Revisiting the French Noise Scene of the 90s: Insights from the Upcoming ‘France Noise 90’ Compilation

‘France Noise 90,’ an eagerly anticipated compilation curated by Yves-Marie Mahé and set for release by Jelodanti Records on October 22nd, provides an insightful exploration of the often underappreciated French noise scene of the 1990s.

Mahé’s project not only preserves the raw energy and DIY spirit of this dynamic musical period but also aims to reshape the perception of French experimental music on a global scale. Unlike the more mainstream recognition of American, British, or Japanese noise scenes, French bands of this era often organized their own concerts, fostering a strong sense of community and collaboration between local and international acts. The compilation includes previously unreleased tracks and rare recordings, revealing the unique atmospheres and soundscapes that defined the French scene. Yves-Marie Mahé’s dedication to both music and visual arts is evident in the compilation’s striking design, crafted by Clara Djian and Nicolas Leto of the Jelodanti label, reflecting the intersection of these creative fields in 90s France. Mahé’s homage to Steve Albini, a key influence on many of the featured bands, underscores the connection between the French scene and the broader world of noise and experimental music. By bringing this eclectic selection of artists into the spotlight, ‘France Noise 90’ provides a vital narrative for those curious about the intersection of noise, post-rock, and avant-garde art. This release serves not only as a historical document but as an invitation for a new generation to explore and engage with France’s rich experimental heritage.

“It was the music of militant youth who believed in revolution”

Can you share with us a bit about your journey in the world of music and art? How did you initially get involved in the underground music scene in France, and what led you to curate this particular compilation?

Yves-Marie Mahé: As a teenager, I started studying cinema (with my friend Arnaud Larhant). At the same time, we were discovering anarchism and punk. In France, in the second half of the 80s, there was an influential second-generation punk movement called “rock alternatif.” This movement was highly political (with bands like Bérurier Noir) but also very present in the media. When I entered the professional world of cinema, I was quickly disappointed by the hierarchical atmosphere. So, I turned to experimental cinema, closer to DIY punk. In 1995, Arnaud Larhant and I started going to Les Instants Chavirés in the Paris suburb of Montreuil. Although initially a jazz club, the venue hosted the French and international experimental rock scene. We soon began filming the concerts. The result is the self-produced documentary Le rock expérimental des Instants Chavirés (finalized in 2018), which can be seen here:

What drew you to noise music and the broader experimental rock scene in France during the 90s? Was there a specific moment or band that sparked your interest?

As an experimental director (I’ve made over 70 short films) and a punk fan, I have to like the experimental punk scene. At the same time as I was listening to the current 90’s scene, I was discovering the French underground movement born between May ’68 and the emergence of punk. It was the music of militant youth who believed in revolution. These artists are not disconnected from reality. They found coherence between their ideals and their music through self-production. Underground French music in the 70s was diverse: it included progressive music, but also crazy songs like Brigitte Fontaine and Albert Marcoeur, free rock like Red Noise and Camizole, and the beginnings of electronic music with Richard Pinhas and Heldon. It was also a period of technical evolution, with the advent of the synthesizer and the drum machine. It also saw the emergence of the “Saravah,” “BYG,” “Futura,” “Disjuncta,” and “Cobra” labels. I also made a radio documentary on the subject, please see here.

What was the primary motivation behind compiling France Noise 90? Was there a particular message or atmosphere you wanted to convey with this collection?

After a descent into the cellar, I came across some demos I’d received when organizing concerts. I rediscovered the raw versions of certain tracks that had been smoothed out for studio recording. After talking to Clara and Nicolas from the Jelodanti label, I quickly realized that we all wanted to revive this movement by releasing previously unreleased material or rarities. Diving back into the memory of their musical practice can, for artists, rekindle the desire to get back into it. In any case, it enabled us to meet up again and exchange ideas, not only about the past but also about current projects. The two sides of the vinyl have been designed differently: an A side with rock bands and a more experimental B side with solo projects.

Can you walk us through the process of selecting the bands and tracks featured on this compilation? How did you decide which bands and tracks best represented the French noise scene of the 90s?

Many of the major French bands (Ulan Bator, Hint, Deity Guns, Bästard) had already re-released their own material. So, we chose to focus on lesser-known but equally deserving bands. The compilation is not intended to be exhaustive—other very good bands are absent. I chose bands that were interacting with each other: Copywrong & Copyright (who have members in common), Cornice, King Biscuit appear together on 45 splits. Philippe Thiphaine can be found in Heliogabale, in his solo projects (The Crooner Of Doom, This Side Of Jordan), and he recorded the Flaming Demonics live. Frédéric D’Hérouville plays in Gordz and also appears with his solo project Ratiopharm. Franck Lantignac (Kivalo Dolgozo) played with Nicolas Marmin (Osaka Bondage) in the band Permanent Fatal Error (not included on the compilation). Éric Pougeau (Flaming Demonics) was living at Vincent Muel’s (Kivalo Dolgozo). Prohibition, which has its own label Prohibited, has produced many bands.

Did you have any personal connections or friendships with the artists featured on this compilation? How did those relationships influence the final selection of tracks?

I know half the members of the selected groups. It was very exciting to reconnect with people with whom we’d sometimes lost touch over the last two decades. With other musicians, we had remained close. Olivier Remy of Hole Process was my brother-in-law. Thierry Müller did the music for my documentary Jeune cinéma, released last year.

Were there any technical challenges in sourcing and remastering the tracks, particularly given that some were recorded on older formats like K7 tapes? How did you address these challenges?

Most of the bands, although amateurs, have carefully kept the tapes, sometimes for over 30 years. Each band has digitized the tracks themselves. With DIY musicians, it’s always very simple. I find the same thing in the experimental film circuit. With more professional circles, it can be more complicated or uninteresting (with only discussions about money).

The tragic fate of Kivalo Dolgozo’s members is quite poignant. How did their story impact your decision to include ‘Remember’ on this compilation? What do you think makes their music stand out despite their brief existence?

I discovered Kivalo Dolgozo very recently. The cinema programmer Bertrand Grimault (Monoquini) played me their only 45 at his home in Bordeaux. I immediately loved it. Their music is very original. When I listen to it, I don’t think of any particular reference. Gérald Clédel (bassist), Sami Rahal (singer-guitarist), and Vincent Muel (producer) all died prematurely. The only survivor, drummer Franck Lantignac, went on to play with Voodoo Muzak and Ulan Bator. Franck made me listen to all of Kivalo Dolgozo’s songs. It’s an incredible band. If a label is interested in releasing a complete set, please contact me, and I’ll pass the info on to Franck.

Flaming Demonics had a very short but intense run. How do you feel their wild, chaotic performances and raw energy are captured in ‘Cross My Mind (Live)’? What legacy do you think they left behind in the French noise scene?

Flaming Demonics were renowned for their wild concerts during their 2-year existence. Eric Pougeau (guitar and vocals) has become a recognized contemporary artist. Through family and religion, he tackles death, violence, and morality with insolence and humor. Flaming Demonics can be seen in my documentary online Les Établissements Phonographiques de L’Est (with English subtitles):

Cornice’s use of self-made instruments is fascinating. How do you think their DIY approach and unique sound contribute to the overall atmosphere of the compilation? What do you know about the band’s creative process?

Cornice tinkered with their instruments themselves. The selected song is based mainly on strings with no drums or distortion. In 2022, the tape label Sun In Yr Head released previously unreleased material by Cornice.

Prohibition was a significant presence in the noise-rock scene with their extensive touring and recordings. What do you think makes ‘Hell No Rush’ representative of their influence on the French noise scene?

The idea was not to feature the bands’ best-known songs, but rather to include previously unreleased or rare tracks. The Prohibition track was previously unreleased and followed well after the track by Nik Kern (Sootcycl), who was a friend of theirs. It was through Prohibition that I found Nik’s contact. I met Nik one evening in 1996 at Arnaud Larhant’s, and I have never seen her again; we argued that night. I loved her demo.

Osaka Bondage stands out with its blend of ambient, industrial, and noise elements. Can you elaborate on how their evolving sound and experimental approach reflect the broader trends in the 90s French noise scene?

Initially, Osaka Bondage moved towards very dark, creeping worlds, using small noise-making machines and tinkering with various types of vintage electronic materials. In a second period, the band moved towards post-rock. It seems to me that they were a bit apart from the rock scene. They were also appreciated by an older generation close to the 70s Futura label. They accompanied poet Michel Bulteau (Mahogany Brain) for recordings on France Culture radio. It was Nicolas Marmin of Osaka Bondage who first told me about the Nurse With Wound list. Nicolas continues to introduce new bands via the legendary Radio Libertaire program Epsilonia, which he co-hosts.

“This compilation presents their first projects, the matrix of everything they did afterward”

Many of the bands featured had relatively short-lived careers or were part of side projects. How did these ephemeral aspects of their existence contribute to the energy and rawness captured in their music? Were there any bands that you wanted to include but couldn’t, and if so, why?

Many of these musicians are still active. This compilation presents their first projects, the matrix of everything they did afterward. Purr (from the label Prohibited) tried to find the master of their K7 demo, but it wasn’t possible. Sister Iodine was also supposed to offer a track, but that didn’t materialize. With Kim from Witches Valley, we couldn’t agree on the choice of track. These are 3 bands I like a lot but that we couldn’t fit into the compilation.

How do you see the French noise scene of the 90s in the broader context of global experimental music? What do you think makes it distinct from other scenes, such as those in the US, UK, or Japan?

Bands often organized concerts themselves, and French and international bands played together. For example, I discovered Sister Iodine and Deity Guns opening for Sonic Youth (who had produced the Deity Guns album) in 1992. It seems to me that French rock is discredited abroad. One of the intents of the compilation was to show that there are original bands in France too. Rita Mitsouko or Les Négresses Vertes were exported abroad in the 80s because their music was very personal.

The compilation seems to be as much about preserving the memory of these bands as it is about introducing them to new audiences. What do you hope listeners, especially those unfamiliar with this scene, take away from this compilation?

I hope this will inspire them to smash their smartphones, look at each other, and make a lot of noise together.

You mention that the passion behind this project is not just about music but also the visual arts. Can you expand on how the visual art scene in France during the 90s intersected with the music scene, and how this relationship is reflected in the compilation?

The relationship between visual arts and music is reflected in the cover of this compilation, through the work of Clara Djian and Nicolas Leto of the Jelodanti label, who are also artists. Like them, the 90s noise musicians were interested in many different fields. Most of these bands were discovered through fanzines. Some magazines, such as Hello Happy Taxpayers or Ortie, had impressive graphic work. These can be downloaded from the Fanzinothèque website.

The compilation is dedicated to Steve Albini. Could you explain the significance of Albini’s influence on the French noise scene and on this compilation in particular?

Steve Albini was seen as the reference for many musicians. Heliogabale recorded ‘The Full Mind Is Alone The Clear’ in Chicago with Albini in 1997. Fred D’Hérouville of Gordz and the RuminanCe label wrote to me that Albini’s death was like a wall collapsing in his house. He had worked with him for a few days in Chicago in 2003 (for an album by the duo Chevreuil). For Fred, Albini, in addition to his major contribution to music and sound, was a person with a great sense of humor and, above all, faithful to his ideas. I always enjoy listening to the first Big Black as much as the latest Shellac. In one Shellac song, Steve Albini sings, over tense music, that people say of a woman that she’s crazy. When Albini screams that he thinks she’s all right, the music explodes. I think it’s the most beautiful piece about denial as an absolute form of resilience.

Are there any future projects or compilations you’re working on that continue in the vein of ‘France Noise 90’? What’s next for you in terms of music or art projects?

These months, I’m more involved in film-related activities. With Local Films, the producer of the documentary Jeune cinéma, we’re preparing a project on 70s French crime novelist Jean-Patrick Manchette. His stories are violent explorations of the human condition and French society. Manchette was politically to the left, and his writing reflects this through his analysis of social positions and culture. I’m also co-programming the Festival of Different and Experimental Cinemas in Paris.

Looking back on the compilation now, is there anything you would have done differently? Any particular tracks or bands you wish had been included or presented differently?

The compilation seems perfect to me. It’s exactly the record I’d like to listen to, with the added bonus of substantial graphic design. And it’s great to collaborate with Clara and Nicolas.

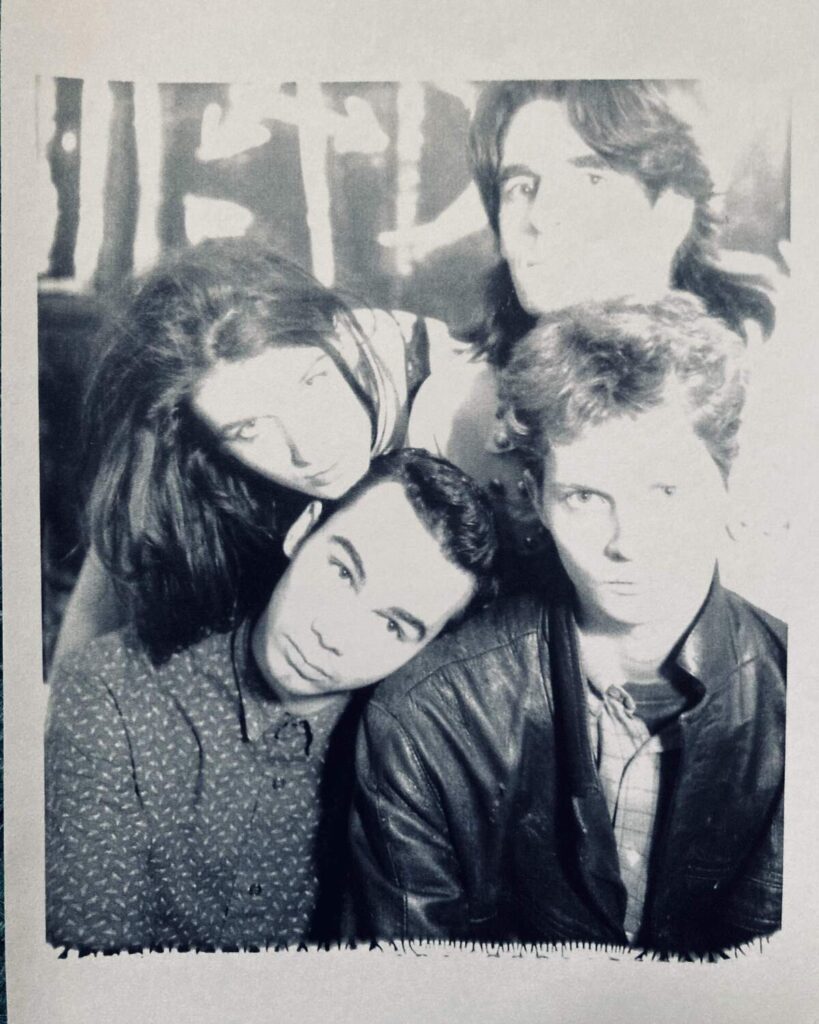

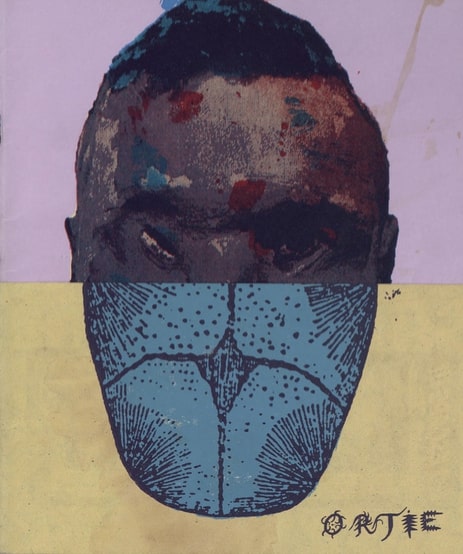

Headline photo: Flaming Demonics | Photo de Philippe Levy

Jelodanti Records Official Website / Bandcamp / YouTube