explorations.

Did you do a lot of shows?

Arpège played irregularly for 3 years and sometimes, as was still possible at the time, 4-5 nights in a row at various clubs in Old Montreal. All the material was original.

Was there a certain scene you were part of, maybe you had some favorite hangout places?

At the beginning, living outside of Montreal made it difficult, but from 1975 onwards, I started going there more and more often and frequenting La Grande Passe, a community bar where there were Tuesday nights of improvised music, and also Le Centre d’Essais Le Conventum, which was a hub for underground artists. That’s where I met most of the musicians I played with later on.

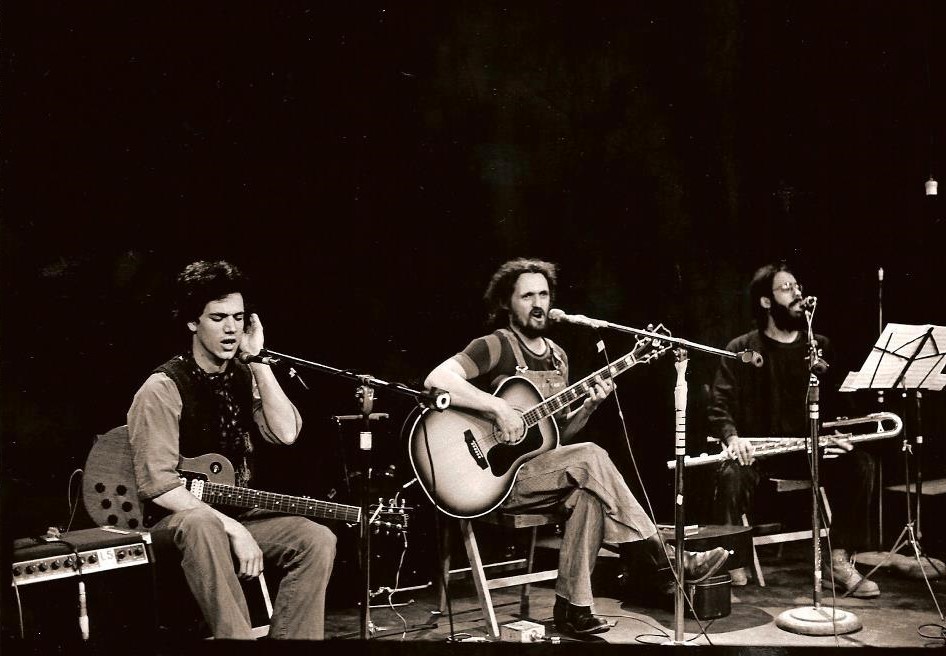

By 1976 you were playing with Montreal folk-progressive group Conventum led by André Duchesne. What kind of experience was that for you?

The encounter with André Duchesne was decisive. I dissolved the Arpège group and moved to Montreal. I came from a broken family, I had less and less contact with my parents. Conventum became my family. I was the newcomer in the new lineup, very impressed by the group and eager to prove myself. They were very demanding; everyone had to come up with original ideas, and any cliché was denounced. At first, it was very restrictive for me. Lots of rehearsals, a process where everyone found their own path, a true collective composition led by André Duchesne and also by Jean-Pierre Bouchard at the very beginning.

For 4 years, my life revolved around the Centre d’Essai le Conventum: a place of cultural effervescence that welcomed new music, poetry, folklore, dance, theater, in short, everything that the bubbling margins offered. My first film scores were co-signed with the Conventum group and André Duchesne as early as 1977. We played quite often in Montreal and in the region. Two tours in Europe in 1977 and 1979.

Would love to hear about the album making of ‘À l’affût d’un complot’ and ‘Le bureau central des utopies’. What was the overall vision in the band?

The first album, ‘À l’affût d’un complot,’ in 1977, was recorded in a luxurious studio under the Tamanoir label, a label that mainly dealt with traditional folk music. So, we were the weirdos of the stable. We recorded all together, and depending on the tracks, we had many guests to enrich a primarily acoustic orchestration. A fantastic studio experience. That’s pretty much where I discovered that the studio was a musical instrument in itself.

‘The Central Bureau of Utopias’ is an independent production that was released on the Cadence label, a self-production managed by the musicians. The album was recorded in a mobile studio in the countryside, a 16-track setup in a truck. At that time, we were a quartet. JP Bouchard had returned to his Saguenay homeland, and the poet Artur Painchaud had left us. The quartet consisted of Duchesne, Cormier, Laurin, and Lussier. It was complex, lively, and carefully crafted music. A kind of imaginary folklore.

Both of these albums fell victim to bankruptcies. They still sold well, especially the first one, but we never saw a penny from them.

How did your work with Duchesne come about? The result was Tanobe.

“Tanobé” (1979) is a documentary film score by the National Film Board (NFB) about the painter Miyuki Tanobe, a figurative artist who painted the Plateau Mont-Royal and Mile End neighborhoods of Montreal – the areas where I was born and lived. Duchesne and Conventum had already composed several film scores, but in this case, André and I co-composed it.

How did Quatour de l’Emmieux and les Reins, Nébu and La G.U.M in the late 1970s and early 1980s come about? Would love it if you could comment about each of the projects.

In parallel with Conventum, I started playing with Pierre Saint-Jacques, a very inspired pianist, improviser, and jazz composer. We formed a duo that later became known as “Les reins solides” and regularly performed in cafes and bars. Then, as a quartet with L’Emmieux. In French, the word ’empire’ closely resembles the verb ’empirer,’ which means ‘to get worse and worse’ or ‘to deteriorate.’ Conversely, ’emmieux’ is an invented word derived from ‘meilleur,’ which means ‘better. Pierre St-Jacques mainly composed the pieces. The musicians were St-Jacques, Lussier, Laurin (bassist from Conventum), and Mathieu Léger (who was the drummer of Conventum’s previous lineup). We played a fusion of jazz/rock/free.

I wasn’t in the group Nébu, a trio composed of St-Jacques (piano), Jean Derome (flute), and Claude Simard (double bass). I was orbiting around them. I collaborated on the production of the first album and played a few pieces as a guest on the second one. It was a jazz composition (ECM-style, but wilder), lyrical, spacey, and free.

During those years, I also started playing with Jean Derome, with whom I had collaborated on a multitude of projects including La G.U.M, a big band playing compositions by its members. Musicians from various backgrounds were involved: Nébu, Conventum, Pouet-Pouet band, Plancton, etc. Compositions, free jazz, humor, rock, etc.

At the time your solo career started as well. What’s the story behind ‘Fin du travail (version 1)’?

End of work, an independent production spread over 3 years because I didn’t have any money. Recorded in several studios, on various supports, according to the available deals, sometimes at night or on weekends in an NFB (National Film Board) studio where I had an accomplice. It’s an orchestral album inspired by the music for film that I was discovering at that time, with the complicity of musician friends, including Jean Derome, who supported me in this ambitious production.

Tell us about the collaboration you did with Robert Lepage.

I met Robert Marcel Lepage in 1982, and right away, it was very stimulating. We performed improvised music shows as a duo in galleries, bookstores, and cafes. Robert is a master of improvisation, a conceptual artist. He invited me to play music stemming from playful modes of play. A very contemporary approach. Another decisive encounter and a lively friendship to this day. In 1984, we both founded the Ambiances Magnétiques label with the release of our album, ‘Chants et danses du monde inanimé,’ the label’s first. AM 001. In the catalog, because ‘Fin du travail’ had been done the previous year, we integrated it as AM000.

It would be great if you could tell how you and your friends established Ambiances Magnétiques label and what was the concept behind it?

Initially, with Robert, the idea was to create a label that would become a home for all our productions and those of our friends at the time. That’s how 002 became Duchesne’s ‘Le Temps des Bombes,’ 003 and 004 a double album by Conventum bringing together our two orphaned albums. Others gradually joined in the rhythm of productions. Yet another family of musicians who were very dear to me. Seventeen years of my life. Dozens of productions and collaborations. Due to fundamental differences, I permanently withdrew from the company in 2000.

What about with Derome?

I had the opportunity to play with Jean Derome from 1978 until 2000. He is an exceptional musician, talented composer, arranger, and improviser. We collaborated for several years on film scores, multiple albums, concerts with our duo Les Granules, tours, and memorable trips with a bunch of bands of varying configurations. Our fruitful collaboration ended definitively in 2000. This immense loss of friendship precipitated my departure from the label I had founded with Robert Marcel and on which I had realized and produced so many albums.

Where does your love for film come about?

I’m not a cinephile. My love for music for film came from what I discovered while attending post-production. What impressed me the most, attracted me, transformed me, was the editing room and the collegiality among the film crew. The synchronicity between the image, the sound, and the meaning. The process, which was complex at the time because it was analog. The time it took to see the work appear. The delays imposed by the technology of that time, the mechanics of manual editing, the sorting of reels, each choice requiring time. Between action and result, time to dream. I became attached to these rituals. I did a lot of tape editing on my Revox B77 for my albums, but also for others’. I retained these reflexes even though new technologies and editing tools offer instantaneity.

What are some scores you co-written and are the most proud of?

I co-composed until 1990, but from then on, I signed all of my film music alone. I am proud of all the documentaries, all the animated films. If I have to name a few: The music for “Le Moulin à Images,” an architectural projection in the port of Quebec City on which I worked from 2006 and which was broadcasted from 2008 to 2012 with changes every two years. Millions of spectators in the old town and on the docks. Also, the music for the film “Le Trésor Archange,” about the Treasure of the Language, that of “Chants et danses du monde Inanimé: le Métro,” and that of “Chronique d’un génocide annoncé.”

How did you meet Pauline Julien? You played with her between 1982 and 1984.

Her pianist, Bernard Buisson, asked me to join the orchestra that accompanied her on tour. Pauline Julien is an icon of Quebecois song. A true passionate advocate who carried the torch for the dream of a sovereign Quebec and left her mark on her time. Surprisingly, I played a bit of guitar, but mostly drums. Several concerts in Quebec and five tours in French-speaking Europe. A fantastic experience. After all those years of instrumental music, this cabaret-style performance: every night, 25 songs. It’s the singer who leads, who is in front. The orchestra follows and must support her.

What led you to join in 1987 Duchesne’s Les 4 Guitaristes de l’Apocalypso-Bar?

I had played for a long time with André Duchesne in Conventum and for his song project “Le temps des bombes” when he asked me to join his electric guitar quartet, I gladly accepted.

Do you feel that each of your albums has a concept behind it?

I’m not a conceptual artist. I’m self-taught. I follow my instinct, my pleasure, the excitement that comes with hard work. Step by step, the concept appears when everything is finished.

‘Le trésor de la langue’ is another stunning release.

As for the parallel: both works took me several years to complete. Many trials and errors in both cases. Two projects with a cinematic spirit that transformed me.

Would love it if you could share some further words about the making of ‘Le corps de l’ouvrage’, ‘Le Tour du Bloc (w/ Now Orchestra)’, ‘Trois histoires’…

A complex, cramped orchestral work. Due to lack of funds, I had to recreate a big band with few musicians. A never-ending multi-track studio work.

‘Le Tour du Bloc (w/ Now Orchestra)’

‘Le Tour du Bloc’ is a recording made during a residency in Vancouver. I was invited by the NOW Orchestra, a large free jazz ensemble. I went there with drummer Pierre Tanguay because I’ve always enjoyed playing with two drummers. I arrived with compositions that we rehearsed for 5 days. I brought all sorts of scores, including several excerpts from film music. I adapted the music according to the abilities of the musicians and structured collective improvisations. I directed the recordings in Vancouver and did the mixing in Montreal. Along the way, VICTO Records offered to release it.

‘Trois histoires’…

Three commissioned works.

The three compositions are constructed like cinema for the ear.

‘Les mains moites’: a piece for flute and tape.

‘Roche noire’: a piece for electric guitar and tape.

‘Art brut’: a piece that pays tribute to the creation and life of French artist Marcel Landreau.

A lot of amazing collaborations happened in the 90s, not to mention all the fantastic solo albums you did.

Yes, I had the chance to meet fantastic musicians and creators during the 90s. In addition to Frith, Lepage, Derome, I worked with Heiner Goebbels, Hans Reichel, Tom Cora, Ikue Mori, Zeena Parkins, Christoph Anders, Chris Cutler. In Quebec, valuable collaborations with poet Patrice Desbiens, turntablist Martin Tétreault, drummer Pierre Tanguay, trombonist Alain Trudel, and many others transformed me and enriched my journey.

Regarding my solo guitar albums, both are improvised. The first one is electric, the second one is acoustic.

How did you begin working with Fred Frith?

The first time I played with Fred was as a duo at FIMAV (Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville) in September 1986. The recording of the concert became the first album of the VICTO label in 1987. After that, we worked together in Christoph Anders’ band State of War, with whom we toured Europe. Later, Fred came to Montreal to work with me on “Le Trésor de la Langue.”

And you were also part of the Keep the Dog project by Frith.

Yes, I went on a few tours with Keep the Dog from ’89 to ’91. North America, Europe, the Soviet Union. We played a retrospective of Fred’s compositions. He made it into a double CD: ‘That House We Lived In.’

And how did you begin working with Fred Frith Guitar Quartet?

It happened naturally because I had already been playing with him for a few years. From 1990 to 2000, many concerts with his Quartet, regular tours across Europe. So many memories, memorable trips, enriching friendships on all levels. At first, we only played Fred’s music. Gradually, he invited us to participate by bringing in our compositions and those of other composers as well. We made a first album in 1994 – ‘Quartet’ – recorded in New York, a second one in Montreal in 1997 at the Radio-Canada studios, a third one recorded on the road in 1999, a compilation of live concerts in Europe plus a studio session in Austria.

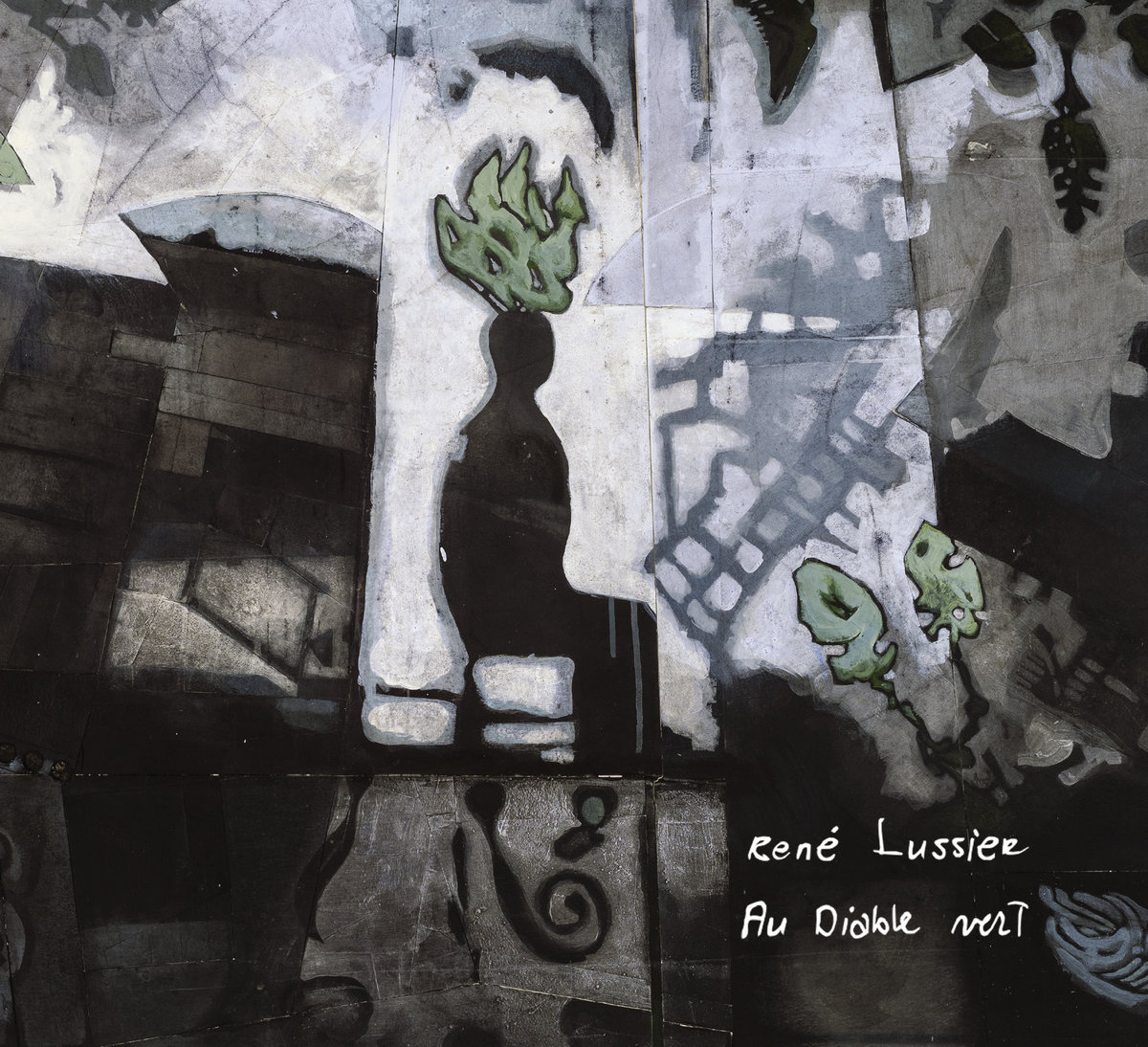

Tell us about your latest album, ‘Au diable vert’?

Before discussing ‘Au Diable Vert,’ I need to revisit the journey that led to the albums of recent years.

In 1996, I was starting to feel overwhelmed by traveling abroad and my hyperactivity in Montreal, where I was still juggling too many projects, often single-handedly. I needed to take stock and ground myself in another territory to open a new chapter of composition. I had been looking to buy a small plot in the countryside for several years, but everything was too expensive. However, that year, I managed to purchase a 10-hectare piece of land in a depressed region where prices were still ridiculously low. The house was particularly ugly but built in the heart of untouched nature, facing a fantastic landscape that never ceases to amaze me. From 1996 to 2003, I shuttled between two worlds. I continued to work with turntablist and friend Martin Tétreault – several albums in collaboration. And then, I decided to live in the countryside full-time and built a workshop where I have been composing, recording, and inviting musicians to work with me for over twenty years. I thought I owned this territory, but quickly it was the territory that owned me. I continued to make film music and record my compositions for ensembles (Tombola Rasa 2002, Grand Vent 2004, the reissue of ‘Le Trésor de la Langue’ in 2007, a 3-CD box set with 100 minutes of unreleased material). However, I was able to explore other avenues. Two albums of songs: ‘Le Prix du Bonheur’ 2005, ‘Toucher une âme’ 2013. The soundtrack of ‘Le Moulin à Image’ (2008). ‘Meuh,’ a country-swing album with a neighbor who plays lap steel guitar (2015), several concerts and collaborations with Liette Remon, a fiddler specializing in Quebec folklore. ‘Reza et moi,’ a CD of improvisations in duo with Iranian musician Reza Yazdanpanah (2018).

This abundance constantly opens up new possibilities. In 2017, I had the chance to do a project with 4 young musicians who were interested enough in my music to commit to a long-term collaboration with me. Months of rehearsals, several concerts, a tour in Japan, a first album (‘Quintette René Lussier’) in 2018. ‘Complètement Marteau’ (2021) is my first pandemic album. A compilation of unreleased pieces, all commissioned works that had never been recorded. I played all the instruments on it – except for a double bass quartet. See liner notes #4. Thinking that the pandemic was over, I started a second album for the Quintet, ‘Au Diable Vert,’ but we quickly had to distance ourselves again. Despite the difficulties encountered, this project was tremendously stimulating, nourishing, an unexpected stepping stone towards new freedoms.

I am pleased to announce that ‘Au Diable Vert’ has just won the 2024 Opus Award for Album of the Year in contemporary music.

What currently occupies your life?

Dreaming of new music. Playing guitar every day, experimenting with the daxophone, working in the studio, composing. I have a new album of original music in the works. I also have the pleasure of forming a duo with Robbie Kuster, an exceptional drummer (also a member of my quintet), with whom I’ll be going into the studio in Montreal this week. Alongside this, taking care of the place where I live and which lives within me, loving my partner Paule, with whom I’ve lived for 34 years.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

First and foremost, all the guitarists who amazed me: Hendrix, Hans Reichel, Eugene Chadbourne, Derek Bailey, Django Reinhardt, Fred Frith, Keith Rowe, André Duchesne, Bill Frisell, and many others whose music I listened to and felt they were embracing all freedoms. Their boldness gave me permission to do the same.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

I invite you to listen to my music here. And to encourage me if you wish.

Klemen Breznikar

René Lussier Bandcamp