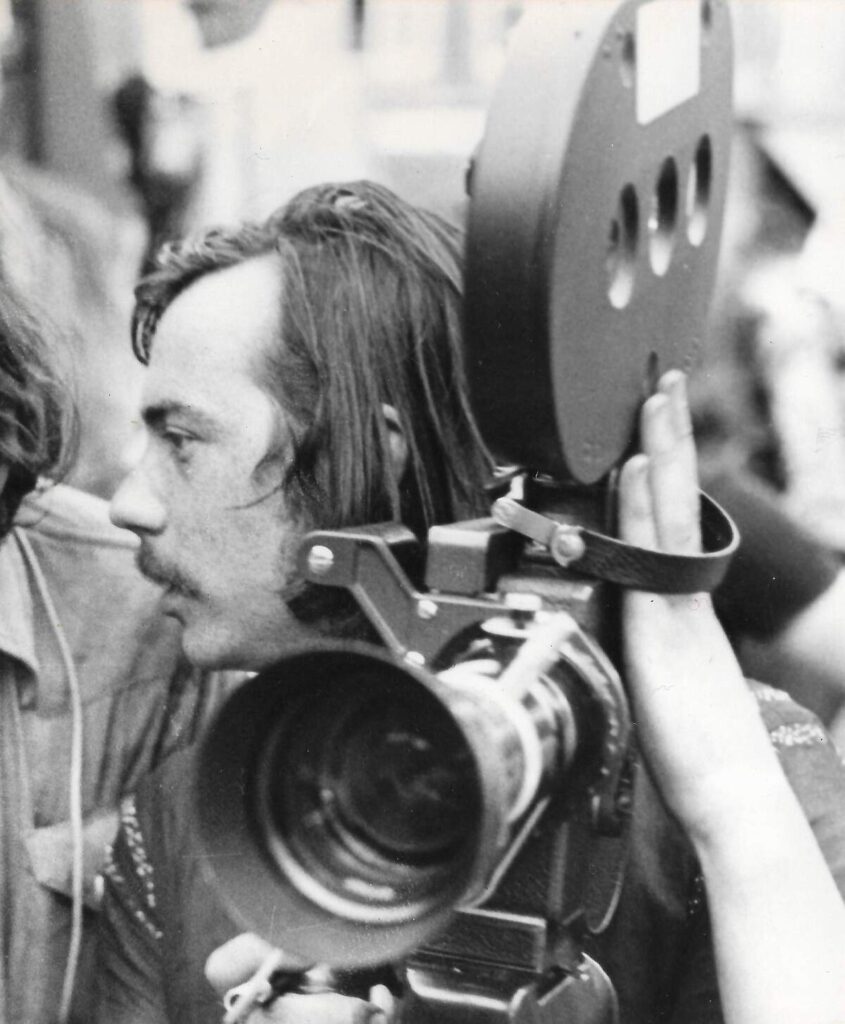

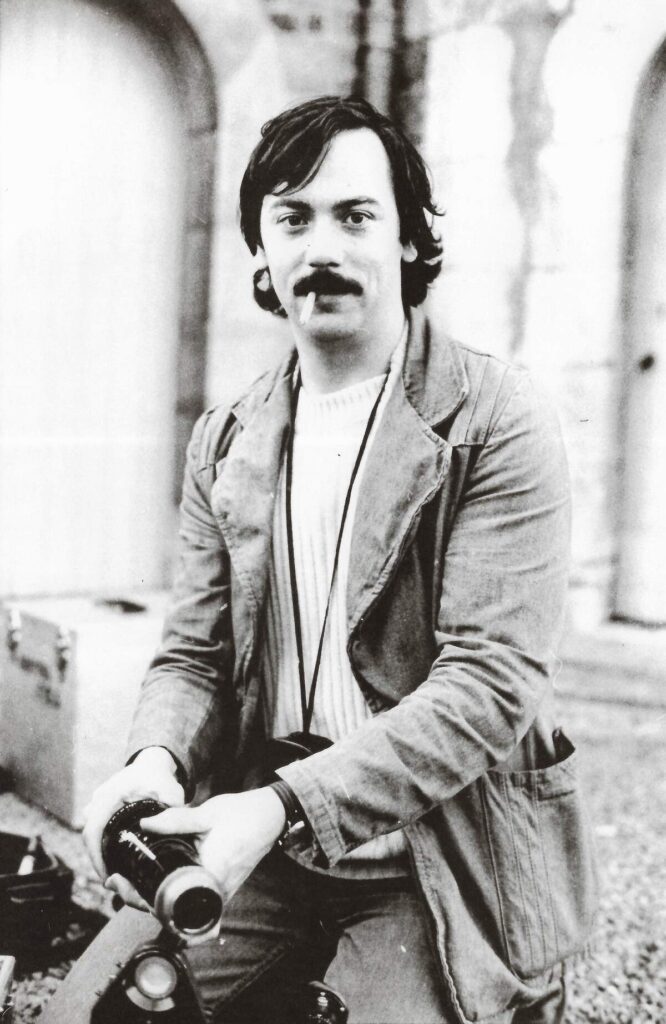

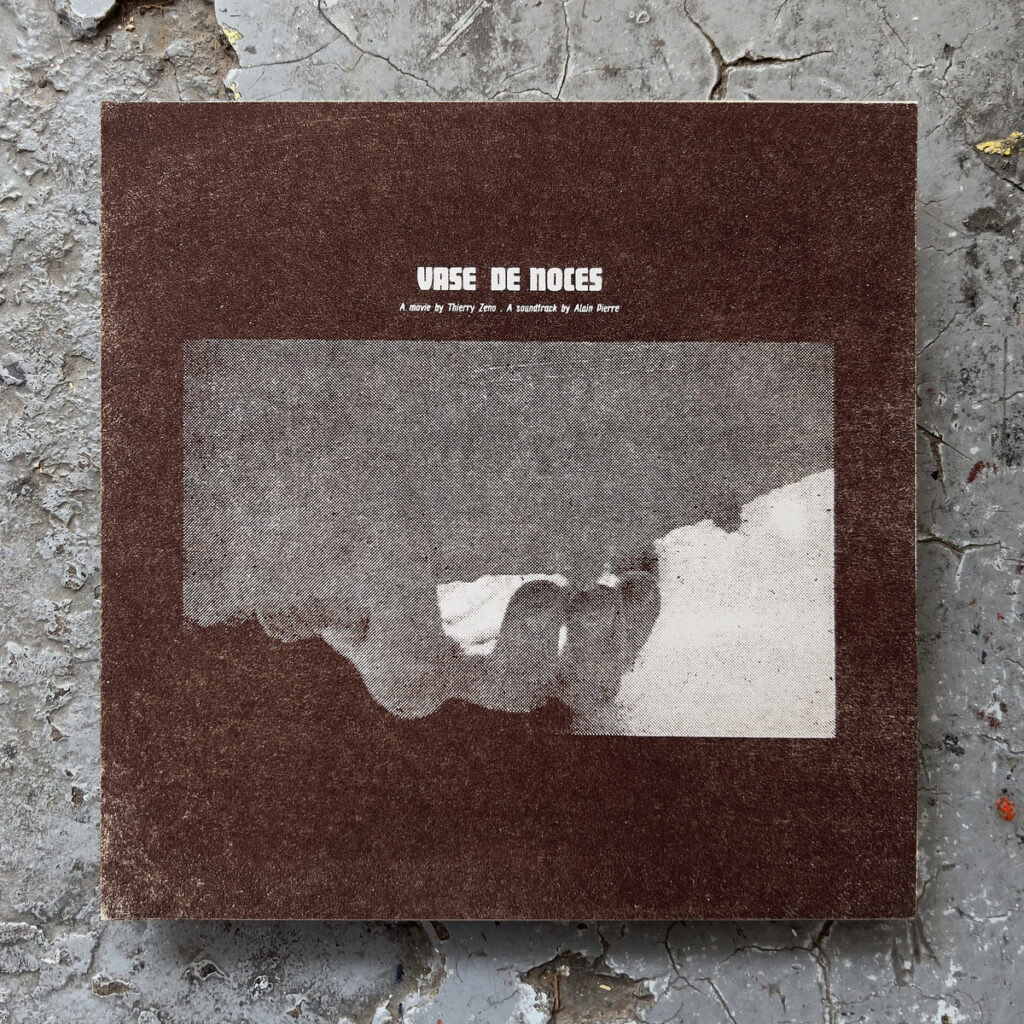

Alain Pierre: Composing the Original Soundtrack for ‘Vase de Noces’ – The Sound of Thierry Zéno’s 1974 Cult Film

Alain Pierre’s soundtrack for ‘Vase de Noces,’ the 1974 Belgian cult film by Thierry Zéno, reemerges in a stunning limited edition that highlights both its experimental nature and its creator’s unique approach to sound.

Pierre’s work for the film, crafted on a shoestring budget, is not merely music but an immersive “sound object,” merging seamlessly with the unconventional visuals. Zéno’s use of discarded 16mm film stock mirrors Pierre’s unorthodox techniques, employing everything from distorted bottle sounds to manipulated classical music, creating an unsettling yet deeply engaging auditory experience.

Pierre’s refusal to “sell his soul” for commercial success marked his approach to personal projects, making his music deeply authentic. The soundtrack’s avant-garde, visceral textures invite listeners into a world where sound blurs with silence, challenging traditional boundaries. This reissue offers not only a rare piece of Belgian cinema history but also a reminder of the power of uncompromising creativity in the face of limited resources. The release, with its handmade sleeve and accompanying booklet, ensures this pioneering work endures as a testament to Pierre’s artistic legacy. Learn more in the following interview, which delves into the life of Alain Pierre.

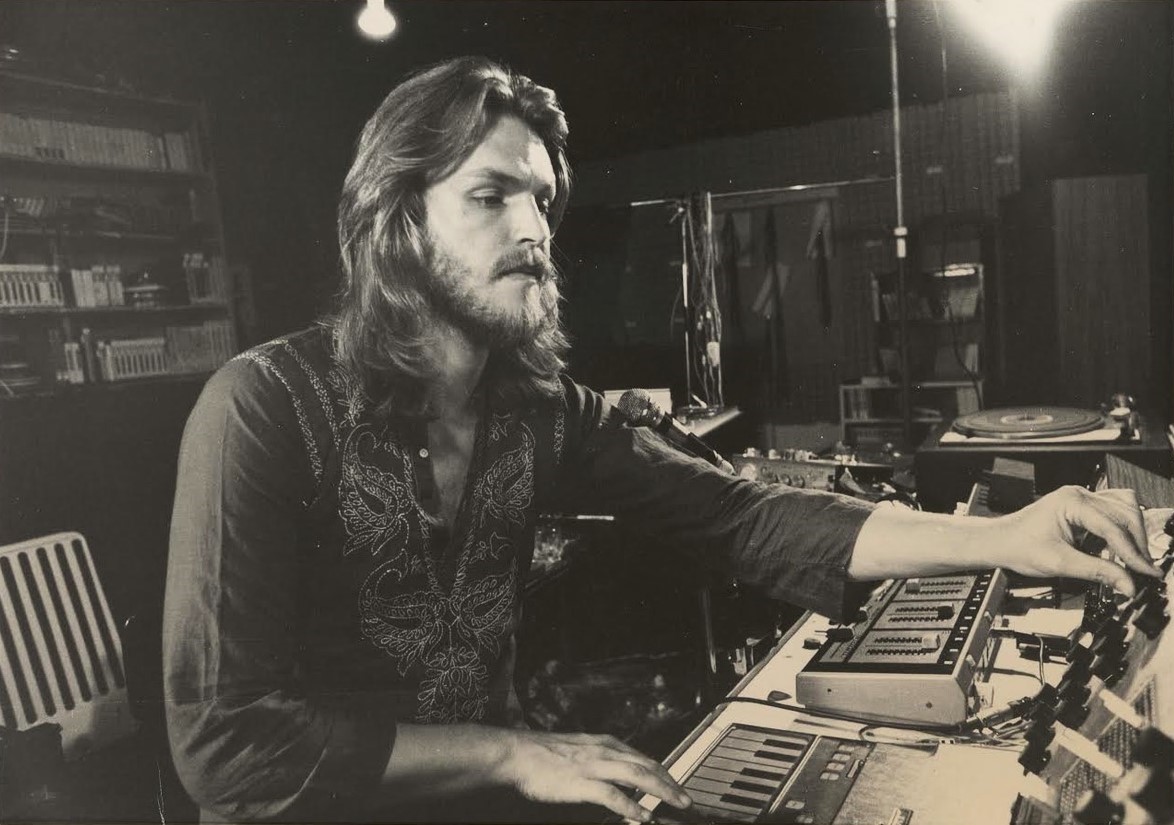

“Sound manipulation was an important term in his life.”

What do you think makes the original soundtrack unique, especially in terms of the mix of early electronics and baroque influences?

David Maurissen: I’m not a musician at all. When I was 16, it was my dream to become one; I tried to make computer music for 3 hours, and nothing came out. I knew I would never be a musician. But that’s not the point. I used to work with different music labels, and from day one, relationships and emotion have been the fuel of my involvement. Clearly, in this case, it’s both. I don’t know anything about baroque music (and just a bit more about early electronics). But when I heard the soundtrack for the first time, I was like, “OK, that’s something unique.” It feels like timeless music. It’s clearly old, but it still sounds fresh, probably because of this weird collage of genres. You can hear that something is “not right” in the baroque songs, even if you don’t know anything about it. The composition seems normal, but the sound, the voices, are too strange to be a classical interpretation. You can feel that the songs aren’t taken straight from an LP or a CD. So, when Alain explained to me the production process, they didn’t have the rights to use the proper songs (perhaps edited by— for example—Philips Music or Deutsche Grammophon). Therefore, they had to reinterpret all of them. It’s so “cool,” very DIY, and it gives this very strange sound. Also, this collage of early electronic and manipulated field recordings (which aren’t field recordings at all—there is no direct sound in the whole soundtrack), mixed with this strange baroque music, in 1974, must have been something very bizarre or maybe avant-garde (even if this term is now overused).

In your view, how does Alain Pierre’s approach to sound—such as using manipulated field recordings—reflect his artistic vision?

Tatiana Pierre: My father always told me that he used his synthesizers and electronics as instruments, not to replace instruments. He liked the fact that he could manipulate those instruments the way he liked it, with his interpretations of how, eventually, an instrument could or would sound as well. Sound manipulation was an important term in his life.

David: According to Alain, there isn’t a direct sound in the whole soundtrack; every sound is made with a synthesizer (2 EMS Synthi AKS, actually) and some effects modules. Alain loved to talk; a life filled with music and sounds. He once explained to me what made him become a musician. As a child, he saw a scene from a film involving an airplane. The plane was about to take off (or land, I don’t remember very well), but the sound wasn’t the real sound of the plane. Alain told me that he then realized that images without sound can be “lost” — that it’s the sound that makes everything about the feeling you get when watching a movie. And then he said, “For instance, if you had changed the sound of the airplane’s motor to one that loses power, instead of taking off, your feeling or impression about what’s happening to the plane would have been totally different, as would your story. It’s the sound that makes you tell a story, not just the image. That’s when I realized I wanted to be a musician and work with sounds.”

Were there any challenges or surprises in the process of restoring and reissuing this soundtrack?

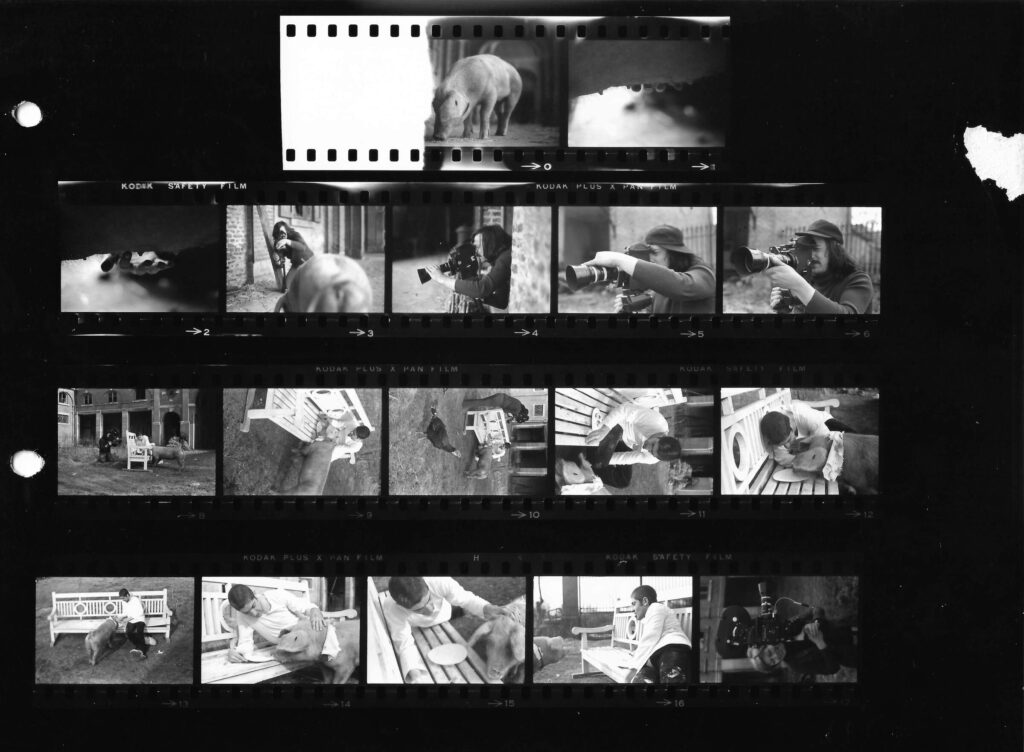

David: It was a very particular journey. Quite long and full of new encounters, but also very sad. We watched the movie together to point out what sequences should or shouldn’t be on the LP. When we exchanged notes, we all had the same ones. We knew that only the moments that would work without the images would be chosen. Therefore, the selection was quite simple and fast. Alain’s work was very well archived and organized; everything was there, with him, in his living room. So, getting the files was no problem. Getting the track names and composers was more challenging. Thankfully, Nicolas Jonard, Thierry Zéno’s son, and Christophe Piette were very helpful in finding documentation. That’s how we also had the idea of making a booklet to come with the record. We had some great images and an interview with Alain (conducted by Christophe). On behalf of the music, it wouldn’t have made sense not to share it as well. Unfortunately, when Alain passed away, just two months before the record was finished, I got in touch with Tatiana, one of his daughters. She was completely aware of the project, and when we met her, with Christophe, we all knew why we had to pursue this project to the end.

What was your father’s vision for the film and its music, and how did it evolve during the creative process?

Tatiana: Not very easy to answer, as I was 1 year old when the movie was made. How I imagine it went (because of recorded interviews, stories I hear about him, and what I’ve seen myself) is that he always listened to what a director wanted. He would never immediately impose his own idea, but most of the time, he immediately saw how he would work on a project. When somebody would be very stubborn with a vision, my father would then make a 1st draft of their ideas, then ask, ‘So, what do you think yourself?’ And if he sensed hesitation or felt the person wasn’t happy, he often already had a first draft of what he thought it had to be. Most of the time, he got what he wanted.

As he had a very deep love for filming and writing himself (and a strong character), I know for a fact he wanted to be involved as early as possible in a project so he could help with re-writing, pre-production, etc. Thierry was open to that, and I think that made the creative process easier for both of them.

How did the financial constraints under which Vase de Noces was made influence the music that was created for it?

Tatiana: As he states himself in the interview for Sub Rosa, it was more or less a coincidence, as he was working on baroque music for another soundtrack, and Thierry liked it. So, it was a “on the spot” decision.

My personal opinion is that, back in those days, there was plenty of room to experiment. Most of the electronic devices were new, the road wasn’t ‘set’ yet, and when you start, I think you begin with what you know. My father was educated in a strict Jesuit school environment, where he excelled in music, especially in the choir. I’m convinced that, somewhere, consciously or unconsciously, he liked the fact that he could manipulate music pieces. When you listen to it today, it may sometimes sound “clownesque” or even silly, but I hear confrontation and bending frustrations into melodies.

Can you tell us about any specific anecdotes or interactions your father had with Thierry Zéno during the making of the film?

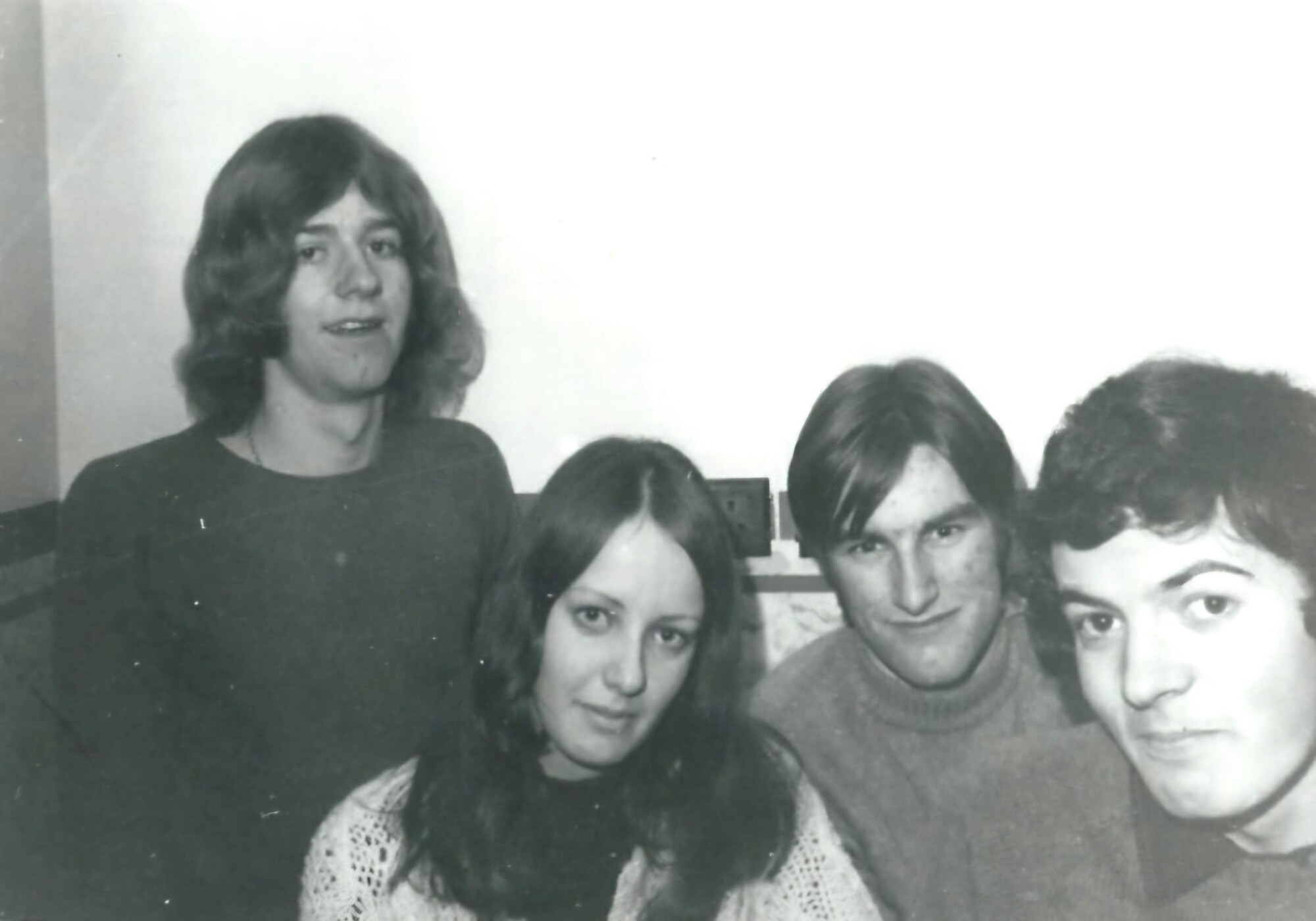

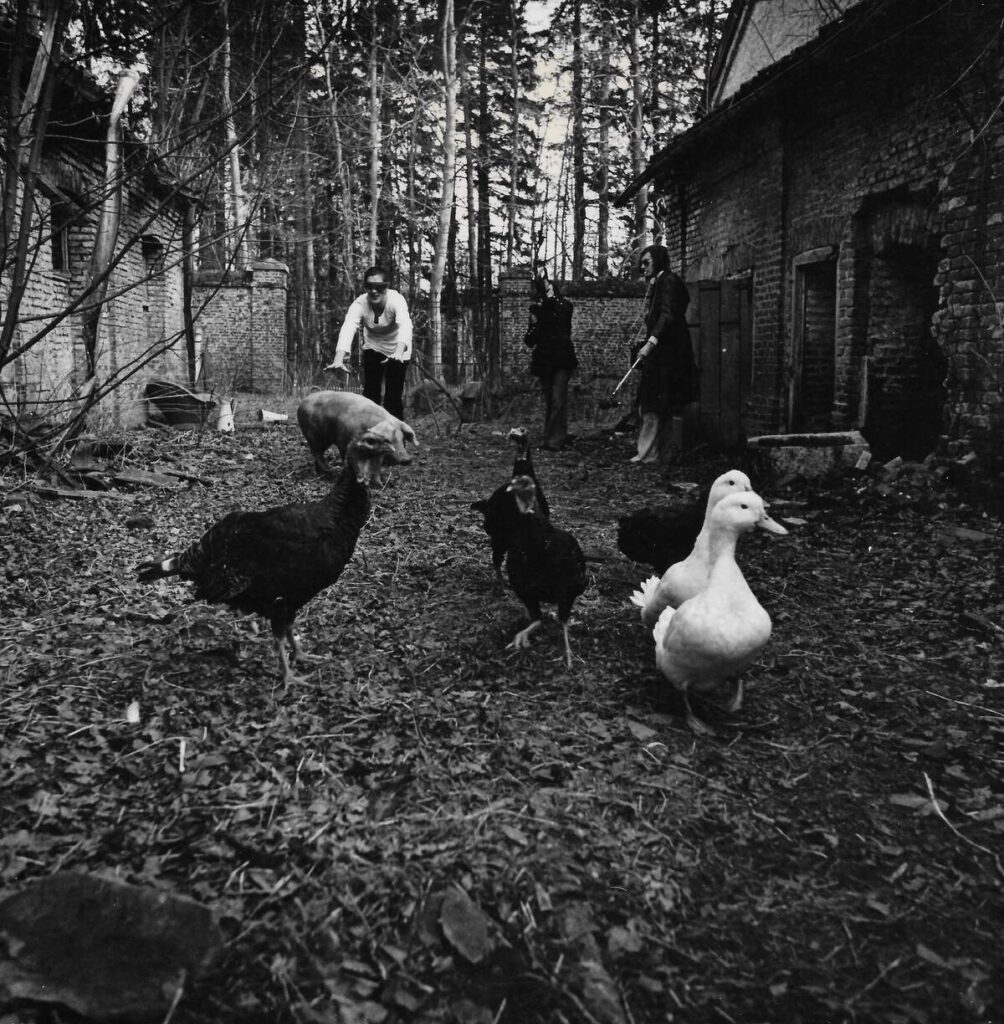

Tatiana: From what I know, they respected each other’s views a lot. ‘Vase de Noces’ is a perfect example. Back then, the movie was seen as grotesque and even banned, and again, even in this age as well. I see two young men trying things out, experimenting, searching for styles, and dealing with demons from their own past. And for some reason, I don’t think it was their intention to do it purely to shock or get attention or tell a story that had an exact explanation. Their interactions, for me, are that they didn’t have to explain to each other where the subjects came from or what the bigger picture was: they both felt no boundaries where needed between them, and for this, they could both experiment and create at the same time.

What do you think your father would say about this vinyl reissue project if he were here today?

Tatiana: He was able to follow the whole process, and I know he was happy, proud, and satisfied. Unfortunately, he did not make it to see the record come out and make it to the event.

David: Alain was very enthusiastic about the project, from the beginning. Unfortunately, for many reasons, this project took so long to become a reality. Some projects are like that… As the release is a collaboration with SubRosa, it’s their sound engineer, Gabriel Séverin, who took care of the sound restoration. Alain was really blown away. He was so happy with Gabriel’s result. Of course, he was quite hesitant at the beginning. As sound had been everything for him—his whole life—he thought, “Why should we ask someone else to take care of my work?” But when Gabriel sent the files, Alain called me immediately to say how happy he was. For the artwork, I had the idea of the image and texture almost at the start of the project. But like I said, it took so long that the sleeve project stayed in a drawer for months (or years). When production started, I could show Alain the finished sleeve, and he was very, very happy with it. The booklet, I couldn’t show him the project, but we talked with Tatiana and Christophe, and we all agreed on the proposed template. Tatiana explained to us that one of the saddest and most beautiful things about this project is that ‘Vase de Noces’ was Alain’s first professional project and also his last. Like the circle is somehow complete. There is also a sticker I’m not sure about. I designed an informative sticker to put on the cover so that people would quickly know what it’s about. When I went to CINEMATEK’s archives, I found a little press note where the movie was rated “X” or “Swedish movie” or “porn.” Even more, a “State-aided porn movie”… I decided to use it to catch people’s attention on the sticker. When I gave a record to Louise, Thierry Zéno’s daughter, I told her that we were still waiting for the sticker. She then told me, “I don’t think Thierry and Alain would have approved this quote as an advertisement.” Since she told me that, I never used the stickers on my copies. To be honest, I’m very happy and feel honored to have completed this project to its end.

For you, what does this reissue mean personally, and how do you think it contributes to your father’s legacy?

Tatiana: To be perfectly honest, it was bittersweet and harsh.

My father passed away on February 14th this year, and the album’s release and event were set for June 6th. Not even four months between the two events. Louise and Nicolas (Thierry’s children), his wife, and myself were invited to the event. We decided to meet a couple of weeks beforehand, and I’m happy we did. We got to talk about our fathers, our lives, and how in some way they influenced us. Louise suggested using two interviews she had from our dads and combining them into one, so we could get the audience to listen to them, explaining their own intentions on the projects. Although the interviews were taken at different times, it was magic to hear it come together. You could understand why they would collaborate on different projects together. Before he died, I had some specific conversations with my father about his legacy. As he was pretty much a control freak about his own work, he was proud that ‘Vase de Noces’ would be released. When a producer would come his way, it was often with the question of bringing out the “special ones,” and my father was always enchanted to go in that direction. Always on his terms, of course.

One summer ago, he gathered me and my sisters around at his place, where he still worked in his studio and lived, to talk about his musical legacy. I asked if he would object to the music he was little known for being released. He said, “No, you guys do with it what you want when I’m not there anymore. Most important: I don’t want my music to be lost, and I want it to be conserved.” I think at that moment, he let go a bit of his ‘control.’ He liked being placed in the electronic wave, but there was so much more he did—classical but also funk. Also, here, Thierry has an important place. My father had made a list of music he wanted played at his funeral. On the list was the ‘Des Morts’ soundtrack, the violin version—a piece from Thierry’s documentary that he composed. That struck me hard: when he died, we played Des Morts, and three months later, there I was, standing in front of an audience, presenting his first soundtrack made in the seventies, now being put into a record. Beginning and ending with Thierry, like it was meant to be. The circle closed. As said, bittersweet…

How did your perspectives on ‘Vase de Noces’ and the soundtrack change as you learned more about the project after your father’s passing?

Tatiana: As said before, having talked to Thierry’s family and having my own stories, I like to think about the project as two very young men entering a world of millions of possibilities, not choosing the obvious way or being bothered by what others’ opinions would be. They just went for it, and at some point, got awarded for it. It’s a story I like to tell my kids these days: if it comes from your gut and one person believes in you, you can get far.

What aspects of the reissue process have been the most rewarding or meaningful for you and your family?

Tatiana: I think all of the above says it. But also, I’ve started the process to release some work that is not known at all. I think it is something a lot of composers will recognize: when you create, you dislike more than you like. Also, sometimes you just don’t want to be put in a specific corner or get heavy feedback. My father knew very well how he wanted to be seen. During our conversations, I sometimes asked why he wouldn’t release this or that track, and he would wave it away as “Ah, pfff, no, that’s nothing,” even if I explained to him that some songs would touch me. While he was dying, I got a look and a very short conversation from him that all of a sudden he understood there was so much more, and that we would treat this with great care. And he was ready for that. To me, this feels the most rewarding. He understood we wanted the world to know more about him, and we understood that he fulfilled the way he wanted his artist character to be seen during his life.

What do you hope listeners will take away from the ‘Vase de Noces’ soundtrack, especially those who may not be familiar with the film?

Tatiana: This is a difficult question. It depends on which generation is listening. Personally, I have no “hope” for anything. It’s also not a soundtrack that I would play from morning ‘till evening, hahaha.

But again, if you consider the time frame in which this was made, the experimental side, Belgium being such a small country, and those two boys going at it… I think it can be a nice piece for listeners to think: What would I have done? Knowing that everything was analogue in those days.

Or for today: How much do I take other people’s opinions into account? Do I push myself enough? Am I content?

Would love it if you could share some further insight about the other works he was involved with later on…

Tatiana: I think that would be a separate interview, to be honest. It’s actually pretty insane the number of projects he’s been involved in throughout his life.

I’m planning a social media platform about him in 2025. He left a museum of instruments, personal notes, film scripts, loads of music, and beautiful pictures. And I feel the urge to share it, as it’s a true trip from the seventies until today.

Regarding this legacy: I really do hope his work can inspire a wave of young artists pushing electronic music forward. He never backed down. He would never sell his soul, especially on personal projects. That often led to a lot of frustration: he couldn’t handle it when some other composer or artist went 100% commercial. He wanted to stay true to himself. Typical artist, of course, but I think that because of that, in some of his work, people all of a sudden can relate. Because there is honesty in it—sometimes filled with naivety, sometimes with full certainty. He loved to improvise. Not a lot of his work was put in notes or on paper. But it was all in his head. Always, until the end. To be a little more concrete about his work then and now: when you look at it from a distance, he didn’t “evolve” that much in his electronic music. I think he liked to be surrounded by his machines (some of which were still from the very beginning) and return to the atmospheres from back then. At the same time, he could embrace the evolution; especially the fact that digitalizing could literally spare him some room, as he kept all of his originals (BASF tapes, DATs, etc…) at home.

He loved mingling cultures and beats, putting artistic people who had nothing to do with each other in one room and seeing where this would lead. And often something would come out of it. He also produced other bands, singers, etc., acted once in a while, and wrote scripts. He would always brag that music was the best language to unite people, but also that creating was the best place to deal with your demons.

Klemen Breznikar

MYDY Bandcamp

Sub Rosa Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp