Sky Fire | Interview | The Missing Link Between Sudden Death and Hammerhead

Sky Fire, a band that bridged the gap between Sudden Death and Hammerhead, was a more refined version of the former, with a more commercially-minded approach.

The story of Sky Fire is finally being uncovered thanks to its ties to Sudden Death. Consisting of John Binkley (bass), Greg Magie (vocals), Keith Winnovich (guitar), Dave Morgan (keyboards), and Charlie Brown (drums), Sky Fire emerged in 1973 after Sudden Death had struggled to secure a regional following, despite their ties to Kim Fowley.

In an attempt to break into clubs that considered Sudden Death too loud and psychedelic, the band reimagined their sound into a more accessible, centric rock style, making sure to avoid the usual clichés. About 60% of their setlist was built around original material and covers that stood out from what others were playing. This new direction also led to the creation of ‘Heavy Metal Kids,’ a track that caught Kim Fowley’s attention once again, though it ultimately didn’t lead to any concrete opportunities. After a year of performing, Sky Fire eventually dissolved, with its members moving on to other projects, including Hammerhead.

While they may not have achieved the lasting recognition of their peers, Sky Fire’s story sheds light on the never-ending amazing underground scene.

“We had one original, ‘Heavy Metal Kids,’ that we wrote specifically to spark Kim Fowley’s interest.”

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

John: I went into detail on this in my Sudden Death interview, so I won’t repeat it here. The short story is that I grew up in Pasadena, California, and music was indeed a part of my childhood. My parents played piano, and my dad played trombone. I sang in a church youth choir. I took piano lessons starting when I was six and trombone lessons when I was twelve. I played trombone in demanding music programs in junior high school and high school bands and orchestras. I was thirteen when I discovered rock and roll in 1963, thanks to The Beatles erupting on the scene.

There was no real music scene in Pasadena for a kid in junior high school—no local bands to speak of, no teen clubs. But this was Southern California, so there were concerts. Some were silly, like seeing Herman’s Hermits, The Turtles, and Freddie and the Dreamers at the Rose Bowl, where the crowd was confined to the lower half of two sections of the stadium, and a very temporary stage had been built on the football field’s sideline. Some were amazing, like seeing The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl and again at Dodger Stadium (their next-to-last-ever concert) and, on another occasion, Hendrix opening for The Mamas and the Papas at the Hollywood Bowl. When I got into high school, promoters had started booking bands every week in the Pasadena Civic Auditorium’s Exhibition Hall with acts straight out of San Francisco’s Avalon and Fillmore auditoriums. So even though I wasn’t yet in my first rock band, I was being inspired by some very powerful acts. I wanted to be part of it.

Keith: I was born in 1950 in Palo Alto, about 50 miles south of San Francisco. We were not what you would consider a musical family. My father liked symphonic music, mostly turn-of-the-20th-century composers like Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Ravel, and Sibelius. As he got older, he listened to Simon & Garfunkel, Neil Diamond, and Earl Klugh and even went to see Richie Havens at Stanford. My mother was from a family of sharecroppers in South Georgia. She liked Mahalia Jackson-type gospel and various country artists.

Dave: I was born on December 11, 1949, and raised in Enterprise, Oregon, the seventh of ten children. All of us had to take two years of music lessons on an instrument of our choice. I took piano lessons when I was eight and nine. I wasn’t very good and generally disliked the lessons until I discovered I could memorize a whole song after two or three times of playing it correctly! By eleven, many of my friends were in the band at school, so I joined and played trombone for the next eight years. Upon graduation from high school, I went to Oregon State University to study electrical engineering.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

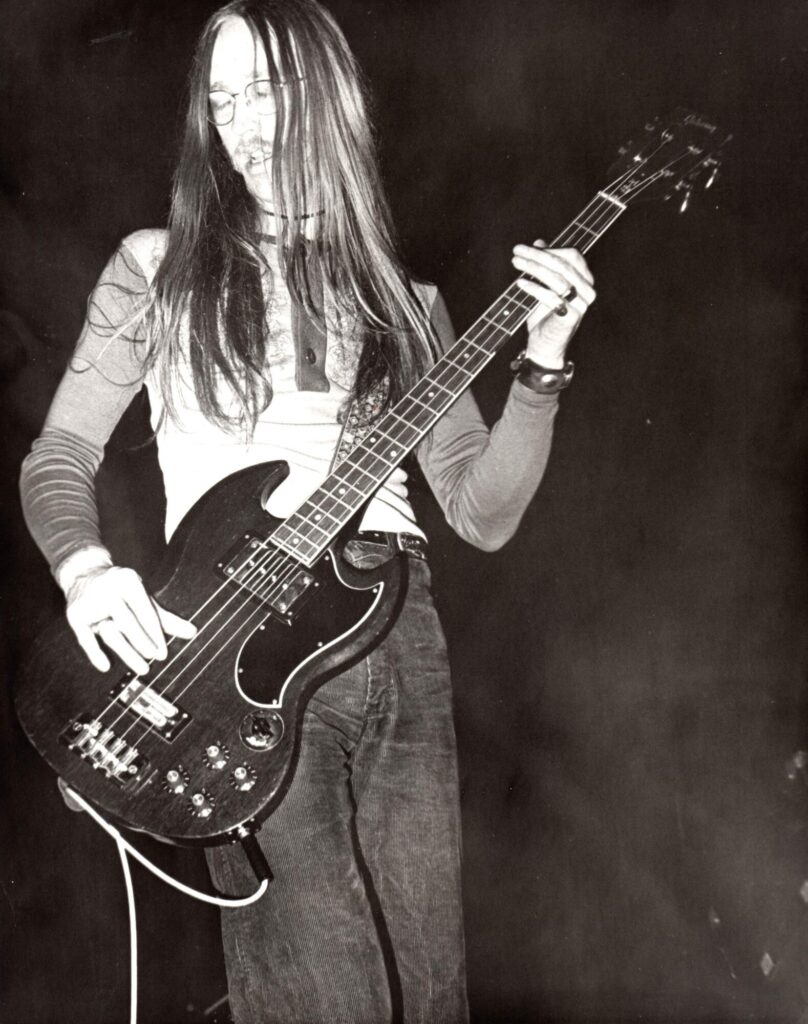

John: Other than my early instrumental training, my first “rock” instrument was a plastic ukulele. Seriously. I used it to learn the most simple Paul McCartney bass lines. Then I got a second-hand acoustic guitar and continued to learn bass lines by ear to everything on the radio. I traded that guitar to a guy I met one summer in Newport Beach for a hollow-body Kay electric bass and bought a Silvertone Twin Twelve combo amp from my barber. Soon after Sudden Death came together, I stepped up to an Ampeg bass amp, and soon after that, I replaced the Kay bass with a Gibson EB-3L. But it all started with that ukulele, which I still have.

I started listening to Top 40 radio stations in Los Angeles to learn songs by The Beatles. But the British Invasion brought new influences: Them, The Kinks, The Who, The Rolling Stones, then The Doors, Jefferson Airplane, and Hendrix. So-called “underground” FM stations emerged, such as KPPC, and they gave lots of airplay to the likes of Blue Cheer, Iron Butterfly, Vanilla Fudge, Cream, early Pink Floyd, Procol Harum, Jethro Tull, and so many others. At that point, I was buying albums and figuring out bass lines as fast as I could, all before I started playing in bands.

Tim Lavrouhin was a drummer I had known in high school who became the original drummer in Sudden Death. He and I went to as many concerts as we could afford. There was so much going on by 1970 that it was exhilarating.

Keith: I began playing trumpet when I was nine years old. It was for school, and I had thought the violin would be fun to learn. Of course, the violins were all gone by the time I got to choose. I picked the trumpet (after all, I was told the violins were better for girls than boys). At least I learned to read music and later came to appreciate having the ability.

I have a brother who is four years older, so he became my initial influence through his choices. They were mostly Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Buddy Holly, and the like. I remember having Johnny Cash’s first album and using that to start playing. I used an early ’50s Harmony Archtop my uncle loaned to me when he joined the Air Force. Never gave it back. When Bob Dylan’s ‘The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan’ came out, my brother’s friend loaned it to him. Although I was attracted to folk and surf music and began to roughly hone what skills I had, Dylan, The Beatles, and The Byrds became the dominant influences.

Dave: When I was five, I joined the children’s choir at church and then took piano lessons when I was eight and nine. I tried learning guitar several times around ten and eleven years old, but it hurt my fingers too much. I later learned the guitar had been set up for slide guitar by an older brother. At eleven, I joined the high school band (it was a small school), and I played trombone until graduation. This taught me the bass clef. During this year, my family was at a cookout with the Sons of the Pioneers, whose main tenor was a family friend. Singing around the campfire with a couple of guitars and their voices stirred my desire to again try to learn guitar.

In 1968, at Oregon State University as an engineering student, I was assigned to operate the PA system at the main auditorium. My first experience was a Grateful Dead concert. I was able to see up close Phil Lesh’s bass setup and then received another insight into “psych”; the Dead had me turn on the house PA (the one I was responsible for) only after they took a short break! This made everyone feel like the band had just gotten even better. I also ran the sound for Simon & Garfunkel, Dionne Warwick, Al Hirt, and Judy Collins concerts.

What bands were you a member of prior to the formation of Sky Fire?

John: I had been the bass player in Sudden Death from its inception in 1970 until singer Greg Magie, drummer Charlie Brown, and I left in early 1973 and formed Sky Fire.

Keith: My first band was a surf band called The Riptides (still a good name). The second was called The Good Wurd (sounds religious). The drummer, Akita, was of Asian ancestry, and his father was a Buddhist minister who was interned during WWII. A wonderful family. Akita went to Harvard and eventually to the New England Conservatory of Music. He still plays and has released numerous CDs. I haven’t seen him since 2008, but I played with him and Jimmy Williams (a San Francisco jazz singer) at the time.

Following that was Ground Sage (it was a spice thing, I guess). Our claim to fame was playing just before the Grateful Dead at a “Be-In” in Palo Alto. It was at a time when they released their first album. I had met Jerry Garcia at the local music store where he taught guitar and banjo. I didn’t know him well, but he was always willing to give you some tips when you saw him. At the time, I was about fourteen and had been introduced to the music of Buddy Guy, Howlin’ Wolf, and Sonny Boy Williamson through an older friend who was a guitarist.

Can you elaborate on the formation of Sky Fire?

Dave: Early in December of ’72, I flew to Los Angeles, rented a Hammond B-3, and auditioned for a spot in Sudden Death. They were unimpressed but failed to inform me they only did originals, which they didn’t have recordings for me to get familiar with—a waste of time and money for me. A month later, in January ’73, my wife and I moved to L.A., where I continued taking electronic engineering classes. We stayed with Greg Magie for a few weeks, then rented a house with a garage big enough for a band to use for rehearsals. I moved my B-3, Leslie, and sound gear into the garage and went to school. A week or so later, Greg came over and told me Sudden Death was dead! I really liked that band but personally wanted all the players in a modified band style. That was not to be.

A couple of weeks later, the new band showed up for our first three or four practices over the first two weeks. We then lined up five or six auditions but didn’t get any gigs. We rehearsed for a couple more weeks and, finally, got a gig.

I met Keith Winovich at our first practice and immediately liked his attitude, personality, and playing. He gave me a copy of his original tunes, and I knew this was gonna be a lot-o-fun! They weren’t rock-and-roll but had a very classy Cat Stevens feel—who is one of my favorite songwriters. In an effort to upgrade his sound, Keith bought a cutting-edge GMT amp, which blew up after a few gigs. I called the factory…

John: Which, at that time, was Bob Gallien’s garage!

Dave: …and received permission to repair the amp, as it had overheated output transistors that were not installed properly. Boom, we were up and running again. Years later, I met Bob Gallien at the factory, and he still remembered that phone call. You gotta have an engineer in some of these technical bands.

Keith: I was in L.A. trying to get solo work. Never became a good enough songwriter. Went to Island Records, A&M, Elektra, and others. Did some random work at A&M and Hollywood Sound Recorders. I ended up meeting Greg Magie at Musicians Contact Service and thought I could give it a try. I had evolved back to a more folk and folk/rock niche, but the metal was not far off. I had also maintained a blues streak with more English progressive rock (Jeff Beck, Yes, and David Bowie). The unrestrained, loud classic rock was fun, and that’s where my head had settled.

John: Sudden Death ultimately reached a point where it became evident we would never find steady work playing in the Los Angeles club circuit. We had auditioned and auditioned, but even clubs whose owners really liked the band wouldn’t book us on weekends (“You guys are great, but…”).

The Epic Records experience elevated our hopes, but when they informed us that they were not going to sign Sudden Death, the primary reason they gave was the lack of a regional following. Joey Dunlop, our guitarist, wasn’t willing to compromise on the music and felt that if we stayed on track and developed more originals, other opportunities would come. English Cathy, our manager, felt the same way. But Greg, Charlie, and I felt that getting into the clubs was an essential step that we had failed to achieve and that doing so would more quickly bring attention to the band. We knew we were at an impasse with Joey, but we carried on for another six months or so before things broke down.

A key factor was the arrival of Dave on the scene later that year. He was the younger brother of one of the occupants of the house in South Pasadena where Sudden Death rehearsed and partied. Dave had serious chops on keyboards, he had a Hammond B3 and knew how to use it, he had been successful on his home turf, and he was eager to make his mark in Los Angeles. He had a house with a garage that he was willing to use for rehearsals, and he wanted to play club-palatable hard rock, which had initially ruled him out from joining Sudden Death. So when it became clear that Sudden Death’s issues couldn’t be resolved, the three of us teamed up with him and started looking for a guitar player.

As he said, we found Keith through Musicians Contact Service. He wasn’t a hard rocker in the same way Joey was, but he was a super-talented guitarist who drew exceptionally well from a much broader palette of musical styles. Keith turned me on to Mahavishnu Orchestra the way Joey had turned me into a Deep Purple fanatic. He brought more to Sky Fire’s power and performance than we had expected, so we were ready to roll.

How did you initially meet Kim Fowley?

Dave: I initially met Kim when English Cathy, who had managed Sudden Death, was on the way to coach Van Halen on backup vocals. The next time was at a Battle of the Bands in Pasadena, in which, rather than as a competitor, we performed as the featured headline act.

Keith: I met Kim at his apartment at Chateau Marmont. We, as a band, had not discussed writing originals. I would have been up for that, as there was a big riff-rock writing approach that was becoming dominant in the market. Kim introduced us to several songs that were somewhat embarrassing. He had, however, gained notoriety in L.A.

John: I first met Kim Fowley while in Sudden Death. Kim was a co-producer of the now-legendary Sudden Death demo for Epic Records. When Greg, Charlie, and I moved on to Sky Fire, Kim’s interest followed us. He didn’t do for Sky Fire what he had done for Sudden Death. That is, he didn’t generate enough record company interest in us to lead to a demo. But he encouraged us to think in terms of doing originals, and we knew what he was capable of doing for a band.

For Sky Fire, originals were not of immediate importance. Our focus was getting into clubs, and to that end, we were carefully selecting covers to execute. So Kim didn’t see us in the same way he had seen Sudden Death. But he was there.

Have you ever heard about a band called Hollywood Stars?

The Hollywood Stars formed thanks to Kim Fowley, who had this idea of combining ’60s pop with the attitude of hard rock. Fowley described his concept as a West Coast version of the New York Dolls, and he set out to find musicians who would fit the bill. After the project was born, I guess something similar happened with Sky Fire?

Dave: All I knew about the Hollywood Stars was that it was an idea Kim had.

John: I was definitely aware of the Hollywood Stars, but I wasn’t close enough to the project to have first-hand knowledge about them. Kim was doing what Kim did—looking for existing bands or creating ones that he felt he could promote to record companies and cash in on the publishing royalties for their music. And Kim was especially interested if they had a gimmick. He was always looking for something, other than the music, that would make a band stand on their own—an angle. That’s how The Runaways came into existence, along with other projects that he pushed.

Sky Fire wasn’t put together by Kim, and we hadn’t developed a gimmick that Kim considered marketable, but the three of us from Sudden Death (Greg, Charlie, and myself) were on his radar, and he showed a lot of interest in what we were up to.

At one point, Kim had me audition for a band he had been trying to put together, although I don’t remember the band’s name—if they even had one at that point. What I do remember is that they had been working with a bassist who didn’t know how to tune his bass properly. Seriously. I came into their studio, set up my equipment, dialed in my sound, and asked the guitar player for an E. The place went dead silent, and everyone stopped to watch and listen to me tune. I didn’t get the gig, though. I guess being able to tune up wasn’t enough for them.

Tell us about some of the early gigs you played.

John: As soon as Sky Fire had a sufficient repertoire, we started auditioning, and we achieved our goal of getting hired in L.A. clubs. We played at Pier 52 (now known as Baja Sharkeez), just half a block off the beach in Hermosa Beach. We played The Blowout and The Bumper Yard in Torrance (more on that later). We appeared at the Pacific Ballroom in Long Beach, which, instead of a traditional rectangular stage, had a round, rotating stage partitioned into three sections, with a band in each section. When your set was over, the next band rotated into place. Then there was The Attic in the Venice Beach area, which would eventually book the likes of Hammerhead and Van Halen.

Dave: One of the earliest gigs we played fell on the day the newly built Glendale Freeway was set to open, and, being from Oregon, the guys thought I would like to have a snowball fight on our way home. Fool me once… Anyway, it was true—the freeway had tons of snow and was shut down, and we did throw a few snowballs.

John: We played at a large, upstairs club adjacent to the Long Beach Auditorium on nights when Deep Purple and other major acts were in the auditorium.

Dave: War was another. Two of their horn players sat in with us after their concert concluded. Some drunk girl parked her lit cigarette on the top of my B-3. I smelled something burning just as one of the horn players spotted it, but the damage was done. I now have a two-inch burn mark—a “battle scar”—on my $5,000 keyboard. Live and learn!

John: Best of all, we succeeded in getting booked at the crown jewel of cover band clubs in Los Angeles: Gazzarri’s on the Sunset Strip, a block away from the Rainbow and Roxy, and just a short walk from the Whisky. Gazzarri’s was so popular that there would be a line of kids outside within an hour of the club opening. It had a sizeable downstairs with a dance floor, booths, a bar, and two distinct stages for bands, along with wings off the stages along the walls for dancers who wanted to show off. There were follow spots and closed-circuit video to highlight dancers and musicians. The room was big enough that there was a balcony running around three sides of the club upstairs, with another stage. When the club was packed, it was quite a scene. And when you walked outside for a break, you were on the Sunset Strip. It was something else.

Working at clubs like that, word of mouth got us gigs at private parties, singles’ apartment complexes, and teen centers.

“We had extensive jams on a few songs and a tremendous “walk-in build-up” on Foghat’s I Just Wanna Make Love to You”

How much of your own material did you have? What did your repertoire consist of?

John: We had one original, ‘Heavy Metal Kids,’ that we wrote specifically to spark Kim Fowley’s interest. He liked the song a lot and tried to shop it around, but nothing came of it. I don’t remember us having any other originals. Carrying over songs from Sudden Death seemed counterintuitive to our goals for Sky Fire.

That said, we tried to blend good hard rock with more mainstream covers. And remember—we had Dave on a Hammond B3, so we could generate a huge sound. We did Deep Purple (‘Highway Star,’ ‘Smoke on the Water,’ ‘Woman from Tokyo’). We did a Jo Jo Gunne song (‘Take Me Down Easy’). We did Argent (‘Hold Your Head Up’), Alice Cooper (‘No More Mr. Nice Guy’), Jethro Tull (‘Teacher’), Spirit (‘I Got a Line on You’), Spooky Tooth (‘Better by You, Better Than Me’), Steppenwolf (‘Born to Be Wild’), and Uriah Heep (‘Walking in Your Shadow’), to name a few.

Dave: We did hard rock covers by Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Sly, Hendrix, Bowie, Uriah Heep, Free, Procol Harum, Bad Company, Steely Dan, the Doobie Brothers, Foghat, Kim Fowley, and many more.

We had extensive jams on a few songs and a tremendous “walk-in build-up” on Foghat’s ‘I Just Wanna Make Love to You.’ The best lead-in and exit jams were on The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me.”

On New Year’s Eve, 1973, we were playing the Pacific Ballroom in Long Beach when our manager, English Cathy, requested that we let the Van Halen brothers sit in on one song, as she was thinking of booking them and needed to see if they could handle the stress of performing in front of thousands. As I recall, our drummer Charlie knew Alex and immediately agreed, and Eddie brought an adequate amp and guitar. I explained to them how this song by The Kinks went with our extended jams, indicating where Eddie’s lead comes in, followed by my synth lead, and then Keith’s lead, which was always the strongest.

The Van Halen brothers made it their first hit three years later! We were cutting-edge and tight. We were “Heavy Metal Kids”!

What are some bands you shared stages with?

John: We never did gigs outside of clubs with other bands. With a few exceptions, like the Pacific Ballroom and Gazzarri’s, we weren’t playing the kinds of clubs that booked multiple bands, and the only concert-type appearances we ever played had no opening acts. It wasn’t until I was in Hammerhead that I began sharing the bill with future stars.

Dave: Didn’t quite get there…

Tell us about “Heavy Metal Kids.” Did Kim Fowley work with you on that track? What was his vision for the band?

John: From the beginning, Kim pushed us to write an original. I think he saw those of us from Sudden Death as capable of writing cutting-edge stuff. So we occasionally included a bit of jamming in our rehearsals while we were developing our repertoire, but it didn’t dominate our time as it had in Sudden Death. I don’t recall if we built the song up from a jam or if Kim gave us a very sketchy idea he had developed for a song. Once we had a foundation to build on, though, we began to rehearse the song and transform it into an energy showpiece. I remember contributing a riff behind the chorus that was a descending one-octave scale, repeated several times and climaxing by descending a full two octaves. It worked really well within the song. Kim was impressed, but as I remember it, he wasn’t involved in the evolution of the song into its final form.

I don’t remember the details of the song, but at the time, I thought ‘Heavy Metal Kids’ achieved what we were looking for in an original. It was, for Sky Fire, a product that reflected the talent of the band, and as such, it stood on its own apart from songs that had come out of Sudden Death. We never went into a studio to properly record it. It’s very likely that we used a simple cassette recorder to capture the song at a rehearsal in Dave’s garage and gave that to Kim. It’s too bad that no recording of it exists, as far as I know.

I think Kim’s vision for the band centered on it being a carry-over from Sudden Death. But we were focused on building a following by getting into clubs, and originals weren’t a priority yet. For that reason, Kim’s interest in Sky Fire didn’t build into outright enthusiasm as it had for Sudden Death.

Dave: We loosely adhered to Kim’s version, as we were really working towards some newer power riffs and sounds. ‘Heavy Metal Kids’ sounded robotic-influenced, and as a synth player, I was jazzed to work with Kim.

Tell us about the gear, amplifiers, effects, and pedals you had in the band.

Dave: Hammond B-3 (customized), Arp 2800 Synthesizer, Leslie 147, Shure SM58.

John: I started out using the same equipment I had acquired in Sudden Death: an Ampeg BT-135 (their first solid-state bass amp) with its matching Ampeg 2×12 cabinet and my Gibson EB-3L bass. No pedals.

But early on, Keith started telling me about some guys in the San Francisco Bay Area who were building a new generation of solid-state bass amps. In time, he and I flew to San Jose, and I deliberately took my Gibson with me to check them out. We went to a music store in Campbell, just outside of San Jose, and for the first time, I came face to face with a beast.

At the time, the amp and speakers were branded GMT, but it was, in fact, a Gallien-Krueger. A 600B, with 300 watts of power, sitting on top of two reverse-loaded folded-horn cabinets with a single 24″ Cerwin-Vega speaker in each. It had bass, lo-mid, hi-mid, and treble tone controls, distortion and presence controls, and a footswitch with a boost switch and another switch that engaged the distortion circuit. It was beautiful and produced an Oh-My-God sound. I was never the same.

The problem was, they were only selling them in a few shops in and around San Jose. When I got back to Los Angeles, I got the number of the company and asked to talk to someone about their availability in Southern California. I was told that they were working on it, but it would be several months before it would be possible. They encouraged me to call back as often as I liked to find out when and where they’d be available. When I asked who I was speaking to, he answered, “Bob Gallien.”

Several months later, I got word that Guitar Center in Hollywood had been sent a shipment, so I took out a loan, hustled down, and bought the identical setup that I had seen with Keith. That became my standard rig for everything I did for years to come.

As a postscript to this story, in the mid-‘80s, I was living 60 miles south of Sacramento, California, and wanted to resurrect my GK amp, as I had been using a 100-watt Acoustic combo I had acquired for doing small gigs and jams. But now, I was getting involved in projects that required more power. So I took the amp to the GK factory in Stockton to get it checked out. I had the pleasure of meeting Bob Gallien, who looked at my amp’s serial number—1913—and told me it had been built in his garage back in the day. He said its serial number had been stamped into the metal frame by hand, probably by him, and that it wasn’t the 1,913th 600B to be built, but the 1,913th GK unit of any kind they had built. They merely stamped each product they built with consecutive serial numbers in those days, without regard for the particular model.

Are there any other recordings of Sky Fire that remain unreleased?

Dave: Yes. The Sky Fire video + reels at LaGrande, Lewiston, Enterprise, etc.

How long did the band stay together? What happened to it?

John: Sky Fire lasted the better part of a year. That year was generally pretty intense—between rehearsing, auditioning, doing gigs, and flirting with Kim Fowley’s interest. But the band didn’t catch on the way everyone had hoped, and under those circumstances, members began to think about moving on.

Our demise was probably accelerated by the efforts of Terry Brent, the drummer who had introduced Kim Fowley to Sudden Death, to recruit me to join his new band, Hammerhead. That led to Sky Fire and Hammerhead alternating weekends at The Attic while I “sat in” with Hammerhead as they “looked for” a bassist. Eventually, I had to choose between the two, and I wound up in Hammerhead.

Dave: Kim wanted to hear us live at a large venue, so he lined us up for a Battle of the Bands in Pasadena. We weren’t in the competition but were the headliner. Kim loved our sound, as I recall, and I believe we played our version of Kim’s “Heavy Metal Kids” before that term was even around!

I had just graduated from college and was offered a partnership with my father-in-law’s electronics shop. I had to decide between staying in the band, which didn’t pay that well, or going back to my long-term goal in electronics. It just came down to economics.

What followed for you and other members of the band?

Keith: I ended up getting my BSEE (Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering) from the University of California, Santa Clara, and retired when I was 62. I still play daily just for fun.

Dave: I went to Oregon/Washington for six years and formed several bands: CRT, Mirage, and BrokenSpoke. BrokenSpoke was a Top-40 country rock band that backed up or opened for many touring country stars. I’ve always had this formula for a three-piece band with a singer out front, which meant I was handling key bass and keys at the same time. It made it easy to control and learn new material in this setup.

In 1975, unbeknownst to me, John Fogerty bought a place near my hometown. The previous owner called me and asked if my band, BrokenSpoke, wanted to back up a friend of his who was a good singer/guitarist. He didn’t say who it was but assured me I would be rewarded!

Fogerty and I hit it off immediately. John had written so many songs—sometimes, he would have me kick off the vocal if he forgot the lyrics. I played a few of my own originals for him, and he exclaimed, “Those are million-dollar hook lines!” Later, his friend and recording engineer, Russ Gary, said the same thing. But alas, I had to make a living and had no time.

My guitarist got a Seller’s Pass to the ’78 NAMM show, where we bought the first MXR 19″ rackmount Digital Delay for $1,000—one of only two sold at the show. I memorized the manual and set it up for vocal doubling and chorus effects. OMG! The overall effect, with reverb and tape echo added, was incredible. We sounded like “Queen” had gone country. Lynn Anderson and John Fogerty loved the effect on their voices. I kept that setup a secret.

Both CRT and BrokenSpoke backed Fogerty up many times between 1975 and 1980. Our last tour was with Lynn Anderson (‘I Never Promised You a Rose Garden’) in late 1980. Touring all that year destroyed my marriage, and my wife moved back to California with our son. I moved to San Diego and got a job as a QA engineer at an industrial camera manufacturing plant called Cohu Electronics.

Lynn Anderson’s guitarist on ‘Rose Garden’ was a tech at Cohu, and we have many tales from working together. While working for Cohu, I flew into San Jose and was able to visit Keith and his wife Linda in Palo Alto. I retired from Cohu after 20 years, but I still see our cameras in every city at most intersections, controlling the lights. Have you noticed how much less you are swearing at traffic lights in the last 10 years? I created six major design improvements in those traffic control cameras.

John: For my part, it was Hammerhead, which became the hardest-working band I was ever in. Keith and Charlie returned to Northern California. Keith and I are still good friends. Greg remained in Los Angeles, and our paths crossed again when he was the lead singer in Sorcery and again in the ’80s when I started playing in bands based in the Venice Beach/Santa Monica area.

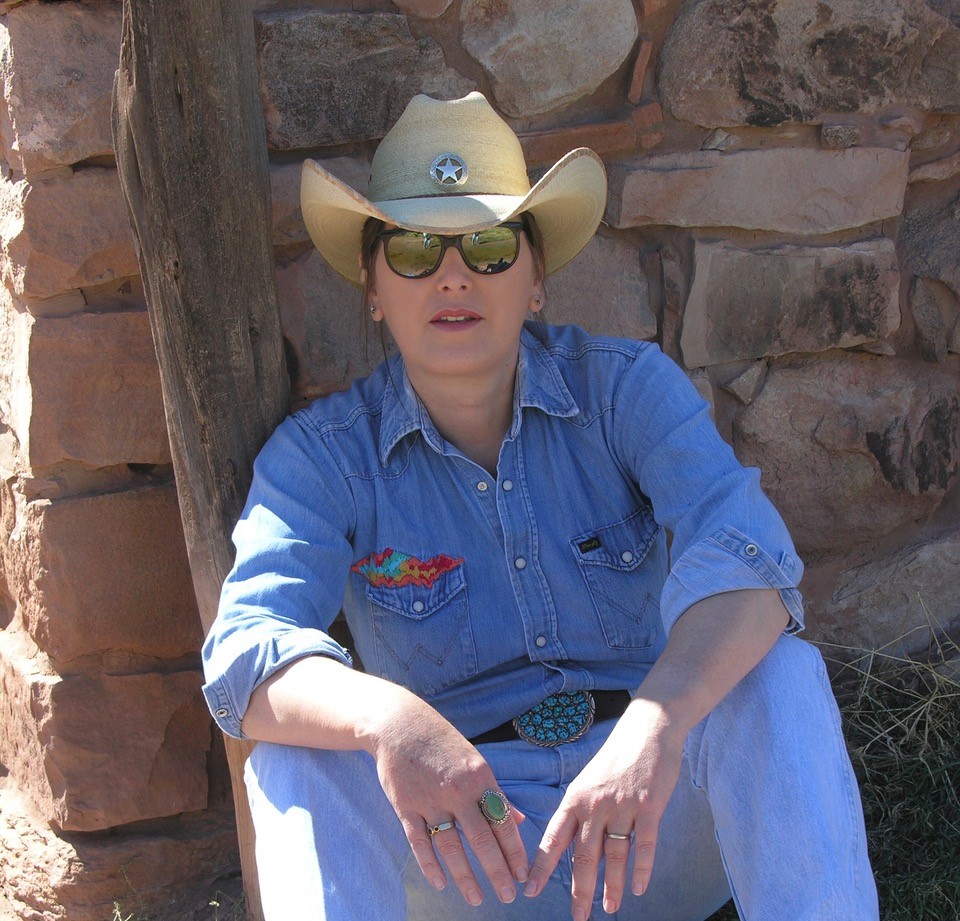

What currently occupies your life?

John: Grandchildren. I’m retired but had continued to play music when opportunities presented themselves until recently. I’d go to jams, get involved in bands when I found a group of stable, dedicated musicians, and write songs. I continue to grow musically and have played live for musical theater shows and cabarets. I support activities surrounding the reissue of the Sudden Death demo by Ancient Grease Records. I’ve been experimenting with performing in Rhythm Infuse with my wife, Ellie, who sings, as a bass and vocals duo using pre-recorded drum tracks. I’m learning to read bass on sheet music and to play with a pick (to spare my fingers). But at the moment, helping to raise our grandchildren takes up most of my time.

Dave: I have been taking care of an older brother with cancer who died recently, so I am just now in a position to design my future.

I currently play in a duo with a fiddle/guitar player. We use a canned drummer (actual recordings of a real drummer) and vocal processing to sound huge. If a duo can sound as big as a four- or five-piece band, people will be blown away! So we have been booked every weekend this summer for really good money, and these people are always very nice.

I did a six-month statistical analysis to determine which weekends in a typical nightclub receive the highest profit. Surprise! The best weekend to play a club (especially if it’s your first night) is the weekend immediately following the middle of the month! The next-best weekend is the first weekend of the month. This is because most people get paid twice a month, and more bills are due at the start of the month, leaving the mid-month paycheck with more entertainment funding in it. Book parties on the other weekends, as they are usually RSVPs. The up-and-down weekend profits look like a sinusoidal waveform. I received an A++ for my statistics grade, and the owner of the club I did the plot on was flabbergasted. So yeah, I guess I am still a scientist.

What would be the craziest story that happened to the band?

John: For me, it was our gigs at the Blowout and Bumper Yard. I don’t know how the club came to our attention, but we pursued the gig without knowing too much about the place.

Our audition was on a weekday afternoon when the club was closed, and although we played well, I wasn’t too impressed. The place was in a block-long strip of stores in the middle of the old oil fields in Torrance. Inside, the decor was surprisingly upscale. There was a nice stage in a corner, a good three feet high off the hardwood dance floor, with a five-foot-deep wing along one wall. The bar was beautiful, and all the seating was plush booths in red leather accented by richly stained wood. It could easily hold 200 people and had several pool tables at the far end. It was a gorgeous lounge, and it was hard to envision its clientele being into our music.

But the owner said his crowd would love us and booked us. We went down Friday afternoon, set up, and did a sound check. There was nobody there except the manager, who was cleaning up.

When we got there Friday night, we wondered what kind of neighborhood we were in. The strip mall’s parking lot was lined with immaculate Harley-Davidson choppers. Then we went inside and found the club packed to capacity with bikers—heavy-duty, seriously dangerous, hardcore outlaw bikers—and the vibes were intense.

It turned out that the street the club was on formed the boundary between the territories claimed by the Chosen Few and the Bounty Hunters biker gangs. The biker clubs had negotiated that the club would be considered neutral territory, and the club presidents had squads of bouncers to enforce the peace. We got on stage, started playing, and the place went nuts. In a lot of ways, it was one of the best audiences we ever played to. But they would drink, dance, drink, and then get confrontational, so the enforcers constantly had to step in and calm everyone down. It was strange and tinged with danger.

One night, we were in the middle of playing some Rolling Stones song when one of the bikers climbed up on stage, stood right in front of me face-to-face, a beer mug in hand, and started mumbling something. He looked angry, and I was concerned that I had somehow managed to offend him. I didn’t understand what he said with my amp cranked and the noise of a hundred bikers partying in the club. I leaned closer and said, “What?” and then heard him say, “I feel mean tonight!” as he drained his mug, eyeballing me from 12 inches away. Whoa. I’m thinking I may have to use my bass to toss him off the stage—then had another idea. I turned to my amp, took the pitcher of beer I had for the set, filled his empty glass (all while hammering my bass strings with my left hand to keep playing the song), and said, “Hey, have a beer on me.” He looked stunned, suddenly turned, jumped off the stage, and went back to his buddies. But before he left, he said, “That’s the nicest thing anyone’s ever done for me.”

However, that might be topped by the night we all were arrested. We were playing at Gazzarri’s, where three bands each had their own stage area, and we rotated sets throughout the night. That meant you had 90 minutes between sets a couple of times each night—long enough to go see who was playing at the Whisky or Filthy McNasty’s, or to hang out for a while at the Rainbow.

On this night, Dave suggested we listen to Tales of Topographic Oceans in his car. The album had just been released, and he had it on 8-track. So we piled in his car, and rather than look suspicious on a street just off the Strip, we drove around in the Hollywood Hills so we could smoke a joint and listen to the tape. That went well enough, but when we got back to the club and parked, we stayed in the car for a few minutes longer, listening to the music and killing time before we had to go in for our next set.

The next thing we knew, police officers were knocking on the windows. They got us out of the car, smelled the pot, searched us, and found one joint in a cigarette pack one of us was carrying (not me). So they arrested all of us for “being in a place where marijuana was being smoked” and hauled us off to the West Hollywood police station for booking. My one phone call from jail was to Gazzarri’s, to let them know what had happened and that we wouldn’t be there for our next set.

They put the four of us together in our own jail cell. We weren’t sure what would happen next, but we kept our spirits up and took the opportunity to have a band meeting, make decisions about songs, and wonder if we would be able to play the next night.

Word spread quickly at Gazzarri’s, collections were made at the club, and our wives, girlfriends, and closest friends bailed us all out within a few hours. In the end, all the charges against us were dropped, and we were back on stage the next night with a great story to tell.

Dave: The Blowout and Bumper Yard! Or the “after-hours gig” we played in Hollywood, where most of the beautiful women were men!

Greg and I were pulled over by the CHP on the way to a gig in the South Bay area of Los Angeles, right after I had said to Greg, “Let’s not smoke ’til we get there!” I had out-of-state plates that did not match the alleged car they were looking for, and we didn’t smell like weed, so they let us go. I’m sure they saw Greg’s long hair, and that’s why they pulled us over. Hah. Greg and I were like brothers and always rode together to gigs.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

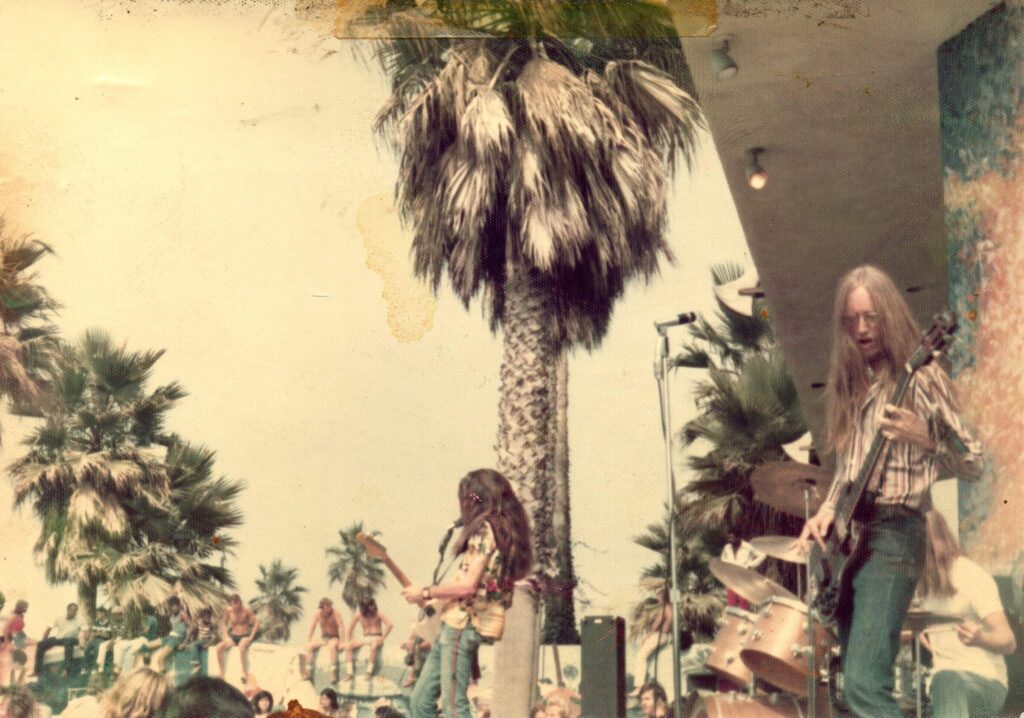

John: The centerpiece of our existence was getting booked by Dave as the headlining act at the Fourth of July celebration in La Grande, Oregon, back on his home turf. He convinced us that if we made the trip, we could fill several weeks of good-paying gigs to make it worthwhile. So we packed up our gear in our cars and made the 1000-mile, 16-hour drive north.

We stayed in the homes of Dave’s family and friends and were immediately treated as celebrities. The local papers were running stories about the L.A. band that was coming to play at the county fairgrounds on the Fourth. We stood out like sore thumbs everywhere we went, which was kind of cool.

Dave hadn’t led us wrong, either. We played gigs in Lewiston and Moscow, Idaho, plus La Grande and Enterprise, Oregon. People were blown away everywhere we went. The gig on the Fourth was packed, and the audience was in awe of the power that we generated. We pulled out all the stops, opening with Highway Star and filling two sets with nothing but our heaviest material. It was kind of the ideal payoff for all our hard work to be a cover band that could bring the house down.

Dave: I remember our first gig with my ARP synthesizer. My brother Henry loaned me the $1500 to buy the synth on one condition: that he got it for the first 24 hours! No problem, as I was in school all day, but I needed it that night. He and my wife fiddled with it all day and decided it was a toy and I had been ripped off. He’s a good piano player, but not an engineer. They couldn’t believe I was still going to play it live that night with Sky Fire. Having read the manual 2-3 times already that day, I tuned it up and blew myself away with how cool, fat, and futuristic we now sounded. My brother never compliments me, but he was impressed; he liked this band, and every night I played with these guys was a treasure. We all had an uncanny sense of what we were doing on stage.

Our gigs in the Northwest were all exceptional, as we were requested to stay over, but had gigs in California to play the next week. I distinctly remember John’s bass solo on Highway Star at the La Grande fairgrounds, as I had played that venue several times in a different band. My friends were blown away! Those people were very impressed and excited as we were getting very tight.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what, in particular, did they employ in their playing that you liked?

Dave: Felix Cavaliere, John Lord, Rick Wakeman, Brian Auger, Steve Winwood, and Ray Manzarek. I used B-3 adjustments from all of them except Ray. I learned the Fender Rhodes and Vox Continental sounds and bass lines from Ray, whom I met when Joey Dunlop and Ray were composing new material. John Lord was always my favorite.

John: I started out completely absorbed in Paul McCartney’s basslines from the first Beatles album on. He made me believe in bass, and I realized that I had the ability to pick out the bass lines rather easily. That led to my Big Three influences: Jack Bruce, John Entwistle, and Tim Bogert. Those guys were monsters on bass, and I religiously bought their albums and worked tirelessly to learn their bass lines, as well as I could, to every song. For better or for worse, I was never a 1/4/5 bassist. You could do so much more. Add into that mix the likes of Noel Redding, John Paul Jones, Geezer Butler, and Roger Glover. Collectively, they showed me what could be accomplished by an aggressive bass player who sees his instrument as a significant and necessary bridge between drums and guitar.

I feel most comfortable in a trio format because I love to fill that sonic void below the guitar with energetic, moving, melodic bass. Tim Bogert transformed me from plucking with my thumb to playing overhand with my index and middle fingers. I didn’t discover Chris Squire until I was in Hammerhead, but he made me realize what could be done on bass when a band adopts an orchestral philosophy for their music. That put me into a highly self-critical phase of playing that has lasted to this day. Not that I was ever in his league technically, but I developed the self-discipline necessary to ensure that what I play is justified by the manner in which it supports the song.

In the late ’70s, I got to meet Tim Bogert. He was involved in Pipedream at that point, and a mutual friend took me to one of their rehearsals. I got to tell him about my transition to playing overhand being due to him, and the memorable night he broke a string early in a concert with Beck, Bogert, and Appice. He was so receptive to my stories that I felt like we were friends. A few months later, I was at a private, premier screening of a film in Beverly Hills, and afterwards, as I was leaving, I heard my name being called. It was Tim, who came across the theater to say hi and introduce me to his wife. She seemed to know who I was and was familiar with the stories I had told Tim. That was pretty cool. My date was very impressed.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Dave: I thought Sky Fire could have been the one because I don’t remember anything negative between the players. Just needed a bankroll to hire everyone away from day jobs! Thank you for this opportunity to remember and write about Sky Fire. They are my brothers!

John: The last word? Growth. Looking back, Sky Fire was a progressive band for its day that played an important role in my growth and maturing as a musician. I don’t think that staying in Sudden Death for another year would have been as beneficial for my musicianship as Sky Fire turned out to be. We played a lot of gigs that required higher levels of performance, perfection, and polish than Sudden Death had needed. With both Dave and Keith, the dynamics within the band were focused and demanding. We didn’t jam and jam and jam: we worked out details and learned lessons from the cover songs we learned, injected them with our branding of solos and energy, and went out to execute them on stage. I polished up my act, and quickly, and proved to myself that I could do it. That was a big step forward for me, and it set the stage for what the future held.

Klemen Breznikar

From Sudden Death to Hammerhead: The Musical Journey of John Binkley

Sudden Death | Interview | “America’s Answer To Black Sabbath”