Wendell Harrison | Interview | “We are all concerned with our environment, including social, economic, political, and artistic aspects”

Wendell Harrison’s path in jazz is a vivid reflection of the music’s power to evolve, inspire, and connect. From his early years learning clarinet and piano to his eventual mastery of the tenor saxophone, Harrison’s growth as a musician is marked by his deep immersion in the sounds and soul of Detroit.

The city’s rich blend of bebop, blues, and Motown shaped him into a musician with both technical mastery and expressive depth. He recalls playing in local clubs, developing his sound alongside future jazz greats like Charles McPherson, Roy Brooks, and Lonnie Hillyard.

Mentored by Barry Harris, Harrison refined his improvisational voice, learning that jazz is not just about notes but about conversations, community, and shared passion. His embrace of John Coltrane’s groundbreaking tenor sound in the late ’50s was pivotal in his evolution, as it opened new doors to bold improvisation and a freer expression of jazz. Harrison’s distinctive approach to the saxophone is rooted in both the tradition of bebop and the radical shifts of the ’60s, with influences ranging from the fiery solos of Sonny Rollins to the spiritual depth of Coltrane’s sound.

Harrison’s latest release, ‘Tribe 2000,’ a collaboration with fellow jazz legend Phil Ranelin, further solidifies his place in the music’s ongoing conversation. Released via ORG Music, the album offers a bold mix of reflection and innovation. Tracks like ’13th and Senate’ capture Harrison’s connection to his Detroit roots, while ‘He Is The One We All Knew’ echoes his personal experiences and relationships from the past.

As Harrison prepares for his upcoming performance at Ann Arbor’s Blue Llama and looks forward to touring Europe, Japan, and Australia, his reflections on his life in jazz are a testament to the ongoing vitality of the art form. From playing alongside Marvin Gaye and Sun Ra in his early days to recording with today’s innovators, Harrison’s story is intertwined with the very pulse of jazz—always evolving, always alive.

“We are all concerned with our environment, including social, economic, political, and artistic aspects”

Can you share how the spirit of Tribe Records has evolved from its inception in the early ’70s to this recent release? What do you think unites the members of the Tribe across generations, and how does that bond manifest in your music?

Wendell Harrison: Tribe Records was, and still is, a cadre of jazz musicians who became band leaders, producers, and publishers. These musicians are highly skilled and possess an abundance of experience and knowledge, having performed all over the world.

In 1970, in Detroit, Michigan, the core of Tribe artists came together to produce their individual album releases. Pianist Harold McKinney, trumpeter Marcus Belgrave, trombonist Phil Ranelin, drummer Doug Hammond, and I sat down and had a discussion about recording and releasing our music independently under Tribe Records. As musicians, we had been glorified as great sidemen who garnered respect from radio stations and music publications worldwide.

I had started recording for Atlantic Records while living in New York. However, the project was not completed, and it was shelved. I was being produced by Hank Crawford and Tom Dowd, who were supporting me, but all of a sudden, I got dropped. The same thing happened to Marcus Belgrave, Phil Ranelin, and Doug Hammond, which was not uncommon for many great artists. Oftentimes, if an artist does not have someone advocating for them—such as a manager or a good producer to keep the record company focused—the project might be delayed or dropped. So, we made our dreams manifest by working together.

As you prepare for the release of ‘Tribe 2000’ archive recordings, what aspirations do you have for this project? Are you excited about the ORG double vinyl release?

I plan to do interviews for magazines, radio, and social media to spread the word about ‘Tribe 2000.’ All our releases have been very well received. Yes, I am excited about the ORG double vinyl release because it represents our music in a classical jazz setting and continues to support our legacy as Tribe. This is another historic endeavor, highlighting performance quality audio and packaging.

Your longstanding partnership with Phil Ranelin is special.

Phil Ranelin and I have been working together for over fifty years. He has performed with Tribe as well as with various international ensembles over the years. Phil is a prolific songwriter and trombonist who has attracted interest from jazz fans and connoisseurs of the art form. My contribution to this relationship is my improvisation as well as my compositions.

We are committed to writing music that reflects the environment, climate change, politics, and social events, which makes us relevant. We are jazz messengers for music fans worldwide—writing compositions for the people while maintaining our integrity as jazz musicians.

‘Tribe 2000’ is the original music of Phil Ranelin, featuring Tribe members pianist Harold McKinney, trumpet player Marcus Belgrave, John Arnold on guitar, bassist Ralph Armstrong, pianist Pamela Wise, and me on tenor saxophone. Performing these compositions by Phil, I try to solo based on melody and rhythm, avoiding a focus on technique or playing too many notes that lack meaning or relevance to the song.

“Tribe 2000, is a retrospective view of the good times in the ’60s through the lens of Phil Ranelin.”

How did this political aspect influence the music you created and the projects you undertook with Tribe?

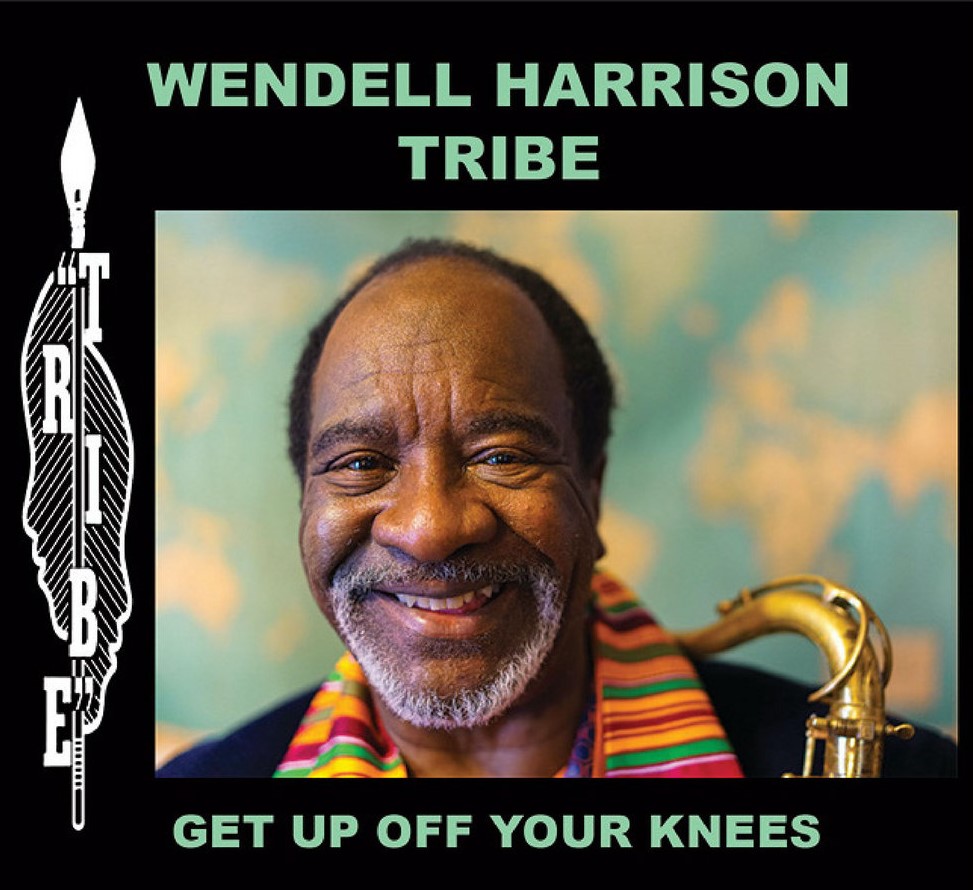

We are all concerned with our environment, including social, economic, political, and artistic aspects. My last album release, ‘Get Up Off Your Knees,’ has many political reflections, highlighting attitudes about education, self-determination, and romance from West Africa. The album features songs like ‘Educator,’ ‘Get Up Off Your Knees,’ and ‘Revolution,’ to name just a few, which carry political and social messages performed by various indigenous jazz artists.

‘Tribe 2000’ reflects Phil Ranelin’s life, particularly his relationships with trumpet player Freddie Hubbard (‘Freddie Groove’) and saxophonist Eddie Harris (‘Cold Duck’). Phil’s song ’13th and Senate’ is a reminiscence of growing up in his hometown, Indianapolis, IN, and hanging out on Senate and 13th Street, socializing, playing in local clubs, and getting high. The version of ‘He Is The One We All Knew’ was written for a girlfriend he stayed with before departing for Detroit, MI, in 1967. This release, ‘Tribe 2000,’ is a retrospective view of the good times in the ’60s through the lens of Phil Ranelin.

Can you share any memorable moments from the recording sessions that illustrate the collaborative energy?

Pianist Harold McKinney brought great emotion and sophistication to Phil’s compositions. Playing with Harold always brings out our best qualities as jazz improvisers, challenging us to keep reaching for excellence. He has passed on and has become our ancestor. Harold McKinney’s contributions as a pianist, composer, and educator will forever be missed. This project exemplifies his grace and passion.

Another jazz master on this recording who has passed on is trumpet player Marcus Belgrave, who has also become our ancestor. Marcus and I have performed and taught in various ensembles worldwide. I consider him a great interpreter and improviser, adept in jazz, Latin, and R&B, with an abundance of experience. When Harold, Marcus, and Phil recorded or performed together, magic happened. This project, ‘Tribe 2000,’ exemplifies that magic.

Wendell, growing up in Detroit, you were immersed in a rich tapestry of musical influences. How did the gritty, soulful atmosphere of Detroit, with its blend of jazz, blues, and Motown, shape your early musical identity?

I grew up in Detroit in the ’40s and ’50s, learning to play bebop jazz with many young players. I started in high school, learning Charlie Parker’s and Dizzy Gillespie’s compositions, as well as popular show tunes written by Cole Porter, Ira Gershwin, Duke Ellington, and many more.

There were several young jazz ensembles at Northwestern High School, where I attended. As I learned the standards and jazz compositions, I began performing with student musicians. Young guys like alto saxophonist Charles McPherson, trumpet player Lonnie Hillyard, pianist Harry Whitaker, bassist James Jamerson, and drummer Roy Brooks helped me develop a jazz bebop concept.

Furthermore, Lonnie Hillyard introduced me to the great Barry Harris, who was world-renowned as a prolific bebop jazz pianist and educator. His jazz education influenced all of us as young jazz musicians growing up in Detroit. He would teach and perform locally while also going to New York to record for major labels. Eventually, Barry introduced Charles and Lonnie to Riverside Records in New York, and he also used Roy Brooks on several recording sessions. Barry served as a launching pad for guys who went on to perform with major jazz artists, including Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, and many more.

Bassist James Jamerson started by playing bebop, emulating jazz bassist Ray Brown, but he became an innovator and producer for the renowned Motown Records, recording for Marvin Gaye, the Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, and other Motown artists.

I played with local groups, performing at weddings, birthday parties, and proms while still in high school. Before relocating to New York, I performed with Marvin Gaye and the Choker Campbell Big Band and played in local clubs and theaters. I left Detroit for New York at the age of 19. My performances expanded in New York, where I got a chance to play with artists such as Big Maybelle, the Lloyd Price Big Band, Dionne Warwick, Chuck Jackson, Sun Ra, Grant Green, Hank Crawford, and many more. When I wasn’t on the road or recording with these artists, I was working with my own ensembles.

Ironically, my Detroit experience and preparedness were invaluable in advancing my career in New York and beyond.

You started with the clarinet at a young age before transitioning to the tenor saxophone. What prompted this shift, and how did it affect your musical expression? Did you find that each instrument opened different creative avenues for you, particularly in your approach to improvisation and melody?

After learning to play the piano at the age of five, my grandfather purchased a silver metal clarinet for me when I was eight years old. My mother took me to a private piano teacher, who also began teaching me basic instruction on the clarinet. The teacher’s name was Mr. Hewitt, who taught music in the neighborhood and lived a few blocks from my parents’ home. As I recall, he was the one who sold the clarinet to my grandfather.

I wanted to play in the elementary school band, which was a prerequisite for taking private lessons outside of school. After a few lessons, I was accepted into the band at Thirkell Elementary School. There, I performed and learned to read music with the band, playing marches and classic popular band charts. I continued playing through the 4th to the 10th grade.

However, when I started high school at Northwestern, I was introduced to jazz and acquired an alto saxophone. I was inspired and enthused about learning to play jazz. Older jazz students and musicians outside the school helped nurture my development by giving me certain tunes to learn and guiding my solos. Pianist Barry Harris taught me the methodology of approaching improvisation, which was extremely helpful at the age of fifteen. His lessons, along with the guidance of older musicians, gave me the skills to attract employment with local bands around Detroit and Cleveland, Ohio.

At sixteen, I began playing the tenor saxophone. Sonny Rollins was a popular tenor saxophonist in the ’50s with many major record releases, and Barry Harris encouraged me to listen to him. I did, and I began to attract interest from bandleaders. I emulated Sonny’s big tenor sound, which allowed me to work jazz gigs with both small groups and big bands. By 1956, I was reading music and improvising, which led to abundant work opportunities.

However, the tenor saxophone sound changed when Miles Davis released recordings with his new band in the late ’50s. Miles introduced John Coltrane in 1957, with recordings such as Round Midnight, Fast Track in 1958, Milestones, and 1959’s Kind of Blue. John Coltrane’s new tenor sound rejuvenated Miles’ career, and all the young saxophone players started listening to Trane. This was the new wave, and I was baptized into the new sound for the tenor saxophone.

What does the rest of your year look like, and is there anything else you would like to share with the readers?

This year is beginning to wind down. On November 15th, I’ll be performing with my band, Tribe, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, at the jazz club The Blue Llama. I’ll also be teaching a jazz studies class for the Detroit Jazz Foundation in Detroit twice a week.

Next year, I plan to organize a tour that includes Europe, Japan, and Australia, as well as release more jazz recordings.

Klemen Breznikar

Interview conducted on October 18, 2024. Special thanks to Andrew Rossiter for making this possible.

Wendell Harrison Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube

Org Music Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp / YouTube