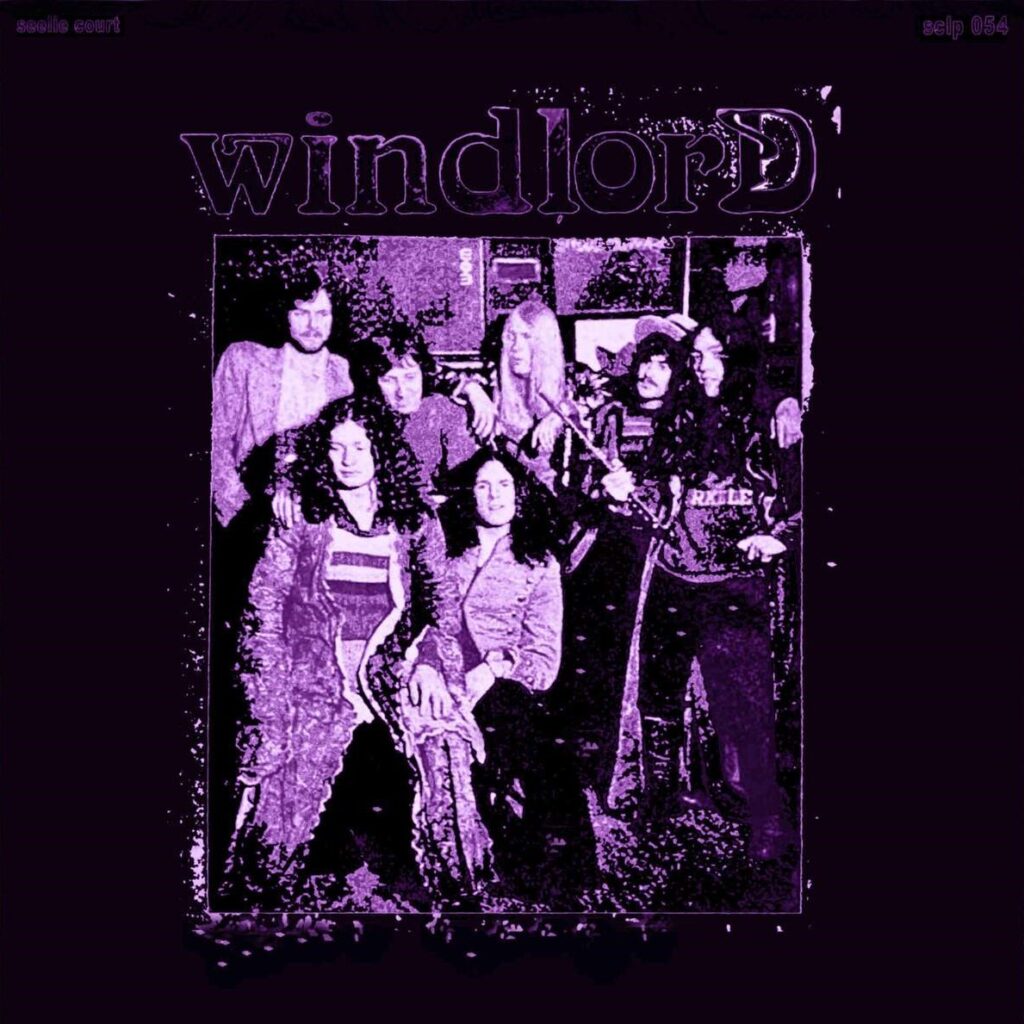

Windlord | Interview | The Secret Tapes of Windlord

Ah, Seelie Court, dredging up those golden threads of the past with their upcoming release of tracks from the elusive Windlord—each a flickering echo from ’72, with names that conjure whimsy: ‘Lady Heroine,’ ‘Julia Dream,’ ‘Lady of Easy Virtue,’ ‘Roman Roads,’ ‘Splodge,’ and ‘Willie the Greek’.

It’s a tale as old as time, a friendship forged in the sun-soaked chaos of Skegness, where Mods and Rockers clashed in epic tribal showdowns that could put any festival to shame. Picture it: a scrawny kid with a guitar, under the watchful eye of a jazz-passionate father, gleaning chords from old Burt Weedon books, the sound of summer sweetened by the camaraderie of youth and the bluesy influence of hippy mates strumming folk tunes on sandy shores.

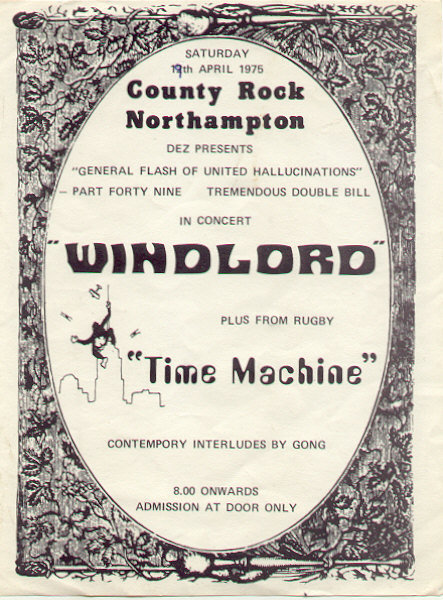

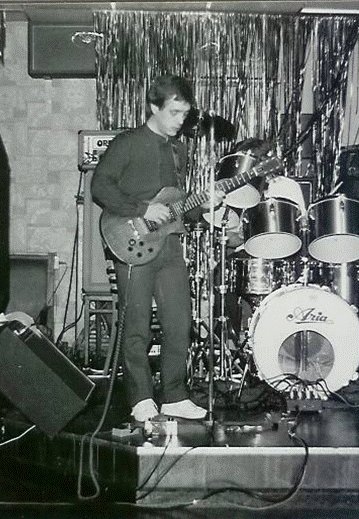

Those early days, a swirling vortex of ambition, led to gigs that felt like rites of passage—pounding out beats in a darkened youth club, the thrill of live performance crackling through the air like static. There was a sense of wonder as they navigated the local scene, from the basement jams with a motley crew of misfits to conquering the stage at the County Ground, where the light show dazzled and the sound was a living beast. And let’s not forget the legendary Melody Maker contest, where their original tunes fought for glory against rising stars, nearly clinching victory before being outshone by the quirky charm of Deaf School.

As the echoes of youth faded and life took them on separate journeys, the recordings of that era stand as a testament to an irreplaceable moment in time, a unique glimpse into the spirited chaos that was the Windlord story. Despite the ebb and flow of their musical pursuits, the passion remained—an undying flame that would eventually ignite again, decades later, reminding us all of the power of friendship, creativity, and the timeless allure of rock ‘n’ roll.

Immerse yourself in ‘Lady Heroin,’ a captivating taste of what’s to come from Seelie Court’s new release.

Windlord recordings will be out on CD coming out in about a month, while LP will be out in 2025 via Seelie Court.

“It’s a nostalgia trip back to ’72”

Are you excited about the upcoming Seelie Court reissue of your material from 1974?

Andrew Keightley: Yes, certainly, and amazed, really! It’s great that there is any interest out there at all. It was such a formative experience, and I’m honored to be a part of it. We were very young and somewhat naive, it being the first time in a recording studio for most of us. Although the original recordings were done professionally, there is little evidence of creative production or mixing techniques being used, and I think the old-school engineers were happy just to capture a flat EQ without clipping and unused to recording rock artists. It will be interesting to hear how it sounds remastered. Having said that, they give a good snapshot of those times, incredibly nostalgic for me personally.

Would you like to talk about your upbringing? Where did you grow up, and what was that like for you?

As the youngest of five in the Keightley family, the various musical interests of my siblings and parents created an incredibly diverse environment in which to grow. I was born in Skegness, Lincolnshire. Being a seaside resort in the ’60s, summer in “Skeggy” was always buzzing with crowds of tourists. Mods and Rockers would engage in battles with each other and the police. These epic tribal battles were replayed throughout the country’s seaside resorts, as depicted a couple of decades later in ‘Quadrophenia.’ Bikes and scooters were all over the amusement parks, the seafront gardens, etc.; sometimes bloody, but it just seemed like a great adventure at the time. In stark contrast, there was desperately little to do in the savage winters. Music from both these factions featured on the turntables at home. My brother preferred the Rockers’ Elvis Presley, Eddie Cochran, and Gene Vincent, while my sisters would play the music of the mods: Small Faces, Spencer Davis, The Kinks, and The Who. My mum, who was very supportive of my musical aspirations, liked big band swing as she had been a keen tap dancer in her youth and later would regularly play her beloved folk artists like Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, Donovan, and Leonard Cohen.

How did you first get interested in music, and what would you say were some of the early influences that got you interested in music?

I was about 9 years old when I first became interested in making music and had read through a couple of pages of Burt Weedon’s Play in a Day and learned a few chords. At home, there was a piano (a Kimble Minx), and there seemed to be other musical instruments around, including guitars brought back from Spanish holidays, bought after hearing guitar played live for the first time at a performance of flamenco. My older sister Gill had taken piano lessons and played fairly well, but her passion was painting. I remember her guitar-toting hippy mates visiting from Cheltenham Art College that summer, playing folk and blues songs. I was especially impressed by the fingerstyle picking techniques of Johnny Coppin, who later formed “Decameron” with other students and who became big on the UK folk scene.

I first met Martin Winning (Windlords saxophonist) in 1964-65 when I was 11 years old and living in Skegness, Lincolnshire, through a school friend. Although he went to a different school, we became good friends. Martin went on in later life to play sax with many of the greats, and there is footage on YouTube of him on stage with Van Morrison and Ray Charles! Martin’s dad was a guitarist who had played in big swing bands from his time in the services in Italy in the ’40s and ’50s and was devoted to fulfilling his fatherly duties by preparing his son for a musical career. This involved regular Saturday lessons lasting a few hours to get him through the grades. He took him through recorder, clarinet, and eventually to saxophone and flute. When I met Martin, he had begun playing clarinet and was already a confident sight-reader.

On Saturdays, I would turn up at his place and hang around, making a nuisance of myself until he had finished his lessons. His dad asked me if I played the guitar, and I said yes, of course. So Martin’s dad began to teach me enough so I could accompany his son. The songs were jazz standards, mostly Benny Goodman-type arrangements, which required me to learn some jazz chords played in a jazz “comping” style, lending me a copy of Mickey Baker’s Complete Course in Jazz Guitar. He was a good teacher, and soon he found a young drummer, Dave Linguard, to play with us, and soon we did a small gig playing these standards for a local pensioners’ gathering.

When did the decision to start the band come about?

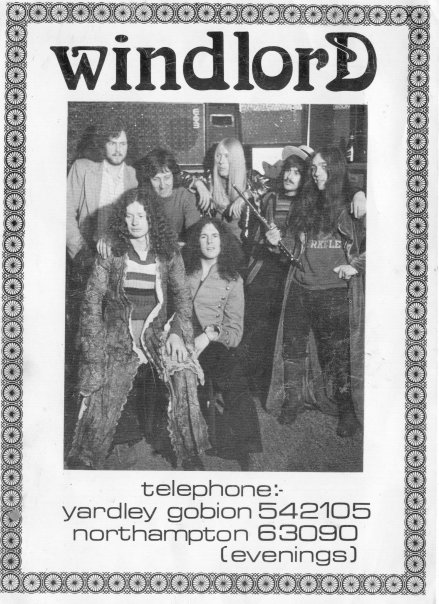

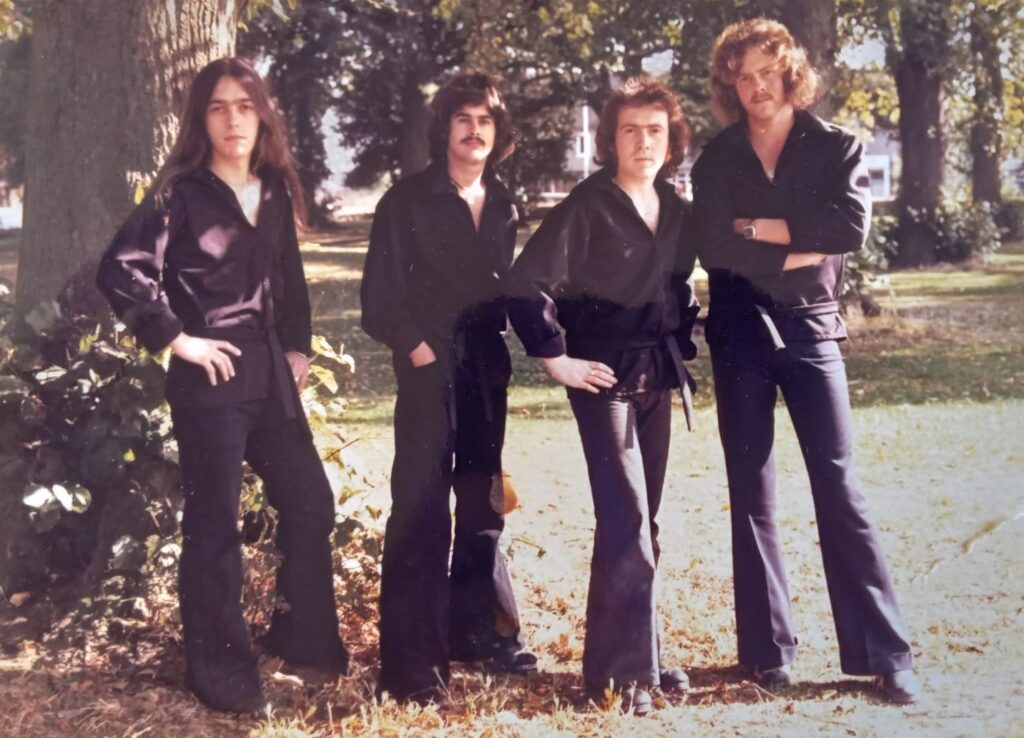

It happened in 1971, a couple of years after my family moved to Northampton when I was sixteen. Martin and I managed to stay in touch, and once I had met Steve Harvey and Steve Musgrove (Mussy), R.I.P., through school friends, who were keen to get me hooked up with other local musicians and form a band. Steve Harvey played drums and lived on a farm near Chapel Brampton, which had space in a barn attached to the main farmhouse that was ideal for rehearsals and became Jam Central. Rehearsals were mostly extended jams; all we needed was a vocalist and a bass player, and so through Mussy, we got bassist Shaun Farmer, or Billy Whizz, as we called him, because of his love of driving fast and vintage race cars. His dad had a carpet store, so he had access to the shop’s van. Things definitely went into another gear after he joined us; vocalist Steve Parish joined us soon after (or just before—I forget). “Parish,” as we referred to him for identification purposes, I remember was, as a youth and still is, an incredibly charismatic chap, tall, strikingly good-looking, with long flowing dark hair, who effortlessly impressed just about everyone he met with his vast knowledge of myths, legends, and general history. He could charm the pants off just about any female that came within his sphere of influence, spouting poetry and Shakespeare’s sonnets and, of course, making up lyrics on the spot.

I wrote to Martin and invited him to come to Northampton and join us. Steve “Mussy” at the time was playing guitar, and I was intrigued by his playing, as he had a much more rock and blues-based style and techniques than I had ever attempted at that point. We began album trading, featuring Brit legends like Jimmy Page, Peter Green, Eric Clapton, Rory Gallagher, and of course Hendrix, B.B. King, and Chuck Berry. Blues arpeggios, bends, hammer-ons, flick-offs, etc. I remember him playing Jimmy Page’s solo to ‘Heartbreaker’ from ‘Led Zeppelin II’ almost note for note! Although he later became an amazing jazz bassist, he had a great influence on my guitar playing. He was a valued friend, and although he could be fiery, I learned a great deal from him and miss him dearly.

Amazingly, Martin turned up in Northampton, and we soon found him a job and a place to live with Mussy at Jimmy’s End. It didn’t take long for him to seduce everyone with his incredible talent, and a creative surge began within the band, and the originals started to flow. Last to join us was percussionist Kip Shipley, who played congas, adding a great drive to the live sound immensely.

Were you in other bands before Windlord began?

No, apart from the Charles Martin Trio, Windlord was the first proper band. Interestingly, though, just before Windlord, encouraged by my friends, I did my first-ever paid gig. Unbelievably, it was with Northampton legend Allen Moore, now the globally renowned graphic novelist and author of “V for Vendetta,” “From Hell,” etc. He also attended Northampton School for Boys and was in the sixth form. After he spotted me playing guitar in my fifth-year classroom, he invited me to accompany him at this gig at Brixworth Youth Club, playing improvised guitar while he recited his poetry. We were paid 10/6d each! That’s 10 shillings and 6 pence each—22.5 pence in today’s money! I think he went on later to work with the Northampton band Love and Rockets, formed by the Haskins brothers, John and Kevin, after their band Bauhaus folded.

When was Windlord officially born? What’s the story behind the band name?

I guess it was around ’71 when Martin joined us, moving from Skegness. The Windlord name was definitely Steve Parish’s idea. It was from Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings: Gwaihir, the elvish for Windlord, the greatest of the Eagles. Typical subject matter for Parish, an avid lover of myths, legends, sorcery, and all things historical and mystical. This suited me, as I loved the Led Zeppelin songs ‘Battle of Evermore,’ ‘Ramble On,’ and ‘Misty Mountain Hop,’ which had been inspired by The Rings.

What was the scene like in your area and surrounding areas back in the 60s and 70s? Were there a lot of “hippies” and beatniks around?

It seemed like Northampton at that time was a wealth of young talent. Compared to Skegness, there were some good venues to see bands in the ’70s, like the Black Lion, Fantasia, The Country Ground, The Romany, The Plough Hotel, The Lamplighters, The Racehorse, The King Billy, and The White Elephant, where local bands could cut their teeth. The Nags Head in Wollaston would be a regular trip out of town to see bands where, amazingly, DJ John Peel would host events featuring signed bands on the national college circuit, like Wishbone Ash, U2, and Free. Also on the college circuit, of course, was Nene College, where we could catch these bands. This fertile environment later spawned bands of a younger generation, such as the Haskins brothers’ band Bauhaus and Escalator, featuring a young chap called Adrian Hutley on guitar (who later formed the band Portishead), with his mate “Coach” on drums.

As far as “hippies and beatniks” go, they were around, but they were more associated with my brother’s generation. During the Summer of Love in 1967, I would have been 14 and my brother 19 years old. So I felt I witnessed the fading of their ideals. In the ’70s, my brother left home to join a Divine Light Mission ashram in India to follow the teachings of Guru Maharaji. I stayed at home for the three-day week, strikes, and the winter of discontent. Although he came back with hepatitis, he remained true to his convictions his whole life. We didn’t even use the same expletives or superlatives, preferring “fierce man” to “far out.”

Later in the ’70s, in a band called Mad Dogs, we hosted a Monday night event at the Racehorse. We would charge on the door and do the first set, then feature a set by different bands every week. I think we ran it for about a year and it was quite influential in the Northampton scene. We had some amazing nights featuring regulars Escalator, The Eamon Malland Band (an amazing blues guitar player), and Freddy “Fingers” Lee (Screaming Lord Sutch’s old piano player), who would end his set by chainsawing his piano in half!

What did your repertoire consist of early on? Did you play a lot of shows? What are some bands you shared stages with?

Early on, as well as the originals, we played ‘Alright Now’ and ‘Wishing Well’ by Free, ‘Heartbreaker’ and ‘Immigrant Song’ by Led Zeppelin, and, weirdly, ‘Crocodile Rock’ by Elton John and ‘Blockbuster’ by The Sweet. We definitely had a quirky side. Looking back, we didn’t do many gigs, but the ones we did were pretty epic and enough to earn us a good local reputation. I only remember supporting Ducks Deluxe, Be Bop Deluxe, and Babe Ruth.

Tell us about your instruments, amplifiers, and other gear you had in the band.

I had a dearly beloved Gibson SG, which I bought from Funktion in Northampton and cost around £250. I played it through an Orange 120W Graphic Amp that powered two 2×12″ Orange speaker cabs. I don’t remember what I paid for them, but I visited the very first Orange retail outlet near Shaftesbury Avenue to buy them. I was looking for a 4×12 cab, but they couldn’t get one together for me to take away. Probably a good job, as I had to get it home by taxi and train. I believe the amp to be one of the first off the production line, as the ohm info, etc., was hand-painted by brush on its rear panel! As sad stories of the ones that get away end, the amp was nicked, and the SG was sold for £250 after a fall snapped the neck at the headstock. PA systems were begged, stolen, or borrowed by Shaun Farmer (Billy Whiz), who would nick my two 3x12s for monitors and find me something bigger for me to play through, like four elliptical Selmer speakers, which gave me the best sound I ever had on stage!

When did the band begin playing together and for how long were you together?

I think we started rehearsing in ’71 and it carried on until ’75.

Did you have a manager?

It was when talk of management started and things began to look serious that Windlord fell apart, really. Steve Harvey had a girlfriend, Kerry, whose father, Eric Lawe, who was a keen jazz enthusiast, became interested in the band—probably down to Martin’s jazz influences showing through. I think it was at his suggestion that we enter the Melody Maker Annual Folk/Rock contest that year. We won the first heat and went to the final, which was held at Coventry University. I think we played ‘Splodge,’ ‘Lady Heroin,’ and ‘Julia Dream,’ and narrowly missed winning, pipped at the post by ‘Deaf School.’ I am unsure, but I believe that it was at this point that Eric, Kerry’s dad, either suggested that we make these recordings or sponsored them at a local recording studio he knew. Also interested in the band was Jim Aitken, who was my future wife’s father. He had recently retired from the US Air Force and was eager to promote Windlord; he went on to manage Mad Dogs, my next band. There was talk of booking gigs up and down the country for a tour.

What would be the craziest show you ever did?

It has to be the time that we headlined at the County Ground. It must have been Shaun Farmer who was in the right place at the right time and got us in for our own gig with support from the London band “Time Machine.” I remember this gig starting our set with an original, never recorded, called ‘Heart Beat.’ With a complete state-of-the-art light show supplied by our mate Chris Barnard in readiness, Steve Harvey and Kip Shipley were alone on a dark stage pounding out the beat on drums and congas: “Lub Dup, Lub Dup, Lub Dup….” through the enormous PA. We would make our way from the back through the crowd, guitars in hand to the beat. By the time we got to the stage plugging in, we were almost in a heightened state (we probably were high anyway, to be honest). Expectations were through the roof as the stage burst into light, and we would blast out the first chords of the forgotten song. The gigs at that time were characterized by lengthy drum and guitar solos and Martin’s incredible sax solos, where his use of the CopyCat tape delay was a highlight. It was also getting a bit Spinal Tap on stage—Lord of the Rings and history references, long hair and gowns, even a pair of metal flake wellies. Shaun Farmer (Billy Whizz) was to leave the band around this point, and John Brasset joined us on bass. Shaun had a brief stint with Left Hand Drive, our local rivals, and Sean Tyla of Ducks Deluxe.

What were the circumstances surrounding your 1974 unreleased studio album?

I don’t remember much at all about the recordings except that they were made at a place called NSR (Northampton Sound Recording). I don’t think the engineers were used to recording distorted guitars and insisted we play quieter than we wanted. I was unable to get the guitar sound right and was frustrated with the short session. I can’t speak for the others, but needless to say, I was disappointed with the results at the time. In hindsight, I am glad that they were made, as it is a unique glimpse into that incredible time that I am so grateful to be a part of.

How many hours did you spend in the studio?

It seemed to be over very quickly—less than three hours, I guess.

Please share your recollections of the sessions. What were the influences and inspirations for the songs recorded?

Apart from the Led Zep and Lord of the Rings influence and other tracks, there was a fusion of jazz and rock at work in songs like ‘Splodge,’ where Martin’s influence came to the fore with harmony lines and guitar licks. Later on, ‘Willie the Greek’ revealed a quirky side from John Brasset’s early new age influences.

What was the songwriting process like for the band? What inspired songs?

Mostly, the songs came directly out of the jams at rehearsals. A lick or chord sequence which we played over and over while Steve Parish improvised lyrics. Sometimes one or a couple of us would suggest a song that had been worked on prior to rehearsal; these were either played as originally conceived or worked out between us, such as ‘Lady Heroine,’ which Mussy brought to us in its entirety.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

For me, listening to the tracks over after all this time, it is so evident that Martin’s skill shines out from the recordings while we were in the early first blossoming of our talent. Martin was already a mature player, demonstrating his versatility by playing with us.

Did you ever experiment with psychoactive substances like LSD at the time of writing the album?

Just smoked marijuana at that time.

Would you consider there was a concept behind the album?

Definitely not; it was put together on the back of an envelope, haha!

Was there any cover artwork for potential release?

There was no artwork; it didn’t get that far, haha.

What followed for the band after the album was out?

We broke up soon after.

Was there a plan to record more back then? Are there any unreleased material or material that you didn’t record back then but were newly written at the time?

No, unfortunately, there were no plans to record more. There were some jams that didn’t get far enough to record but were being worked on for performances, such as the previously mentioned “Heart Beat.”

Did any member participate in any other bands back then? Or later in the ’70s?

I went on to form Mad Dogs, originally with Steve Harvey, Terry Percival-Smith, Martin Winning, and Pete Garofalo. After they left, I reformed it and had a short tour of Germany, coming back to settle and get married. I did some recording with Jean Turk and played only semi-professionally from then on until recently. Martin played with almost everyone in Northampton in the ’70s, including Uncle Eric (Eric Whitehouse, local blues legend), Eamon Malland, and Pete Watkins with Early Times, Johnny Hates Jazz, Terrence Trent D’Arby, etc., before touring with Wang Chung, King Pleasure and the Biscuit Boys, Frankie Ford, and later with Van Morrison and John Martyn. He is now still working into his retirement with regular TV appearances at Ronnie Scott’s. Steve Parrish subsequently sang for Left Hand Drive and The Tyla Gang. Steve Mussy, after taking up bass, also played with most of the Northampton greats. John Brassett played with many bands and moved to France, becoming a singer-songwriter and painter.

What occupied your life later on?

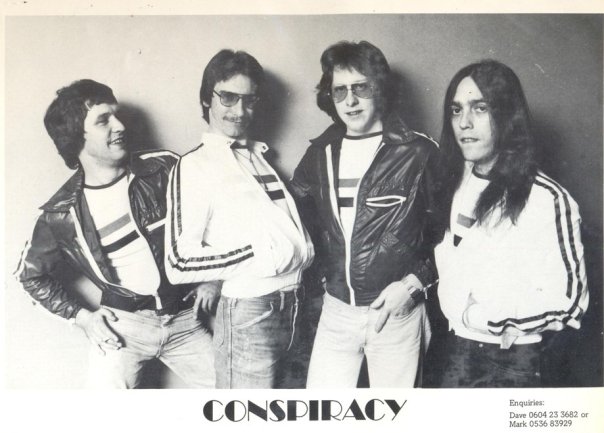

After Mad Dogs, I played with Conspiracy, a local band playing clubs and pubs semi-professionally with a mixture of Eagles, Poco, and other country rock classics before taking time out of music to run a furniture business.

Did you stay in touch with members all these years?

I lost touch with John Brasset and Steve Parrish but managed to keep some contact with Martin Winning, Steve Harvey, Kip Shipley, and Steve Mussy up until his death last year. RIP.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

I believe ‘Splodge’ was the last track to be written and showed the influence of Martin’s jazz background. It was perhaps the most progressive of the tracks. ‘Lady Heroine’ is also a standout track for me, typical of Mussy’s guitar playing—edgy and fiery! The most memorable gig was the aforementioned one when we headlined at the County Ground.

What are some of your favorite memories from Windlord and the ’60s/’70s in general?

My favorite times, besides the epic gigs with Windlord, were probably the early rehearsals at Chapel Hill Farm when we used to jam new stuff. Sometimes we’d rehearse with lights, strobe, and all, getting carried away with a few close friends. The friendships forged then endure to the present day.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style, and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

Blues players like Clapton, Peter Green, and Jimmy Page for their virtuosity—whose tone and licks I will continue to pinch forever. Jazz players like Django, Wes Montgomery, and Joe Pass for their mastery of technique and harmony.

What currently occupies your life?

Although semi-retired, I’m involved in several musical projects, including a party band, Blue Eyed Candy, and recording and gigging with an originals band, Dylan James and the Chapel Hill Gang, as well as a couple of duos: Dream Life with Sarah Rachelle Houston and S’Wonderful Jazz with Nancy Finch. I also run a rehearsal and recording space, CandyLand Studios, in Newquay.

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

Rock on!!

Klemen Breznikar