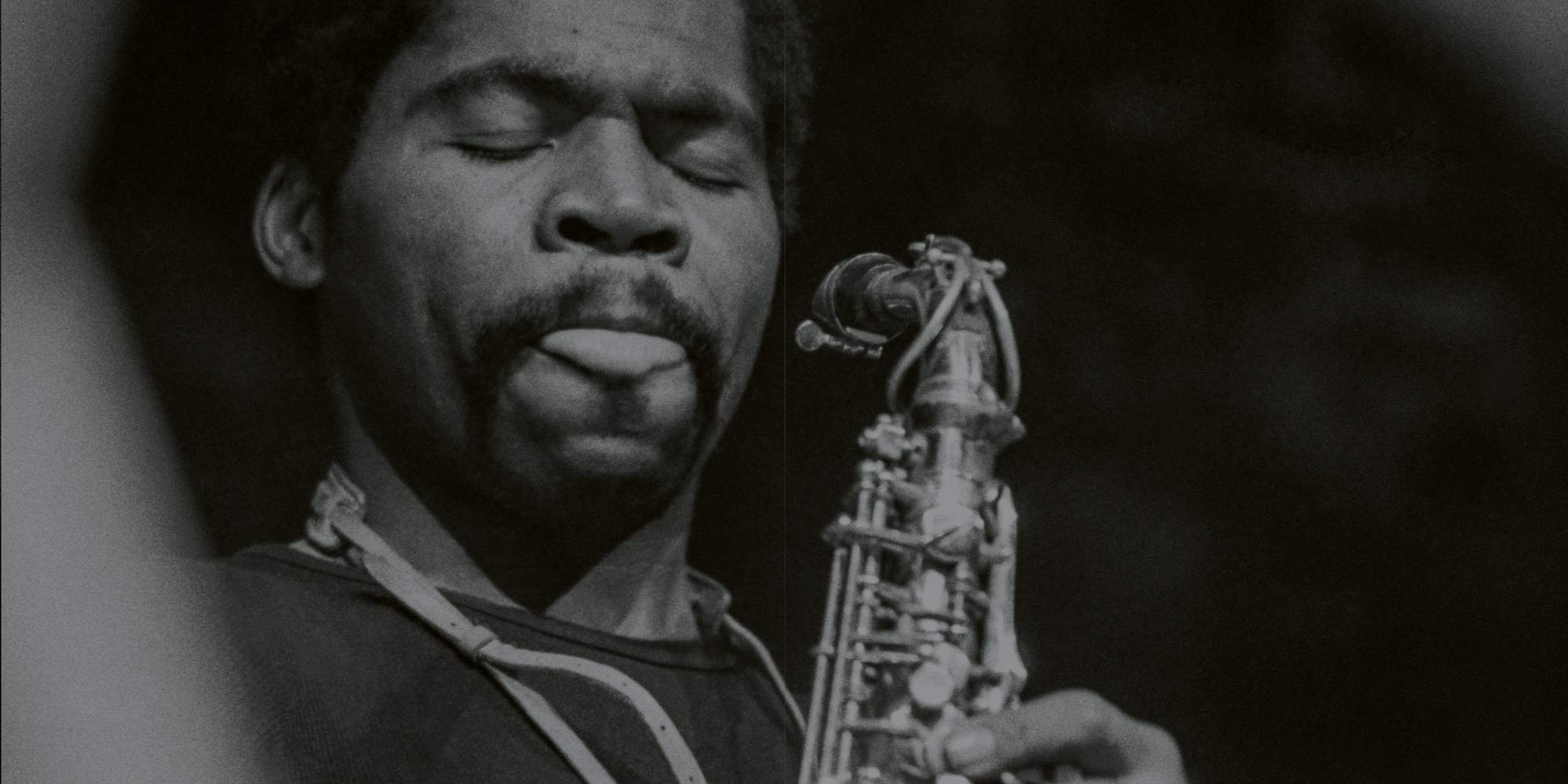

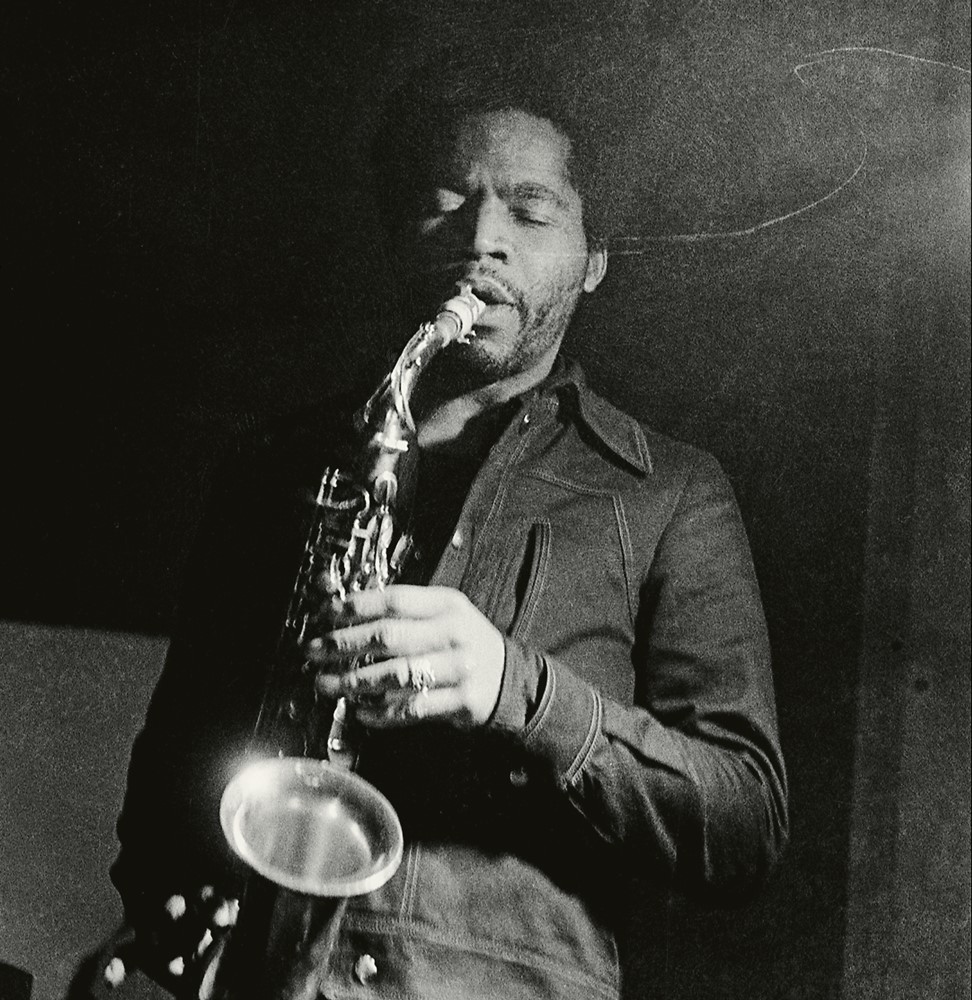

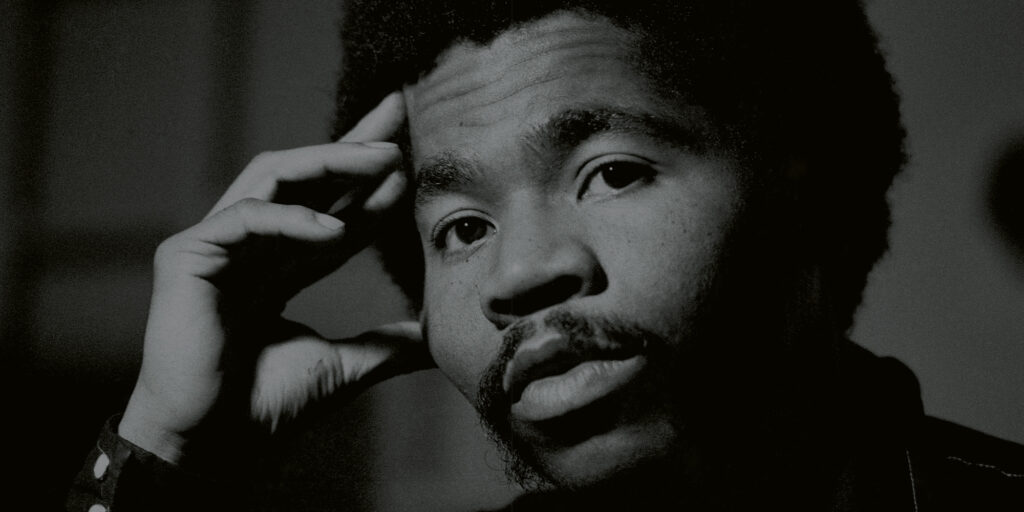

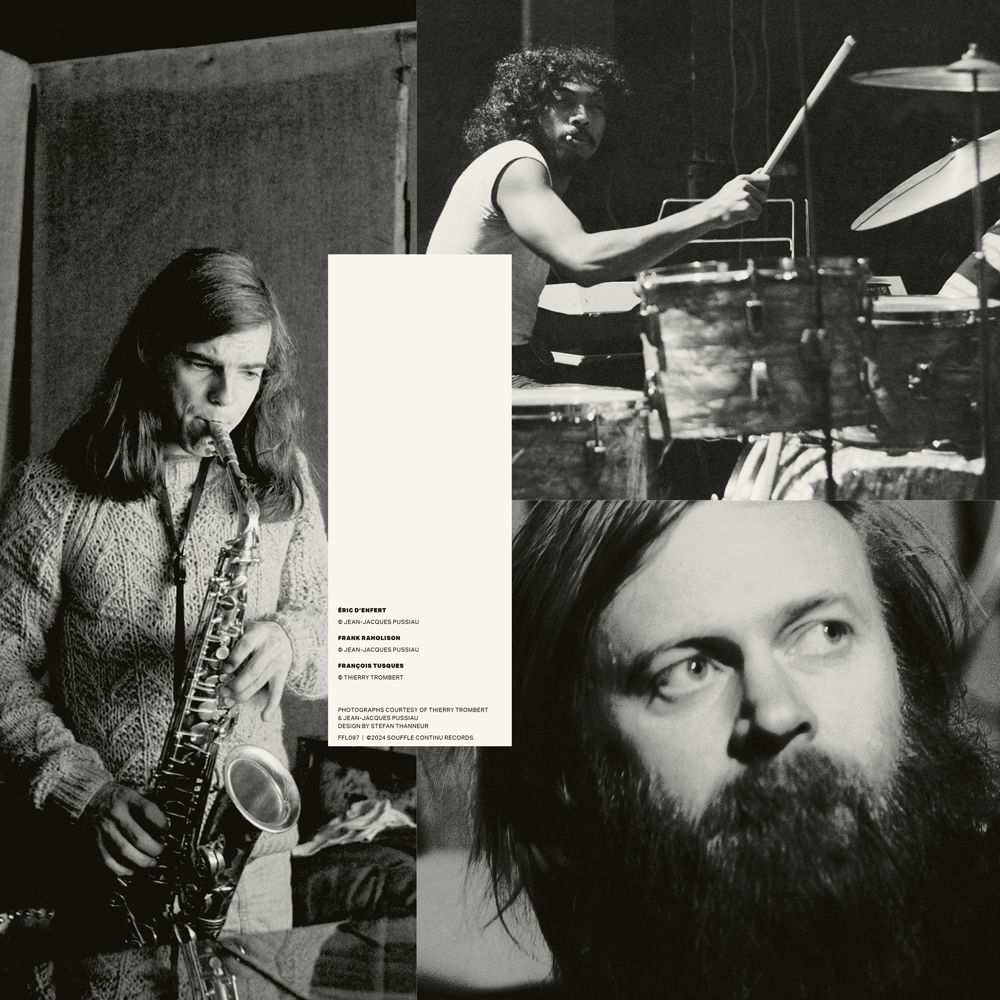

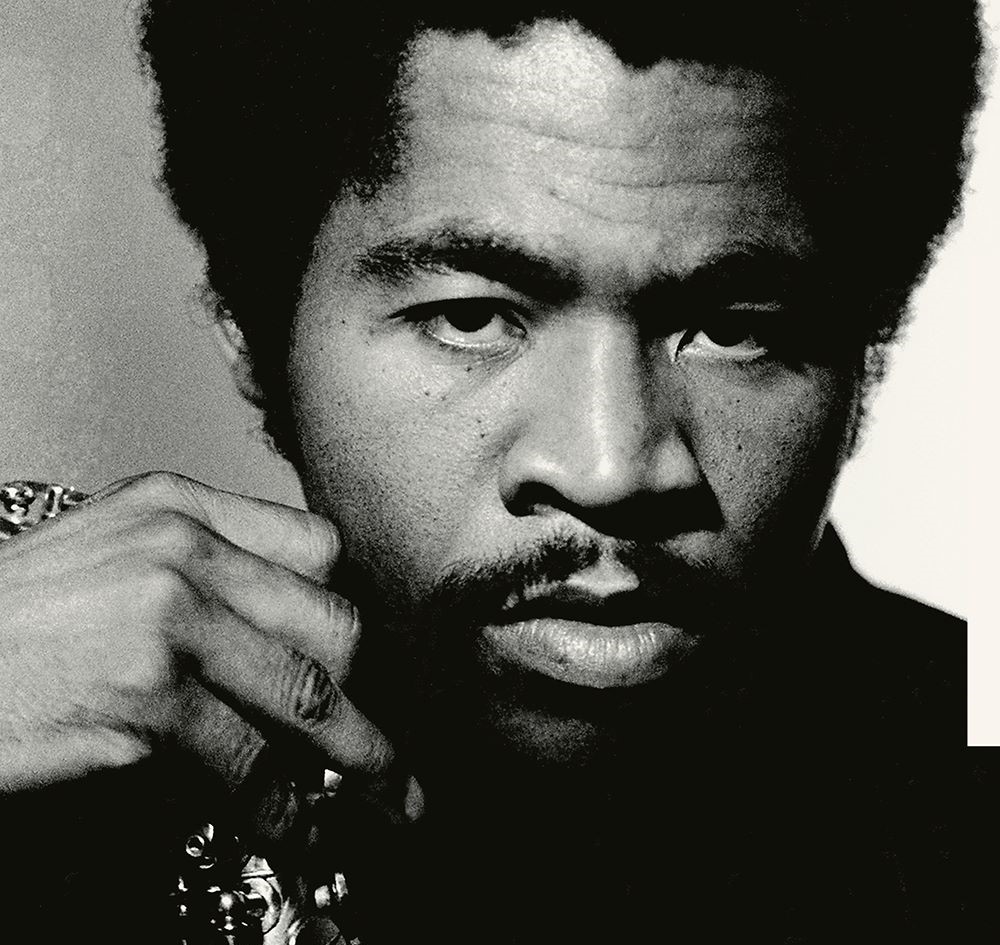

Byard Lancaster: The Sacred, the Profane, and the Palm Years | Unearthing Lancaster’s Palm Recordings

Byard Lancaster was a shape-shifter, a saxophonist and flutist whose work oscillated between the sacred and the profane, the structured and the chaotic. His Palm Records era, now meticulously compiled in ‘Byard Lancaster – The Complete Palm Recordings 1973-1974’ (Souffle Continu), represents a key chapter in his relentless pursuit of a sound both ancient and futuristic.

Souffle Continu’s new release does more than collect four of Lancaster’s essential albums—’Us,’ ‘Mother Africa,’ ‘Exactement,’ and ‘Funny Funky Rib Crib’—it provides a rare standalone edition of ‘Love Always,’ an expansive modal piece, and contextualizes his Parisian years in a 20-page booklet written by Pierre Crépon.

Byard Lancaster remains a spectral presence in the corridors of avant-garde jazz, a mercurial force who operated on the fringes of both form and tradition. A sprawling 5LP+12”+7” set, the collection traces the Philadelphia-born saxophonist and flutist’s Parisian sojourn under the auspices of Jef Gilson’s Palm imprint. These recordings capture Lancaster at his most restless and unencumbered, charting an arc between the spiritual effusion of Coltrane, the torrential phrasing of Dolphy, and the groove of James Brown.

At the heart of this collection is ‘Love Always,’ an incantatory 15-minute opus where Lancaster’s alto levitates above Gilson’s patient piano voicings. This is not mere documentation but a dispatch from an artist whose reach forever exceeded his grasp.

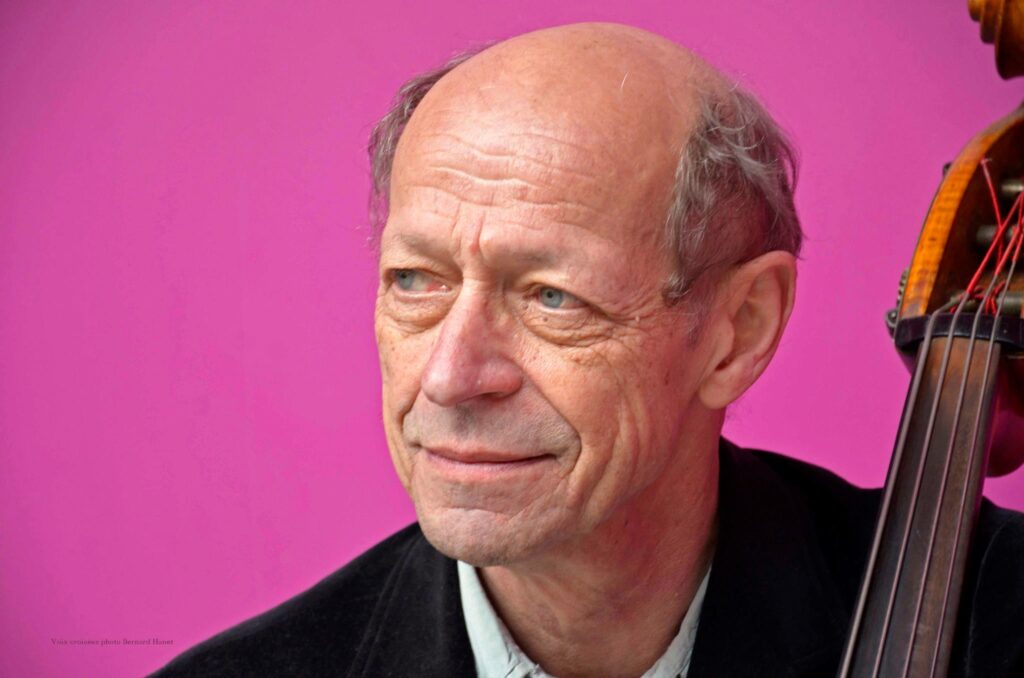

Pierre Crépon, who authored the liner notes, and Didier Levallet, a collaborator of Lancaster, provide insight into the creation of this release.

“A mix between taking care of melody and letting freedom roll”

What was your approach to structuring the narrative for the liner notes?

Pierre Crépon: I focused on what is special about the box set, the fact that it is a collection of actual albums—not salvaged tapes—made over a very short period. There are few parallels for this; it was still early in the 1970s for small independent labels, and market research certainly would not have suggested producing that many Byard Lancaster albums. This led me to think that the story should not be strictly about Byard, but rather be both about Byard and the producer of those albums, Jef Gilson. Gilson was an interesting musician himself; he was significantly older and came up before free jazz. I focused on how this encounter led to the creation of albums that would not have existed had it not happened.

The level of detail in the notes is remarkable. How did you approach your research for this project?

Crépon: I always approach research the same way. First, I try to gather everything that’s out there in terms of sources and tapes, from all instances of a musician discussing his life in general to local one-liners announcing gigs for the period I’m researching. Then, I break the material down into parts that can be arranged chronologically or thematically. The story often starts to emerge at this point. You see what was important to the person you’re writing about, what seemed important to others. Reconstructing a chronology, you think about what happened, but you also get to think about what did not happen. The gaps and tensions often provide good angles to start writing something that’s hopefully grounded in the sources and is not simply an opinion on the music.

How did you decide which aspects of Lancaster’s life and work to emphasize, given the limited space in a booklet? Were there areas you had to reluctantly leave out?

Crépon: Personally, I prefer liner notes that are tightly focused on the music they accompany and the moment during which it was made. The temptation to cover a musician’s full biography might be there, but there’s always the risk of doing something that’s too generic. There would be a lot more to say about Byard’s 1960s work, his New York period, the attempts at getting community-based ventures going in Philadelphia, the later evolutions of his sound, etc., but I think his time in Paris allows one to outline important things about who he was as a musician throughout his life.

Lancaster often emphasized the importance of Philadelphia in shaping his sound. How do you see his Philadelphia roots manifesting in his recordings, especially during his time with PALM?

Crépon: I don’t have a definitive answer to this question, but there’s one point I would venture. Maybe the Philadelphia identity was more something Byard tried to manifest than something he really managed to establish. As has been rightly pointed out, tons of jazz musicians of prime importance to the 1960s came out of Philadelphia: three-fourths of the John Coltrane Quartet should be enough, but there were also Lee Morgan, Sunny Murray, Archie Shepp, Henry Grimes, Rashied Ali and his brother Muhammad Ali, etc. But since their importance is to the overall development of jazz, they’re generally thought of simply as New York musicians. It’s also not shocking to think of Byard as someone who came out of the original New York free jazz scene. Listening to Byard with the Sounds of Liberation group, for instance, it seems clear what kind of identity he might have wanted to establish for the Philly scene, with the mix of jazz and R & B elements. But it’s also interesting to think about what did become identified as the “Philly sound” in the 1970s: the great soul that was being issued by Philadelphia International Records. In terms of R & B, Byard’s thing was clearly James Brown, and as far as I know he didn’t try to jump on the Philadelphia International bandwagon when it got going. This is kind of interesting to me, but people better versed in the local history would probably have better observations to make.

The partnership between Lancaster and Gilson brought together two distinct creative minds. Their dynamic during the PALM recordings reveals much about their mutual respect and artistic approaches.

Crépon: The main thing is really that these albums exist at all. Secondly, my impression is that Gilson knew that Byard Lancaster was the person who knew best what Byard Lancaster should be playing, and that Byard in return respected Gilson’s craftsmanship and ability to make quality finished products. Gilson didn’t throw his aesthetic options in the face of listeners, but they are definitely there through Byard’s albums and through the whole PALM catalog, in the way he recorded, mixed, edited, and used multitracking. If you listen closely to the box set, you hear that Gilson adapted to the circumstances of each individual project; he didn’t just apply a rigid playbook. This adds a very interesting layer to the music.

“Byard came out of the “New York school” of free jazz.”

Lancaster’s story is intertwined with figures like Sunny Murray and movements like the loft scene in New York. How does his narrative expand our understanding of the avant-garde jazz diaspora in the 1970s?

Crépon: As touched upon earlier, Byard came out of the “New York school” of free jazz. For me, there was a breaking point for this scene in the early 1970s. This tends to be obscured by the idea of automatic continuity with the loft scene of the 1970s, but I believe close observation shows that its dynamic came to a halt and that a fragmentation of the music ensued. I would say that Byard’s story illustrates this aspect quite well.

Lancaster’s unaccompanied solo work on Exactement was groundbreaking for its time. What sets it apart from Anthony Braxton or Steve Lacy?

Crépon: In Philadelphia, there was a great avant-garde saxophonist few people know about named Jimmy Stewart. He was also a very good writer, and one of his pieces, published in The Grackle journal in 1979, deals with unaccompanied playing. Stewart makes an interesting point, writing about a Braxton album: what makes a solo piece truly solo? When is a musician improvising completely freely, and when is a musician playing to the accompaniment of phantom colleagues only he can hear? I’ll leave the final word as to what’s happening where to musicologists, but I think this is an interesting question.

Byard Lancaster’s integration into the French jazz scene of the 1970s coincided with a broader embrace of avant-garde jazz in Europe. How do you see his collaborations with Jef Gilson and others as shaping, or being shaped by, the evolving European jazz idiom?

Didier Levallet: I would not say that it has been a broad interaction between Byard Lancaster and the French avant-garde jazz scene. He came and played as a soloist in clubs and different venues. I used to play with him – but now I don’t remember who the other musicians were. In fact, the influence of American so-called “free jazz” on the French ones was some years earlier: 1969, after the Algiers festival (July), when people like Archie Shepp, Clifford Thornton, Sunny Murray, etc. went to Paris in August after Algiers, and then the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Anthony Braxton, etc. This was when the Actuel/Byg series of recordings took place. So the French musicians involved in the “new thing” were in contact with it from 1969/70 (and in some cases sensitive to the “European improvised music”).

Byard went later and was just an individual. Gilson’s PALM Label began in 1972.

Gilson’s work with Malagasy musicians added a distinct flavor to the PALM catalog. How do you think Byard Lancaster’s contributions, particularly his free-form improvisational approach, interacted with these unique rhythms and textures?

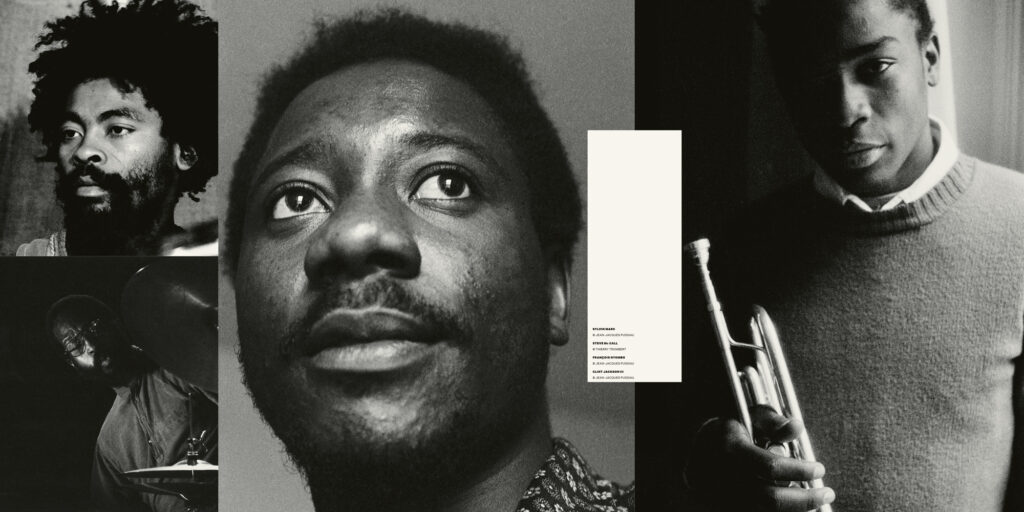

Levallet: To my knowledge, the only junction between Byard and Madagascar is in the record ‘Us,’ featuring the bass player Sylvain Marc, which indeed brings an African feeling.

Lancaster’s willingness to bridge avant-garde jazz with more accessible grooves and even R&B was unusual among his contemporaries. How do you interpret this duality in his artistry, and did it present challenges or opportunities during his time in France?

Levallet: Byard used to play some standards (like ‘Over the Rainbow’) and composed some simple melodies, as parts of his current répertoire. But he used to play (in France) in a context of quite avant-garde audiences. So it was a mix. I knew he was caught by James Brown.

From your perspective, what lasting impact has the label, and specifically Lancaster’s work on it, had on jazz historiography and independent music production in France?

Levallet: PALM is, among other independent labels, one that flourished in the ’70s (first of all: Gérard Terronès’ Futura in 1969, then Owl Records in 1975, Musica Records in 1977). The difference is that Jef Gilson had the recording studio. There was a time when some audiences (not very big, but still) followed these productions. I’m not sure that today so much is left.

Reflecting on your early collaborations with Byard Lancaster, what stands out most about his approach to ensemble dynamics, particularly in settings that combined traditional jazz with avant-garde and free improvisation?

Levallet: Sorry, but this is very old… I can just repeat that he made a mix between taking care of melody and letting freedom roll.

‘The Chat qui Pêche’ sessions seem to highlight a particular synergy between you, Siegfried Kessler, and Lancaster. Could you delve into how the physicality and acoustics of that venue shaped your interactions during those performances?

Levallet: ‘Le Chat qui Pêche’ was a kind of archetypal modern/avant-garde jazz club. I used to play there in different settings, with a wide range of soloists—from Hal Singer to Slide Hampton, Steve Potts, Ted Curson… At those times, the classical setting of a cellar with very few sound systems prevailed. I teamed with Siegfried in our free jazz group “Perception” (1970–77) and as a rhythm section with several American soloists as well as in a duet. So we were close to each other.

Byard Lancaster’s panoramic outlook on music often involved a fusion of genres, from bebop to R&B. As a bassist, how did you navigate the transitions between these stylistic realms while maintaining a cohesive sound?

Levallet: As a jazz lover and musician, I listened to the entire historical scope of the music, so I was supposed to be able to play bebop as well as free music. The Byard approach was just to play the feeling of “tradition” into a free approach.

Didier, you started as a self-taught bassist. Can you tell us about the early days of your musical development? What drove you to pick up the double bass, and how did you navigate your learning process without formal instruction?

Levallet: I used to play guitar as a self-taught musician at 14. Then I used to play the alto sax at 17. Around 20, I took up the bass, but finally I entered the Conservatoire de musique de Lille (in the north of France), where I lived and was a student (at the École de Journalisme) to practice the bass – and forgot the saxophone.

Throughout your career, you’ve played alongside legends like Johnny Griffin, Archie Shepp, and Mal Waldron. What were the most formative experiences or lessons you learned from collaborating with such iconic musicians in your early years?

Levallet: Shepp and Griffin were just single dates, but with Mal, I played a while at the Gills club and that was very formative. Anyway, I was just living “a dream come true”…

Your work as a composer and arranger has earned significant recognition. How would you describe your approach to composition? Is there a particular philosophy or concept behind your music that you continually return to in your writing?

Levallet: If my writing succeeded in some way, it’s mainly the outcome of my love for the music I’ve listened to over and over since I was 12—from Sidney Bechet to Albert Ayler and beyond. I never had any formal education, just one or two pieces of oral counselling from a friend. So it’s always a new story and a new adventure. I try to be faithful to what moves me in that music from the beginning. Not to forget the song – and the freedom.

You were at the helm of the French National Jazz Orchestra between 1997 and 2000. What was that experience like, leading such an influential ensemble?

Levallet: First of all, it was about having a regular group of very good musicians to work with consistently—and we did a lot of concerts, in France and all over Europe. And the symbol was important: the French state gives official consideration to this music.

Looking back on your career, are there specific recordings that you hold in particularly high regard, either as a bandleader or a sideman? What makes these recordings so meaningful to you?

Levallet: The first record of ‘Perception’ (1971) had something very strong in its free feeling. I think my three records with strings (Swing Strings System: 1978, 1988, 1989) succeeded in an unexpected register. And I like my last one with the quintet ‘Voix croisées’ (2013).

Over the years, you’ve performed at numerous venues and festivals. Which gigs have had the most profound impact on you, whether from a personal or musical perspective?

Levallet: Well, I have organized, since 1977, a workshop and a festival in a small medieval city in the south of Burgundy: Cluny. In some way, I can be proud of it.

As an educator, you’ve shared your knowledge with aspiring musicians. What key elements do you emphasize in your teaching, particularly to students learning the intricacies of jazz bass and improvisation?

Levallet: I never taught specifically “jazz bass,” but “jazz playing” for all instruments. Well, it’s not so easy to sum up, but: learn some rules and… “speak, brother, speak!” Avoid a too academic attitude.

Finally, if you were to describe the essence of your playing in just a few words, what would they be? What do you hope to convey through your bass playing every time you perform?

Levallet: Not easy… If words could tell… why play? Emotion and inner song.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Gérard Rouy

Souffle Continu Records Official Website / Facebook / Twitter / Bandcamp