SUN | Interview | Uncovering the Hidden Gem of German Jazz Rock/Prog

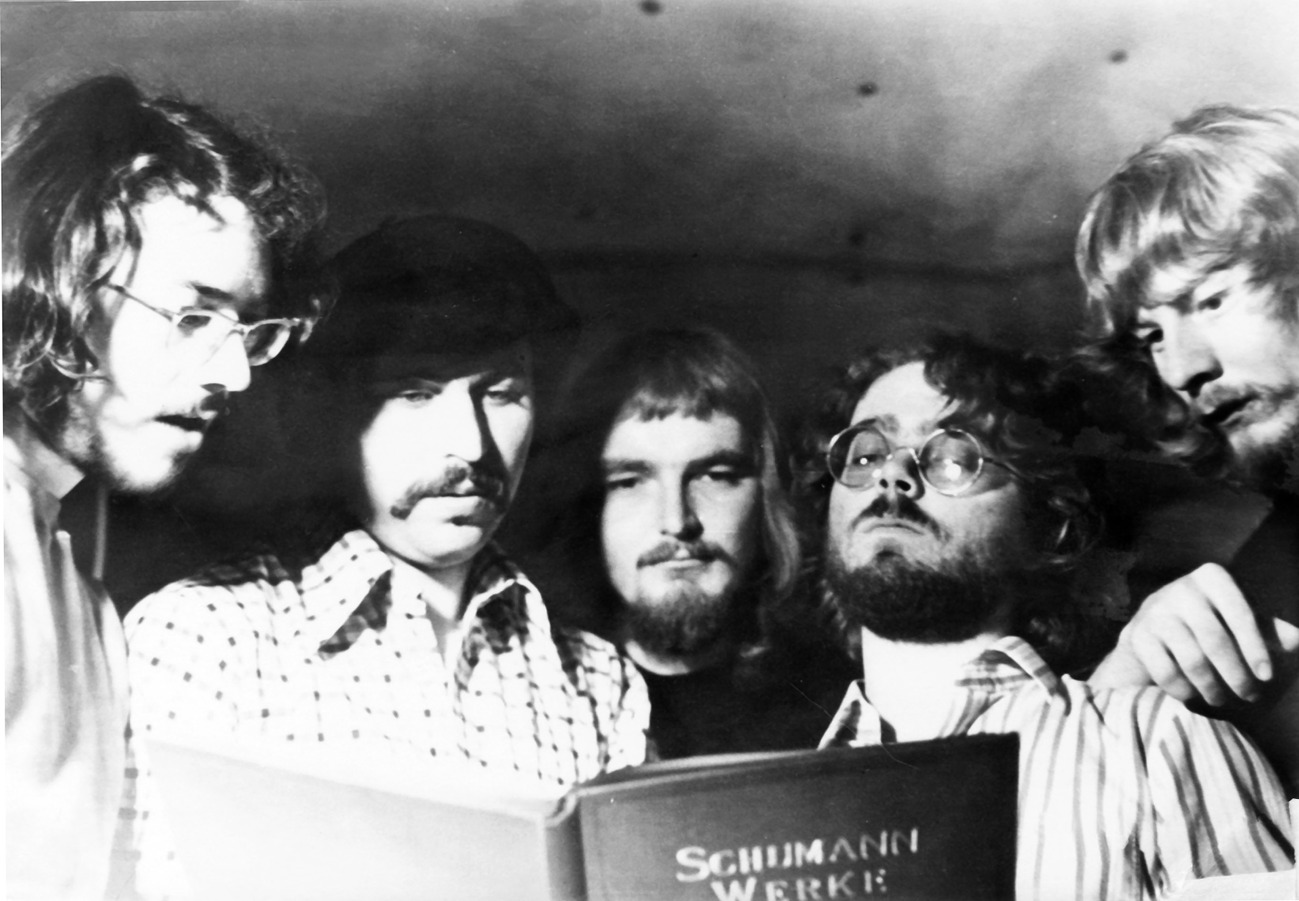

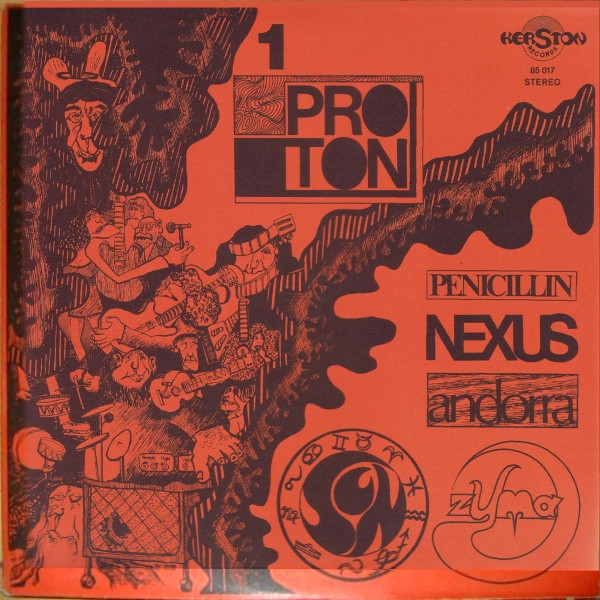

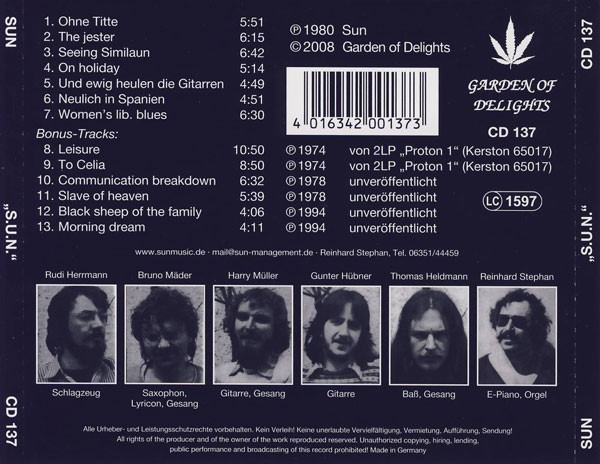

SUN was a band from southwest Germany near Mannheim that was featured on the ‘Proton’ compilation by the Kerston label in 1974 and later managed to self-release an intriguing jazz rock album with many hints to progressive groups from that time.

After their contribution to the compilation, the band reappeared in 1980 with a self-released album that, despite lacking any real commercial success, showcased a richness in musical ideas. Tracks like ‘Ohne Titte’ offer a fiery introduction to the band’s formidable musicianship, while ‘The Jester’ leans into progressive territory. However, it was their later work that provided even more insight into their creative evolution. The bonus tracks on the CD reissue by Garden of Delights are a treasure trove for fans, showcasing the band’s late 70s experiments as well as 1994 reworkings that, despite their age, sound as fresh as ever.

“Fast licks and complex melodies could be played with astonishing precision.”

Could you share some stories from your early years? Where did you grow up, and how did that environment shape your experiences? How was life in post-WWII Germany for you?

Gunter Hübner: I was born in 1956 into a not particularly musical family in a small town in the southwest of Germany, Grünstadt, Pfalz (Palatinate). I had my first musical experiences in primary school, where I learned to play the Hohner Melodica. But playing football (soccer) was much more interesting, and the melodica soon disappeared into the cupboard. Two or three years later, our grammar school teacher made a very generous offer to give me and a friend free violin lessons. My mum urged me to try it, and I was given a ¾ violin. Unfortunately, the teacher died very suddenly; I hope it wasn’t because of my terrible violin endeavors.

When I was just 14, our “gang” of teenagers wanted to play football one afternoon, but since it was pouring with rain, we all met up at my house in my little room. A very chatty guy there said, “Come on, let’s form a band!” He pointed his fingers at each person in turn. “You guys play guitar,” he said, pointing to two brothers who had a guitar at home—the older one had even been taught a few chords by his mum. He pointed to another: “You’re going to play bass guitar,” then to the next: “You’re going to play the organ.” Finally, he turned to me and said, “You’re going to play the drums,” and finished by announcing, “I’m going to be the manager of the band.”

I’m not sure if he was serious, but the two brothers, the bass player, and I thought it was a pretty cool idea, so we got together and started our first musical sessions—without the “manager.” The two brothers could sing quite well, and I had an old tambourine that I played with two wooden cooking spoons. I asked my mum (my dad had died when I was seven) if she would buy me a drum kit for Christmas. She said, “OK, son, you’ll get one, but you have to learn to play a real musical instrument first.” Drums were not considered a real instrument at that time.

In my hometown, there was an accordion orchestra club that offered lessons in both accordion and classical guitar. I didn’t have to think long and chose guitar. I was given a small guitar, which I still have today, and after six months of playing ridiculous German folk songs, I was already more advanced than the rest of the group because I was sitting at home in front of the radio, trying to play along to rock songs. Finally, my mum relented, and I got a drum kit for Christmas from the mail-order catalog shop “Otto-Versand,” which cost a whopping 600 marks at the time.

A little later, our band bought an Echolette Klemt amplifier BS40 (40 watts!) from a dance combo in my hometown. The bass player found a Höfner Beatles bass for just 72 D-marks (!!), and we were also able to buy an electric Höfner 6-string with a very “fancy” white plastic covering.

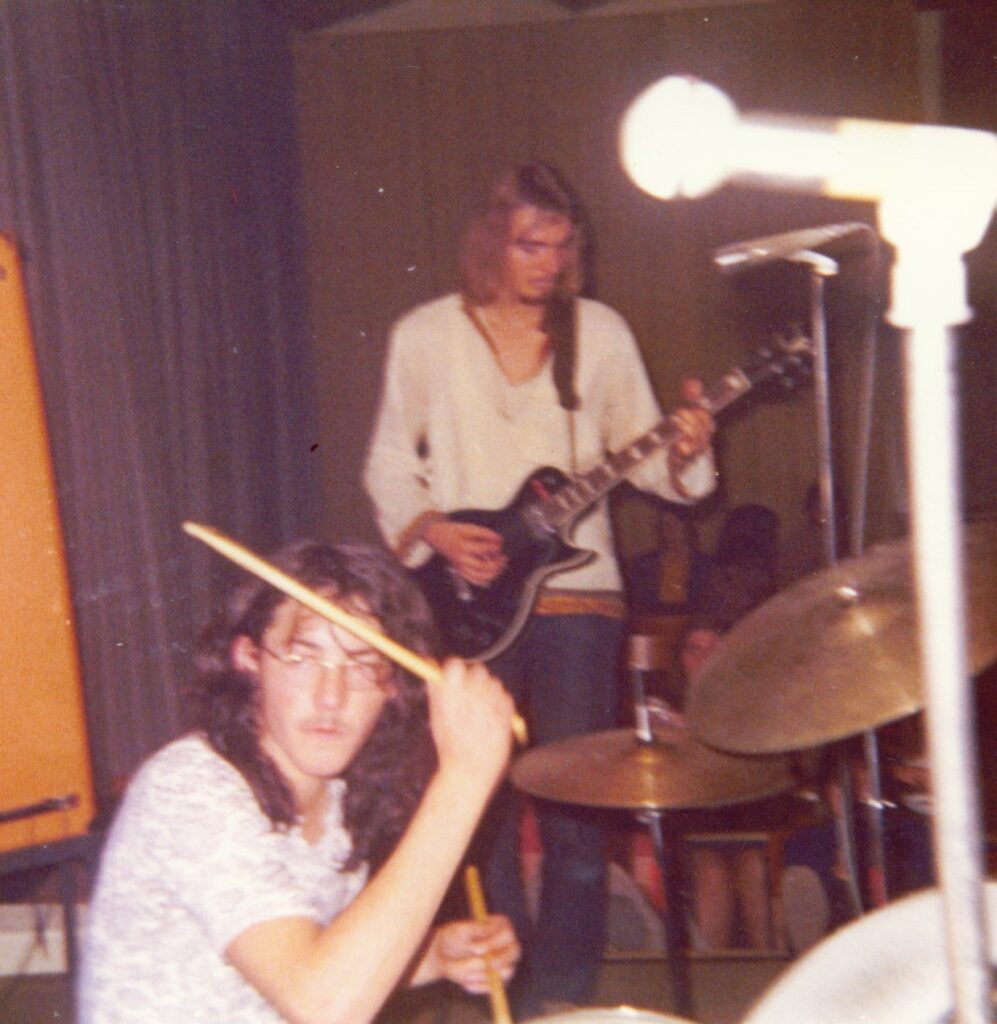

With this equipment, we played our first gig in 1971 in a Catholic Kolping clubhouse. Bass, guitar, and microphone were all connected through the same amp (!). We played simple songs by the Rolling Stones, The Who, and a German band called The Lords.

Not much later, the two brothers somehow lost interest in music, and we found a guy who was quite attractive (at least, that’s what some girls thought) and brave enough to sing, though we didn’t have a guitarist. Then the singer said, “I can do that little bit of drumming too,” and so I took over the role of guitarist—which I still play to this day. From that point on, we had some very nice gigs at school and other parties.

When I was about 16, the band broke up, and I found other musicians at my school, where we discovered our passion for jazz, jazz-rock, and fusion.

Post-WWII Germany was dominated by a very conservative mood and a booming economy. Life in a small town was quite easy at that time (1970 and on), as long as you didn’t stand out too much. But we did—our generation often protested against the establishment, continuing the tradition of the 1968 student protests. In 1968, I was still a bit too young to understand what was going on, but if you didn’t cut your hair, wore some kind of flower-power clothes under your parka, or demonstrated against the Vietnam War, the Shah of Persia, or simply for change in society, you had to be careful not to provoke conservative types. These old-fashioned types always called you a ‘Gammler’ (bum), shouting, “Get your hair cut, you bum!”

How did your passion for music first ignite? Who or what were the early influences that drew you into the world of music?

At fourteen, I was a fan of The Who. My favorite album was ‘Live at Leeds,’ which transported so much energy to me. A little later, I was blown away by the Mahavishnu Orchestra. It was around the time of the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. I was really sick with rheumatic fever and could hardly move. Immobilized, I was watching the Olympic Games on TV, lying in bed the entire day. Somehow, Mahavishnu Orchestra gave a concert during the Games in Munich that was broadcast on TV, and I was absolutely mesmerized. To this day, the album ‘Inner Mounting Flame’ is my favorite.

When did the idea of forming a band first come to life?

As mentioned above, it was shortly before my 14th birthday that my friends and I had the idea of forming a band. My first band was called The Guerrillas, which we later renamed Noch was?, in reference to the German wave in rock music. With Noch was?, we played only our own songs for the first time. We were six musicians, each contributing 15 minutes of their own compositions or arrangements. In total, our first set had 45 minutes, plus another 45 minutes in the second set. There were no breaks between the different compositions; the sets were seamless. Unfortunately, nobody really wanted to hear this epic work. That’s why we later called ourselves Omicron and focused on jazz standards.

The band later known as SUN was originally founded in 1969 as Redcoats. The founders were about 3 to 5 years older than me, and mostly, they played cover songs. Around 1972, they changed the name to Punished SUN and started playing only original compositions. I joined SUN in 1977.

Were you familiar with pioneering German bands like Tangerine Dream, Cluster, CAN, or Amon Düül II in your early days?

Yes, we knew about those bands. Our favorite German rock band, however, was Guru Guru. Personally, I preferred the jazz-rock scene. At first, we were enthusiastic about Klaus Doldinger’s Passport, and when I was sixteen, I sat in the front row of a small club where Volker Kriegel’s band was playing with Eberhard Weber, Rainer Brüninghaus, and Joe Nay. I watched Volker closely—how he played—and learning from that, I changed the way I plucked the strings, using constant up-and-down strokes to get much faster.

How would you describe the music scene in your town? Did you share the stage with any like-minded bands?

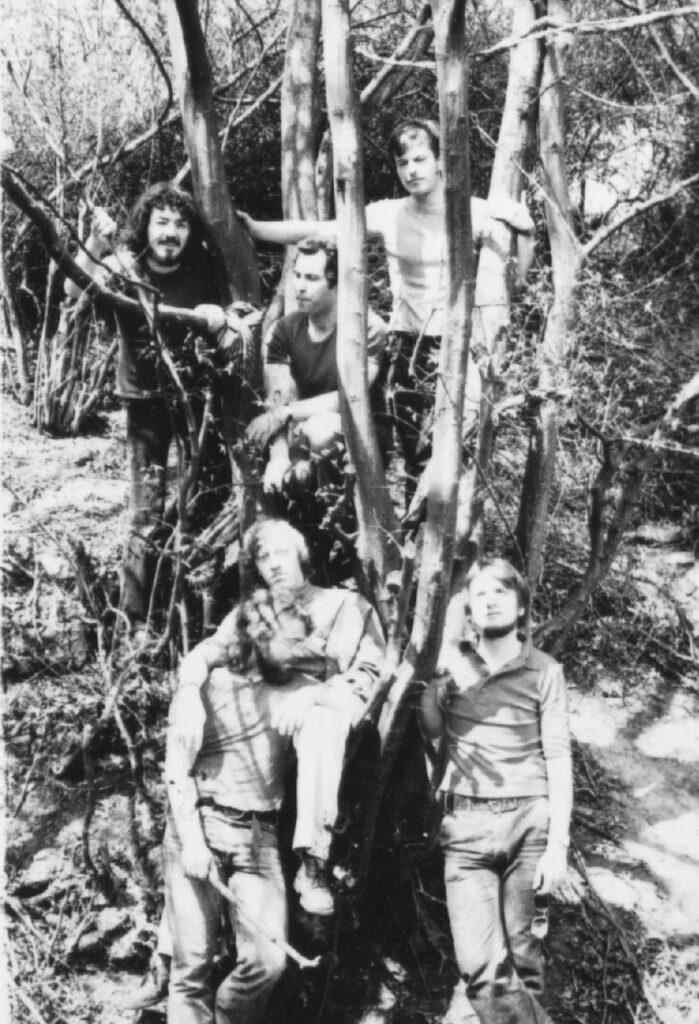

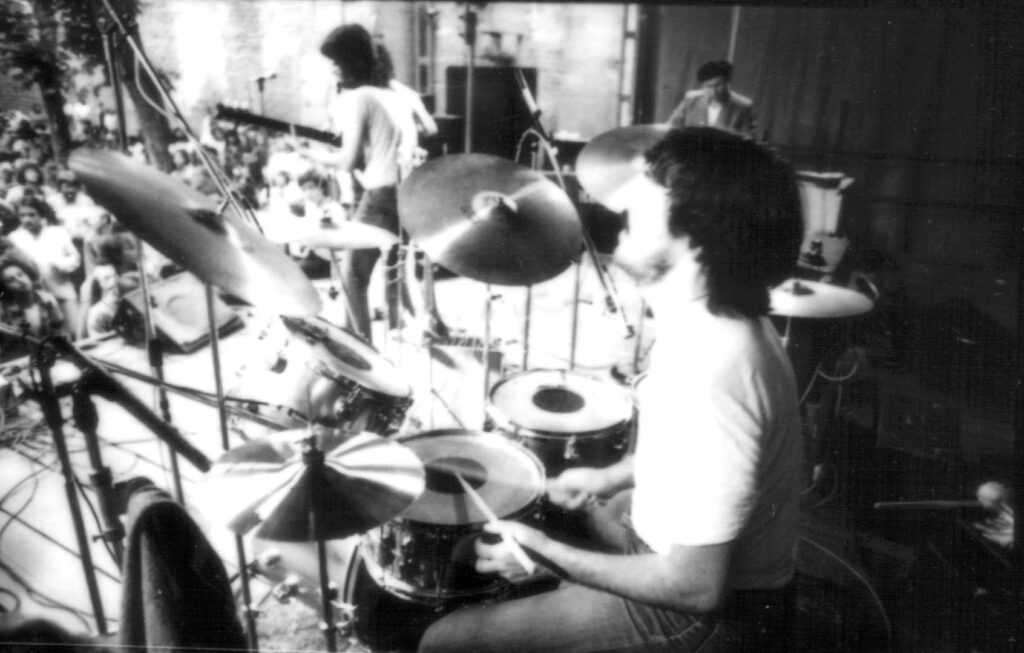

Yes, there were a few bands in the neighborhood. We initially organized small festivals with a maximum of three bands in local halls. In 1981 and 1982, we organized large outdoor festivals in an exceptionally beautiful location—a monastery ruin, the Kloster Limburg near Bad Dürkheim. About 1,000 people attended.

Reinhard “Steffen” Stephan was the main man in charge and continued to organize festivals even after SUN disbanded, especially during the period after 2007, known as the “Return of the SUN.” He was living in a small village of about two hundred people called Nackterhof, where he owned a kind of farm and organized the “Rock im Hof” festivals. Sadly, he passed away too early in 2023.

Was there a particular hangout spot where the music-loving “freaks” of the time would gather?

Yes, there were favorite places to hang out, and we hung out a lot, no doubt. In my hometown of Grünstadt, we met at least once a day at an ice cream parlor called Rialto. It was originally owned by an Italian family, but later it was run by Gerde, a very good friend and fan of SUN. They still served ice cream, but alcoholic drinks sold much better. We even played gigs at the Rialto, though we always got into trouble with the neighbors because of the noise.

We also often met at a rather old-fashioned pub called Ochsen in a small village called Hettenleidelheim, the home village of Rudi and the Mayer brothers. One of the biggest problems was getting from the villages to Grünstadt, and from there to larger towns, without a driver’s license or a car. Until I got my license, I used a Mofa (maximum speed 25 km/h) and had to rely on the generosity of older friends over eighteen if I wanted to get to the cool spots in bigger cities. At that time in Germany, you came of age at 21, but on January 1, 1975, that changed to eighteen. So, I was eighteen for two months before I actually came of age.

Once I could drive, we often met up in Kaiserslautern at a club called Waschbrett, which was located in the cellar of the brewery pub Benders Hauswirtschaft. Unfortunately, it closed down in the late ’80s.

We also often drove to Heidelberg on the weekends. There was a very nice live music scene in a jazz cellar called Haus Buhl or at the Cave 54. In Mannheim, we often went to the alte Feuerwache, where, in 1980, we had one of our best gigs.

What led to the decision to shorten your band name from “Punished SUN” to simply “SUN” in 1974? Did the name change reflect any shifts in your musical style or vision? What were you originally called?

The name change in 1973 was initiated by a radio presenter. Punished SUN had won a band competition, and the radio station reported on it. Apparently, the radio presenter didn’t know English well, so he pronounced “punished” the way Germans would spell the letters “punɪshed” (here I’m trying to write it in phonetic transcription), pronouncing each letter individually.

Changing the name didn’t affect the style of the music. It was just easier for those in the audience who weren’t as familiar with English—and the SUN had been punished long enough.

When did SUN officially come into being? Could you elaborate on how the band formed and how you all first connected?

SUN was formed in 1973. The musicians met in school, or they just knew each other from living in the same small villages around and in Grünstadt and hanging out in the above-mentioned spots. If you played an instrument in a rock band, we knew each other.

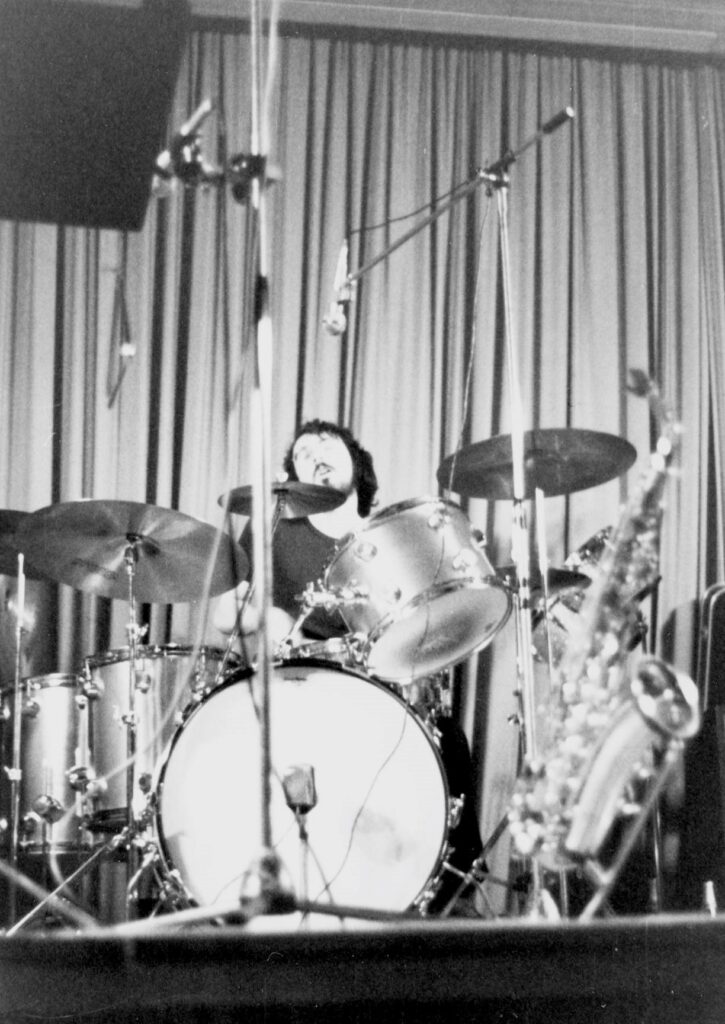

All six musicians of the 1977 SUN lineup were close friends, and the seventh friend, technician Roland “Hajo” Heiberger, was just as integrated as all the others. We rehearsed every Friday evening and Saturday morning in Reinhard “Steffen” Stephan’s old barn. After Friday rehearsals, we’d go to the Ochsen or other pubs, such as the local sports club inn, and have a few beers. These frequent rehearsals were very productive and intensive, allowing us to achieve a very high level of quality in our playing. Fast licks and complex melodies could be played with astonishing precision.

What was your setlist like in the early days? Did you perform frequently, and which bands did you often share the stage with?

SUN only played their own songs. The setlist consisted of the songs that can be found on the records, plus some others of a similar style. Back then, the songs were usually very long and consisted of many parts that loosely fit together.

In our best times, we had about 30 gigs a year. I was studying in Darmstadt and had particularly good connections to a student club called Schlosskeller, where we performed at least once a semester. We often played with a band of friends called German and American Blend from K-Town, but most of the time we performed on our own.

In 1974, you contributed two lengthy tracks to the double LP ‘Proton 1,’ sharing space with bands like Zyma, Andorra, Penicillin, and Nexus. What do you remember about that project and how it influenced your band’s trajectory?

I wasn’t involved in the 1974 recordings, but I remember some stories that were told to me.

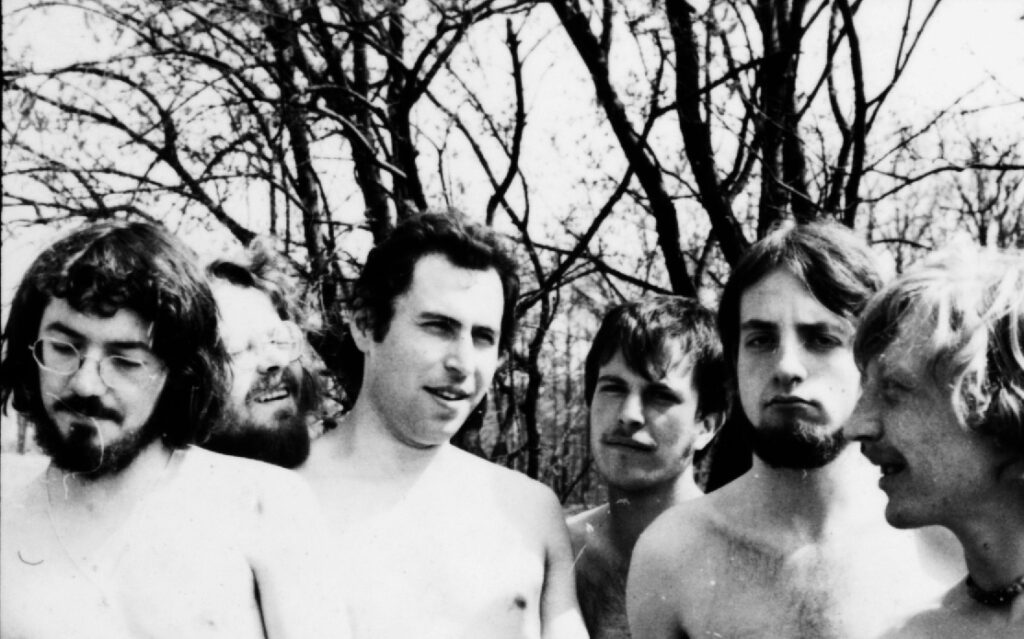

There was a legendary time when the band rented an old farmhouse in Kerzweilerhof, in the middle of nowhere, and lived there together. I was never there, but they were always playing music, partying, and having a lot of fun—some say they even danced naked around a campfire. However, it also ended with a few disagreements.

One story I heard, for example, was that Bruno, who mostly played bass at that time, wanted to learn the saxophone. So, Bruno Mäder pretended to his parents that he was going to university to study, but instead, he went into the forest and entertained the forest dwellers with his practicing.

The guitarist, Harry Müller, owned a Fender Strat. Since it’s said that a Strat never has perfect fret intonation (I couldn’t find a good English translation of Bundreinheit), he almost went crazy trying to find the right tuning. They even went out during the recording session to buy new strings, but it didn’t bring any improvement.

The studio owner, Kersten, must have been quite a charismatic person, and in the end, they delivered a good-sounding record. In my opinion, the songs are somewhat inspired by Irish folk songs and harmonically similar voicings. The two brothers, Peter and Dieter Mayer, have excellent singing voices. Harry and singer Dieter Mayer both studied music and performed very successfully as the duo Flute, Strings and Voice from the late eighties until recently.

Personally, I think Zyma had the best sound. Dorle Färber’s voice is truly fascinating.

Can you tell us about the gear you used—your instruments, amplifiers, and other equipment in the band?

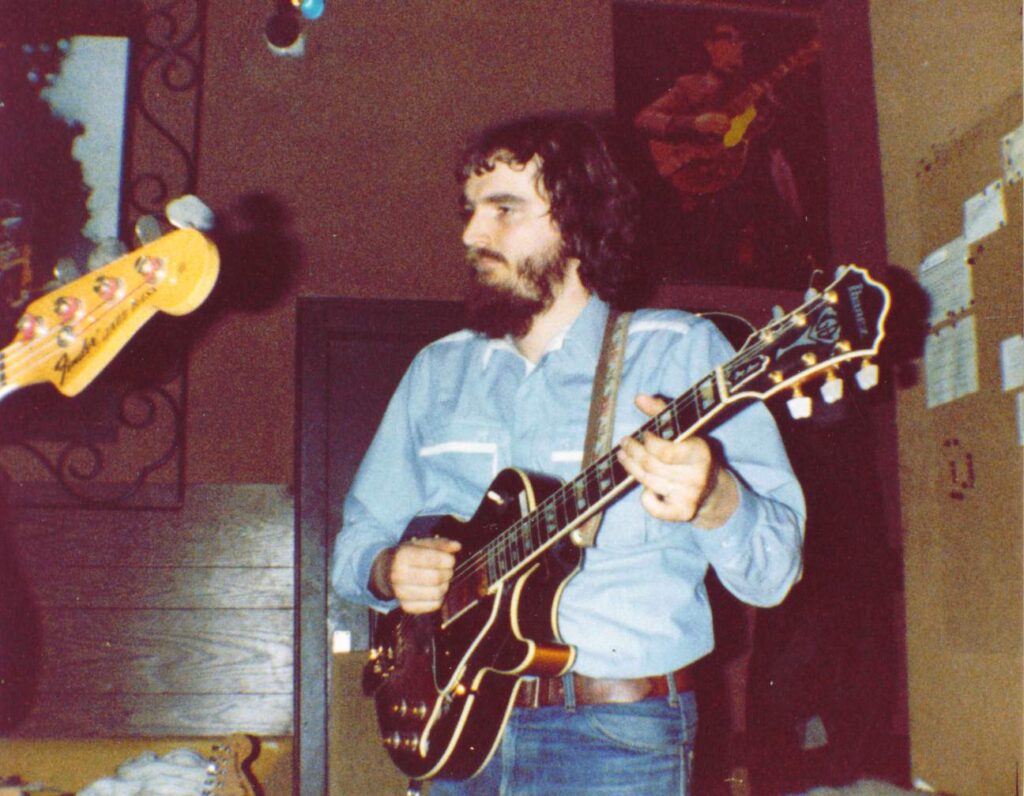

In my pre-SUN days, I had the aforementioned Höfner with a plastic skin. After the Echolette BS40, I played a massive Winston tube amp stack with two 4-speaker cabinets. It only sounded good if you used the “British setting,” meaning all the controls at the full 12 o’clock position. But nobody could stand that volume. So, I used a cheap Schaller distortion unit to create distorted sounds that you couldn’t really call “sound”; it was just awful croaking. Later, I played a Dynacord amp for a brief time before switching to a Fender Showmaster. I also played a Höfner AZ10 full-body jazz guitar and successfully avoided early feedback by turning the guitar’s bass and treble controls to zero. I replaced the plastic-head Höfner with a Gibson L6S and also played a Fender Jazzmaster. That was when I joined SUN. My favorite effect was the “Small Stone” phaser from Electro-Harmonix. Sometimes, I used a Wah pedal. Eventually, I invested in a German tube amp called “Vintage” from PCL. It was a kind of Boogie simulation. However, Harry’s Boogie Mark I sounded remarkably better. You can hear my Vintage and Harry’s Boogie on the 1980 recording.

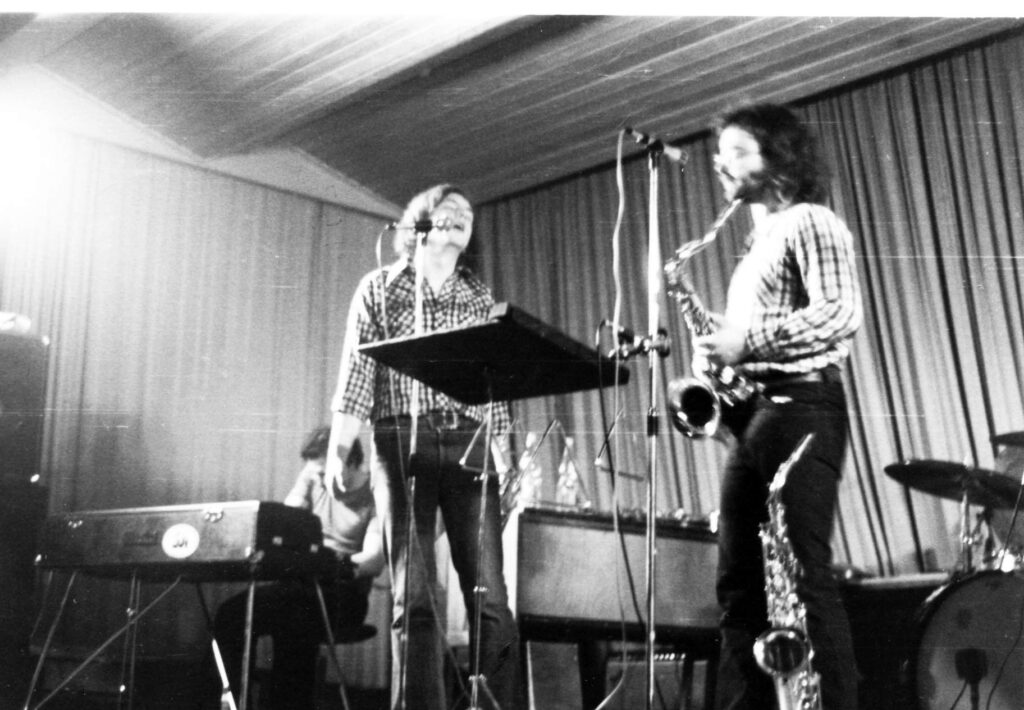

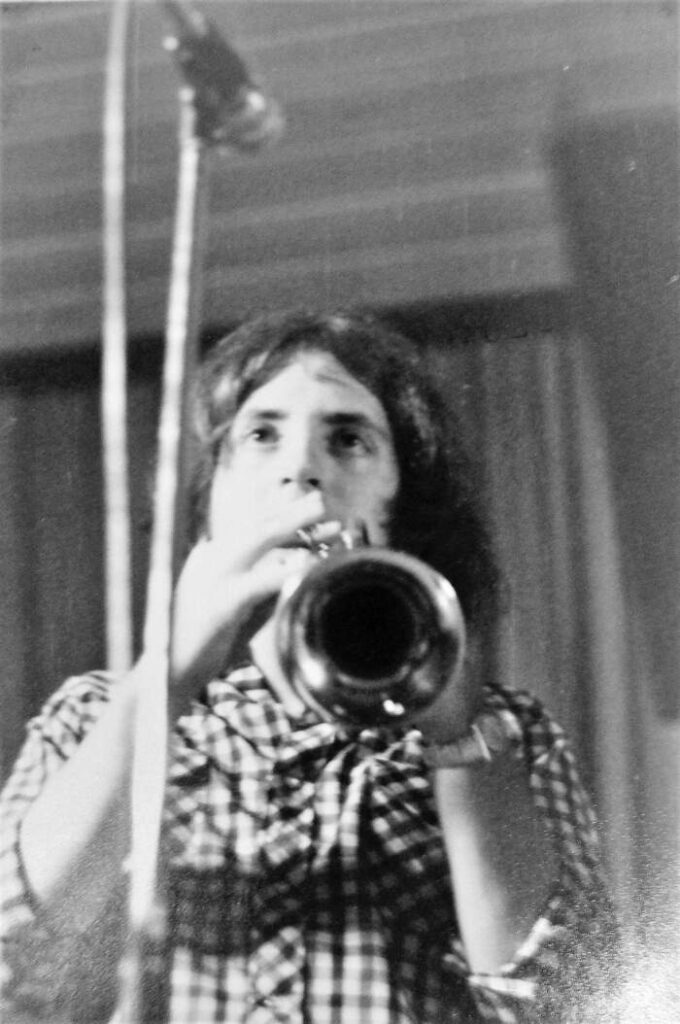

The bass player, Thomas Heldmann, played a Fender Jazz bass, sometimes a Rickenbacker, and was very fond of a Travis Bean. The drummer, Rudi Herrmann, never played anything other than his Hayman drum set. The heaviest piece of equipment was a Hammond M3 organ, divided horizontally into two parts so we could carry it around. Attached to the Hammond was a Leslie, and we also lugged a Fender Rhodes piano with us, as the trumpet player, Hans-Joachim “Seele” Krämer, was also incredibly skilled at playing keyboards. Because of all the lugging, we were often completely worn out before playing a single note.

The PA initially consisted of two column-type speakers from Shure and two six-channel power mixers from Shure, but they didn’t provide enough power. We then switched to the legendary Stramp mixers and power amps.

To boost power in the low frequencies (since subwoofers weren’t really known back then), we built our own huge “Eliminator” speakers, a hobby that Hajo was deeply absorbed in. We used two Vitavox horns for the mid and high frequencies, but they were always prone to feedback, and I’m afraid they damaged my hearing in those ranges. I have a strong dip in my hearing frequency response from 2000 to 6000 Hz.

Since the Eliminator speakers were too big to carry around all the time, we switched to two homemade smaller bass speakers with 15” Electrovoice speakers. The Fender Rhodes was often hooked up to an MXR distortion box and also to a phaser.

The saxophone player Bruno used very special equipment. He had a Lyricon, an air-controlled synthesizer that could be played like a saxophone. In 1981, I purchased a Variophon, also a synthesizer specialized in horn sounds, but played with a monophonic keyboard and blow control. We used it mainly to simulate trombone sounds. A little later, I started learning to play a real trombone and still play it today in bands. Both the Lyricon and Variophon quite soon vanished from the market.

Were you connected to any booking agencies?

In the early days of Punished SUN, there was a guy, Klaus Lindemann, who acted as a kind of manager. He must have been an extraordinary person. The relationship ended in the early ’70s. A story about him can be found in the CD booklet that comes with the CD released in 2007.

Later, we did all the booking ourselves. Not only was the rehearsal room in an old barn on the keyboardist Reinhard “Steffen” Stephan’s farmhouse in a village called Tiefenthal, but he also organized everything, including the aforementioned festivals. He organized concerts and festivals until 2023, in particular the Rock im Hof festival in the village where he lived, Nackterhof.

What’s the backstory of your self-released 1980 album? Where did you record it, what equipment was used, and who produced it? How much time did you spend in the studio?

After the recording of ‘Proton’ in 1974, Dieter left SUN. He began studying flute in Darmstadt and became heavily involved in the Mannheim music scene. A little later, Peter left SUN and signed on as a sailor, sailing the (seven?) seas. Now there was no more singer. What was to be done? Bruno took over this task, and because he preferred to play saxophone, Thomas Heldmann, the bass player with whom I played in Omicron, joined SUN in 1975, and with him came Hans-Joachim, the trumpeter. When Harry left SUN in 1977 to study guitar and was told that playing electric guitars with a pick would destroy the classical style, I joined as his successor. Around 1979, Harry realized that playing electric guitars was fun and didn’t hurt the classical style, so he came back to SUN.

For the recording of the 1980 album, we spent one week in the studio, Tonstudio Krings in Usingen, about 30 minutes north of Frankfurt. Peter Krings didn’t want to be mentioned on the disc cover; however, his recording engineer, Detlev Klaus, is acknowledged. During the recording session, we all stayed in the shared flat where our singer and bass player lived together in Frankfurt.

A nice background story is that on the day we set the recording date (end of March, Easter 1980), daylight saving time was introduced for the first time in Germany. The recording was set for 9 o’clock, but none of the band realized the time difference. We’d had a few drinks the night before because we’d been having a lot of fun in the flat share, so we didn’t arrive at the studio until well after 10 o’clock. The studio team, however, was very aware of the time shift and waited over an hour for us; they weren’t exactly amused. But once we started, the mood improved, and we had a lot of fun despite the stress, since we’d booked the studio for exactly one week at a flat rate of 5000 DM for recording and mix-down. By the end, we were running out of time. If anyone had to repeat a take, the others reminded them that every minute of delay cost about one DM!

We produced the record ourselves. Distribution was handled by a friend, Michael Stühr, who ran MS Edition in Darmstadt. He also provided his label code, LC.

Can you walk us through your memories of the recording sessions? What inspired the songs you recorded?

The songs chosen for the record were simply our favorites from our repertoire. As you can imagine, we struggled with the limitations of the equipment back then. The 16-track Studer tape had an issue where, if you stopped recording for overdubs in the middle of a song (punch-out), a popping noise would appear on all tracks. So, if there was a mistake, you always had to let the tape run until the end of the song.

Another interesting piece of equipment was the reverb unit, a “reverb” disc, which was built by the studio boss himself. It was a large rectangular metal plate with a small speaker attached to it. The plate was also equipped with 6 or 8 pickups, similar to those used in normal record players. The delay and oscillation of the metal plate between the speaker and the pickups created the reverberation.

We were always on the lookout for new, previously unheard sounds, so Bruno played a Lyricon on some tracks. It was the first synthesizer with a wind controller and could play over four octaves, although setting up the sounds was very challenging.

Since we were all students, we didn’t have much money, and I still regret today that we didn’t buy the 1-inch 16-track tape. The studio owner wanted to sell it to us for 200 DM, but nobody could afford it. That’s a shame, especially because we were inexperienced and avoided using compressors out of a self-imposed dogma. As a result, the sound of the record is a bit flat and lacks volume. At least the recordings were normalized and compressed a bit at the record-cutting studio.

Could you offer some insight into the tracks on the album?

Our favorite song was ‘Ohne Titte.’ At that time, we thought playing with the German phrase “Ohne Titel,” meaning “untitled,” was funny. It was inspired by ‘Meeting of the Spirits’ from the Mahavishnu Orchestra’s record ‘Inner Mounting Flame.’ The Spanish sound and corresponding musical scales (Phrygian) always inspire guitarists, which led to ‘Neulich in Spanien.’ On this track, Harry plays an acoustic guitar without a pick, using only his fingernails. The title ‘Neulich in Spanien’ is a nod to the famous comic artist Don Martin, as the German titles of his ultra-funny comics had similar phrasing.

‘The Jester’ is a piece that consists of vastly different parts, ranging from a sort of ¾ Irish folk tune to sections with odd time signatures and operatic sounds, ending in chaos and then a bluesy finale. My favorite part is the 7/8 section after the intro, which speeds up to warp speed in the reprise. We loved performing this live because it had a recitative part, like in an opera, and Bruno especially created a playful mood with it. The lyrics were performed in different voices, making it more than music—it was a performance. Another live song not on the record, ‘Fever in my Brain,’ had a similar energy and always made the audience smile.

‘On Holiday’ was clearly inspired by Frank Zappa’s genius sound. ‘Women’s Lib Blues’ starts with oriental sounds, like a Harem scene, and ends in Rock ‘n’ Roll. At that time, most of our lyrics were written by Klaus Lösch, who studied English literature and used unusual phrasing that was sometimes hard for us to understand. He was often sarcastic and, by today’s standards, perhaps a bit sexist; this song parodies the Women’s Liberation movement that became prominent in the late seventies. Unfortunately, he passed away too soon.

‘Seeing Similaun’ has its own story. Similaun is a big mountain in the Austrian Alps near Sölden in Ötztal. Since we were all good friends in the band and spent a lot of free time together, we decided to have a winter vacation together. So, we rented a hut in the Ötztal Valley. Not everyone in the band was interested in skiing, and the weather wasn’t great, so we had a lot of time to make music with two guitars, the sax, and the trumpet player. After countless beers, we came up with this song. It’s dedicated to this mountain. Some evenings we went to a pub and, once, to a disco where our technician Hajo met a girl from Munich. Not long after, he moved to Munich and left the band.

The track titles on your album, such as ‘Ohne Titte’ and ‘Und ewig heulen die Gitarren,’ are quite unique. Can you shed light on the stories or inspirations behind these intriguing titles?

As I mentioned, Ohne Titte is a song inspired by John McLaughlin, and I had the first ideas for it when I was sixteen. The title ‘Und ewig heulen die Gitarren’ is another attempt to add humor to the title. There is no distorted “wailing” (heulende) guitar in the piece at all. I played the jazzy theme in a low voice on a Korg MS20 synthesizer, in a duet with the tenor saxophone.

Your album was privately released—how many copies were pressed?

We had 1,000 copies pressed on 180g vinyl. The cover was printed by a printer friend of ours, who was actually the former drummer of omicron. However, he had no experience making record covers, so there was no fold to accommodate the thickness of the record, and we had to fold and glue the albums by hand. We used an unsuitable adhesive, and some albums came apart very quickly. Every fingerprint showed up on the black surface of the cover. So, we complained to the printer, and he coated the cover with varnish. Since we didn’t want to pay for this, our friendship with the drummer-printer was more or less over.

We used the label code (LC code) of a publisher friend from the alternative scene in Darmstadt. His name was Michael Stühr, and today he makes his living by offering prepress software. Incidentally, I also used to work in the printing technology industry.

How did you go about distributing the records? Were they sold in local stores, at gigs, or sent to radio stations and labels?

Yes, we distributed the records in local record stores, especially in Darmstadt. In Frankfurt, there was a great distribution store where we placed at least 500 copies. We received a bit of money from that. Additionally, we sold the record at gigs and sent copies to radio stations. However, as far as I know, they were never played on the radio except for Seeing Similaun, which was aired in a documentary about local bands.

What happened with the band after the album was released?

After the album’s release, we had some very nice gigs. Later, in 1982, we started to get increasingly experimental with sounds, unusual melodies, and irregular time signatures like 9/4 rhythms. We also began incorporating more German lyrics. Reinhard “Steffen” Stephan left the band because he didn’t like this direction. For us as musicians, it was challenging, but the audience didn’t appreciate it.

Additionally, sax-player and singer Bruno Mäder got a job at SWR radio and didn’t have time for rehearsals anymore. He got married, and not long after, he suffered from acute hearing loss and tinnitus, so he quit music completely. To replace him, we brought in a female singer who performed in the style of Urszula Dudziak, a unique scat jazz performer. Unfortunately, this direction also didn’t resonate with the audience, and this period of SUN lasted only about half a year. The SUN era was over.

We then formed a funk rock band called 8 Atü, with a horn section where I played trombone. We mostly played covers, with only two or three old SUN songs. ‘Ohne Titte’ remained.

When did you all eventually decide to stop playing together?

The end of this period of SUN was in 1982. In 2005, we reunited for the “Return of the SUN.”

Garden of Delights issued some bonus tracks. What can you tell us about these previously unheard pieces?

There are actually four bonus tracks. Before we went to the recording studio, we did some recordings ourselves in an old barn in Tiefenthal, where we built a wall with a window to convert it into a kind of recording space. Two of the bonus tracks, ‘Slaves of Heaven’ and ‘Communication,’ were recorded by Hajo. At that time, Harry was not a member of SUN, but Hans-Joachim played trumpet.

The other two bonus tracks, ‘Morning Dream’ and ‘Black Sheep of the Family,’ date back to the 1974 era but were recorded in 1994 in our rehearsal cellar. This was in the cellar of the house where Rudi, the drummer, lived. From 1993 to 1995, band members Thomas Heldmann, Rudi Herrmann, and Gunter Hübner, who continued to make music together even after SUN split up, joined forces with founding member Peter Mayer in another brief, very creative phase. The band, which at the time called itself “No Sports” or “No Shorts” and mainly played cover songs, also condensed these old, complex SUN songs down to the essentials. In 1994, these two tracks were recorded on an eight-track tape. The recordings were digitized in 2007 from the eight-track tape and enriched with overdubs by singer Dieter Mayer, Peter’s brother. What’s fascinating is the harmony and tension in the Mayer brothers’ remote duet, sung 13 years apart. Sadly, Peter passed away recently, in 2024.

What’s the wildest gig you ever performed?

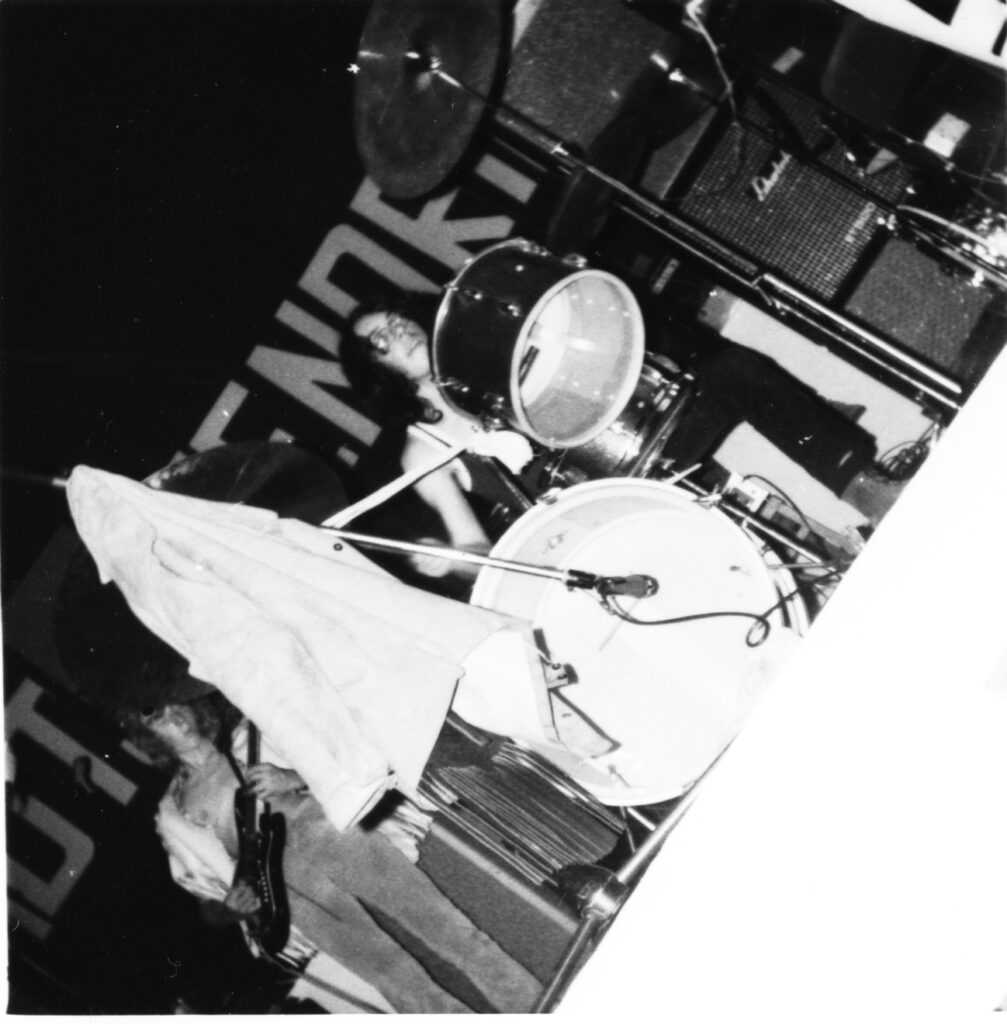

It was around 1980 at a festival in Hauenstein, where about 2,000 enthusiastic people were in the audience. The gig at the “Alte Feuerwache” in Mannheim was also sensational.

Did any of the members join other bands during that time or later in the ’80s?

Yes, as mentioned above, there has always been a certain fluctuation of band members. I’ve attached a “family tree.” During the “Return of the SUN” period, bass player Thomas left the band, and Hajo Zitzkowski joined. He’s a website specialist, runs the current website www.sunmusic.de, and compiled this complex tree chart.

What has your life been like since those days?

I always think back to the old days very fondly. But I’m also glad that I was successful in my profession as an engineer and never became a professional musician. If you’re not a top musician, you always have to struggle for money and end up teaching children how to play an instrument. I have, however, always continued to make music, and now, as a pensioner, I’ve even intensified my music-making—I’m currently in four (!) bands.

Have you stayed in touch with the band members over the years?

Yes, especially with Thomas, Rudi, and Harry. A bit less with Reinhard, Dieter, and Hans-Joachim. I’ve seldom met Bruno and Hajo Heiberger. With the new singer (since 2013), Bärbel Sonnenfroh, I now play the old SUN songs in a new formation called Amber Moon.

What are some of your favorite memories from the days of SUN and the ’60s/’70s in general?

Uhh, there are so many great memories. But the best part has always been feeling the applause and appreciation of the audience.

What’s keeping you busy these days?

Now that I’m retired, of course, my family—my wife and my two grown-up children—are the most important thing in my life. I’ll soon become a grandfather. But I also still pursue my favorite hobby, making music.

Thank you for sharing your stories. Any final thoughts you’d like to leave us with?

They say making music prevents the elderly from getting Alzheimer’s, so that can’t happen to me. My dream, hopefully a long way off, is to fall over on stage during a wild and furious guitar solo, ending my life that way.

Klemen Breznikar

SUN Official Website

Garden of Delights Official Website