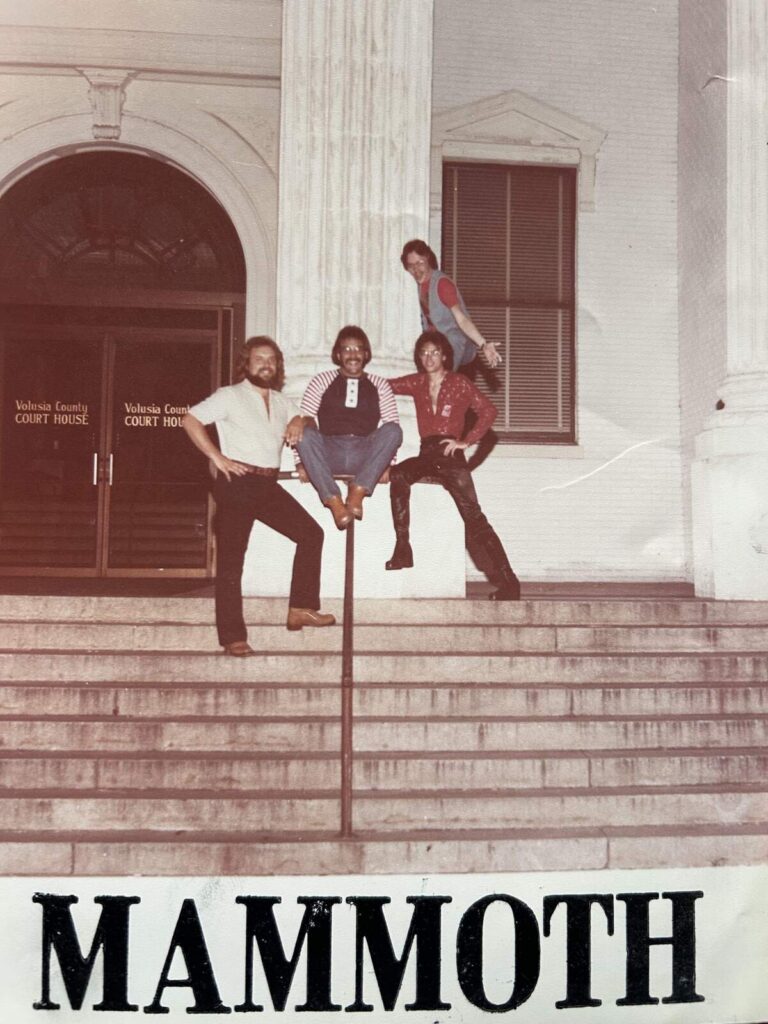

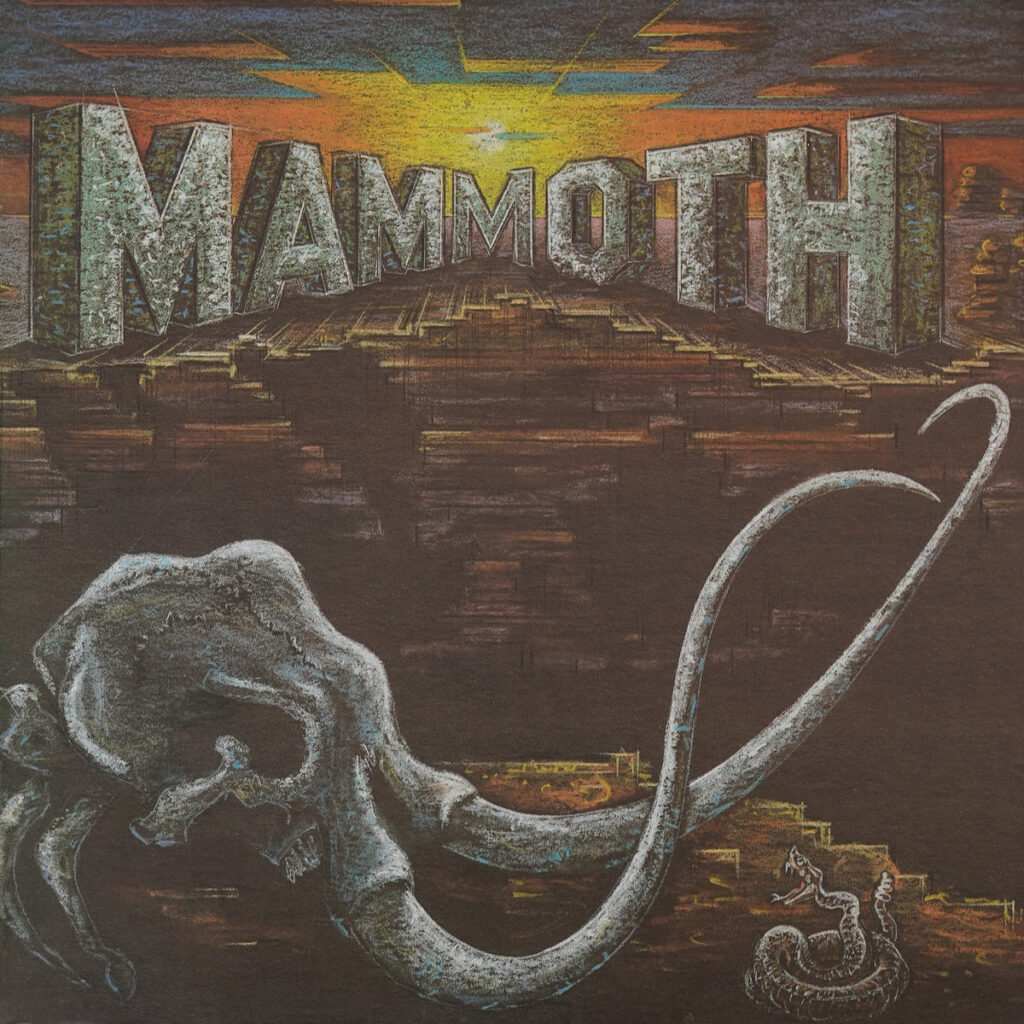

Mammoth | The Lost Southern Rock Gem Reborn

Mammoth could easily be mistaken for well-known southern rock legends, walking a fine line between classic rock ‘n’ roll grit and thoughtful composition.

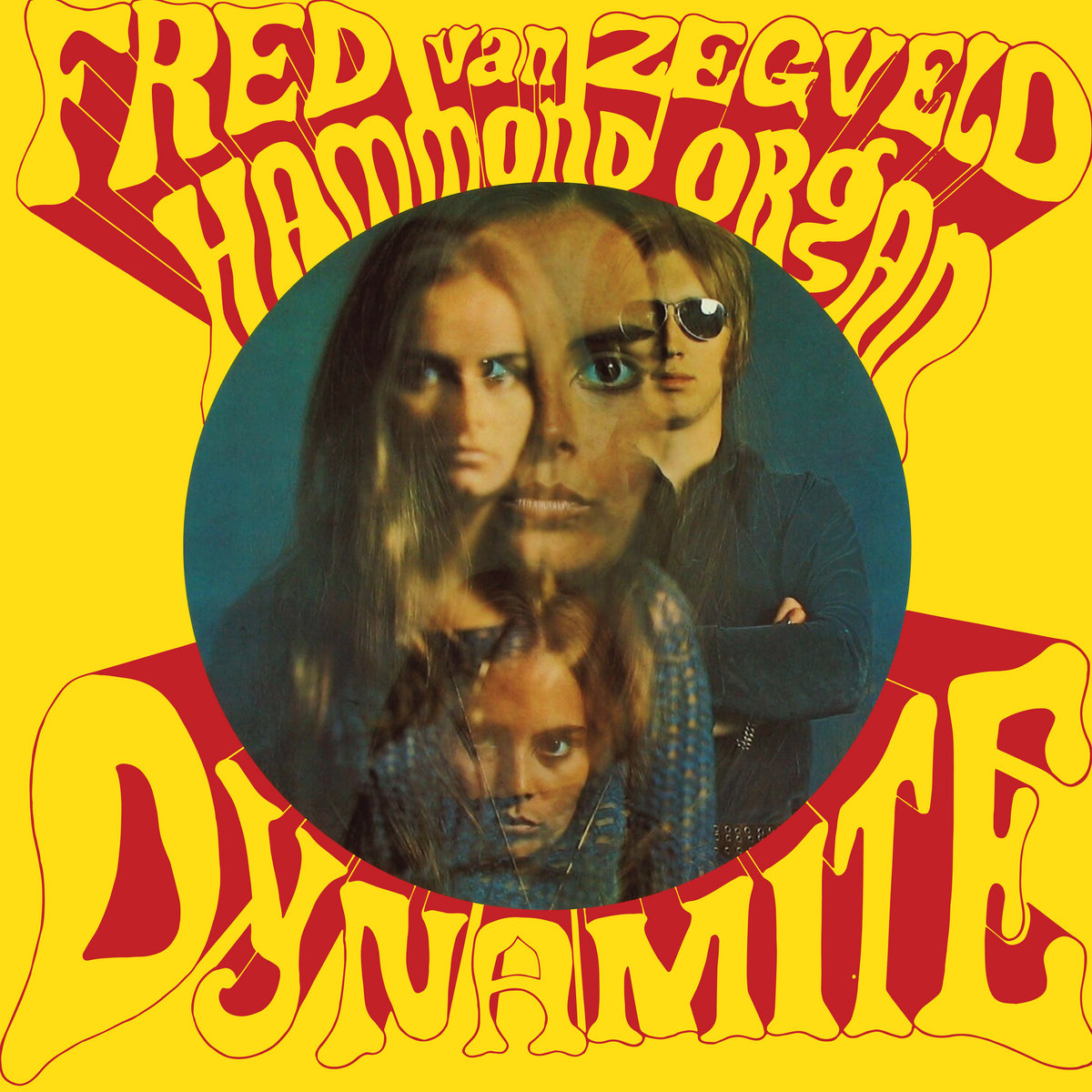

Their dual guitar assault, laid-back vocals, and rock-solid rhythm section give every track a distinct vibe, making you quickly realize you’re listening to a long-lost gem from the analog days. Although it may sound familiar, there’s a slim chance you’ve heard this rare treasure before—it was originally released in 1981 and has remained scarce ever since. Now reissued by RidingEasy Records, this sole album was recorded at Relayer Studios. Citing the words of Paul Major: “Mammoth is a grabber right out of the gate; every step they take is unleashed with deadly economical precision. They may flash on Lynyrd Skynyrd and other vintage southern rock traditions, but the brilliant way the vocals are recorded and the to-the-point interlocking guitar moves will fire up anyone into any sort of hard rock.”

“We were different”

Lance Barresi: You all live in DeLand? Did I pronounce that correctly, by the way? Is it DeLand or Deland? Or how do you pronounce that?

Ron Herman: DeLand. Just like the plane, but it’s DeLand—D-E-L-A-N-D.

Got it. So, were all the band members from that area?

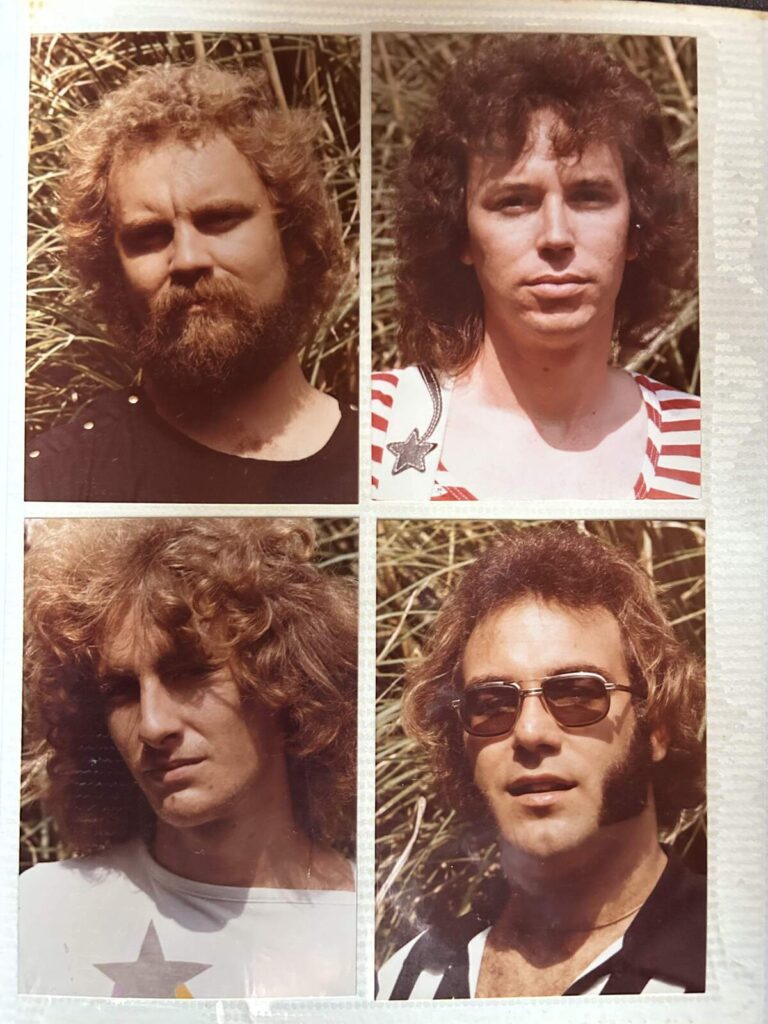

No. Bill Abell was from Kentucky, Joey Costa and I are from Ohio, and Buzz Fetters was from Florida.

How did you all end up down there together?

Well, it’s crazy. Everybody was in the construction business in one way or another. Bill was in the carpet business, I owned a lumber yard, and Joey was a really good customer of both of ours. We kind of just kicked around, and one time we all went to lunch, and, well, we just put it together. Buzz was a good friend of Bill’s. I don’t even know how that connection happened, but he was a great guitar player. He joined the lunch crew later on, and we hit it off.

Pretty Cinderella-like—a truly working-class band.

Well said. Yeah, that’s exactly how I’d describe it.

Cool. What was life like in DeLand?

DeLand is very laid-back. It’s the home of Stetson University, first of all. Back then, it was a Baptist convention-sponsored school. They only allowed men on the second floor of the campus buildings. We played a lot there.

The town as a whole is just like a bedroom community outside Orlando. Being 40 miles north of Orlando, that’s where all the action really was. DeLand hasn’t changed much since then. But back then, there were just two places where a band could play: The American Room and a place literally called The Other Place. We played them both. It wasn’t a large town at all.

And when you say The Other Place, you mean the venue was actually called The Other Place?

Odd as it sounds, yes. The Other Place. What a name, huh? Everyone referred to it like that because the American Room was a huge venue on the bottom floor of a massive hotel. So, “The Other Place” just became its name.

And when you all got together, you were already playing your respective instruments, I assume, in other bands?

Oh, yeah. Joey had played with an Alice Cooper tribute band. Our second guitar player, Adolph Ziegler, was with Black Oak Arkansas—he’s on the second album, by the way. I had been playing since I was 13. I’m not sure how far back Bill went, but he had the voice. So, yeah, we were all seasoned musicians by that point.

It shows on this album. And before I forget, the second album—it was never released, right?

That’s correct. There’s a story there, mostly financial issues, but I still have it. It’s on a half-inch four-track tape.

And that technology is long gone.

Of course. But I finally found a machine at a yard sale and got it repaired. Now I’m at the point where I can start working on the tracks again. Otherwise, I wouldn’t even be able to play it.

Wow. We’re waiting with bated breath to hear that unreleased second album.

It’s coming. Adolph was a wild man on the guitar, so it’s going to be good. I’ll get to it.

Fantastic. Are there any other bands you all played in before or after Mammoth that you’d like to mention?

I don’t know much about Joey’s background, but I played with a very well-known band up in Northeast Ohio for about five years called The Sound Investment.

Oh, wow.

Yeah. Back then, the disco and show scene was big. We were a seven-piece band with horns. We had seven tuxedos, and whenever we went out to play, we did well financially—but we also had to pay the cleaners! It was a crazy scene in Cleveland in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Oh, of course. As you can imagine. Absolutely. You gotta spend money to make money.

And we did well.

Awesome. So, how did you all get into rock and roll in the first place? If you can’t speak for the others, maybe just your own story?

Well, my story starts with my dear old dad. He played a 1952 Gibson L-3 guitar. He’d perform at county fairs, Grange events, and church gatherings. Back then, it was mostly Elvis Presley-type stuff, and it really intrigued me. I had three years of piano lessons, but I’d never played drums until later. Something about it just struck me, though, and I picked it up.

It was kind of a Cinderella story in a way—it just happened. I tried my hand at the old Elvis and Johnny Cash stuff, and it was fun. But yeah, my interest came from my father. He was into all that Sun Records rockabilly stuff, which goes way back.

So that was his style back then?

Yep, exactly.

Cool. You touched on this earlier, but do you want to elaborate on how the members of Mammoth originally met and what led to the band’s formation?

Well, Bill used to come into my lumberyard for glue and supplies, and Joey would drop in for materials too. We’d have normal conversations, just a bit of fellowship. One day, we decided to call everyone together for lunch. We sat down, talked about it, and decided to give it a go.

It was really better than any of us expected. It started out as acquaintances getting together, but we struck a lucky stream. That lunch turned out to be momentous.

What a pivotal lunch that was!

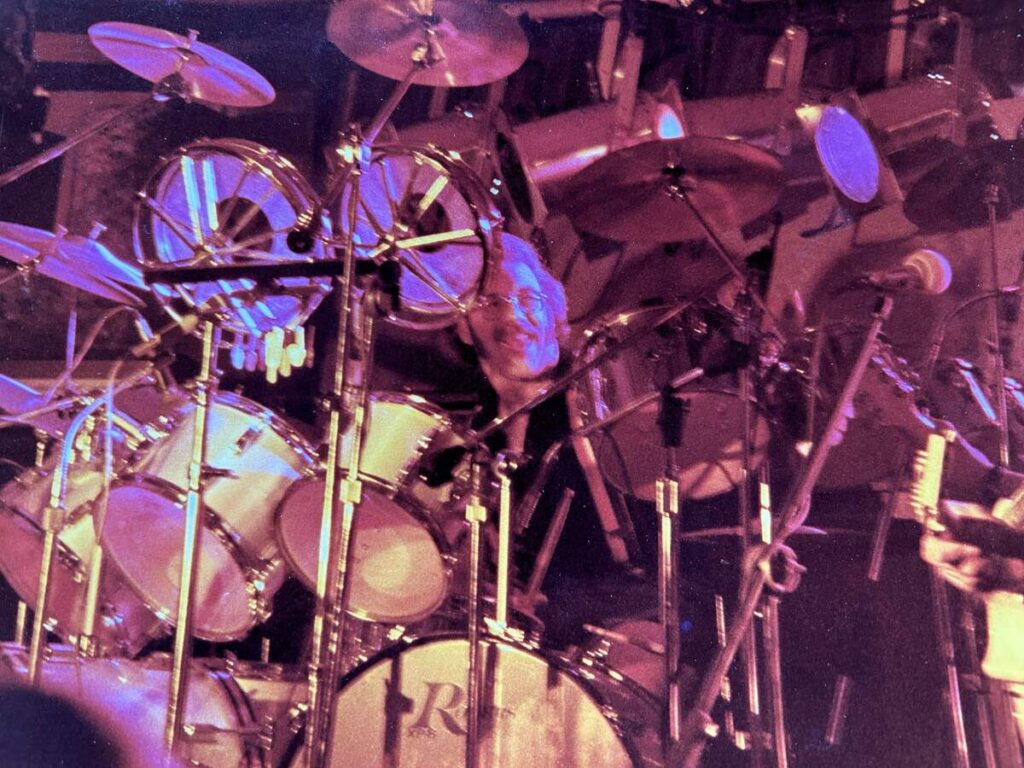

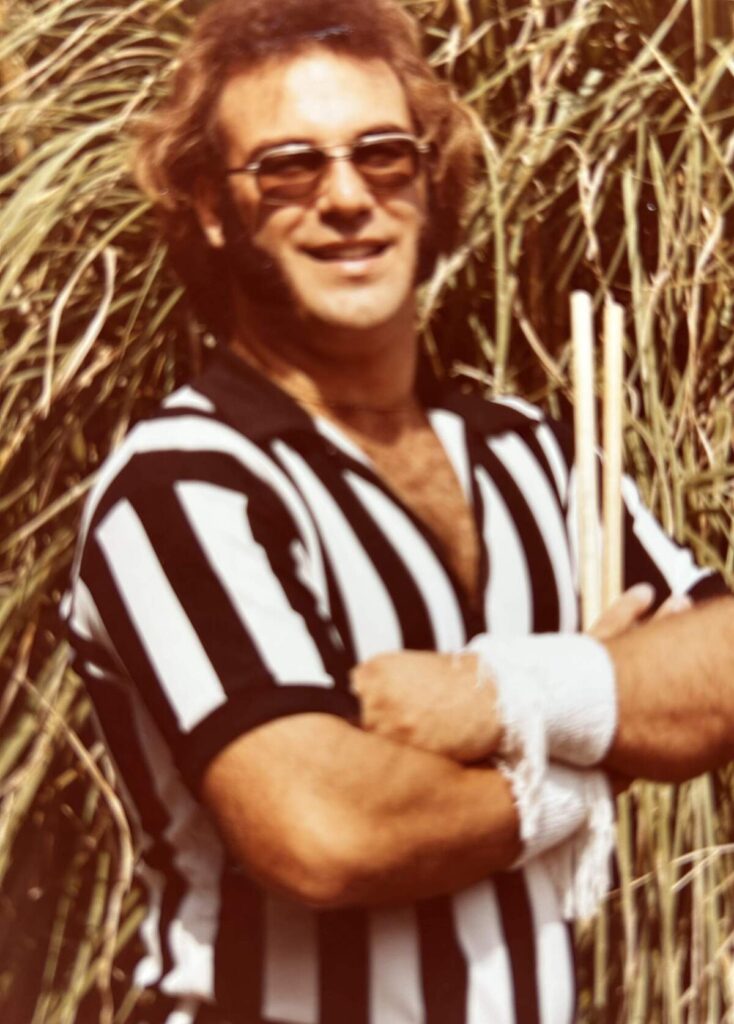

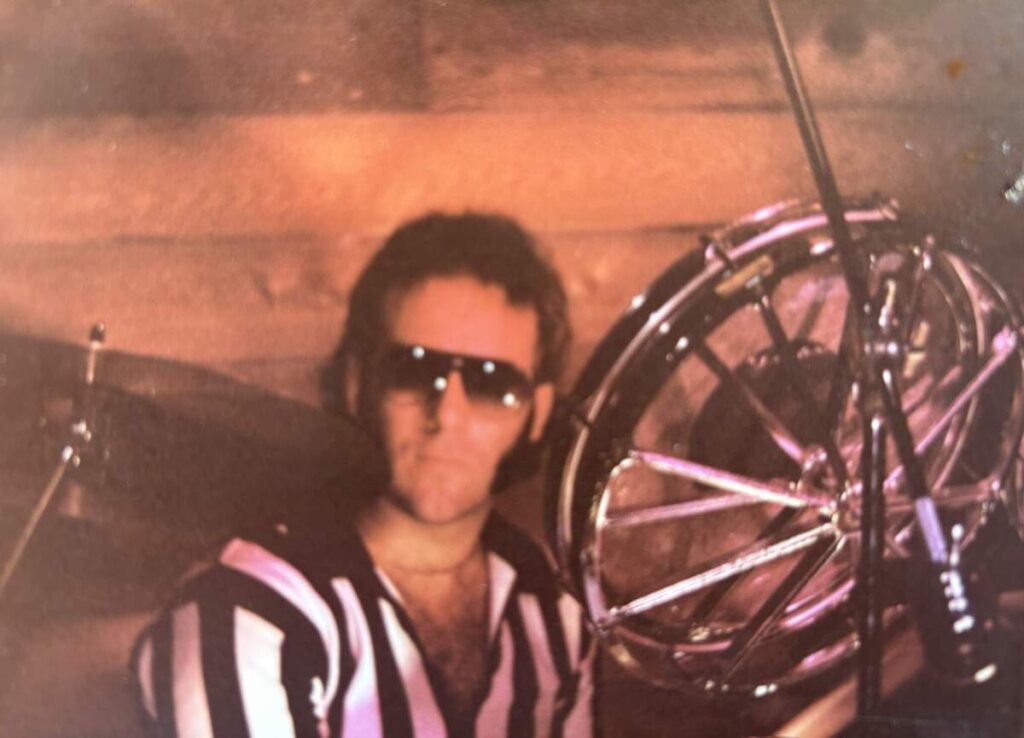

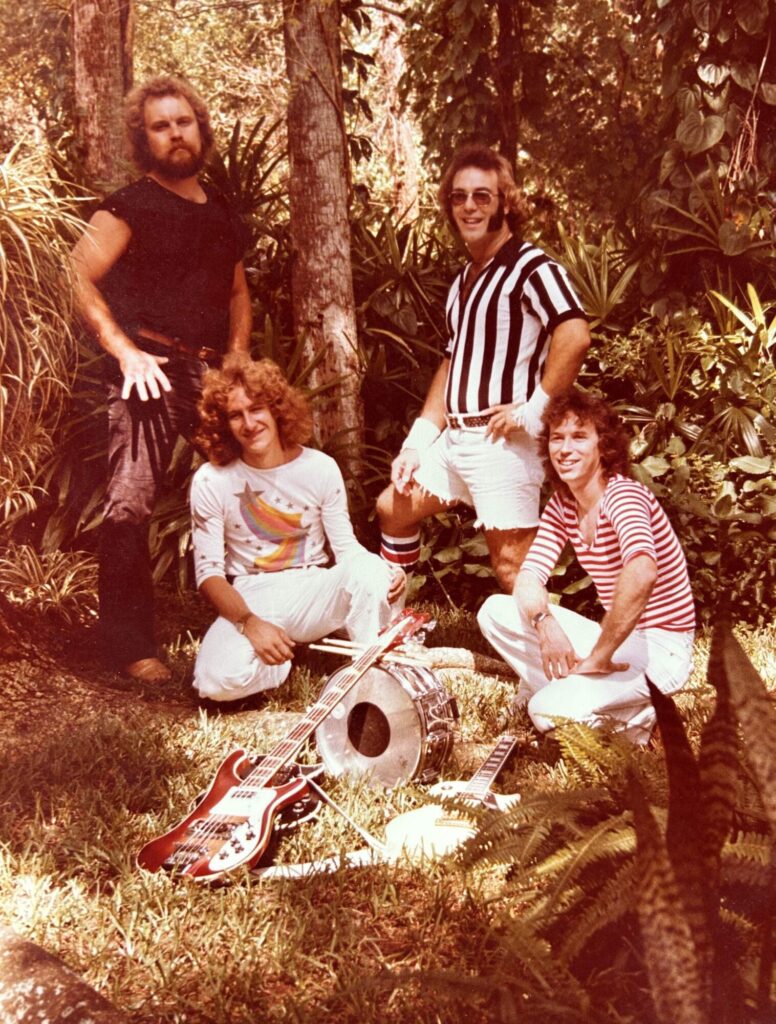

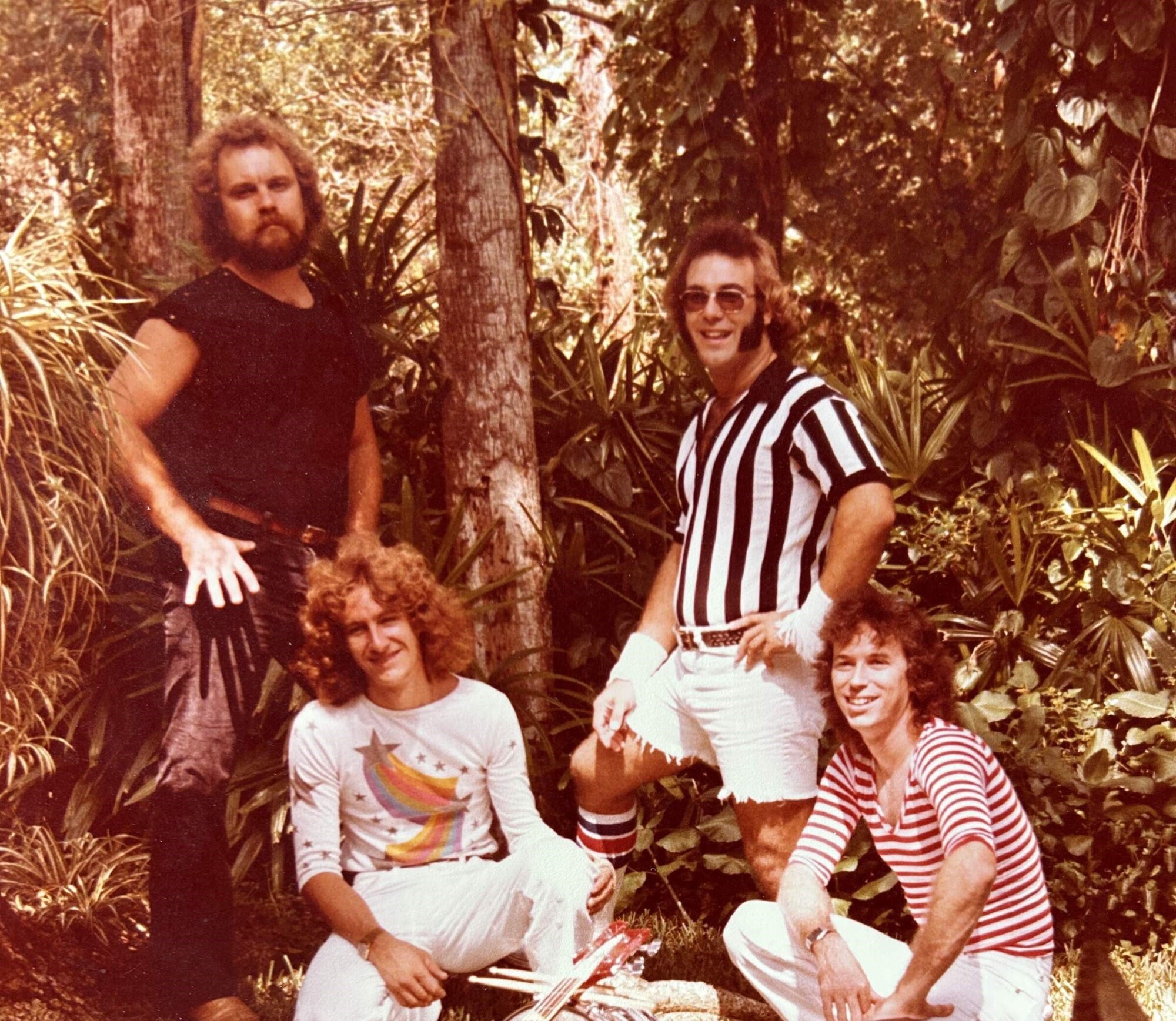

Definitely. I remember us sitting around a table having beers, trying to come up with a name for the band. We wanted to put on a big show. I had a massive double-bass Rogers drum set with 29 cymbals, Joey had a double Sunn bass setup, and both guitarists had double-stacked Marshalls.

Even though we’d only plug in one cabinet at some of the venues, we still brought a huge sound system with us—a big Sunn system. That’s where the name Mammoth came from.

We did a bit of research before franchising the name back in, I think, ’70. Van Halen had just dropped the name, so we picked it up for use in the U.S. only. The idea came from that conversation around the table—beers, big sound, big show, and a lot of ambition. And it worked! We had fog machines, flash pots, all of it.

Sounds incredible. Is there any video footage of you all from back in the day?

There is! A production company followed us around at one point because I bought a bunch of gear from this guy. I’ve got it all on VHS tapes.

The footage includes concerts with the fog machines and flash pots—just amazing stuff. I’ve been meaning to get it converted. I finally found a VHS player at a yard sale and got it repaired, so I’m working on getting everything digitized now.

That’s fantastic. I’d love to see that someday.

I’ll make sure you get a copy.

Let’s go back to DeLand for a minute. You mentioned the two main venues there—the American Room and The Other Place. What was the scene like? Did you play with any notable bands?

DeLand was, and still is, a sleepy little town. The American Room and The Other Place were the main spots for live music. But once we got going, our agent had us on the Big Daddy’s circuit. We played everywhere—from Savannah to West Palm Beach, hitting colleges like Gainesville and other spots that loved our big show style.

Locally, there wasn’t much. DeLand was quiet. But we did play in Daytona once with Terry “Hulk” Hogan, back before he was the Hulk Hogan. He played bass in a band back then. That was at a club called The Hole. It was a fun experience—he was just a big beach bum at the time.

That’s wild!

It really was. Local bands? There was one called Fantasia—they were great. Jerry Hendy from that band is still around, actually.

Sounds like a scene full of colorful characters and unforgettable moments.

He was the lead guitar player in a band called Stranger. Stranger actually made it. They weren’t quite funded properly, but they were out there as well.

Did you play with Fantasia and Stranger in the same area?

Yeah, we did. Mammoth played original stuff. We really didn’t do much in terms of covers, other than maybe ‘Freebird’ and some other classics. When we put Mammoth together, we focused on writing our own music. We even put on our own concerts, like when we played at the American Room. It was a Mammoth show from start to finish.

We were different, and maybe that made us less popular since we didn’t do covers, but that’s what we wanted to do. And we did it well.

That’s amazing. I really appreciate that because I find an original album from 1981—or any other time in the past—far more interesting than a collection of covers.

Yeah, exactly. Wait until you hear the second one. I can’t wait to get your response. We were just getting going, but finding good guitar players and keeping everyone on track was tough. That was probably our downfall—trying to find reputable and committed personnel. Still, we wrote some good stuff.

You sure did. Beyond that, did the band have an overall vision? Were you aiming for anything in particular in terms of sound or ambition?

Our main goal was to make music and have a good time. There was a place in Orlando called the Navy Base—a huge venue. The recruits would have their time off, and sometimes there’d be 2,000 or 3,000 people in the room. They didn’t realize we were nobodies, but we presented ourselves like we were one of the biggest bands around.

That energy charged us up. We’d go out, put on a big show with a light show and a huge sound system. We looked good and aimed to be as entertaining as possible. That punch-you-in-the-face vibe was what kept us going. It was all about making people happy.

Nothing wrong with that! How many copies of the LP did you press back in the day?

When we first started, we didn’t have much money. The first pressing was 288 copies—two gross.

288 copies. That’s crazy!

After those sold, we followed up with another 800 about three or four months later. That’s as far as it went. We had some support from WDIZ, one of the biggest radio stations in Central Florida. Bob Church, the manager, got us about four months of airplay. But they’d put us in the after-midnight slots, not the prime ones.

Most of our budget went to promotion and production, but without a big push, it’s hard to get anywhere. Still, I’m proud of what we did. It was a good run.

Is there any way to tell the difference between the first pressing of 288 and the second pressing of 800?

Nope, they look exactly the same.

I’ve been asked this by a couple of collectors because I think Discogs has you listed incorrectly alongside another band with the same name. There’s a single from 1978 called ‘If You’re Wondering’ on Saturn Records by a band called Mammoth. Can you confirm that wasn’t your band?

Absolutely correct—that wasn’t us.

Glad we cleared that up. So, you were getting some airplay and self-releasing the album. Did you ever get interest from bigger labels? Were you actively pursuing that?

Honestly, it came down to finances. Even though I owned a lumberyard and a carpet business, funds were tight. We took it as far as we could financially. That’s why it didn’t go further.

We would’ve loved to have had conversations with a big label, but it never got to that point.

No A&R guys sniffing around at your shows?

If they did, we didn’t know about it.

That’s surprising, especially considering how close you all were to Jacksonville, which is essentially the mecca of the Southern rock sound.

Yeah, but Stranger—another band I mentioned earlier—had more money behind them and got most of the attention. We were a similar band, but they had a leg up. I think their drummer’s mother even mortgaged her house to get them a paid record contract. We weren’t going to go that route.

It was competitive, and competition in this business can be tough.

Nothing wrong with a little friendly competition—though it’s not always friendly. Did you have a mission for Mammoth’s sound when you started, or was it just the natural result of the four of you coming together?

It was more of a natural result. We wanted to make people happy, and we played to our strengths. Everything just kind of came together in the rehearsal space.

That’s exactly what I’d call that—a natural sound.

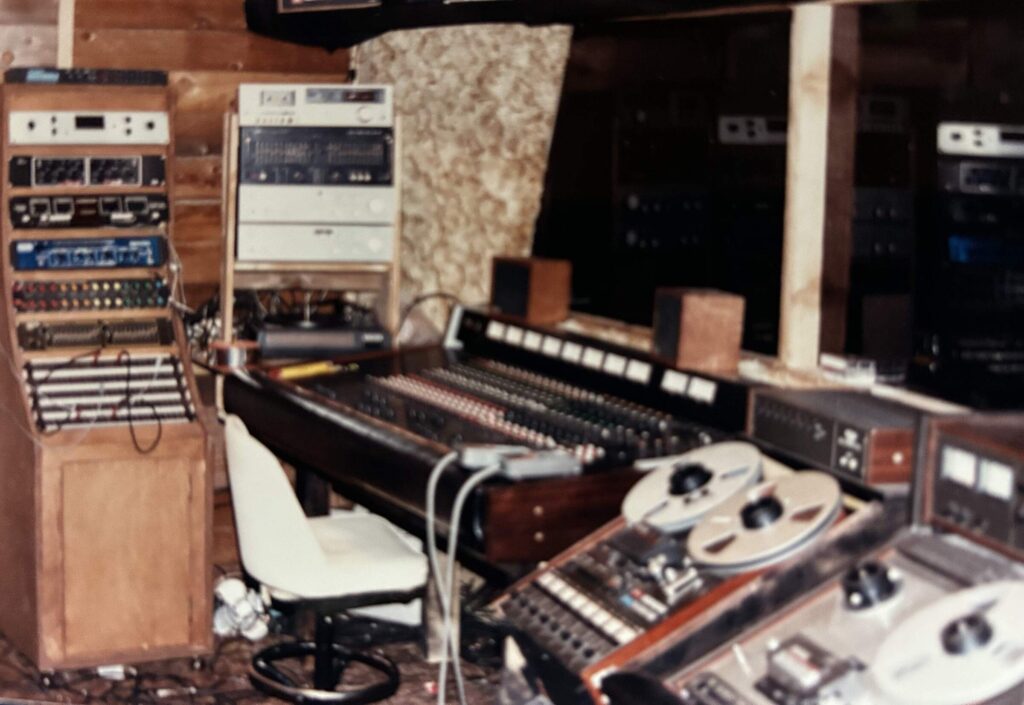

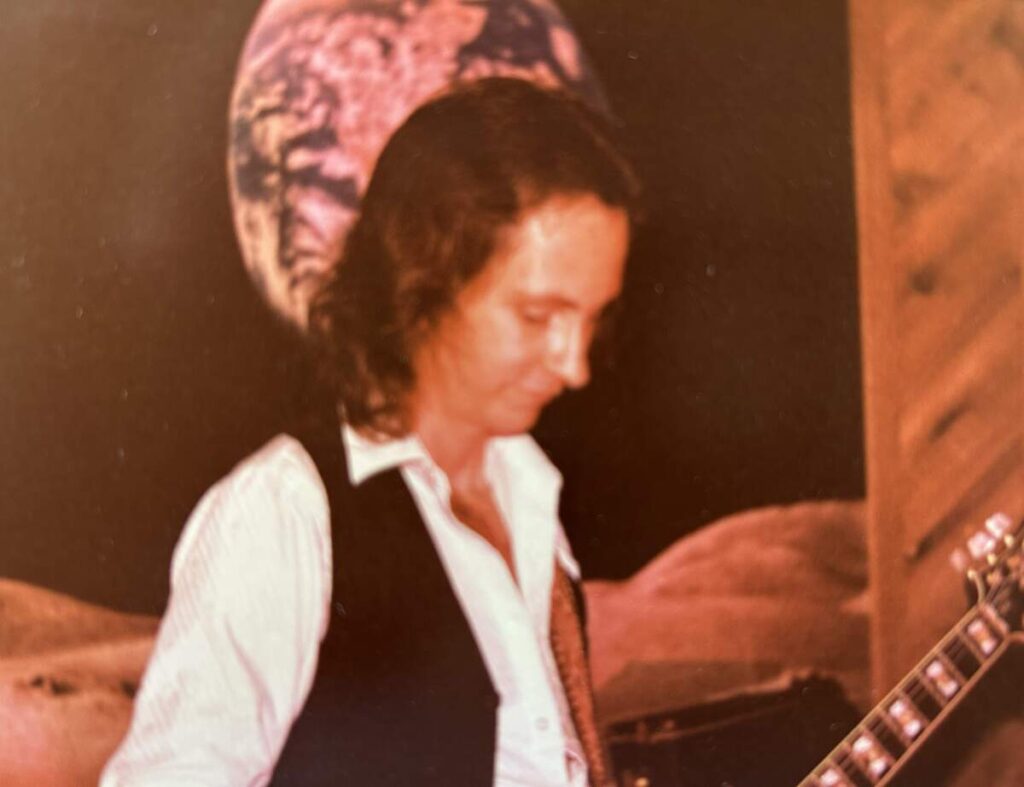

We didn’t rely on a lot of pedals or sound emulation. We were just four talented guys making it work with what we had, and it came out pretty good. That’s about enough said. Sure, we did a few things in the studio—compression, harmonizing—but when we played live, it was straight-up raw. Maybe we’d use a fuzz box or a basic digital effect. Back then, we had tape delays, you know, the old machines. But yeah, this was 1979, 1980, 1981—45 years ago now.

Speaking of the sounds on the record, can you elaborate on the synthesizer sound featured pretty prominently on a few tracks?

That was an Eventide Harmonizer, a fantastic piece of equipment for its time. We used it to overlay and dub those parts. It’s what gave us that tone, which, in some cases, sounds like a synthesizer—but it wasn’t.

What kind of equipment is that? Was it a pedal you ran the guitar through?

No, it wasn’t a pedal. It was a rack-mounted unit made by Eventide. This thing could do crazy stuff—like make your voice sound like Donald Duck or Mickey Mouse. But when you ran a guitar through it, it gave you a sound like Tom Scholz in Boston—that sustain, that diversity. We used it in the studio to add that sustain and synth-like quality to the guitar sound.

Wow, okay. So, just to clarify, that laser-like sound on the record—was that from the Eventide as well?

Yeah, exactly. I also had a set of digital pads I used for effects, like bullet shots and explosions.

Really? Do you remember what kind of digital pads those were?

I can’t think of the name now. They were so hot back then you probably can’t even find them anymore. But we used them on tracks like ‘Outlaw ‘to add that extra bit of character.

That’s amazing. It definitely adds a unique flavor to the record. There aren’t many southern rock albums with that pronounced of an effect.

I’m glad you noticed that! Some people thought it was a little gimmicky, but it was meant to sound like bullets or explosions, especially during the closures. It added some drama to the songs.

Mystery solved, then. So, the record came out in 1981. How long before that was the band formed, and how many years were you all actively playing?

We started talking about it in January of ’79 and got together pretty quickly after that. We played actively for about five or six years—up until around 1985 or 1986—before life caught up with us. Kids, finances, and responsibilities eventually took over.

And do you still keep in touch with everyone?

Yeah, we still see each other. Unfortunately, Joey passed away, and our original guitar player, Buzz Fetters, had a terrible accident with a power saw. He lost some of his fingers, which was devastating. That’s when we had to bring in another guitarist to move forward. Buzz played on the second album, though.

That’s heartbreaking. Losing your ability to play guitar like that—there’s nothing worse for a musician.

Yeah, it was tragic. Buzz was incredible, and you can’t replicate what he brought to the table. All the guys in the band were phenomenal players.

When you were playing live, you were sticking mostly to tracks from this album, the unreleased second album, and a few covers. That about right?

Yeah, that was absolutely it.

Is there a story behind the recording of the album? Do you remember anything specific about the equipment, the producer, or how long it took to record?

Well, we recorded it at Relayer Recording Studio, which we eventually bought. At the time, it was a bit of a juggling act because we all worked day jobs, and the engineer couldn’t always be there. The delays were crazy, so we just went ahead and bought the studio. It had a Tascam 688—a 1-inch 8-track recorder—and a huge Tascam mixing board. We used a lot of RE-20 mics and effects like the Eventide harmonizer, which was such a sweet piece of gear.

It wasn’t a big fancy setup, but it worked well. We even recorded church groups in there—it was that versatile. To make the album, we’d head into the studio at crazy hours, sometimes 3 a.m., and put in about 40 hours recording and another 30 mixing. And, of course, there was a lot of beer involved.

Honestly, it was just so much fun. I wouldn’t change a thing about how it came together. We were lucky to have the financial backing to make it all work. It was like living a little dream.

What about the cover artwork?

Oh, the cover artwork was done by Nick Braidoff, a dear friend of mine who, sadly, has passed away. Nick was a carpenter by trade but an incredible artist—renowned in Deland. One night, over drinks, I asked if he’d do me a favor and design an album cover.

He painted the original on a 12-by-12-foot canvas. It was a masterpiece. He even hung it up at the lumberyard and rolled it down for a big reveal. What you see on the album is a condensed photograph of that original painting.

Nick was such a creative force. At one point, we even talked about turning the mastodon on the cover into a fiberglass mold with smoke pouring out of it for our stage shows. That would’ve been wild.

I still have the original painting. We used to hang it at some of our bigger concerts and light it up with fog and effects. The crowd loved it.

That’s amazing. Do you have a particularly memorable gig or two you’d like to share?

Oh yeah, there are two that come to mind. The nicest one we ever did was in Immokalee, Florida. We played a concert for three high schools in this massive auditorium. We brought our whole production setup—lights, flash spots, the works—and the kids went nuts. That energy was unforgettable.

The craziest gig, though, was when our agent booked us at this place called the Zodiac Club in Daytona. We didn’t realize until we got there that it was a gay bar. They set us up by the pool, and, well, let’s just say it was a bizarre experience. Without going into too much detail, it was unlike any other crowd reaction we ever had.

We had a long talk with our agent after that one—made it clear we didn’t want to do anything like that again. But it was still memorable in its own way.

What would you say was the highlight of your time in the band?

For me, the highlight was always performing ‘Rock and Roll All Night.’ The drums kicked it off, and the crowd would go wild. It was usually our closer, and we’d throw in some extended solos to take it to another level.

There’s another song on our second album called ‘Saturday Night’ that I think will blow people away when they hear it. But yeah, ‘Rock and Roll All Night’ was always special. That one, and honestly, everything on that first album—it all holds up.

You know, when you perform, you play the album all the way through—from Side A, Track 1 to Side B, closing with ‘Rock and Roll All Night.’ That must be a satisfying set.

Yeah, I enjoyed that. Playing it through like that felt cohesive, like telling a complete story. For me, being in the band was all about the opportunity it gave us—the people we met, the experiences we had, and, most importantly, the joy we brought to others. That was the goal, really.

It sounds like a meaningful chapter in your life.

Absolutely. I’ve always believed that music, especially ours, is timeless. It might not resonate today or tomorrow, but eventually, it finds its place. It’s ahead of its time in a way. That’s why I’m so grateful we connected and that you’ve reissued the album. It’s exciting to think about a new generation discovering it.

I’m glad we made it happen. It’s great to see Mammoth getting the recognition it deserves. Did you or any of the band members continue with music after Mammoth? And what’s keeping you busy these days?

These days, I own a large lumber and building materials operation here in Central Florida. But music is still a big part of my life. I play in a band called OMT—stands for One More Time. We’re pretty laid-back now, focusing on charity performances.

That’s amazing.

Yeah, the musicians in the band are top-notch. We’re all seasoned pros, just giving back to the community. I don’t think I’ll ever stop playing until the good Lord calls me home. Music’s in my blood. Once you’ve put in the time and effort, you can’t just walk away from it.

That’s true. It takes so much dedication to get good at an instrument. Walking away isn’t an option once it’s in your bones.

Exactly. If you don’t use it, you lose it. You have to keep it sharp.

Well, Ron, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me. As always, with my interviews, the last word is yours. Anything else you’d like to share before I hit stop on the recording?

Just this: I believe everything happens for a reason. Us connecting here today, it’s no accident. Maybe we don’t know the full purpose yet, but there’s a reason for it. Between you, the reissue, and everything else, I’m just blown away by this opportunity. God bless you for what you’re doing. Stay in touch, and let’s see where this journey takes us.

I can’t wait to hear that unreleased album and see the footage you’ve mentioned. I’ll be in touch again soon.

Thanks, bud. I hope you can make something out of all this.

Lance Barresi

A very special thanks to Lance Barresi for making this happen.

Permanent Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

RidingEasy Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / Tik Tok / YouTube

Thanks for unknown. Already ordered.