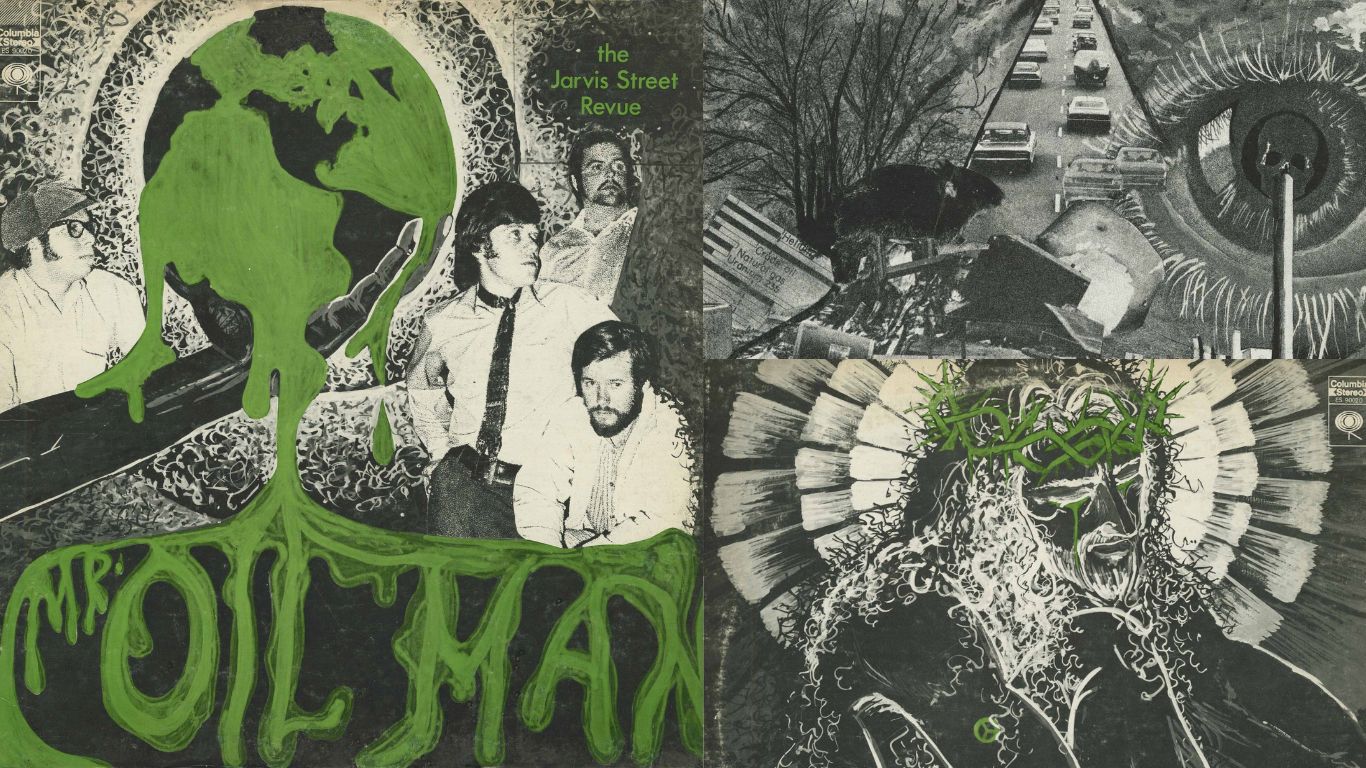

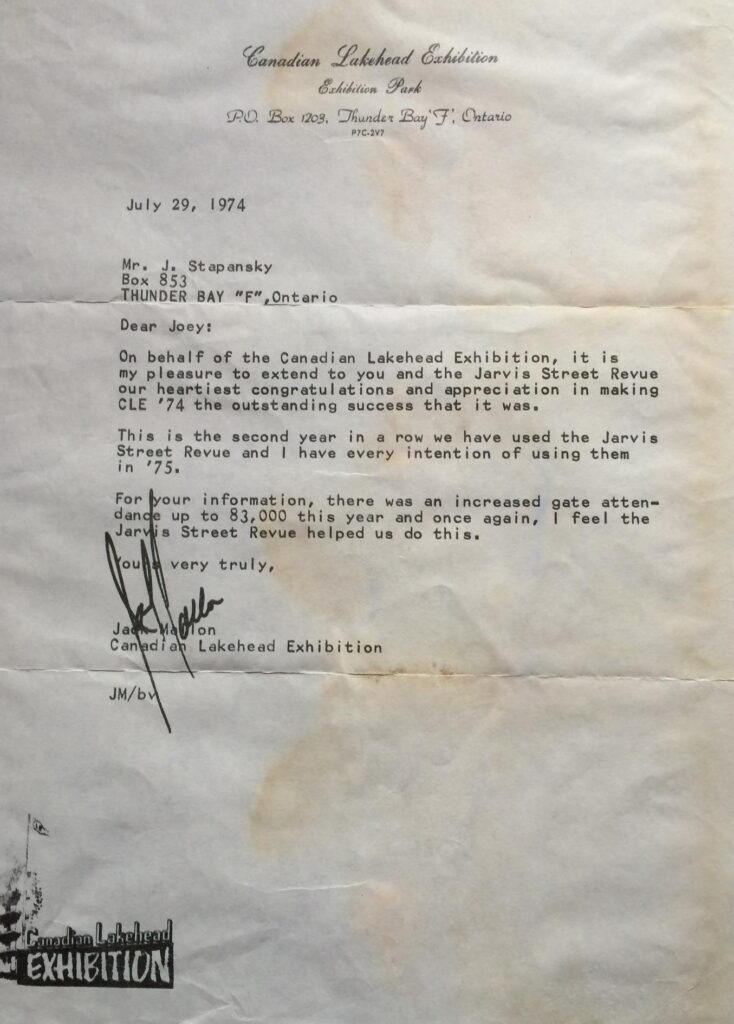

The Jarvis Street Revue | Interview | “Mr. Oil Man”

The Jarvis Street Revue, with their anthem ‘Mr. Oilman,’ delivered a scorching, eco-punk rebuke, slamming the greed of Big Oil long before anyone else was talking about it.

What we have here is a monster of heavy psych, a record that stands as a prime example of the genre. Their sound was as chaotic and beautiful as the world they raged against—a concoction of blues, rock, and pure, unbridled psych that couldn’t be pinned down. While most bands were chasing the Top 40, the Jarvis Street Revue made their own rules—and broke them. Sure, they had their share of bad luck and worse management, but their refusal to bow to the industry’s demands made them unique in the truest sense.

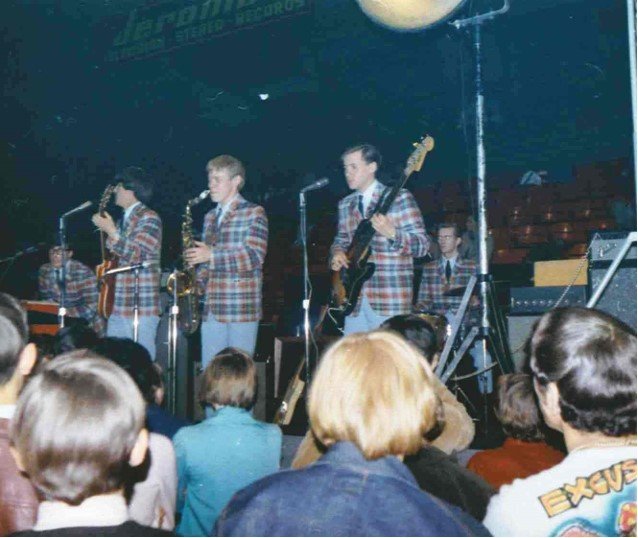

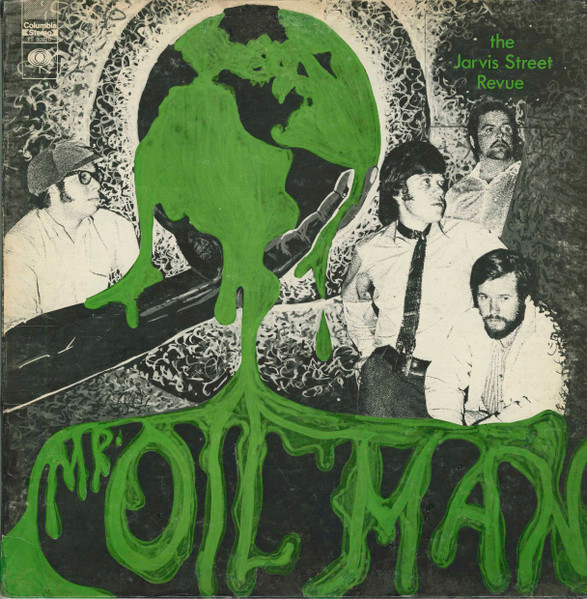

The Jarvis Street Revue emerged in Thunder Bay, Ontario, during the late 1960s, formed by Tom Cruickshank, Wayne Faulconer, Tommy Horricks, and George Stevenson. Horricks and Stevenson had previously played in the Toronto-based band The Plague (among others). In 1970, the band released their lone album, ‘Mr. Oil Man,’ recorded at DMG Sound Studios in Thunder Bay. The album’s lead single gained some local attention, and its gatefold cover features a striking image. The album’s lyrics address environmental concerns, particularly the exploitation of oil reserves and the depletion of natural resources.

The Jarvis Street Revue’s Eco-Rock Revolution: Tommy Horricks’ Take

I grew up in a city that no longer exists, called Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada, now known as Thunder Bay. I was born in October 1943 at the General Hospital, which also no longer exists. I went to a public school called St. James and Lakeview High School, both of which no longer exist. My parents had no musical abilities whatsoever, but they loved to dance, and I learned many songs listening to Al Jolson, the great Caruso, Eddie Cantor, and so many others on our wind-up gramophone player. Today, some 70 years later, I still remember the lyrics and melodies to many of those songs. I made my first public appearance at Knox United Church when I was six years old and sang a Gene Autry song called ‘Have I Told You Lately That I Love You.’ Amidst the applause, I caught the enthusiasm and clapped as well. It took me years to get over the embarrassment of realizing that you are not supposed to clap for yourself. As a result, I suffered stage fright for probably forty years. My father, who worked in the Abitibi Paper Mill, advised me not to follow in his footsteps. He said that if I joined a company, I might look back on my life when I got older and feel that I had wasted it.

My parents were the only ones on the block who weren’t saying, “Learn to use a shovel.” I was sent to the convent to study piano lessons when I was six years old. I remember the nun hitting my hand with a ruler when I made a mistake. As the tears welled up in my eyes, I vowed I would never give anyone an excuse to hit me. Although it physically hurt, I felt indignation at some stranger hitting me. This drove me to apply myself to my lessons and truly learn them. That was a game changer for me, as I began to receive praise and earned First-Class Honours from adjudicators in the Royal Conservatory of Music. I became a child prodigy and enjoyed all the praise. It became too much as time went on, and my mother began showing me off to all her friends. To make matters worse, at the age of 12, I was made to study the history of composers. I was too young to appreciate history and only wanted to learn more music, so I quit the formal lessons. Ironically, later on, I found myself fascinated by the lives of composers from the past while reading the liner notes of albums. By then, of course, I had become old enough to understand history.

At my Grade 8 graduation, I saw Bob Sills playing a tenor saxophone and thought, “That’s what I want to do.” Upon entering high school, my music teacher, Savile Shutterworth, told me that if I wanted to become a great saxophone player, I would have to play the clarinet first to build up my embouchure. This meant I had to sit in the front row with all the girls who couldn’t play without squeaking—for two years.Because of my early start in music, I was miles ahead of everyone, and my music teacher loved to have me in his class. He even let me skip out of English class on Friday afternoon and spend the whole afternoon playing music. Earlier, I had decided to devote my life to music, and I lived, breathed, and did nothing else.

My Dad brought me a King Silversonic Tenor saxophone, one of the finest instruments of the day. At 15, when Boots Randolph came out with ‘Yacketty Sax,’ I spent three days in my room, wore out the record, and when I came out, I was a saxophone player. I was always introverted and shy, and people find that hard to believe, and my first ambition was to become a research scientist and cure disease. This was because my mother got rheumatoid arthritis when I was 10 and was in the hospital for a year at a time. Later on, in a conversation with Bobby Curtola, I asked him what he was going to be when he grew up, and he said, “a singer.” I thought, what an awesome idea to get paid for doing something that you loved. Around that time, a friend named Stan Forneri, who was a very forceful and pushy person, came to visit me as I was puttering in my lab in the basement and literally forced me to get my saxophone and go to Knox Church and play for the Tyros, who were a church group similar to the Boy Scouts organization. I remember having this beautiful vibrato that was issuing out because I was shaking so much. Stan later became the drummer of the first band I was ever in, called The Nobles. The first time we played at the Hurkett Recreational Centre, I got $1.26, and I remember how thrilling it was to get paid doing something I loved.

One day, a fellow by the name of Ronnie Gee came to our rehearsal and said Stan and I were good enough to join the union, and without even knowing what was happening, we were drafted into Ronnie & The Comets, who were a fairly professional band and performed at the Lakehead Exhibition Auditorium every Friday. My job consisted of sitting at the side of the stage with a couple of girls and going up and playing the last two songs of the set. It would be a Johnny and the Hurricanes song called ‘Crossfire’ or something to that effect. The crowd would put me on their shoulders and parade around. Later, I would be driven to Black Mike’s in Current River, a subsection of Port Arthur, and get several bottles of wine to bring back and drink with the band in the dressing room.

At this same time, I got the only legitimate job I have ever had. I worked for the Bank of Montreal and, in the course of that year, did every job in the bank, including balancing the books. The charter said a good employee was to come early, stay late, be willing to travel, and not get married. I was making $68 every two weeks, and one day, the assistant manager said that I had not drawn out my salary. I innocently told him that I didn’t need it. He hated me after that and always gave me unpleasant things to do. I didn’t mean to be anything but truthful when I said I didn’t need it. I was making more money in six nights with the Comets than my Father made in a month after 35 years in the paper mill. Needless to say, when the bank manager asked me to stay, I joyfully refused. I had discovered sex, drugs, and Rock’n Roll. The Comets went on to record in Minneapolis at Soma Studios, where Prince later recorded, and I recorded a saxophone song called ‘Milestone,’ which became a number-one song on the radio in my hometown.

There I was, 16 years old with a hit on the radio, driving around in my 1957 cream-and-red Ford Fairlane Convertible. I have been happy all my life, but that time set the bar pretty high. As time went on, a new band became the rage, and the Comets disbanded because the new manager wanted a lifetime exclusive contract. I was approached by “Donnie B and the Bonnvilles,” a band managed by Al Smith, who was involved in the YMCA. They had just finished being the warm-up band for the Beach Boys at the Fort William Gardens and were rapidly becoming the most popular and successful band in the area. They wanted a sax player, and that was me.

What made them extraordinary was Lynn McEachern, the drummer, who had the ability to sing wonderfully while keeping the audience engaged with his narrative. Further to this was the fact that the manager, Al Smith, was a mature and personable adult in charge. The next thing I remember was being the backup band for Jay & The Americans, six Jewish fellows from New York who came with just one guitar player who taught us how to play all the songs. Donny Brown was almost killed when he called our piano player “Jewy,” until we explained it wasn’t a racial slur—it was just a term of affection he used. Being from Thunder Bay, we had no idea of racial prejudice. We were all like brothers at that point in time.

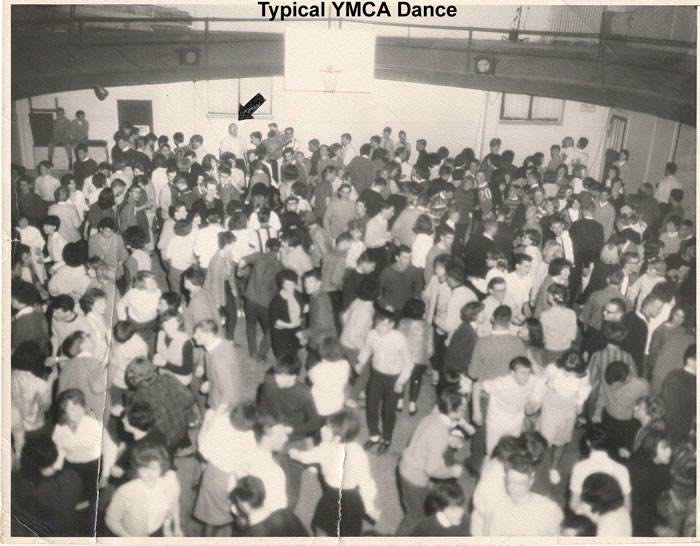

Being the backup band for a major act accelerated our musicianship and professionalism. We had a contract playing dances in the Fort William Gardens that had 3,000 to 5,000 kids every Friday. We had a radio show and were performing on the Dick Wilson television show once a week. Eventually, the city got greedy and decided to get another band, and that was the end of the dances. People came to see the Bonnvilles, and the city dances were over in a couple of weeks.

We decided to continue and booked ourselves into the Fourth Dimension Coffee House, which legally held 300 people, and we packed in 700. It was so full that it took me 10 minutes to squeeze through the crowd to get to the back and buy a drink. I was so thirsty and hot, and the cokes were in little cups that I would down six of them, go back to the stage, and freak out to the music. People thought I was on drugs. It was the Coca-Cola.

“I wrote ‘Helpless’ in the YMCA with Neil Young”

We played Rolling Stones, Beatles, The Knickerbockers, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Dave Clark 5, and all the popular songs of the day. It was around this time that Neil Young came to Thunder Bay with his group called The Squires. Some publications have said I was in The Squires, but that’s not true. What is true is that I wrote ‘Helpless’ in the YMCA with Neil. He has repeatedly denied that it was written in Thunder Bay and claimed it was written in his hometown in southern Ontario. I always gave him the benefit of the doubt that he had forgotten, but now I’m not so sure.

We hung around together for about a year, and he conveniently forgot my name as well. Neil was playing at the Circle Inn and called his band The High Flying Birds. He named the band after a song that he taught me called ‘High Flying Bird.’ I later recorded it, and so did Neil, as well as Jefferson Airplane. Our friend Terry Erickson, aka Doc Tibbles, had a nightclub job in Sudbury and needed to get there. We asked Neil if he would drive us, and he agreed. Donny Brown and I funded the trip and went along with Neil on the fateful journey to Iron Bridge, where the hearse broke down, and then on to Blind River, to the junkyard where “Mort,” as Neil called it, met its final resting place. We gave Neil all our money, but he gave us back $3.65, and we hitchhiked back to Port Arthur with his drummer, Bob Clark.

The Bonnvilles decided to record after saving a couple of thousand dollars, and we hired Don Grashey as producer. He knew Gary Paxton, who had a studio in Hollywood. Our lead guitarist, who was a fiery red-headed showman, refused to go, saying he had a good job and a steady girlfriend. She left him shortly after he left the band, and he lost his job about a year later. The band was slightly wounded by his loss, but onward and upwards, off to Hollywood we went.

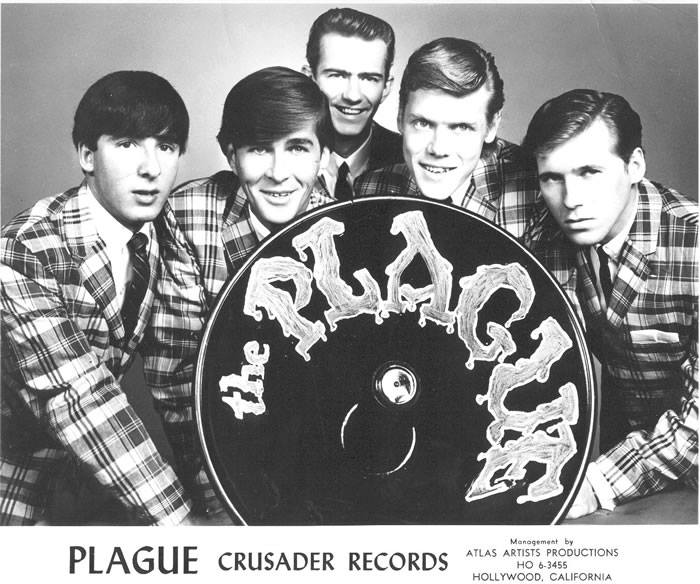

We decided to change the name of the band to something more modern, so we became The Plague. The van had all this puke and stuff on it with the slogan: “The contagious sound of The Plague.” It was evening when we reached the Strip in Hollywood, and the street was lined with hundreds of people.

I reached out of the window and gave the peace sign. There was a rumble of cheers and a wave of peace signs radiating up and down the boulevard. Someone came out of a club called Pandora’s Box, asked if we were a band, and if we wanted to play there. We quickly went in and met the band who were playing there called World War Three. They had long blonde hair down to their knees, with only their noses poking out.

We went to the stage, and of course, the place had a funny smell. We had no idea about grass or drugs at this time, so we played our rendition of Jay and the Americans’ ‘Only in America.’ This song caused a complete silence after it was over, so I quickly got the band to play ‘Bo Diddley’ with an arrangement I had put together from watching Ronnie Hawkins and The Band at Le Coq d’Or, Ronnie’s nightclub in Toronto. This put everyone into a frenzy, and I remember, as I was singing, looking out of the window and seeing the marquee of Whiskey a Go Go, with the words now appearing: “The Doors.”

I’m sure The Doors must have been in Pandora’s Box because when they released their album with ‘Bo Diddley’ on it, the arrangement was almost identical to the one I had put together using ‘Who Do You Love’ as a medley with ‘Bo Diddley.’ The next day was another adventure to find Gary Paxton, who had disappeared. I found this flowered-shirted fat hippie out on a golf course with a single golf club. He had a driver, and I’m not sure what he was on, but I begged him to come back because we had come thousands of miles for him to record us. He agreed, and the next thing I remember was he had a bus with the recording gear, and his garage was his studio. We recorded several songs, but when we recorded ‘The Face of Time,’ a song I had written with my DJ friend Ray Dee, Gary went ballistic. He told us that he had just finished recording two million-selling records, and we were going to be next. He said, “Go back to Canada and wait for this to come down on you. You are going to be huge stars.”

At my grade eight graduation, I heard a fellow by the name of Bob Sills playing a tenor saxophone and said to myself, “That’s the instrument I want to play.” Earlier, as I was trying to decide what to do with my life, I had become interested in yoga and hypnotism and was considering becoming a preacher, but I couldn’t find a religion I could identify with. So, I considered music and thought it would be honorable to devote my life to it. I lived and breathed it, eventually playing seventeen instruments.

Upon entering high school, we had instrumental music classes, and I asked Saville Shuttleworth, our teacher, if I could play the saxophone. He told me that if I wished to be a great player, I would first have to learn the clarinet to develop the lip embouchure, progressing from smaller to larger instruments. So, I was sentenced to playing clarinet with all the large girls who squeaked and squawked for two years.

As I was developing an embouchure, I learned to play many other instruments, and eventually, I was up to fourteen. I had made a vow to dedicate my life to music, so I lived, slept, and breathed it. I remember one time playing the hand cymbals for an adjudication in an orchestra performing a symphony, and the adjudicator gave a special mention to me as the conscientious cymbal player. He could see the efforts I made as I counted the 132-bar rests before the crash. Of course, I couldn’t maintain fourteen instruments, so I have settled on saxophone, flute, clarinet, guitar, and harmonica.

Before I had decided to become a musician, my intention was to be a research scientist and find the cure for diseases. My mother suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, which she developed when I was ten years old, and she died of it some twenty-five years later after spending a year in the hospital at a time. I have always had a strong interest and thirst for knowledge in biology and medicine.

One day, when I was about twelve years old, my friend Stan Forneri came to visit me while I was messing around in my laboratory in the basement my father had built for me. Stan was a rather aggressive and pushy guy, and he insisted that I get my alto saxophone and go to Knox Church to play for the Tyros, a church organization similar to the Boy Scouts. I was extremely shy and had no confidence, but he was determined, and I reluctantly went along with him.

I played a song for them called ‘Velvet Waters’ by the Megatrons. I was shaking so badly that I had this beautiful vibrato, and of course, this was a turning point in my life. The ability to play music for people and give them pleasure is addicting, and I was hooked. Stan was a drummer, and we joined a group of fellows and called ourselves “The Nobles.” The group consisted of Arby Young on rhythm guitar, R. Thomas Kelley on lead vocals, Stan Forneri on drums, and Harold Mills on lead guitar.

Our first performance was at the Hurkett Community Centre, and I remember looking at the three dollars and twenty-six cents in my hand, amazed and grateful for being paid for what I loved to do.

We started rehearsing, and after several gigs, a fellow by the name of Ronnie Gee (Goyda) came to see our band. He promptly told us that Stan and I were good enough to join the union, but that the others should keep practicing. Without even realizing what was happening, we were drafted into his band called “Ronnie & The Comets,” who played every Friday at the exhibition auditorium. It was a fairly professional band, and I was paid very well to sit at the side of the stage until the last few songs of the set. Then, I would get on the stage and blast out a rendition of ‘Crossfire’ by Johnny and the Hurricanes or an instrumental song I had written called ‘Milestone,’ which we later recorded at Soma Studios in Minneapolis, the same studio used by Prince.

Being an only child, my dad bought me a King Silver Sonic silver bell tenor saxophone, and he also gave me a ‘57 Ford Fairlane cream and red convertible. My song was number one on the hit parade for six weeks. To top that off, I was making more money in six nights than my dad made in the paper mill after 35 years of working. Pretty good for a sixteen-year-old kid!

Around that time, I got my only legitimate job I’ve ever had in my life. I went to work at the Bank of Montreal, and my salary was $68 every two weeks. The assistant accountant said that I hadn’t taken my salary from my account. I innocently replied that I didn’t need it. He hated me after that and always gave me a hard time. After one year, I was invited to stay, but I had discovered sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll.

The Comets’ dances were very successful but quite rough. There were constant fights going on, and they were brutal, but about this time, marijuana came on the scene, and the same people were in the corner saying, “Peace, brother.”

R. Thomas Kelly from the Nobles went on to be a folk singer and then later became cohost of Singalong Jubilee with Ann Murray. Although it looked like he had a chance for greatness and he was an awesome vocalist, his career never flourished. Before he passed away in 2006, I produced an album for him called ‘The Legacy.’ Unfortunately, it seems no one has interest in an artist who is no longer with us.

Continuing on with Ronnie and the Comets, after the first set, the audience would put me on their shoulders and parade me around. I would then leave with a couple of girls and a driver and drive to “Black Mike’s” in Current River, a district in Port Arthur, and pick up two bottles of wine—one I would drink with the girls and the other with the band. Del Shannon and I once polished off a bottle in our dressing room.

Ronnie and the Comets folded after the manager, Laddie Simcanin, wanted a lifetime contract, and our lead guitarist, Dennis Maserkawitch, refused to sign.

It was around this time that a group of upstarts called Donny B and the Bonnvilles started to become successful in what was called the twin cities—Port Arthur and Fort William, later to be known as Thunder Bay. It was fortunate that the band manager, Al Smith, wanted to add a saxophone player to the band. They were an excellent band with an adult manager who worked with the YMCA. Al Smith knew how to manage, and the drummer, Lynn McEachern, was an excellent vocalist who knew how to MC as well. He could hold an audience’s attention with his rhetoric alone.

The band consisted of Donny Brown on rhythm guitar and vocals, Gary Kostyniuk, Joel Stapanski on keyboards, and Lynn McEachern on lead vocals and drums. It was about this time that I started to be a lead vocalist as well, besides being the saxophone player. The band was performing in the Fort William Gardens, and when I joined, we were the warm-up act for the Beach Boys. We played regular weekly dances at the YMCA and were the warm-up act for many stars of that era. The most memorable in my mind were when we were the band for six Jewish fellows from New York called Jay and the Americans. They showed up with just a guitar player, and he taught us all their songs. This was a pivotal moment because we became professional with the tutoring.

One of the guys heard Donny call Joel “Jewy,” and they dragged Donny into the washroom and threatened to kill him until we explained that we were like brothers and it wasn’t meant to be racial. We didn’t even know what racial meant. After that show, we went on to have a deal with the city, playing dances for three thousand kids every week and splitting the revenue. That continued until the city became greedy and decided they would make more money by using another band.

Our only real rival band was called the Fugatives, whose keyboard player was Paul Shaffer. Paul went on to fame and fortune as the musical director of Godspell, then Saturday Night Live, and later the internationally famous David Letterman Tonight Show. But at that time, the Fugatives did not have the following that the Bonnvilles had, and the Gardens’ dances were over in the next few weeks.

When the Gardens dances ended, we ended up negotiating with a coffee house called the Fourth Dimension. I had been hanging around with Neil Young for a little over a year, and we would go to this venue and watch the various acts. Neil was staying at the Sea View Motel, which was owned by Gordy Cromton, who had made millions with the Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise and owned both the motel and the Fourth Dimension coffee house.

Neil and I had written songs together, smoked reefers, and jammed on a regular basis for most of the year. As I said before I co-wrote ‘Helpless’ with him, although after he left, he has denied that it was written in Thunder Bay at the YMCA. I don’t know how I remember, but I can still see myself knocking on his door, and he answered by saying, “What a neat place, with the airplanes flying like big birds across the sky.” His room was facing the airport, and those words went into the song ‘Helpless.’ Later on, he conveniently even forgot my name, although I had my own chapter in his first biography, Long May You Run, written by John Ennerson.

I was with him one night at the 4D, as we used to call it, when Stephen Stills was playing a cherry red Gibson guitar, and Neil said, “Come on, Tommy, let’s go meet this guy.” For some reason I can’t explain, I told him I was just going to hang back and never did meet Stephen.

We had originally met Neil when he came from Winnipeg with his band, the Squires, to perform at a nightclub we played at on occasion called the Flamingo Club, a place that would play a big part in my life.

But first, back to the Fourth Dimension Coffee House. Since we had about 1,500 to 3,000 kids at our Gardens dances, we knew there was no way of fitting them all into the 4D, but they tried. It probably legally held 200, but it was so packed, body to body, that it took me 15 minutes to leave the stage and go to the back to get a drink. I was so overheated and thirsty, and the pop was served in little glasses, so I would get six cokes, down them, and go back to the stage and freak out to the music. People said I was on drugs, but I swear it was the six Coca Colas.

When I was sixteen, I auditioned for Buddy Knox and the Rhythm Orchids at the Colosseum. He had three million-selling records and was on top of the world. I met him later, and he recognized me. He said that I was just as good as anyone to join him, but he couldn’t take a sixteen-year-old to do what they were doing. Too bad, because I ended up doing that anyway, and he would have put me on top of the game. He had been drafted at the height of his career, gotten mobbed by women at the airport, ripped his clothes, and pulled out his hair when he realized there was no one to greet him when he came back from Germany three years later.

Buddy Knox was a broken man after that, and he moved to Canada, playing out his life performing in dingy, third-rate bars with put-together bands. Donny B and the Bonnvilles were at an all-time high, and we saved our money and hired Don Grassi and Chuck Williams, his assistant. They arranged for us to go to Hollywood to record with a producer by the name of Gary Paxton. Gary had sung and produced the Hollywood Argyles’ ‘Alley Oop,’ a song that was a hit in the ’60s. He had produced several million-sellers; one I can remember was with The Association.

Meanwhile, our lead guitarist, a fiery red-headed guy by the name of Gary Kostiniuk, told us that he was not going to California, as he had secured a great job at the newly formed Seaway Terminal and had a girlfriend with whom he felt he had a future. This was a great loss to us as a performing band, as Gary was an excellent soloist with antics and gyrations, and we would be left with Donny Brown as our only guitarist. While Donny was a great rhythm player, he was no soloist, so it slightly crippled us, but we decided to go anyway.

Ironically enough, Gary’s girlfriend left him after a month of him being a “regular” guy, and he lost his great job a year later. I always instinctively felt that it was better in life to head for the adventure rather than the safe route. And so, the Bonnvilles, along with Don and Chuck, headed to Hollywood on their next epic journey.

Landing in Hollywood: Dreams, Chaos, and the Spotlight

Upon arriving in Hollywood, Don told me that Gary Paxton had retreated to a golf course, and it was my job to get him to come back. I ended up in the middle of the golf course, where I saw a rather large red-headed, hippy-looking character dressed in paisley and sporting only a driver. I’m sure he was high on something or other, but after pleading with him for about half an hour and explaining the journey we had undertaken just to get him to practice our music, he agreed to come back and produce our session.

His setup was a bus for the control room and a garage for the studio. He had an arrangement to master the session at the Columbia Studio building, which was close by. Don and Chuck were essentially country music producers who had gained fame by discovering Loretta Lynn on Zero Records out of Vancouver. Being show business and all, Loretta left that part out of her biographical movie, a fact that Don never forgave her for.

Although Don didn’t know much about rock ‘n’ roll, he sure did know diction, and he tortured me for hours in the studio over pronunciation and diction. I have to admit that I was ready to jump in the pool and drown myself by the time the session was over, but I believe I benefited as a singer from that afternoon, for the rest of my life.

We recorded ‘We Were Meant to Be,’ a Paul Revere and the Raiders’ take-off I had written, along with a song entitled ‘Love and Obey,’ both of which can be heard on YouTube today. It has taken me years to listen to some of the songs I wrote because it feels embarrassing to hear the childish lyrics from that era.

When we recorded ‘The Face of Time,’ a song written by Ray Dee (Delatinsky), a friend and radio personality, and myself, Gary flipped out. He told us that he knew a hit when he heard one and said, “Go back to Northern Ontario and wait for stardom to come down on you.”

I sang the song and added a recorder break and some saxophone. It was the beginning of the psychedelic era and the start of a new wave of music.

Before we left, we decided that “The Bonnvilles” was too placid a name for a band of that time, so the new name was “The Plague,” and we had a big puke sign painted on the van that said, “The Contagious Sound of the Plague.”

Upon reaching Hollywood, we drove down Sunset Strip at night, and the streets were all lit up. I seem to recall there were twenty people deep on both sides. I have no idea why I did it or what prompted me, but I reached my hand out the window and gave the peace sign. Everyone cheered, and it was like a gigantic wave up and down the street as people cheered and gave me the peace sign back.

Just at that moment, we were outside a little place called “Pandora’s Box,” and a fellow said, “You’re a band, do you want to play in our place?” We pulled over, unloaded a few things—my sax, guitar, and bass—and went inside.

The first thing I noticed was the strange smell that I later got to know and love, but at that time, I had no idea what it was. The second thing was the band who were playing there at the time, called World War Three. They had no recognizable features because they all had hair down to their knees, with only their noses sticking out of their faces. Believe me when I say, us boys from Northern Ontario had never seen anything like this before.

We proceeded to set up our equipment and played one of our well-established songs that Lynn McEachern sang, which we had learned from “Jay and the Americans,” called ‘Only in America.’ When we finished, you could have heard a pin drop. I don’t think anyone in that place recognized that song as music.

I quickly told the band to play ‘Bo Diddley.’ It was a song I got from watching Ronnie Hawkins at the ‘Le Coq d’Or Tavern’ in Toronto. Well, that did it, and the place erupted. I remember jumping around on stage and seeing the marquee on the club across the street reading, “The Doors, live at the Whisky a Go Go.” I’m sure they were there that afternoon because later, when I listened to their version of ‘Bo Diddley,’ they used the same arrangement I had done with our band.

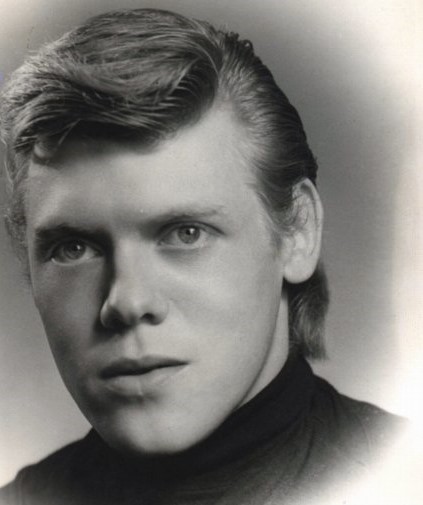

The picture of Tommy in the ’60s was done in Hollywood, and I was amazed at how much better it was than any promotional pictures done in Canada. Hollywood had the jump on the rest of the world for audio/visual.

After a week or so in Hollywood, we were changed for the rest of our lives in terms of musical tastes. This did not prove to be advantageous when going back to Canada, which had not caught up with the latest trends—but more on that later.

We drove across the Mojave Desert and were being cooked by the heat. At that time, we didn’t know about air conditioning and saw vehicles with their windows up. Desperate, we tried that, and of course, it made it worse.

We managed to get to Las Vegas, and with only rolls of nickels between us, we visited our first casino in old Vegas. After all of us had lost the last of our money—except for Joel, who had devised some system—we were all escorted out and sent on our way.

Once, we pulled over for a bathroom break, and after getting back on the road, we discovered that we had left Lynn behind somewhere in the desert. We backtracked for about fifteen minutes and found him standing at the side of the road in his shorts.

Ray Dee had become our new manager at this time and was too proud to tell the rest of us that he had run out of money and hadn’t eaten for three days. I always managed to have money, although I don’t know why or how, so I bought him a milkshake, and we continued on our epic journey.

I was brought up to be overly conscientious and law-abiding, so imagine my concern when Joel had purchased a Hammond B3 organ and wasn’t going to declare it at the border, and Don Grashey had insisted that we smuggle twelve hundred albums into Canada.

I was a nervous wreck by the time we reached the border and can’t imagine what that van smelled like with six people traveling basically nonstop for three days. When the customs officer poked his head in and said, “Let’s take a look in the back,” Brown’s head came rolling out. He tucked his head back in and said we could go.

All that worrying for nothing has been typical for most of my life.

So, we are back in Thunder Bay, waiting for fame and fortune, and bitten by the psychedelic influence of Hollywood and the Doors. We are performing at the Flamingo Club and the Fourth Dimension, and along comes Neil Young and the Squires.

Donny and I were always interested and hung around all the musicians who came into our city. The Bonnvilles, aka Plague, were the big success among all the starving bands vying for success. Many bands from Winnipeg, such as Danny Holmes and the Orphans, became friends.

I remember Grant Smith from Grant Smith and the Power coming to Thunder Bay, along with McLean and McLean, who originally showed up in blue tuxedos with a group called the Viscous Circle. I met John Kay from Steppenwolf, who told me that he would never be playing in a shithole like this again. He was referring to the Parkmoynt Hotel, better known as the JR, and he was right!

I met Rolly Greenway, Lancier Riel, and Kelly J from the Ascots, later to join King Biscuit Boy and Crowbar.

But of all of them, the most successful and disappointing was Neil Kenny Young. He was like a character out of The Lord of the Rings, almost a shadow figure. He was not very happy and was devastated when his parents split up. He was living at his mother’s place in Winnipeg when he first came to Thunder Bay and played at the Flamingo Club with his band, “The Squires.”

We got together and jammed on the fifth floor of the Twin City Gas building in the middle of the night. In those times, we would be up all night and sleep all day.

Lynn was concerned about security, whereas I couldn’t care less about day-to-day matters. I was encouraged to make my own way in life and have always viewed the next day as a new adventure.

I believe that the greatest mistake we made as a band was getting an agent and heading into the nightclub market. In my opinion, we were where the music industry made money in the concert one-nighters, but the boys wanted security, and we signed with the Billy O’Connor agency and set out to embark on a musical career.

As I recall, just before we left, The Face of Time was released on Crusader Records, the same label as Doby Gray. I got a call that Dick Biondi of WLS Chicago loved it, and we were on our way to success. The next day, I was told that Crusader Records was going bankrupt and that there would be no support from the company, which meant that my success was over before it began.

We started our nightclub tour, and Ray Dee, our new manager, came along with us. Our first job was at the Welland Hotel in southern Ontario, and I remember four things that happened. I wrote ‘Wendy Taylor’ with Ray Dee and Donny Brown, which we later recorded and released. It’s on YouTube, and I never liked it and still don’t.

I remember learning a song by Question Mark and The Mysterians called ’96 Tears,’ so the year must have been 1966. I also remember that the band, who had an immaculate reputation, had a water fight on the last night and almost flooded the place.

I remember that the people hated us, and between that and the water fight, we were almost fired. Our second job was a similar disaster, performing in Sudbury, and to add insult to injury, the mine was on strike, and everyone was in a terrible state.

I recall a fellow in the audience reaching up to unplug Joey’s Hammond organ in the middle of ‘Honky Tonk,’ and Joey, who was five feet nothing but totally fearless, stomped his foot down and crushed the fellow’s hand.

The real reason the people were so hostile was that they were used to acts like Ray Hutchinson, who went around in a white tuxedo and a cane singing ‘To Dream the Impossible Dream.’ We were a full-fledged rock and roll group, playing up-to-date rock songs in a marketplace that wanted Hank Williams.

Billy O’Connor told us if we didn’t do better on our next booking, we would be fired. This was after he had told Lynn he could keep us working indefinitely.

I am a little chronologically challenged about a few of the events in time sequence. I hopefully will get to check it out with Ray Dee when I get back to Canada.

Our next job was in a little town called Rouyn-Noranda, Quebec, which was a primarily French-speaking community close to the Ontario border. We were later told that it was where all the criminals from Montreal went to cool off, and once a year, the town police car was set on fire.

On our way there, we passed a town called Swastika, and we all laughed and joked about what it would be like to perform there. We arrived in Rouyn and quickly found out the club we were performing at was the one that nobody went to. The place to go was a downstairs club, and the band there was called “The Shades and Shadettes,” a fantastic R&B band with a big Hammond organ sound.

We all felt it was the end of the road for us, but we set up and, to our surprise, we got an audience of more than twelve people. So we played like it was our last show, and when we played Bo Diddley, Lynn got so enthusiastic that he stood up from the drums and ripped off his shirt. Of course, we all went into a frenzy and ripped off our shirts too.

When we left the stage, the people were backing up away from us as if they were afraid. The next night, our club was full to the rafters with people, and we were both in our element.

Meanwhile, down the street, the Shades’ agent was calling them and asking what was going on up there. They told him there was a fantastic rock band playing, and nobody had heard anything like us before. We asked the Shades if they would contact their agent on our behalf, and we promptly received a call from the Harold Cutlass agency.

As it turns out, the Cutlass agency had about 70 acts a week traveling around the country. I believe the main headliner was Romping Ronnie Hawkins. The agency would tell the clubs what they were paying and tell the bands what was being received.

Harold told us that he already knew we were an excellent band, but what he didn’t know was what we were like as people. He would book us at his most difficult club owner’s place, and if they liked us, the agency would take us on. Of course, you might guess the place we were going to was The Red Pines Lodge in Swastika, Ontario.

We loved Rouyn, and the French girls were so accommodating, but the guys were not so friendly. Don and I were in a little restaurant called the Moulin Rouge. We were sitting there talking, having ordered a pizza, and looking through a window so covered with grease that you could barely see through it, when a couple of girls came up to us. After very little broken English, they agreed to meet us in our room at the hotel.

Filled with anxious anticipation, I eagerly ate my pizza when Brown said, “I don’t think those guys back there like us.” I turned around and looked, and the pizza got stuck in my throat when I saw about ten guys sitting at a back table, just glaring at us. Brown said, “I think we’d better get out of here,” and we left in a big hurry.

We scurried across the street to our hotel, and when we got to our room, the girls were waiting there. We invited them in, and were sitting on the bed talking when we heard a banging noise coming from down the hall. I quickly glanced out the door and was horrified to see a rough-looking guy banging on a door down the hall. To make it even worse, he was banging on the door with a gun.

I quickly pulled back, silently shut the door, and told everyone that it was a guy with a gun. The girls started crying, and just when I turned to ask Brown what we should do, I noticed that he was crying too. I stuffed them all in the closet and sat on the edge of the bed, waiting to die. But the banging slowly receded, and everything went quiet.

I later realized that he had missed our room because, typical of band rooms, it looked like a broom closet and there was no number on the door.

Being from my world of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, there was no place for violence in it, so I told the girls to leave. Feeling the safety in numbers, I slept on the floor in the big band room where everyone else was crowded into.

On another occasion, a waitress came up to my room and told me to run, that they were going to smash our equipment and come to kill me. Apparently, Brown had insulted everyone in the club by announcing that there was no such thing as the French mafia. By the time I came down, Brown had bought everyone drinks, and they were all swearing allegiance to us, telling him that we would be under their protection.

We heard a story about a band that had played there, and a couple of them were terrorized in the restaurant. One of the band members even pulled out a gun. That night, the club was packed, with everyone in the audience wearing a black suit. After every song, they all got up, clapped once, and sat down again. Needless to say, the band left town that night, followed by a string of vehicles that only turned around when they reached the Ontario border.

Joel, our keyboard player, was a brilliant musician, but he was five feet nothing and had an arrogant attitude and strut. One day, I wandered into the Moulin Rouge, and there he was, sitting and talking to the most beautiful girl I have ever seen. He was certainly no prize to look at, but was always with some awesome-looking girl. Of course, I found out later that the girl in Rouyn had given him syphilis.

Such was life on the road in the ’60s.

I remember being in Rouyn and having them throw a birthday party for me. I was sitting at the end of a large table with about sixteen people, all celebrating my birthday—most of them I barely even knew. If my calculations are correct, it was my 23rd birthday.

Then, off we went to the most difficult club owner in the world.

We arrived at the Red Pines Lodge in Swastika in the early evening, just as the last band was packing up. They were the Hillabrand brothers, who later owned Century 21 Studios in Winnipeg. Their first comment to us was, “This guy’s nuts! We were playing ‘Doubling in the Green,’ a fiddle song, and there were three ladies who were almost the whole audience. The ladies got enthusiastic and started clapping their hands, and the owner came over to them and told them if they didn’t know how to conduct themselves, they would have to leave.”

That was the introduction.

I’m sure he was an escaped Nazi commandant because that’s how he ran the place. We could only bathe on Saturdays, lights out at a certain time, and we weren’t allowed to use the bass drum. Donny found it so oppressive that he was digging up various roots and smoking them, trying to get high, but no one misbehaved or crossed any lines because we were desperate to get on Harold’s circuit.

We did such an impressive job of keeping to the rules that even though we got snowed in and there were only a sprinkling of customers, he held us over!

I know this happened, but I’m amazed to this day. The rest of the band left on a Sunday and drove back to Thunder Bay—about 740 kilometers—just to get away. I made the mistake of staying.

As time grew nearer to playing, he kept asking me, “Vherr iss t’ band?” I kept nervously replying, “They’ll be here any minute.” This went on for an eternity, and just at the 11th hour, in comes the band, on time for the show.

I learned that even though it was crazy to leave, it was even more insane to stay. That ended that ordeal, and we were firm with the Cutles Agency, performing with some of the highest quality acts of that time.

The only disadvantage was following Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins around—doing stellar business, but not making stellar money.

A fellow named Tony Lorin ran the Bridgeport Hotel in Waterloo. He used to meet us in our hotel when we came there and bring several bottles of wine. The place was huge, and we generated lots of revenue, but when we asked for more money after our fourth successful performance, we never went back.

At that point in time, we were not discouraged by the recording industry, where we invested thousands only to get back tens of dollars in royalties. To add insult to injury, we had to pay for sending out records for free to radio stations, who most of the time threw them in the garbage without even listening to them.

Still, despite the unfortunate failure of The Face of Time, we scrounged up our money and headed back to Hollywood to do another recording session with Gary Paxton.

I remember we hired a rehearsal hall, and down in one of the other rehearsal rooms, a band was learning and playing very impressively the whole Beatles album ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.’

The Gary Paxton we met this time could’ve been a completely different person. Gone was the fat hippie in paisley pants with long shaggy hair. The new Gary looked like a clean-cut college graduate, but he was enthusiastic and ready to cut hits.

I was later told a story about Gary that when he moved to Nashville, he had rehearsed an extremely difficult guitar passage. In order to gain respect from the musicians, he took one of the best studio session guitarists—who had struggled through the part—and showed him how to play it.

The next recording session went fairly smoothly, and this time, our prize song was ‘World of Dreams,’ sung by Lynn McEachern. Before we left California, we even had a worldwide recording contract with Warner Brothers.

Full of joy and enthusiasm, we made the ponderous drive back to our hometown, only to find out that Sandra, George Stevenson’s wife, had kicked Lynn’s wife, Sylvia, out onto the street. Sylvia was 21 years old with a brand-new baby, and Lynn went ballistic when he found out what had happened. Of course, George Stevenson had to defend the actions of his wife, and in the ensuing argument, I lost my Warner Brothers worldwide contract when Lynn quit the band.

Later on, I found out that the contract was given to Kenny Rogers.

Many years later, I was with Lynn on his deathbed, and he said Don Grashey should have held him to the contract because, being so young, he didn’t realize what he had given up. Ironically, Sylvia left Lynn for a drummer in another band, and Lynn never met his son until a week before he died.

Also ironically, when I was being interviewed for a magazine article, and George Stevenson was on the line, the question was posed as to why the band broke up. I said, “Should I tell them, or do you want to take this one, George?”

He said, “Go ahead,” and after I related that story, he said, “That didn’t happen that way. Lynn quit in California.”

I was completely dumbfounded, and when I reiterated the incident, he said, “Well, I’ll have to ask Sandra.”

I find it amazing that people will reinvent the past to suit themselves.

I could never forget being screwed by two women and not enjoying it, haha.

And so we say goodbye to Donny B and the Bonnvilles (aka, the Plague), and the next band to evolve was to be Lexington Avenue, which I formed with the remaining members minus Lynn McEachern. He was replaced on drums by Doug Muncaster, and George Stevenson was replaced on bass by a character named Peter Demian.

Peter was a wild man and totally extreme. I made the mistake of rooming with him on one of my more ridiculous arrangements. The hotel owner had said that whenever we got a week off, we could stay there free of charge. While that sounded like a great idea at the time, in reality, we were stuck in Barrie, southern Ontario, with nothing to do, and money was limited.

Peter brushed his teeth so many times that I told him I would kill him if he did it again. That was figuratively speaking, of course, but he could be the most irritating person I ever met. The more it bothered you, the worse he became.

One day, while we were having a discussion, Donny started talking about jerking off. Peter, of course, claimed he’d never done it. Donny went on a long speech about how good it was for you. About two days later, in the Genasha Hotel diner, which was packed with people coming from church service, Peter was wearing a Mexican serape and nothing underneath.

He said, in a very loud and boisterous voice, “Well, I did it.” Of course, we bit and asked, “Did what, Peter?”

He exclaimed, “Whacked my tack, spanked my pee pee, it was great!”

We all sank in our seats with embarrassment as he enthusiastically strutted out of the packed restaurant.

Peter was also a great showman, which we didn’t appreciate so much at the time. In the middle of ‘Bo Diddley,’ as it reached its peak of enthusiasm, Peter, having heard the McEachern story, would stop playing his bass, come out on the dance floor, and start dancing, climaxing with him ripping off his shirt. The people loved it, but we, being serious musicians, hated it when he’d stop playing the bass.

Another Peter story took place at a club called Harry’s Hideaway, a downstairs venue in Hamilton. It was a rough place where occasionally someone would be killed, but we were always respected because everyone enjoyed our music. Peter got to know some of the gang members, and one day, just like in the movies, he kicked in the door of the clubhouse and shouted, “Let’s ride!” The next thing you saw was Peter riding at the front of a long procession of motorcycles.

Years later, he joined a band in Detroit called the Happy Band. They were being featured, and the mayor of Detroit was coming to honor them. The only condition was that Peter would not rip off his shirt.

Of course, when the mayor showed up, the first thing Peter did was stroll up front, yelling, “This is for the mayor,” and ripped off his shirt.

The Lexington Avenue came to an end with me being alienated from the rest of the group. Donny went around in a purple cape, and Peter wore bizarre clothes that were weirding me out. I wanted to go home, so I called it quits and let it all go.

There are YouTube videos of the songs from The Plague and Lexington Avenue, and as of this writing, in my eightieth year, Peter Demian is still performing on Venice Beach in California to this day.

So I made my way back to Thunder Bay and started gigging in different bands. Occasionally, I would perform in Lynn’s band, and sometimes I’d put together a band with some of the friends I used to perform with.

Harold Bond was the original guitar player with the Nobles, the very first band I ever played with. Later, he changed his name to Mills after discovering who his real father was. He’s one of those perpetually youthful people who never seem to age. He loved music but never really cared about being a success at it.

I got a job at a club called Bunnies, and we put together a makeshift band that included Stan Forneri, our old drummer. We were frantically making up a list of songs to play, and Stan piped up, “I can sing Bobby McGee,” so we put it down on the list. Well, after we played the first set and did the song, I followed Harold outside. He said, “I have to smoke a joint. I can’t go back in there and face those people after Stan sang that song.”

I agreed—it was the worst version I had ever heard. Stan was one of those guys who never really got better as time passed.

I eventually got a job as the house band at that venue with Terry Erickson, aka ‘Doc Tibbles,’ on bass, and Tommy Cruikshank on drums. Doc is now historically known for having performed with Neil Young and the Squires, and he was a real character. He eventually ended up phoning John Lennon and booking himself into the Cavern in London to do a single as a warm-up for Gerry and the Pacemakers.

Meanwhile, back in Thunder Bay, my band was getting quite successful. The club had the uniqueness of having all the cops and robbers in the city gathering there. The police and undercover guys on one side, and the robbers and ‘bad’ guys on the other. They would pass notes and send drinks to each other. Of course, they all loved the band. Musicians, if they are accomplished, can travel across all social boundaries.

To me, music was my religion. I ate, breathed, and lived in it. Unfortunately, later when I attempted marriage, I found out how unskilled I was at everything else—but back to the adventures.

We played the club for a year, and somewhere in the middle of that time, I became Mr. Pickwick. Some waitress along the way decided that’s who I was. I’m sure glad the name never stuck.

When Terry left for England, I hired George Stevenson, the bass player from the Bonnvilles, and recruited Wayne Faulconer, a career musician who had come from Kenora. He was from a band called Satan and the De-Men, who had made a name for themselves in the Winnipeg market. Wayne was not only a great guitarist but also a showman, serious about his career in music.

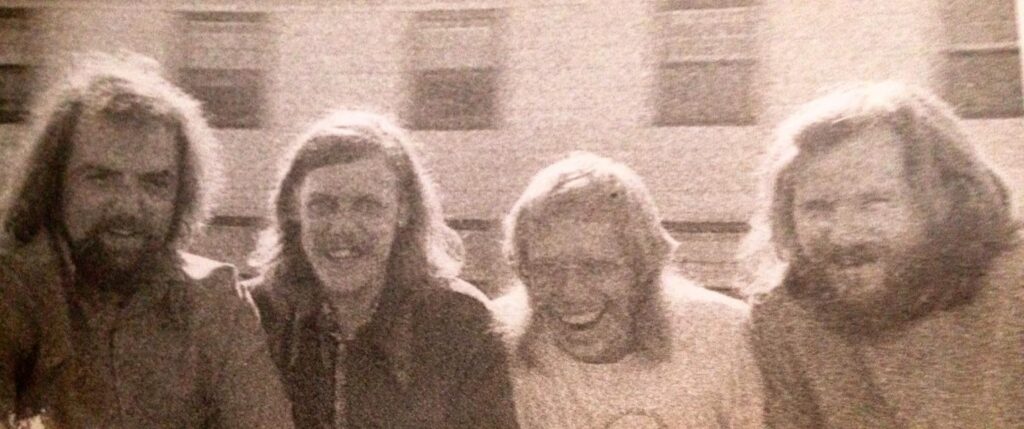

Tommy Cruikshank was a great drummer, and George was also an excellent bass player, so I had the beginnings of a great band that was to eventually be known as the Jarvis Street Revue.

After performing as the house band for a year, I was becoming specialized in maintaining success while staying at the same venue. One of the secrets was keeping the staff happy, because they were the first line of promotion. People would always ask them how good the band was. To keep the staff happy, it was essential to have a large repertoire and avoid repeating the same songs at the same time. Customers came and went, but the staff was there every night.

I’ve always been keen on rehearsals and sometimes enjoyed them even more than performances. Of course, when we rehearsed, the band improved, and so did the camaraderie. As a result, our regular customers increased, and our versatility grew.

I secured another house band contract at a rather skid-row venue called the CN Hotel. It was located in a seedy area of town, but it became a year of security and development. When Tommy Cruikshank went to load his drums in for the first time, he told me he was high on acid (LSD) and that there was blood and puke on the door. The CN Hotel was rough and very down-to-earth, but we had so many wonderful and happy times there with a lot of great people.

We learned every gimmick and happy song we could find—songs like Ray Stevens’ ‘Along Came Jones,’ ‘Guitarzan,’ and ‘King of the Road’—to keep the place light and cheery. There was a lot of drinking going on, and I had developed a routine of playing Boots Randolph’s ‘Yackety Sax,’ which became my theme song before Benny Hill captured it. In this routine, I would get everyone clapping their hands and go from table to table. I’d stop at a table, get everyone to count down like a missile launch, then take a glass of draft beer and chug it down. I became very proficient at this, moving on to the next table and repeating the process.

Sometimes, I’d get a conga line going and lead the huge line out one entrance of the building into another. There was one time someone counted seventeen glasses of draft I consumed during that routine, and I was still able to perform the show and say my name.

In those days, I’d do anything for the audience, but eventually, after a few years, I started questioning the idea of hurting my body to please others.

I mentioned that the CN Hotel was a rough place. One day, the government raised the price of draft beer by five cents, taking it from twenty to twenty-five cents. The customers did not appreciate this, and they were already extra inebriated and in a bad mood before we started performing.

As the show got underway, I was singing ‘Crying Time’ by Ray Charles, and George turned to me and whispered that there was a guy with a gun. At first, I thought he was just trying to impress his girlfriend by having it in his pocket. But when I looked around, I saw he was unsteadily pointing the gun at me. He was visibly plastered with alcohol, but he kept the gun aimed at me.

As I continued singing, You’re going to leave me, I couldn’t help but picture my body hitting the back wall from the impact of the bullet. Somehow, I had the presence of mind not to meet his gaze directly but to look all around him without connecting with his eyes. I instinctively felt that he wouldn’t shoot unless he saw fear in mine.

When the song ended, we all immediately jumped away from the stage and ran in all directions. The guy stood up and ran out the back door, where the police were already waiting and caught him. The gun was loaded, and he had just gotten out of prison. Apparently, because I had smiled at his girlfriend, he assumed I was the guy she was fooling around with. Of course, I smile at everyone in the audience and had never even met his girlfriend.

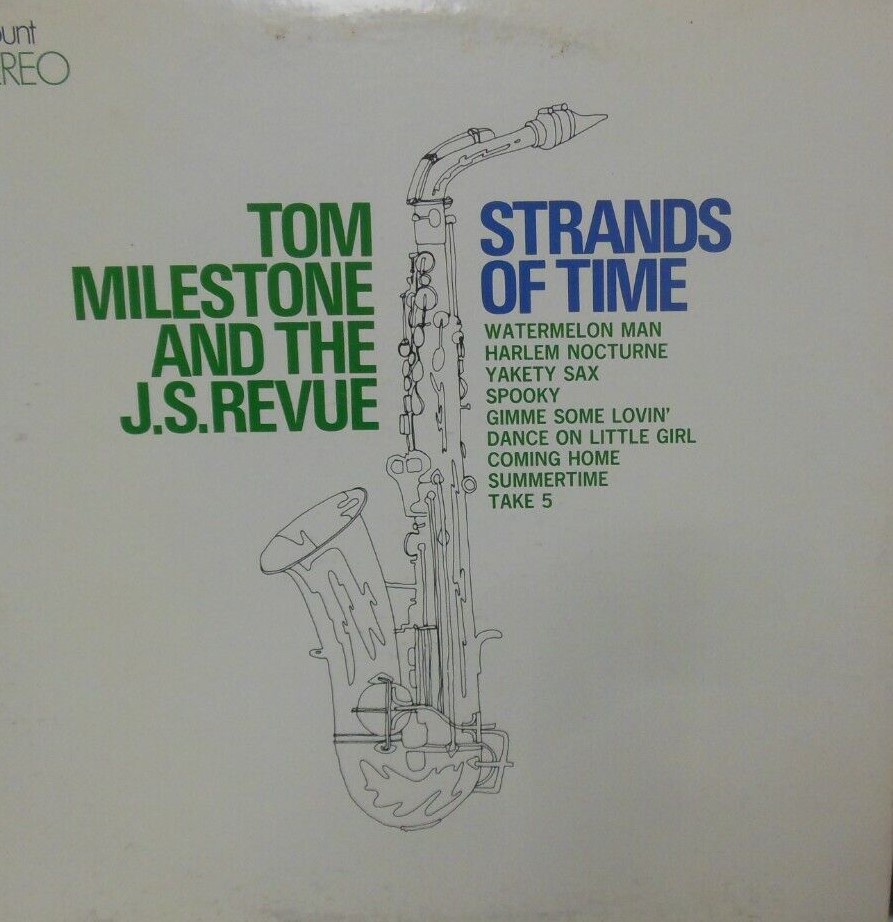

After a truly enjoyable year of fun and frolicking, we had learned every gimmick song imaginable and had run out of Ray Stevens tunes. Looking back, it felt like the ‘Wild West’ with all sorts of characters showing up together. During this time, I had become involved in building DMG Recording with Don Grashey and Chuck Williams, where I learned the craft of sound engineering and producing. It was here that I recorded my first album, ‘The Strands of Time.’ I’ve always been a bit ashamed of it because it was my first attempt, but it has since become a collector’s item, along with our iconic ‘Mr. Oilman,’ which once sold for a thousand dollars on eBay.

Eventually, I found myself at odds with the venue owners, who believed that New Year’s Eve was just another night, but I didn’t agree. New Year’s has always been a lucrative gig, and I took a job elsewhere. As the saying goes, that was that, and we said goodbye to the CN Hotel and moved on to greener pastures.

How the next chapter unfolded is a bit fuzzy, but it started with the owner of the Flamingo Club. We had a history, and he’d just gone through a rough patch. He had been in the hospital and developed osteomyelitis, which led to the amputation of his leg. By the time he got out of the hospital, he was half a million in debt. I met with him and gave him a reasonable price—six hundred a week for the band. That night, he and I drank every type of liquor from the bar, and although we were generations apart, we bonded over the evening and I felt like I had known him my whole life. He truly believed in me, and I didn’t want to let him down.

We played the Flamingo six nights a week, doing four 40-minute sets from nine to one, and rehearsed Monday through Thursday from 2:00 AM to 6:00 AM. After practice, we’d hit the YMCA to work out—lifting weights, running the track, ending with a steam bath—then home to bed by noon and up again in the late afternoon to start the cycle over. We did this for over a year, and no one ever missed a single practice. On Sundays, we’d go into the studio, sometimes not leaving until Monday.

One evening during this time, I got a call from the hottest girl I knew. She once walked across a stadium in a yellow sundress, and the whole crowd fell completely silent. She said, “Let’s get a room, a bottle of wine, and get sweaty.” I, of course, replied, “I can’t—I have to practice!” To this day, I regret that response. But since everyone was depending on me, and no one else ever missed practice, what else could I do?

Our practices were divided into three segments. From 2:00 AM to 3:00 AM, we worked on commercial songs like Evil Ways by Santana and Long Cool Woman by The Hollies. From 3:00 AM to 4:00 AM, we focused on music theory. I had an ear training course where we’d clap out rhythms or set the metronome to its slowest setting and punch out scales as loudly as possible. It was a tough but effective method that made for one tight band. After the theory session, we’d take a break, and Billy, our light man, would come from the kitchen with hash and sandwiches. Though I discouraged any drugs, Billy always kept things lively.

The Jarvis Street Revue

At this time, we adopted another unforgettable member of our crew: Gary Zaroski, or “Herman the Squirrel” as he was affectionately known. I first met him in the audience at the Flamingo, and his first words to me were, “I could kill you, you know.” I replied, “Why would you do that if we were friends?” Herman became a legendary roadie, his looming presence a force to be reckoned with. He was a large, bearded hulk of a man, and he earned his nickname when Mary Siroid discovered him in the Flamingo kitchen and said, “Get out of here, you squirrel!” Even now, all these years later, my heart swells with his memory. There was never a more devoted man or a truer friend than Herman the Squirrel.

In the first six weeks of our performances, we barely had any customers. I remember one night when a group of three or four guys walked in, and we got so excited just to have an audience. It was a humbling time, but we weren’t discouraged. We decided to build a stage and completely renovate the club. We painted the walls in a black and white checkerboard pattern, painted the ceiling black, and had our artist friend Bobby Kushner create a mural of us on the ceiling. We also installed black lights to make it glow in the dark. For the sound, we mounted Traynor columns on the ceiling to act as monitors and help disperse the sound. We did all of this without consulting Scott Shields, but his son was on board with our plans.

Scott, who was drowning in debt to the tune of half a million, gathered all his creditors and made them a deal: if they wanted to get paid immediately, he’d file for bankruptcy and they would all get nothing. But if they gave him time, he promised they would all be reimbursed. Scott was a likable guy, very charismatic, and his creditors agreed to his terms. That gave us the green light to proceed with our remodel, though Scott was a bit irked that we had gone ahead without asking for approval. Despite that, he kept his faith in me, and by the end of the year, we had lineups four blocks long with people trying to get in.

“‘Mr. Oilman,’ a tribute to the green earth and a stark reminder of the consequences of environmental abuse.”

Meanwhile, my recording skills were improving. After a year of working Sundays, we finally completed the epic album ‘Mr. Oilman,’ a tribute to the green earth and a stark reminder of the consequences of environmental abuse. I remember George Stevenson, who wrote much of the album, coming into the Flamingo at practice to convey how the songs should go. Wayne Faulconer, our guitarist, heard him out, then responded, “Don’t you hear it, man? It goes like this,” and belted out, “Mr. Oilman!” I ended up singing the main vocals on all the tracks, with everyone contributing to the background vocals.

There’s also the memorable moment with Tommy Cruikshank, our drummer. I asked him to play the drums with his hands, and he screamed at me from the control room window, “You’re fucking nuts!” I kept insisting, “Just do it.” After a long back-and-forth, he finally gave it a shot. When he heard the playback, he was amazed, saying, “Wow! That sounds great.” I remember feeling so satisfied, knowing that persistence really does pay off, and often, accomplishments are born from jumping through hoops.

After saving up our money, George and I scheduled meetings with major record companies in Toronto. We were confident, knowing we had a strong album and were seeking the best deal possible. When we met with the A&R producer from RCA Victor, he flopped down in his chair and said, “You have to tell me how you did this.” My secret was simple: he was limited to just a three-to-five-day recording session with a band at $150 an hour studio time, whereas I had the luxury of a full year of creative Sundays with no limitations.

All of the major labels were interested in us, but we ultimately chose to go with Columbia Records. The A&R representative, John Williams, was so enthusiastic about us that the deal practically sealed itself. However, I can’t help but feel that during this period, I made the mistake of a lifetime.

In those days, when you signed with a record company, you often gave up a lot more than just your rights to the music. Artistic control was usually taken out of your hands, and you’d hear things like, “You have to replace the drummer.” It didn’t matter if the drummer was the one who handled the bookings or kept the band’s finances in check; if he wasn’t pulling his weight musically, the label wouldn’t hesitate to make a change. The result was often disastrous for the band, and that’s something that I’ve always felt.

For me, my main concern was always artistic freedom. If you listen to the posts on YouTube of the Jarvis Street Revue, you’ll hear that we were all over the place musically, experimenting with everything. Despite the pushback from the fossil fuel industry—who probably didn’t appreciate songs like ‘Mr. Oilman’—we became an underground hit. We may have been as popular with the oil industry as the thirty-five mile carburetor, but we didn’t care. The oil industry was, and still is, the largest industry in the world, and they didn’t take criticism lightly. But I won’t dive into the ethics and greed of it all here; it’s already baked into the song.

The love affair between Columbia Records and the Jarvis Street Revue lasted for a few years until everything came crashing down with the dismissal of John Williams, the head of Columbia Records Canada and our biggest supporter. He was replaced by Bob Ezrin. I remember sitting in his office, listening to him pitch why he should be the new head producer of Columbia. He played me all his past recordings, bragging about producing ‘(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay’ by Otis Redding, and then—bam—things took a sudden turn. A week later, I wasn’t even allowed through the doors of Columbia. They’d decided that any acts who weren’t under contract had to go, and the new producer didn’t want any dirty dishes. He wanted a clean slate, and only if you were still under contract would they even consider working with you. I’ve always regretted not signing with them. It felt like a huge missed opportunity, but it’s also a clear example of how poorly record companies could function, and how much they often disregarded the artists.

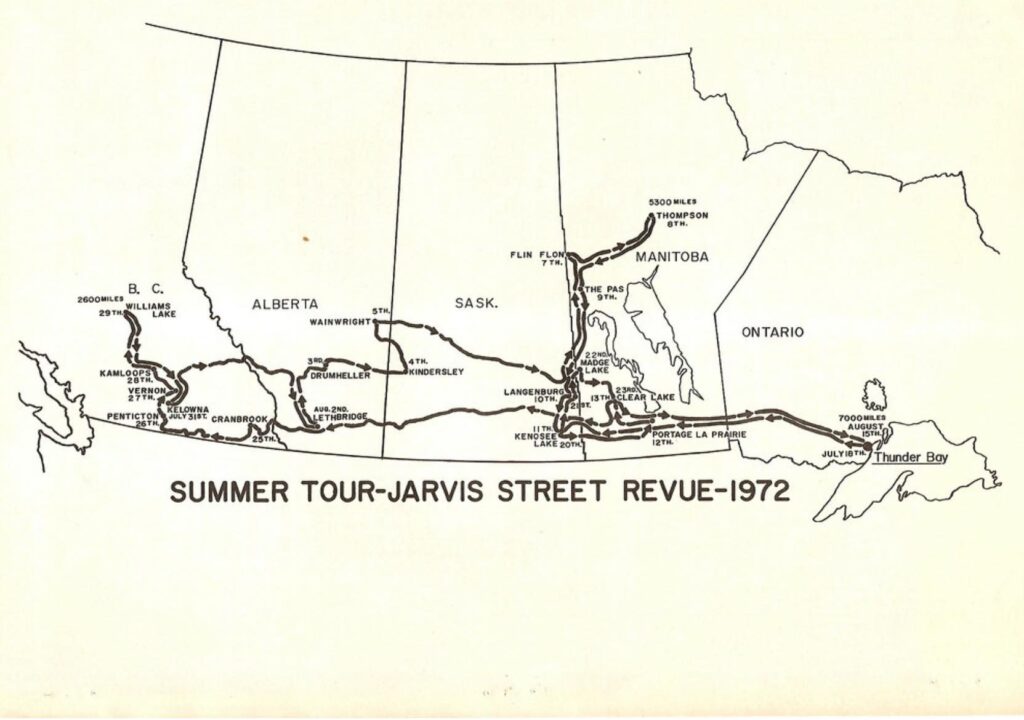

Around this time, we were also close with a promoter and radio personality named Greg Dempson. He suggested we go on a summer tour to promote the album, which was set to be released any day. The tour itself was a huge success, but it turned into a financial disaster. Tommy Cruikshank, our drummer, blew the engine on our touring bus, and the cost of repairs ate up most of the profits from the tour. After that, Tommy quit the band, frustrated that he hadn’t made any money from all the hard work. By the time we got back, the album still hadn’t been released, and the whole thing felt like a wasted opportunity.

Tommy Horricks

All photo materials are copyrighted by their respective copyright owners, and are subject to use for INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY!