Jack Ruby | W-2 | Interview | “The Velvet Underground in a car crash”

Jack Ruby emerged from the vibrant music scene of Albany, New York, in the summer of 1973, bringing together a unique blend of punk and avant-garde influences.

Fronted by vocalist Robin “Robby” Hall, the band’s lineup also featured guitarist Chris Gray, multi-instrumentalist Randy Cohen, and the classically-trained Boris Policeband on viola. The addition of bassist George Scott and new vocalist Stephen Barth further shaped the band’s distinctive sound.

Despite their groundbreaking approach, Jack Ruby only managed to release five studio recordings during their active years between 1973 and 1977. Their music, characterized by experimental and raw energy, remained unreleased until years later, including their standout track, ‘Hit and Run.’ The band’s five live performances were equally influential, showcasing their innovative style and capturing the essence of their avant-garde vision.

Their sound was a rebellious reaction against the mainstream music of the 1970s, with a raw, aggressive edge that was ahead of its time. The combination of Gray’s intense guitar riffs, Cohen’s experimental instrumentation, and Boris’s viola provided a complex, layered musical experience.

Jack Ruby’s recordings, including ‘Hit and Run,’ were rediscovered and celebrated decades after their initial creation, highlighting their enduring impact on the music scene. The band’s legacy is a testament to their pioneering spirit, as their music, once considered lost, has finally been recognized for its revolutionary influence on punk and avant-garde genres.

“The Velvet Underground in a car crash”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Robin Hall: I grew up in a small town in northern New York State. I was born in 1952, so my pre-adolescent years took me through the Beatles phenomenon. I was definitely a fan, but because of the limited access to records (there wasn’t a record store within 40 miles of the town I grew up in), the first album I remember owning was a Dave Clark 5 album (because it was on a rack in the local drugstore). My love of music grew when I got a transistor radio. The Top 40 station we listened to was WPTR in Albany, NY. The first song I remember searching the dial to hear was ‘Hang On Sloopy’ by the McCoys. That kind of focused my interest on garage rock—’Dirty Water,’ ‘Gloria,’ ‘Shapes of Things,’ ’96 Tears,’ ‘Wild Thing,’ ‘Louie, Louie.’

I spent my teenage years in boarding school, where I listened to the Boston progressive rock station WBCN. They were famous for playing anything and everything. I was a hippie. I wanted to move to San Francisco. BCN taught me to love most music. After high school and a brief stay in SF, I moved to Boston with my then-girlfriend. Pretty much all I did was listen to music. That’s when I fell out of love with the Allman Brothers and Leon Russell and fell in love with the Velvets, the MC5, the Stooges, and Alice Cooper. Also Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, and the Rascals. I was introduced to Patti Smith via her poetry in a Boston music magazine called Fusion. I went to college for a year and a half but dropped out to work in a record store in Albany, NY.

Was there a certain scene you were part of? Maybe you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

In Albany, in 1972 and 1973, there wasn’t much of a scene compared to what was about to happen in NYC. There was a bar band called George Arliss and the All Night Shakers, and they covered a lot of Velvet Underground. Once I moved to NY, in the fall of 1973, I went to a lot of clubs. I lived two blocks from Max’s Kansas City and went there a lot. I remember seeing Big Star (a band we loved even though we had no desire to sound like them) playing for a very small crowd. I saw Television’s first gig at a venue called the Townhouse Theater. I also saw the Modern Lovers’ last gig at the same venue.

I went to CBGB’s for the first time in January 1975. The first night, I saw Mink DeVille and the Ramones. I went back the next night and saw Talking Heads and Television. I loved all those bands and went back to CB’s too many times to count.

If we were to step into your teenage room, what kind of records, fanzines, posters, etc., would we find there?

In my early teenage years, it would have been mostly 45s—pop stuff like Tommy James and the Shondells, the Turtles, Sonny and Cher, Manfred Mann—but also punkier stuff like ‘Dirty Water,’ ‘Hang on Sloopy,’ and ‘Wild Thing.’ Later, when I was at boarding school, I started buying albums, mainly English rock and blues like Jeff Beck, Cream, and Hendrix, as well as SF bands like Quicksilver and Big Brother. I do remember buying the first Velvet Underground album on the same day I bought Sergeant Pepper’s, in the summer between 9th and 10th grade. I wasn’t big on posters, and back then there weren’t really any fanzines.

Were you or any other members of Jack Ruby in other bands? Are there any recordings of it?

Strangely enough, none of us had been in bands before Jack Ruby.

How did you decide to use the name “Jack Ruby”?

I believe I thought of the name. I thought it would be good because we could use the image of Lee Harvey Oswald shooting Jack Ruby as our logo.

Can you tell us more about the early days of Jack Ruby? What brought you and the original members together in Albany, New York, in the summer of 1973?

On the first day the record store in Albany opened, I met Chris Gray. He and I immediately bonded over our love of the Stooges and the Velvet Underground. But this was in 1973, so we also loved glitter, especially Slade, T. Rex, and the Sweet. We started wearing makeup and nail polish. Albany wasn’t ready for that, but there were a few of us. Chris and I would get drunk and talk about starting a band. Nuggets had come out the summer before, and we were both inspired by the rawness, simplicity, and aggression of that music. I read about the NY Dolls. They sounded fantastic. I visited some friends in NYC, and we saw them at the Mercer Arts Center. I had also started listening to Can, Faust, and Amon Düül. Chris had majored in music at Albany State University and had a knowledge of modern avant-garde music. We started formulating a concept of a band that would encompass all these elements.

There was a bass player in Albany who we discussed playing with, but we didn’t do any playing until we both moved to NYC. In NYC, Chris introduced me to Randy Cohen, who he’d known at Albany State. He, in turn, introduced us to Boris Policeband. Even then, in 1974, Boris played his violin through an FM transmitter attached to his belt. Randy had recently graduated from CalArts, and he lived on Thompson Street in Soho. He had one of the first three Serge synthesizers, which he had helped build when he was at CalArts. When we had to rehearse, we had to lug it down the stairs and into his VW bus.

What were some of the major musical influences for Jack Ruby during its formation? How did these influences shape your sound and style?

As I mentioned, Chris and I loved the Velvets and the Stooges. We also loved Top 40 radio. We both loved The Move and Slade. Also, Captain Beefheart, Eno, Abba (true!), the Four Seasons, and Hawkwind. Chris really appreciated Black Sabbath and other heavy metal bands as well. Randy was more intellectual. He introduced us to the music of artists like Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and Xenakis.

Tell us when you first heard God Bless The Red Krayola And All Who Sail With It. What fascinated you about it?

I had read about International Artists, the label that put out the Thirteenth Floor Elevators, in Creem, and one day I came across several IA albums in a record store (Red Krayola, The Golden Dawn’s ‘Power Plant,’ Lost and Found). I bought all of them, and the Red Krayola was by far the most interesting. I gravitated towards ‘Jamie Jones.’ I loved the minimalism of the music and the slightly absurdist lyrics. I still love that song. Last year, I actually did a cover of it.

“Lydia Lunch got to know Chris and George and started coming to rehearsals”

How was Jack Ruby’s music received by audiences during your early gigs? Do you have any memorable anecdotes from those early performances?

I can only speak to the audiences we attracted during our rehearsals at Matrix Studio in NYC. (I don’t know how it worked in other places, but in NYC, a lot of bands had to rent rehearsal space by the hour. Matrix was on 27th St. It cost $10 an hour.) Our rehearsals began to be quite popular. Lydia Lunch got to know Chris and George and started coming to rehearsals. She brought other people, like James Chance. Eventually, the rehearsals got so crowded that Matrix said we couldn’t have visitors.

What did your repertoire consist of?

Basically what’s on the CD: ‘Hit and Run,’ ‘Bored Stiff,’ ‘Sleep Cure,’ ‘Bad Teeth.’ We also covered Hawkwind and the Four Seasons.

How did the different backgrounds and musical expertise of members like Chris Gray, Randy Cohen, and Boris Policeband influence your creative process?

I would say Chris and I were the ones who most believed in the romantic idea of a rock band. Randy might have been the first ironic punk. He got it, but he also enjoyed making fun of it. Boris was a musical anarchist who really wanted to explore disruption and chaos.

What impact did new members like bassist George Scott and vocalist Stephen Barth have on the band’s dynamics and sound?

George hadn’t played bass before he met Chris. But pretty quickly he developed his own style, which reached its fruition with the Raybeats and 8-Eyed Spy. Imagine someone playing bass with a cast on their arm up to their fingers. That was George’s style. I actually never heard Steve with the band, but from what I understand, where my style was much more straightforward Iggy Pop style, his was more performance art.

Boris Policeband was a classically trained viola player. How did his classical training integrate with the avant-garde and punk elements of Jack Ruby’s music?

I think his influence can best be heard in ‘Mayonnaise,’ although his personality was a big part of what made the early Jack Ruby fun. Boris would come to my apartment, sit down in front of the television (when there was no such thing as a remote control). He claimed he’d been fired by the Oakland Symphony Orchestra for wearing white sneakers to a performance. I never saw him without his white Converses.

Can you share insights into the recording process of your five studio recordings? What challenges did you face, and how did you overcome them?

‘Hit and Run’ and ‘Mayonnaise’ were recorded in a studio somewhere on the west side of Manhattan. Randy and Chris produced ‘Hit and Run.’ Randy played drums, and Chris played bass and guitar. Boris produced ‘Mayonnaise.’ ‘Bored Stiff,’ ‘Sleep Cure,’ and ‘Bad Teeth’ were recorded at Columbia Studios in what later became Studio 54. We had a staff engineer (supposedly the guy who had engineered the Edgar Winter album ‘They Only Come Out at Night’). The biggest challenge was that he didn’t get what we were doing. He didn’t want the amps to feedback. He didn’t want things to sound atonal. He didn’t really like what we were doing. But we had a pretty clear idea of what we wanted, and he tried to oblige.

Was there any interest from labels back then? Did you ever consider self-releasing it back then?

The Columbia Studio recordings were done for an A&R guy at Epic Records. But they didn’t like what they heard. We got the demo to several other record companies, but they all passed. (Paul Nelson, who had signed the NY Dolls to Mercury, heard our demo and called us “the Velvet Underground in a car crash,” but he was no longer a record exec.)

Your music was not released until years later. What were the reasons behind this delay, and how did it feel when your work finally saw the light of day?

Jack Ruby broke up at the end of 1977. There was no big deal about that. The band just faded away, and with it, the memory of the band. We didn’t have enough of a following for anyone to mourn it. Chris moved back to Albany. George was playing in the Contortions. I was staying away from music because I was trying not to use drugs. Even when I decided to start W-2, I never spoke about Jack Ruby. Neither did George.

I had a cassette of ‘Hit and Run’ and the three Columbia demos, but I never talked about it and rarely played it. In 2011, I got a call from a guy named Gary Reese, who had been George Scott’s roommate in NYC. Since George had passed away, Gary had taken it upon himself to keep his memory alive. He tracked me down because he had a cassette of the Columbia demo and was trying to find any survivors of Jack Ruby. He was friends with an old girlfriend of George’s, who also had a rehearsal tape. After he called and asked if I was the Robby Hall who had sung in Jack Ruby, he got in touch with Weasel Walter and told him about me. It turns out that two books had been written about No Wave that mentioned Jack Ruby as this mysterious quasi-mythical band that had been an influence on No Wave via Lydia and James, but no one knew anything about us, except that it was the first band George had been in. (Many people thought George had been one of the founders of Jack Ruby. I was able to fill people in on the earlier history.) Weasel, who was one of the biggest cheerleaders for noise music, got very excited and said he wanted to put out a CD. Coincidentally, two French guys got in touch and wanted to put out Hit and Run as a single. The CD was released and got some good reviews, including a big spread in the Village Voice. Gary introduced me to Thurston Moore, and he was very excited and wanted to put the music out on vinyl. Meanwhile, Lydia had told Chris Campion, an English music critic with his own small label, about us, and he wanted to put a CD out in England. Coincidentally, a box of recording tape was found in a storage space rented by Randy Cohen’s mother, and it included a half-inch master of the demos and a copy of ‘Mayonnaise,’ which we thought had disappeared. It also included a tape of synth/guitar jams between Chris and Randy. So it was decided to get Don Fleming to restore/remaster the tracks that Weasel had released, using the newly discovered tapes, and to release a double CD and two vinyl albums. Thurston wrote a big article for the Guardian about us, and we got several major reviews in Mojo, Rolling Stone, and Wire. Then Martin Scorsese, who was in the process of creating the show Vinyl about the music business in the ’70s, heard the CD and decided we would be the model for the Nasty Bits, the punk band in the show who inspires the main character to change the course of the music business. Lee Ranaldo, Don Fleming, Steve Shelley, and some other well-known musicians covered four of our songs, and James Jagger, who was playing me in the show, sang my vocal parts. In 2016, Randy Cohen interviewed Lee Ranaldo and Don Fleming about Vinyl and Jack Ruby for his podcast, and I performed four songs with Lee, Don, the guitarist Alan Licht, the bass player Sal Maglie (Roxy Music, Sparks), and Simeon Caine (Black Flag). Here’s a video of ‘Bad Teeth’ from that performance.

‘Hit and Run’ is considered Jack Ruby’s signature tune. What is the story behind this track, and how did it come together in the studio?

Unfortunately, I can’t remember. To me, the beauty of that song is the guitar parts Chris laid down.

The mid-70s was a tumultuous time culturally and politically. How did the socio-political climate of the time influence Jack Ruby’s music and message?

I think the four of us, like many of the young musicians who gravitated to NYC in the early and mid-70s, had grown up with the Beatles and what came after, but were disenchanted with the music we were hearing (prog rock, country rock). Speaking for myself, I was also disillusioned with the politics of the time. I had demonstrated against the Vietnam War. I cheered for what I thought of as the coming hippy revolution. I felt like both were failures.

What was your artistic vision for Jack Ruby, and how did you strive to convey that through your performances and recordings?

I can only speak for myself and reflect a bit on what Chris thought, because I think we shared a vision.

We wanted to have hit records. We both were raised on Top 40 AM radio, and our goal was to subvert the music business and pop culture by making avant-garde, obnoxious, difficult music into hit records.

When did the band stop playing together? What followed for the members?

Randy left the group in 1974 and gave up music altogether to become a writer. Boris, who left Jack Ruby soon after we made our first demo, continued as a solo artist. George went on to play with James Chance in the Contortions, then formed the Raybeats with Pat Irwin and 8-Eyed Spy with Lydia Lunch. (He also played briefly with John Cale.) I left Jack Ruby in 1977 because of issues I had with drugs, and I didn’t play any music for two years. Then in 1979, I formed a band called W-2 with a guitarist named Russell Berke.

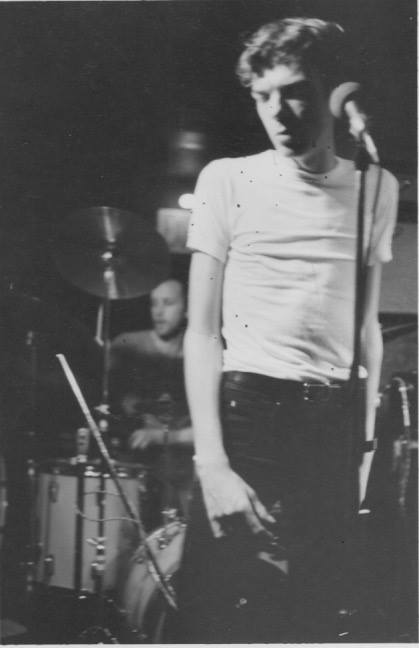

We weren’t together very long, but we played gigs at TR3, CBGB, and Hurrah (we opened for both Monochrome Set and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark). We recorded a four-song demo, which I thought was lost, but actually surfaced recently. I will attach a link to those songs. I heard that Chris was in a band in Albany for a while, but I don’t know for how long or how successful they were.

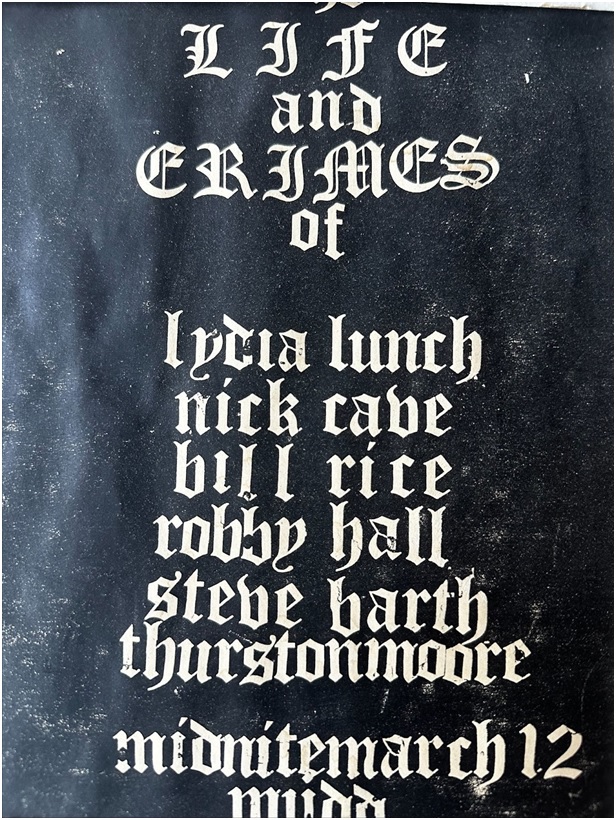

Steve Barth and I performed at the Mudd Club at a reading organized by Lydia Lunch in March 1983.

Are there any current projects or collaborations you are working on that you’d like to share with your fans?

After many years of not performing or creating music, I am now writing songs again. Here is a song I wrote that touches on the ups and downs of the 1970s.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band?

Personally, I love ‘Mayonnaise.’

Klemen Breznikar

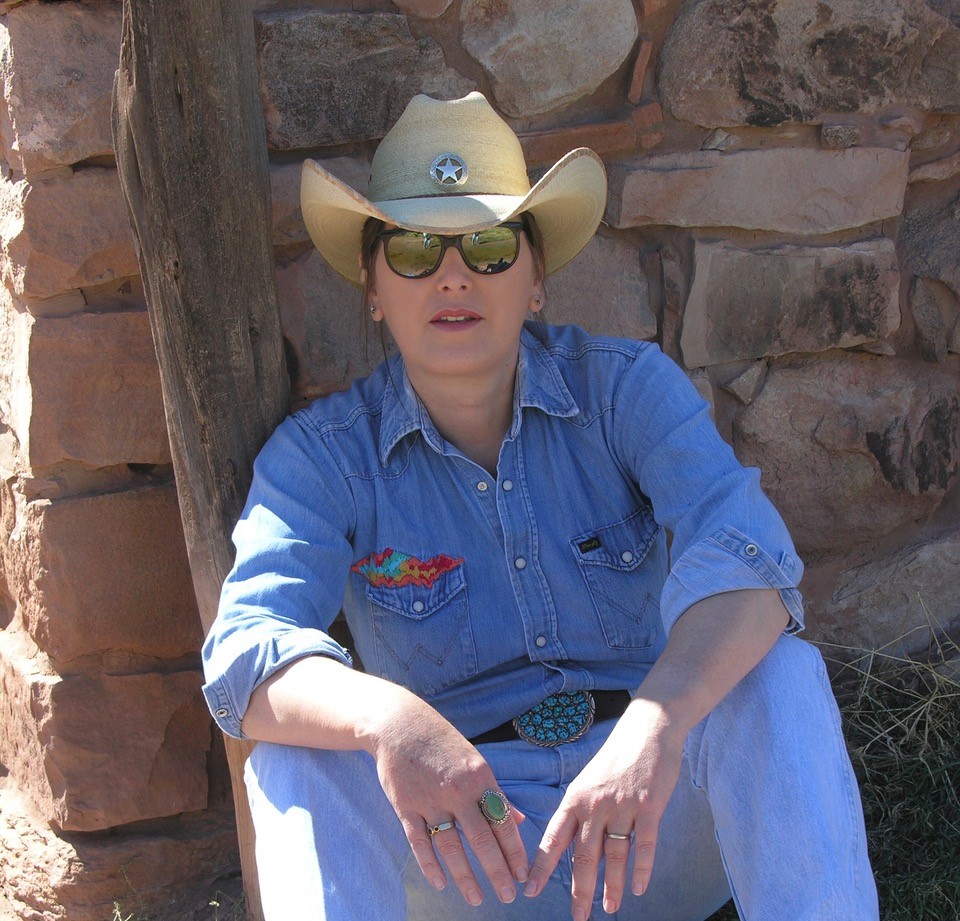

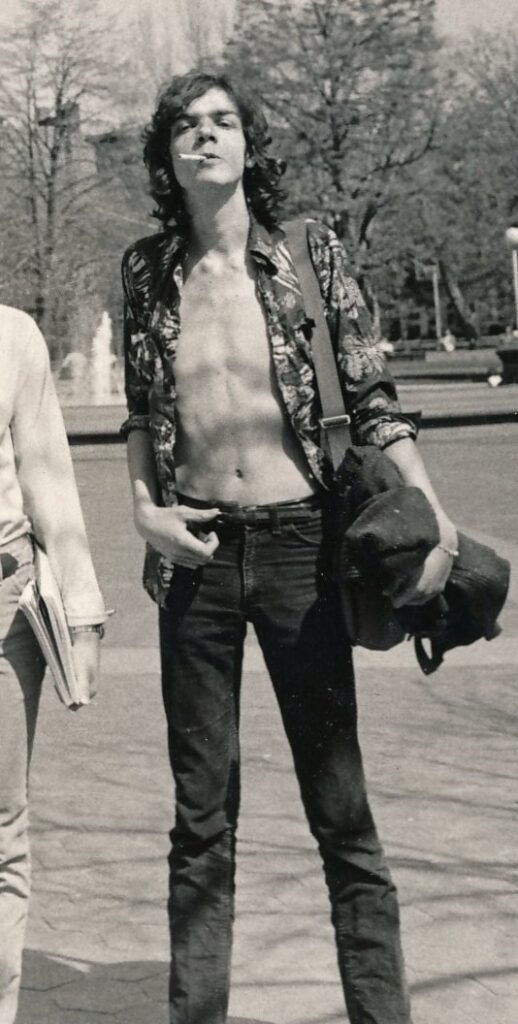

Headline photo: W-2 (1980)

Jack Ruby Facebook