After Shave’s ‘Skin Deep’: The Forgotten Swiss ’72 Heavy Rock Monster

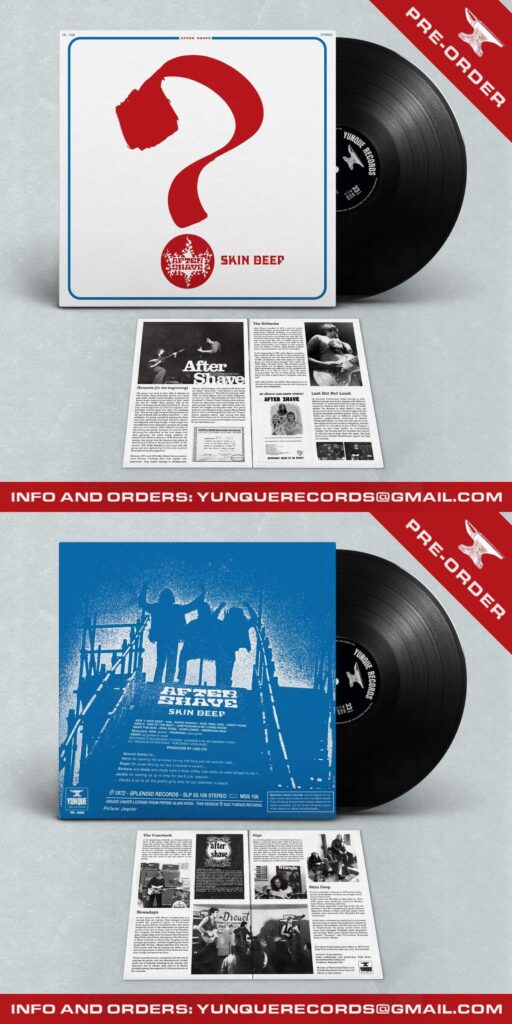

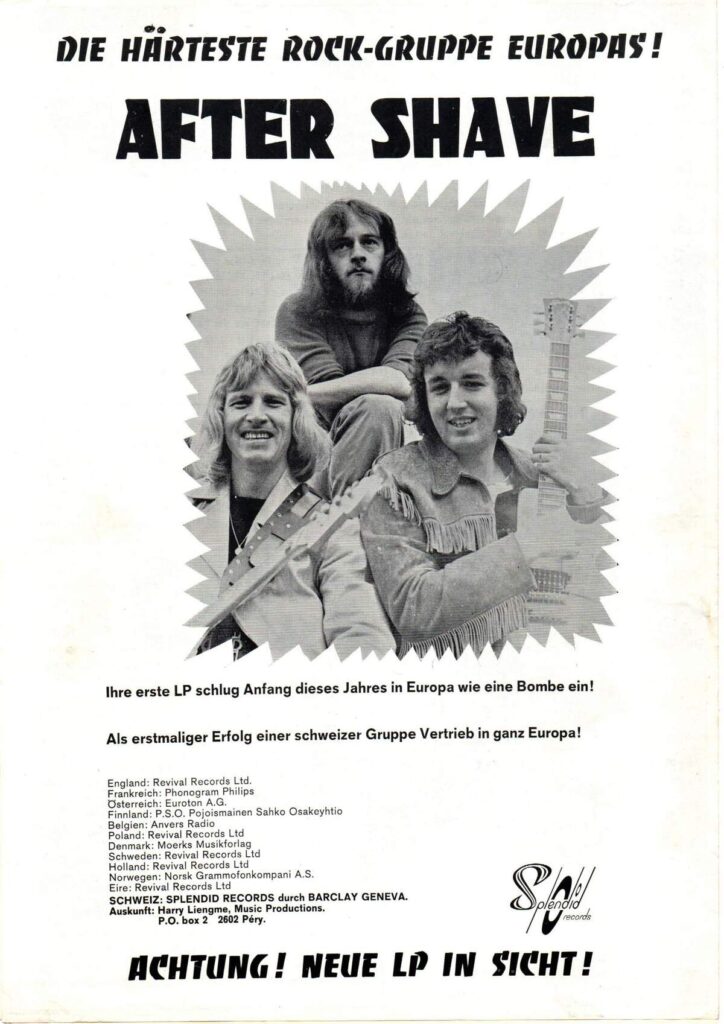

Ever stumble upon a record so heavy, so unpolished, it feels like you’ve unearthed a lost gem meant for only the true freaks? That’s ‘Skin Deep,’ the 1972 monster from Swiss band After Shave. Long forgotten, but now getting a well-deserved reissue from Spain’s Yunque Records on limited vinyl (pre-orders are live).

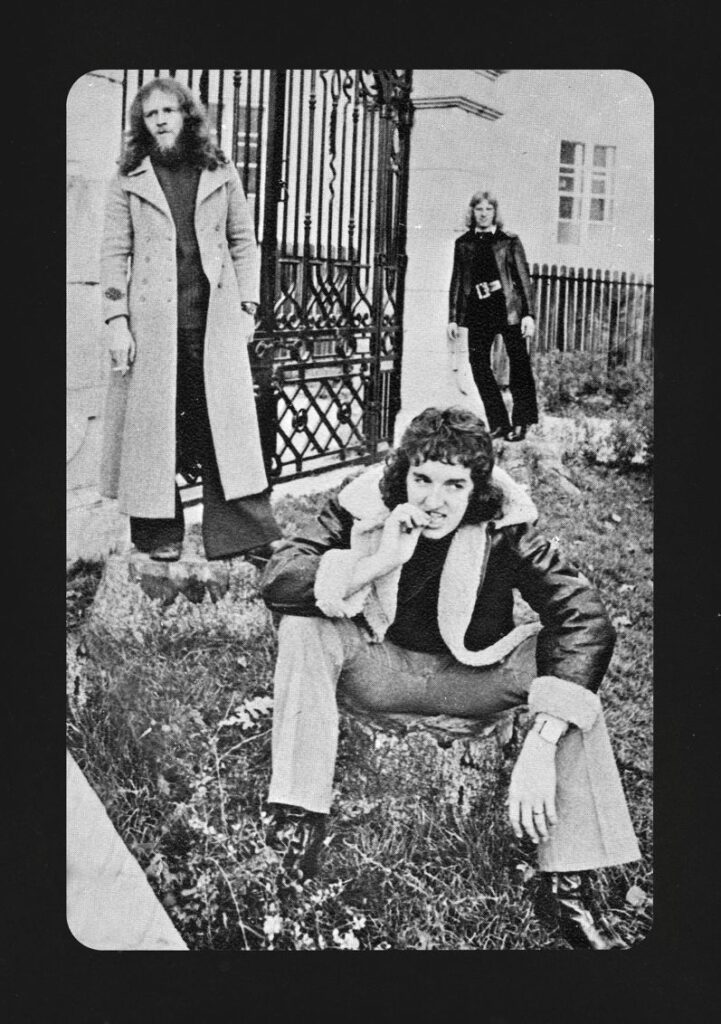

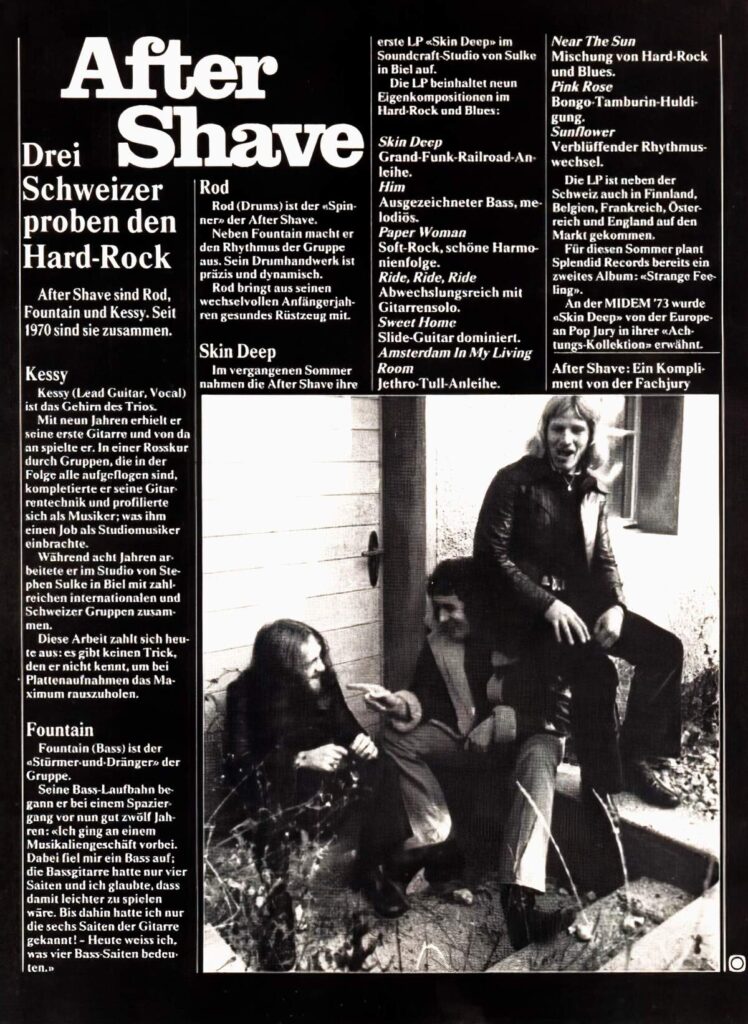

A Swiss hard rock band lost in the cracks of time, overshadowed by their own bad luck and the record industry’s usual cocktail of indifference and dumb decisions. This is as primal as rock can get—no-frills, no-bullshit just the right amount of barroom filth to keep things interesting. The kind of band you can smell through the speakers. After Shave crawled out of Switzerland in the early ’70s, back when Swiss rock wasn’t exactly making the cover of NME (or anywhere, really). They had it all—mean riffs, a tough-as-nails rhythm section, and that loose-but-tight energy that made the best power trios of the era unstoppable.

The first record, ‘Skin Deep,’ dropped in ’72, and gained some momentum. Further down the road, EMI showed interest—until they botched the deal. The tracklist got shuffled, and some of the best songs never saw the light of day. Then, just as they were about to hit their stride, the industry did what it does best: forced a name change, slapped a weird ‘Slick’ label on them, and killed whatever momentum they had.

By ’75, they were demoing new material in Geneva—ten tracks, a solid weekend of non-stop jamming. The sound? Less proto-metal, more West Coast, leaning into something almost resembling early Americana. And then—nothing. The industry shrugged, the tapes gathered dust, and the band went silent.

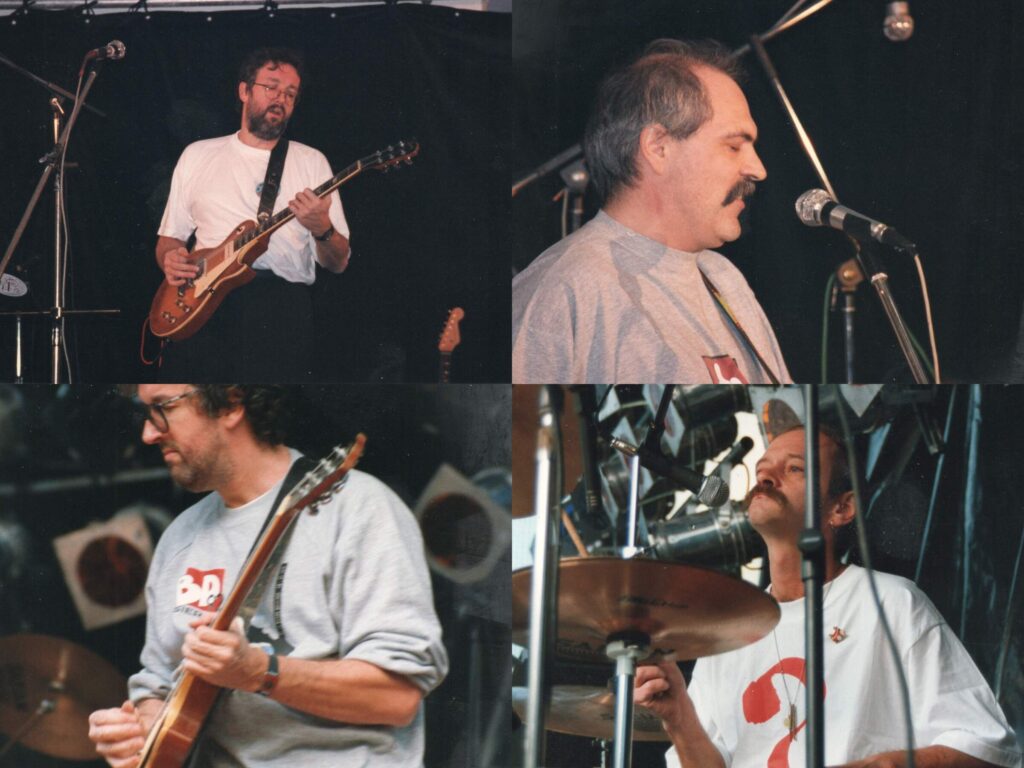

But here’s where it gets good. Unlike so many other lost bands, After Shave didn’t just vanish. They came back in the ’90s for a one-off reunion, re-recorded some of their old material, and let the legend grow in whispers among crate-diggers and European psych-heads. And now, ‘Skin Deep’ is back in circulation, joining many other in the heavy underground sanctuary.

Spin this thing loud and let it kill you.

“Music is our language.”

Let’s kick things off with a classic: how did After Shave first come to life in the wild days of 1968? Was it pure instinct or something more deliberate? You were clearly in a time and place that was alive with creative chaos. What was the vibe like in the early days?

Pierre-Alain Kessi: 1968 came about by chance. I had left a group (Les Vampires) at the end of 1967 following disagreements over musical choices and with the ambition of having more time as a studio musician—an occupation that was very formative and allowed me to meet many older and more experienced musicians (e.g., jazz guitarist Pierre Cavalli). In May 1968, André Pascal (Dédé), the drummer of Les Vampires, decided to leave the group and asked me if I’d like to play with him again in a new line-up with a singer (Bruno Züst) and a bassist (Noldi). It was with this short-lived but already blues-rock-oriented band that we took part in the competition mentioned below, playing nothing but covers—from John Mayall to Cream, Jimi Hendrix, and the usual suspects. At the time, there was a very rock-pop-psychedelic atmosphere in Biel, with lots of bands trying to make their way.

Let’s rewind a bit—before After Shave even existed. Where did you grow up, and what kind of places did you hang out in back then? Were you the type to loiter in record shops or sneak into local bars to catch a late-night set?

I grew up in Biel/Bienne, Switzerland, the biggest bilingual city in the country (French-German)—a working-class town (mechanical engineering, watchmaking) now better known for its production of Swatches and Rolexes than for music, although the winner of the Eurovision Song Contest, Nemo, also grew up in Biel/Bienne. At the time, there were one or two bars where bands could perform, which I, of course, frequented. A record shop was kind enough to let us listen to LPs all afternoon and on Saturdays. In other words, not only did we have the opportunity to listen to everything that came along, but we could also suggest what we wanted to buy. Reading Melody Maker was an extraordinary source of information at the time.

Was After Shave your first stab at a band, or were there other attempts buried in your past—those teenage garage bands that never quite made it out of the basement? Tell me about them. What were those early band names?

The very first group I was part of, between 1963 and 1964, (Les Mirages), was a purely instrumental group inspired by The Shadows. I was 15 years old in 1964. I was expelled from the group because I couldn’t play evening gigs—the age of majority to do so was 20 at the time. It was a blessing in disguise, as I was able to spend some time learning about blues, English rock, and the whole movement that followed. I then briefly joined another band in 1966, where I met Jean-Claude Fontana (Cacou). We later joined Les Vampires, a band in which Dédé played. The rest is history.

How did you come up with the name of the band?

Totally by chance. It came on its own, probably when I was shaving one morning.

I wanted a name that was composed, without the traditional The, and that would be instantly memorable to the public. After Shave seemed like the perfect choice.

The band’s first gig being a “pop contest” and getting disqualified with a critique about your distortion—what was going through your mind when you heard that? Was it a moment of frustration or more like “hey, we’re onto something”?

We actually took part in a rock band competition with the first group, which, for the occasion, was called “Bare Wires” (cf. John Mayall). Although the audience gave us an extraordinary reception, listening to a style that was new at the time, the jury—particularly the Chairman—complimented us on our performance but immediately pointed out that we couldn’t win first prize because I played with too much distortion, didn’t attack each note, and relied on sustain. Far removed from classical guitar techniques, I was to discover much later that, without knowing it, I was already abusing legato, pull-offs, hammer-ons, and bends.

I was frustrated not to win the competition prize (the equipment), but I was reassured in my approach to sound and the electric guitar.

“‘Skin Deep’ was their first release in the rock-psychedelic style.”

How did you get in touch with Splendid Records? What led to the album contract, and what can you say about the label itself?

From 1966 to 1976, I worked extensively as a guitarist in Stephan Sulke’s recording studio (a very well-known singer in Germany) and took part in numerous sessions for the Splendid label. The head manager of the label offered to release an LP of After Shave if I provided the master tapes. Splendid was a major label in Switzerland at the time, reissuing rock ‘n’ roll and popular music classics. ‘Skin Deep’ was their first release in the rock-psychedelic style.

‘Skin Deep’ is a record that’s become a legend in its own right. How do you look back on the making of it? Was it a reflection of the band’s identity at the time, or did you think of it more as a step in the journey?

Both at the same time—the identity we had at the time, mixing blues, rock, pop, and folk, and the desire to mark a stage in our development.

What’s the story behind Skin Deep? Where did you record it? What kind of equipment did you use, and who was the producer? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

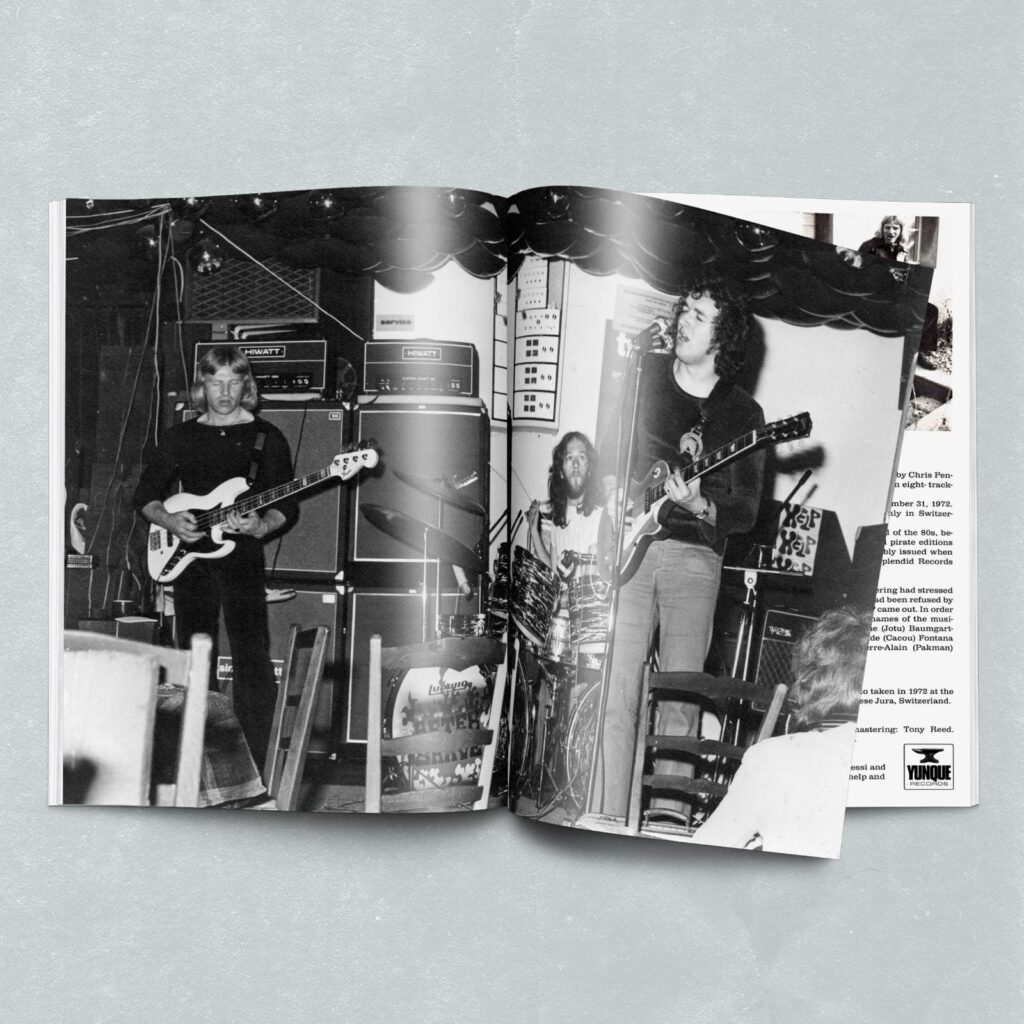

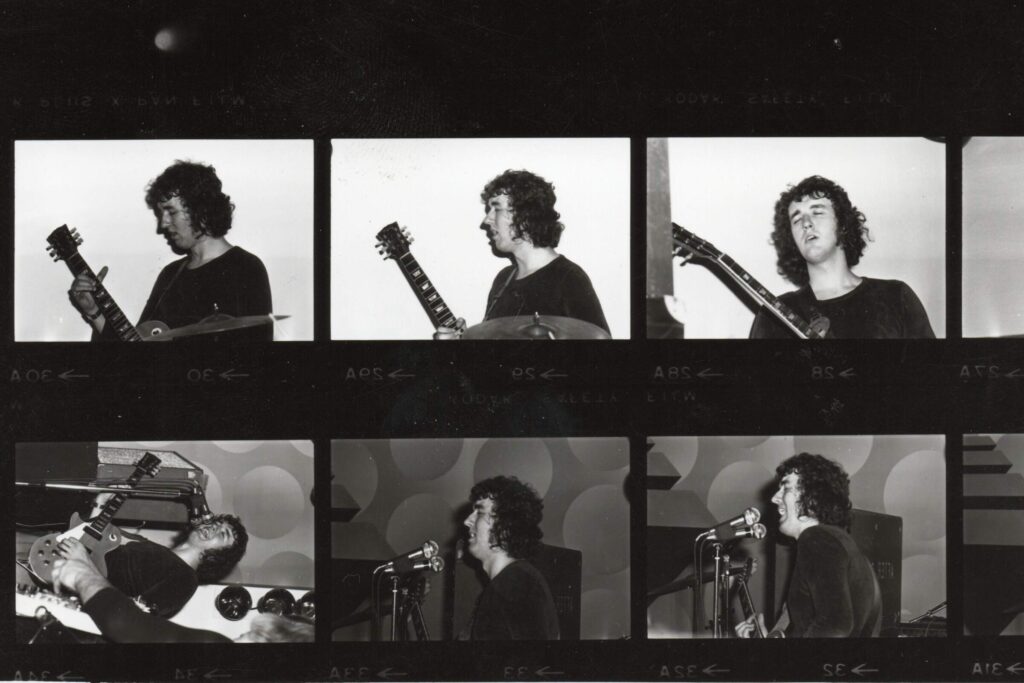

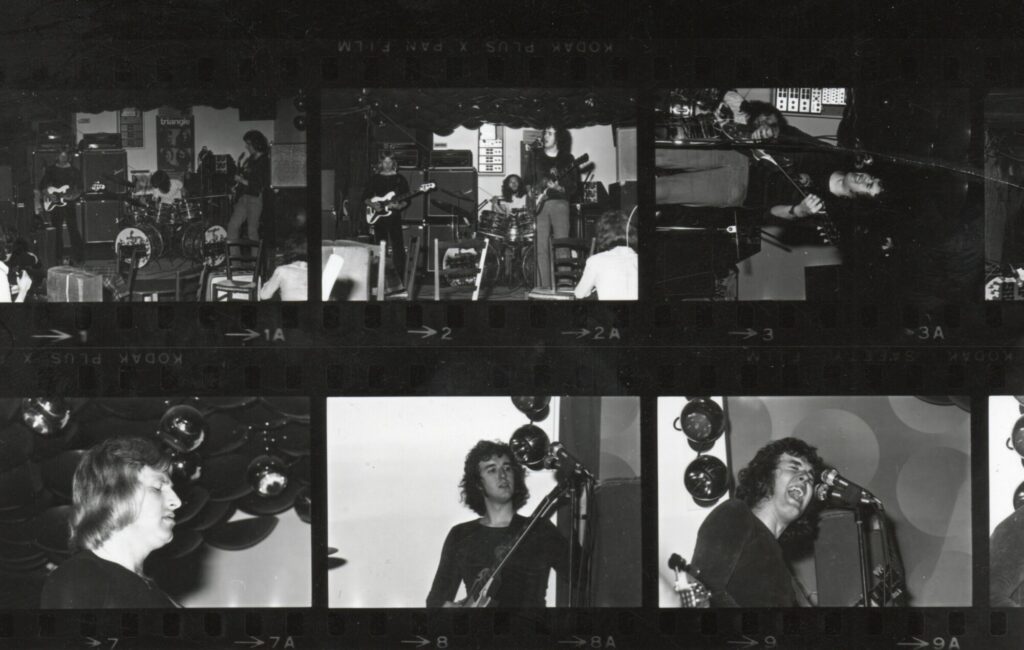

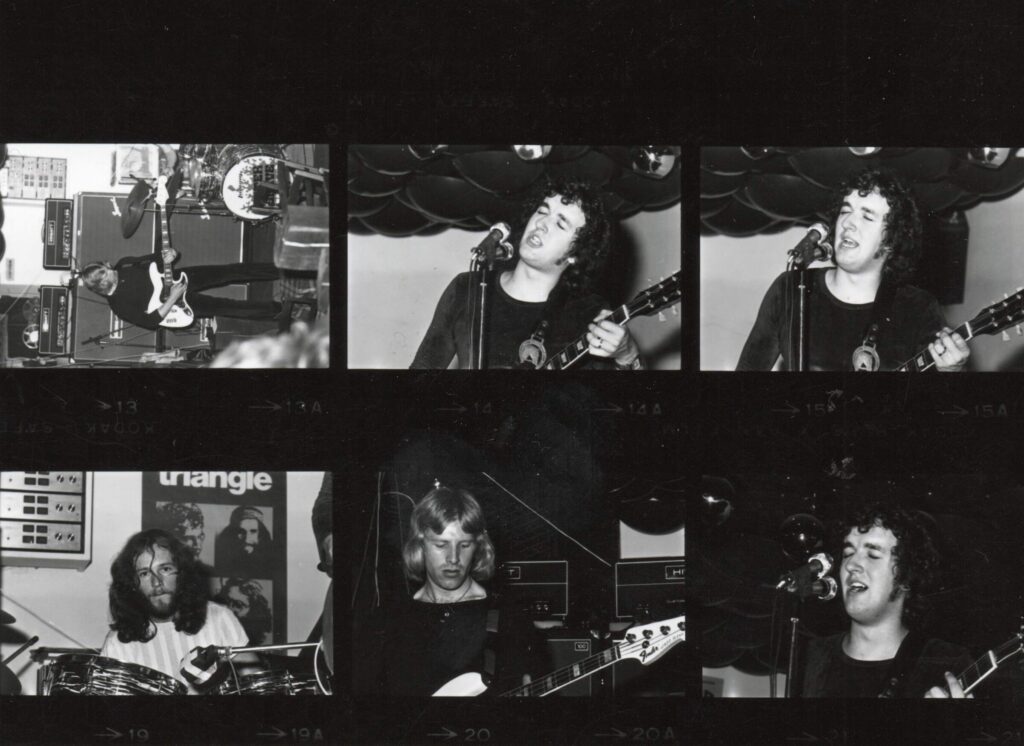

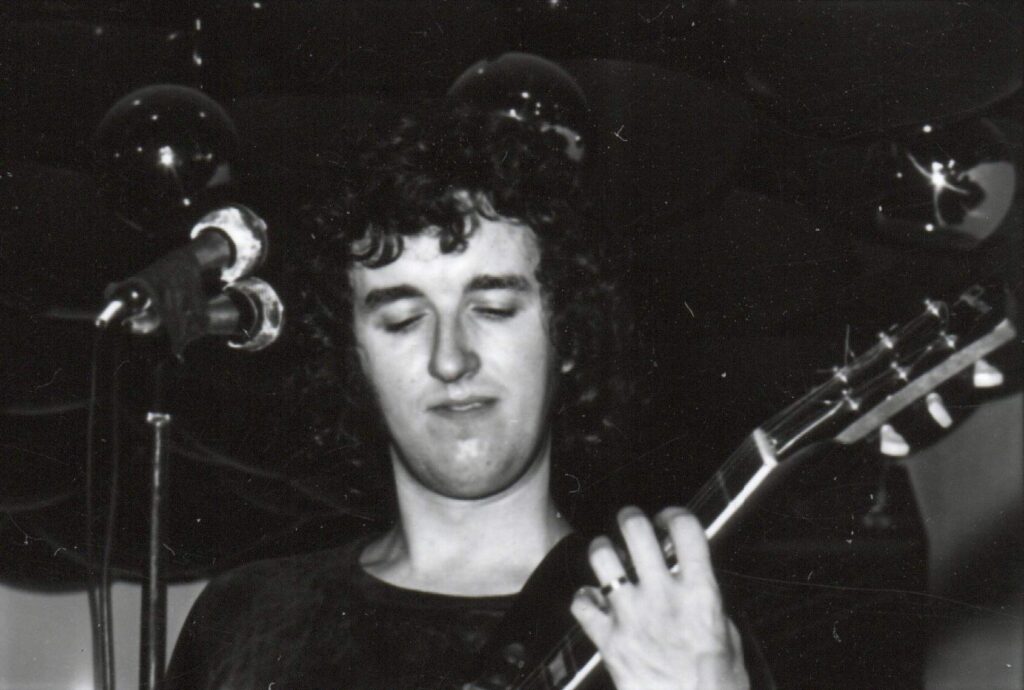

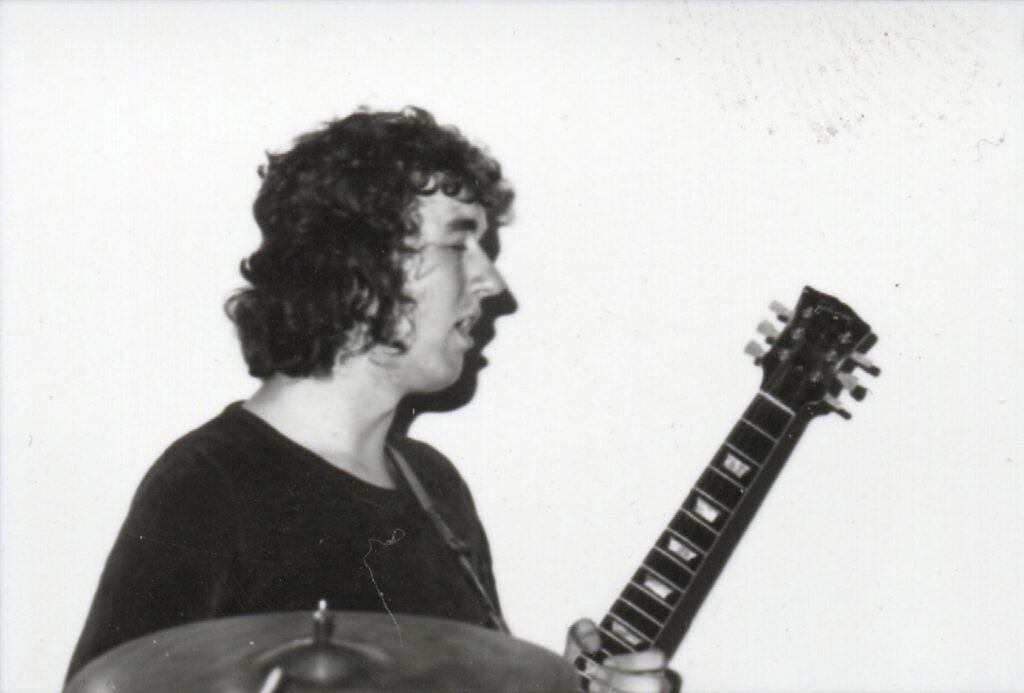

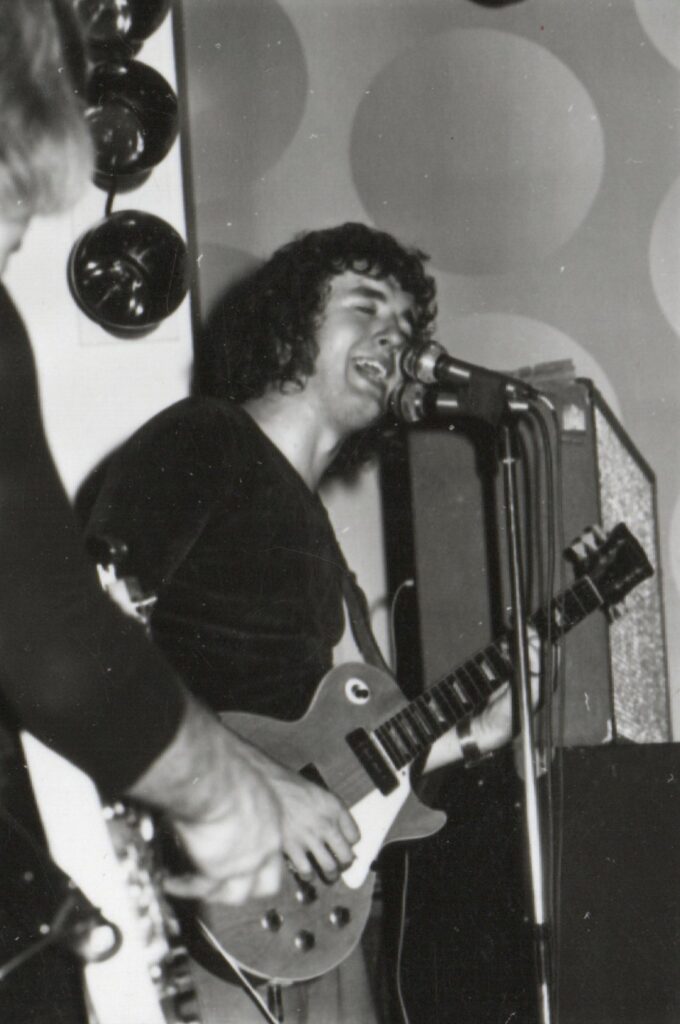

‘Skin Deep’ brought together a large number of my compositions from the period, which we played at our gigs. The recording took place at the Soundcraft studio in Biel in several sessions spread over 1971 and 1972. The studio had a 16-input “home” console, initially a Scully 8-track recorder and later a 16-track. I played a Les Paul Standard 1968, amplified by a Vox AC30, and a Framus 12-string acoustic. Cacou played a Fender Jazz Bass with Hiwatt amps, and Rodolphe Baumgartner had a Ludwig drum kit with double bass drums. I was the producer, along with our manager at the time, who handled the mixing. I can’t estimate the exact number of hours spent recording and mixing, but I think we put in about thirty hours.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

It’s difficult for me today to comment on the tracks on the album. But I still enjoy playing ‘Sweet Home,’ ‘Him,’ ‘Amsterdam,’ ‘Pink Rose,’ and ‘Sunflower.’ I think they’ve aged the best.

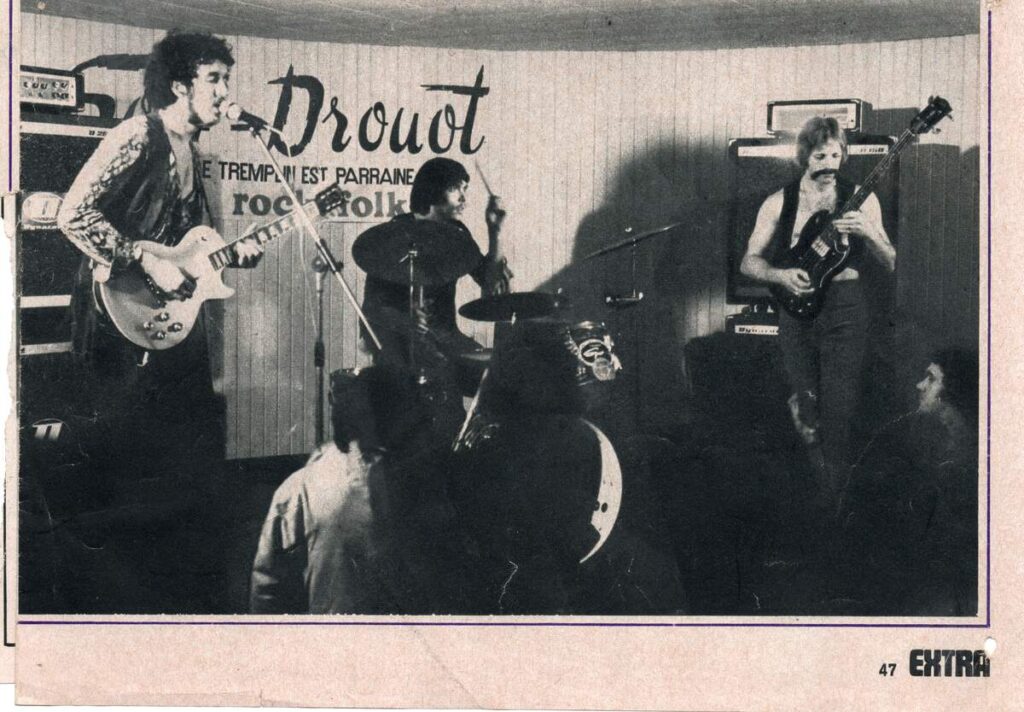

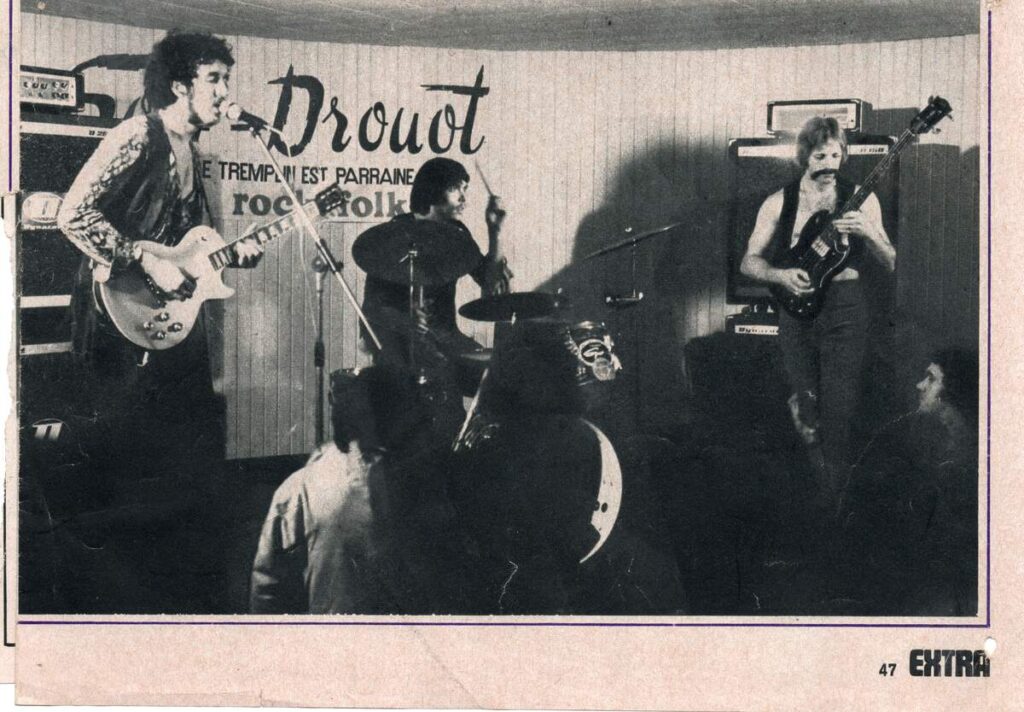

The 1970s were full of transitions for the band, from lineup changes to the infamous French Golf Drouot contest win. What was the feeling like during that time, especially when you won that contest? Did it feel like something big was about to happen for the band?

For me, the Golf Drouot stage was an opportunity not to be missed. Playing at this legendary venue, which had hosted some of the biggest names on the French and English rock scene, was a must. Winning this competition gave us the certainty that the band was on the right track. Unfortunately, it was also one of the last concerts with Dédé, who announced his intention to leave the band at the end of 1970.

Speaking of lineup changes, you eventually found a balance with Rodolphe Baumgartner. What did he bring to the table that fit with the band’s vision at the time?

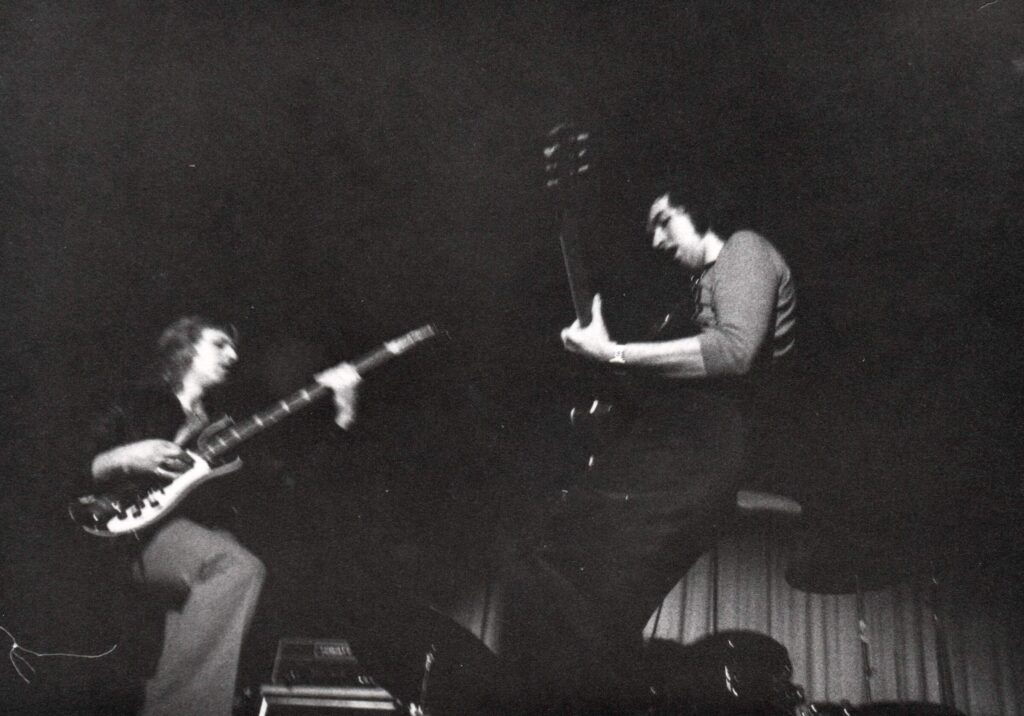

He brought a different drumming style—more energetic and square but less lyrical. The marriage with Cacou’s melodic bass was quickly established and reinforced the band’s hard rock direction.

Let’s talk about the ‘Strange Feeling’ LP. From the impounded tapes to the pirated version that popped up in the ’90s, that’s a hell of a story.

‘Strange Feeling’ was conceived as a sequel to Side A. Side B was given over to more heterogeneous compositions.

For the first time, the lyrics were written by the singer, Barrie J. Brown, and I had composed the music for two guitars. The recording took place in two phases in a studio in Antibes (France), which was supposed to give us a more international sound. In fact—and we didn’t know all this until much later—the producer, who had open claims on the studios in Switzerland, had made a deal with the French studio. As a result, the record was never finished on my part, and the tapes mysteriously disappeared until the appearance of a record on an Italian label which, without asking me anything, released this 33 with fanciful titles, a band lineup that was not the one that recorded the tapes, and, obviously, an unfinished production in the state of rough mixes.

What are some of the clubs you played and bands you shared stages with?

In Switzerland, we played in quite a few clubs and with some of the best-known bands of the time. Unfortunately, I don’t have any very precise memories—apart from opening for the Spencer Davis Group.

What would be the craziest gig you ever did?

An open-air concert in the city of Lausanne, under the Grand-Pont, with around ten thousand spectators.

What kind of gear and amps did the band have?

I always used my Gibson Les Paul, my Vox, and, incidentally, a wah-wah pedal. The bassist used a Rickenbacker and an Acoustic amp. The second guitarist had a Les Paul and an Orange amp. The drummer was still on Ludwig.

The shift from a four-piece to a trio in 1970, when you brought in Jean-Claude “Cacou” Fontana, must’ve been a big moment. What did that new configuration bring to the band’s sound?

More freedom to improvise, which was more in the air at the time.

Let’s talk about the singles you put out during those years. There was the first single that was recorded but never marketed due to a lack of funds—how does it feel looking back at that unfinished track? Do you think it had something special about it, even though it never saw the light of day? Then, you had the singles from the early ’70s that did get released. What was the process behind selecting the songs for those singles?

In fact, our method was to record the tracks we’d tried out live, either to produce an LP at a later date or to make a 45. It was the label’s decision to produce one or another of the tracks as a single.

You’ve seen a lot of changes in band members, with Rodolphe “Jotu” Baumgartner joining in 1970, then Barry James Brown on vocals, and Sylvano “Gugus” Paroni replacing Cacou. Each member brought their own touch to the sound. How did you navigate those shifts and find a balance in the band’s chemistry, especially when different members had their own strong personalities?

The evolution was permanent. Barrie brought a higher quality to the vocals and different lyrics—less psychedelic and more focused on ordinary life. Silvano brought a bass that was more rhythmic than lyrical. The style also evolved, with a more melodic approach and more elaborate arrangements.

That EMI moment with the name change to Slick—it must’ve been a real head-turner when you heard that they wanted you to change your name to sign. How close did you come to actually pulling the trigger on that one? And what happened with that deal?

In February 1975, we recorded two demos, ‘So You Gonna Way’ and ‘Ain’t Ready for You Yet,’ in which we used keyboards for the first time—a sound more suited to the times, with Moog and Mellotron in addition to the piano. The demos interested the EMI label. Unfortunately for us, we arrived a little too late, as they had signed another band that was just starting to make a name for itself. Just missed out…

After Shave might’ve taken a hiatus, but your career didn’t stop. You’ve played with legends like Mory Kanté and even won a contest for your Clapton cover.

After the band broke up due to a lack of funds, I continued to play in several bands and, in 1998, I won a competition organized by the French magazine Guitarist for a black Stratocaster (Blackie) autographed by Eric Clapton himself. I had recorded a cover of ‘Badge,’ which won unanimous approval from the jury.

Fast forward to the 1990s and Twenty Years After—how did it feel to revisit the old material and give it new life? What was it like to hear those songs again after two decades, and did anything about them surprise you?

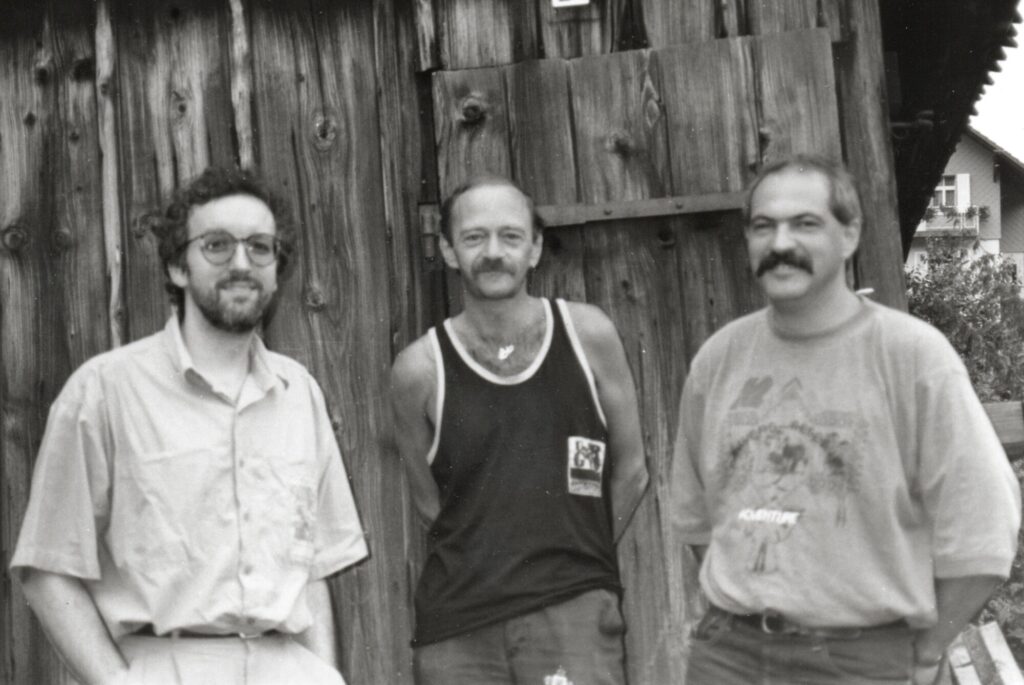

After a dozen years apart, Rodolphe, Silvano, and I jammed together to celebrate my 40th birthday. Following this jam, we decided to get the band back together and, as we had no recent support, we decided to re-record some of our old songs. This enabled us to play live again until Rodolphe’s death at the end of 1999.

The concept of After Shave today feels more like a personal reflection of you and your journey rather than just a band. How do you navigate that, especially when fans want to hear the classic sounds of the ’70s versus your current material?

The band is dormant most of the time, and we revive it when the occasion or the desire of one of us arises. It’s always a pleasure to play our old tunes, to which we always try to add a little something extra.

Your admiration for guitar legends like Hendrix, Clapton, and Peter Green is clear in your playing. But if you could sit down with one of them for a jam session, who would it be, and what would you want to play together?

It’s a difficult question to answer, but I’ll try anyway. With Hendrix, certainly ‘Red House.’ With Clapton, ‘Badge.’ With Peter Green, ‘Need Your Love So Bad.’ But I have no such ambition.

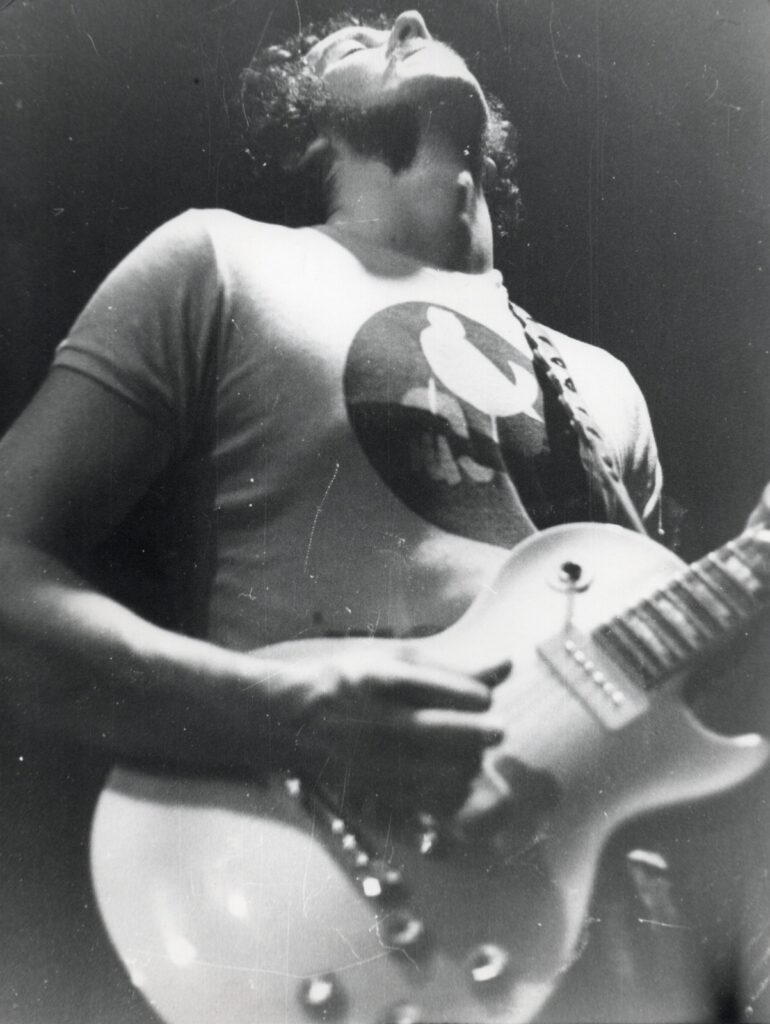

When it comes to your guitar playing, the bending of strings and intense vibrato are unmistakable. Do you remember when you first started developing your signature sound, and was there a particular moment when you realized, “This is it—this is my sound”?

I started to really develop this style when I listened to the Yardbirds’ 45 ‘For Your Love.’ The B-side was devoted to an instrumental composed by Clapton, whom I was discovering at the time, called ‘Got to Hurry’—the beginnings of Clapton’s sound and style in 1965, which he later perfected with John Mayall. That sound has stayed with me ever since.

I’m never really satisfied with my sound or my playing. I’m always looking for perfection. There are concerts where I tell myself that it was very close. That’s what motivates me every day.

Your current trio sounds like a real powerhouse, with Silvano Paroni and Mario Lepore backing you up. How do you describe the chemistry between the three of you when you hit the stage together? What’s the magic that happens in the moment?

The three of us are old veterans of the stage. The chemistry comes back as soon as we get together. Music is our language.

Looking back at your whole career, from the first disqualification to the triumphs and setbacks, how do you feel about the legacy of After Shave? Is there anything you wish you could go back and do differently, or has it all come together in a way that feels right?

I’m still amazed at the interest in this band and the LP after all these years. I never had a career plan—back then, we just thought we’d play for a few years and enjoy the good times. So I can only be satisfied with where I’ve come from, and since we can never undo the past, let’s leave it alone.

If you had to sum up what After Shave has meant to you personally, what would you say? Has the journey shaped you in ways you never expected when you first picked up that guitar?

Obviously, it was a very important stage in my life as a musician. It was a very formative experience at a time when creation and pleasure took precedence over business. I didn’t expect to still be playing guitar at 75 when I first picked up a guitar—a simple nylon-string classical guitar that belonged to a distant cousin. At the same time, the Shadows were hitting the charts with ‘Apache’ and that incredible sound. My quest began. And it’s still not over.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

As for my favorite piece, I think it’s ‘So You Gonna Way,’ based on a suite of fourths of a major 7th.

Is there any unreleased material?

Before Slick disbanded, we recorded around ten demos in Geneva. We were invited for a weekend to test the facilities and equipment of a new studio, and we played for almost 48 hours without interruption. Unfortunately, the events that followed didn’t allow the demos to come to fruition. The style of the tracks recorded is very different from what we were doing at the beginning—more West Coast-oriented. Today, it sounds like Americana.

Thank you for your time. The last word is yours.

Thank you for your interest in the group and in my humble self, and for bringing back a few memories.

Klemen Breznikar

Yunque Records Facebook / Instagram

Cela fait vachement plaisir de revoir et de se remémorer ces vieux souvenirs ! Merci et bonne continuation ! Félicitations et cordiales salutations