Dulcimer | Interview | “And I Turned As I Had Turned As A Boy…”

Dulcimer is a relic of the progressive-folk underground that still sends shivers down my spine.

Their story begins in a Cotswold restaurant, where an unexpected performance caught the eye of Richard Todd, setting in motion a whirlwind that led them to the legendary Larry Page and his Nepentha label. Their debut, recorded live in one marathon session at Lansdowne Studio, crackled with spontaneity and a fragile beauty that captured the essence of a simpler and definitely more honest time.

Their sound is a mosaic of rustic simplicity and wistful melody, drawing from English tradition and evoking vivid memories of childhood, countryside reveries, and secret fantasy worlds. With an eclectic arsenal of instruments—from twelve-string guitars to dulcimers and banjos—Dulcimer crafted songs that were both haunting and uplifting. Their music, steeped in English tradition and imbued with poetic lyricism, won critical acclaim, earning nods from Melody Maker and a loyal following from Japan to Austria.

Though the band’s later chapters were marked by more albums and sporadic reunions, their music remains genuine and unpretentious. And without further ado, Dulcimer is nothing short of a hidden treasure.

“Incredibly, we recorded it all in one session, entirely live, and many of the songs in one take.”

It’s a pleasure to have you with us. How are you, and what’s been keeping you busy these days?

Pete Hodge: Well, Klemen, as befits a person of my vintage, I have had a few health issues over the past year or so. The downside is that it’s very inconvenient and energy-sapping, but on the upside, it’s brought home to me the importance of doing things that bring joy and fulfillment—in my case, writing and recording songs and producing albums, which I continue to do with great enthusiasm.

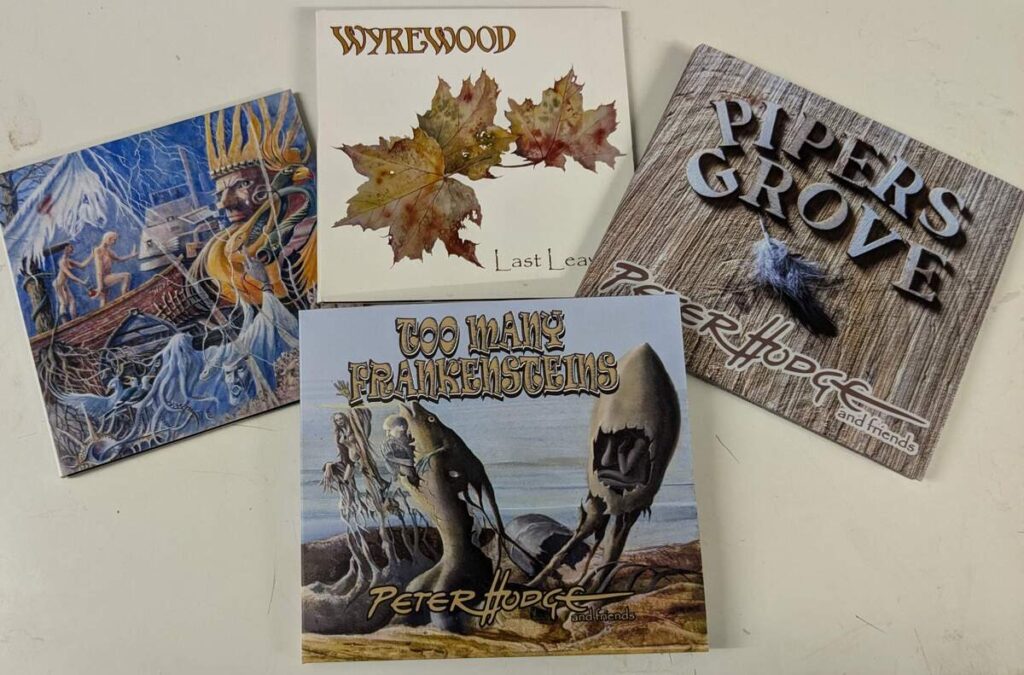

You’re still a very active musician with a few solo releases under your belt, the latest being ‘Pipers Grove.’ Could you share some words about the inspiration behind your latest album?

Actually, I now think of ‘Pipers Grove’ as my “previous” album, as I have just completed a new one called ‘Too Many Frankensteins,’ which I hope to launch, in some small way, before Christmas.

However, to answer your question, ‘Pipers Grove’ could loosely be described as a concept album—”a bit arty” and self-indulgent; a journey through life, partly from my own remembrances (including my time with Dulcimer on the track ‘Three Winters’), but also through the eyes of a group of strange and disparate fictional characters. I enjoyed the whole process and was very happy with the result.

I feel my new album is less esoteric and a little more accessible—still a little lyrically weird and more “folk rockish,” with a few meditations on life, a bit of “nostalgesia,” and a few thoughts on today’s obsession with celebrity over talent, with Andy Warhol’s prediction that the future would see everyone being famous for fifteen minutes finally reaching fruition.

Your previous release, ‘Forgot Your Password? – Try Again,’ seems to have been created during the pandemic. How does that record compare thematically or musically to ‘Pipers Grove’?

I’d been in a little band called Wyrewood for a couple of years, working with Rob Powell, a very talented musician/singer/songwriter, and Lorna Joy Davies, a fine cellist and flautist. We had just completed our second album—all originals—which we recorded in Lorna’s home studio on top of the Malvern Hills and had also done a few concerts when COVID struck. I was well into writing songs for the next album, but it soon became apparent that it was not logistically feasible to continue as before. Also, Rob and Lorna had other projects on the go. That’s when I got in touch with Tim Haines, an old friend, musician, and producer, with thoughts of trying out a few of these new songs in his recording studio.

That was the genesis of ‘Forgot Your Password?,’ and although we started slowly, soon the songs were flowing, and eventually, Rob and Lorna found time to help me out. So although it was my “solo” album, Rob, in particular, brought some classy backing vocals and keyboard skills, while Lorna added some deft flute and cello to the proceedings, and Tim provided percussion and bass.

Most of my songs have been stories set to music, sometimes from personal experience but more often dragged from the mysterious world of imagination, and these ten tracks were no exception.

All in all, this album got me really hooked on recording again, and although it was recorded during COVID, there are no direct references to it—although the last track, ‘Let’s Re-invent the Wheel,’ does touch on it, but more as a reflection on what was, for me at least, a time of quiet optimism. A short period when we weren’t engulfed in traffic, the skies seemed bluer, rivers ran bright and clear, and people learned how to respect each other and even talked to each other—perhaps optimism is a bit overrated. A pessimist is never disappointed!

Before we explore your time with Dulcimer, I’d love to hear about your involvement with Bang Bang Machine and the ‘Evil Circus’ EP. What can you tell us about that project?

This was a very brief involvement. At the time, I had a day job as an artist/designer, and I still did until recently. As BBM were locally based, they seemed to know of my strange, fantasy paintings and approached me with a view to producing artwork for their forthcoming album ‘Evil Circus.’

I was a bit snowed under at the time, but having listened to the album, I showed them a painting I had already done, which seemed to capture the mood. They liked it and used it.

They were a fine, inventive band led by Steve Eagles, with lots of talent and interesting themes. I must make a point of listening to that album again.

As a footnote, I have used part of the same painting on the inner sleeve of my latest album, as it seemed to capture the essence of a track called ‘Masque.’

Let’s step back to your early days. Where did you grow up, and how would you describe your upbringing?

I grew up in the small village of Snowshill, high in the Cotswold Hills. It was a simple, uncluttered upbringing and mostly happy, although even from an early age, I was aware of an underlying melancholy, perhaps because there were few children of my age in the immediate vicinity—my sister and her friends were some years older than me.

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, we were fairly poor, my parents mostly living off the land and “making do.” Often, my father would bring home a pigeon, pheasant, or even an occasional squirrel for the dinner table. It wasn’t until I entered my mid-teens and was studying Wordsworth and the Romantic poets at school that I began to understand the majestic yet brooding magnificence of solitude in nature, and I think some of this later seeped into our music.

When did music first captivate you? Could you talk about some of the key influences that initially shaped your musical interests?

This follows on nicely from the previous question, as I think it was art and later music that occupied the many hours I spent in my own company. There were no musicians in my immediate family, although my grandmother did play a few excruciatingly unrecognizable hymns on an old harmonium.

I’m not really sure whether there was a lightbulb moment, but I seem to remember that early pop bands like The Searchers and even Freddy and the Dreamers brought excitement and energy from another dimension, challenging the bland, grey balladeers of the early sixties much beloved by our parents.

It wasn’t until my mid-teens that I stumbled on the first acoustic albums by Dylan and Paul Simon that I realized music was not the sole domain of guys with electric guitars, cool haircuts, and smart suits.

Dylan in particular seemed to open the gates for guitar strummers, wailing harmonica players, and people who sang in their own voices to “give it a go”—and, of course, they also wrote their own material and expressed their own ideas. Indeed, “The Times WERE a Changing,” and for me, meeting Dave Eaves ignited the fuse.

Were you involved in other bands or projects before forming Dulcimer?

I played in a skiffle/folk band with a couple of schoolmates, Tom Campbell and Pete Brown, for a short time. Perhaps “played” is a slight exaggeration, as it took me some time to realize that you had to tune guitars! I believe the band was called The Kelpie.

It was at a time when I was slowly improving my guitar-playing skills that I first met David Eaves. I believe my first memory of Dave was seeing him ride into our village on a Vespa scooter with a 12-string guitar strapped to his back. Dave had moved from Coventry to take up a job as a cabinet maker in nearby Broadway and, although a little younger than me, he had already garnered a degree of musical knowledge and a small reputation as a performer at the folk clubs in that area.

It was not long before we were strumming together, and Dave shared his superior musical skills with me.

At the time, I was attending Gloucestershire College of Art, so most of our musical forays took place on weekends or on weekdays in Cheltenham, in or around The Exmouth Arms Folk Club, where we teamed up with Jill Smith, an accomplished solo performer, under whose tutelage we became the unofficial house band.

It was here that we met many experienced artists, including Decameron, a fine Cheltenham-based folk-rock band who also had a residency in a club called The Cellar Bar. They were a little older and more worldly-wise than us and already had a large following. I think we were a little in awe of them, as they displayed an innate “cool” professionalism and also seemed to attract all the good-looking women! They were also a great band.

We, meanwhile, had saddled ourselves with the name Tommy Porridge—a rather glum, folky, jokey name, the antithesis of “cool”—and no, I don’t know why either!

How did the idea for Dulcimer come about, and when did the band officially form?

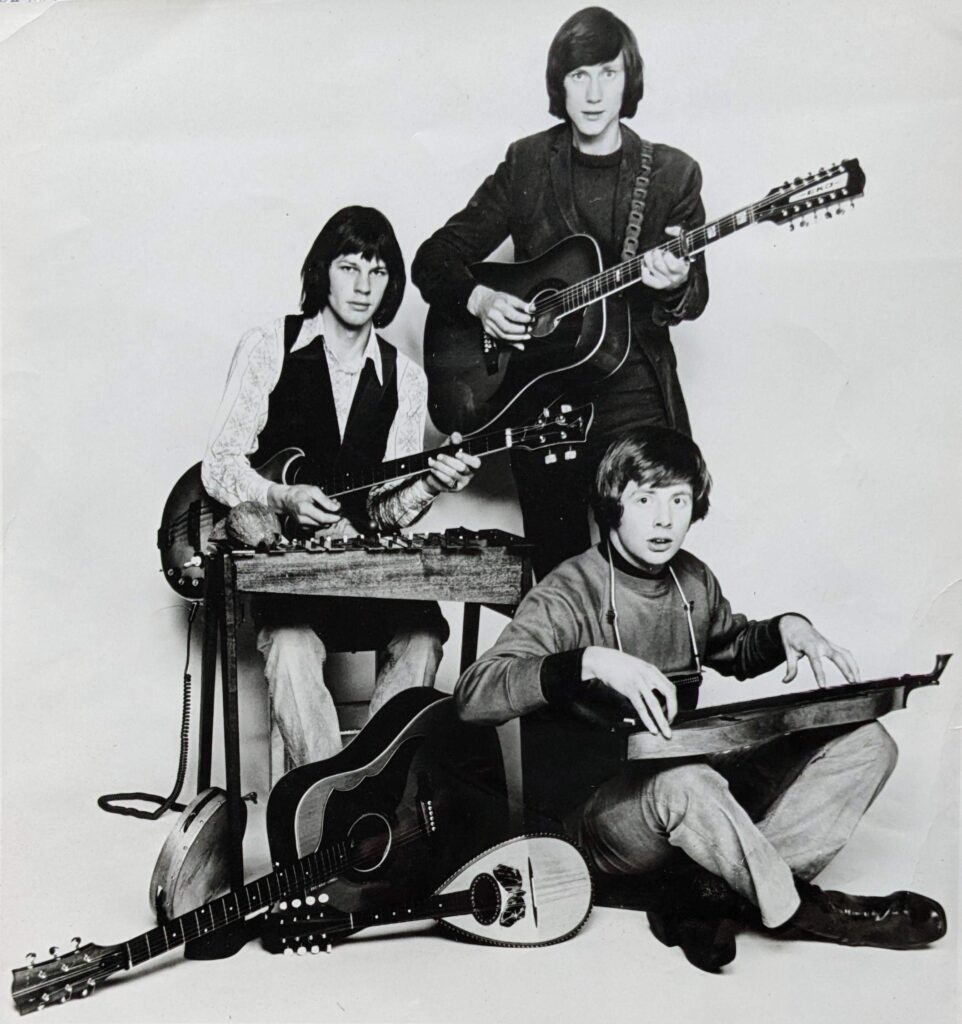

Memory is a fickle friend, but I believe we found our musical measure when we were joined by my cousin, Jem North. Dave had lodgings in the attic of Jem’s house, which also became our practice studio. Jem heard what we were doing and joined us on bass—actually an improvised, tuned-down Spanish guitar. We seemed to gel very quickly, and although he had no previous musical experience, he soon became a fine, inventive bass man. Before long, we were playing in small clubs, pubs, and restaurants—anywhere that would have us—usually acoustically, although Jem eventually started using a small treble amp played at a low volume. We had begun the next phase.

Can you share the story behind the band’s name?

We were named Dulcimer by the actor Richard Todd, who was intrigued by the Appalachian (mountain) dulcimer that I had started playing.

Richard was very “instrumental” in the next phase of our development, having “discovered” Dave and me playing in a small Cotswold restaurant. He introduced us to musical impresario Larry Page, which led to a recording contract and our first album.

What was the music scene like in your area during the ’60s and ’70s? Was there a strong counterculture presence—hippies, beatniks, or otherwise?

I guess there was a counterculture thing going on at the time, but we were more ensconced in our own musical journey. Since our main concert venues were small folk clubs and occasional art venues, we were somewhat on the periphery of the “swinging sixties.”

Of course, I, being an “art school boy,” was a little closer to that scene in dress and outlook, while Jem favored smart Zoot suits and cigarettes, and Dave was somewhat more traditional in attire and attitude. Sartorially, we didn’t really cut it in the brave new world. I think naive and disparate would best describe us at the time.

What did Dulcimer’s early repertoire consist of? Did you perform live often, and who were some of the notable acts you shared the stage with?

Initially, corny folk songs with a few Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel, and Beatles covers thrown in—but Dave and I were soon writing our own songs. It wasn’t planned; it just happened very naturally.

We were fairly limited in where we played at this stage, as we were still performing acoustically in small venues where people actually listened. Besides, we couldn’t afford the PA system needed for bigger venues—even if we could have gotten gigs. Later, our close friend Dave Hazelwood took on “roadie” duties and supplied his own system. We were very grateful to him, but folk clubs remained our main venues, and many clubs still forbade the use of “electrical gimmickry.”

We always felt a little on the outside. It wasn’t until Larry Page became our manager that the game changed.

Could you tell us about the instruments and amplifiers you used in your early years?

Dave and I both played Eko guitars—12 and 6 strings—two of the cheapest guitars on the market. Jem played a mid-range bass through a small Vox guitar amp. We also begged, borrowed, and bought other instruments, including harmonicas, recorder, glockenspiel, Appalachian dulcimer, mandolin, and a box of strings we christened “the Gloucester Chimes.” Later, we added a rather heavy, wheezy harmonium. Some of these were of reasonable quality, while others were found in attics and junk shops—somewhat prone to going out of tune very easily, which was a constant irritation.

When did the band first start playing together, and how long did you remain active?

As a trio, it was probably around 1969, although Dave and I had been playing together for maybe a year before that. The Dulcimer three-piece lasted for about three years, during which time we were living in and “getting our thing together, man” at Narrow Meadow Farm—an old, dilapidated farmhouse outside town. Eventually, Jem left the band to pursue “meaningful employment” as a lorry driver, and although Dave and I continued writing, recording, and occasionally gigging through the ’70s, we eventually abandoned the idea of “making it big time” in the music scene and moved out of the farmhouse. Marriage and raising children became our priorities, but even then, we continued to get together on various musical and artistic endeavors.

Meanwhile, Jem stayed on at Narrow Meadow Farm, which became a “cultural” gathering place for musicians and the scene of wild parties. It was demolished a few years later but still holds a near-legendary status for the hedonists of that era.

Did you have a manager to help navigate the music industry at the time?

When Richard Todd introduced us to Larry Page, they set up a joint management team, with Larry controlling the music/business side of things and Richard acting more as a mentor and father figure.

What’s the wildest or most memorable concert you ever played with Dulcimer?

That’s a difficult one. In terms of “wildest,” it was probably a fairly small club gig we performed somewhere in Wales. As we were considered to be an overly serious, aesthetically sensitive band, we thought we needed to broaden our appeal by introducing a bit more humor into our performances.

Jem, in particular, entered into the spirit of things, and during one of our “funny” songs, he and I engaged in a badly choreographed “spoon fight,” resulting in minor injuries. At that same gig, Jem also started playing a one-stringed fiddle while standing on one leg on a chair, furiously puffing on an old briar pipe. He even found time to float balloons over the audience, which people naturally started bursting. Unbeknownst to us, he had previously filled them with quite large amounts of baking flour—the “fallout” was considerable. Although he repeated the stunt at another gig, we quickly realized it did not add to our popularity. It was a very amateur, folksy Spinal Tap disaster.

I’m not sure about the most memorable gig, but certainly the scariest was playing to an audience of music critics at Ronnie Scott’s in London for the launch of our first album. The biggest was probably supporting Curved Air.

We also played some live TV shows in Amsterdam, Vienna, and Wales—also pretty nerve-jangling.

How did Dulcimer come to be signed by Mercury Records?

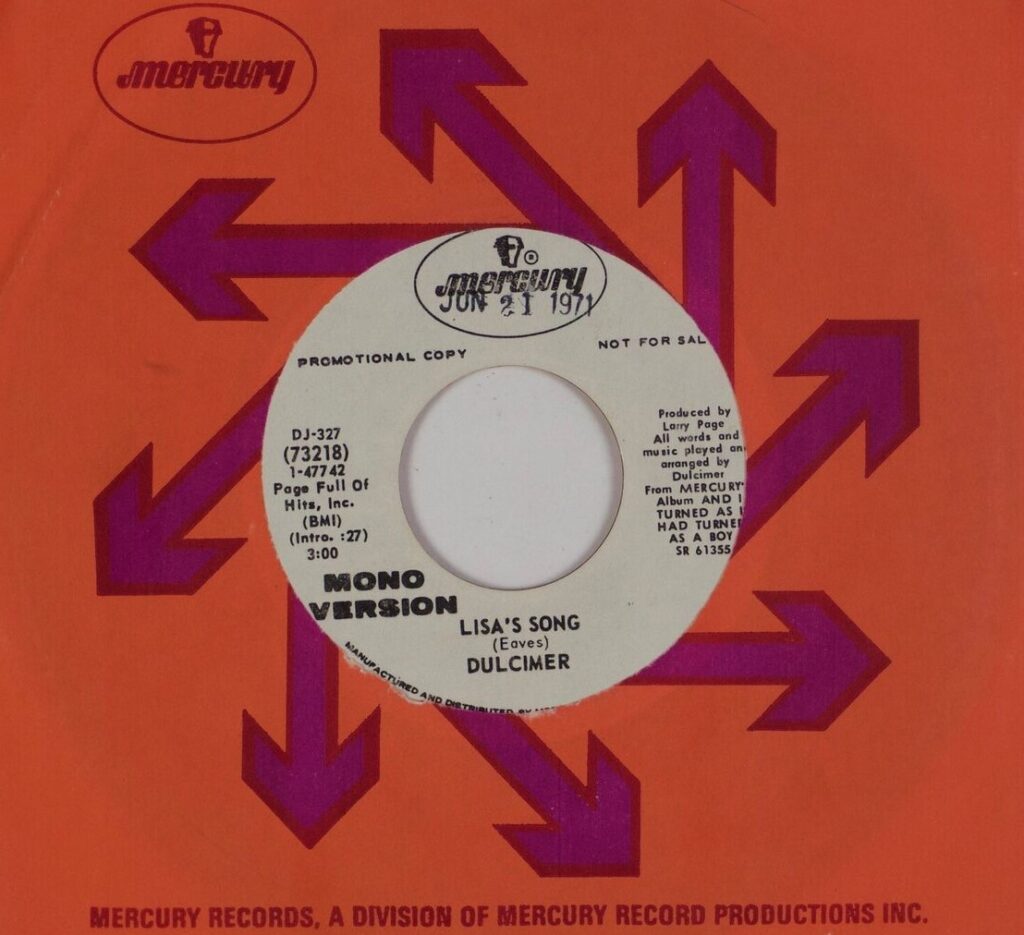

I’ve no idea. I presume it was a deal done by Larry to break us into the American market.

I think we were pretty uninterested in that side of things as, like most young musicians, we just wanted to play and record; enthusiasm and naivety only got us so far! There were a couple of projected tours of America and Japan, but that flight never took off!

Let’s talk about your 1971 album ‘And I Turned As I Had Turned As a Boy.’ What were the circumstances surrounding its creation?

Having been spotted by Richard Todd, a major film star of his day, we were invited to his home to discuss the possibility of us writing some material for him, combining our songs and music with poetic narration by him. It was a no-brainer and a big chance to progress our songwriting skills.

We had the wind in our flares, and within a few weeks, Dave and I had written a group of songs, poetry, and prose to feature Richard’s deep, resonant voice. In the meantime, Richard had contacted Larry Page, who was about to launch Nepentha, a singer/songwriter label. At the time, Larry was managing The Kinks and The Troggs, so we were in good company, and things were gathering pace.

How much time did you spend recording the album, and what was the experience like in the studio?

Incredibly, we recorded it all in one session, entirely live, and many of the songs in one take.

We arrived at Lansdowne Studio, set up our instruments, and engineer David Baker miked us up. We ran through a few songs for what we thought was a sound check, and suddenly Larry Page announced, “It’s a wrap,” and told us to come up to the control desk and have a listen. It was the first time we had really heard ourselves playing, apart from a few distorted cassette recordings, and we were very happy with what we heard—we actually sounded like a real band. I believe that first song was Lisa’s Song, which later became our only single release in the States.

From then on, Larry’s production role consisted of keeping us going with the occasional enquiry: “Have you got anything else, lads?” He had, however, already performed his masterstroke by cleverly “tricking” us into thinking we were just practicing, hence getting us relaxed and confident. I seem to remember there were even another couple of songs not included. Richard came to the session late on, and amazingly, although we had never practiced the two fairly complicated song and narrative arrangements together, we did them both in one take! After the first song, we never got to hear another playback until the album came out.

“Literature obviously played its part, as Dave and I were both avid readers.”

Could you share your thoughts on the songwriting process? What inspired the tracks on the album?

I don’t think we had any parameters, as we just wrote about things that interested us with no thoughts of commerciality or what was current. Works such as ‘Caravan’ and ‘Sonnet to the Fall’ came from our rustic roots, while Dave’s romantic ballads and my surrealistic fantasies were both rooted in the normal angsty, teenage coming-of-age lessons we were learning. Literature obviously played its part, as Dave and I were both avid readers.

I’d love to hear your reflections on each track from the album.

‘Sonnet to the Fall’

Incorrectly attributed to me on the album, but actually written and arranged by Dave. The first song written specifically to feature Richard Todd.

‘Pilgrim From the City’

Another of Dave’s songs, and about the most ‘folk-rocky’ track on the album, with Jem in his element on bass.

‘Morman’s Casket’

An inventive fairytale by Dave, probably a little influenced by Tolkien. Jem played bass and glockenspiel, as well as supplying wind and clip-clop horse effects on miked-up coconut shells. Dave played 12-string, and I played mandolin and harmonica. It always seemed quite cinematic to me.

‘Ghost of the Wandering Minstrel Boy’

One of my weird, surrealist cautionary tales that came from who knows where, and the only time Jem sang—just a few notes on the chorus. One of the few tracks where I sang lead vocal.

‘Gloucester City’

One of my songs, based on my time living in Gloucester, where I frequently encountered an old tramp on my daily walk to college. He also featured in the second album on a track called ‘Mr. Rip Van Winkle.’ It was a melancholy time for me, in a city that had its heart ripped out by the ‘modernizers’ in the ’60s. Unusually, Dave played harmonica, Jem played glockenspiel, while I played six-string and harmonized with Dave.

‘Starlight’

A beautiful romantic fantasy by Dave at his vocal best. He later told me it had been inspired by MacArthur Park. Who knows!

‘Caravan’

The track that I was most proud of. Dave and I wrote this together, specifically to feature Richard. Partly based on Dave’s recollections of the Romany caravans of his youth and also by our friendship with a “new age” couple who roamed Britain in the same traditional, brightly painted, horse-drawn vehicle. We spent many an evening around their campfire telling stories and playing our guitars.

As I mentioned earlier, it was done in one take with no overdubs and involved Jem swapping between glockenspiel and bass, and me between dulcimer, mandolin, and harmonica. Meanwhile, Dave held it all together on the twelve-string and directed Richard on when to come in, as we had never practiced the narrative and the music together.

‘Lisa’s Song’

Dave’s emotional song about a lost love. He was on twelve-string and lead vocal, Jem on bass, and me on lead guitar and backing vocal. The single in the States.

‘Time in My Life’

I believe this was the first song we wrote together and probably the closest we came to a hit, as evidently, it did very well in Japan.

‘Fruit of the Musical Tree’

A little too whimsical for my taste and somewhat under-rehearsed and rough around the edges. We wrote this together. I played the eponymous dulcimer, Dave played guitar and recorder, while Jem tapped his bass strings to simulate tablas, and I strum/tapped the strings of the dulcimer with a biro. It gave it just a hint of Indian raga.

‘While It Lasted’

Dave at his vocal best, lamenting the loss of the same American girlfriend. Dave had only just written this, and we were under-rehearsed, as you can hear from some somewhat wobbly mandolin from me. Still one of the best songs on the album.

‘Suzanne’

Co-written by Dave and me and inspired by a girl I worshipped from afar.

Was there a unifying concept behind the album?

Not really, we just wrote about things that interested us. Larry did the sequencing.

What can you tell us about the cover artwork?

I was once more erroneously credited with having designed it, but it was, in fact, the work of Linda Glover—and what a great job she did for us.

I did submit a rather unsophisticated pen-and-ink design, but fortunately, it was turned down, and Linda was brought in to produce this beautiful rustic fantasy image. However, we did negotiate over the number of gnomes and fairies permitted—another Spinal Tap moment!

The single ‘Lisa’s Song’ / ‘Fruit of the Musical Tree’ was also released. Did it receive any airplay or attention in the press?

I don’t really know, but I heard through the grapevine that it got played on the American college circuit. Of course, this was all pre-internet, and there were few ways to follow what was going on—we were somewhat kept in the dark. In fact, in later years, it was often Dulcimer fans who kept us up to date. One in particular, a guy called Garrit Lansink, was very instrumental in the band reforming when he contacted me to tell me about the release—twenty years too late—of our second album.

As I remember it, the letter was addressed to Dulcimer, the Post Office, England, and somehow it got to me—true fame at last!

We kept in touch for many years, as I still do with a German writer friend, Jürgen Gallitz-Ducker, who contacted me concerning some internet misinformation regarding our never fully released ‘A Land Fit for Heroes’ album with Fred Archer. Music definitely brings kindred spirits together. It’s great to keep in touch with these supportive, music-loving friends.

What was the band’s trajectory following the release of the album?

We were forever on tenterhooks, waiting for the next development. Although the album was critically well received and sold a reasonable number of copies (we never knew the figures), and although we had soon recorded a follow-up album, this ‘difficult second album’ didn’t see the light of day until 20 years later, when it appeared as a bootleg album on the internet.

We were never told why it was not released at the time, and gradually, the initial good vibrations ebbed away.

I seem to remember talking to Larry a couple of years after the first album’s release when he was considering reworking and re-mixing the second album, but the band agreed that it was water under the bridge and time to move on. We had also decided we wanted to be released from our contract.

Over the years, Dulcimer has released several other albums, including ‘A Land Fit for Heroes,’ ‘Room for Thought,’ ‘When a Child …,’ ‘Rob’s Garden,’ and ‘Into the Light.’ Could you share some insights into these releases?

‘A Land Fit for Heroes’ was another eccentric project from the mid-seventies, where Dave and I teamed up with author Fred Archer to add songs and musical interest to Fred’s spoken-word take on life after and between the two Great Wars. A curiosity that was not released until some years later. This seemed to happen to us a lot!

It was recorded in Muff Murfin’s Old Smithy Studio in Worcestershire, where he gave Dave and me the freedom to do our own thing. We also acted as a studio songwriting team for him. It was engineered by Colin Bell.

‘Room for Thought’ was our follow-up to our first album—the one that mysteriously disappeared for 20 years. I still feel there were some great songs on it, but there was something slightly lacking in the recording. Unfortunately, Richard Todd was not available for the recording session, and Jem gallantly stepped up to fill the void with a deliberately rustic spoken passage. Possibly not our finest moment.

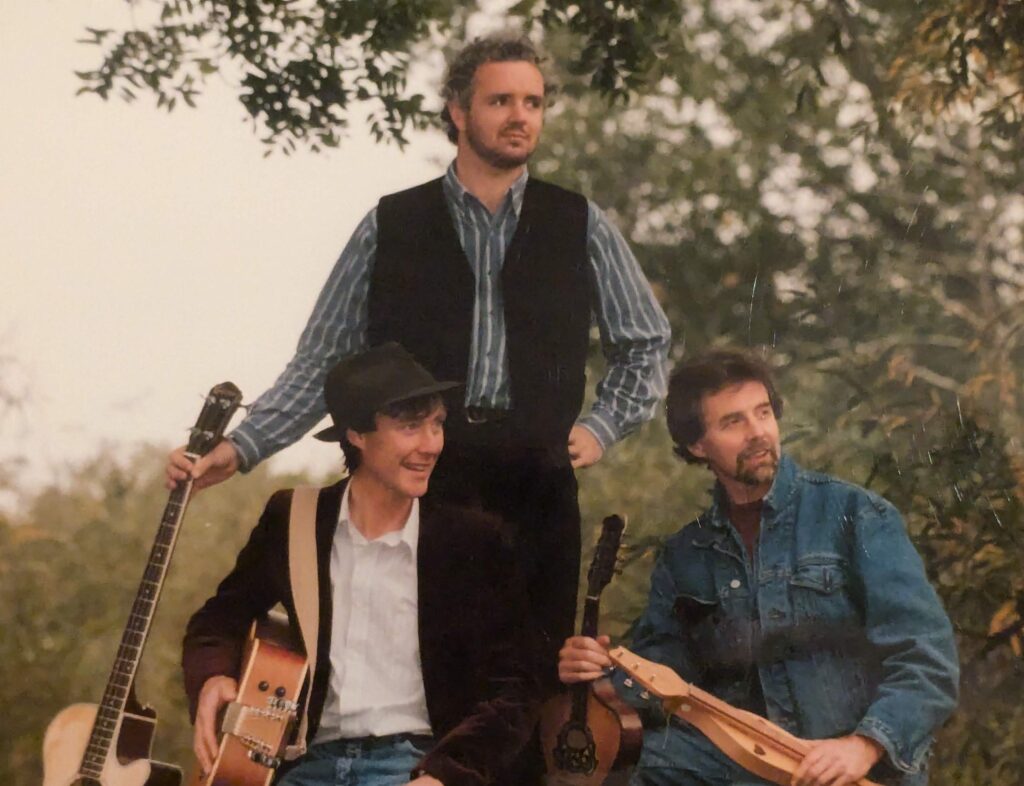

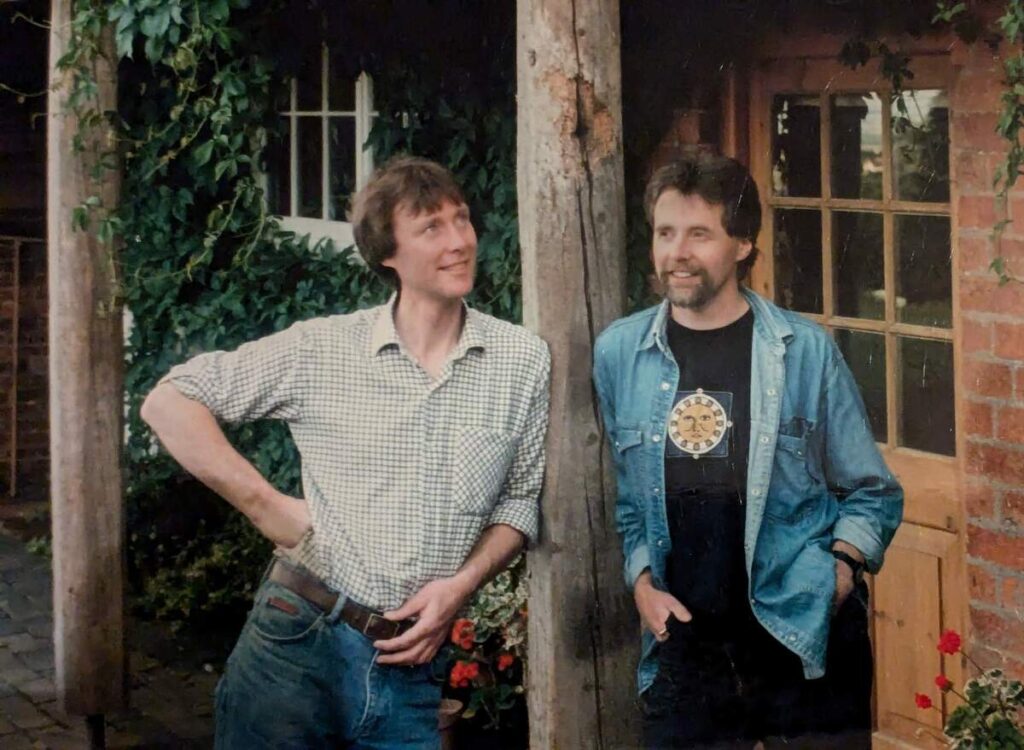

We were ‘rediscovered’ in the early ’90s. Dave and I had been seeing less of each other due to work and geographical reasons, and I had started doing a solo album with my cousin Rob Savage, who had a small home studio in Droitwich. When one of our few remaining fans in Amsterdam informed us that the bootleg album had been released, Rob did a bit of sleuth work and discovered there was still a following for our earlier work.

I can’t remember the exact circumstances, but I do remember Rob, Dave, and I (Jem had moved on by then) traveling down to London and coming home with a three-album deal with President Records. I think they already held the rights to our debut album.

We wrote new material as well as renovating one or two older tracks, and we also brought in multi-instrumentalist Mike Hooper and vocalist Andrea Blyth to enhance and revitalize our recordings. Although we did some promotional work, including a few concerts and live interviews on local radio stations, sales were not great, and we couldn’t really sustain the “second chance” impetus. Once again, things drifted.

It was a good, happy time, and it was interesting to be playing with other musicians. Jem had left quite a big gap to be filled.

Did you or the band experiment with any psychoactive substances, like LSD, during the creation of the music?

Sorry to disappoint, but no, we didn’t—which is strange, as most of the people within our immediate vicinity did.

It was no big statement; we just never felt the need. I did briefly indulge in later years but chose to pursue enlightenment, peace of mind, and creativity through meditation and the exploration of other spiritual practices—and I’m still practicing! It ain’t easy!

I believe Jem may have imbibed a few mind-enhancing concoctions and local cider in later years, as he got very much into clubbing and the rave scene, but Dave never did.

Were there plans to record more material back in the day? Is there any unreleased music or songs that were written but never recorded?

To a degree, Dave and I never stopped. There were several tracks from the first two albums that are probably gathering dust and cobwebs on the shelves of “never to be,” and after that, we embarked on a number of slightly more commercial ventures at the Old Smithy. On occasion, Dave and I persuaded our wives to sing backing vocals. I never felt particularly happy with these projects and did not entertain hopes of us being the next ABBA!

Dave and I also wrote and recorded a musical based on the life of Anne Frank, which was somewhat doomed from the outset, as the idea of a family in hiding suddenly bursting into song at every opportunity was somewhat preposterous. We did, however, use one or two of the songs in later projects, and even today, I have it in mind to revisit a couple of songs for my next album, as I thought they were good songs in the wrong setting.

Did any of the band members go on to join other groups later in the ’70s?

Although Dave and I carried on as a duo, Jem went into slightly more punkish things, and I believe he played bass in a way-out band whose name I can’t remember. As sensitive and subtle as he was with us, I think he craved playing in heavier bands where he could crank up the volume. Who can blame him?

What have you been up to since Dulcimer’s active years?

After Dave and I split sometime in the ’80s, I continued with my day job as an artist but never stopped writing and, whenever possible, recording—including a solo album with Rob Savage in his Ghosts and Nightingales studio. Some of this material resurfaced on the three albums we recorded for President Records.

In the early twenty-first century, I became rather disillusioned with the music industry after being threatened with litigation for allowing our debut album to be re-released in South Korea. It was a totally innocent misunderstanding, as I assumed that Dulcimer had the right to do this. Evidently, we did not, and Larry Page was not a happy man, while I was a worried man.

It was eventually amicably resolved, but for a time, it sapped my enthusiasm for musical creativity.

It was not until 2015 that I got enthused again after a chance meeting with musician Rob Powell at a local music pub, where we strummed guitars together in the early hours of the morning, long after the main acts had packed up and gone home. We quickly gelled and soon recruited Lorna Joy Davies to play cello and flute with us. They were both fine musicians, and writing and playing with Rob was very similar to the way Dave and I worked together. As I mentioned earlier, we produced two albums and performed a few concerts as the band Wyrewood before COVID stopped us in our tracks

However, the creative seed was growing again, and in the last five years, I have been more productive than ever and have produced three solo albums of what I believe is my best work so far.

Have you kept in touch with the other members over the years?

Sadly, Dave and Jem departed this planet some years back, and this is particularly sad and poignant to me, as I am unable to check out and reminisce with them on this questionnaire. I know they would both have been delighted to know that there is still a little residual interest out there for the brief period of creativity we shared together back in the last century.

Fortunately, we did all meet up a few times in later years, and I spent valuable time with both of them shortly before their deaths.

Looking back, what stands out as the highlight of your time in the band? Are there particular songs or performances you feel most proud of?

Probably writing and recording our first album. It was quite an achievement for three country bumpkins to have produced a little bit of musical magic that survives and still garners a little interest to this day.

Personally, I’m equally proud of the albums I’ve produced and been involved with in the last few years—I do visit the past from time to time, but I don’t dwell there and am always looking to improve with the next song or album. It’s a constant challenge and joy.

What are some of your favorite memories from your time with Dulcimer and the ’60s/’70s in general?

I think I’ve probably covered that already, but it strikes me that the past can become greatly colored and enhanced by the passage of time. My main memory of those years would be the excitement of the world we crashed into and the simple, unhampered creative force that drove us forward.

Who were the most influential musicians for you personally, and what elements of their style did you admire or adopt?

From that period: Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, Joni Mitchell, and Leonard Cohen—all the American/Canadian big-hitter singer-songwriters. And from this side of the pond: Richard Thompson, The Incredible String Band, and a little later, Mike Scott and 10cc, who, to me, were as influential as The Beatles.

In recent times, I have become a little disillusioned by the artificial, bland, and repetitive music of the moment—until my son got me watching live videos by the Welsh genius Ren; in my opinion, the greatest artist of my generation.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

First, an apology—I didn’t expect as many questions and certainly didn’t intend to write so much, but once the floodgates of memory are opened up, it’s amazing what pours forth. I could have written more!

It’s been a cathartic experience, and sad that I can’t share this with Dave, Jem, and Richard Todd. I have recently heard that Larry Page also passed away this year. So, I guess that makes me the sole survivor!

So, I think I have earned the right to shamelessly plug my recent albums, particularly my latest: Too Many Frankensteins. They are all available on Bandcamp and through my website: petehodgemusic.co.uk.

I swear on this mobile phone that I have told the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth—but accounts may slightly differ!

Finally, a thank you to the friends who have continued to support me and my music through the years—especially Chris, Diane and Caleb Jennings, Rob Powell, Karen Osborne, and Keith Bolton.

Thank you for indulging me in this journey through the magic mirror of time and memory.

Klemen Breznikar

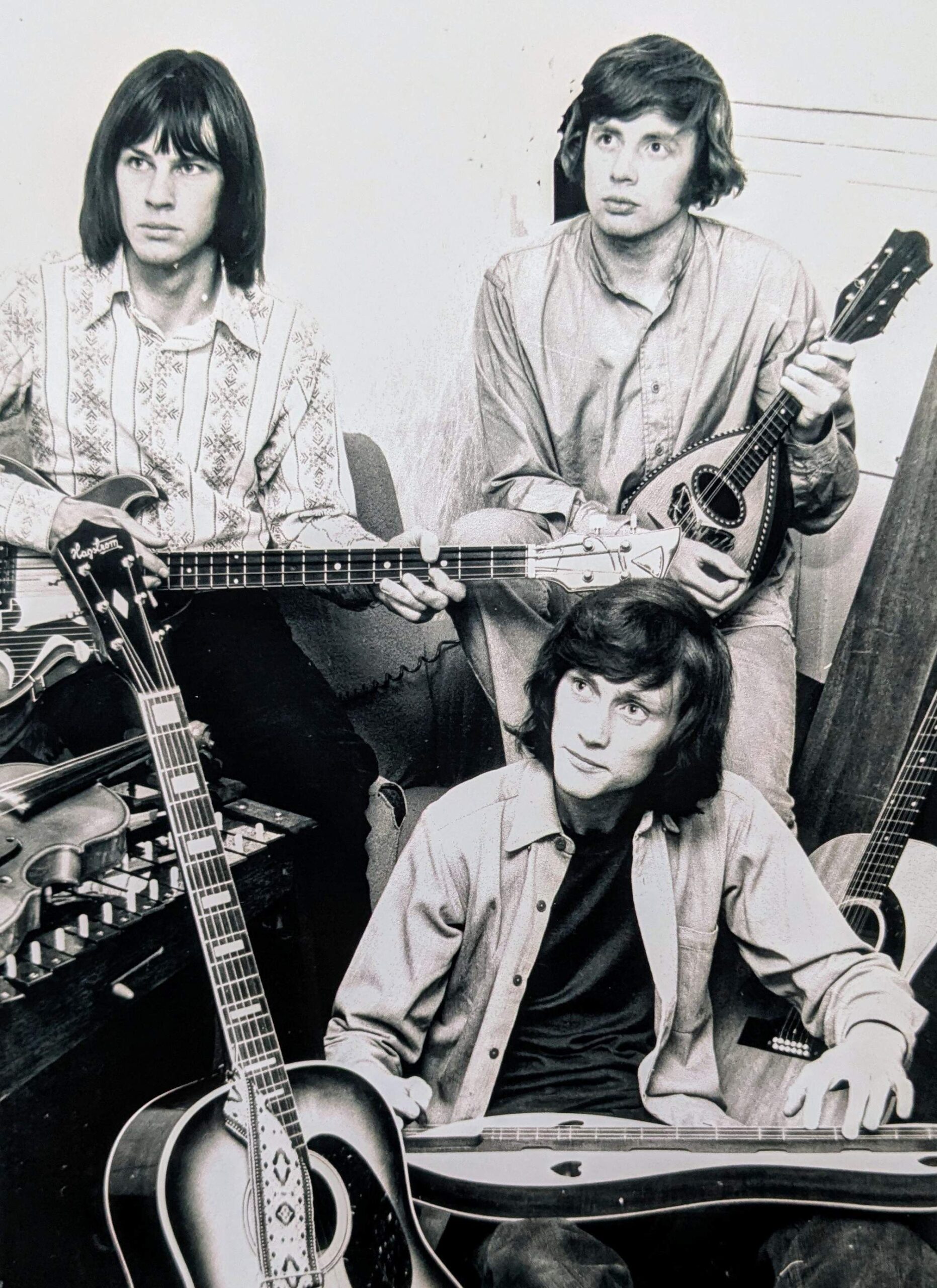

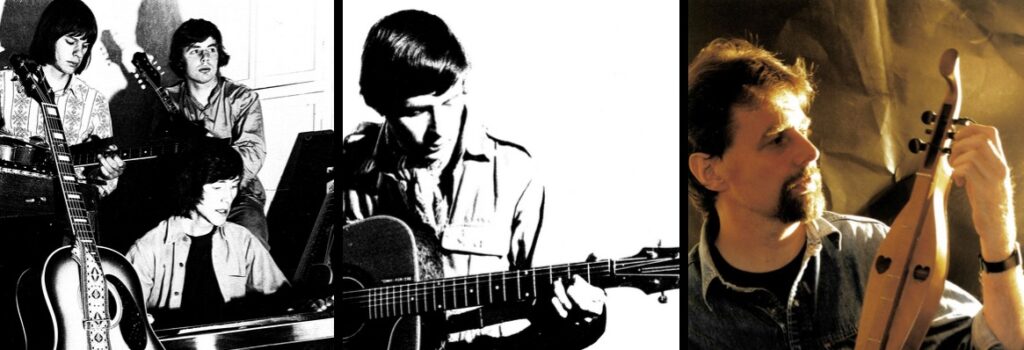

Headline photo: Dulcimer | The practice room at Narrow Meadow Farm.

Pete Hodge Website / Website 2 / Bandcamp