Afterimage | Interview | ‘Faces to Hide’: Unearthing LA’s Forgotten Post-Punk

Afterimage was never meant to be a long-running act, yet their brief existence carved out a lasting imprint on Los Angeles’ underground.

The compilation, ‘Faces to Hide,’ on Independent Project Records is an archival treasure—a palimpsest of studio recordings, live tracks from legendary haunts like Whisky a Go Go and Al’s Bar, and elusive demos that once pulsed through the veins of a city. Listening to these tracks is like wandering through a musical geography mapped by influences both vast and varied. There are echoes of Public Image Ltd., Pere Ubu, Magazine, The Fall, Patti Smith, and Television, yet Afterimage was never content to simply mirror their forebears; they injected unexpected detours into their sonic journey, weaving surf rock grooves and bursts of saxophone into the post-punk fabric with a reckless, almost sacramental abandon.

Alec’s recollections feel like a heartfelt tribute to a time when music was real—a time when every note stood up against a watered-down present. In this collection, they show us that creativity can still shine even on the fringes of history. ‘Faces to Hide’ captures that passion, preserving the spirit of a band that, even though it was short-lived, still echoes through LA’s underground. This reissue is a meaningful slice of history.

“Experimentation was the currency of the underground music scene”

Alec, Barry, Rich, Holland—after decades of silence, what made you decide to resurrect Afterimage’s old recordings and put out ‘Faces to Hide?’

Daniel Voznick (aka Alec Tension): When Bruce Licher and Jeffrey Clark were reviving IPR, Bruce called me up with the idea of releasing every recording from the original lineup (1980-1982). This was three years ago, and Bruce called me early on because he thought we could get this particular record out quickly. Funny how time marches on.

The post-punk era in L.A. was a wild, chaotic time. How would you describe your band’s role in that scene? Were you more like outsiders peering in, or were you right in the thick of it, shaping the sound and direction?

I think we were in between those extremes. The L.A. scene was large and diverse at that time, and we did not have the connections or the sparkling personalities to become the center of some segment of it. Some of the first wave of punk rockers were still playing. There were quite a few artier post-punk bands, which included Afterimage. Rockabilly had its own scene. New Country had its own venue. The hardcore punk scene centered in the South Bay was probably at its peak. There was a scene in downtown L.A. that was even grittier art rock. We did get noticed by the local press and the fans, though.

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

I can tell you a little about the others:

Barry Craig grew up in Rockford, Illinois. He seemed to have really gravitated toward music from a young age. He showed me a photo of himself at 12 or 14, wildly playing his guitar alongside a similar photo of Elvis doing the same thing when he was young. He made covers for imaginary albums with cover photos and track listings.

Rich Evac came from Florida and studied engineering and perhaps architecture in college. He picked up the bass after he came to L.A. in 1978. He met Holland when they both worked in the property escrow/title insurance industry.

Holland DeNuzzio lived a portion of his life in Iran, as his father was in the foreign service. They moved back to the States for his high school years. I saw a photo of him from that time that looked like he could have been in a Southern rock band—long, straight blond hair. I don’t remember him telling me how he came to the drums.

I grew up in a suburb of L.A., which was a bit devoid of new culture. Led Zeppelin ruled the FM airwaves, and Elton John ruled the AM. The big pastimes at my high school were sports or trying to get some weed or beer. The entertainment section in the L.A. Times covered local rock music about twice a month. Occasionally, they covered something new. I learned about the Patti Smith and Television records that way.

Was there a certain scene you were part of? Maybe you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of concerts back then?

If you’re talking about when I was still in high school, I was outside of any scene or any real knowledge of a Los Angeles music scene. I didn’t have my own car, so exploration was difficult. I only knew for sure that something was going on when Time Magazine did an article in the summer of 1977, just after I had graduated from high school. The article included a picture of L.A.’s Weirdos. But I reckoned if Time Magazine was covering it, it must be over, and I had missed it.

If we stepped into your teenage room, what kind of records, fanzines, posters, etc., would we find there?

I still had a lot of Beatles records. Bowie, Roxy Music, Genesis, and Queen were bands I discovered on my own—Genesis and Roxy Music because I had heard of them and they were in the cutout bin. Later in high school, I got the records of Patti Smith and Television. I had two posters that I can remember—the black and white one that came with ‘The Man Who Sold the World’ album, where Bowie kicks his leg way up, and the one of the stoner whose head is melting in his hands by Robert Crumb.

Please elaborate on the formation of Afterimage.

It happened in two stages. I met Barry in the spring of 1979 (Barry Craig, who went by A Produce on stage—those who knew him would call him either Produce or Barry. He died in 2011). He answered an ad I ran in The Recycler that said something like “New Wave and beyond vocalist seeks band.” When we met, we connected on past bands like The Doors (he was especially fond of them) and contemporary bands like Television, Magazine, and Public Image. He played me The Fall’s ‘Futures and Pasts’ and Gang of Four’s ‘Damaged Goods,’ which were pretty new at the time. He seemed to like my writings, so we started to work together. Not long after, we played a house party where he played guitar, his friend Gary (whose stage name was Pierre Lambow) played synth, and I sang or recited—I can’t really remember. It was not very good or successful, and we moved on to our own pursuits.

Sometime later that year, Barry saw bass player Rich Evac’s ad: “Wanted: Acid-Punk guitarist for threatening Hollywood-based band. Must be fed up and a little sick—no lightweights, hippies, or new-wavers.” Rich knew drummer Holland DeNuzzio, and the three of them got together. Produce passed me the tape they made that day, and I really liked it. We got together sometime later, and it clicked.

Listening to the compilation, there’s a palpable tension between experimentation and accessibility. Tell us about your creative process and the concept behind your sound.

We didn’t really speak of creating a sound—there was no master plan. We seemed to like and be interested in many of the same musical things and stumbled in that direction. Often, we knew what we did not want to sound like more than what we did want to sound like. Usually, at rehearsal, someone would start on an idea they had, and the others would join in. Produce and I usually recorded rehearsals and would glean the most promising ideas, bringing them back to the next rehearsal to develop. I usually had a bunch of lyric ideas and would try them out against whatever was going on. You can hear what some of those nuggets sounded like by listening to ‘Sonic Switch’ on the new record.

‘Strange Confession’ and ‘Satellite of Love’ are standout tracks. Can you talk about the songwriting process for these songs? What were the influences and emotions that drove their creation?

Lyrically, with ‘Strange Confession,’ I was sort of channeling Roxy Music—in a dark way. I think the musical idea was one that the other three had worked on in their first meeting. I just found the lyrics that fit it. I pushed for what we later called the ‘Last Train to Clarksville’ bassline. I would add sax whenever it seemed to fit, and the saxophone really enhanced this song.

The lyrics of ‘Satellite’ came from a particular adventure on the beach. The whole band and a few other friends went to the beach on the Fourth of July, 1980. It was a somewhat secluded spot near the Ventura County line that Produce suggested. Most of us dropped acid that day, including me. Barry had a handheld cassette recorder and a tape of the first Joy Division album. This was the first time I had heard Joy Division, and it was a very intense listening experience while tripping. I was amazed, enthralled, and a little terrified. Produce would come up to me every so often and recite some lyric of mine—almost always the heaviest ones. He was sort of doing this orbit; he kept coming back around. It seemed like that was also happening to Holland and his friend. The idea of satellites circling around came into my head. Either when I got home that night or the next day, I wrote the lyrics for Satellite. It might have even been at the next rehearsal that Produce had that guitar riff, and Satellite of Love was born.

How did Barry transition from Afterimage to ambient music as A Produce?

After the breakup of the original lineup of Afterimage, Produce realized he didn’t need a band to make music when he listened to Stillife ’s ‘Rubrica’ on Contagion Records. Shortly thereafter, he started his Trance Port Tapes label, on which he released his own and others’ music.

The Los Angeles Times once dubbed you “LA’s Joy Division.” How did you feel about that comparison? Did you see yourselves as part of that lineage, or was your music taking a different path altogether?

I was pleased to be considered in their company. I did get annoyed at some writers who would claim or insinuate that we were just copying other bands, as if we didn’t have our own ideas and direction. If you look at the timeline of most of them, we were all contemporaries, acting toward similar goals and reacting against similar trends in the music we grew up with.

The live recordings from Whisky a Go Go and Al’s Bar are fascinating. What was the live experience like for Afterimage? How did your stage presence and performances evolve over time?

We loved playing the Whisky. It was one of the best clubs to play at since the sound was always good, they had good lighting, and a nice stage. Al’s Bar was a different animal. It was very gritty, and, to tell the truth, I cannot remember that gig. We never got to play at my other favorite place to see bands, The Starwood, as it closed before we got the chance.

The way we presented ourselves onstage didn’t really change or evolve much, which is one of the things I regret. As the singer, in front of the band, that was my arena, and from this vantage point in time, I think I could have done much better. The singer is usually the lens through which the band is seen, and I didn’t really project a clear image.

Alec, the saxophone blasts in ‘Strange Confession’ have a unique, almost frenetic quality. What inspired you to incorporate the saxophone so prominently, and how did it fit with the rest of the band’s sound?

I had a friend in college who had been in his high school’s jazz band. He got me listening to jazz, especially Sonny Rollins, whom he really liked. That’s what got me interested in the sax and made me want to try it. Experimentation was the currency of the underground music scene, and the other band members were totally open to whatever I could do with it—and probably with any other instrument I cared to try.

I picked it up for the first time perhaps a year before Afterimage formed. It is a tough instrument, requiring more technique than I could ever really master. I think it could have been even more exciting if I had more chops—the sounds I could have made!

‘Surf Generator’ seems to draw from surf rock influences, which is a bit of a twist for a post-punk band. Was this an intentional homage, or did it emerge from your personal tastes and backgrounds?

‘Surf Generator/Part of the Threat,’ or ‘Surf Threat’ as we referred to it, started with a surfy riff that Bruce Licher came up with. Bruce and I were in a band called Bridge around the time Afterimage formed, and I had come up with a surf-style riff for that band. When he showed me his surf riff (his was better than mine), I liked it and tried it out at the next Afterimage rehearsal. Barry added the keyboard line, and he returned to the next rehearsal with an idea of how to use them together with a song I had called ‘Part of the Threat.’

Although surf music—whether Dick Dale or The Ventures—was not something we listened to or pursued, those sounds were all around in the late ’60s and early ’70s in TV show theme songs. We even added the surf song “Pipeline” to our set for one gig—a Halloween party at the architecture school Sci-Arc. Those folks came to dance that night!

Looking back, is there a particular track or performance that stands out as a favorite or as particularly representative of what you were trying to achieve with Afterimage?

For me, the song ‘Faces to Hide’ shows promise and the expanding direction we could have pursued. I really like the live track from the Whisky with the pounding drums.

The compilation includes a number of previously unreleased demos and live tracks. How do you view these rarities in relation to your officially released material? Do they offer a more authentic glimpse into the band’s original vision?

Being able to share these tracks that were never recorded in the studio or released finally shows the full breadth of the band from that time. We had some nice rough edges that suggested new areas of exploration.

How did Rich and Holland contribute to shaping the band’s sound and direction? And how did their interplay with your vision help define Afterimage’s identity?

Rich would sometimes come up with these weird and interesting basslines—things that got your attention. He was very taken by the interactions of Jah Wobble and Keith Levene in Public Image Ltd. and tried to bring that spirit into our work.

Holland was a dynamic and playful drummer. I say playful because he was always trying something different, searching for an unusual texture. He had a good ear for the memorable and rarely played straight eighths or four-on-the-floor beats.

Produce is still a mystery to me. He really hit some high points, yet sometimes he was somewhere else—somewhere we couldn’t follow. If you listen to his later ambient/trance recordings, you may understand how his thinking was different from a more typical rock musician’s.

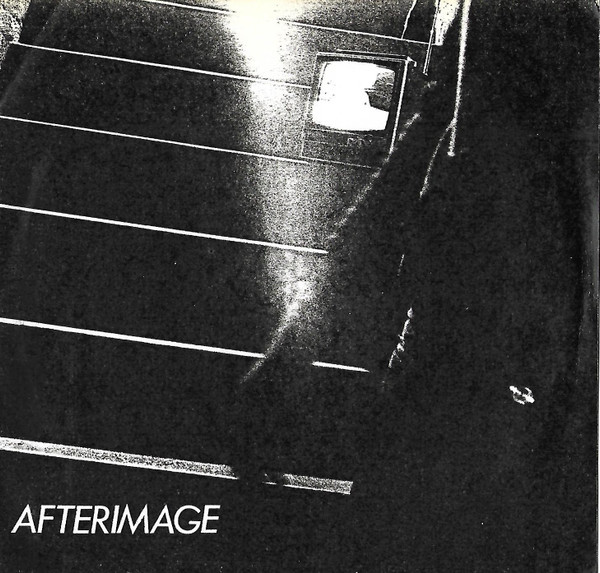

The package for ‘Faces to Hide’ is adorned with custom designs and liner notes. How important was the visual aspect of your music to you, and how did it complement or contrast with the auditory experience?

As an art school student, I was very interested in the visual aspect and created the cover art for the single and the 12-inch. I also designed a few of the flyers when I had the time. Rich, as head of the Contagion label, was really the one who shaped the band’s image through the flyers and other promo material he created. Along with our first manager, Randall Kennedy, he also wrote the press material, which was pretty entertaining stuff.

What was the craziest gig you ever did?

There were several great gigs, notable for different reasons:

Our most fun gig was probably playing a Halloween party at the architecture school Sci-Arc. I had a ghoulish costume on that night, and we added The Ventures’ song ‘Pipeline’ to our set for the first and last time. It was really nice to see so many people dance at one of our gigs.

Our best gig may have been our last gig at the Whisky, playing with Middle Class, Africa Corps (who later became Savage Republic), and Outer Circle. It was a great all-around bill and a fantastic show, featuring songs that are on this latest record but only got played a few times live: “Faces to Hide” and “Idol.”

Our last gig, supporting Suburban Lawns, was memorable because they had the most juice on the local scene at the time. Other gigs that were scheduled but never realized had us supporting The Lounge Lizards and Chrome. Those would have been exciting, too.

What currently occupies your life?

After the original group splintered in 1982, I continued on as Afterimage and released a 7” single, ‘Take My Hands’ / ‘I Can’t Forget,’ and two CDs—’Ghostlight’ and ‘Radio Sky.’ All three are available on the Afterimage Bandcamp page.

I retired the Afterimage name after learning that so many other bands now share it.

Guitarist and keyboard player Barry Craig created the cassette label Trance Port Tapes, which released many cassettes featuring experimental, industrial, and atmospheric music artists. He also began releasing a series of his own ambient/trance music recordings as A Produce. Much of his catalog is still available through Independent Project Records. He passed away in 2011.

Bass player Rich Evac later formed Psi Com, a band that featured future Jane’s Addiction frontman Perry Farrell. He also auditioned for a bass player position in a band with Jeffrey Clark and Grant Lee Phillips, which became Shiva Burlesque. They played some gigs and recorded a demo before Rich transitioned from music to film and TV production. He now lives with his wife in Thailand.

Drummer Holland left the music world behind, got married, and raised a family in the San Fernando Valley.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favorite albums. Have you found anything new lately that you’d like to recommend to our readers?

It’s easy to recall my favorite albums from that time: Wire’s ‘154,’ Pere Ubu’s ‘The Modern Dance,’ Television’s ‘Marquee Moon,’ The Fall’s ‘Live at the Witch Trials’ (first American version), and Gang of Four’s ‘Entertainment!’ were all mind-blowing for me. They were sounds I didn’t expect but quickly came to love. Other very important artists included Public Image Ltd., Magazine, Patti Smith, Joy Division, and Kraftwerk, as well as local bands like The Screamers, Savage Republic, and The Minutemen.

The albums or artists that excite me now are often ones I overlooked while they were active and only discovered later. Sadly, I rarely hear something these days that truly moves me—but that may just be a product of a busy life.

Thank you. The last word is yours.

I’m delighted that there is growing interest in the music we made. I hope it finds a new audience who can connect with its edgy pop/experimental aims.

Klemen Breznikar

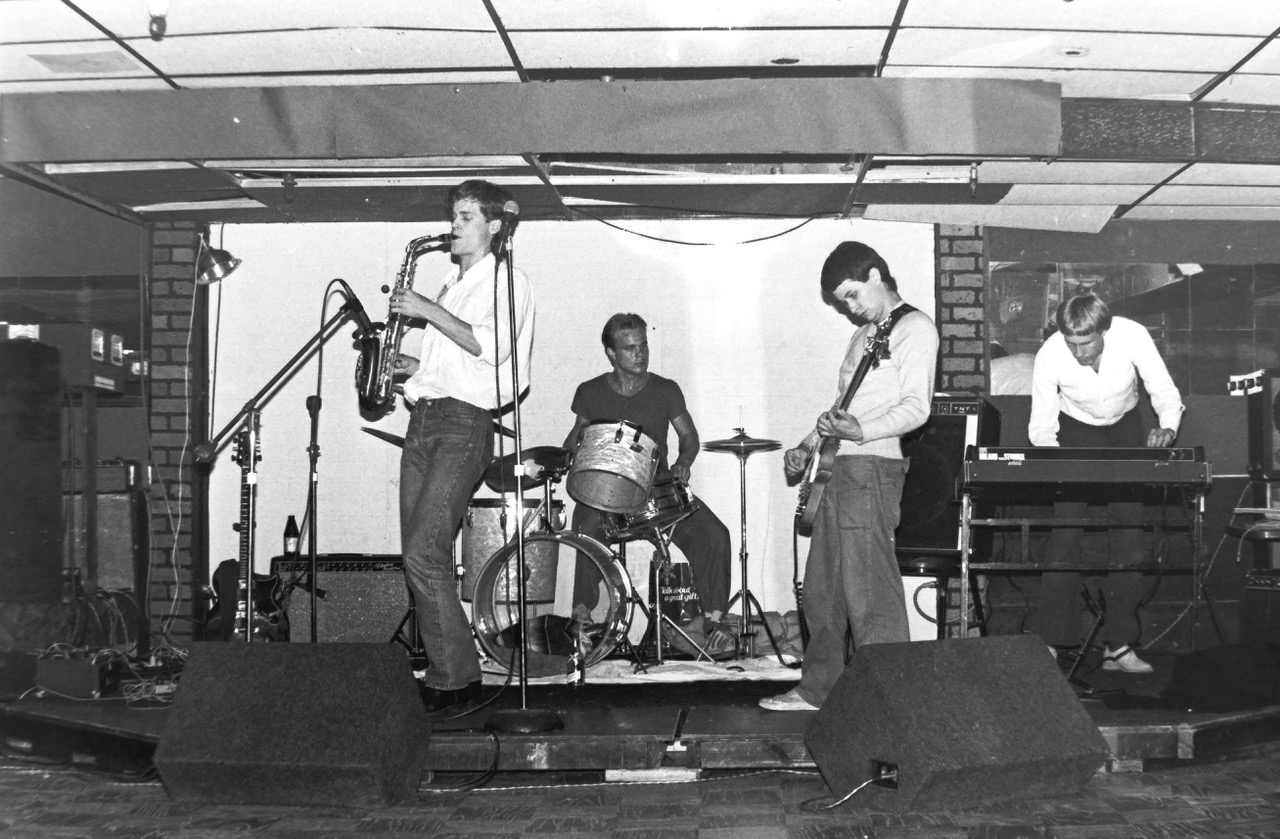

Headline photo: Afterimage | Photo by Mariska Leyssius

Afterimage Website

Independent Project Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

Thank you