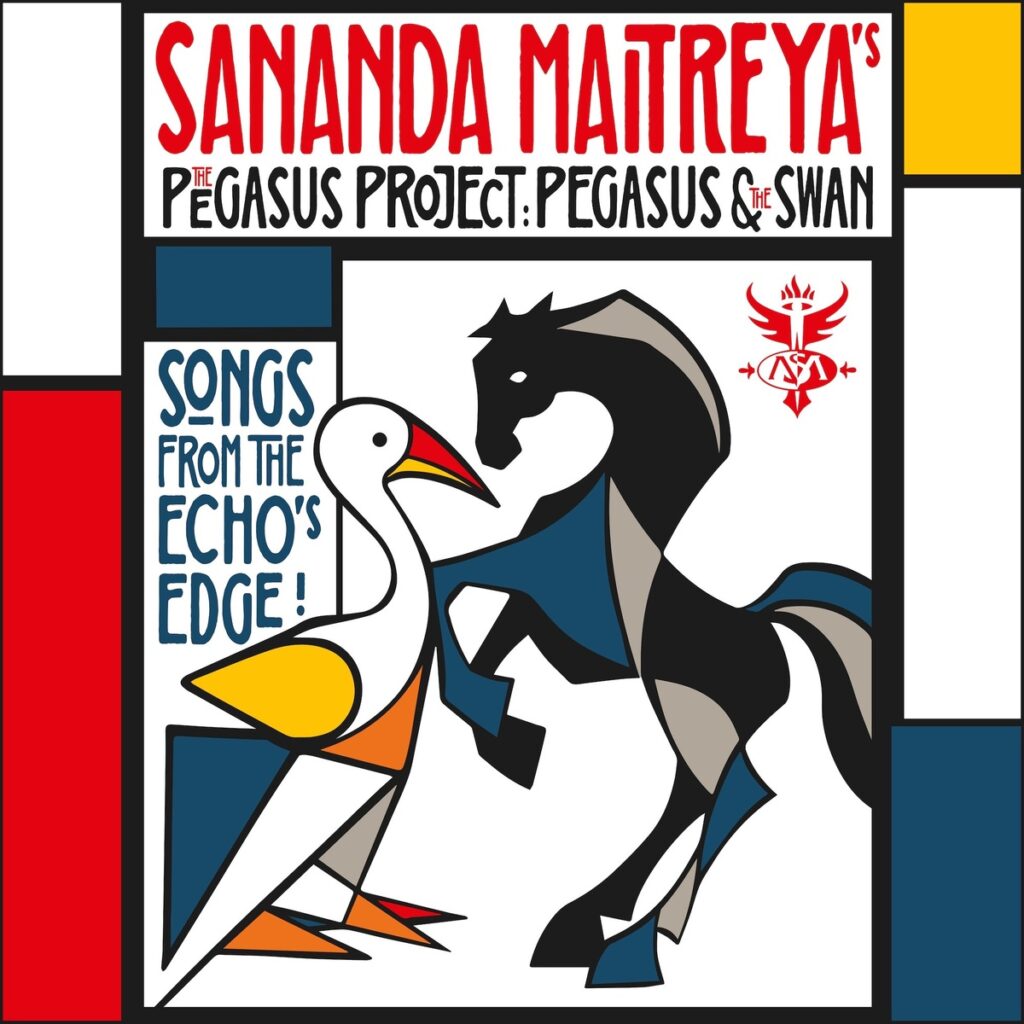

Sananda Maitreya | Interview | New Album, ‘The Pegasus Project: Pegasus & The Swan’

Sananda Maitreya, the visionary artist known for his genre-defying approach, recently released ‘Pegasus and the Swan,’ a bold new project that blends orchestral grandeur with his signature eclectic sound.

This album, part 3 of his recent album series, marks a new chapter in his musical journey. Divided into two distinct sides, the album delves into mythological and spiritual themes, exploring the transformative power of creativity. Known for his fiercely independent spirit, Maitreya rarely collaborates, but this time he joined forces with conductor Diego Basso and the Budapest National Art Orchestra to elevate his sonic palette. Tracks like ‘New World Forming’ and ‘Madame Swan’ revisit past works, now infused with renewed depth and relevance for today’s world. With influences ranging from Frank Sinatra to Lou Reed, his music continues to defy genre and expectation. Maitreya’s ever-evolving artistry challenges the norms of modern music, combining narrative complexity with emotional resonance. ‘Pegasus and the Swan’ promises to be not just an album, but a dynamic musical journey, inviting listeners into a world where mythology and self-reflection collide.

“My evolution is the natural evolution of an artist”

With the ‘Pegasus Project, Pegasus and the Swan,’ you’ve taken quite a journey from your debut in 1987 to now. How would you describe the evolution of your music, particularly in the context of this latest album?

Sananda Maitreya: I would begin by saying that basically, my evolution is the natural evolution of an artist that you would expect when that artist has not been hindered or hampered by interference from outside parties or outside sources. I have had the great, great, great fortune of, for the most part, being able to spend most of my career listening first and foremost to the muse, which is my responsibility, and I haven’t had to consider too much other people’s idea of who I was and who I represented to them as an artist, which I never felt was as compelling as how I understood in my own imagination I was capable of fulfilling my destiny as an artist. So, from the debut in ’87 to now, you’ve basically witnessed the natural evolution of an artist left to their own imagination and their own passion, as well it should be. But most artists do not necessarily have this opportunity that I was given, and because I was given it and understood the rare opportunity that was, it just fueled my determination that much more to make sure that I did not waste that opportunity.

Your albums often seem to carry a thematic thread. What inspired the concept behind ‘Pegasus and the Swan,’ and how does it weave through the tracks?

‘The Pegasus Project: Pegasus & the Swan’ is the ending of a trilogy that began with ‘Prometheus & Pandora’ and the predecessor album to this one, ‘Pandora’s PlayHouse.’ So, from ‘Prometheus & Pandora,’ ‘Pandora’s PlayHouse,’ to the ‘Pegasus Project,’ we’ve basically exhausted our alliteration of the letter “P.” You’ll notice the theme is that we have used the story of Prometheus as basically a proxy story that stands in for the life that I have lived myself and seen. I could relate very, very easily to the idea of a god who was banished from the top of Mount Olympus because of the jealousy and confusion of the other gods as to what Prometheus was a harbinger of and what he represented. And so, basically, it became politically expedient for Zeus, his father and the king of the gods, to banish him because he understood that if he didn’t, he was going to lose the support of the gods that were already there on Olympus. He understood how much he needed those gods because they had helped him overthrow the Titans, which were led by his father. Prometheus’ story is one that I’ve always, along with the story of Orpheus, had the most powerful emotional connection to. So, I saw myself in his story, and that’s what allowed me to use it to basically express a lot of the concerns and the emotions that I had as an artist.

Your collaborators on this album range from seasoned pros like Andy Wright to fresh talents like Oscar Derrick Brown. What was the creative dynamic like in the studio, and how did this collaboration shape the final product?

It was not really much different from the way I’ve always worked, which is basically without collaborators, where I do everything by myself, which is always a great pleasure for me and a great joy that I take very seriously. This one was very interesting because, basically, every so often I get asked to collaborate with others on projects, which I tend to graciously refuse because, when I’m not working on my own stuff, which doesn’t leave me a lot of extra time anyway, I like to spend time with my growing family, my boys, Francesco Mingus and Federico Elvis. So, this was an instance where I had a gentleman by the name of Diego Basso, whose orchestra I have worked with in the past for live concerts. He asked me every two years if we could do a project together. I finally got tired of saying no or got tired of postponing the idea. So, right before COVID, we decided we were going to finally do something together. Then COVID happened, so we had to postpone it, obviously. By the time we were finally able to work together, the idea was that we would take five or six of my songs and arrange them for the orchestra. So, we did that. That inspired me to also commission a string quartet to collaborate with me on another three or four pieces. Then I determined that, since that part of the project, the Swan side of the project, was taking that shape, I was going to honor a couple of other things that had been offered to me in the way of collaborations.

Oscar Derrick Brown was a situation where he approached me to help him with a film score. I agreed under the provision that I would take a couple of the songs and use them if I thought they would fit ‘The Pegasus Project.’ Andy Wright was a situation where BMG, who administers my publishing company, TreeHouse Publishing, had been pestering me for almost five years because Andy Wright had been asking them off and on if he could get a song to me, as he thought I would be perfect for something he wanted to collaborate on. So that’s how that happened. I just decided to let all of those things happen at once. It seemed like the time was right for it. So what we have is the Pegasus side, where I’ve done everything as I normally approach my music, playing everything myself. And then the second side, which is half of it, is dedicated to those particular collaborations, which are all congealed on the second disc. That’s the story of that. It was just a perfect storm where everything kind of came together, and it felt like the right time to finally allow those collaborations to happen.

There’s also a collaboration with the great Jelly Bean Johnson, one of the formidable leaders of the great supergroup from the ’80s, The Time. He basically asked if I would help him with his record, and we both agreed that I could use it if I wanted to. So, it just felt like it was the collaboration season for that particular project, and I let it happen. It was special for me because I don’t do that often and probably won’t do it again for a while, but it just seemed like the right time to do it. There’s also the fact that I had the wonderful participation of two ladies, Luisa Corna and Beatrice Baldaccini. So it just felt like it was time for all of that to happen, and it did.

The album is divided into two sides, Pegasus and The Swan. Can you walk us through the distinct vibe and sound of each side and what inspired the division?

Well, the side to The Swan side is the side that more or less expresses the perspective that I would imagine filtered through the energy of what a swan represents. A swan, for me, is more of a lunar, a symbol of lunar power, mystery, and beauty. The fact that the moon and the lake are so closely connected in our psychological terrain, the swan embodies this for me—something that is mysterious and unknowable. It can be seen and appreciated, but you never really know a swan the way you feel like you know a pigeon or a robin or an owl. There is something of the mystery of a swan. So we determined that since the moon is much more of a collaborative type of energy, that’s the side that we were going to put collaborations on as filtered through The Swan side.

Pegasus, being a horse, a flying horse, is much more of a solar representative energy for me and represents more of that, the hero archetype of the Promethean figure who’s unafraid to go alone and will walk into the forest or the jungle alone if called by necessity, to take courage in whatever they need to take courage in. So side one is me pretty much doing what we’ve always done since the beginning of Post-Millennium Rock, which is to handle everything in that particular way—much more of an insular vision—and then to have expanded it on the side of the swan.

You already answered before, but incorporating the Archimia String Quartet and the Budapest National Art Orchestra adds a majestic layer to your sound. What prompted you to work with these orchestras, and how did they influence the album’s sonic landscape?

I’m a huge, huge fan of Frank Sinatra. I’ve been since I was a child, and it has always been my intention to do a Sinatra album, a big band album. I just didn’t find the right time. Then about a decade or so ago, whenever it was, I heard Michael Bublé, the great Michael Bublé, and I realized that he had done precisely what I had wanted to do eventually when I made my Frank Sinatra record. So, therefore, he had done it so brilliantly that there was no point for me to come behind him and do what he’d already excelled and exceeded expectations at doing. So it was just a matter of postponing the idea, but of course, any artist will tell you that working with an orchestra is a different and unique experience, and I always knew it was something I would do. I just kept postponing it because Post-Millennium Rock kept presenting me with newer and newer adventures. But again, Diego Basso, the great conductor of the Budapest National Orchestra, is a friend of ours, and I’ve known him for about 20 years. So eventually, I got tired of turning him down when he would offer his orchestra for recording, and I just decided it was time for me to stop running away from what I had always wanted to do anyway and just capitulate to it.

Also, the string quartet, that’s another thing that I’ve always wanted to do, but I’ve usually done the strings, arranged the strings myself. This was the first time where, basically, it was exclusively string sections for a few pieces, and I was able to collaborate with the Archimia to make the arrangements that would justify inclusion on the Pegasus Project. I’m immensely happy and relieved with the way it turned out. If you find the right musicians, it’s very difficult for something not to sound majestic when you’ve got a great orchestra and a great chamber group behind you.

“I was very blessed to have been mentored by Miles Davis”

Your playful interlude, ‘BDSM,’ pays homage to your mentor Prince. How has Prince’s influence shaped your musical journey, and how does it manifest in your latest work?

There are certain people who are signposts. I’ve often believed that the people who most influence you are the people that have shown you that you were also that. You know, there’s a lot of people whose music I have great respect for, but they didn’t necessarily influence me because I didn’t hear myself in what they were doing. As an artist, I might have just enjoyed what they were doing as a listener. Along with Stevie Wonder, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones of course, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, The Beach Boys, Steely Dan, Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke, Sly and the Family Stone, Michael Jackson, and the Jackson Five—there were certain artists who had such a profound influence on me that they became a part of how you see your own expression, because what they’re doing speaks to you of what you also are. And you know, like Springsteen, Prince—these gentlemen, when I heard what they were doing, I knew that I was of a similar ilk, that these were my brothers, and that I belonged to this lineage. So Prince was an incredible friend to me as well. We were very, very close.

Also, Miles Davis— I was very blessed to have been mentored by Miles Davis. I’d say the same, I would call Bruce Springsteen a mentor. I was also greatly influenced by Rod Stewart. And everybody that has had a profound influence on my life, like Frank Sinatra—if you listen to my music over the years, you can hear all of these people’s influences in the way I’ve taken that influence and shaped it into my own unique expression.

Your songs often contain rich narratives. Can you share some insights into the storytelling aspect of Pegasus and any particular themes or messages you wanted to convey?

If there’s any continuing theme, it’s the value of the presence of knowledge in our lives—of who we are—and the unsparing ability to find the courage to face the truth of who we are, and not see that as a negative, but as a positive principle through which we can know who we are and bring ourselves closer to the fulfillment that all of us seek in our lives. Whatever stories, narratives, mythology, smoke screens, or symbols that can be used to express or advance that particular narrative, I’ve never been shy in using.

I’m someone who’s always been possessed by the idea that I know, above all others, who I am and what I am capable of, and that I will make it my life’s purpose to let no one or anything stand in the way of me expressing that. I’ve always had this belief, rightly or wrongly, that the opportunity I’m given to express my creativity is unique. If I don’t express it, there will never be exactly another person like me to express it again. There may be others perhaps far, far more capable, and there probably are, but I’m confident that my expression, if it did not exist, would not exist. That’s driven me and been a huge motivating factor to continue, despite some of the odds I’ve had to encounter.

As far as specific stories, when I think of one, I will absolutely share it. But this project came together in a way that definitely felt like there was a more positive force involved, helping me compile all of this. From the beginning of this project, I felt a certain kismet and inevitability about it. One funny story is about my song ‘Bondage,’ which is a fascinating subject because, ultimately, however we view the concept of bondage, it reflects on the mental and psychological bondage that societies tend to keep us in to better control and manipulate us, guiding us towards a society they’re comfortable running and administering.

What’s interesting about ‘Bondage’ is that one of my favorite artists of all time is Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. There’s a song on the second Velvet Underground album, ‘White Light/White Heat,’ called ‘Some Kinda Love.’ For years and years, I thought Lou Reed was saying a phrase that sounded to me like “Monkey Rita Ta-Ta.” When I was writing ‘Bondage,’ I realized that was a phrase I wanted to use. One day, as I was walking to work, that phrase came into my mind, and I thought, “I’m going to recapitulate that; it’d be perfect for the song.” So I recorded it, was happy, and then my wife, Francesca, listened back to the original Lou Reed song. Much to my tremendous embarrassment, she realized what he was actually saying was, instead of “Monkey Rita Ta-Ta,” “Margarita told Tom.” I felt like such an idiot because, all these years, I’d been hearing it as “Monkey Rita Ta-Ta.” The only consolation was that, well, I ended up not stealing from him at all—it wound up being original. But he was the source of that phrase, and I think he would have appreciated the confusion because he was that kind of person anyway.

You’ve included fresh versions of songs like ‘New World Forming’ and ‘Nice Things’ on this album. What motivated you to revisit these tracks, and how do they fit into the broader narrative of ‘Pegasus and The Swan’?

All of those songs were chosen because of their relationship to the storyline of ‘Pegasus and The Swan.’ ‘New World Forming’ is one of those songs that seems very, very apropos to the world we’re living in right now. But also, since ‘Pegasus and The Swan’ is about power and transformation, if you look at the artwork on the project, you’ve got both a black and a white horse. One horse is with wings, and the other is without, but both still represent Pegasus. Similarly, the black and the white swan represent the swan’s powers of transformation—transforming their lives and energies to whatever is appropriate to achieve their goals or accomplish whatever tasks they set out for themselves. So the power of transformation and the grace of that transformation is very much a theme running throughout the album.

‘New World Forming’ fits into that idea that by changing how we see ourselves, we change the world we live in because the world is a reflection of how we collectively see ourselves. This was one of the reasons we chose to revisit those songs. ‘Madame Swan’ is self-explanatory, as it was written about the swan’s grace and the particular loneliness of being called to the life of the swan, which made it ripe to be revisited. So we did.

All of the songs chosen—like ‘Pretty Baby’—were perfect vehicles for this project because they aligned with the theme of the album itself.

How do you navigate the balance between your own creative vision and the contributions of your collaborators? Can you share any memorable moments from the collaborative process?

Well, I don’t collaborate often. I enjoy the method I’ve been working with pretty exclusively for the past 20 years. It gives me a great sense of joy and completion when I’m able to start a project from top to bottom and finish it with just me and my engineer, Matteo Sandri. There’s something not only therapeutic about it, but also necessary for the completion and transformation of my spirit, as each project always transforms an artist. It’s impossible for an artist to undertake a project and not be a different person by the end than they were at the beginning. That’s why I’ve been very faithful to the way I normally make records.

This particular project, The Pegasus Project, was definitely a bit of a departure. Side two, or disc two—the Swan—was partly given over to these wonderful collaborations I was blessed to participate in. Diego Basso, as I’ve said before, is an old friend of ours and has been for a long time. For over two decades, he’s been trying to persuade me that the time was right for us to collaborate on an orchestra project. I’ve always wanted to do one. Most artists dream of it at some point, but I just never found the right time.

Finally, just before COVID, he approached us again, and I thought, “I’ve got to stop running away from this.” If he keeps asking and I keep saying no, maybe I’m ignoring something in my own spirit trying to get my attention. So, that’s what happened. Once I opened the door to him, I decided to include a chamber quartet as well to give the project even more depth and width. It all came together so well and so naturally that I very early on felt there was something beyond just my creative will behind this project. The other collaborations—with Jelly Bean, with Andy—were about finally saying yes to requests to collaborate that I’ve usually turned down over the years. This time, it just felt right to include them.

The Pegasus Project promises to be an epic musical adventure. What do you hope listeners will take away from this journey, and how do you envision it resonating with them?

I don’t presume. Most artists don’t presume anymore to tell someone what their perceptions should be. You just hope that it has an impact and triggers something within each person, that they find something in their own journey they can relate to, or that they can relate to the emotions animating the music.

The beginning of Post-Millennium Rock was me realizing that I had the freedom, as well as the capacity and desire, to go beyond just writing songs. I wanted the songs to be part of a larger continuum, a larger whole. From the very beginning of Post-Millennium Rock, starting with ‘Angels & Vampires,’ we determined that every project would have to stand on its own as a multimedia event. That also meant that if we wanted to do a theater piece, we could take any album and do that. But we also wanted to take inspiration from Tolkien and Wagner—like Wagner did with The Ring of the Nibelungen and Tolkien did with The Lord of the Rings—to create something that could stand on its own individually, but when taken as a cohesive whole, would reveal a much greater world created to contain this music and these themes.

This vision has worked out exactly as I anticipated over 20 years ago. Others have since noticed the multimedia and thematic nature of these projects, and we’ve been offered the chance to do a musical based on my catalog, centered around the narrative of Prometheus and Pandora. So, I hope that answers the question.

As a songwriter, I needed a greater challenge. I’ve been writing songs, at least in my head, since I was a very young child. At some point, I realized that just coming up with another 12 or 14 songs, if I may say so, was a bit too easy. I needed something to raise the level of my own intention, and I was under no pressure to conform to anyone else’s idea of what I should be as an artist. Nothing stopped me from developing this vision to where it has gotten, and it’s done very well for us.

In the meantime, we’ve been offered films, musicals, books, documentaries—all showing that the direction we took was the right one. Many who thought I was out of my mind to pursue such a path now see it differently. But just because an artist is out of their mind doesn’t mean they’re not right. Sometimes, you have to go out of your mind to see the truth.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favorite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

What have I found new recently? That’s a good question. Well, you know, I’ve lived in Italy for over the past two decades. Of course, we feel obliged to mention Måneskin since they pretty much brought a spirit back to rock and roll that had been kind of absent from music for a while.

There’s also an artist by the name of Seraphina Simone, an English artist. I really like what she’s doing. She makes some very, very interesting music and has a voice of her own, though I may be somewhat biased.

I am also really digging the latest record from my old friends The Black Crowes, and the Kendrick Lamar / Drake feud did manage to produce some very cool music. I am aesthetically pleased with what Beyoncé has done with her country music project. If she wasn’t going to do it, I was. Bluegrass in particular is in my bloodline through my white ancestry, which is Scots-Irish, so I have a natural feel for that music and have always loved it.

I also like Descartes a Kant, a newer group who seem inspired by two other artists I respect: Devo and St. Vincent. And Sleater-Kinney, I’ve admired their work since the ‘90s and enjoy their latest.

Last but not least, Kacey Musgraves and Richie Kotzen—I’m a fan of his work.

Thank you. The last word is yours.

The last word is love. I believe finding new ways to see the power of love expressed in the many shapes and forms that love takes is the primary reason that motivates us as humans to live our lives. There’s something about the nature of love and its ever-expanding expressiveness and generosity. If we can center ourselves in the possibility of its power—of the idea that if the foundation of your regard for yourself is based in love—it will be the foundation of how you relate to everything else around you.

And that is the last word, because love is the first word. The only purpose, the only reason we come to earth or into a life is because of a love vibe produced between two people who put their forces together and created the human beings that we are. So, love is not only the last word—love happens to be the very first word as well.

Thank you!

Klemen Breznikar

Sananda Maitreya Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / YouTube