BaBa ZuLa | Interview | Murat Ertel

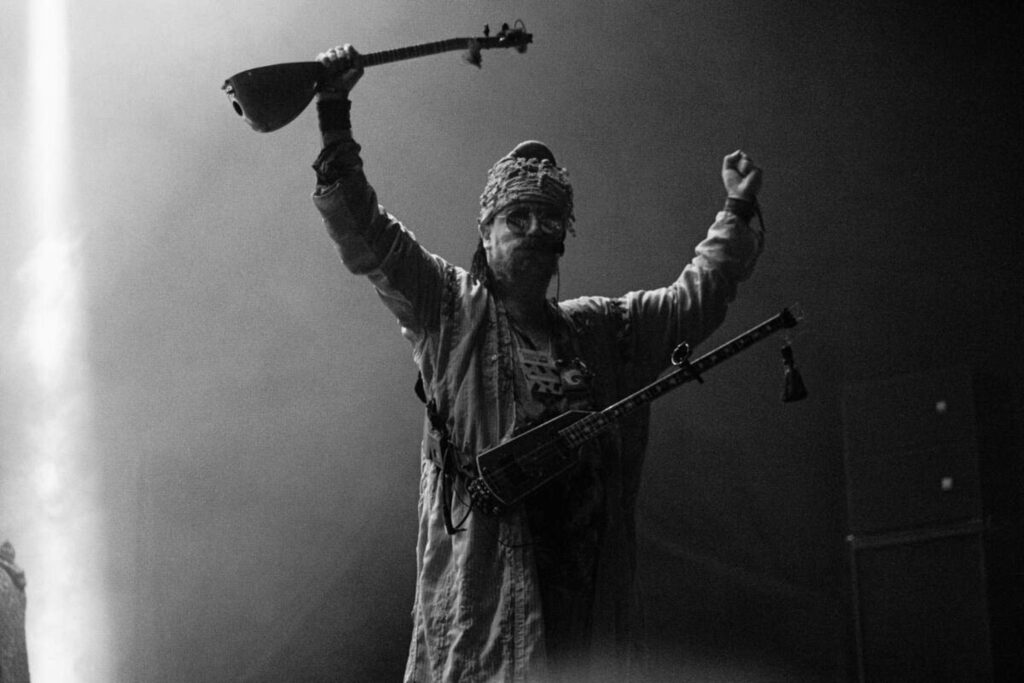

BaBa ZuLa is a band originally formed in 1996 that has released countless albums and played numerous gigs, mixing their unique fusion of traditional Turkish music and experimental psychedelic sounds.

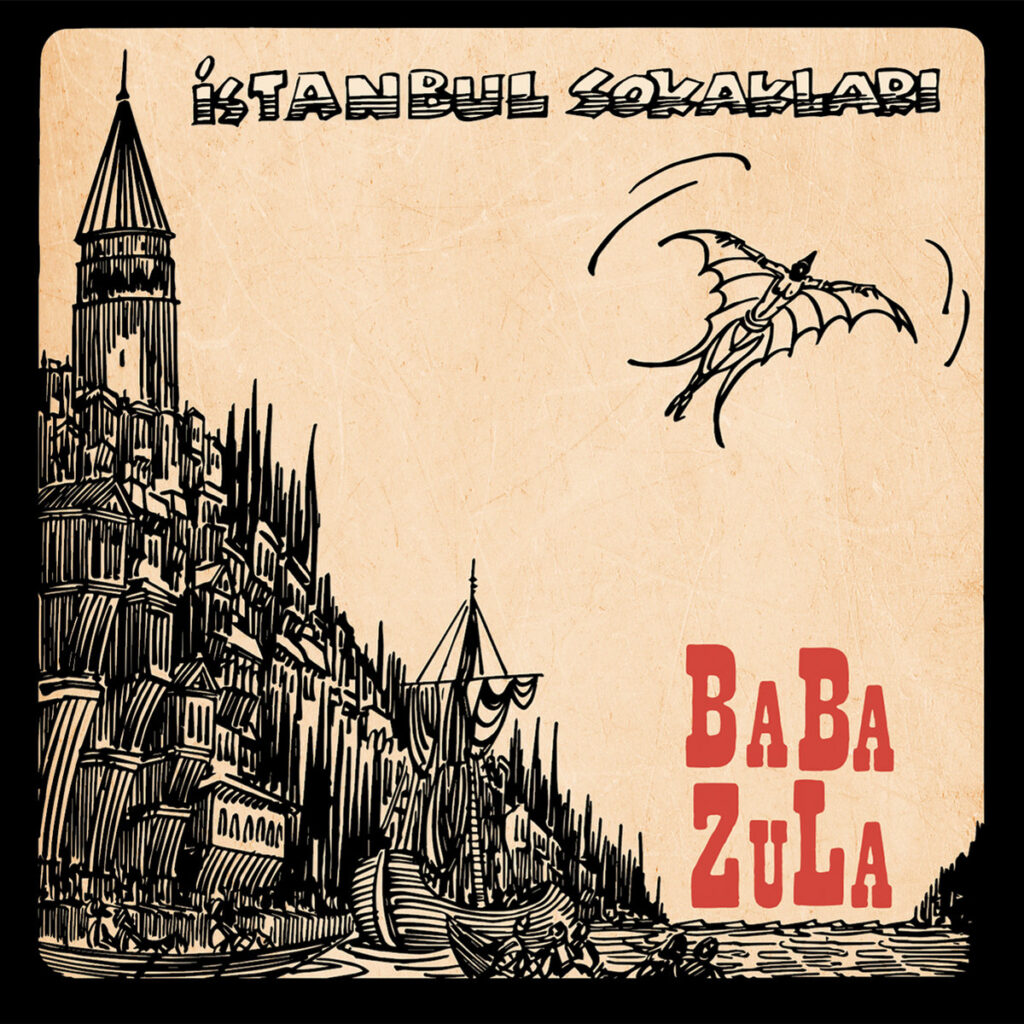

In the pre-pandemic world, they were on a relentless tour schedule, delivering nearly 100 gigs a year. Their upcoming album, ‘İstanbul Sokakları’ will be released November 8, 2024 via Glitterbeat Records. “We are embracing the past, and Turkish tradition,” says BaBa ZuLa co-founder and saz player, Murat Ertel. “But it’s not enough. We are living in the 21st century and we have all the world.” Their previous album, ‘Hayvan Gibi’ is an example of the live energy, recorded in a unique studio nestled in the remnants of Europe’s largest record printing factory.

The band’s frontman speaks passionately about the myriad influences that shape their eclectic sound, from iconic saz players to surprising guitar legends like Jimi Hendrix and Santana. Beyond their musical endeavors, he cherishes the simple joys of slowing down, nurturing family life, and mastering a newly acquired Greek bouzouki. With thrilling projects on the horizon, including a Zen documentary and the re-release of ‘Crossing the Bridge,’ BaBa ZuLa shows no signs of slowing down.

“I saw art as a powerful way to protest, to survive, and to resist.”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Murat Ertel: Well, I think my upbringing was very important because I was born into an artist family, and they were influential artists, even internationally. My father was a graphic artist—his posters and logos were all over the country, and in museums worldwide. He was holding exhibitions internationally, too. My uncles were similar. One of them, my cartoonist uncle, is Turhan Selçuk. He was drawing the Abdülcanbaz, and he was very well-known, both nationally and internationally, as a caricature artist and comic book writer and illustrator.

My other uncle was the head of a left-wing newspaper and was also a writer and journalist. Their friends were, in my opinion, some of the best artists, writers, musicians, and painters in Turkey. I feel very privileged to have grown up around them. I had access to music before it was released and knew about projects before they were public. I’d hear poems before they were printed. I was influenced by all kinds of art from the day I was born; consciously or subconsciously, I absorbed so much from these different disciplines.

But growing up in Turkey had its challenges. If you created art that touched on the country’s issues, you could get into serious trouble. My teenage years were marked by coups and the sight of my uncles being arrested, jailed, or taken to court. This was a regular occurrence, nearly for the rest of their lives. I grew up thinking that policemen and soldiers could be the bad guys—they weren’t always the heroes portrayed in movies.

I saw art as a powerful way to protest, to survive, and to resist. It was something beautiful that could unify people of all kinds. I saw books being burned and buried, and we also burned or buried books and letters to protect them. Books were censored, and people could be imprisoned for singing, writing, or drawing caricatures. It’s still almost the same today.

Back then, though, it felt even more intense because people could be killed more easily. Today, it’s harder to kill an artist, but taking them to court is still very easy. They can do it over something as small as a retweet or a Facebook repost.

Despite all that, the art and the gatherings around it—the “art feasts”—were the joy of my upbringing, and they still are today.

Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

Well, yes. Gigs happened at our house, you know? Lots of musicians came by, and they played even unreleased songs, so it was great.

Mostly, they were Ashiks like Ashik Ihsani or Ruhi Su. But, for instance, the sons of our neighbors, who were our friends, had this special house that’s even sung about in 45s. She was called Suna Abla, and Suna Abla had this very unique house. She had many guests, just like we did. And she had a young son, Ahmet. He formed what might have been Turkey’s first underground band, called Grup Bunalım. Later, he went on to play with Erkin Koray and Barış Manço. I was childhood friends with him, and when I was riding a three-wheeled bicycle, I would often go to their rehearsals. That was my favorite hangout spot—there and home. Yeah, really nice hangouts.

So, I think I was part of a scene, kind of a poetic one. For instance, we had Aziz Nesin and Yashar Kemal—they frequented our house many times. Musically, though, I don’t think we felt part of any particular scene until Fatih Akin made the movie Crossing the Bridge. Then we realized that we were part of the Istanbul sound scene and maybe the underground scene in the ’80s. Yes, we felt like that. In the ’80s, we felt part of the underground. And then, in the ’90s, we felt underground and kind of psychedelic.

By the 2000s, we felt like we were making music that captured Istanbul. We attended so many gigs, starting in childhood, and explored so many genres—Western classical, jazz, African, Turkish folk, Turkish classical, Turkish rock, and jazz. My family and I went to countless concerts. As a teenager, I kept going to gigs since my father always designed the posters and logos for festivals, so we got free tickets.

So, yes, I went to many concerts.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

I don’t know when I began playing music, but I think it was when I was kind of crawling. I took my mother’s harmonica in my mouth, and I had a toy xylophone, which I still keep. So, this xylophone and my mother’s harmonica were my first instruments. Then, growing up, I formed my first band when I was five years old with two girls. We called it Mavi Güneş 69. I recorded my first album in 1978 called ‘Nightwalker.’ Yeah.

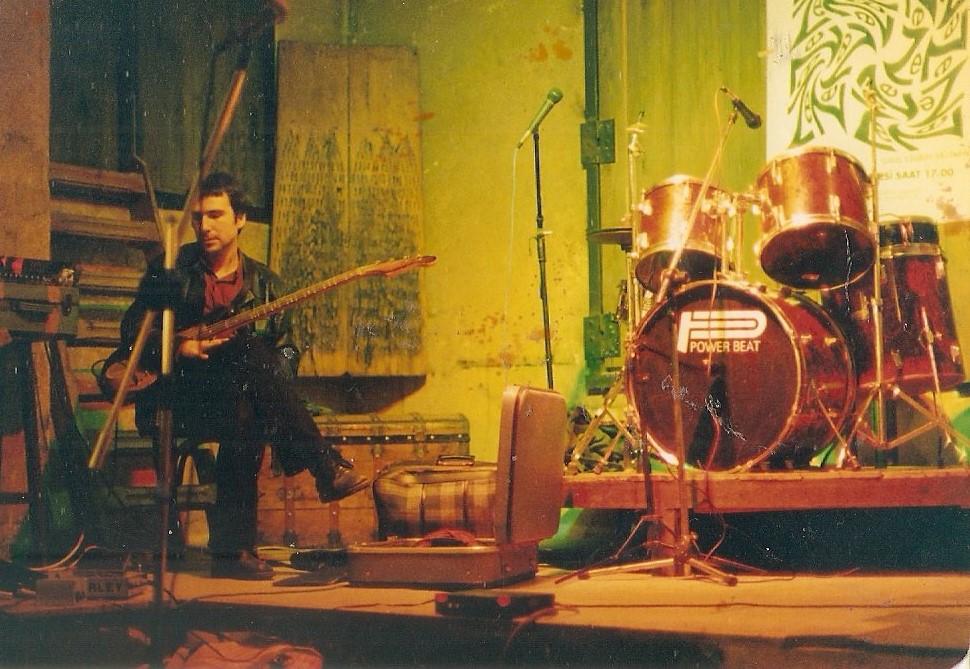

It was on one side of a cassette. It was an improvisational concept album, and I was 14. I did my first movie soundtrack in 1982, I think. Or was it 1984? I’m not sure, but it was something like that. Maybe in ’82. Yes. So, saz came into my life much later when I was in high school. But I was playing guitar, I think, in 1977 or something like that.

Major influences? Well, yes, everybody—every musician who came to our house, first. And also, my biggest influence, I think, is my father. He used to draw, and I used to watch him work. He used different techniques when he was drawing. He didn’t always use a pen or pencil; sometimes he used a hairdryer or some chemicals. It was great. He was also breaking the boundaries between graphic arts and other arts, and between East and West. So my father is a major influence for me. Then my uncles—my right uncle, yes, but mostly my comic book drawing, caricature drawing uncle, Turhan Selçuk. His comic book hero, Abdülcanbaz, was and is my major influence. I started looking at the world through his eyes and following everything from that comic book.

How did you first meet Levent Akman?

I met Levent Akman in high school, you know. He was a student, and I was a student there. I was two years older than him, and they were very influenced by me and my band. They formed a band. We helped them form a band. Then, at high school, we were playing in two different bands. I started working with some musicians from this band and from other people in the high school. When we finished high school and went to university, we started jamming with Levent Akman. So it’s a very long friendship. It’s like this Keith Richards-Mick Jagger or Lennon-McCartney thing, you know—meeting in high school and keeping company for, I don’t know, more than 40 years maybe. Yeah, I think so.

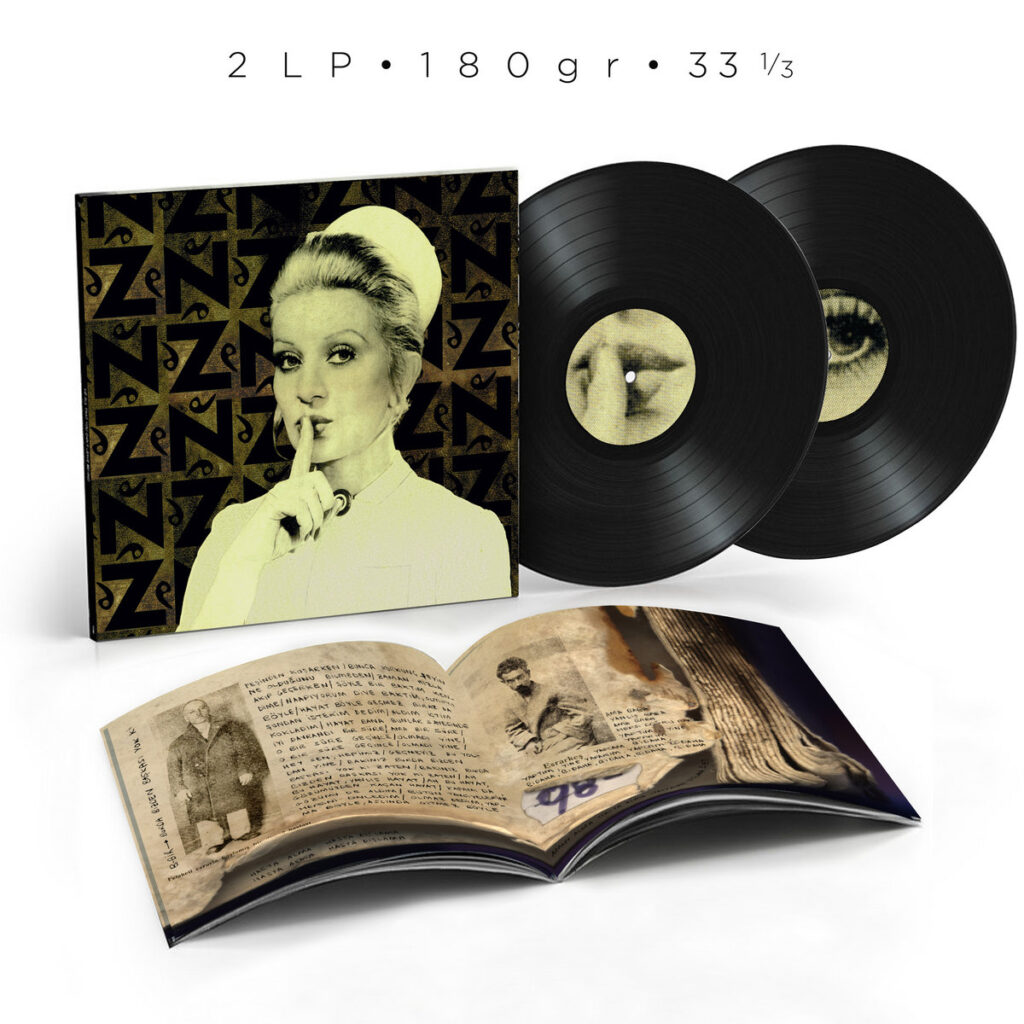

Zel Zele Records recently reissued ‘Bakırköy Akıl Hastanesi’nde’ by Zen.

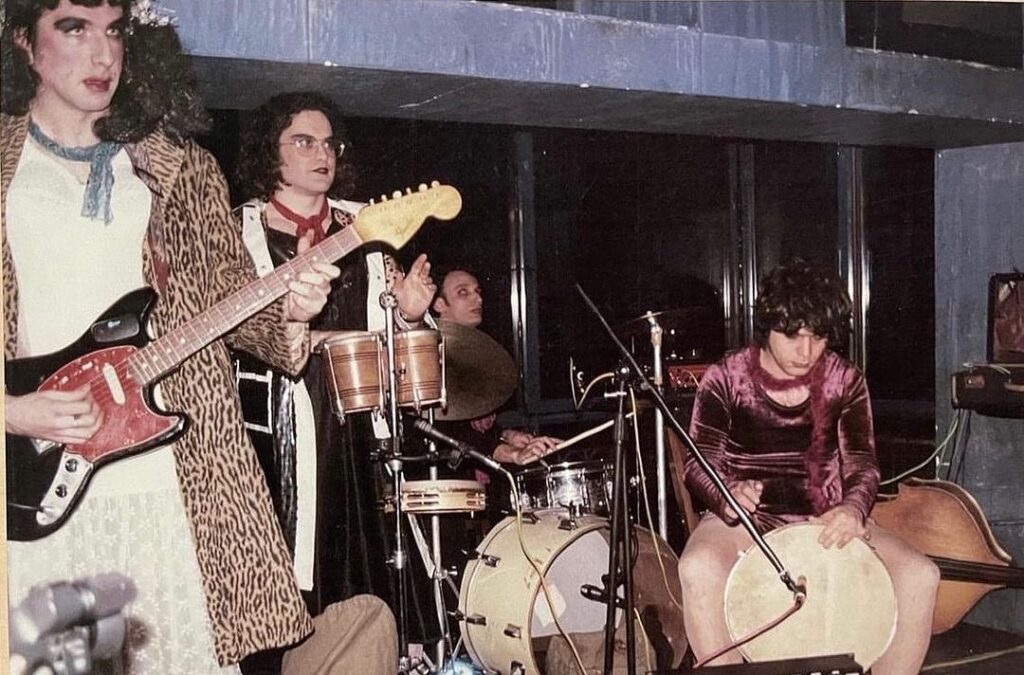

Mhmm. Yes, Zen was not my first band. My first band was Mavi Güneş 69, which I formed in 1969 when I was five. I formed many bands since then. The overall vision with Zen was that we were improvising. I really liked improvising very much. So, I had some guys I played with. Then I went to university and continued jamming with them. I started making some compositions and writing lyrics. With Zen, we began playing these songs. After some time, I gave up composing with Zen, and we started completely improvising. Our vision with Zen was that the best music for us was improvised music, and the best lyrics were improvised lyrics. So we continued with this approach.

The record was recorded live in Istanbul’s Bakırköy Psychiatric Hospital for an audience of patients, doctors and visitors, this exceptional recording offers. How did you get the idea for it and what was the reaction?

The record was recorded live in Istanbul’s Bakırköy psychiatric hospital for an audience of patients, doctors, and visitors. This exceptional recording offers…

Yes, it was a surprise for us. We were playing and also directing a club—like, we were the musical directors of a club in Taksim, at the center of Istanbul, called Peyote. There was some great music made there, and Fatih Akin captured this, you know? Many of his guests in his documentary called Crossing the Bridge were the musicians playing at this club. He would come to this club. Two nurses from Bakırköy psychiatric hospital also came to the club, and they said they wanted to meet us. They wanted us to make some music for the patients in Bakırköy, believing the patients would enjoy our music very much. So that was the reason—that was the idea, you know? They also said it would be a free concert. They had no budget; they could arrange a bus and some food, but that was it. The idea was so nice that we said yes.

But then we had to go to the hospital and live there, like eat with the nurses and talk with the doctors, the librarian, you know, and take photos. In the end, we did a concert with total improvisation, but we prepared beforehand. The audience’s reaction was mixed, you know? The nurses told us not to go too dark or too deep because maybe some patients couldn’t handle that easily, as we could. We started playing, and some of the patients wanted to leave directly. Some quit, like five minutes later or ten minutes later. Others were really into it, and some were really, really deep into it, and we couldn’t look at them, you know, because their reactions were too intense for us. There were also some guests—some people who got tickets, doctors, nurses—but it was mostly for the patients, and I really can’t forget it. We filmed it. We have a video of it that I found after all these years, and I remember the doctors and nurses telling us, “Please don’t shoot the patients.” I remember that. Yes.

You released several records with Zen, would love it if you could talk about ‘Suda Balık’, ‘Derya’, ‘Tanbul’… Would you say your albums always had a concept behind it or was it done in complete improvisation?

Well, it was done in complete improvisation, but the album concept, I think, for me, revolved around some instruments of mine. For instance, in ‘Suda Balık,’ I kind of invented or built a guitar I called a few-fretted guitar. This few-fretted guitar had only five frets, and then it was fretless. I had two versions of it: one was an acoustic version, and the second one was an electric version. So, I played ‘Suda Balık’ with these two guitars, and that was the music coming from those two instruments.

Then somehow, Thurston Moore from Sonic Youth heard this album, and he kind of connected us. He said he wanted to release this album. We told him, “Oh, we already released this album, so we can do a new one.” So we recorded Derya, which consisted mostly of collective improvisations done with electric guitar and sometimes electric sounds.

With electric saz, I had a really strong, very revolutionary electric sound that was never done before. You know? Electric saz features a very revolutionary and experimental electric sound that I still cannot hear anywhere else.

Can you elaborate how BaBa ZuLa originally formed? Do you see it as a continuation of what you did with Zen?

Yes, yes. With Zen, we were always doing collective improvisation, but I wanted to concentrate on Turkish music, Turkish scales, and Turkish rhythms. It’s the Adhan, but I still think I can do it.

The guys from Zen thought that this could be a barricade because they felt we were doing free improvisation. My wish to use Turkish scales and Turkish rhythms was something limiting for them. So, I had this itch in me with Zen; I really wanted to play in a specific direction, and some other guys didn’t want that.

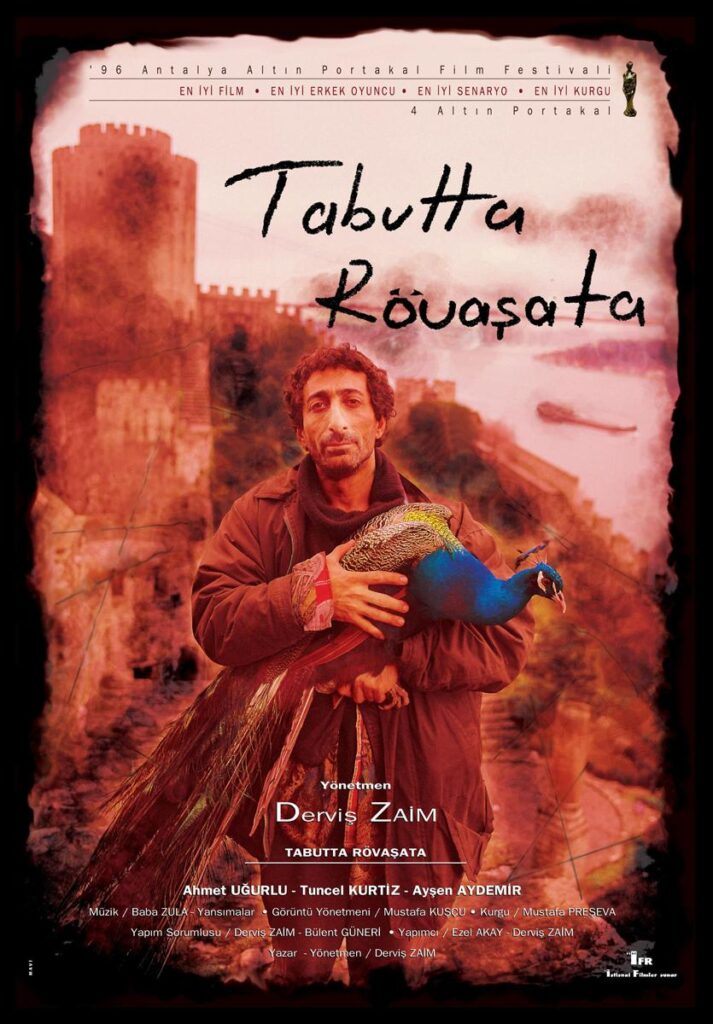

Then I had a director friend at Bosphorus University named Derviş Zaim. Darvish wanted the band Zen to make music for a movie. We watched the movie with the members of Zen, and some members didn’t like the movie. But I, along with two other guys, including Levent, loved the movie. The movie’s name was Summersault in a Coffin. I said we were going to make music for this movie, and we would call ourselves another band.

After making music for this movie, I named the band BaBa ZuLa. With this band, we could do what was in my mind musically, and I was very happy.

There must be a story behind the band’s name?

Yes, generally, there is a story behind so many things. For instance, there is a story behind every song. I think you’re asking about the story behind the band’s name, Zen. Yes, we had no name, but we were playing. Then we had to give a concert, and for that concert, we needed a name. I was at a bar talking with a girlfriend of mine, and she said if she had a girl child, she would name her Zen. I asked, “What does it mean?” At that time, I didn’t know anything about Zen Buddhism, so “Zen” was a strange word for me.

She said, “I’m so sorry. Zen means woman in Persian.” Also, if you use this word as a suffix after an instrument, it means the one who plays. I really liked this idea because “Zen woman” was a great name for me. I loved this idea. I’ve always had strong women in my life, and I adore women. I think it’s a man’s world, and women should rule the world. So, I named the band Zen.

What was it like working on a film soundtrack? How did you get to participate in ‘Tabutta Rövaşata’?

Well, starting from a very young age, I was going to theaters and rehearsals, listening to how music affected a performance. My family were also founders of the Turkish Cinematheque. So, from a very young age, I was really into the art of movies. Also, with Zen, while we were rehearsing, we were accompanying family movies that were shot in 8mm or super 8. We would show them, making loops and loops of family movies, and we also showed some slides, accompanying those movies.

With Zen, we started doing these things at concerts, and we really liked that so much. You know, even when you were playing at the ugliest salon or concert hall, we could change the atmosphere of that hall and make it a very nice place—a fantastic place to make music. So, working on the film soundtrack was very good for us. We also did many soundtracks, mostly for short films, with them. So, we knew what it was.

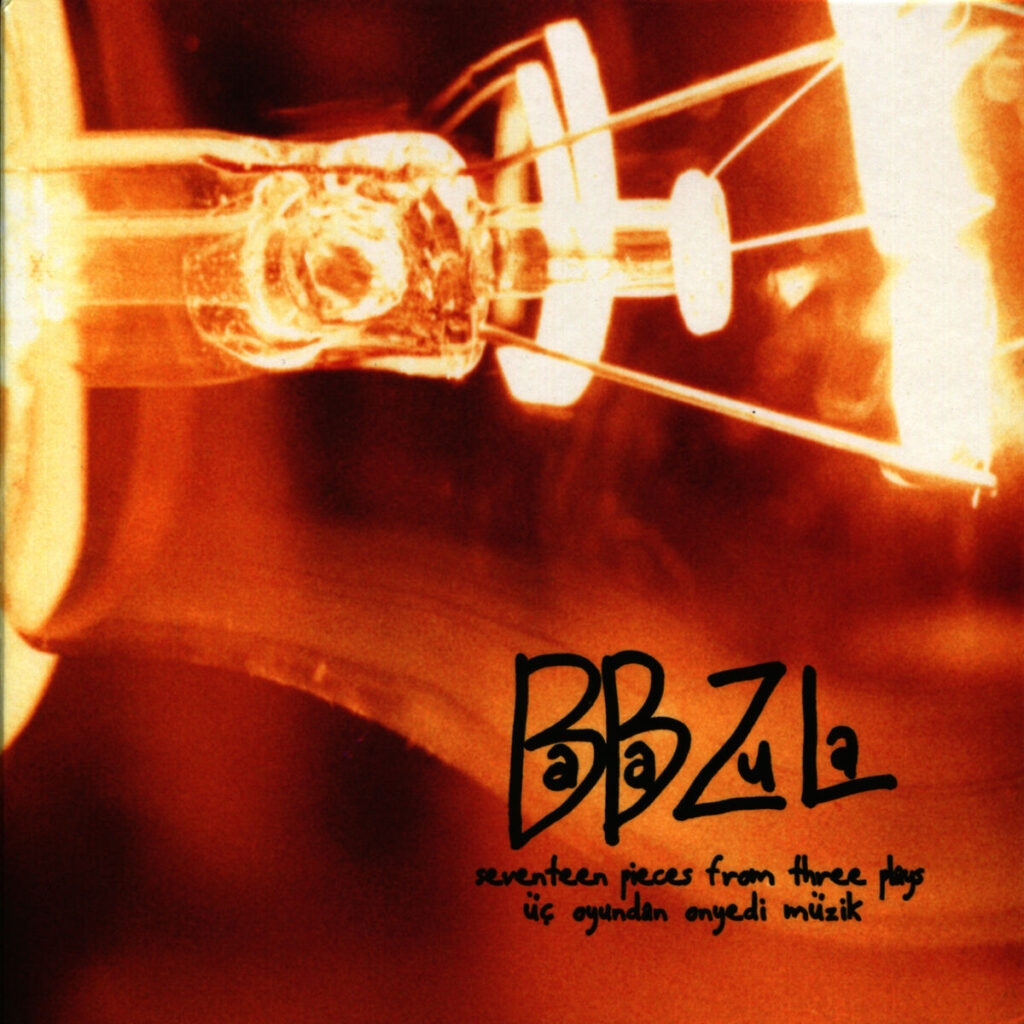

What are some of the strongest memories from working on ‘Üç Oyundan Onyedi Müzik’?

Well, after Baba Zula was born, there was a period from 1996 to 2000 where we survived as Zen and BaBa ZuLa. But Zen was playing more live, while Baba Zula became famous because of the movie soundtracks. We received many offers from other movies and theaters. So, this second album of BaBa ZuLa consisted of music we did for three theater plays.

I remember we did a version of ‘The Little Prince’ for children, and all the actors were mostly from the state theater. They were very, very against our music. They really didn’t accept our music, and they didn’t like our music, except for three actors—I really remember that. And very interestingly, those three actors became very famous, while the rest did not. Also, people from the theater thought the music we did could scare the children. But we were lucky because the director liked us and insisted that we continue making the music. And we did it. So, many strong memories—I can’t talk until morning, you know.

Just another one: One guest on a track called ‘Erotica’ was Ralph Carney. We had a half Native American, half Scottish American contrabass player whose name was Bill. We were listening to Tom Waits, and I said, “Oh, this saxophone guy, I think, is my favorite sax player alive.” Bill said, “Well, I know him. He plays with Tom Waits.” He said he could introduce us.

So, I said, “I want to give you a present, and I want to give it to him.” I got a 45 from a Turkish clarinet player, Mustafa Kandıralı, and gave it to him. Later, Bill told me this story. He said he went to San Francisco and called Ralph to meet. When they met, he gave him this 45. Ralph was shocked because he said, “Oh, I cannot believe it. Today, I went to a Chinese bazaar in Chinatown and bought a silver Turkish clarinet. And from Istanbul, here is a present for me, a 45 from a Turkish clarinet player.” Then, he came to Istanbul, and we had two concerts with him and made some recordings. I can go on, but let’s go to other questions.

How did the collaboration with Mad Professor come about?

Oh, yes. We did an album—’Psychebelly Dance Music’ dance music recordings—and we gave it to Doublemoon. The guys from Doublemoon said, “Oh, this is a very dubby album. Let’s get some guy from the dub world and let him mix your album.” So, this was kind of a dream come true. We started thinking about who could do this. We thought about Lee Perry, but in the end, because King Tubby was dead, we said Perry could be a bad dream or something—he could do something weird and mess up the situation. Then we considered the Scientist, and also Mad Professor.

When we listened to the ‘No Protection’ album by the Mad Professor, we said, “This guy can really make something good even better and change it.” So, we contacted the Mad Professor, and then it was a friendship for life.

What about Dirtmusic? Was it born in Ljubljana, Slovenia with Chris Eckman?

I don’t know how Dirtmusic was born, really. Hugo Race And Chris Eckman were doing some kind of African Mali music, which I kind of liked. I said, “Oh, let’s play together.” They came to Istanbul to play together, and the album was going so well that they asked me if I could be one of the producers of the album we were recording. I said yes.

After the album finished, they said, “The chemistry among us is so good that we want to continue that music with you.” I said yes to that, too. So, it still continues, and we are doing recordings for our next album, which is going to be released in 2025. We did the recordings in Istanbul at my studio, but the vocals are being recorded all around the world now.

Can you share some further words about your ‘Hayvan Gibi’?

Wow. We were touring with BaBa ZuLa before the pandemic like mad, you know, sometimes doing around 100 gigs per year.

And we really wanted to capture this live sound in our albums. Then, there was this option brought to us by our manager, Ahmetcan Taşdemir. His idea was, in between touring, to get like two days off and record at a studio that was built in the old cassette room of the largest record printing factory in Europe.

This studio was so good that it was built by architects with sound design in their heads and very good engineers. They were collecting many analog equipment from all around the world. But the most important thing was that they believed that when you changed media, you lost some very crucial elements in music. So if you were going to press a vinyl, your master should be a vinyl. And, for instance, even if you recorded analog onto reel-to-reel tape, when you changed it into vinyl, you’d lose many crucial elements. So we were going to use masters for vinyl, and we went to the Netherlands to make this recording.

Because it was in between the tour and the concerts, I think the band feeling was really very strong, and we could make a recording of BaBa ZuLa resembling a concert situation. So this was our last album. We finished recording our latest album, and it’s going to be released in November 2024 from Glitterbeat Records. Its name is ‘İstanbul Sokakları’ (The Streets of Istanbul), and it has eight tracks—four of them are taksims, which are instrumental improvisations coming from Turkish tradition, and four are songs, three of which have lyrics and one is instrumental.

When it comes to saz, who are some of the players that influenced your style?

I think there are literally hundreds of saz players. I love so many of them, and we have to divide them into electric and acoustic styles, and then into Divan and Jura. I can talk until morning answering this question.

About my first influences, they were, I think, live players. They were Ruhi Su. I followed Ruhi Su until he died; this was a span of around 30 years for me. Then, Ashık Kısani was my biggest influence because he was also a showman and a very charismatic figure of the sixties and a close friend of my family. Also, Ashik Mahzuni, another saz player from a younger generation, was mostly a composer—not a very interesting master of the instrument, but mostly a composer. I was influenced by the songs he composed with his saz, as well as from all the Ashık records. The first one could be Ashik Feyzullah Çinar, but I was also influenced by Murat Çobanoğlu and Ashik Veysel. Not an Ashık, but I also really like Neşet Ertaş.

And, of course, Arif Sağ. I think I like the older guys more, like Orhan Gencebay, although politically I hate him. He’s a very good electric saz player, and Arif Sağ is also a great master. And, I don’t know…

So many players like Özer Şenay and I, and 3 Hürel, double like guitars, electric saz instruments. It was very interesting. Ohannes Kemer from Bariş Manço, Kurtalan Express, and of course, Cahit Berkay from Moğollar. Yes, I think these are some of the saz players.

I was always influenced by them, but I think I was also influenced by guitar players as well. My biggest influence could be Jimi Hendrix, I think. Apart from him, there are so many popular and unpopular guitar players that influenced me, like Santana. For instance one from the unpopular side, Pete Cosey. I was very influenced by Pete Cosey.

What else currently occupies your life?

Yes, well, I think slowing down everything occupies my life. Slowing down the way we cook, slowing down the tempo of concerts, and slowing down life—I really enjoy that. Also, family life and children. I bought a Greek bouzouki from Athens, from a luthier family called Shahkirian. They immigrated from Anatolia, Izmir, to Piraeus.

For four generations, they have been making bouzoukis and other instruments. This Greek bouzouki, I really, really love and play it so much. It occupies my life. Then, I have a new sampler I need to master, but I made a promise that I would finish this interview first, and then I would master this. So I was waiting.

The first thing is I think we will finish the BaBa ZuLa album. It’s kind of finished, but it needs mastering, and also it needs the cover to be completed. The cover is almost finished, but we have to finalize it and the mastering, plus do some videos for the album. This is very important for me.

Then we have a plan for a Zen documentary. This is very exciting! I am checking Zen videos, and we have, I don’t know, around 200 concerts that are videotaped and recorded.

So I think we have more than enough material for the movie, and this is going to be very exciting. Another exciting piece of news is that director Fatih Akın’s Crossing the Bridge has been upgraded to 4K, and it has been acquired by MUBI, which I think is the best platform in the world and is run by Turkish people. So, this movie, in which we are featured and which introduced us internationally in 2004 after 20 years, is being re-released. I think this will be another very good move for BaBa ZuLa. I’m looking forward to this.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

Oh, my memory is sometimes too dark. I have to think about this. My favorite albums lately? I don’t know. But one of my favorite albums is an instrumental Cuban album that’s recorded with only two instruments, and its name is ‘Comet.’ These instruments have thousands of strings and are tuned to only a fraction of notes.

So the music in it is very spacey. I really like it. Although it’s acoustic, it sounds kind of like electronics. This might be my favorite album, but lately, I don’t know.

Thank you.

Thank you, Klemen. Say hi to your family and to your little girl. I’m delighted that she is listening to BaBa ZuLa. Hope to meet you one day in person. See you. Bye-bye.

Klemen Breznikar

BaBa ZuLa Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube