Couchois | Interview | Three Brothers, One Wild Ride (and a Few Bruises)

In 1979, a rock band from Huntsville, Alabama, called Couchois arrived with the kind of melodic ambition that fit snugly into the album-oriented rock era.

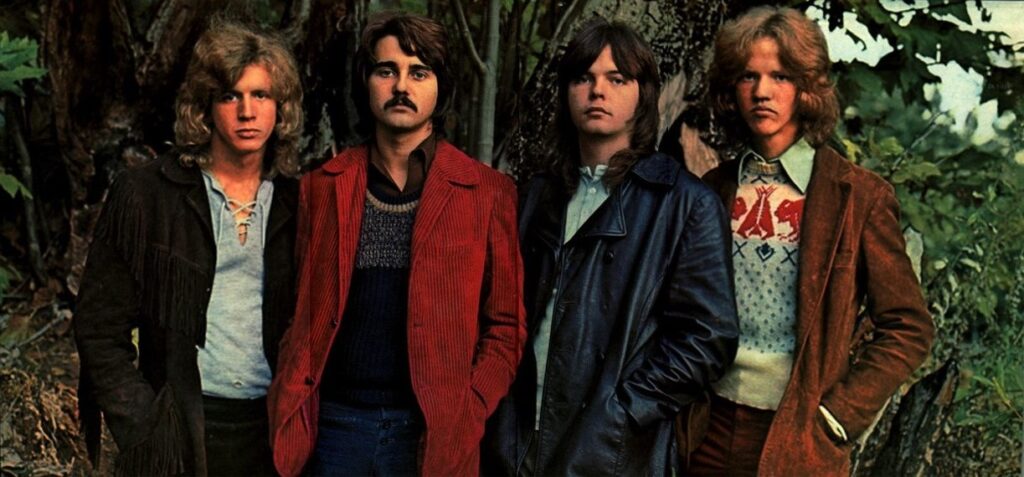

Built around the Couchois brothers—Chris (vocals), Pat (guitar), and Mike (drums)—the band was a family affair that channeled years of shared musical intuition into something fresh and radio-ready. Their self-titled debut, released on Warner Bros., broke through to the Billboard 200, hinting at big things to come.

The follow-up, ‘Nasty Hardware’ (1980), featured standout tracks like ‘Roll The Dice,’ a song that would live on through covers by Rage, Charlie, and John Verity. Early press was kind, with Billboard praising their “very melodic rock sound” and Pittsburgh Press calling it “enjoyable and promising.” But Rolling Stone took a more brutal stance, delivering a scathing one-star review that cast the band as “aggravatingly lame.” Momentum stalled, and Couchois quietly dissolved.

But Chris Couchois’s story didn’t end there. Before forming Couchois, he made waves in Ratchell, playing alongside ex-Steppenwolf guitarist Larry Byrom and bassist Howard Messer, sharing stages with the likes of Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Even after the band days were over, Chris stayed in the music world, writing and recording with the same passion that fueled him from the start. He collaborated with Eric Burdon and saw his work featured on multiple Burdon compilations.

In our recent talk with Chris Couchois, he laid it bare—the wild starts, the bruising stops, and the cold truth of what it’s like to get spun off the industry carousel. This isn’t some tidy rise-and-fall arc. It’s raw survival, soundtracked by stubborn hope, a brotherhood of riffs, and the kind of faith in music that doesn’t quit.

“There’s no question that growing up in the South gives a person a certain “feel” in music.”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Chris Couchois: We grew up in a French/Irish Catholic family of six children. My father, Bill, was an aerospace engineer, so we moved around the country every few years following his projects. He had also been a trumpet player for Woody Herman in his early days before he joined the Army Air Force during World War II. Our mother, Jane, was an actress who became very involved in the local San Diego theater scene, performing at the Globe Theatre and other large theaters around town. She was well-known locally and even had several newspaper articles written about her. So there were a lot of creative influences from our parents, and of course, we kids were very adventurous as well.

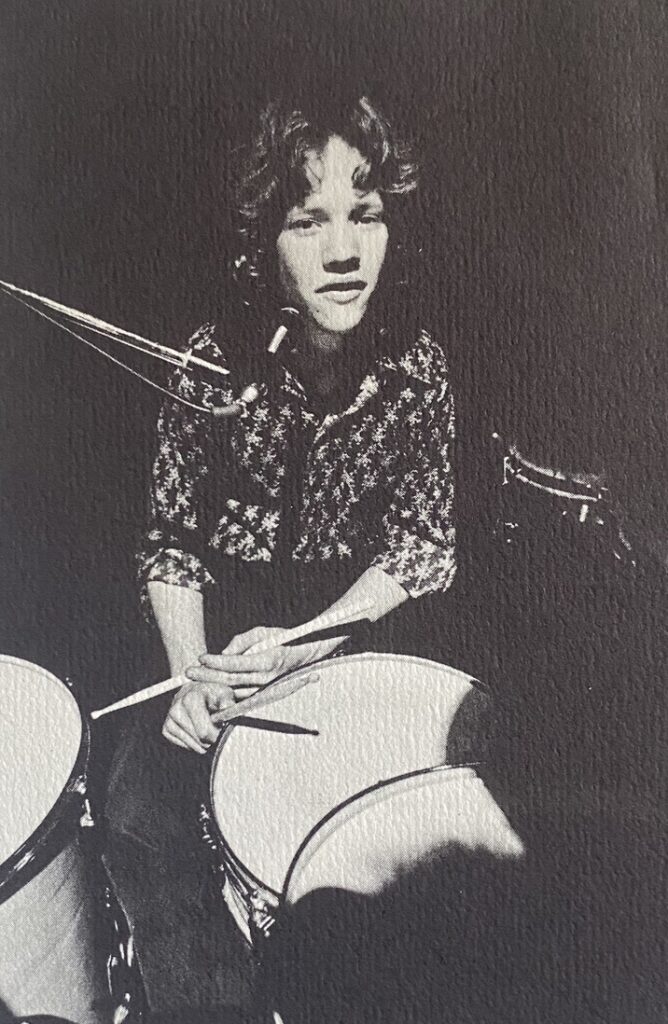

My brothers Mike, Pat, and I spanned a 6-year age difference between us, so we led very different lives in San Diego. But my brother Mike started playing drums and had his first taste of playing in bands in San Diego before we moved to Huntsville, Alabama, at the end of 1963. His band was called the Cavaliers and included a friend of his named Rudy Romero, who later became the guitar player/singer in the band The Hard Times. They had a hit covering ‘Fortune Teller’ and were regulars on the Dick Clark shows. Pat had started becoming a surfer before moving to Alabama, and I was a 10-year-old sixth grader playing with my dog in the San Diego canyons most of the time by the time we moved. Mike used to bring home the best music, and it’s where I first heard James Brown ‘Live at the Apollo’ and lots of other early soul music like ‘Up On The Roof’ and ‘Spanish Harlem,’ along with anything by Sam Cooke. When he brought home Stevie Wonder’s ‘Fingertips’ parts one and two, it really blew all of our minds. Even at that age, I really felt a connection to music. I would often experiment with writing songs as I went to bed at night, trying out melodies and throwing any words I could think of into the melody.

The brothers’ formative years really happened in Huntsville, Alabama, where we moved in November 1963, right at the time John F. Kennedy was assassinated. In fact, my mother and three sisters landed in Dallas the same day he was assassinated, on their way to Huntsville. The first things we saw of the South were the colored and white-only water fountains and the colored-only bathrooms. It was quite a shock coming from a pretty liberal California environment to see this segregation taking place. We learned the hard way that you had to say “yes ma’am” and “no ma’am” at school, but we soon got into the swing of things and thrived.

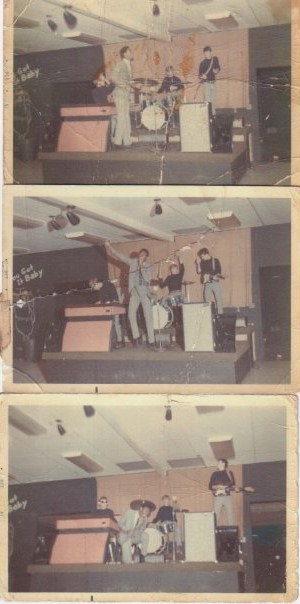

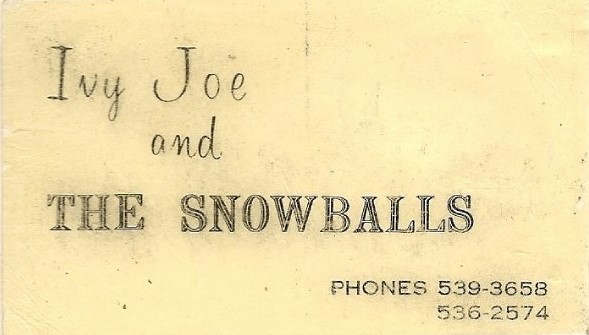

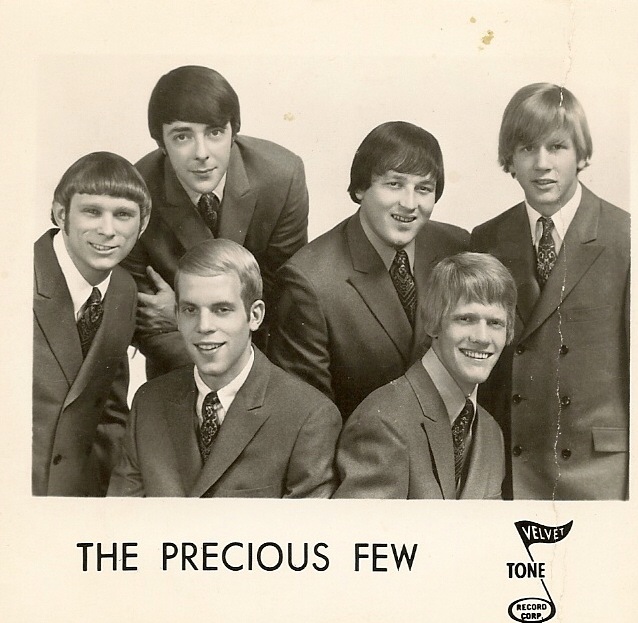

I started playing drums at 12 years old and was soon playing in bands. When the Beatles came on Ed Sullivan, everybody went crazy for this new music, and Pat started playing guitar. Mike and Pat started playing in bands too at that time, and over the next three years or so, we were in different bands, mostly not together. Eventually, Pat and Mike started a band called The Precious Few, and they recorded several records in Nashville. They were locally played, and they got quite a following from that. They also toured with the Dick Clark Caravan of Stars, among other things, and they enjoyed a bit of celebrity there. On the other hand, I began playing in local soul bands, namely one that was locally well-known called Ivy Joe and the Snowballs.

We didn’t record anything, but we were known as the first mixed-race band in Northern Alabama. This band is discussed a lot in Jane DeNeefe’s book Rocket City Rock and Soul, so more information is there if you’d like to know more. We played all the Sam and Dave, Stax Records, Booker T. and the MG’s, Atlantic Records, etc.—all the soul records of that time. It was a great foundation for me and something I’ll never forget. Of course, it was a little dicey as well, and we had some crazy times as a result of the race issues going on.

Pat and Mike’s band, The Precious Few, played lots of college gigs all over Alabama and Tennessee. They even opened up a teen club in Huntsville, Alabama, where all the local bands played. It was a great venue for live music. In addition, there were other clubs teens could go to. My bands mostly played nightclubs and some college fraternities. And yes, I was underage, but no one seemed to worry about that at the time. You might imagine what it might’ve been like for my long-haired hippie band to be playing country music covers mixed with Jeff Beck’s ‘Truth’ songs in country bars downtown. Crazy but exciting times.

Was there a certain scene you were part of, maybe you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

Of course, the 60s had the most incredible and ever-changing music scene of any decade I’ve witnessed. Having loved soul and the Beatles for a few years, we all transitioned to playing Jeff Beck, Cream, Led Zeppelin, etc. We grew our hair out, became a bit hippie, started smoking pot, and were part of the anti-Vietnam and anti-establishment crowd.

In the mid-60s, my brother Pat and Larry Byrom became friends. Larry was already a well-respected musician in the city, as he played keyboards, guitar, and trumpet in one of the most popular local bands, The Tics. When Pat and Larry got together, their love of The Beatles took over, and they formed a band called The Good Times to play a lot of that musical style. Larry had a brother named Michael, who was close to my age, and we started playing together in bands with him on bass and me on drums. I went over to Michael’s house one day, and there were Pat and Larry doing some rehearsal for their band. It was there that I met Larry. My first impression was that he was kind of nerdy in a clean, white shirt with thick-rimmed glasses and skinny as hell. But then Larry showed off his ability to play the famous Chet Atkins song that is both ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’ and ‘Dixie’ at the same time, and I understood he was incredibly talented.

I think it was 1967 when the Precious Few band was playing the Dick Clark Caravan of Stars that a group called The Hard Times from LA, which included Rudy Romero (Mike Couchois’s bandmate from San Diego), asked Larry to join that band and move to LA with them. So he left, and they recorded the first T.I.M.E. album with a single that charted, called ‘Take Me Along.’ Soon after, T.I.M.E. made some personnel changes, and in 1968, Pat was invited by Larry to join him and Richard Tepp and Bill Richardson. There in LA, they created a second album much heavier than the first one called ‘Smooth Ball.’ Great songs on that one, like ‘Do You Feel It’ and ‘Morning Come.’

By the end of 1968, Pat came back to Huntsville, and we started forming our own bands. Larry had been asked to join Steppenwolf, so it brought a close to the band T.I.M.E.. We had Mike Byrom on bass and played as much progressive music as we could find.

About the same time, I started hanging out at a friend of ours’ place we called The Shack because that house had seen better days. There were a lot of musicians who would come up to hang, and we would all jam multiple days a week. Anybody was welcome, and it was an ongoing kind of thing. My good friend John Huber owned the place, and he was a great guitarist always willing to play some music. It was one of the most important things I did to get so much practice in various genres and skill building. These were tumultuous times during the race riots, the political riots, the young versus old drama, long hair, and Vietnam. The Shack was a main hangout for like-minded musicians and hippies, so we would all go out to play touch football, drive out to the lake for a swim, and have late-night beer parties in the fields up on the mountains.

I would love it if you could tell us about Ratchell. There was a connection to Steppenwolf and T.I.M.E. How was this band born?

One night in the summer of 1969, Pat and I were returning home from jamming at the Shack when a song idea popped into my mind. It was the first time I ever had an original idea, and we went home and wrote a song called ‘Lazy Lady’ within an hour or two. That was the beginning of my singing and songwriting. We soon followed up with ‘Here On My Face,’ and I wrote ‘Problems’ later. Pat and I had been on tour with a band in 1970 where we played some of these originals, and the manager wanted us to record them, so we did. Pat sent the tape to Larry Byrom in California, and after a couple of months, Larry called to say he was thinking of leaving the Steppenwolf and wanted to start a new band. Larry flew into Huntsville in the last part of 1970, and we all spent a great deal of time jamming and playing together.

On December 27, 1970, I got in Larry Byrom’s rental car, which was a canary yellow Dodge Hornet, and we sped across the USA at very high speed to LA. Larry loved driving fast. We were finally caught speeding in Barstow, California. The officer made us sit on our heels in the back of the car with his gun drawn and scared the Jesus out of us. They threw Larry in jail and left me to ride with the tow truck and find a motel in Yermo, California. Before they took Larry away, he slipped me a $100 bill and gave me a phone number to call to come and get us. I got the hotel room, made the call, and within three or four hours, a couple of very pretty girls came to our rescue. I was barely 18, and that was my welcome to California.

A couple of days later, brother Pat flew in from Huntsville, Alabama, and we began staying at the famous Tropicana hotel. The plan was for Larry to keep playing with the Wolf while we put this band together and then give his notice once we got a record deal, so that’s what we did.

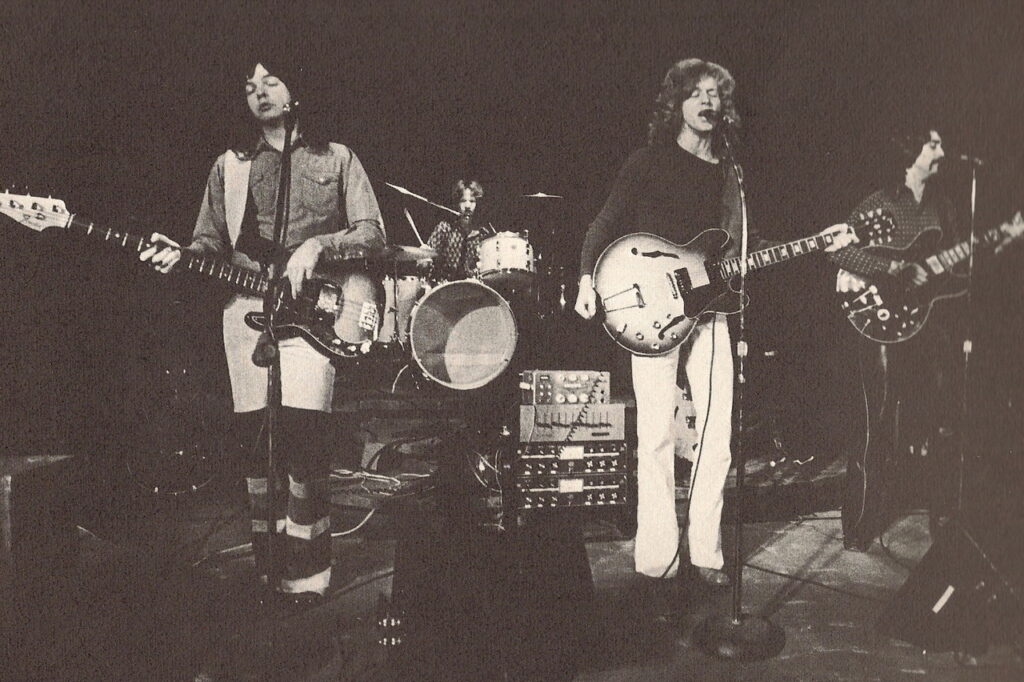

We moved out of the Tropicana to Malibu in Ramirez Canyon and began writing and playing together constantly. We had the songs Pat and I had written, and there were also several that Larry had written that we would work on. But we still needed a bass player. Pat and Larry’s old friend and former bandmate Howard Messer had moved to California, and he became the perfect fit for the band, allowing us to have four-part harmony and do many styles of music. Our goal at the time was to have kind of a Crosby, Stills, and Nash-type sound that mixed acoustic music with heavier electric.

Once we got a management team, we started doing what we called “musicales” out in Ramirez Canyon and invited all the industry heavyweights management could find to listen to us. We would play our originals acoustically in front of an intimate crowd. Some notable attendees were Paul Rothchild, the Doors’ producer; Ahmet Ertegun from Atlantic Records; and Roy Hallee of Paul Simon fame. We eventually decided to sign with Decca Records under the MCA label and started recording our first album in Wally Heider Studios with Larry Cox as a co-producer. Interesting fact—Joe B. Maudlin, who was a member of Buddy Holly’s Crickets, was our tape op for the album. He had lots of great stories, and he was a great guy.

But we ended up having technical issues on the first album. Namely, the Heider studio was brand new and had not been tuned or balanced, and it was bass-heavy sonically. To add to that, the mastering of the album was not done properly and was a whole 10 dB lower than industry standard. Holy crap. We were too young to know about this and catch it upfront, so it was only known after all the printing and distribution of the albums came out.

“We were trying to experiment and see what might be our best foot forward”

How would you compare the first and second album?

I like the overall songs and selections from the first album more than the second album. I do think the production on the second album was better for obvious reasons, but it was a bit more of a grab bag of songs. We were trying to experiment and see what might be our best foot forward, and the experiment had mixed results.

What do you recall from working on your album?

It was my first experience in a major league recording studio and my first experience with a major label, and it was mostly great! It was also my first experience seeing a pro arranger (Ray Pohlman) bring in a string section and record overdubs to Larry’s instrumental called ‘Saycus.’ I learned about studio equipment, and I would say I learned about all the intricate and interesting processes that go into recording an album. The band was so rehearsed for the first album that all the basic tracks were finished in just a few days. Lastly, I fondly remember that Rudy Romero (remember him?) visited the studio on the night we were singing ‘Warm and Tender Love,’ and Rudy got out there and did a backing vocal for that. That’s Rudy singing “you drive me out of my mind.” Sadly, he passed away at age 35.

What led to the formation of Couchois?

It took a while for the Ratchell bands to end because we added horns and went on tour with The Grass Roots and the 1910 Fruit Gum Company after Larry left to go back to Alabama. Then we had a version of the band with Larry, Pat, and myself, along with Larry’s brother Mike playing bass, that never quite got off the ground.

Pat and I eventually started forming bands in the valley of LA and played local nightclubs. We went through a couple of different management teams, but eventually met Chris O’Dell, from The Beatles and Apple fame, who wanted to manage us. That was a pretty interesting time as it allowed brother Pat to meet and hang out with George Harrison and Eric Clapton, and we met some of the English crew from the original Apple label. We also did a lot of hanging out at the RATS rehearsal studio owned by Beatles road manager Mal Evans. In fact, it was there that we heard Toto rehearse before they ever had a record deal and where I got to sing, jam, and drink with Terry Reid, who is one of my favorite English singers. Although we did demo tapes and shopped things around, we were not able to get a deal out of all that. Chris O’Dell soon got busy with Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Review tour and eventually a Rolling Stones tour, so that relationship faded for a while.

Around that time, Howard Messer rejoined Pat and me, and we did well in the LA club scene. Then my brother Mike, who had been working as an employment recruiter, said he really wanted to get back into music. So we brought Mike in as a drummer, and I became the frontman. That was the very beginning of what would become Couchois.

While Pat and I did the majority of the songwriting, it was Mike and Howard who really had the personalities to help us get seen by people in the industry. Through them, we were able to get a few meetings with publishing groups, and we would perform live in their offices to show them our material. It was a pretty rough go at first. It was Howard Messer’s connection to our old publicist from Ratchell, Norm Winters, that helped us get back into the recording business. Norm had done all the early publicity for Elton John and Ratchell and was now doing publicity for things like Star Wars, so he was very connected to the industry as a whole. Norm got us a meeting with Interworld Music Publishing. There, we performed for Mike Stewart and Eddie Lambert, and soon we had a publishing deal with them. Mike Stewart worked his magic to invite all the record companies to listen to the band, and eventually, we played for Roger Nichols and Steve Barri, who were with Warner Brothers Records at the time. Steve and Roger liked the band, and we were big fans of both of these people. Soon, we were able to sign with Warner Brothers Records.

You started playing music together in junior high school in Huntsville, Alabama. How did growing up in a city with such a distinct Southern vibe influence your early music? And when you transitioned from Huntsville to the national stage with Couchois, how did your roots shape your approach to rock and roll?

There’s no question that growing up in the South gives a person a certain “feel” in music. You normally think of it as a laid-back feel, but it’s also more about simplicity and what fits in the groove. There are so many really great players who are unknown in the South because Southerners just love playing music, regardless of making it or not. But there’s another aspect of our history that makes it a bit more of yin and yang for us players. Soul, and by extension Southern music like the Allman Brothers, was one end of the spectrum, and the other was the Beatles and English pop, with a very different sensibility for chord structures and harmonies. We ended up with a blend of both, I think, but focused a bit more on the pop side, with a good laid-back feel throughout.

Chris, Pat, and Mike – you three brothers were the core of Couchois. Can you elaborate on how the sibling dynamic impacted your songwriting and recording sessions? Did familial bonds create a unique creative synergy or occasionally lead to explosive conflicts?

At that time, of the three of us, Pat was the best musician. He was able to come up with great chord structures and lead guitar riffs to support ideas that I would generally come up with. I focused on melody and lyrics and the beginning ideas of songs while I learned to actually play guitar and piano and catch up with Pat. I was the more creative brother, I would say. Mike was the big personality of the three of us, and everybody loved Mikey. He could always tell a great story to anybody in the business or in the audience and engage with people far better than Pat and I. We got along very well together because of those differences. I can’t remember ever having any kind of bad arguments with either of them.

In Ratchell, you worked with Larry Byrom and Howard Messer before forming Couchois. How did your experiences in Ratchell influence the sound and direction of Couchois? Did you bring any specific elements from Ratchell’s music into your new project, or did you consciously try to distance yourself from that earlier work?

Working with Larry and Howard was a great learning experience in many ways. Larry was the most intelligent musician I’ve probably ever worked with. He played multiple instruments well and was very knowledgeable about music theory, setting a very high bar for other musicians to play to. He had also been famous with Steppenwolf and set a lot of the music direction for that band after he joined, so he had a lot of “cred” and respect from everyone. Howard was very creative musically but was also very music-business focused, which was something very foreign to me at the time. I learned a lot about music business realities and how to deal with the business side from him. Of course, everything you learn you carry forward into your next adventures, and that includes Couchois band music. Musically, since I had co-written most of the songs from Ratchell, we still ended up with some of the ballads or softer side music from that time coming into the Couchois music, as well as harder sounds like Pretty Young Girls.

What are some recollections from the two albums you recorded?

For me, recording those two albums was the best experience ever. We got to record with some of the best session musicians out there and had producers who were incredible to work with. We wanted great sounds on the album, and who better to do that than Roger Nichols, the Grammy winner from Steely Dan fame? Steve Barri had been a hitmaker for years and was a songwriter as well, so he had all the chops needed to help us make a great album. Eddie Lambert was a music aficionado and knew all about great music. Plus, all three of them had great personalities, were easy to work with, and had great senses of humor. It made our work much easier to do. For the first time, I saw people in the music industry who were kind of “normal.” No crazy drug or alcohol experiences with them. It was very different from all of my earlier experiences.

We also got to bring in some session players like Jim Horn, Jay Graydon, Michael Omartian, Victor Feldman, and several more. Watching those pros and seeing what they could add to our project was a great experience for us. And since Michael Omartian was finishing the Christopher Cross album in the same studios, we got to know him pretty well. Michael is probably the most talented musician I’ve ever met and a very funny person as well.

With Warner Bros. backing your debut album, there was considerable industry support. How did that influence your creative freedom and recording process?

For us, Warner Brothers took a hands-off approach and let us create exactly what we wanted. They were a great company, except for the fact that they had so many artists. I remember Van Halen, Exile, and Dire Straits came out around the same time as Couchois’ first album, and it was tough to get the attention we needed to break through.

Chuck Findley’s guest appearance was noted as a highlight on your debut album. How did his involvement come about?

Well, we hired Jim Horn to do the horn sections on the album, and I guess Chuck Findley came along as part of that group. I wasn’t actually aware of him being there, I’m sorry to say. But one little story about Jim Horn: After he’d done all the horn parts for the scheduled work, we thought maybe we should have him do a sax solo on the song ‘Going To The Races.’ So he listened to the run-through and said, “No, you don’t need a horn on that.” But we insisted, and I think we got a marvelous performance that fit really well with that song.

What are some memorable gigs?

We were never a heavy touring band. One of the most memorable gigs for me was Ratchell opening for Emerson, Lake & Palmer in Texas. For some reason, we had the not-so-bright idea to start our set with our slow blues song ‘Think About Tomorrow’ and have me out front singing it while the boys played it acoustically. Now, we hadn’t played for a live audience in almost a year, and suddenly we were standing in front of 12,000 to 15,000 people. I had never sung as a frontman, even though I had played for very large crowds behind the drums. But this made me so nervous that I was shaking. I got through it, but it was very uncomfortable.

Playing the Nashville Pop Festival in 1969 was also very memorable. It was the first time I played for a sea of people. And kids were asking for autographs afterward!

What would be the craziest one?

Strange to say, but it happened with Ivy Joe and the Snowballs when I was a teenager in Huntsville. We were hired to play a truckers’ convention way out in the woods. We had just set up when suddenly a gunfight broke out just outside the building. People started scrambling everywhere all at once. We hid behind the amplifiers. One of the band members had the presence of mind to see a case of beer, so we grabbed it. Once we could tear down after the police showed up, we went and celebrated surviving the gig.

After Couchois, you moved on to work with Eric Burdon. How did the transition from band life to session work and songwriting for films influence your musical perspective? Tell us about that period of time.

By 1980, I had personally achieved burnout in the music business. In fact, when my publishing company offered to renew the contract for Pat and me, I declined. I had to concentrate on getting sober, so I was a few months into that when the offer to do the movie with Eric came up. It turned out to be a great experience, especially since Eric was playing a couple of our tunes in the movie, and playing in that band was a lot of fun. In fact, one of the tunes we wrote and rehearsed, called ‘Heart Attack,’ didn’t make it into the movie, but I saw that Eric Burdon recorded it live with Alvin Lee and Rick Wakeman, which I saw on YouTube. So that was very cool to see. Pat and I also did a couple of other movies during that time, and that helped keep me occupied.

What currently occupies your life?

It’s funny, but I fell back in love with music after about 1985 and have been writing, recording, and playing in live local bands ever since. I have no interest in making it successful other than trying to let people enjoy listening to the music. I went back to school, got my degrees, and went into information technology for 35 years.

An interesting aside on technology: when we did the first Couchois album, Roger Nichols and I became friends, and he invited me over to his house where he showed me all the great tech he had, including his computer, which almost no one had at the time. Roger was extremely intelligent, and he excelled at photography, engineering, scuba diving, and many other things. He showed me his drum sampling program that no one had ever heard of before. There were synthesized drum machines available, but not real drum sample machines yet. He said, “Listen to this.” He hit play, and a groove started with a set of real drums playing. He said, “The bass drum is Steve Gadd, the snare is Jeff Porcaro, and it’s my new drum program I call “Wendell” (the same machine credited on the song ‘Hey Nineteen’). And he noted, “You can’t have the drums play perfect time—you have to put in certain delays to make it sound human.” Well, I was gobsmacked, and I went out immediately and bought a little RadioShack computer to learn to program it and try to emulate some of what Roger was doing. I didn’t really end up doing that, but instead, I got into the whole computer programming realm as a profession.

I retired from IT work five years ago and have been enjoying that. I still write and record music and play in live bands. The primary band is called Amerigumbo, and you can hear the first album we did on Spotify, YouTube, and Apple Music. Check out a song called ‘Home At Last’ that Rocco Presutti and I wrote if you get a chance. The Couchois Brothers played live venues for many years in the South Bay area but much less frequently in the last couple of years. But I did record with Pat and Mike and the Couchois band a song called ‘Take the Time,’ which is also out on YouTube and digital music channels if you want to check that out.

Other than that, my wife and I like to travel either to Europe or across the country in our RV when we’re not at home. On my last RV trip, I was actually able to stop by Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and visit Larry again. We had a great visit, and it was nice to see him. We still speak fairly often.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

My memories of the bandmates, production team, and session players are my favorite parts of that era.

From the early writing days, I love ‘Lazy Lady’ because it was the first song I ever wrote, and I love ‘Here On My Face’ because it’s actually a great blues tune with a great piano solo by Larry. I also love ‘How Many Times’ and ‘And If I Will.’

From Couchois, I like some songs for different reasons. I like ‘Going To The Races’ for the chord changes and ‘Walking The Fence’ for its brazen pop-ish-ness! ‘Roll The Dice’ is also good and high energy. I also really like ‘Anywhere You Are’ since we used session players for the basic track—Michael Omartian on piano, Mike Porcaro on bass, Baird on drums, etc. And to mention it, ‘Kalahari Cattle Drive’—where else will you hear a song comparing a cattle drive in Africa to driving the crazy freeways of LA? And although I now see them as way too syrupy, I still like ‘Cripple’ and ‘No Longer Needed’ since they come from real events.

I also like several songs I’ve written since the time of Couchois and Ratchell with Amerigumbo, and some I haven’t officially recorded yet. But that music is probably better to talk about at another time and place.

Is there any unreleased material by your bands?

There are also quite a few songs that were written but unreleased by Couchois. Who knows, maybe we can get that done someday.

Klemen Breznikar

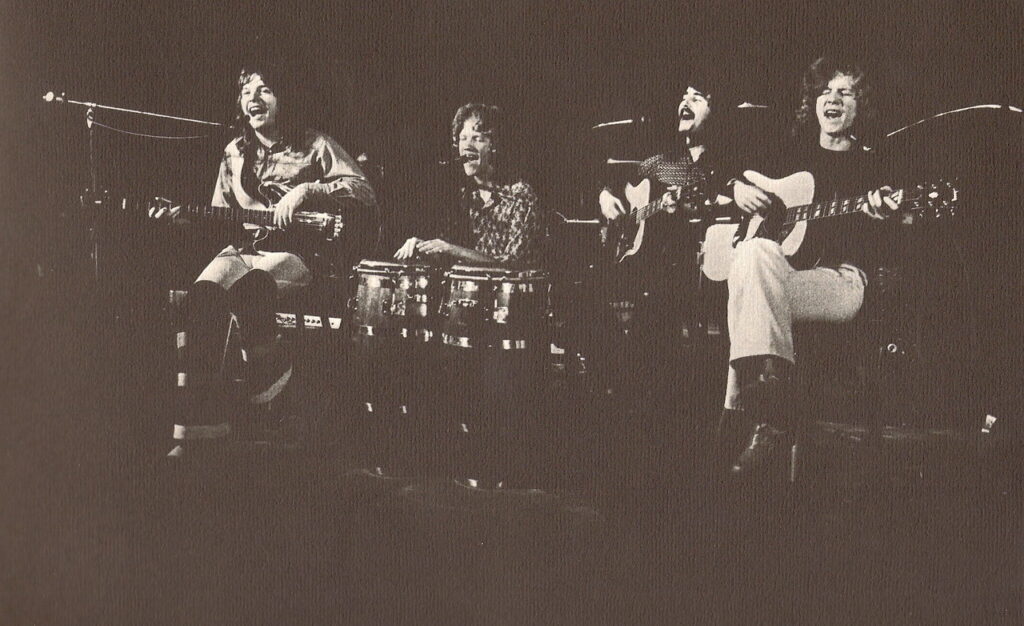

Headline photo: Couchois

Chris Couchois YouTube