Šumski | Interview | Kornel Šeper

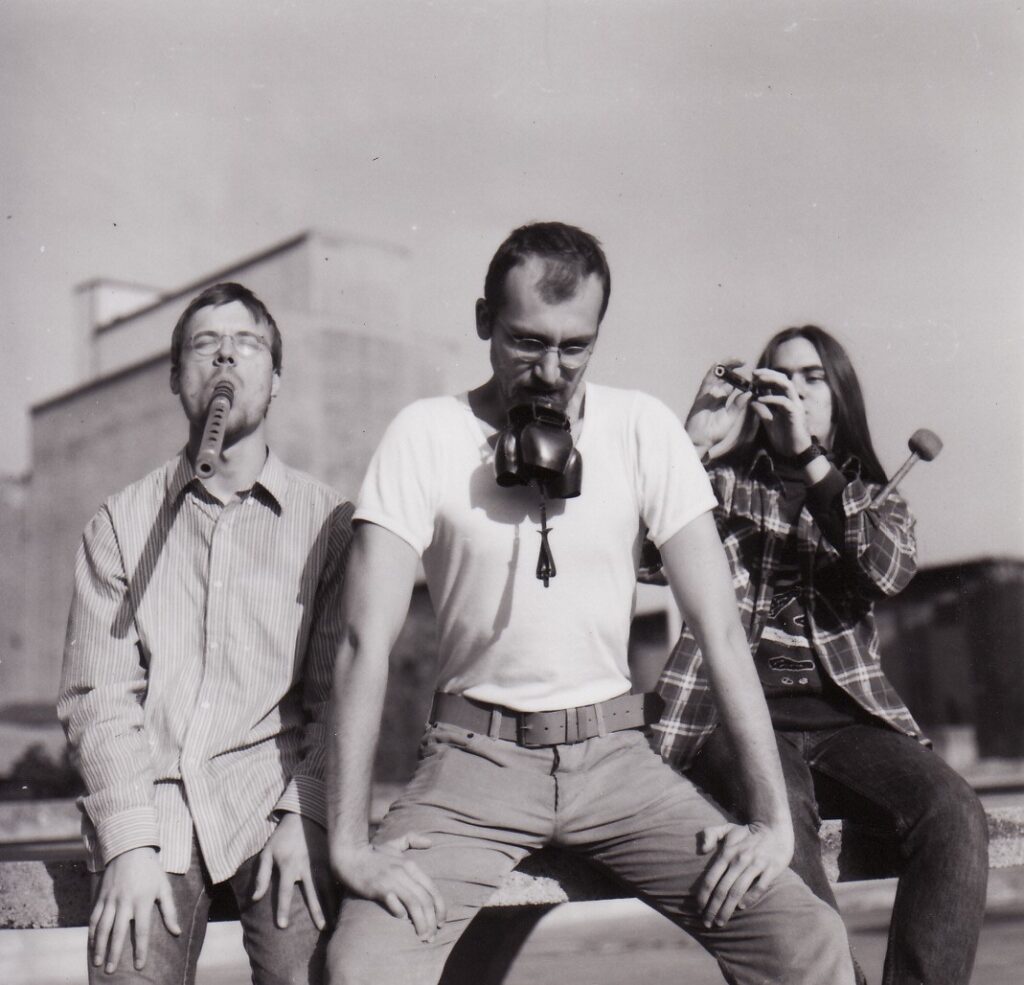

Kornel Šeper is an important figure in Zagreb’s alternative cultural landscape, serving as co-founder of Močvara club and a member of the Croatian band Šumski, which has been active for more than three decades, as well as collaborating on numerous other projects.

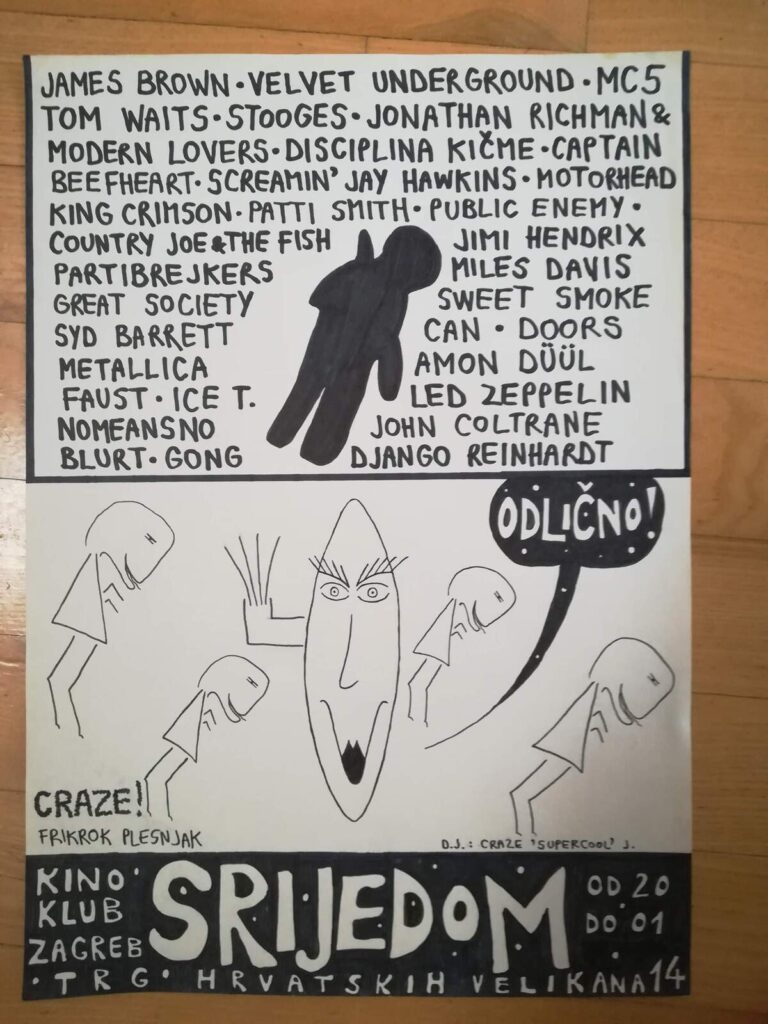

Making an enduring impact through his diverse contributions to the scene over the years, Kornel Šeper has been a defining presence. Born in 1971, he immersed himself in Zagreb’s dynamic cultural milieu, earning degrees in comparative literature and Russian language from the Faculty of Philosophy. His journey commenced in the late 1980s at the Črnomerec Youth Club, where he honed his skills as a DJ, program editor, and event organizer, laying the groundwork for his future pursuits. In 1992, Šeper co-founded the independent record label Kekere Aquarium, an underground platform that showcased seminal works by Croatian and international artists until 2000. This endeavor underscored his steadfast dedication to cultivating underground music and nurturing creative expression beyond conventional boundaries.

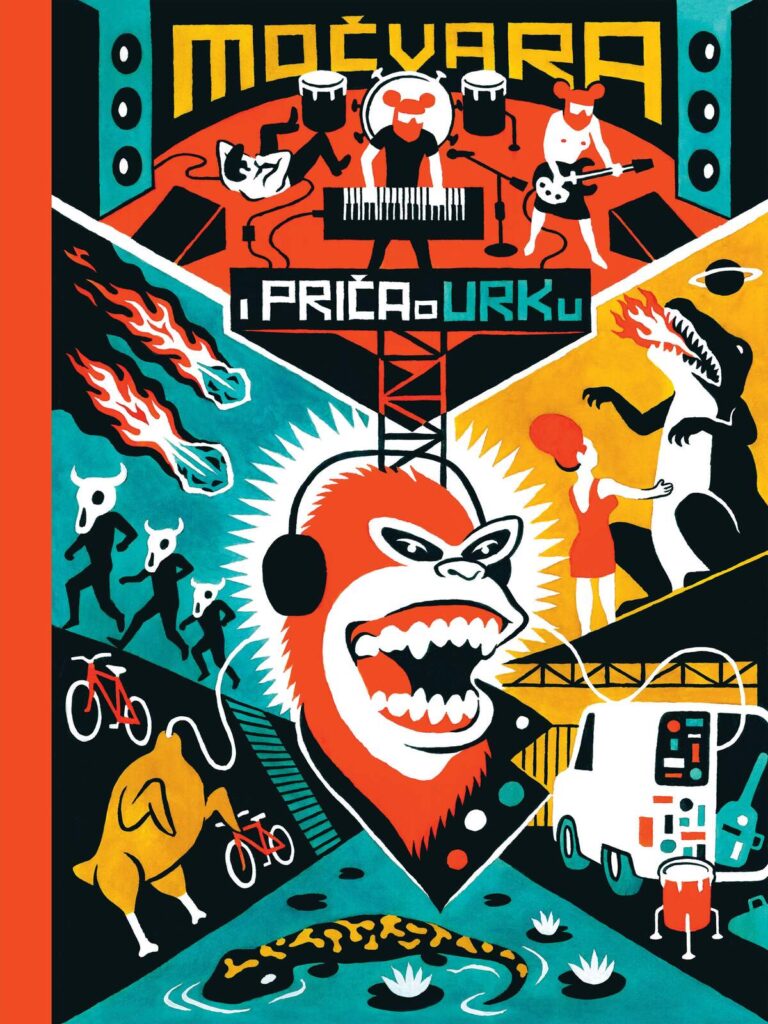

A pivotal juncture in his journey emerged with the inception of Močvara, a legendary club and cultural nucleus in Zagreb under the umbrella of the Culture Development Association “CDA” (URK). Translating to “The Swamp,” Močvara transcended mere venue status, evolving into a crucible for experimental music, avant-garde art, and progressive ideas. Šeper’s contributions encompassed a myriad of roles within URK, from financial management to curating programs and advocacy, all of which profoundly influenced the institution’s path forward.

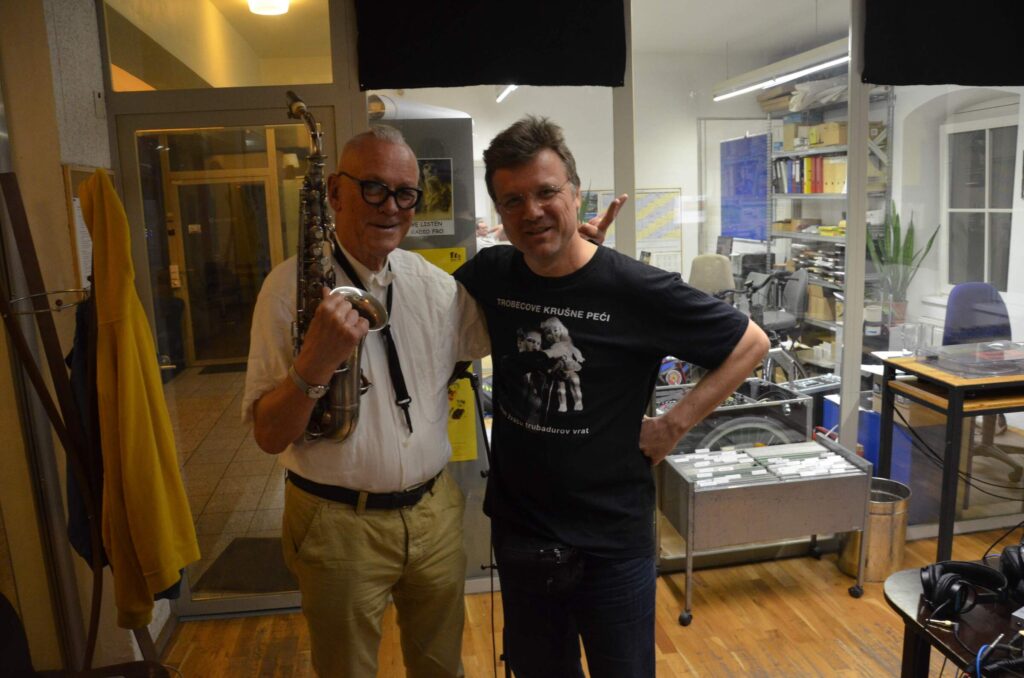

Šeper’s artistic journey extends beyond his band, as he occasionally hung out with luminaries like Damo Suzuki of Can fame, members of Amon Düül, Ted Milton etc., with whom he collaborated a few times.

His dedication extends beyond performance and production. Šeper has been instrumental in cultural advocacy, co-establishing an institution based on the model of civil–public partnership called Pogon – Zagreb Center for Independent Culture and Youth, and contributing to festivals like Ponikve and the Human Rights Film Festival. His work underscores a deep-seated belief in the transformative power of culture and community, making him a cornerstone of Zagreb’s alternative cultural landscape.

In 2018, Šeper’s commitment to documenting and celebrating Močvara’s legacy culminated in the publication of the comprehensive monograph “Močvara and the Story of URK,” cementing his role not just as a participant, but as a chronicler of a movement that continues to resonate within Croatia and beyond. The legendary club celebrated its 25th anniversary in late May 2024.

“When, after some time, I heard Amon Düül and their chaotic, unpolished music, where the collective spirit was more important than some kind of superior musical solutions, I realized that I should start from the beginning.”

Would you like to talk a bit about your background? Where did you grow up?

Kornel Šeper: My mom is from Dubrovnik and my dad is from Osijek, quite an interesting combination – the east and south of Croatia. They met at the end of the ’60s in Zagreb, where I was born in 1971. It was in a country called Yugoslavia, and now it sounds a bit strange when I write that word – Yugoslavia. On the one hand, it defined my entire childhood, but since it hasn’t existed for over 30 years, it’s faded as a concept and is often associated only with some kind of nostalgia related to numerous retro symbols and images of that time, such as Yugo cars, pioneer uniforms, or the only three types of bread that existed – white, half-and-half, and the cheapest one – brown, which people waited in lines for early in the morning. Also, it is associated with anti-fascism, but also with a totalitarian regime where you had to keep quiet about certain topics. However, compared to other communist countries, there was more freedom and information coming from the outside world. It still exists as a connected cultural space because the countries of the former Yugoslavia are close, and we speak a similar or basically the same language. Also, mutual contacts are very active, in my case in the alternative music scene.

“The Yugoslav alternative scene of the ’80s is considered by many to be one of the most interesting in the world”

How did you first get involved with music? Was there any local alternative music present where you grew up?

In elementary school, I started listening to the Beatles, then Simon & Garfunkel, and when I was about 13 years old, a turning point happened in the form of Pink Floyd. I was fascinated by them and was convinced that I had discovered some completely unknown group because no one at school had heard of them. For days, I studied the physiognomy of the four people on the cover of the ‘Ummagumma’ album, hoping to intuitively learn something about them. When I was 14, I met a psychedelic freak at a record fair who was 10 years older than me and did nothing but listen to records. He introduced me to his record collection and directed me towards bands like Brainticket, Amon Düül II, Can, Tangerine Dream, Nektar, King Crimson, and Sweet Smoke. I was fascinated by all these sounds, completely unknown to me and all my friends, and that was very important to me at the time. I decided to spread the sound to others, and already at the age of 15, in 1986, I worked as a DJ in a small club (Klub omladine Črnomerec/Youth Club Črnomerec, better known as Vrhovec), where I had my own psychedelic music listening show once a week called Korijeni priviđenja/Roots of Hallucinations (that’s how Ken Russell’s film Altered States was loosely translated here). I could play whatever I wanted, almost like playing for myself at home or for friends.

At that time, it was difficult to get hold of some important records because stores did not import records from the West. The source of the exciting sound was fanatical discophiles who traveled to Italy or Austria to get records, so those of us who did not have that opportunity would copy them on tapes or only listen to exciting descriptions and imagine what a band could sound like. The only exceptions were records from Hungary (Hungaroton) or Russia (Melodija), so I got a lot of records from the great Estonian early music group Hortus Musicus. In addition, state publishers (and there were almost no independent ones at all) released licensed foreign records, chosen by the editors of the time, on whose unfathomable approach we depended. Even though this selection bypassed many key releases, there were still some interesting examples – krautrock releases like eight Tangerine Dream albums, several Kraftwerk albums, and even two Can albums (‘Landed’ and ‘Soon Over Babaluma’). Among such more interesting releases, there was PIL’s ‘Metal Box,’ and classics such as the Doors, Pink Floyd, Deep Purple, etc., were published regularly.

The Yugoslav alternative scene of the ’80s is considered by many to be one of the most interesting in the world, so in those years I had the opportunity to listen to and see bands such as Laibach, Borghesia, Haustor, Disciplina kičme, SexA, and SCH live. Disciplina kičme was my favorite band, and I never missed a single one of their concerts. They amazed everyone with their direct message and sound – bass, drums, trumpets, minimalist lyrics with just a few lines that say it all. At the young age of 15, I was already going to concerts regularly; it was so appealing to me, so the desire to work in music was born there, from playing to organizing gigs.

Soon, I started doing other things in the club where I DJ-ed. I invited some other people to be DJs too, so very soon we had something different almost every day – from prog rock, reggae, and multicultural nights. Then I started playing movies as part of the music program, such as Buñuel’s An Andalusian Dog, Monty Python episodes, music documentaries (The Residents, Velvet Underground), and music videos. The first concert I ever organized was also there. It was for my friend Javor, with whom I later founded three bands – Šumski, Stampedo, and Zli Bubnjari.

Was there a certain moment in your life when you knew you wanted to become a musician for the rest of your life?

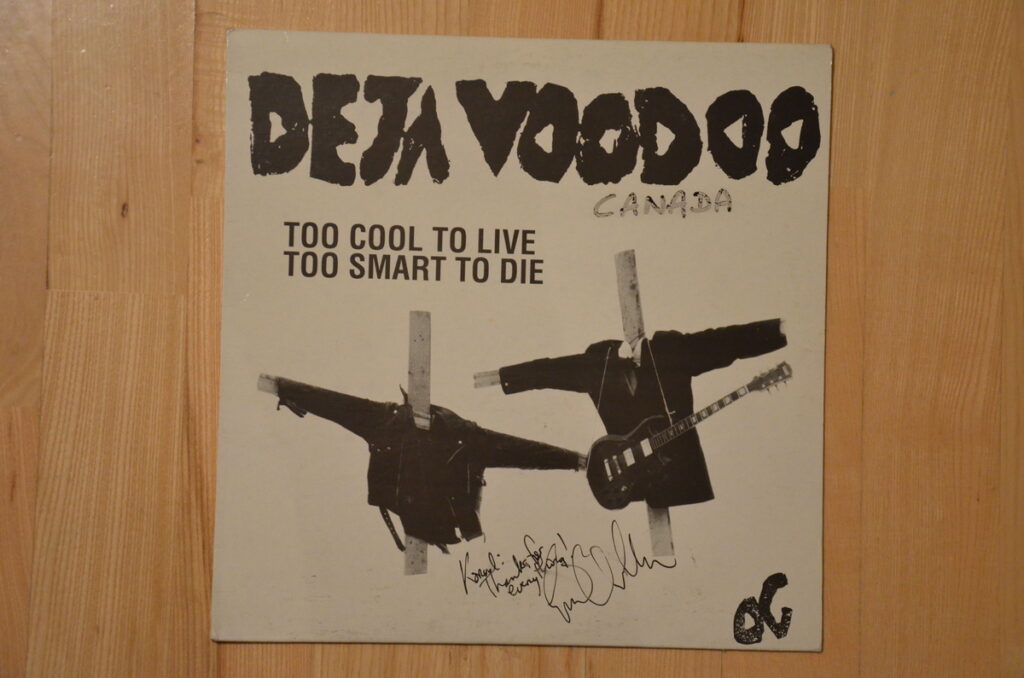

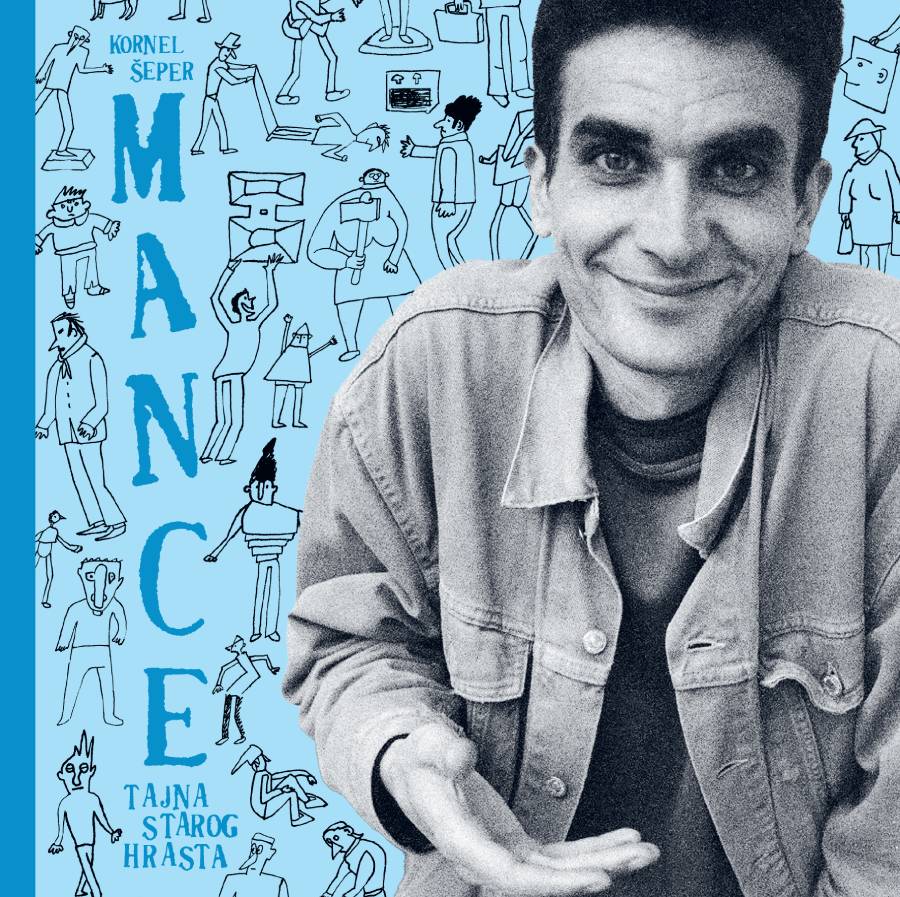

I don’t consider myself a musician; that sounds too serious to me. I just play what I can and want. I tried to play the guitar when I was 13-14 years old. I also went to a course where they taught us to play the Beatles, but I wasn’t good at it and didn’t see any point, so I gave up. When, after some time, I heard Amon Düül and their chaotic, unpolished music, where the collective spirit was more important than some kind of superior musical solutions, I realized that I should start from the beginning. This is not about the more famous band Amon Düül II, but about another band, which was sometimes called Amon Düül I, and from which Amon Düül II emerged. I had previously lent my acoustic guitar to the jazz guitarist Ivan Kapec, who gave it to his dad, and I lost track of it. Then I borrowed an acoustic, very bad guitar from a classmate, with which 10 years later Mance, the legendary Zagreb singer-songwriter, would record his first album. It turned out to be one of the most important Croatian albums, where it was not at all important how that guitar sounded, but what emotion he could take out of it. I played that guitar, forgetting all the previous lessons and only remembering how Amon Düül or the Canadian rock and roll minimalists Deja Voodoo did it.

Šumski formed more than three decades ago. Would you like to elaborate on how the original lineup got together?

I founded the band with my friends Jura and Javor in 1991, and we weren’t very good at playing at the time, but that wasn’t too important because we had a bunch of ideas. My initial idea was to play Amon Düül covers in order to introduce that band to the people in Zagreb. We rehearsed every day, recorded the rehearsals on a Walkman, and that’s how it all started. After the first few rehearsals, we immediately started working on our own music, which had nothing to do with any specific styles of music. Punk and garage rock were popular at the time, but we weren’t interested in that. I remember that we were surprised by each new song, and it was all very funny to us.

What was the mutual interest between the members? What were some of the influences you wanted to employ in your playing?

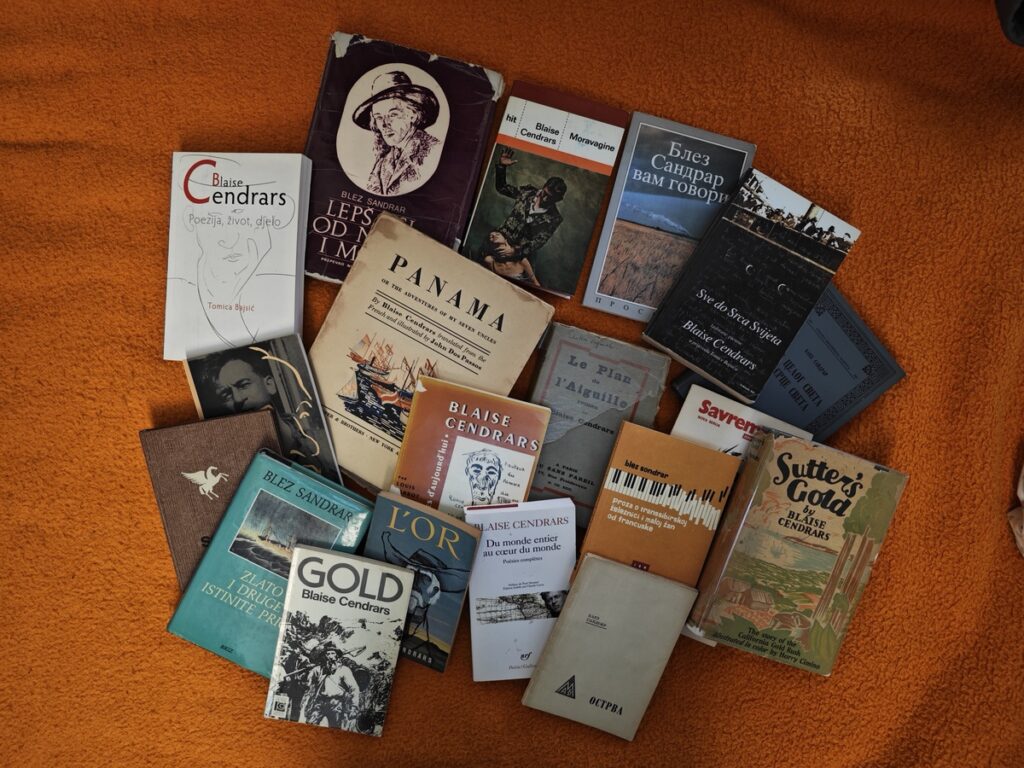

We had some non-musical influences, the most important of which were the writer Blaise Cendrars and the director Jacques Tati. We saw our music through Cendrars’ untamed writing and multicultural mentality and Tati’s naivete. We also considered crickets to be an important influence, so our early song was called ‘Cvrčak se budi’ (“The Cricket Awakens”). All in all, it didn’t look like a typical rock band, so instead of the usual rocker drink of choice – beer – we drank milk at our early shows.

We loved krautrock, especially Faust and Can. The only songs we ever covered were theirs – ‘J’ai mal aux dents’ and ‘It’s a Rainy Day, Sunshine Girl’ by Faust, and ‘Connection’ and ‘Mother Upduff’ by Can, with a couple of attempts to cover Amon Düül. The English band Blurt was one of our favorites. We loved Captain Beefheart, medieval music, various types of traditional music, and certainly Jonathan Richman, who once said that he liked our song ‘Javor.’

Was your label, Kekere Aquarium, formed with the intention to be able to release your music as freely as possible?

I didn’t intend to release our music only. Our first album was the fourth Kekere release. The impetus for establishing the label was the accidental discovery of an unreleased album by the Zagreb post-punk/neo-funk band Trobecove krušne peći, recorded in 1985, which no one wanted to release. In 1992, the band’s singer, Bega, asked me to make a cassette copy of the original tape so that he could listen to it at home. When I did it on the local radio, I was so shocked by the quality of the album that I founded the label the same day and released that album. To clarify, this label of mine (as was the case for some other colleagues) wasn’t a serious business, but actually an enthusiastic home business run from my childhood bedroom in my parents’ apartment.

But there are several other releases apart from Šumski; tell us about those.

The idea of the label was to release music that I liked and that was outside of the mainstream. There were ambient electronic music pieces for the theatre play RUR, Voodoo Buddah, the only Croatian band whose role models were Rip Rig + Panic and Don Cherry, noise bands like Why Stakla, Gone Bald, Ha Det Bra, Pink Noise Quartet, Ewa Braun…, the singer-songwriter Mance, Amon Düül, and three Šumski albums.

And you actually reissued Amon Düül’s ‘Psychedelic Underground’ on tape. How did that come about? How did you get in touch with members of the band?

When I was 14-15 years old, I really loved Amon Düül II. I thought – if there’s Amon Düül II, then maybe there’s an Amon Düül I that could be good too. There was no internet, so there was no way to find out. One day, my friend Javor, with whom I shared musical and life experiences, bought Amon Düül’s record ‘Collapsing’ at a fair. We were both completely delighted, and I soon acquired ‘Disaster’ at the same fair. We considered it the most cheerful music, completely free from the shackles of all music styles, and they were ten times more radical than Amon Düül II and any other band.

It was all very mysterious to me, and I wanted to find out more. I knew that the band was from Munich, and one day around 1990, I got on a bus in the evening and arrived in Munich around 8 am. I had with me a list of the band members’ names from the cover of ‘Disaster.’ The first person whose number I found in the phone book was Ulrich Leopold, the band’s bass player. The act of flipping through that directory in the phone booth was very exciting, and I didn’t know what to expect. Ulrich answered, I explained that I was a fan of his band from Zagreb and that I would like to meet him, so he immediately invited me to his place for tea. Half an hour later, I rang the doorbell, and a nice guy opened the door, and we started hanging out. I guess that at the time, no one really showed any interest in them, so it was unusual for him that I showed up. We had some great conversations, the highlight of which was when he went down to the basement and brought out some tapes of demos and rehearsals that he had almost forgotten about. He didn’t have a tape recorder, but the next day he called his friend who had one, so we listened to it. It was a dream come true – hanging out with a member of Amon Düül and listening to their unreleased earliest recordings that hadn’t been touched for years!

After that, we corresponded and met a few more times. In 1993, when I hitchhiked aimlessly around Europe with a friend, I visited Ulrich and asked him about the fate of the other members. He mentioned that he didn’t have their contacts but knew that Helge lived in Berlin. The next day, we left for Amsterdam, but the first car we got into was going to Berlin, so we changed our plan and ended up in Berlin for the first time. I found a payphone with a phone book, and Helge’s name was there. He gladly accepted the invitation for a drink, so soon we were drinking beer in a bar in Kreutzberg. And that’s how a long-lasting friendship was born. After some time, the band members reconnected, and it’s possible that it happened partly because of me. Both of them visited Rainer and Ella Bauer in Vienna, whom I also met later. Helge and Ulrich recently visited me in Zagreb, and we even jammed a bit. Helge was also in Vis 20 years ago, where he attended a workshop of my group Zli bubnjari, which was created under the direct influence of his band.

In 1998, I suggested that I release some of their stuff for Kekere, and we agreed on ‘Psychedelic Underground,’ which ended up being one of the best things I’ve done in my life, even though it was only a 100 cassette edition. I remember that at that time I had very little money, and I mailed those tapes to the band members when Šumski was on tour in Germany because it was much cheaper than sending them from Zagreb.

Did the lineup of Šumski change during all the years of being active?

Yes, the lineup changed over time. The original lineup consisted of Jura, Javor, and me, along with various drummers who took turns. After a year, Javor left, leaving Jura and me as the only original members. Around 2000, we found our drummer Viktor through an ad, and since then, the three of us have been the core of the band. We often had guests on albums who occasionally appeared as extras at our gigs. However, from 2018, the lineup started to expand rapidly, and we introduced trumpet, cello, mini moog, sampler, saxophone, and a second guitar.

Would you like to take us down memory lane and share as much as you remember from writing, releasing, and producing your albums?

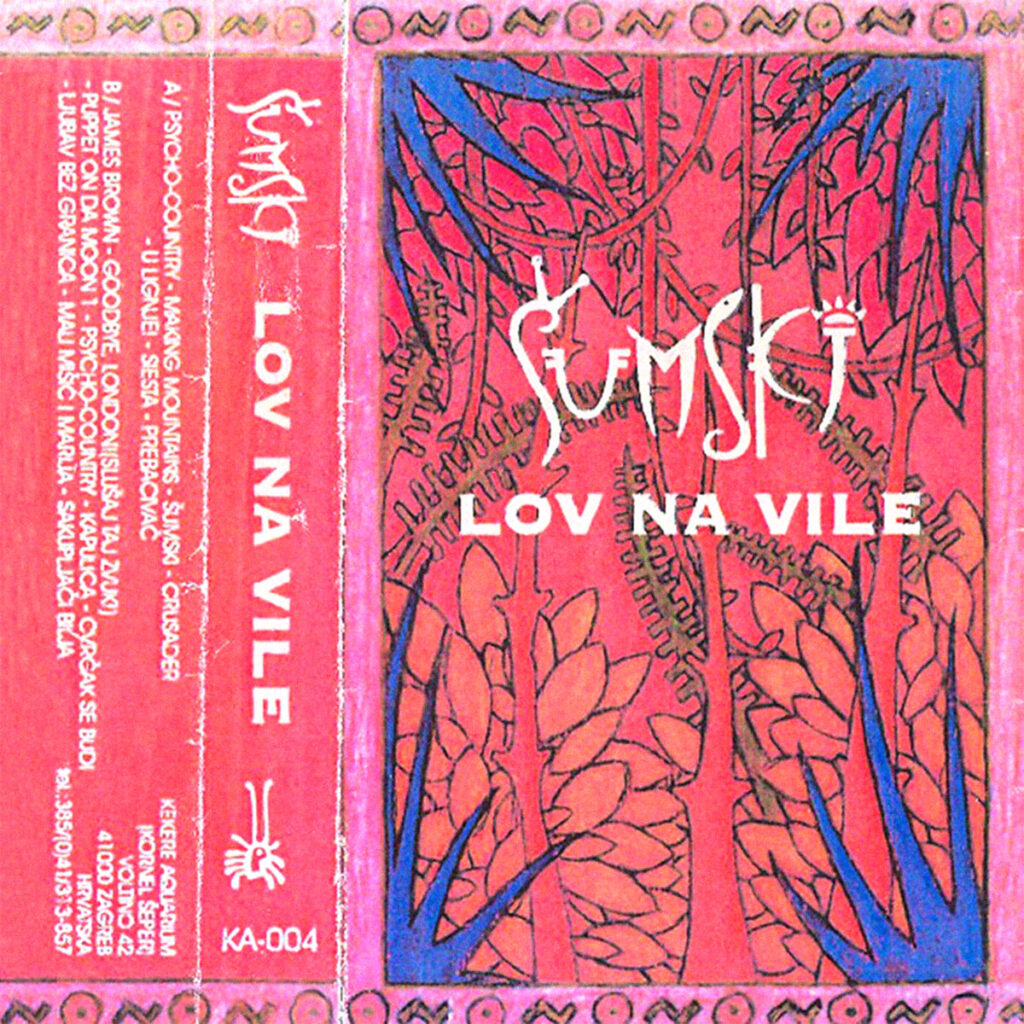

‘Lov na vile’ (1993):

It’s a compilation of recordings from 1991-1993. Most of them were recorded with a Sony WMD3 Walkman during rehearsals or in apartments, with a few attempts in studios. Lacking funds for a studio, we improvised by recording additional channels through two tape recorders. Genre-wise, it’s completely unrelated to anything and reflects our exploration of what our band could be. We didn’t really know how to play, but every note played was a great joy, and you can feel it. It is certainly one of my favorite albums of ours.

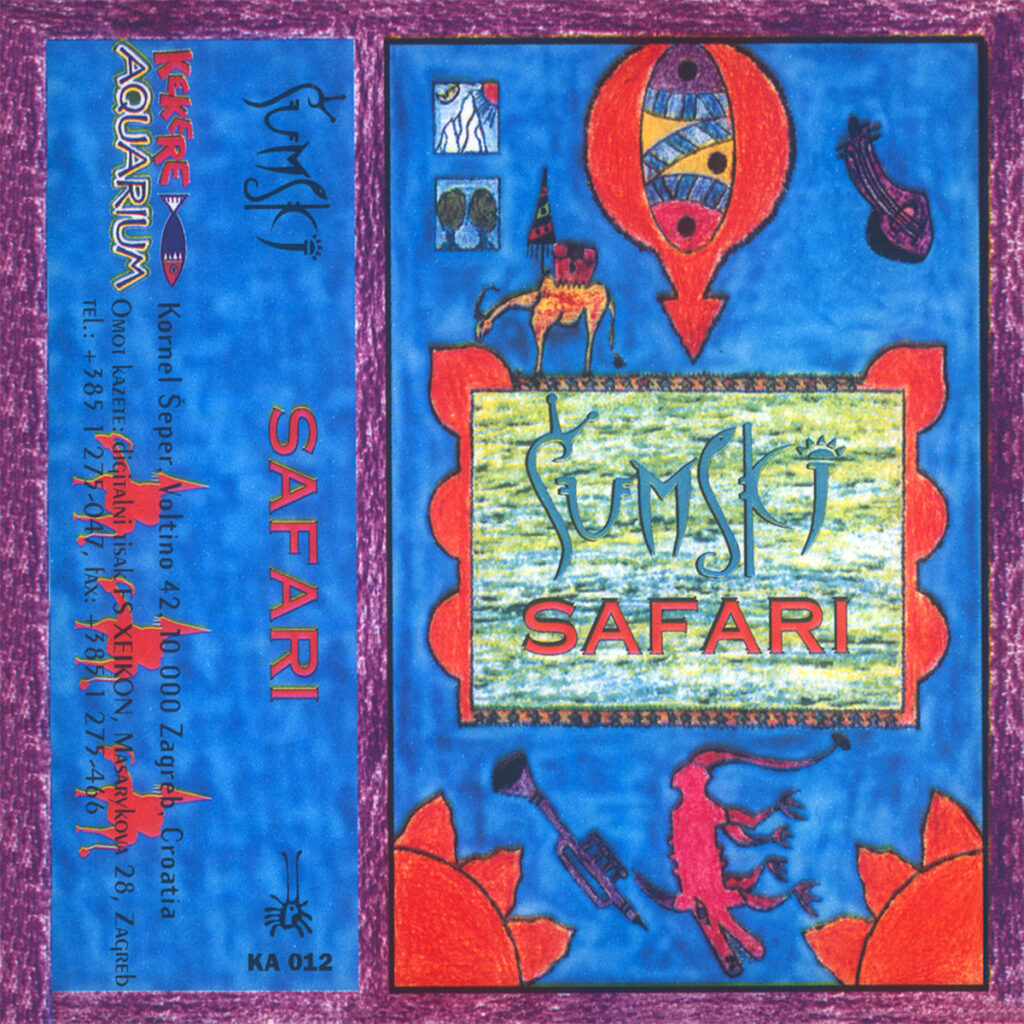

‘Safari’ (1995):

Here, we had structured our sound a bit more and improved our playing. The album features noise tracks (‘Mali mišić i Marija,’ ‘Fish Mafia’), ethno influences (‘Laguna’), naive sounds (‘Jacques Tati ide na more,’ ‘3 kućice’), partisan themes (‘Partizani’), and journeys through exotic regions (‘Safari’).

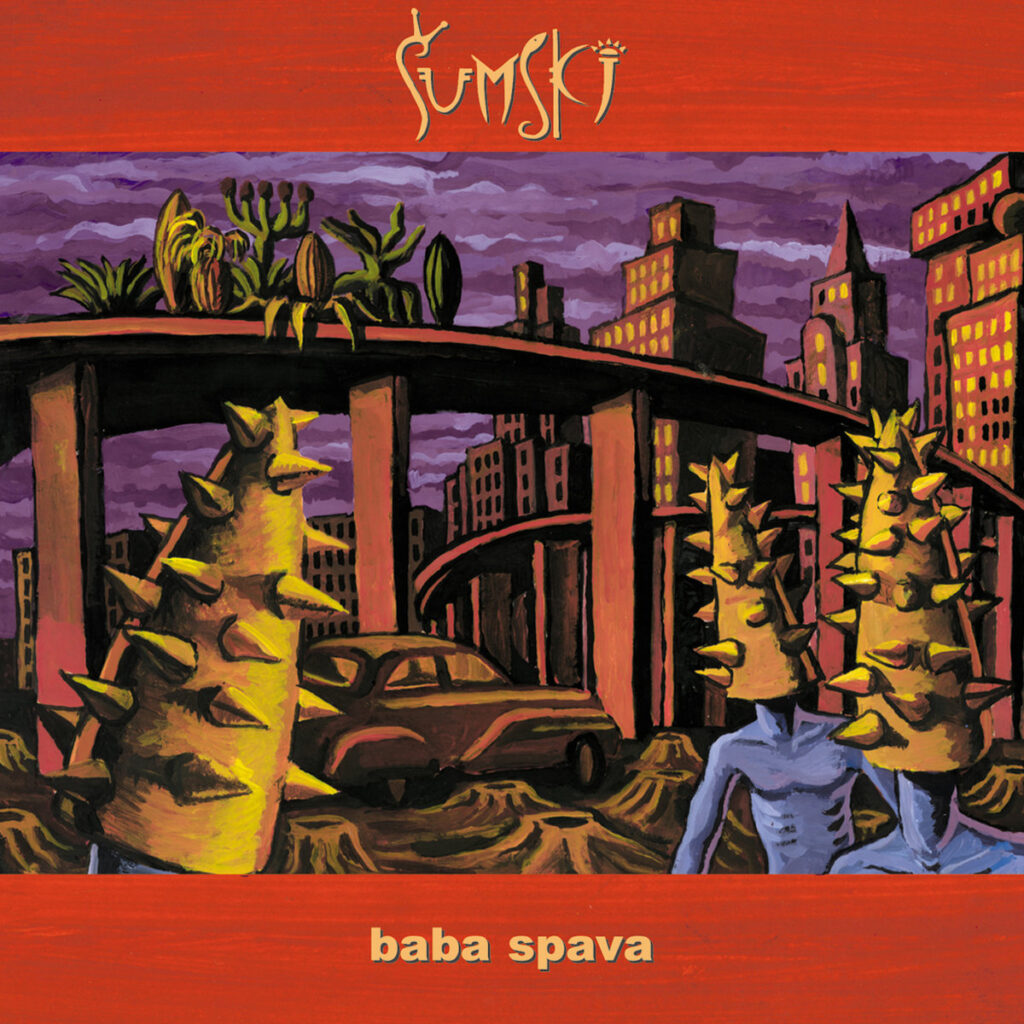

‘Baba spava’ (1999):

This album includes songs created from 1991-1999, some of which were previously recorded (‘Partizani,’ ‘Safari,’ ‘James Brown’). Unlike the other albums, it was entirely sung in Croatian, a trend continued in subsequent albums. At the time, it was our most accessible album for both audiences and critics; some songs even received radio play – ‘Baba spava’ and ‘Mali sat.’ This was the first cover art done for us by Igor Hofbauer, one of Croatia’s most interesting illustrators.

‘Ronioci’ (2003):

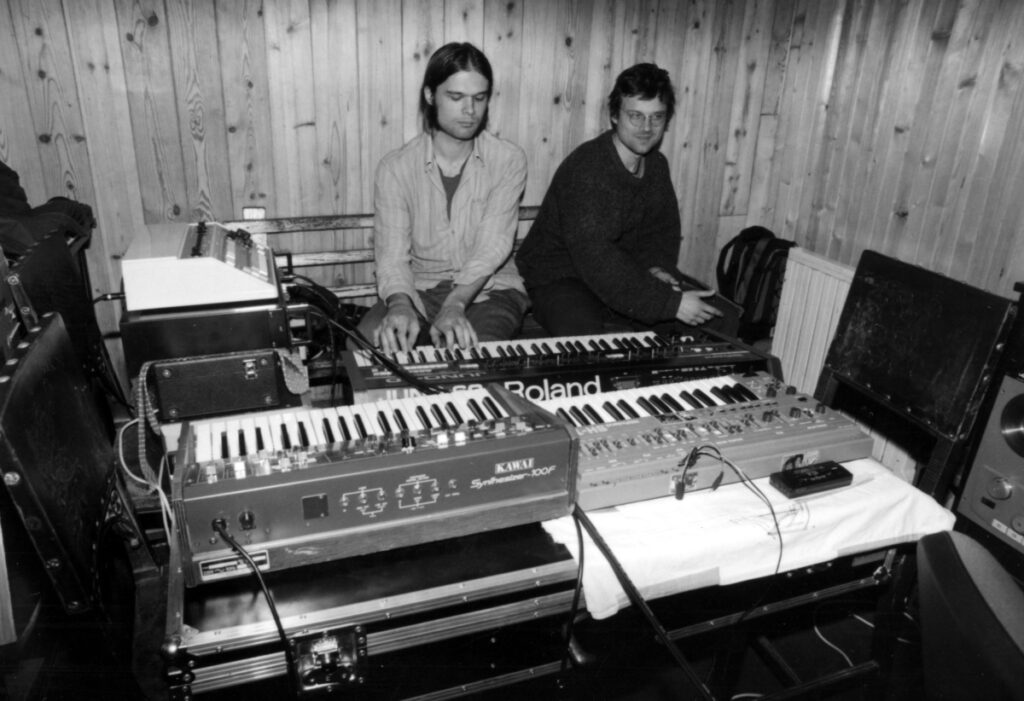

Here, a key member of the band, drummer Viktor Krasnić, appeared for the first time, alongside Croatian Conny Planck – Hrvoje Nikšić Niksho, who contributed analog synthesizers and later founded the renowned Kramasonik studio. The album cover was again created by Hof. It’s a peculiar blend of new wave, krautrock, and pop.

‘Ostrvo ledenog kita’ (2018):

After a 15-year creative break, we returned to the studio with new songs and new members. This was our first album recorded at the brilliant Sunday Studios in Sveta Nedelja with Sven Pavlović, who was captivated by our sound and soon joined the band. Ted Milton from Blurt, our hero, added his saxophone to two tracks. For the first time, we partially financed the album through a crowdfunding campaign, a rarity for bands in our country. Gerad van Herk from the fantastic Canadian band Deja Voodoo had an interesting comment about ‘Ostrvo:’ “Sounds like it would get people from a bunch of different music backgrounds to dance together.”

And you have a new album out. How long did you work on ‘Kolobari’? Would you say it’s a result of the pandemic?

We worked on ‘Kolobari’ over the span of a year, taking our time without rushing. While some of the lyrics have taken on a bit of a darker and potentially disturbing tone, touching on themes like death (as in the song ‘Smrt’ or ‘Death’), one might speculate it’s a reflection of the pandemic. However, despite this, there’s a lot of joy and zest infused throughout the album. For the first time, we incorporated the harpsichord, an instrument I’ve always admired, played by Giuseppe Ianpieri. We successfully co-financed the album through a crowdfunding campaign. ‘Kolobari’ was released by Geenger Records, Zvuk Močvare from Zagreb, Pop Depresija from Belgrade, and Trottel Records from Budapest.

Can you share further details on how your latest album was recorded?

We recorded ‘Kolobari’ at the beautiful Sunday Studios in Sveta Nedelja with Sven Pavlović. We took our time to record and mix until we were completely satisfied with the result. The musicians featured on the album include Marin Juraga (guitar, vocals, main author), Viktor Krasnić (drums), Franjo Glušac (guitar), Igor Pavlica (trumpet), Stanko Kovačić (cello), Sven Pavlović (moog, sampler), and myself on bass. We also had notable guests like Dan Kinzelman (an American saxophonist living in Italy), Giuseppe Ianpieri (an Italian metalhead with a penchant for classical music who played the harpsichord), Leo Beslać on synthesizers, and Nikola Santro on trombone. The album cover features drawings by Mance, a longtime friend. The album’s name, ‘Kolobari’, refers to circles and dark circles (such as those under your eyes), and it can be interpreted in several ways—from fatigue or a life filled with experiences that leave their mark, to natural circles like the moon or waves, or even the daily routines we break free from with this album. Jura’s evocative Zen lyrics complement this narrative.

How pleased were you with the sound of the album?

The sound is great! Recording at Sunday Studios with Sven is always a real pleasure.

What’s your creative process like? Did it change over the years? How important is improvisation for you?

Initially, we all played various instruments, and the songs mostly lacked structure or arrangements; there was a lot of improvisation. Later on, Jura emerged as the dominant songwriter. Through improvisation during rehearsals, we collectively transform his riffs into songs that you can hear on our albums and at concerts.

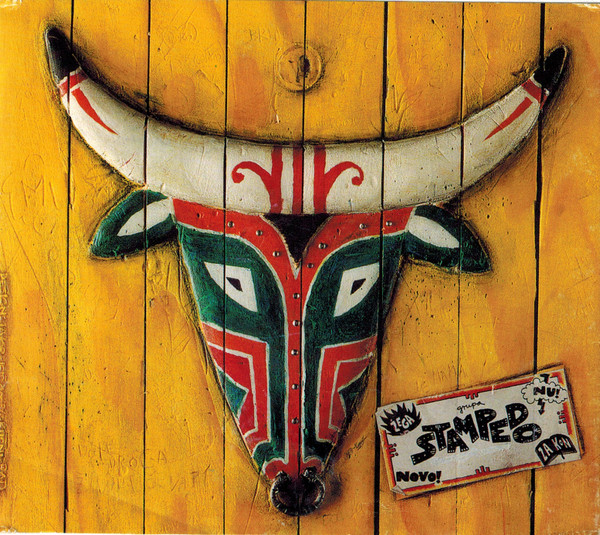

What about Stampedo?

In 1993, we found ourselves without a drummer, so during this band hiatus, we invited back an old member, Javor, to casually join us. Soon after, Javor began contributing his own songs, leading to the formation of a band initially named Kozmo. Javor had this quirky idea of creating music that his parents would appreciate, resulting in a somewhat retro and humorous sound.

Coincidentally, the band caught the attention of a commercial record label, which funded our first music video for the song ‘Stampedo.’ This track became an overnight sensation, despite its lyrics consisting of just one word—stampede. Perhaps amidst the dominance of trash pop music at the time, our sound offered something refreshingly optimistic and different. Over the years, many members have come and gone, but Stampedo continues to exist today, albeit with no original members remaining except for the vocalist, Ivanka.

Do you often play live? Who are some of your personal favorite bands that you’ve had a chance to play with over the past few years?

We don’t play live too often, as opportunities are limited. However, we were fortunate to share the stage once with our favorite crazy Estonian band, Ne Zhdali.

Another memorable experience was playing a session together with Damo Suzuki, whom I’ve been reminiscing about recently.

After a long time, we organized a tour: 15. 11. Murska Sobota, MIKK / 16.11. Budapest, Gödör club / 17.11. Brno, Kabinet Muz (with Enablers) / 18.11. Berlin, Schokoladen / 19.11. Hamburg, Elbdeich Studio / 20.11. Luxembourg, Mirador / 21.11. Dordrecht, DOOR Dordrecht / 22.11. Amsterdam, Occii (with Howrah) / 23.11. Munchen, Glockenbachwerkstatt.

What’s the local scene there like? What are some local or even national bands that you would like to recommend?

In the mid-nineties, post-rock and noise rock bands like Peach Pit, Uzrujan, Why stakla, and Ha Det Bra were trending. Today, the Croatian music scene is incredibly diverse, spanning genres such as jazz, improvisation, world music, krautrock, singer-songwriters, and more, often blending these styles. Some of the standout acts include Mimika, Seine, Nemeček, Dunjaluk, Šumovi protiv valova, Nina Romić, Bebe na vole, and Dunja Knebl. Looking beyond Croatia, notable names include 21 vek from North Macedonia, Svojat and Oholo from Slovenia, Repetitor, Lenhart Tapes, and the young hardcore band Neven from Serbia.

“I co-founded Zagreb’s underground club Močvara”

What currently occupies your life? What are some future plans?

In 2023, my second monograph was published, focusing on Mance, a genius musician and artist from Zagreb known for his outsider profile akin to Jandek, Syd Barrett, and Daniel Johnston. Despite its niche focus, this book garnered more media attention than anything else I’ve done. Currently, I’m planning the vinyl reissue of all Mance’s albums and Kekere Aquarium’s return as a co-publisher for the excellent Zagreb band Peach Pit, after many years.

I co-founded Zagreb’s underground club Močvara, operated by the non-profit organization URK, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. Močvara is a cultural hub offering not just music but also theater, workshops, literature, exhibitions, and book publications, with activities almost daily. Throughout the pandemic, Močvara remained active, hosting online programs, limited-capacity concerts, and events with closed bars, distinguishing itself as one of the few clubs in Croatia and beyond to operate continuously under all circumstances. Additionally, Močvara has co-organized the Human Rights Film Festival for over two decades.

Are any of you involved in any other bands or do you have any active side-projects going on at this point?

Apart from Stampedo, there’s also Zli bubnjari (Evil Drummers), who recently celebrated their 30th anniversary. It’s a group of ten people, each with a drum. We don’t have rehearsals or recordings; instead, we frequently perform at protests or other local events. Our communication is solely through word of mouth; we don’t use social networks. The group was founded under the direct influence of Amon Düül and their liberated approach to drumming.

In the early 90s, I had a casual project called Shine Design, which only had one concert because we mostly played for ourselves during rehearsals without any ambitions. The distinctive aspect of Shine Design was its emphasis on improvisation; at the beginning of each rehearsal, the guitarist would detune the guitar and play intuitively.

Šumski also has interesting connections with other bands. Some members have played or still play in a variety of other notable bands such as Brujači, Cul-de-Sac, Franz Kafka Ensemble, Haustor, Mance, Meduze, Peach Pit, Rujan, Sin Albert, Stampedo, Uzrujan, and Zli bubnjari.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

Of the newer ones I’ve listened to, I would single out Portron Portron Lopez’s albums, check them out. Here are some albums that I really like:

Don Cherry: ‘Brown Rise’

Disciplina kičme: ‘Sviđa mi se da ti ne bude prijatno’

Faust: ‘So Far,’ ‘Faust Tapes’

The Great Society: ‘Conspicuous Only In Its Absence,’ ‘How It Was’

Blurt: ‘Celebrating The Bespoke Of The Little Ease’

Captain Beefheart: ‘Lick My Decals off, Baby,’ ‘Spotlight Kid,’ ‘Shiny Beast’

Misty in Roots: ‘Live at Countervision’

Mance: ‘Melodije sobe i predsoblja’

Nico: ‘Marble Index’

Can: ‘Delay,’ ‘Future Days’

Amon Düül: ‘Disaster,’ ‘Psychedelic Underground,’ ‘Collapsing’

Jonathan Richman: ‘SA,’ ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll with the Modern Lovers’

Hortus Musicus: ‘Danielis Ludus’

Tangerine Dream: ‘Zeit’

John Bender: ‘I Don’t Remember Now / I Don’t Want To Talk About It’

Miles Davis: ‘Ascenseur pour l’échafaud’

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

I’m not a fan of virtuoso bassists like Jaco Pastorius. But here are a couple that are very interesting:

Mike Watt (Minutemen) and Rob Wright (Nomeansno) – both of them are heard loud and clear and have an equal role in the band, which is not always the case, and they play playfully and directly.

Dušan Kojić Koja (Disciplina kičme/Disciplin A Kitchme) – brilliant and imaginative bass player. He knows when to play a lot and when to play a little. The bass is always strong and dominates. One of my most favorite musicians.

Holger Czukay (Can) – great minimalist, economical approach to the bass. The highlights are the bass for ‘Vitamin C’ and ‘Halleluwah.’

Apart from bassists, my favorite musicians are Jaki Liebezeit (Can), Syd Barrett, Mance, Ted Milton (Blurt), Gerard van Herk (Deja Voodoo), Jonathan Richman, Malcolm Mooney, and Damo Suzuki, all members of Amon Düül…

Thank you. Last word is yours.

Thank you for the opportunity to introduce myself on such a brilliant site that exudes great enthusiasm!

Klemen Breznikar

Translated from Croatian to English by Vanesa Matošević

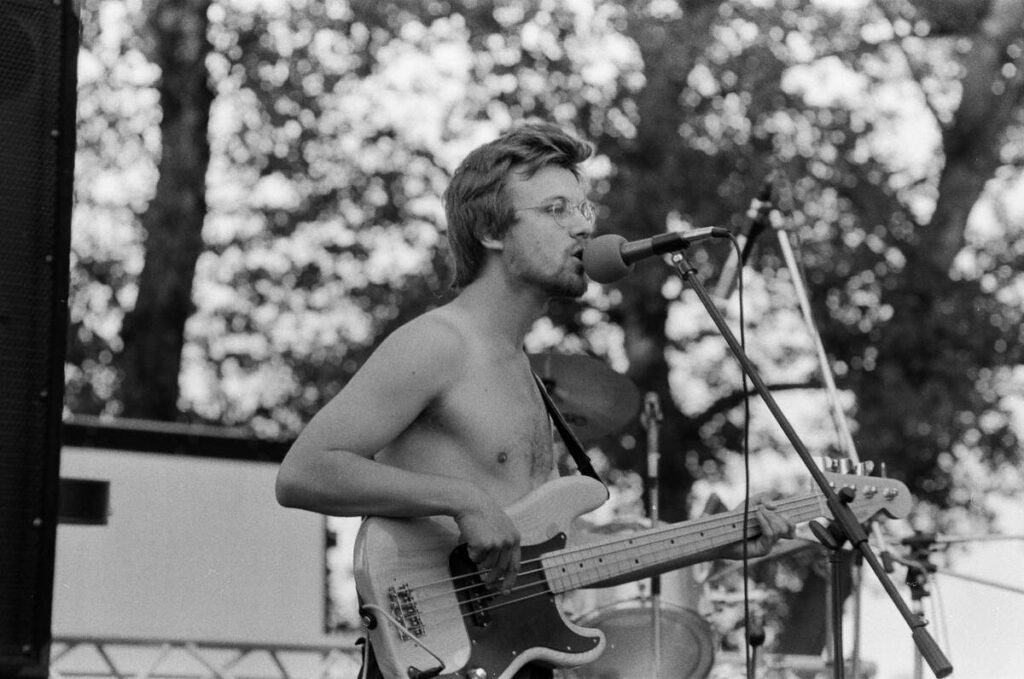

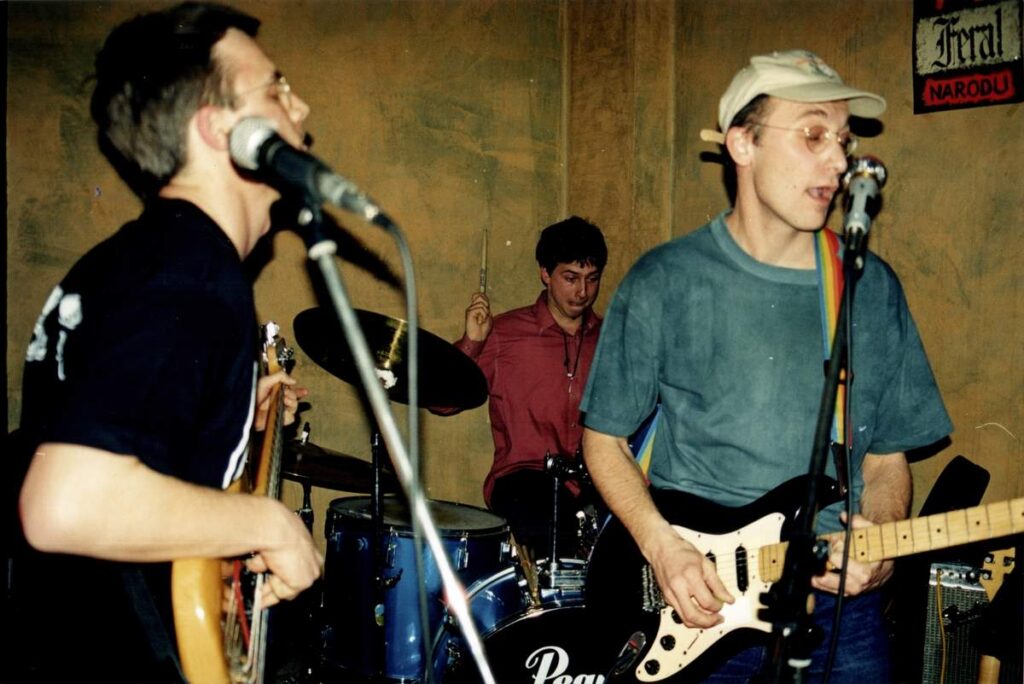

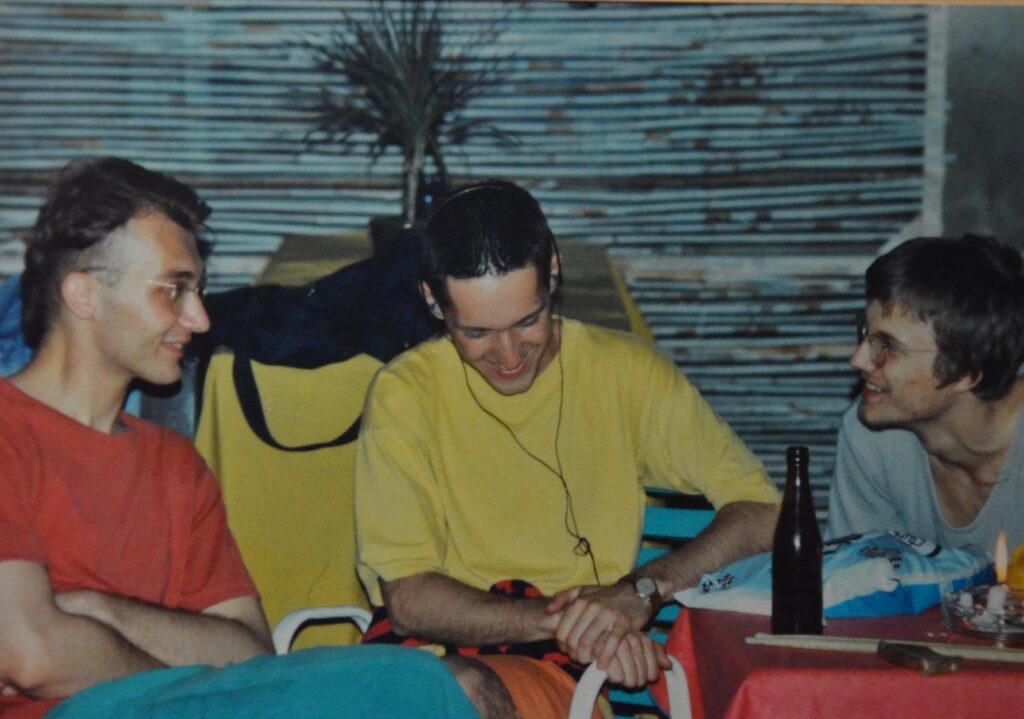

Headline photo: Šumski (1997) | Photo: Marko Čaklović

Šumski Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube