Exploring The Blues Society: An Interview with Augusta Palmer

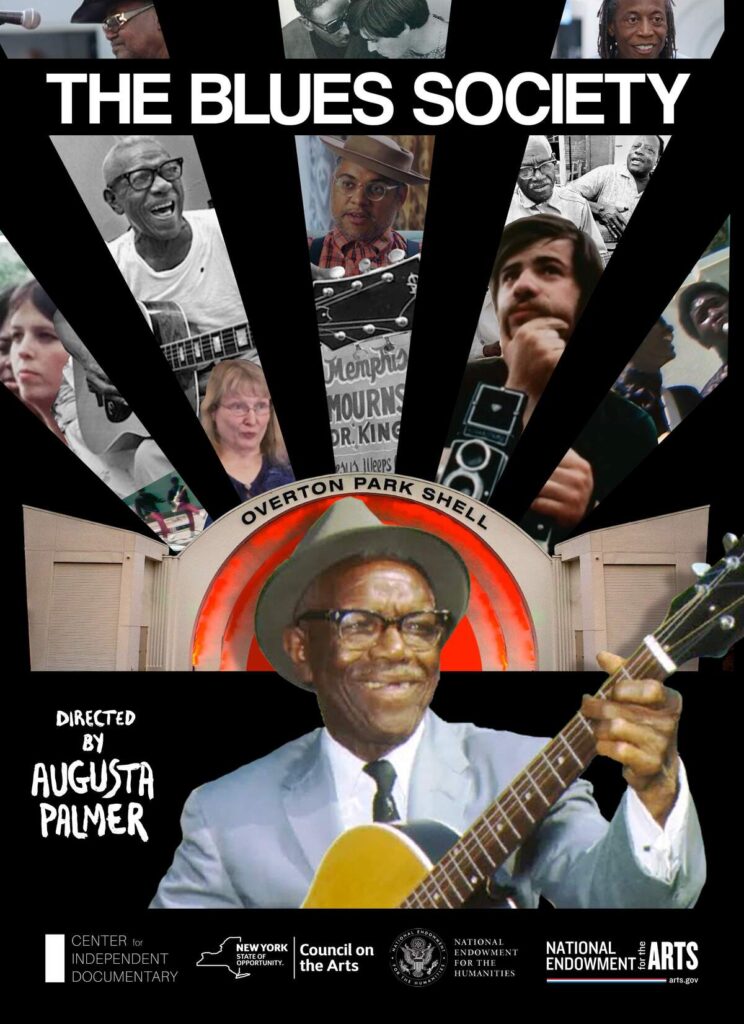

The Blues Society is a feature-length documentary that critically examines the Memphis Country Blues Festival, focusing on the intersections of race, countercultural movements of the 1960s, and the Memphis blues genre.

The film includes interviews with prominent figures from the festival, such as Nancy Jeffries and Henry Nelson, as well as archival commentary from notable commentators like Bob Palmer, voiced by Eric Roberts.

Directed by Augusta Palmer, the documentary avoids the traditional concert film format, instead exploring the narrative arc of the festival’s history and its cultural significance. The festival’s inception in 1966 is presented as an impromptu event that blossomed into a significant cultural phenomenon, culminating in a three-day festival in 1969. The documentary highlights the collaboration between black and white musicians during a pivotal moment in the civil rights era, providing a nuanced perspective on the sociopolitical climate of the time.

Augusta notes the festival’s contrasting elements, such as the presence of the Ku Klux Klan rally in the same park shortly before the event, underscoring the tensions surrounding racial dynamics in Memphis. The film chronicles the careers of blues masters like Furry Lewis and Rev. Robert Wilkins, emphasizing their contributions to the genre while illustrating their relative obscurity during the 1960s.

By showcasing the festival’s evolution, The Blues Society illustrates the cross-pollination of musical influences between the Southern blues tradition and the burgeoning counterculture of New York’s East Village. The documentary garnered critical acclaim, winning the Audience Award at the Indie Memphis festival and the Best Documentary Feature award at the Oxford Film Festival. Its theatrical runs in cities such as New York City, Memphis, and Portland further highlight its widespread appeal and the relevance of its themes.

The Blues Society engages audiences in discussions about cultural appropriation and the complexities of appreciating African American music within a historically segregated context. Ultimately, the documentary serves as both a celebration of the Memphis Country Blues Festival and a critical examination of the social and cultural forces that shaped its legacy.

“I think counterculture is really hard for a lot of people to understand now”

The Blues Society is such a personal project for you, given your father’s involvement in the original festival. How did your personal connection influence the direction and tone of the documentary?

Dr. Augusta Palmer: Both of my parents were involved in organizing the Memphis Country Blues Festival. Their involvement drew me to the subject matter, but I feel like I found a whole new family while making the film. Because my dad, Robert Palmer, was a white man who wrote a book called Deep Blues and made his name as a Blues scholar, I felt it was especially important to center the perspectives of Black Americans— including interviews with the Blues masters celebrated by the festival, festival attendees like Henry Nelson, and contemporary commentators like Jamey Hatley, Zandria Robinson, and Dom Flemons.

Could you share a moment during the making of this film where you felt an unexpected connection to the music or the history you were uncovering? How did it shape the final product?

When I first heard a recording of my mother, Mary Branton (then Mary Palmer), urging gatecrashers to put money in a hat for the Blues masters, and realized she was pregnant with me at the time, I felt intimately connected to the history. The music continues to grab me every time I see the film. This realization shaped the film by making me want to focus on the collective efforts to create the festival and the broad swath of people involved, rather than just the “great men” who often get foregrounded in history. The fact that the music continues to move me made me want to shape a narrative that allows others to feel the power of that music and to learn a bit more about the musicians like Furry Lewis and the Wilkins family, who have made such major contributions to American culture.

“What surprised me initially was how central psychedelic drugs were”

The Memphis Country Blues Festival was born out of a unique convergence of cultural and personal factors. What was the most surprising thing you learned about this convergence while making the documentary?

What surprised me initially was how central psychedelic drugs were to that moment and how much positive impact they had on a generation of spiritual seekers like my dad, Nancy Jeffries, and most of the festival organizers. Nancy said, “It was the opposite of dulling your senses; it was waking up.” The power of psychedelic drugs is something people like Michael Pollan and a lot of medical research studies talk about in the mainstream media now, but when I first thought about making the film in 2013, it seemed pretty radical.

The festival took place during a highly volatile time in American history, with the civil rights movement in full swing. How did the festival’s timing influence the narrative you chose to tell?

Well, from my point of view, the Civil Rights Movement is still ongoing. By this, I mean that structural racism still influences and limits our lives and our culture. Having said that, of course, the period from 1966 to 1970 is a very important moment in that history, and the murder of Martin Luther King is a crucial moment in the story, as well as for the city of Memphis. It was essential for me to present that moment in some of its rawness and complexity.

Your film dives into the complex relationships between the festival’s white organizers and the Black musicians they sought to celebrate. How do you think this dynamic reflects broader societal issues both then and now?

Sociologist Zandria Robinson says in the film, “I think what happens is that we were like, ‘Let’s be friends despite power dynamics because there’s not slavery anymore and so we can…’ But no. It’s a really difficult thing. There’s always a disconnect that complicates cross-racial friendships, collaborations, because that power dynamic is always sitting there in that room, in the deep context of the music, which is violence and pain and hurt.”

To me, that’s the core of the dynamic. And the question is, how do we move forward and have conversations? White people like me have to create opportunities to have conversations about that power dynamic without denying its existence. Blues music and the 1960s Blues Revival is a really good place to center that conversation because Blues is so powerful and so universally appealing in the way it conveys both joy and suffering, yet it was created by Black Americans in very specific historical contexts. And they deserve the credit and ownership of this most American of genres. But white people and white-owned industries made huge amounts of money off the music and exploited its creators.

This is a spoiler for some, but the fact that John Wilkins died of COVID almost always elicits an audible intake of breath or even a groan from audiences. I think we need to talk much more about how different the pandemic was for Black and brown people than it was for white people. That, along with police violence and economic inequality, is a place where we clearly see how deeply racism still impacts and even governs American society.

You’ve mentioned that The Blues Society explores themes of race, counterculture, and appropriation. How do you hope modern audiences will engage with these themes, especially in today’s sociopolitical climate?

I constructed the film to raise questions, to hopefully make audiences see how constructed history is and how we really have to decide who and what to believe rather than relying on a fictional all-seeing narrative. I think counterculture is really hard for a lot of people to understand now because we have a million countercultures and no real monoculture.

I’ve loved showing the film to Black and brown high school and college students, and I’ve especially loved that female-identified students seem particularly taken with the music and the history. That’s so great because these 1960s events were quite male-centered (even though women played powerful roles in making them happen), so I hope that people who don’t know the music get turned on to it. Those audiences asked great questions about appropriation. I’ve also had great conversations with older, predominantly white audiences who are asking similar questions about their own generation’s role in appropriation.

I’m raising money now to do more outreach with the film, which will involve both more conversations and, if we raise enough, paying musicians to perform for audiences, too.

“The blues is about having nothing and creating joy, putting the joy and the survival on record.”

The blues has often been described as a genre rooted in both pain and resilience. How did you approach capturing this duality in your documentary?

I think the musicians did that for me. But interviewees Jamey Hatley and Henry Nelson also really brought those points out. Henry speaks about the Blues as “private, belonging to a culture” but also makes it clear that the music tells stories that hurt. Jamey Hatley says near the end of the film, “The blues is about having nothing and creating joy, putting the joy and the survival on record. We need that right now. People need that.”

She said that to me in 2016, but it’s just as true six years later.

Furry Lewis, Nathan Beauregard, and Rev. Robert Wilkins were central figures in the festival. What do you think was the most significant contribution they made to the blues, and how did the festival help to preserve their legacies?

Furry Lewis, Nathan Beauregard, and Rev. Robert Wilkins each made their own unique contributions to Blues music. Furry had this incredibly percussive yet also lyrical sound and was an incredibly charismatic performer for many decades. Rev. Robert Wilkins, as a Blues player and then a Gospel player, had this gorgeous guitar sound and an incredibly infectious beat that continues to propel a lot of rock music. Nathan Beauregard had this high lonesome vocal quality and what Zeke Johnson, a Memphis musician I interviewed, called “an acoustic electric sound” on guitar—meaning that though he played an electric guitar, he used it to translate and amplify an acoustic style of playing.

The festival certainly increased their profiles and helped preserve their legacies. Wilkins had been at the Newport Folk Festival, and Furry Lewis went on to open for the Rolling Stones, record a TV special with Leon Russell, and appear in a Burt Reynolds film. Coverage of the festival in Rolling Stone Magazine and elsewhere certainly added to these players’ legacies.

Nathan Beauregard, however, was buried in an unmarked grave in 1970, which was very shocking to me, as was the fact that he was in his 70s rather than over 100, as festival organizers said. On the other hand, it’s only due to the festivals that we know about him and his music. And I worked with the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund to find out where he was buried and was there to dedicate a monument, so his grave in Ashland, MS is now marked.

The documentary highlights a fascinating intersection of different generations and musical styles. How do you think the festival helped to bridge the gap between traditional blues and the emerging counterculture of the 1960s?

Nancy Jeffries says in the film, “The idea for the festival was to pay homage to the originators of this musical style that was influencing such a large movement in rock music at the time.” I think the festival was a place where rock musicians played alongside and in support of blues artists. The music they created was a hybrid, syncretic music that wove together traditional and new forms.

Your creative process seems very much like a musical improvisation, finding elements and piecing them together over time. Can you share how this improvisational approach influenced the final edit of The Blues Society?

I started another film of mine, The Hand of Fatima, with a quote from Islamic scholar Henry Corbin that says, “the past remains present to the future, in which the future is already present to the past, just as the notes of a musical phrase, though played successively, nevertheless all persist together in the present and thus form a phrase.” I’m a pretty visual person, so I think more about my films as a collage that happens over time—both the time it takes to view the film and the much longer time it took to make it. And for history films, there’s the idea that the present defines how you see history, and seeing that history may define what happens in the future. When someone asks me to answer an either/or question, I tend to give a both/and answer. So my process is by turns analytical and intuitive, scholarly and impulsive.

You’ve worked with archival footage, interviews, and historical research. What was the most challenging aspect of bringing these elements together to tell a cohesive and engaging story?

Just finding the balance between elements. When do we need to see a speaker’s face? When do we need to hear more music or be immersed in archival footage? How long should the Bar-Kays dance the Sideways Pony? How can I shape the tip of the iceberg that’s visible in the film to reflect some of the shapes below the surface? Those are exciting challenges. I hope folks are watching a lot more of the Bar-Kays, however, since this year is their 60th anniversary as a band!

If you could go back in time to the first Memphis Country Blues Festival, what would you want to witness firsthand? And how would that moment influence your work?

I’d like to see what my mom looked like when she spoke to the crowd in 1969. No one captured that. I’d also really like to see firsthand how the festivals were different each year. I found no footage or still photographs of 1966, so I’d love to see what that first year was like. I had to really imagine it from reading about it. I’m sure seeing it would have shifted the film in some ways… Even hearing an audio recording helped me understand (and portray) how the event shifted over those few short years from a hippie happening to a multimedia event.

The Blues Society has resonated with diverse audiences, winning awards and acclaim. How do you see this film contributing to the ongoing conversation about race, music, and cultural appropriation?

Well, I really liked what the Oxford Film Festival jury said about the film: “The Blues Society is an evocative reintroduction to the most important contributions of Memphis Country Blues to the fabric of American music. Using priceless archival footage and engaging interviews to provide depth and context, it transports the audience to 1960s Memphis, reflecting on the blurred lines between appreciation and appropriation and examining how we weigh intent against impact at the crossroads of race, culture, and economics.” I hope the film continues to do that for some folks.

You’ve collaborated with the Music Maker Relief Foundation and engaged with high school students as part of this project. What impact do you hope these outreach efforts will have on future generations?

I feel it’s a bit overblown to think of this small film’s impact on “future generations.” I’m hoping to collaborate with Music Maker on bringing musicians they support to play for audiences. To me, that kind of cross-generational exchange is the greatest thing the film could do. I hope it puts people into conversations that span racial, cultural, and generational boundaries. I love showing the film to teens and 20-somethings because they have completely different takes on the history but are, at the same time, more in touch with that crazy energy than I am. I’m as old as my grandparents were in the 1960s, so I’m a bit slower than they are.

Lastly, in a more lighthearted vein—if you could choose any blues musician, past or present, to perform a soundtrack for your life, who would it be and why?

You know, I don’t think I can pick just one. Memphis Minnie was so sexy and tough. I love her song ‘Fingerprint Blues,’ when she talks about her gun and her switchblade knife. Skip James’ music just takes me to another plane, and I love it when I’m feeling sad. Rising Stars Fife and Drum Band and the whole tradition of Otha Turner that Sharde Thomas inherited really transports me, too. The ethereal fife and the massive drum are an intense combination. I love CeDell Davis because he was such an original. His music is so resilient and tough yet shaped by pain. Furry Lewis makes me laugh and cry at the same time. The Wilkins family, from Rev. Robert to his son John and now the Wilkins Sisters band (Rev. Robert’s granddaughters and great-granddaughter), makes me want to move, to get up and dance.

What’s next for you?

I’m excited to be developing a new project about the science, culture, and history of color. How and why do we see the color red, or the color blue, or the color gray, or the color brown? And how does that visual experience give us a feeling? Those are the questions my new film—or it could be a series—will ask.

Klemen Breznikar

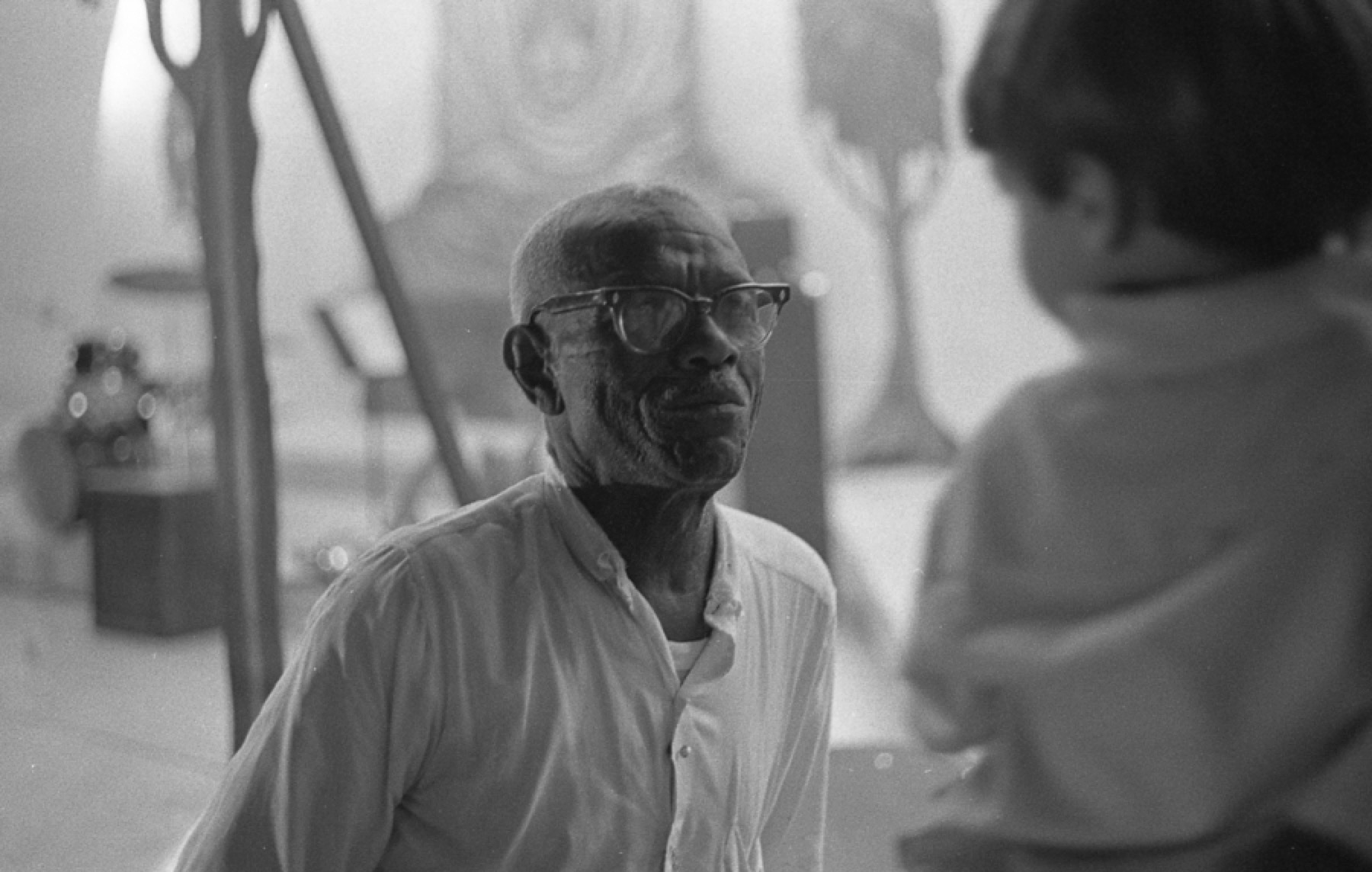

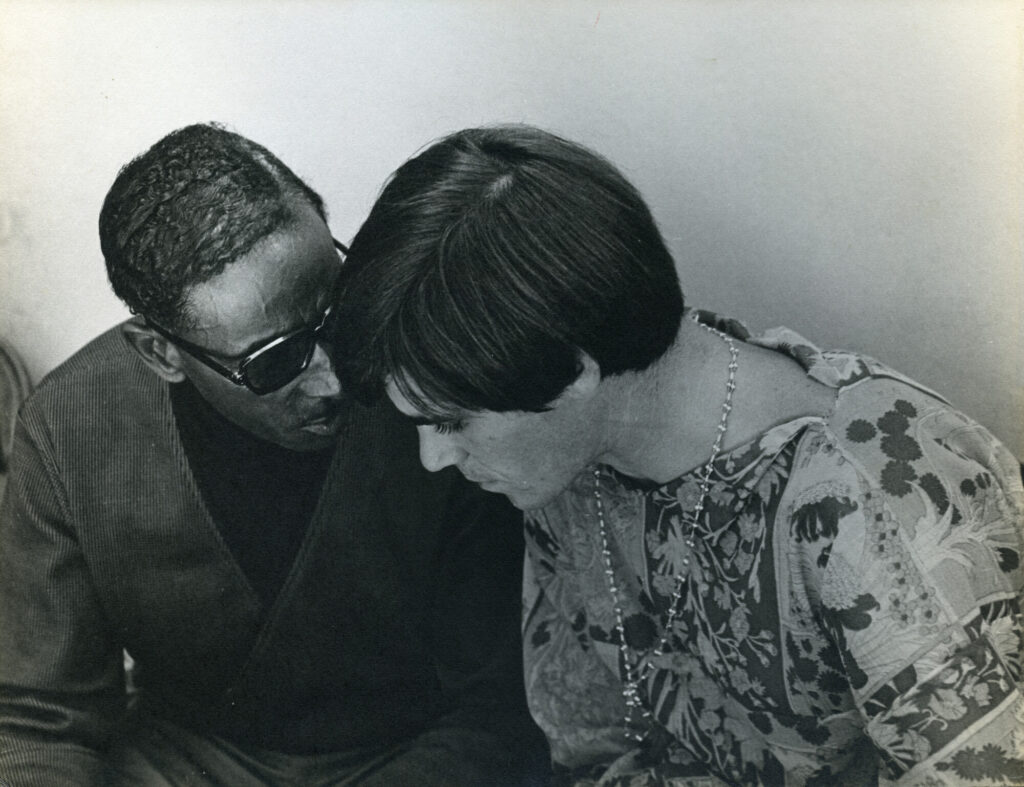

Headline photo: Furry Lewis and Glade | Photo credit: Douglas Cupples

The Blues Society Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter