Komintern | Interview with Michel Muzac on La Pop Sauvage

Michel Muzac’s La Pop Sauvage is a captivating and essential chronicle of the French underground music scene during the late 1960s and early 1970s, a time when revolution hung in the air, with high hopes and musical experimentation marking the dawn of a new chapter.

Through the lens of Komintern, Muzac explores a crucial yet underdocumented period. His book offers a deep dive into an era where music was inseparable from political activism, where light shows, comics, and theater coalesced into a vivid countercultural canvas. As Komintern’s story unfolds, it unearths an entire constellation of artists and movements—Red Noise, Ame Son, Lard Free, Gong—whose sonic experiments were guided by the same desire to escape the monotony of the old world. Yet La Pop Sauvage remains a unique artifact—self-published and beautifully crafted—designed to preserve this chaotic and creative time for anyone interested in what experimental rock music could offer. It is, in essence, the untold story of French musical resistance.

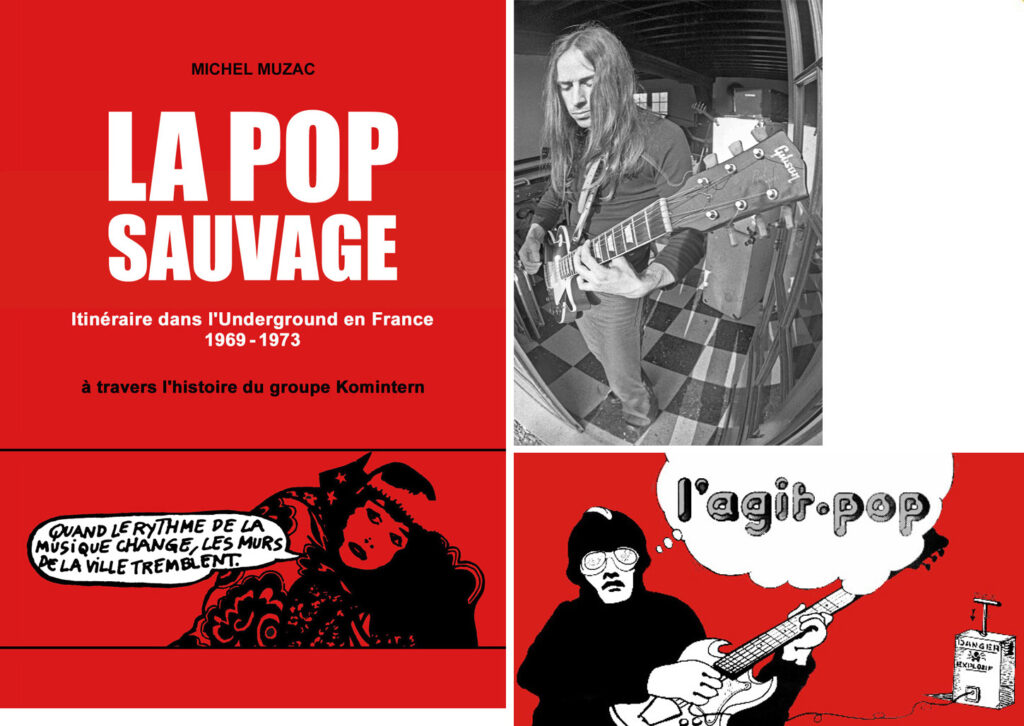

Book cover – Michel Muzac in spring 1972 (photo by Pascal Chassin) – Illustration on the back of the book

“An immersion into the French underground”

You recently finished writing a book about the Underground French Music Scene. Can you tell us more about it?

Michel Muzac: It’s an immersion into the French underground of the early 1970s (mainly from 1969 to 1973), during which I trace the history of the band Komintern, its journey filled with encounters and chance meetings, where you come across, among many others, Red Noise, Ame Son, Maajun, Fille Qui Mousse, Lard Free, and Gong. The musical aspect forms the basis, accompanied by a multitude of experiences: happenings, light shows, theater, cinema, dance, underground press, comics, etc., inseparable from the forms of expression that are free jazz, pop music, rock, and experimental music. I explore the many spheres and branches of counterculture because, indeed, while the musical underground, and more particularly its politicized side—which is the most significant, as it is inherited from the events of May 1968—appears as a French specificity, it is nonetheless part of a much larger movement, in which a very large portion of the youth in Western countries, whether involved in music or not, wanted to put an end to the old world and the prospect of a programmed, joyless life, organized around work and boredom.

Aside from a narrative written by myself, this book includes many press articles, testimonies, interviews, various documents, and photographs, all aimed at shedding light on the atmosphere of this playful and festive era, where Pop rhymed with revolution, agit-pop, and allowed the emergence of various liberation movements, alternative lifestyles, and all kinds of excesses.

Do you think it will be translated into English?

No, I don’t think so. It would be a monstrous task to translate, in addition to the text of this book, all the period documents it contains! However, given that the French musical underground is of great interest abroad, it might allow me to find an English-language publisher for it…

Indeed, this book remains, for now, completely underground, since I have been unable to find any French publisher (although some were interested) willing to publish it, and this for various reasons. On one hand, there are a lot of illustrations, many of them in color, which makes it quite expensive to produce. On the other hand, in the project I presented, the layout had already been done, which doesn’t suit publishers who prefer to design their layouts according to their own “graphic codes.” So, it was self-published by me with a limited budget, in only 50 copies, and therefore, it was little distributed. However, it has received very positive comments from everyone who obtained a copy and a few glowing reviews (Pierre Duur, then Dominique Grimaud (*) in Revue & Corrigée in June and September 2024, Eric Deshayes (*) on his website “neospheres”).

(*) Authors of the book L’Underground Musical en France (Le Mot et le Reste Editions – 2008 / reissue 2013).

“What made the French underground scene unique was its inventiveness”

Would it be possible to share a few sentences about the French Underground scene and how unique it was?

What made the French underground scene unique was its inventiveness, mostly stemming from the combination of two elements: first, the significance of May 1968, with the uprising of the youth and their aspiration to change the world, and second, its particular musical influences: Soft Machine, The Mothers of Invention, Captain Beefheart, Pink Floyd, etc. But also, more than in other countries, American free-jazz (for the good reason that many Black musicians, victims of racism in the USA, had found refuge in France, where they could freely record thanks to independent labels like BYG or Futura), and finally, the choice of the French language, sung or spoken, by underground bands to set themselves apart and avoid imitating Anglo-Saxon groups.

Did writing this book bring back any almost forgotten memories?

Yes, of course. Some of my memories were partial, not entirely accurate, or completely nonexistent on certain topics. I had to do a lot of research in periodicals and newspapers, as well as on the internet, and I also had to interview many people to ensure that my account was as accurate as possible: former members of Komintern with whom I am in contact, bassist Olivier Zdrzalik, guitarist Pascal Chassin, drummers Gilbert Artman and Michel Bourzeix, former members of other contemporary bands, particularly Alain Roux from Maajun, and especially the former manager of Komintern, Gilles Yéprémian, with whom I was in contact almost daily during the book’s creation. In fact, it was he who encouraged me to write it—without him, I would never have embarked on such a long and difficult adventure! All these fragments of memories combined helped bring to the surface what had been buried deep in my (our) memory.

Let’s start from the beginning. Where did you grow up, and what was life like back then?

I grew up in Paris, but I spent every weekend with my cousin Olivier Zdrzalik (future bassist of Komintern) at my uncle and aunt’s house, who lived in a suburban house surrounded by a large garden. Our childhood was carefree: we played cowboys and Indians, and I was usually the Indian. It was later, during adolescence, when we moved away from our childhood imaginary world and I found myself trapped in the constraints of studying, that the prospect of my future adult life seemed dull and grey. As I mentioned at the beginning of this interview, the dominant bourgeois society offered youth only a life organized around work and boredom. Music, which became a passion, was my escape.

Was there a defining moment when you realized you wanted to become a musician?

Yes, this defining moment happened during a family vacation in Spain. After dinner, a young guitarist was playing and singing in the hotel lobby, surrounded by young and old alike. It was some sort of revelation. When we returned, Olivier was given his first guitar (a classical one), and that’s how it all began. The playing became more serious: now that we had a real guitar, we stopped just mimicking rock stars with tennis rackets in front of the mirror!

So, it was by chance that I became a musician, but I never felt like a “professional” musician, having never studied music. For me, it was all about “Do it yourself!” I was carried by a wave made up of desires, encounters, and discoveries that led me to become one, simply armed with a guitar and electricity.

Did you have a close group of friends with whom you listened to music? What were some of the most important records that influenced you?

It was mainly with my cousin Olivier that I listened to music, along with some mutual friends, and we would spend evenings listening to everything from rock and blues to soul music. I also listened to jazz with my parents, who owned records by John Coltrane, Archie Shepp, Miles Davis, Pharoah Sanders, which we chose together, as well as ‘Messe pour le Temps Présent’ by Pierre Henry and Michel Colombier, with the track ‘Psyché Rock.’

At first, we were influenced by the Rolling Stones, The Who, Pretty Things, The Yardbirds, Them, and so on, and later, by Captain Beefheart, The Mothers of Invention, Soft Machine, King Crimson, Led Zeppelin… Among the albums that made a lasting impact on us, we can mention ‘Burnt Weeny Sandwich’ by The Mothers of Invention and also the album ‘Freak Out’ for its irony and its doo-wop reinterpretations, what Komintern will do later into their concerts by twisting a “yé-yé” slow song. We were also influenced by ‘Volume Two’ by Soft Machine, ‘Monster Movie’ by Can, ‘In the Court of the Crimson King’ by King Crimson, ‘Trout Mask Replica’ by Captain Beefheart, ‘Song of the Second Moon’ by Tom Dissevelt and Kid Baltan, an electronic music album with innovative rhythm breaks that influenced Olivier and me in ‘Bal pour un Rat Vivant,’ and ‘Hot Rats’ by Frank Zappa with violinist Don “Sugarcane” Harris… another rat story!

“Our music consisted of collective improvisations blending all our influences.”

Were you involved in any bands before forming Komintern? If so, what kind of music did you play?

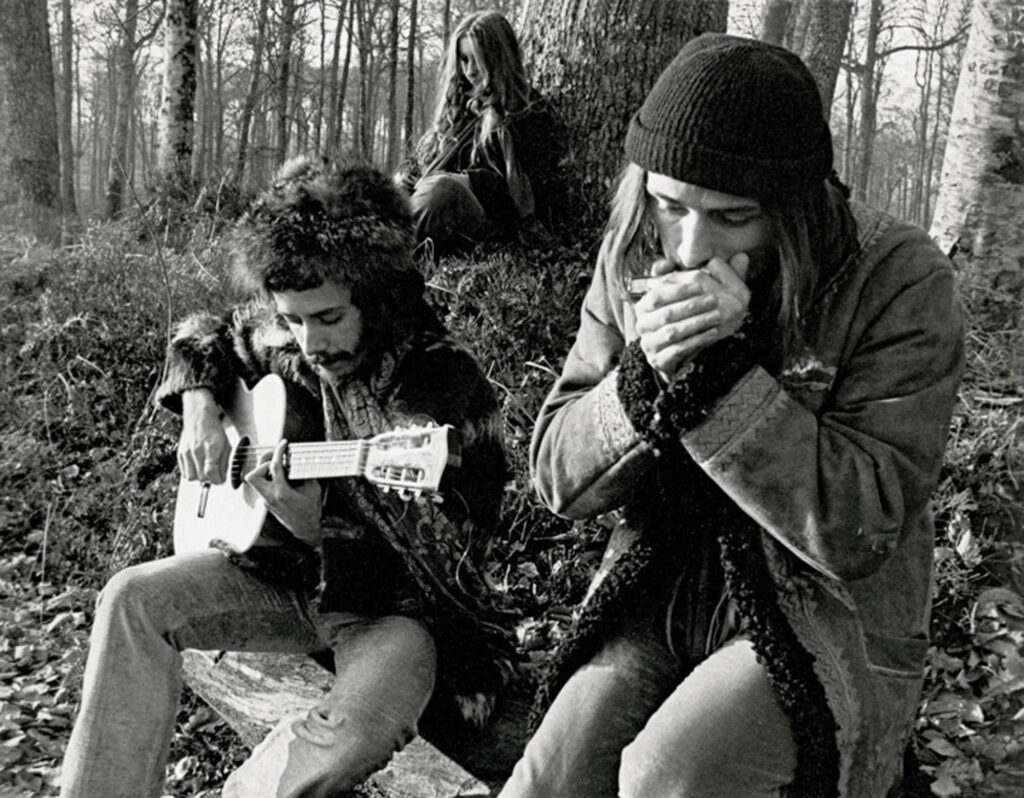

No. Before Komintern was formed, we rehearsed with three guitars: Olivier, myself, and Pascal Chassin, whom we met during a summer vacation in 1969 in Mallorca and Ibiza, which were underground hippie destinations, illustrated by the film More by Barbet Schroeder, released that same year, with a memorable soundtrack by Pink Floyd—a band that Pascal had as musical reference, along with The Doors and folk guitarists Bert Jansch and John Renbourn. Our music consisted of collective improvisations blending all our influences.

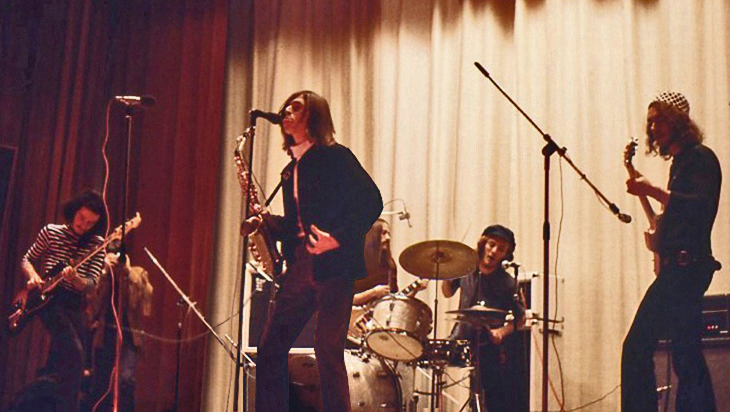

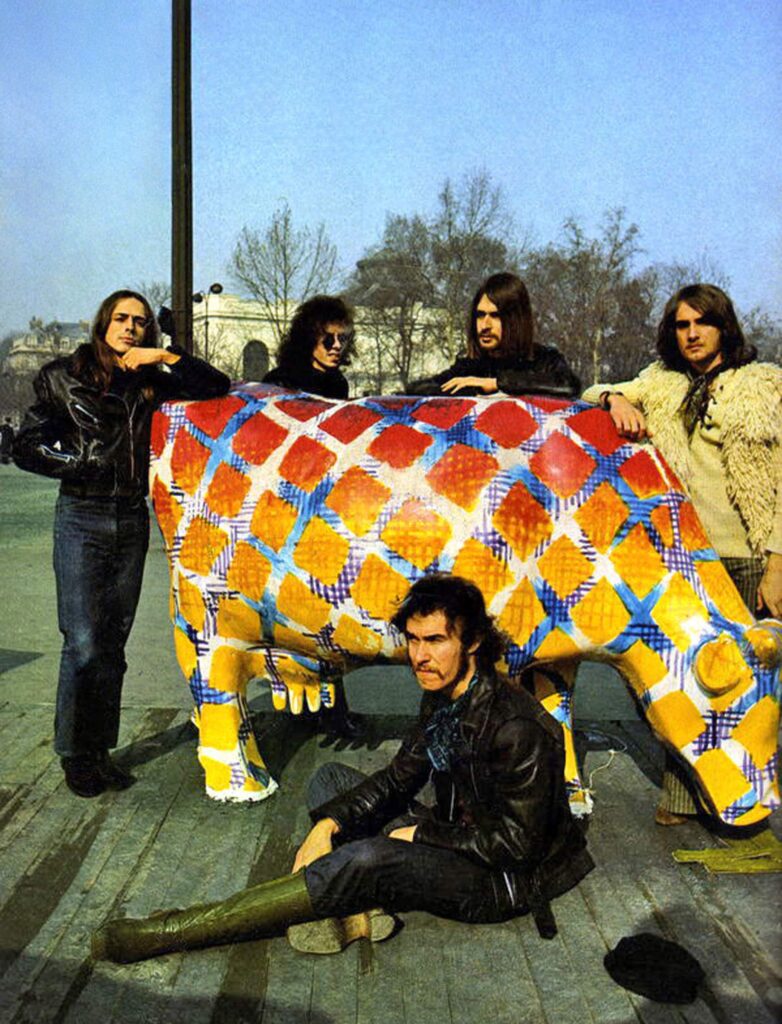

I believe Komintern was established in May 1970, featuring Serge Cattalano (drums), Francis Lemonnier (sax, vocals), yourself (guitar), Olivier Zdrzalik (bass, vocals, keys), and Pascal Chassin (guitar). Could you elaborate on the main concepts and ideas behind the band, and how this lineup came together?

For Pascal, Olivier, and me, after we started rehearsing together, the next step was to find other musicians to form a band blending pop and free jazz. We placed an ad in the Le Pop newspaper in late April 1970: “Looking for saxophonist and drummer to form a Free-Pop band.” Francis Lemonnier and Serge Cattalano, who had just left Red Noise due to musical and political disagreements and were urgently looking for other musicians for an upcoming tour, got in touch with us and came to meet at our rehearsal space. After a totally wild free-rock jam influenced by our respective musical references (Albert Ayler, Eric Dolphy, and John Coltrane for Francis, mainly Elvin Jones for Serge), we agreed to form a band together, and Olivier decided to switch to bass.

We were later joined by violinist Richard Aubert in the spring of 1971. He played both rock in the style of Dave Arbus in East of Eden and jazz in the spirit of Jean-Luc Ponty, bringing an acid-folk and “classical” touch to the band.

Regarding our concept and ideas: During the events of May ’68, Francis and Serge played, along with Patrick Vian (the group that would later be named Red Noise), within the iconic Paris faculty, La Sorbonne, which was occupied by students. On our side, Olivier, Pascal, and I were greatly influenced by the explosion of speech and revolutionary creativity during May ’68 with its graffiti and posters. For Komintern, it was about perpetuating the liberating ideas of the May ’68 movement through music, but also through speech.

It wasn’t long before Harvest signed you. How did that opportunity come about?

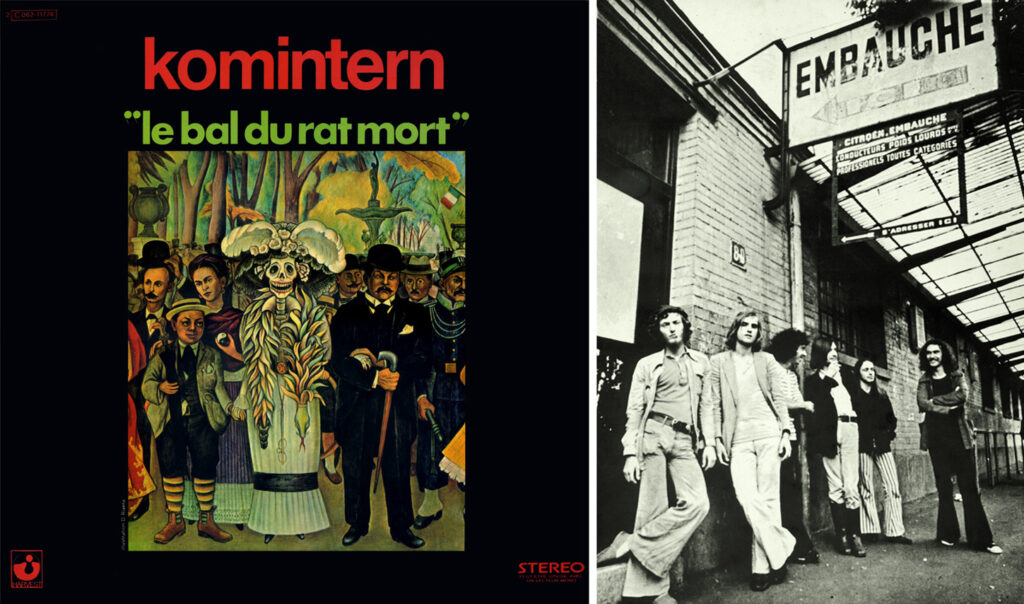

Francis Lemonnier and Serge Cattalano were already in contact with Philippe Constantin, the Artistic Director at Pathé-Marconi, before we formed Komintern, because of their upcoming tour opening for East of Eden in May/June 1970, a band distributed in France by Pathé-Marconi. So, Komintern started performing very quickly, after very few rehearsals. After this tour, Philippe Constantin continued to take an interest in Komintern, finding us concert dates, as did Etienne Roda-Gil, the famous French lyricist, who appreciated our anti-establishment and subversive side, having himself actively participated in the events of May ’68. Thanks to their support, we were able to record at Pathé-Marconi studios, and thanks to Philippe Constantin, the album was released on the Harvest label in November 1971, guarantee of underground legitimacy of which we were very proud, being the only French band to be released on a British label.

What’s the story behind ‘Le bal du rat mort’?

It was Philippe Constantin, the producer of the album, who chose the name “Bal du Rat Mort,” referring to Paris during the “Belle Époque,” when a group of people from Ostend (in Belgium) came to have fun in 1896. Among them was James Ensor, the famous artist, engraver, and anarchist. They found themselves at dawn in Montmartre, at a place called “Le Rat Mort” (a high point of late-century bohemian life frequented by Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine). The orchestra having already left, the pianist and a few dancers provided an unforgettable ending to their wild Parisian night. These adventures left such an impression that they decided to organize a philanthropic, masked, and costumed ball in Ostend, which was called “Bal du Rat Mort.”

Given that Komintern emerged during a tumultuous period in French history, how did the socio-political landscape of the early 1970s influence your music and lyrics?

In the early ’70s, the context was “electric.” State repression was strong, as was employer repression, which led to strikes and protests that often ended in violent clashes with the police. Prison sentences were handed down, such as in the case of the directors of the left-wing newspaper La Cause du Peuple. Even though we didn’t specifically have Maoist sympathies, we stood in solidarity with them against the unjust accusations they faced, and we expressed this on stage: “Free Le Bris, free Le Dantec.” During our concerts, Olivier and Francis would rally the audience, speaking out with protest texts that they either wrote or improvised, adapting them to the context in which we performed (universities, high schools, factories, whether on strike or not, festivals, etc.).

Komintern’s music, both wild, ironic, and parodic, sharply contrasted with the socio-political and cultural landscape of the time, which it fought, criticized, and ridiculed.

What do you remember about the studio sessions? Was there a specific concept guiding them?

The recording of the album, which took place in the large Pathé-Marconi studio in July 1971, went very smoothly from a technical standpoint. Recording with a major label offers advantages: adding brass, bandoneon, and the voice of a soprano to our compositions, and the various arrangements blended perfectly into the overall sound thanks to the magic of arranger Jean Morlier (who did very creative work, in line with the spirit of the band) and the sound engineers.

However, regarding our initial concept for the album, significant disagreements soon arose between us and Philippe Constantin, that altered our project and, especially, reduced it. He didn’t allow us to record the texts we had written, one of which was an introduction to the track ‘Hommage au Maire de Tours,’ and two others which were to be spoken without any musical accompaniment and dealt with work and commodities. We wanted to subvert the album by momentarily negating the music, which would have given it a completely different impact. These texts were all censored.

Who created the cover artwork for your album?

It was Philippe Constantin who chose the cover illustration. It is the central part of the fresco Songe d’une Nuit Dominicale en Alameda by Diego Rivera (the Mexican revolutionary artist and friend of Leon Trotsky), symbolizing a dying, decadent, and aging bourgeoisie.

We had a very different cover project on our side, created by a friend studying at an Art School. Based on a common idea, he adapted the cover of an underground US comic book magazine, Uneeda Comix, drawn by Robert Crumb, which depicted a crowd of small, diverse characters strolling through a street. Among them, a small rat holding a bomb, threatening to blow everything up, that he extracted from the set, and he made it say in a speech bubble “La Commune c’était la fête,” referencing the text “Sur La Commune” by Guy Debord, Attila Kotànyi, and Raoul Vaneigem, published in Internationale Situationniste No. 12, September 1969. Our project, considered too violent and provocative, was rejected.

Could you provide some insights into the tracks on the album?

‘Bal pour un rat vivant’

a. ‘Bandiera rossa’

b. ‘Los cuatros generales’

c. ‘Elle était belle. Elle aimait Bach et Chopin. Et les Beatles. Elle était très intelligente, et moi aussi.’

‘Bal pour un Rat Vivant’ is a long musical suite composed of “collages” of various pieces by Komintern, sometimes very short, sometimes longer with violin, bass, saxophone, and guitar solos in the final. Two revolutionary songs are incorporated instrumentally: ‘Bandiera Rossa,’ the most famous of Italian revolutionary songs, and ‘Los Cuatro Generales,’ an anti-fascist song from the Spanish Civil War. It’s a musical piece dedicated to all those who fought for revolution against the dominant ideology, with both a joyful and festive side, but also a dramatic intensity in the progression, ending on a cheerful and optimistic note with the final track, ‘Elle était belle,’ a kind of frenzied jig.

‘Bal pour un Rat Vivant’ symbolizes the new world.

‘Le bal du rat mort’

a. ‘Hommage au maire de Tours’ (Hymn for the Liberation Front of Scatophages)

b. ‘Petite musique pour un blockhaus’

c. ‘Pongistes de tous les pays…’ (From the Anti-Prussian League)

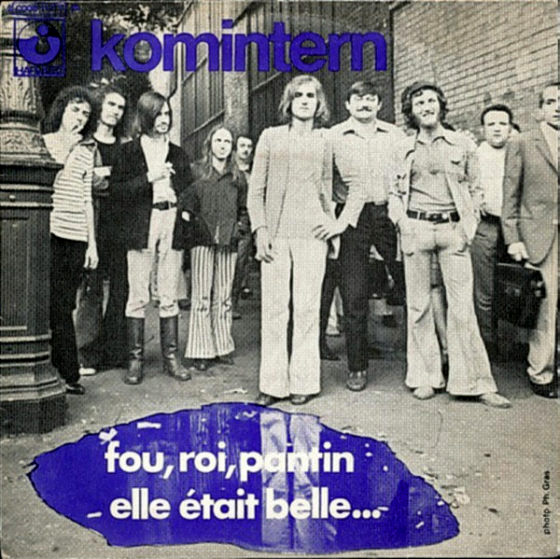

d. ‘Fou, roi, pantin’ followed by: ‘Pour un front de libération des kiosques à musique’

‘Le Bal du Rat Mort’ symbolizes the decadent bourgeoisie, the old world.

The track ‘Hommage au Maire de Tours’ refers to the most reactionary mayor of France at the time. The introduction that Francis Lemonnier and Serge Cattalano wrote, which was censored, was a parody of political discourse.

‘Petite Musique pour un Blockhaus’ was inspired by the free-rock jam we played the day of our first rehearsal. Our rehearsal space produced such a surprising reverb that we called it “the blockhaus,” hence the title of the track. We tried to recreate our very first joint improvisation in the studio.

‘Pongistes de tous les pays’ is based on a patriotic song, part of whose lyrics were distorted or changed to become a revolutionary anti-capitalist anthem.

‘Fou, Roi, Pantin’ has a particular story: One morning, Olivier and I arrived together at the Pathé-Marconi studios and entered through the direct access to the big studio, where equipment was occasionally stored. We saw a beautiful black Les Paul Gibson, so we plugged it into an amp, and Olivier played a series of chords over which I improvised a lead. That’s how the track ‘Fou, Roi, Pantin’ was born, which was later worked on with the rest of the band. Olivier and I were in opinion to make it a vocal track, and Olivier came up with the idea of using a poem by Arthur Rimbaud about the Paris Commune, “L’Orgie Parisienne” or “Paris se repeuple,” from which we only used the refrain. Etienne Roda-Gil helped Olivier develop the final lyrics with his talent for songwriting.

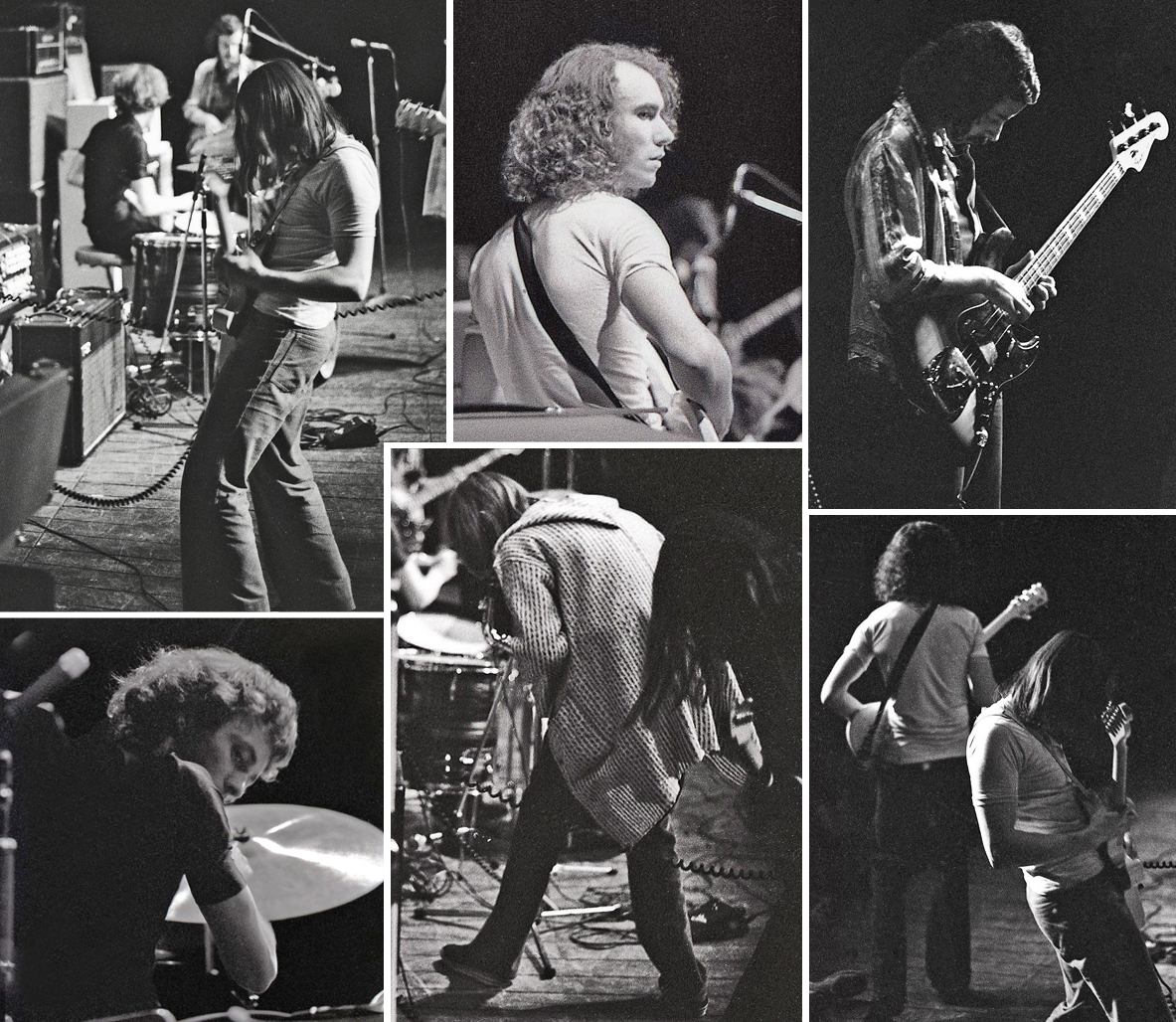

What happened when the album was released? Did you receive much press coverage? Did you perform extensively?

Yes, all the French music press of the time covered it. The album received very positive reception. John Peel even played excerpts from it on his radio show on the BBC and reviewed it in the UK music magazine Disc:

“One of the LPs I bought was by a band called Komintern. They are, I imagine, French. Their LP is released on French Harvest, and it is quite superb. Articulate, witty, played with remarkable skill and precision, and I’d never have heard it if Paul hadn’t told me that it had been the ‘King Kong’ record of the week.”

‘Fou, Roi, Pantin,’ released as a single, was indeed the first French song to be chosen as “record of the week” on the Pop Club show hosted by José Arthur on France Inter, the most musically specialized radio show at the time.

But we couldn’t give many concerts following the release of our album at the end of November 1971, because we were immediately contacted, through Pathé-Marconi, to perform in a musical play, ‘Bella Ciao – La Guerre de Mille Ans,’ written by Fernando Arrabal (French-Spanish writer, playwright and filmmaker living in France) and scheduled to be presented at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris in early 1972. We were the most suitable band to participate, as musicians, actors, and extras, given the content: a critique of the dominant bourgeoisie, militarism, and the complicity of the media. Rehearsals began in early December 1971, and the performances ended in late March 1972. In this play, Komintern’s musical contribution was very limited; we were mainly the performers for composer André Chamoux.

The experience of performing on stage every night was actually quite fun, less demanding than we had feared, but unfortunately, it harmed the cohesion of the band. After ‘Bella Ciao,’ we all needed a break, as everyone’s motivation was starting to weaken. It was at that point that Serge Cattalano decided to leave the band. We had to find a new drummer, and Gilles Yéprémian, with whom I was in contact, introduced us to Gilbert Artman, the drummer and leader of Lard Free, a band he managed. He also offered to manage us. It wasn’t until May 1972 that Komintern was able to start touring again, and it was intensive thanks to the dates Gilles Yéprémian found for us.

What was the craziest gig you ever did?

Our craziest gig took place at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris on March 20, 1971, during a “wild” party organized by its left-wing Action Committee to commemorate the centenary of the Commune of Paris. The concert featured Gong, Komintern, Red Noise, Barney Wilen… Originally, the commemoration was supposed to take place in several locations across Paris, but the authorities banned it. As a result, the École Normale Supérieure remained the only venue open, and a huge crowd gathered there. The night of March 20-21 turned into a completely crazy celebration with a wild atmosphere, especially after the wine cellar was raided… We had never seen so many people in such a state all at once! Pascal Chassin remembers that one particularly drunk student, half-lying on the stage, had his hand resting just under its wah-wah pedal, and it was continuously being crushed without him even noticing! A police intervention took place at dawn, but we had already left before things got completely out of hand. There was a lot of damage, and the school had to close for a while.

And what was the most memorable one?

Our most memorable concert took place in March 1973 in the chapel of the most prestigious high school in Paris: the Lycée Henri IV. We have been transcended by the unique atmosphere of this historically charged venue with its incredible acoustics, and we gave one of our best performances there. For the occasion, I wore a large black cape (matching my black Les Paul Gibson), a nod to the Count Five from ‘Psychotic Reaction’ (posing, on the french EP cover, dressed with large black capes in front of a gothic style house), and the atmosphere made me feel as though I had been transported to ancient times… At that time, guitarist Pascal Chassin, who had become a father, had left Komintern. To give the band a broader rhythmic scope, we decided to add a second drummer to Gilbert Artman, who had a free-style drumming approach. He was joined by Michel Bourzeix, a more rock-oriented drummer. The two of them got along very well musically and brought a powerful sound to the band that, during this concert, completely filled the space.

How long did you stay together as a band, and what led to its dissolution?

Michel Bourzeix stopped in April 1973, closely followed by Richard Aubert, and during this period, Francis Lemonnier no longer participated in all the concerts.

With the departures of Serge Cattalano and Pascal Chassin, founding members of the band, followed by Richard Aubert and Michel Bourzeix, and the absences of Francis Lemonnier, Komintern had gradually emptied himself of its substance. The flame of the band had extinguished, and a sense of weariness had set in; we were no longer motivated. We stopped by mutual agreement toward the end of 1973. Therefore, Komintern existed from May 1970 to the end of 1973, for about three and a half years.

What have you been involved in after the band? Did you remain active in music?

As an underground guitarist in “musical wandering,” I went from the free-pop of Komintern to free-rock with “Les Lapins Bleus des Îles,” a band created by Alain Roux of Maajun, and then to garage-punk. With the punk/new wave surge arriving, I was drawn to its provocative, neo-situationist side, which I saw as a continuation of the Komintern spirit, albeit in a different musical form. I responded to an ad from a young band looking for a guitarist, and we formed “Les Partners,” a band fully focused on energy. Then I moved on to electric rockabilly with the band “Macadam Cowboy.” Alongside all this, I participated in the recording of Pascal’s 45 RPM single, ‘La Nouvelle Européenne’ – Pascal Chassin (Ballon Noir-1979), and Olivier’s album, ‘Photocopies’ – Olivier Kowalski (Virgin-1981). Then, after a few unsuccessful attempts to form a band, I focused on DJing and organizing themed parties, initially with light shows, then with concerts.

“To some extent, the movements initiated by Komintern opened the way for R.I.O. bands.”

Do you feel that Komintern paved the way for upcoming Rock In Opposition bands?

To some extent, the movements initiated by Komintern opened the way for R.I.O. bands. One can indeed establish a lineage, or at least an analogy, between the F.L.I.P. (Force de Libération et d’Intervention Pop) created by Maajun and Komintern in 1970, then the Front de Libération de la Rock-Music created at the initiative of Komintern and Gilles Yéprémian in 1972, and the Rock In Opposition movement created in 1978 at the instigation of drummer Chris Cutler from the band Henry Cow, even though its scope of demands was much more limited. In the meantime, there was also the collective Dupon et ses Fantômes, formed in 1976 by Camizole, Etron Fou Leloublan (which would become part of the R.I.O. bands), and other French groups who, through their music and libertarian attitude, continued the spirit of Komintern, Maajun or Barricade before the creation of the R.I.O. movement.

What currently occupies your life?

I play guitar for myself, without being part of a band.

I listen to a lot of music, both records from the ’60s to the ’90s and from the 2000s, if they align with my musical tastes.

On the occasion of the release of La Pop Sauvage, which I spent many months writing, I made contact or reconnected with many people interested in the subject of French musical underground. I have stayed in touch with some of them, and we regularly correspond.

I also read a lot.

Last word is yours.

Given the catastrophic situation of our planet (wars, climate change, the rise of religious or other extremists), while the “spectacular merchant society” continues to pollute and dominate, I observe, stunned but not resigned, that “Vivre la Mort du Vieux Monde” (*) (“Live the Death of The Old World”) is still relevant.

(*) Title of the only album by Maajun (Vogue/Pop Music-1971) reissued by Souffle Continu label in 2022.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Komintern’s first concert on May 26, 1970: Michel Muzac, Pascal Chassin, Olivier Zdrzalik, Serge Cattalano, Francis Lemonnier (photos by Marc Lamotte).

where can i buy this book ?