Gordon Bok | Interview | “I’ve spent much time among maritime people, absorbing stories and experiences”

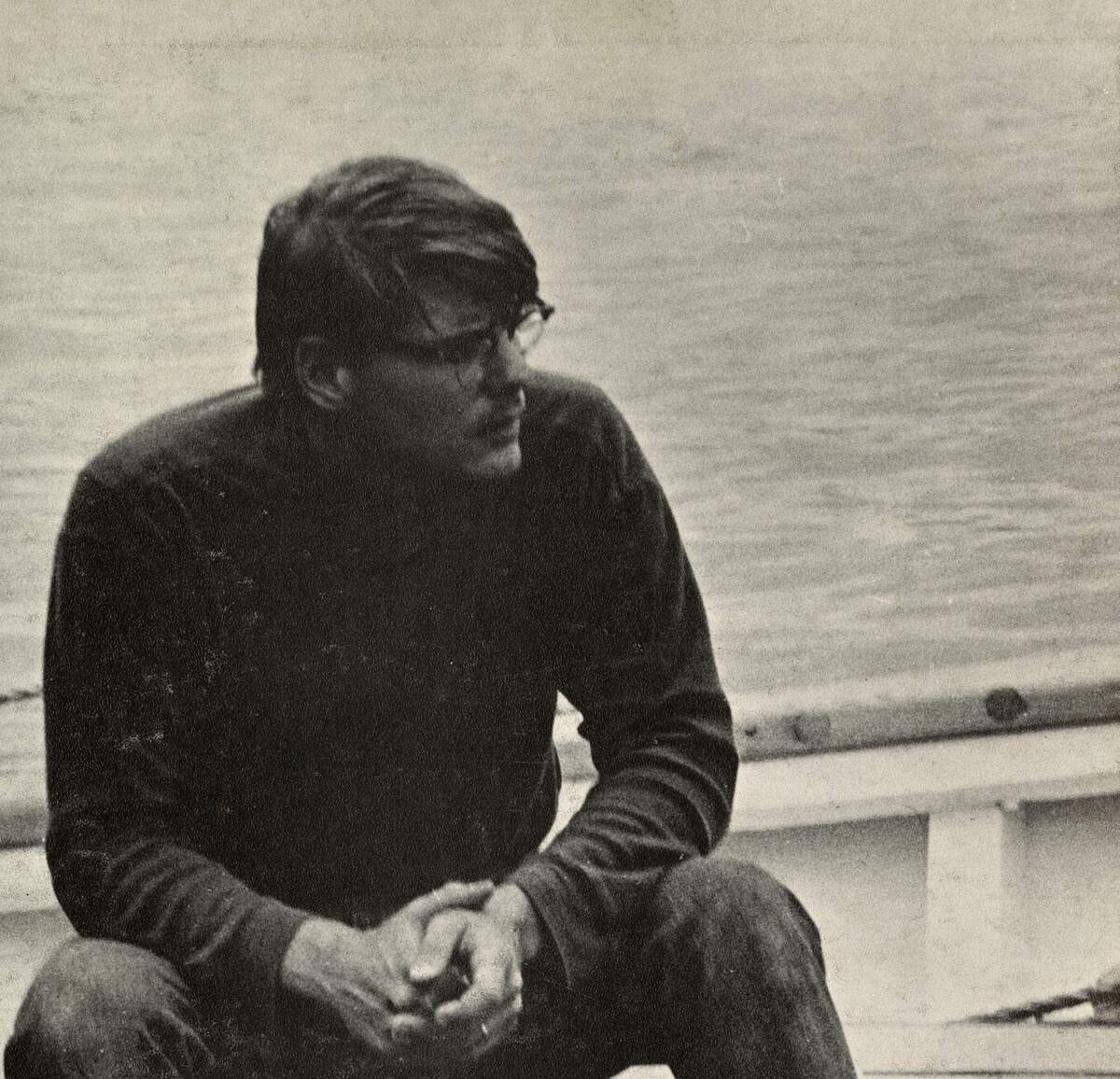

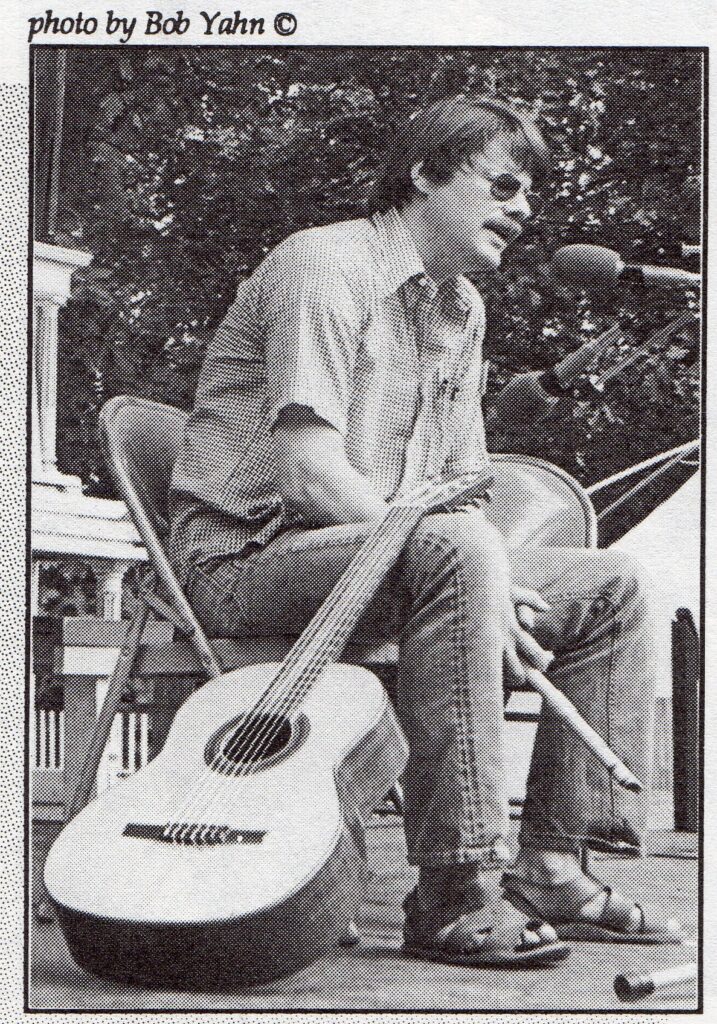

Gordon Bok is a distinguished American folk musician and songwriter born in Pennsylvania in 1939, who has spent much of his life immersed in the maritime culture of Maine.

At the age of three, his family relocated to Maine, where his father worked in a shipyard building wooden vessels for the government during WWII. This environment shaped Bok’s childhood, with shipwrights and machinists as his heroes and the post-war shipyard as his playground. His mother’s family fostered a love for music, learning songs during their travels, ensuring that there was never a lack of music in his home.

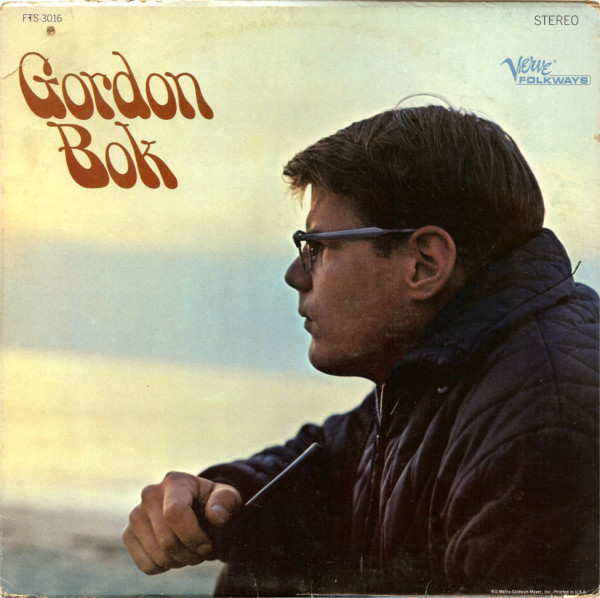

Bok’s early jobs on local boats ignited his passion for music, as he absorbed the sounds and traditions from various backgrounds. His guitar playing was influenced by a diverse array of artists, including Leadbelly, Les Paul, and Laurindo Almeida, as well as the natural sounds around him. In the 1960s, while continuing to work on boats in the summer, he ventured into cities like New York and Philadelphia during winter, where he met Noel Paul Stookey, who encouraged him to record his first album for Verve Records.

Throughout his career, Bok has collaborated with notable musicians, including a decades-long partnership with Ann Mayo Muir and Ed Trickett. He has toured extensively, sharing his music across North America, the United Kingdom, and beyond, while also engaging with cultural communities, such as Kalmyk Mongolian immigrants in Philadelphia. In 1969, he was the original first mate on the sloop Clearwater, where he began a fruitful relationship with Sandy and Caroline Paton, the owners of Folk Legacy Records.

Bok founded Timberhead Music in 1986, which has since produced 18 albums, including his own and those of other artists. His work has been honored with numerous accolades, including a Blue Ribbon Award from the American Film Festival and a Lifetime Achievement Award from Rutgers University. Currently, Bok continues to create music, art, and design, recently releasing his latest album, ‘Windcalling,’ in December 2023. His legacy is now preserved in the Smithsonian Institute’s Folkways Recordings, ensuring that his contributions to folk music and maritime heritage will live on.

“I have to trust that there will always be people who need the beauty and wisdom in the old songs”

Can you recall some childhood memories and discuss how your upbringing influenced your passion for music?

Gordon Bok: Some holiday gatherings of my mother’s people—after the food was done, and the toasts were sung—the singing moved into the living room where the instruments were, and it kept going there as the room darkened from afternoon to evening. I remember mostly the singing, the blend of family voices in slow solo ballads or harmony, and the fact that they didn’t need light to keep on singing. They played guitars in various forms, the odd banjo, harmonica, whistle, or piano. They knew most of the songs Burl Ives had collected.

What initially attracted you to folk music, and were there any specific artists or songs that inspired you in your early years?

Quite a few recording artists, like John Jacob Niles and Josh White. One aunt of mine lived in the same apartment building as Huddie Ledbetter, and another came back from Italy with Piemontesi songs and Russian songs she sang with a seven-string guitar. One learned Hebridean songs from another cousin. They walked in the woods singing, they sang while they washed dishes. They didn’t make a big deal of it. I couldn’t sing in tune, but no one ever told me not to sing in that family.

Your journey from being a sailor to a full-time musician is quite unique. Can you describe the transition process?

It was never as black-and-white as that. I worked on people’s boats in summer when I was going to school and took a lot of other jobs in winter after that. I never “followed the boats south,” as the climate didn’t seem to agree with me.

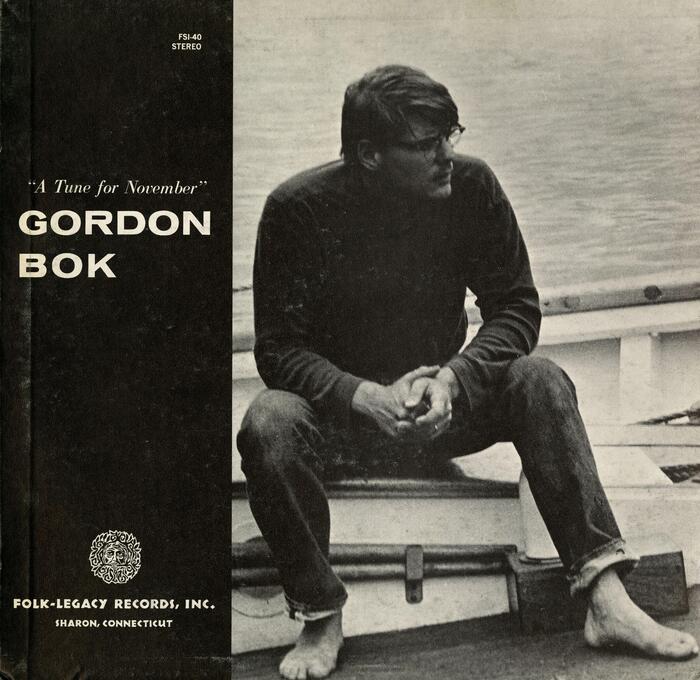

Your debut album was released in 1965. What inspired this album, and how did it feel to share your music with a wider audience for the first time?

In the late 50s and early 60s, I drifted into playing concerts with the encouragement of professional musicians like Esther Halpern, and Noel Paul Stookey convinced me to make my first album, which he produced himself for the Verve label. After the album came out, I didn’t have any real contact with the record company (Verve); I just went on about my business on the boats and played concerts that came in. It never occurred to me to flog albums at those concerts; my head just wasn’t in that place in those days.

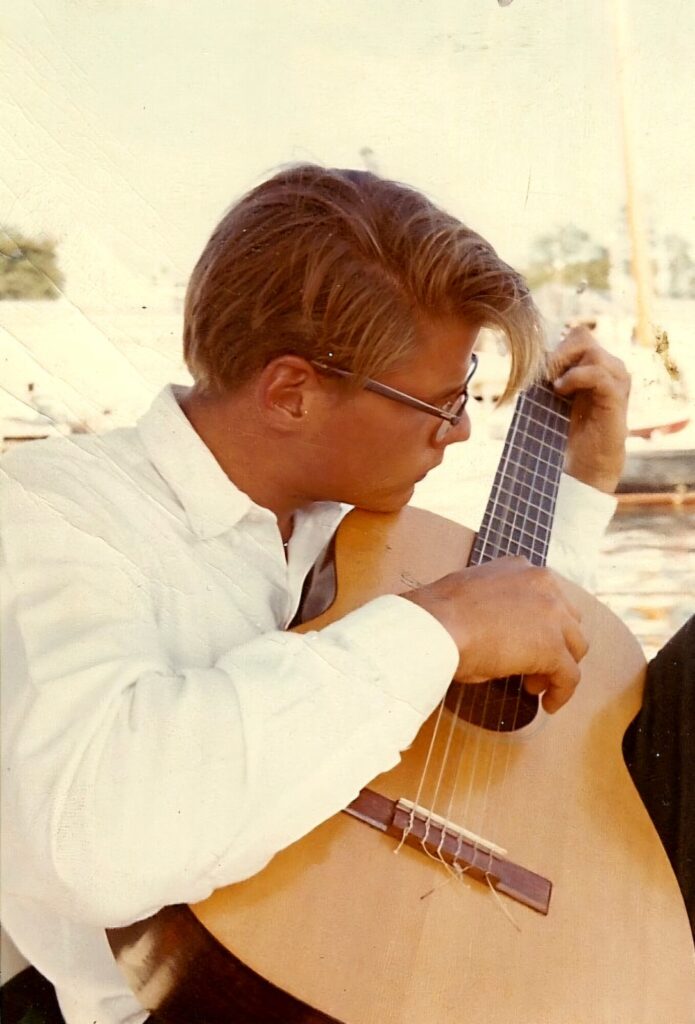

Your fingerpicking style is distinctive. Can you share insights into your creative process and how you developed this technique?

It’s more a compendium of styles than a conscious work-up of a single technique. I accompanied fiddlers playing for contradances when those tunes were going extinct in New England, and I then incorporated the melodies into the accompaniment when there wasn’t a fiddler handy. I played Mongolian tunes with Kalmyks dancing to their own music in Philadelphia, and those musicians taught me songs from different lands their people had passed through. Friends brought me music from South America they had picked up from working there; I just kept my ears open and my fingers busy, trying to accommodate it all. I learned some composed classical pieces (not very accurately) all by ear, not from the written page. I still read and write music—slowly.

Could you discuss the creative process behind ‘A Tune for November’? Any memorable moments from recording it?

‘A Tune for November’… As far as I can remember, some of that was generated by a real situation, but then—as I’m told some writers develop novels—the characters start acting on their own, and the writer just “records” them. Looking at that song now, though, it seems to fall into the “predictive” rather than the descriptive category. I don’t remember much of my creative process, as I seem to be in a kind of altered mental state when I get into it.

Your connection to the sea and maritime culture is evident in your music. How do you see this aspect of your identity reflected in your songs, and what draws you to explore these themes?

I’ve spent a lot of my time among “maritime” people, absorbed stories, and drawn from my own experiences as well as from many other people’s experiences: stories they’ve told me, poetry they’ve written, and things I’ve experienced because of the music I’ve made or gathered and passed on.

When composing, do you draw inspiration primarily from personal experiences, historical accounts, or a combination of both?

A large part of the music I sing has been given or sent to me over the decades, simply because people have heard what I sing and want to share something they find important.

I have to trust that there will always be people who need the beauty and wisdom in the old songs, who simply find their awe refreshed in the mystery in them. I know there will always be those who need to make music, from their own or from their people’s experiences. Who knows what “folk” means today… for half a century, people have been painting that label on whatever they’re trying to sell. But there’s an intense electric connection when someone like Cathal McConnell sits you down in a kitchen and actually teaches you his version of an old song that was given to him in the same way. I liken that experience to what it might be like to climb down into the Grand Canyon on your own two feet (in your own sneakers).

Throughout your career, you’ve collaborated with various artists. How do these collaborations influence your creative process, and are there any that stand out as particularly memorable or impactful?

I love working with other people, whether it’s designing things (or music) or building things (including music). I’m all too familiar with my own “creative process,” and I love the clarity and energy that others bring to the things we can cobble together. And they don’t need to be musicians, or woodworkers, or professionals: If they love what they’re doing, I love working with them.

Your live performances are known for their intimacy and emotional depth. How do you connect with your audience during performances?

I don’t know how we connect, but we do. It’s not because of any great effort on my part. I think that it’s just the gift of the music. And while I suspect the music takes each of us to a different place, it seems to be a place where we need to go.

Collaboration is a recurring theme in your career. How do you believe it enhances your music and message?

Ed Trickett and Ann Muir were a great gift to my life. We consider each song a life—and we loved growing into it together, going through a door deeper into the center of the human experience. Those who share music with you help you go farther in, or show you their paths.

You’re involved in maritime heritage organizations and environmental activism. How does your music intersect with these causes, and what role do you believe artists play in raising awareness and effecting change?

Change comes from those who can “think outside the box,” and artists are associated with that thinking. “Heritage,” at best, nourishes what’s good about the past and helps us to blunder through this world in more useful ways.

Looking back on your discography, are there any albums or songs that hold a particularly special place in your heart? What makes them stand out?

When I’m reminded of songs I’ve recorded, they feel like friends, and I want to hug them again. I have learned and sung these songs because I needed them at the time to help me understand—or just live—my life. So you could say they’re all special.

What legacy do you hope to leave behind as a folk musician, particularly regarding your impact on Maine’s cultural heritage?

It would be nice to think I’ve made or brought to light some songs that have been useful to other people.

Klemen Breznikar

Photos: Gordon Bok personal archive

Gordon Bok Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp